Abstract

This article discusses initiatives aimed at preventing and reducing ‘coercive practices’ in mental health and community settings worldwide, including in hospitals in high‐income countries, and in family homes and rural communities in low‐ and middle‐income countries. The article provides a scoping review of the current state of English‐language empirical research. It identifies several promising opportunities for improving responses that promote support based on individuals’ rights, will and preferences. It also points out several gaps in research and practice (including, importantly, a gap in reviews of non‐English‐language studies). Overall, many studies suggest that efforts to prevent and reduce coercion appear to be effective. However, no jurisdiction appears to have combined the full suite of laws, policies and practices which are available, and which taken together might further the goal of eliminating coercion.

Keywords: coercion, human rights, reducing coercion

Introduction

This article summarizes a scoping review that identified 121 English‐language studies in 40 + countries concerned with efforts to prevent and reduce ‘coercion’ in the mental health context. The findings compile current and recent prevention and reduction efforts with a view to supporting the further efforts of mental health practitioners, policymakers, service users, advocates and others. Findings are grouped into the categories of legislation, national policy, and hospital‐ and ‘community’‐based initiatives, each of which will be elaborated below. The term ‘persons with mental health conditions or psychosocial disabilities’, as adopted by the Human Rights Council in its 2017 Resolution on Mental Health and Human Rights 1 is used throughout.

Definitions and background

The Oxford English Dictionary defines coercion as ‘the action or practice of persuading someone to do something by using force or threats’ 2. Another common term, compulsion is defined slightly differently, as ‘the action or state of forcing or being forced to do something; constraint’ 3. In this article, the terms ‘coercion’ and ‘coercive practices’ are used to refer to both forceful persuasion and/or compulsion of a person – which emphasizes forceful action – due to an actual or perceived mental health condition 4.

Coercion in mental health settings is commonly associated with lawful powers of civil commitment, which may include detention in hospital, forced injection or ingestion of psychotropic drugs, involuntary electroconvulsive treatment, placement in seclusion, and mechanical, physical or chemical restraint.

However, coercion can also occur in nominally ‘voluntary’ service provision. The MacArthur Coercion Study, for example, which involved over 1500 adults admitted to hospitals in three United States jurisdictions over a 10‐year period, reported that a ‘significant minority of legally ‘voluntary’ patients experience coercion, and a significant minority of legally ‘involuntary’ patients believe that they freely chose to be hospitalized’ 5. Similar studies conducted elsewhere have shown comparable results 6.

Coercion also takes place outside hospitals including in individual and family homes, residential facilities, community services and elsewhere – for example, via ‘community treatment orders’ – particularly in high‐income countries. In some low‐ and middle‐income countries, coercion may also take the form of people being shackled, caged or detained in homes, communal areas, sheds, cages, or ‘prayer camps’ and other sites in which liberty is deprived and other rights violations occur 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

We acknowledge calls for a more precise taxonomy of coercion and compulsion along a spectrum from persuasion through ‘interpersonal leverage’, inducements (or offers), and threats, to the use of formal, legal compulsion or informal deprivations of liberty, but seek in this review to take a generalized view of empirical efforts to reduce coercive practices 12.

Several factors have driven efforts to remove coercion from mental health settings, including people who have been subjected to forced interventions drawing attention to the harm of coercive practice 13, 14, 15; professional groups who have positioned ‘compulsion… as a system failure’ 16; and developments in international human rights law, particularly the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 17, 18. Several governments have pivoted away from coercive practices 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and local‐level initiatives aimed at reducing and eliminating coercive practices have occurred in hospital‐ or service‐based programmes, and in community initiatives 24, 25, 26, 27, 28. In sum, efforts are underway at the international, regional, national and local levels to reduce, prevent and end coercive practices and, instead, provide the highest quality support that serves, on a voluntary basis, ‘to protect, promote and respect all human rights and fundamental freedoms’ 1.

Despite this interest in preventing coercion, it appears that there has not yet been a systematic review of efforts to prevent and reduce coercive practices in the mental health context, broadly conceived. Hence, the authors undertook a scoping review to this end.

Although a scoping review does not have the focus of a systematic review that covers defined study types, scoping reviews use strict, transparent methods for surveying the literature. Importantly for this study, scoping reviews are particularly useful for surveying a large field that has not been comprehensively reviewed, and for which concepts and themes require clarification 29. The scoping review encompassed empirical studies on preventing and reducing coercive practices in mental health settings.

Methodology

Aim

The aim of this study was to identify all studies within a selective sampling frame 30, that answered the following research questions:

What practices, policies and laws help to reduce and prevent coercive practices in mental health settings?

What alternative strategies, laws, policies and/or practices exist which could be positioned as ‘alternatives’ to or replacements for coercive practices?

The review findings may be used to make recommendations for future research and policymaking.

Design

The study comprised a scoping review which involved a broadly defined research question and the development of inclusion/exclusion criteria post hoc at study selection stage. Study selection included all empirical study types, and the overall aim was to ‘chart’ data according to key issues, themes and gaps 31. Materials were analysed using thematic content analysis, as well as doctrinal legal analysis 32. Doctrinal legal analysis involves identifying a problem of justice (in this instance the restriction on certain rights) and canvassing alternatives 33.

Search methods

A rapid review method or streamlined literature review was used. Numerous search strings in multiple combinations, using the following terms, were used in keyword fields, or abstract and title fields (where available in each database):

‘mental (health or ill* or disability or impair*)’; ‘coerc* or forced or compulsory or involuntary*’; ‘psychiatr*’; ‘disab*’; ‘disability law’; ‘alternative*’; ‘health*’; ‘health services’; ‘right to health’; ‘alternative*’; ‘advoca*’: ‘user’; ‘survivor’; ‘crisis respite’; ‘trauma‐informed’; ‘recovery’, etc.

The following research databases were used: PUBMED (including MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books);INFORMIT (encompassing AGIS, Health Collection, Health and Society Database); EBSCO (encompassing Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Complete, Index to Legal Periodicals); PROQUEST (which includes Health and Medical Collection and Psychology Database); Science Direct Journals; SSRN; Google Scholar; and LegalTrac.

A limit was placed on the date range for the search, from 1990 and 31 September 2018. A language filter was applied to focus on English‐language results. (Material primarily concerning ‘deinstitutionalisation’ was also excluded. Although deinstitutionalization overlaps with ‘reducing and ending coercion’ in the strict sense, it is a relatively discrete public policy phenomenon, which has been subject to considerable research) 34, 35. The criteria adopted were taken for pragmatic reasons to reduce the scope and complexity of the search.

Role of funding source

We note that the detailed literature review, which we summarize here, was funded by the United Nations Office at Geneva, to inform the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, Ms. Catalina Devandas Aguilar. The information and views contained in this research are not intended as a statement of the Special Rapporteur for Disability, and do not necessarily, or at all, reflect the views held by the Special Rapporteur. The United Nations Office assisted with the research design, but not in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data. The authors of this paper had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Charting the data

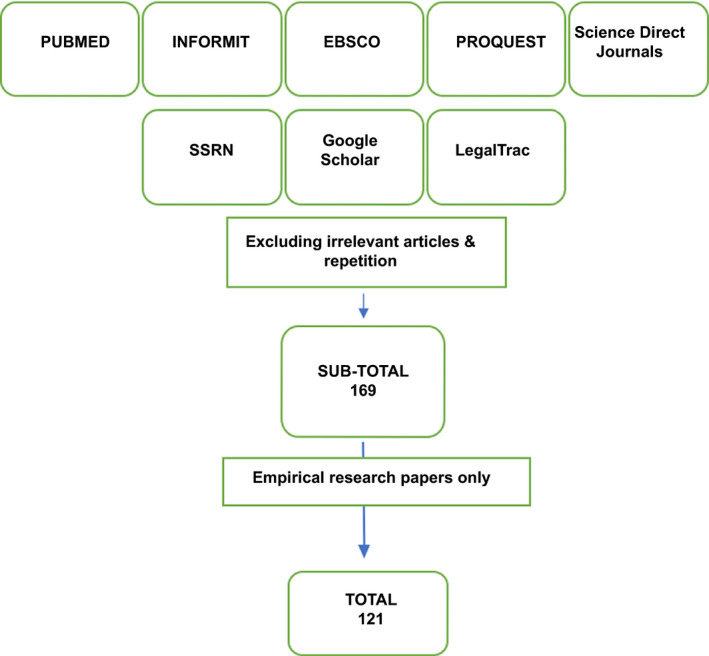

After an extensive search, 500 + relevant peer‐reviewed research studies were identified for review. From these, non‐research articles (theoretical papers, reviews, overviews and commentaries), articles which were not available in English, duplicates and articles not available in full text (and where a detailed abstract was not available) were excluded. This resulted in a total of 121 empirical research papers included in the review. Figure 1 sets out the process of exclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing exclusion process. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Methods used in studies

Most papers used quantitative methodology, numbering a total of 73.Most analysed service data, such as reports of seclusion or restraint incidents, and rates of involuntary detention. Overall, sample sizes tended to be small and used convenience sampling. A small number of national surveys provided valuable generalizable data.

There were 26 qualitative studies. They typically consisted of interviews and provided an insight into the subjective experiences of participants, and detailed understandings of enablers and barriers that reduce or remove coercive practices in a variety of settings. Sample sizes in qualitative studies were often small and non‐generalizable, with limitations in study design, length of trial periods and settings.

Research by region

Unsurprisingly, given the English‐language bias in the study, most of the reviewed research was conducted in North America and Western Europe, particularly United States, the United Kingdom (particularly England), the Netherlands and Northern Europe (as indicated in Table 1). Representation in the table below does not necessarily convey the number of studies undertaken in each region; for example, one study encompassed all South American countries 36, and another, single study concerned seven African countries 37.

Table 1.

Regions in which studies found in the literature review were conducted

| Region | N | Specific countries |

|---|---|---|

| Asia | 6 | India (2), Indonesia (3), China (1) |

| Eastern Europe | 4 | Bulgaria (1), Czech Republic (1), Lithuania (1), Poland (1), |

| Latin America | 15 | Argentina (2), Mexico (1), Chile (2); Bolivia (1), Brazil (1), Colombia (1), Ecuador (1), Guyana (1), Paraguay (1), Peru (1), Suriname (1), Uruguay (1), Venezuela (1) |

| Middle East | 0 | ‐ |

| North America | 28 | United States (25), Canada (3) |

| Northern Africa | 4 | Kenya (1), Uganda (1), Ethiopia (1), Ghana (1) |

| Oceania | 7 | Australia (7) |

| Southern Africa | 4 | Rwanda (1), Tanzania (1), South Africa (1), Zambia (1) |

| Southern Europe | 7 | Croatia (1), Italy (3), Greece (1), Spain (2) |

| Western Europe | 81 | Denmark (10), Finland (5), Germany (7), Iceland (1), Netherlands (15), Norway (9), Sweden (8), Switzerland (6), England (20) |

Limitations

Given the broad inclusion criteria, the studies were heterogenous and complex. Efforts to address coercion were highly varied and context‐specific. In most cases, multiple contested ideas and values were at play and variable confounding factors pose several challenges for researchers. Variations in terminology, aims, scale, sampling and research quality, made generalizability difficult. Consider the challenge of comparing a study on the impact of the temporary invalidation of civil commitment powers in Germany, with a study on advance directive measures within mental health legislation elsewhere; or a community‐based initiative to reduce ‘shackling’ of individuals in Indonesia compared to a UK‐based initiative to eliminate physical and mechanical restraint in state‐run crisis centres. Another one of the disadvantages of using a rapid review method is that it is difficult for researchers to reproduce the results when using numerous search stings in multiple combinations. Notwithstanding these caveats, the empirical studies in the range of efforts offer valuable lessons.

Summarizing the findings

The studies typically focused on adults with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, both men and women (with several studies focusing on gender). A small number of studies concerned specific groups, such as prisoners or forensic mental health patients 27, 38, children and adolescents 39, older adults 40, 41, and ethnic minorities or migrant groups 42, and some focused on the views of professionals, typically in clinical settings.

While research design varied, several study types emerged. These could be distinguished into the following categories:

-

i)

Studies concerning practices (whether in law, policy or practice) that were explicitly designed to reduce or remove coercion (42 studies) 8, 20, 43, 44;

-

ii)

Studies to evaluate the effectiveness of practices that could be broadly considered ‘alternatives’ to acute hospital treatment, including crisis respite houses, intensive home‐based support and supported decision‐making, in which coercion reduction, prevention or elimination and greater individual autonomy was one (often tacit) underlying aim (29 studies) 26, 45, 46;

-

iii)

Studies to understand views on coercion among those who have been subjected to coercion, as well as people employed in services, and family members 10, 47, 48 (again, with a secondary aim of using findings to reduce coercion or, somewhat more ambiguously in one case, to ‘utiliz[e] interventions to enhance treatment adherence in an informed and ethical way’49) (16 studies);

-

iv)

Studies to identify factors that seemingly contributed to higher or lower rates of coercion, with the aim of using findings to reduce or eliminate coercion (for example, comparing hospital wards that had high rates of mechanical restraint to those with low or no rates 50, or seeking to understand whether ethnic minorities experienced coercion at higher rates and, if so, why 17 studies) [39, 51, 52, 53].

Less common study types sought the following:

-

i)

To assess the impact of rates of one type of coercion (for example, reducing physical restraint) on rates of other types of coercion (such as chemical restraint) or on rates of ‘conflict’ (4 studies) 54, 55, 56, 57;

-

ii)

To identify efforts that indirectly resulted in reductions in coercion (for example, testing whether unlocked wards or increased service funding reduced coercion) (3 studies) 21, 58, 59;

-

iii)

To investigate the impact of service user organizations and their individual and systemic advocacy to prevent coercive practices and develop ‘alternative rights‐based approaches’ (2 studies) 9, 37;

-

iv)

To examine legal and practice issues related to the exercise of ‘powers’ of coercion, for example in housing 60 or social work 61, again with the aim of reduction or elimination (6 studies)62, 63, 64;

-

v)

To examine problems defining and recording coercive measures, with the aim of improving data collection to inform reduction or elimination efforts (2 studies) 65, 66.

Many of the studies could have been placed in two or more categories. For clarity, however, each study was placed into one of the above categories based on its over‐arching character. This categorization provides one way of understanding the review materials and offers a useful conceptual heuristic.

This article focuses on practices explicitly aimed at preventing or reducing coercion, and other categories such as ‘alternatives’ and studies that identified factors that contribute to reduction and elimination efforts. (A full list of materials that appeared in the literature review, including a summary of each study, and a broader scoping review of ‘grey literature’ has been published elsewhere) 67.

Thematic summary of the literature

In general terms, the studies that focused on explicit efforts to prevent or reduce coercion reported ‘positive’ results in almost every instance; that is, coercion was effectively prevented, reduced and even completely discontinued. Prominent practices included ‘Six Core Strategies for Restraint Minimisation’, ‘No Force First’ initiatives, advance planning to avoid or better respond to crises, ‘open door’ policies in hospitals and other facilities, the use of ‘crisis respite houses’, family‐based interventions, measures to release people from communal settings and family homes in which they were deprived of liberty, the use of non‐legal advocacy, and so on. There were very few neutral or adverse outcomes caused by such efforts (four studies reported neutral impact, and two reported adverse findings, all of which are discussed later in this article). Overwhelmingly, governments, service providers or community advocates have been effective – to varying degrees – when taking steps to prevent or reduce coercive practices. Hence, the evidence base is compelling, with the majority of studies detailing effective means under existing conditions to prevent or reduce coercive practices.

It should be noted that the literature may be influenced by ‘publication bias’ 68. Publication bias refers to the phenomenon whereby negative results as a general rule are less likely to be submitted for publication in journals and even if submitted, are less likely to be published. Even though, as noted, six studies did report neutral or adverse outcomes, the potential for publication bias cannot be discounted.

In terms of categorizing the materials into themes, the following categories emerged: legal change, government policy change and hospital‐ and ‘community’‐based changes to practice.

Legal change

Eight studies examined the impact of legal change on rates of coercion in mental health settings (four studies concerned a single law reform initiative in Germany) 21, 22, 23, 60, 69, 70, 71, 72. In one instance, in Germany, the legal change was a response to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities(‘CRPD’), while the other three examples, in Italy, Switzerland and the United States, concerned measures introduced prior to the CRPD coming into force in 2008.

In Germany, in 2011 and 2012, several landmark decisions by the German Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) and Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) narrowed the grounds for involuntary psychiatric interventions to ‘life‐threatening emergencies’ only 73. In one German state, according to Erich Flammer and Tilman Steinert, ‘involuntary medication of psychiatric inpatients was illegal during eight months from July 2012 until February 2013’ 73. According to Martin Zinkler, the legal provisions, which were based on Germany’s obligations under the CRPD, led to ‘examples where clinicians put an even greater emphasis on consensual treatment and did not return to coercive treatment’ 22. Zinkler observed the following in a case study concerning one mental health service, Heidenheim, that services a population of 130 000: the frequency of violent behaviour and the frequency of other forms of coercion did not increase in Heidenheim once coercive use of antipsychotic medication was abandoned. During this period however, a shift in the therapeutic culture led to a reduction in the use of antipsychotic medication of more than 40% 22.

This case study, according to Zinkler, suggests that the ‘use of coercive medication could be made obsolete’ 22. Flammer and Steinert, using routine data on 2644 ‘treatment cases’, point to some evidence that the legal reform led to a reduction in the use of involuntary medication even after the court changes were wound back 72. In contrast to Zinkler, they reported that the ‘number of mechanical coercive measures increased by over 40% in the cross‐sectional analysis [and] [i]n the longitudinal analysis… the increase of both aggressive incidents and coercive measures was over 100%’ 72.

Of the pre‐CRPD legislative changes to be analysed in terms of their impact on reducing coercive interventions, Italy’s well‐known ‘Law 180’ was the most far‐reaching insofar as the law mandated the creation and public funding of community‐based therapeutic alternatives to institutional settings and affordable living arrangements. Mezzina undertook a general review of the available literature on ‘Law 180’ and presented some evidence of the law’s impact over 40 years, stating that ‘[m]echanical restraints have been abolished in health and social care, including nursing homes and general hospitals’ 23. He points out that after the law was enacted in 1978, involuntary treatments ‘dropped dramatically’ and Italy ‘sustained the lowest ratio in Europe (17/100 000 in 2015) and the shortest duration (10 days)’ 23, although it is not clear to which data he is referring when making this claim. In the city of Trieste and also the Friuli‐Venezia region, according to Mezzina, ‘[i]nvoluntary treatments show the lowest rate in Italy, and about 40% of them are managed in [Community Mental Health Centres] with open doors’ 23.

Three other studies concerned more modest legal reform. A Californian study examined the impact of a USD$3·2 billion tax revenue investment generated by the state’s Mental Health Services Act2004 (MHSA) on quarterly rates of ‘72‐hour holds’ (N = 593 751) and ‘14‐day psychiatric hospitalizations’ (N = 202 554) 60. The researchers attributed 3073 fewer involuntary 14‐day treatments – approximately 10% below previous levels – to the disbursement of MHSA funds 60. Ariel Eytan and colleagues 21 examined a 2006 Swiss law that restricted the authority to order compulsory admission only to certified psychiatrists. They point to data from a single hospital that showed a reduction in compulsory admissions from 69% in 2005 to 48% in 2007 after the law was introduced, and the rate remained below 50% in the years to 2013 21. In Finland, Alice Keski‐Valkama and colleagues undertook a structured postal survey of Finnish psychiatric hospitals to evaluate the impact of law reform aimed at reducing the use of seclusion and restraint over a 15‐year span 69. They reported that the total number of patients secluded and restrained declined as did the number of all inpatients during the study weeks, but the risk of being secluded or restrained for individuals who were in hospital remained the same over time when compared to the first study year.

National policies

Several studies undertook analyses of national practices and policies 19, 20, 74. For example, Eric Noorthoorn and colleagues studied the result of more than 100 seclusion reduction projects in 55 hospitals, following €35 million in funding from the Dutch government 20. The average yearly nationwide reduction of patients who were secluded recorded by this study was about 9% 29. Another study, compared disparities between mechanical restraint use from all psychiatric hospital units in Denmark 75 and Norway 76 and found that three mechanical restraint preventive factors were significantly associated with low rates of mechanical restraint use: ‘mandatory review’ (exp[B] = 0.36, P < 0.01), ‘patient involvement’ (exp[B] = 0.42, P < 0.01), and ‘no crowding’ (exp[B] = 0.54, P < 0.01) 77.

In China, Lili Guan and colleagues studied the result of a national policy, referred to as the ‘686 Program’, which was designed to reduce and eliminate incidents of community‐based ‘shackling’ of persons with psychosocial disabilities by extending ‘community‐based mental health services’ to individuals and their families. The authors reported a 92% success rate for those previously detained, as recorded in 2012 and proposed that the policy sets a useful precedent for low‐ and middle‐income countries, which face family‐ or communal‐based shackling 43.

Changes in practice

Changes in practice can be broadly distinguished between hospital and ‘community’‐based initiatives. Each will be discussed in turn. ‘Practice’ is used here to refer to service provision but could also include less formal initiatives, such as informal service user groups, community organizing, and so on.

Hospital‐based initiatives

The literature on hospital‐based practices identifies multiple initiatives for reducing coercion 24, 65, 78, 79, 80. For the sake of brevity, this section focuses on the following practices: Six Core Strategies to Reduce the Use of Seclusion and Restraint, Safewards and open door policies.

Six Core Strategies to Reduce the Use of Seclusion and Restraint, a United States initiative developed in 2005 81, focuses on the strategic use of data, leadership towards organizational change, workforce development, service user roles in inpatient settings and debriefing techniques 82. Several empirical studies reported a significant decrease in the use of seclusion and restraint following implementation 27, 28, 80. Sanaz Riahi and colleagues reported a 19.7% decrease in incidents of seclusion and restraint from 2011/12 to 2013/14 in a tertiary level mental health care facility in Ontario, Canada, with a 38.9% decrease in the average length of a mechanical restraint or seclusion incident over the 36‐month evaluation period 28.

‘Safewards’ is another hospital‐based initiative aimed at reducing conflict, restraint and seclusion on hospital wards responding to mental health crises 82. Safewards focuses on interventions designed to help staff manage ‘potential flashpoints’, emphasizing service culture, including staff interactions with patients, family/friends and the physical characteristics of wards. Len Bowers and colleagues’ cluster randomized controlled trial of the initiative across 31 wards in England reported an estimated 15% decrease in conflict and 24% decrease in ‘containment’ 80. Notably, however, Feras Ali Mustafa has criticized the methodology used for this evaluation 83. In Australia, an assessment of a Safewards trial in 13 different wards found seclusion rates were reduced by 36% in the trial wards by the 12‐month follow‐up period, and the authors concluded that ‘Safewards is appropriate for practice change in… inpatient mental health services more broadly than adult acute wards, and is effective in reducing the use of seclusion’ 84.

Several other studies examined efforts to reduce seclusion and restraint. Maureen Lewis and colleagues, for example, examined a 900‐bed tertiary care academic medical centre located in an ‘urban, socioeconomically distressed area’ 85. They reported on a group of direct care psychiatric nurses who created a performance improvement programme that resulted in a decrease in the use of seclusion and restraint. No additional funds were required to develop this programme with early results showing a 75% reduction in the use of seclusion and restraint with no increase in patient or staff injuries since its implementation 56.

Five studies examined locked/unlocked door or ‘open door’ policies in mental health wards (and others referred to unlocked facilities in ‘community’‐based sites, such as respite houses, which will be discussed below). Christian Huber and colleagues argued that there is insufficient evidence that treatment on locked wards can effectively prevent absconding, suicide attempts, and death by suicide 59. Andres Schneeberger and colleagues, drawing on two large‐scale studies based on data for 349 574 admissions to 21 German psychiatric inpatient hospitals from 1998, to 2012, indicated that hospitals with an ‘open door policy’ did not have increased numbers of suicide, suicide attempts, and absconding with return, and without return 56, 59. Conversely, they reported that treatment on open wards correlated with a decreased probability of suicide attempts, absconding with return, and absconding without return, but not completed suicide 59. They further found that ‘[r]estraint or seclusion during treatment was less likely in hospitals with an open door policy’, as was aggressive behavior 86. A critic of the study raised the concern that ‘open door policy’ was classified arbitrarily by the researchers 75, though the authors refute the claim 86.

Several other studies support the view that locked doors might not be able to prevent suicide and absconding and have several downsides, from both a pragmatic and rights‐based perspective. Bowers and colleagues 87 conducted a survey in England, receiving responses from a total of 1227 patients, staff and visitors on the practice of door locking in acute psychiatry wards. The researchers did not consider the impact of open door policies on other forms of seclusion and restraint. Instead, they focused on service user, visitor and staff perceptions. They found that the service users held more negative views about door locking than staff, including reporting feeling anger, irritation and depression as a consequence of locked doors, while staff tended to associate locked wards more positively, as did the (relatively few) informal visitors who responded to the survey 50.

In addition to these three major focus areas, studies in this category also concerned the following: changing environmental factors within health settings which seem to increase the likelihood of coercion under current conditions 83, 88 the number/ratio of service users to staff and staff characteristics 50, 78, the impact of reporting registries and requirements to report on coercive practices 57, and the use of de‐escalation techniques 79, 89. Bowers and colleagues undertook an analysis of wards with the counterintuitive combination of ‘low containment and high conflict’ or ‘high containment and low conflict’, and sought to understand the contributing factors 81. They reported that high‐conflict, low‐containment wards had higher rates of male staff and lower‐quality environments than other wards, while low‐conflict, high‐containment wards had higher numbers of beds. High‐conflict, high‐containment wards utilized more temporary staff as well as more unqualified staff. The researchers argued that wards can make positive changes to achieve a low‐containment, nonpunitive culture, even when rates of patient conflict are high. Some studies considered demographic effects on rates of coercion. Wim Janssen and colleagues, for example, identified differing seclusion figures between wards in Dutch psychiatric hospitals and sought to test the view of nurses and ward managers that the differences ‘may predominately be explained by differences in patient characteristics, as these are expected to have a large impact on these seclusion rates’ 90. They investigated differences in patient and background characteristics of 718 secluded patients over 5097 admissions on 29 different admission wards over seven Dutch psychiatric hospitals. The researchers found that ‘both patient and ward characteristics’ could partially explain differences in seclusion rates but that ‘the largest deal of the difference between wards in seclusion rates could not be explained by characteristics measured in this study’ and instead concluded that ‘ward policy and adequate staffing may, in particular on smaller wards, be key issues in reduction of seclusion’ 91. Tonje Husum and colleagues 91 had similar findings, concluding that ‘interventions to reduce the use of seclusion, restraint and involuntary medication should take into account organizational and environmental factors’.

For hospital‐based practitioners, this overview suggests that the studies on Safewards, the Six Core Strategies and Open Door Policies indicate a high degree of evidence for reducing the use of coercive measures in clinical practice.

‘Community’‐based strategies

The review identified a growing body of research into efforts outside hospitals and other clinical mental health settings, which aim to prevent a person being subject to coercive practices. This category includes the use of advance‐care planning in community‐based services, or the use of neighbourhood crisis services, crisis resolution, respite houses and home‐based support in order to avoid disputes concerning hospitalization and unwanted treatment.

Crisis homes offer a smaller scale residential alternative for people in crisis, sometimes designed for specific groups, including women, and minority ethnic groups. In the United States, Thomas Greenfield and colleagues 92 compared the effectiveness of an unlocked, mental health consumer‐managed, crisis residential programme to a locked, inpatient psychiatric facility (LIPF) for adults with severe mental health conditions. This randomized trial, involved 393 adults who were subject to involuntary treatment orders. Participants in the crisis residential programme reportedly experienced significantly greater improvement based on ‘interviewer‐rated and self‐reported psychopathology’ than did participants in the LIPF condition 76. Reported service satisfaction was ‘dramatically higher’ in the crisis residential programme condition, leading the researchers to conclude that ‘[crisis residential programme]‐style facilities are a viable alternative to psychiatric hospitalization for many individuals facing civil commitment’ 76.

Some crisis houses are managed and run by service users, former service users, and other persons with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, and typically have a strong recovery and self‐help ethos. Bevan Croft and Nilüfer Isvan 76 compared the experiences of 139 users of peer respite and 139 non‐users of respite services. Their findings suggest that ‘by reducing the need for inpatient and emergency services for some individuals, peer respites may increase meaningful choices for recovery and decrease the behavioural health system’s reliance on costly, coercive, and less person‐centred modes of service delivery’ 76.

The results of the studies examined suggest the conceptual binary of ‘community’ versus ‘hospital‐based’ care may be misleading in some respects. In high‐income Western countries, these two categories have traditionally denoted services for either acute (hospital) or non‐urgent (community) responses. ‘Community’ supports might include the use of General Practitioners, supported housing, residential facilities, ‘psychosocial rehabilitation’, and so on. Yet, the review materials suggest that an alternative, and perhaps more useful distinction, might be between ‘crisis resolution’ and ‘general support’. ‘Crisis resolution’ – in most places – includes hospital‐based support, but could also include crisis respite houses, intensive home‐based support, and step‐up/step‐down residential programmes for periods of acute crisis. ‘General support’ could include the range of non‐emergency community‐based services that currently exist to assist people to live full lives, including to prevent crises; for example, by using independent advocacy, housing support, employment support and personal assistance.

Several themes emerged in which practices cut across hospital and ‘community’‐based settings. These included: non‐legislative approaches to advance planning 93, 94, 95; the impact of greater satisfaction with prior treatment on the risk of being coerced in the future 96; and culturally appropriate pathways to supporting people in distress 52, 97.

Ten studies explicitly engaged with advance planning framed as a potential means of planning for crises and avoiding disputes concerning hospitalization and treatment 94, 95, 96. There is undoubtedly a much larger literature concerning advance planning but studies that assessed its impact on rates of coercion were highlighted. The findings were somewhat mixed, but generally suggested a positive impact under current legal frameworks. Alexia Papageorgiou and colleagues in their study found users’ advance instruction directives had little observable impact on compulsory readmission rates at 12 months 50. In contrast, however, Mark de Jong and colleagues conducted a systematic literature review on advance statements, including a meta‐analyses of all randomized control trials (RCTs), which they argue ‘showed a statistically significant and clinically relevant 23% reduction in compulsory admissions of adults with mental health conditions, whereas the meta‐analyses of the RCTs on community treatment orders, compliance enhancement, and integrated treatment showed no evidence of such a reduction’ 98.

Neutral or adverse outcomes

Only four studies reported on neutral outcomes from reduction/prevention/elimination initiatives. Researchers in one study found that ‘joint crisis plans’ did not reduce rates of compulsory admission or treatment in England and Wales, as a previous study had found 99. This was a similar finding to that of Papageorgiou and colleagues, as noted in the previous paragraph 99. Sonia Johnson and colleagues 46 found that a crisis resolution team based in the community did not have a significant impact upon rates of compulsory admission, although the team’s intervention did reduce the likelihood of hospitalization in the 8 weeks following. In a Danish study using all available national data where ‘patient controlled admission’ is available, the researchers found that implementing patient‐controlled admission did not reduce coercion, service use or self‐harm behaviour when compared with treatment as usual, but it did identify beneficial effects of patient‐controlled admission in the before and after patient‐controlled admission comparisons, which showed some reduction in coercion (P = 0.0001) and in‐patient bed days (P = 0.0003) 44.

Only two studies reported what might be described as adverse outcomes as a result of efforts to explicitly prevent coercive practices. The invalidation of civil commitment powers in Germany except in ‘life‐saving emergencies’, according to Flammer and Steinert, reportedly led to an increase in the use of mechanical restraint and ‘violent incidents’ in some parts of Germany 73 (though Zinkler’s study found no such effects in one German town, as discussed) 22. In the Netherlands, Fleur Vruwink reported that among the Dutch hospitals that received a government grant programme designed to reduce seclusion and involuntary medication, seclusion rates dropped (though did not fall to the 10% desired by policy planners), while the number of involuntary medications did not change; instead, after correction for the number of involuntary hospitalizations, it increased 19.

Gaps

There are several gaps and limitations in the literature identified by the researchers, including:

The need for a comprehensive review of non‐English materials

Relevant efforts are underway in countries with national languages other than English, which should be captured in an exhaustive global review.

Research explicitly premised on reducing and preventing coercion

Only 42 of the studies concerned initiatives explicitly aimed at preventing or reducing coercion in mental health settings. This is striking, particularly given the broad inclusion criteria in this study. For the remaining 79 studies, preventing or reducing coercion was an indirect outcome of each initiative. A research field is required that is unambiguously aimed at identifying effective measures to prevent, reduce and eliminate coercive interventions.

Active involvement of those who have been subjected to coercive interventions

Formal research typically did not involve people who have used mental health services or experienced involuntary interventions, as either active research participants – for example as interviewees, survey recipients, and so on – or as lead or co‐researchers. There were several notable exceptions to this trend 49, 53, 100

A lack of qualitative research

Qualitative research, and particularly phenomenological research, remains under‐utilized given most current strategies for preventing, reducing or ending coercive practices involve complex social and policy interventions, which generate variable confounding factors.

Research on organizational cultural change

Organizational cultural change was an important component of efforts recorded in the study but were rarely a primary consideration. Although some literature assesses the organizational social context 101, 102 there is relatively little research on effective ways to change service culture, or management culture; for example, through social psychological theories of group processes and intergroup behaviour.

Increased research of existing ‘promising practices’

Rates of coercion within and between countries vary greatly, and successful initiatives may remain unexamined or under‐examined in research and evaluation.

A focus on specific groups

Very few initiatives aimed at reducing coercion against particular groups, and particularly those who may be subject to greater levels of coercion, such as children, older persons, people from specific cultural groups, and people with intellectual and cognitive disabilities.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the limitations in the research, efforts to prevent or reduce coercion appear effective in many studies. A broad suite of practices, policies and interventions exist, with varying degrees of evidence to support them, which can be either implemented or tested at local, national and regional levels. A broad policy ‘charter’ or ‘framework’ could collate these findings, outlining the diverse package of options that have been introduced and tested elsewhere, or which warrant further investigation.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

All three authors co‐designed the study. Dr Gooding gathered the literature and charted the data. All three authors analysed the findings and co‐wrote the summary.

Gooding P, McSherry B, Roper C. Preventing and reducing ‘coercion’ in mental health services: an international scoping review of English‐language studies.

References

- 1. United Nations Human Rights Council . Resolution on mental health and human rights, UN Doc A/HRC/36/L.25 (2017) 4.

- 2. Oxford Dictionaries .Definition of coercion in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press;2020. [cited 2019 Apr 7]. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/coercion [Accessed 8 June 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oxford Dictionaries .Definition of compulsion in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019. [cited 2019 Apr 7]. Available from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/compulsion. Accessed 8 June 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Szmukler G. Compulsion and “coercion” in mental health care. World Psychiatry 2015;14:259–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Monahan J, Lidz C, Hoge SK et al. coercion in the provision of mental health services: the macarthur studies In: Morrissey JP, Monohan J, eds. Research in community and mental health, Vol. 10 – Coercion in mental health services: international perspectives. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 1999:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poulsen HD. The prevalence of extralegal deprivation of liberty in a psychiatric hospital population. Int J Law Psychiatry 2002;25:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fennell P. Institutionalising the community In: McSherry B, Weller P, eds. Rethinking rights‐based mental health laws. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suryani LK, Lesmana CBJ, Tiliopoulos N. Treating the untreated: applying a community‐based, culturally sensitive psychiatric intervention to confined and physically restrained mentally ill individuals in Bali, Indonesia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;261:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Asher L, Fekadu A, Teferra S, De Silva M, Pathare S, Hanlon C. ‘I cry every day and night, I have my son tied in chains’: physical restraint of people with schizophrenia in community settings in Ethiopia. Global Health 2017;13:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minas H, Diatri H. Pasung: physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community. Int J Ment Health Sys 2008;2:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Puteh I, Marthoenis M, Minas H. Aceh Free Pasung: releasing the mentally ill from physical restraint. Int J Ment Health Sys. 2011;5:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szmukler G. Treatment pressures, coercion and compulsion in mental health care. J Ment Health 2008;17:229–231. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spandler H, Anderson J, Sapey B, eds. Madness, distress and the politics of disablement. Bristol: Policy Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fabris E. Tranquil prisons: mad peoples experiences of chemical incarceration under community treatment orders. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flynn E, Arstein‐Kerslake A, De Bhalis C, Serra ML, eds. Global perspectives on legal capacity reform: our voices. Our stories. London: Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhugra D, Tasman A, Pathare S et al. The WPA‐lancet psychiatry commission on the future of psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:775–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities , opened for signature 30 March 2007, Doc.A/61/611 (entered into force 3 May 2008) (“CRPD”). Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html. [Accessed 8 June 2019].

- 18. Martin W, Gurbai S. Surveying the Geneva impasse: coercive care and human rights. Int J Law Psychiatry 2019;64:117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vruwink FJ, Mulder CL, Noorthoorn EO, Uitenbroek D, Nijman HLI. The effects of a nationwide program to reduce seclusion in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noorthoorn EO, Voskes Y, Janssen WA et al. Seclusion reduction in Dutch mental health care: did hospitals meet goals? Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eytan A, Chatton A, Safran E, Khazaal Y. Impact of psychiatrists’ qualifications on the rate of compulsory admissions. Psychiatr Q 2013;84:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zinkler M. Germany without coercive treatment in psychiatry – a 15 month real world experience. Laws 2016;5:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mezzina R. Forty years of the law 180: the aspirations of a great reform its successes and continuing need. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2018;27:336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borckardt JJ, Madan A, Grubaugh AL et al. Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foxlewin B. What is happening at the seclusion review that makes a difference?: A consumer led research study. Canberra: ACT Mental Health Consumer Network, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sledge WH, Tebes J, Rakfeldt J, Davidson L, Lyons L, Druss B. Day hospital/crisis respite care versus inpatient care, Part I: Clinical outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1065–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maguire T, Young R, Martin T. Seclusion reduction in a forensic mental health setting. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2012;19;97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Riahi S, Dawe IC, Stuckey MI, Klassen PE. Implementation of the six core strategies for restraint minimization in a specialized mental health organization. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016;54:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooper H. Research Synthesis and meta‐analysis: a step‐by‐step approach, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hutchinson T, Duncan N. Defining and describing what we do: doctrinal legal research. Deakin Law Rev 2012;17:83–119. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minow M. Archetypal legal education – a field guide. J Leg Educ 2013;63:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shorter E. A history of psychiatry: from the era of the Asylum to the age of Prozac. London: Wiley and Sons, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scull A. Decarceration: community treatment and the deviant: a radical view. Cambridge: Polity, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larrobla C, Botega NJ. Restructuring mental health: a South American survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kleintjes S, Lund C, Swartz L. Organising for self‐advocacy in mental health: experiences from seven African countries. Afr J Psychiatry 2013;16:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ollson H, Schön UK. Reducing violence in forensic care ‐ how does it resemble the domains of a recovery‐oriented care. J Ment Health 2016;25:506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin A, Krieg H, Esposito F, Stubbe D, Cardona L. Reduction of restraint and seclusion through collaborative problem solving: a five‐year prospective inpatient study. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:1406–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mann‐Poll PS, Smit A, Noorthoorn EO, Janssen WA, Koekkoek B, Hutschemaekers GJM. Long‐term impact of a tailored seclusion reduction program: evidence for change? Psychiatr Q 2018;89:733–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gjerberg G, Hem MH, Førde R, Pedersen R. How to avoid and prevent coercion in nursing homes: a qualitative study. Nurs Ethics 2013;20:632–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norredam M, Garcia‐Lopez A, Keiding N, Krasnik A. Excess use of coercive measures in psychiatry among migrants compared with native danes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;121:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guan L, Liu J, Wu XM et al. Unlocking patients with mental disorders who were in restraints at home: a national follow‐up study of China’s new public mental health initiatives. PLoS ONE 2015;10:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomsen CT, Benros ME, Maltesen T et al. Patient‐controlled hospital admission for patients with severe mental disorders: a nationwide prospective multicentre study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018;137:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sledge WH, Tebes J, Wolff N, Helminiak TW. Day hospital/crisis respite care versus inpatient care, Part II: Service utilization and costs. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1074–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson S, Nolan F, Piling S et al. Randomised controlled trial of acute mental health care by a crisis resolution team: the North Islington crisis study. BMJ;331:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Olsson H, Schön UK. Reducing violence in forensic care ‐ how does it resemble the domains of a recovery‐oriented care. J Ment Health 2016;25:506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kokanović R, Brophy L, McSherry B, Flore J, Moeller‐Saxone K, Herrman H. Supported decision‐making from the perspectives of mental health service users, family members supporting them and mental health practitioners. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2018;52:826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gilburt H, Slade M, Rose D, Lloyd‐Evans B, Johnson S, Osborn DP. Service users’ experiences of residential alternatives to standard acute wards: qualitative study of similarities and differences. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2010;53:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bak J, Zoffman V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Siersma VD, Brandt‐Christensen M. Comparing the effect of non‐medical mechanical restraint preventive factors between psychiatric units in Denmark and Norway. Nord J Psychiatry 2015;69:433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO et al. Pennsylvania state hospital system’s seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv 2005;56:1115–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lawlor C, Johnson S, Cole L, Howard LM. ethnic variations in pathways to acute care and compulsory detention for women experiencing a mental health crisis. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2012;58:3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barrett B, Waheed W, Farrelly S et al. Randomised controlled trial of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment for people with psychosis: economic outcomes. PLoS ONE 2013;8:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Højlund M, Høgh L, Bojesen AB, Munk‐Jørgensen P, Stenager E. Use of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines in connection to minimising coercion and mechanical restraint in a general psychiatric ward. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Putkonen A, Kuivalainen S, Louheranta O et al. Cluster‐randomized controlled trial of reducing seclusion and restraint in secured care of men with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E, Fröhlich D et al. Aggression and violence in psychiatric hospitals with and without open door policies: a 15‐year naturalistic observational study. J Psychiatr Res 2017;95:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wanchek TN, Bonnie RJ. Use of longer periods of temporary detention to reduce mental health civil commitments. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huber CG, Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E et al. Suicide risk and absoconding in psychiatric hospitals with and without open door policies: a 15 year, observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:842–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bruckner TA, Yoon J, Brown TT, Adams N. Involuntary civil commitments after the implementation of California’s Mental Health Services Act. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Allen M. Waking Rip van Winkle: why developments in the last 20 years should teach the mental health system not to use housing as a tool of coercion. Behav Sci Law 2003;21:503–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Maylea C. Minimising coerciveness in coercion: a case study of social work powers under the Victorian Mental Health Act. Aus Soc Work 2017;70:465–476. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bariffi FJ, Smith MS. Same old game but with some new players – assessing Argentina’s National Mental Health Law in light of the rights to liberty and legal capacity under the un convention on the rights of the persons with disabilities. Nord J Hum Rights 2013;31:325–342. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Corlett S. Policy watch: a steady erosion of rights. Ment Health Soc Inclus 2013;17:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haycock J, Finkelman D, Presskreischer H. Mediating the gap: thinking about alternatives to the current practice of civil commitment symposium: therapeutic jurisprudence: from idea to application. N Eng J Crim Civ Confinement 1993;20:265–289. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Janssen WA, van de Sande R, Noorthoorn EO et al. Methodological issues in monitoring the use of coercive measures. Int J Law Psychiatry 2011;34:429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Høyer G, Kjellin L, Engberg M et al. Paternalism and autonomy: a presentation of a Nordic study on the use of coercion in the mental health care system. Int J Law Psychiatry 2002;25:93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gooding P, McSherry B, Roper C, Grey F.Alternatives to coercion in mental health settings: a literature review. Melbourne: Melbourne Social Equity Institute, University of Melbourne, 2018. Available from: https://socialequity.unimelb.edu.au/news/latest/alternatives-to-coercion [Accessed on 15 April 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Easterbrook PJ, Gopalan R, Berlin JA, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337:867–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Keski‐Valkama A, Sailas E, Eronen M, Koivisto AM, Lönngvist J, Kaltiala‐Heino R. A 15‐year national follow‐up: legislation is not enough to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Flammer E, Steinert T. Involuntary medication, seclusion, and restraint in German psychiatric hospitals after the adoption of legislation in 2013. Front Psychiatry 2015;6:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Flammer E, Steinert T. Impact of the temporary lack of legal basis for involuntary treatment on the frequency of aggressive incidents, seclusion and restraint among patients with chronic schizophrenic disorders. Psychiatr Prax 2015;42:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Flammer E, Steinert T. Association between restriction of involuntary medication and frequency of coercive measures and violent incidents. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:1315–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Federal Constitutional Court (Germany) . ‘Press Office ‐ Press Release No 28/2011 of 15 April 2011, Order of 23 March 2011’, 2 BvR 882/09.

- 74. Thomsen C, Starkopf L, Hastrup LH, Andersen PK, Nordentoft M, Benros ME. Risk factors of coercion among psychiatric inpatients: a nationwide register‐based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pollmächer T, Steinert T. Arbitrary classification of hospital policy regarding open and locked doors. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:1103–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Croft B, Isvan N. Impact of the 2nd story peer respite program on use of inpatient and emergency services. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bak J, Zoffmann V, Sestoft DM, Almvik R, Brandt‐Christensen M. Mechanical restraint in psychiatry: preventive factors in theory and practice. A Danish‐Norwegian association study. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2014;50:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Azeem MW, Aujla A, Rammerth M, Bingsfeld G, Jones RB. Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints at a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 2011;24:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ashcraft L, Bloss M, Anthony WA. Best practices: the development and implementation of “no force first” as a best practice. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:415–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bowers L, James K, Quirk A, Simpson A, Stewart D, Hodsoll J. Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: the safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1412–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. National Technical Assistance Center . Six core strategies to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint planning tool. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2005. Available from: https://www.nasmhpd.org/content/six-core-strategies-reduce-seclusion-and-restraint-use [Accessed 15 April 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bowers L. Safewards: a new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2014;21:499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mutafa FA. The safewards study lacks rigour despite its randomised design. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1906–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fletcher J, Spittal M, Brophy L et al. Outcomes of the Victorian safewards trial in 13 wards: impact on seclusion rates and fidelity measurement. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2017;26:461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lewis M, Taylor K, Parks J. Crisis prevention management: a program to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in an inpatient mental health setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2009;30:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Huber CG, Schneeberger AR, Kowalinski E et al. Arbitrary classification of hospital policy regarding open and locked doors – authors’ reply. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:1103–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bowers L, Haglund K, Muir‐Cochrane E, Nijman H, Simpson A, Van Der Merwe M. Locked doors: a survey of patients, staff and visitors. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2010;17:873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. van der Schaaf PS, Dusseldorp E, Keuning FM, Janssen WA, Noorthoorn EO. Impact of the physical environment of psychiatric wards on the use of seclusion. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lay B, Blank C, Lengler S, Drack T, Bleiker M, Rössler W. Preventing compulsory admission to psychiatric inpatient care using psycho‐education and monitoring: feasibility and outcomes after 12 months. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;265:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Janssen WA, Noorthoorn EO, Nijman HL et al. Differences in seclusion rates between admission wards: does patient compilation explain? Psychiatr Q 2013;84:39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Husum TL, Bjørngaard JH, Finset A, Ruud T. A cross‐sectional prospective study of seclusion, restraint and involuntary medication in acute psychiatric wards: patient, staff and ward characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Greenfield TK, Stoneking BC, Humphreys K, Sundby E, Bond J. A randomized trial of a mental health consumer‐managed alternative to civil commitment for acute psychiatric crisis. Am J Community Psychol 2008;42:135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Henderson C, Farrelly S, Flach C et al. Informed, advance refusals of treatment by people with severe mental illness in a randomised controlled trial of joint crisis plans: demand, content and correlates. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Henderson C, Flood C, Leese M, Thornicroft G, Sutherby K, Szmukler G. Effect of joint crisis plans on use of compulsory treatment in psychiatry: single blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004;329:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Henderson C, Flood C, Leese M, Thornicroft G, Sutherby K, Szmukler G. Views of service users and providers on joint crisis plans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;44:369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. van der Post LF, Peen J, Visch I, Mulder CL, Beekman AT, Dekker JJ. Patient perspectives and the risk of compulsory admission: the Amsterdam study of acute psychiatry V. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2014;60:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hackett R, Nicholson J, Mullins S, Farrington T, Ward S, Pritchard G. Enhancing pathways into care (EPIC): community development working with the Pakistani community to improve patient pathways within a crisis resolution and home treatment service. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009;21:465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Papageorgiou A, King M, Janmohamed A, Davidson O, Dawson J. Advance directives for patients compulsorily admitted to hospital with serious mental illness. Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Thornicroft G, Farrelly S, Szmukler G et al. Clinical outcomes of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment for people with psychosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:1634–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rose D, Perry E, Rae S, Good N. Service user perspectives on coercion and restraint in mental health. BJPsych Int 2017;14:59–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S et al. Assessing the Organizational Social Context (OSC) of mental health services: implications for research and practice. Adm Policy Ment Health 2008;35:98–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Aarons GA, Sawitzky AC. Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence‐based practice. Psychol Serv 2006;3:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]