Abstract

Background

In the Netherlands there is a lack of data regarding resistance of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius to the systemic antimicrobial drugs used for the treatment of superficial pyoderma.

Objectives

To assess antimicrobial resistance, with emphasis on resistance to clindamycin and meticillin, in clinical isolates of S. pseudintermedius isolated from dogs with superficial pyoderma. Results were compared between dogs with and without a history of systemic antimicrobial therapy during the previous year.

Animals

A retrospective study of 237 referral cases presented to an academic teaching hospital between 2014 and 2019, with the clinical and microbiological diagnosis of superficial pyoderma.

Methods and materials

All clinical isolates were identified primarily by MALDI‐TOF mass spectrometry. Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested either by an agar diffusion method (2014–2016) or by broth microdilution. Antimicrobial history in the preceding year was obtained from medical records.

Results

Meticillin‐resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) was isolated from 8% of superficial pyoderma cases. Within the meticillin‐susceptible S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) population, clindamycin resistance was significantly more common in isolates derived from dogs with histories of antimicrobial treatment (37.7%) compared to dogs with no histories of exposure (21.7%; P = 0.03).

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of clindamycin resistance in MSSP isolated from dogs with prior antimicrobial exposure, it is recommended that bacterial culture and susceptibility testing be pursued before prescribing systemic antimicrobials. Clindamycin should be regarded as the preferred treatment option if susceptibility is confirmed, due to its narrow spectrum and reduced selective pressure for MRSP.

Background – In the Netherlands there is a lack of data regarding resistance of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius to the systemic antimicrobial drugs used for the treatment of superficial pyoderma. Objectives – To assess antimicrobial resistance, with emphasis on resistance to clindamycin and meticillin, in clinical isolates of S. pseudintermedius isolated from dogs with superficial pyoderma. Results were compared between dogs with and without a history of systemic antimicrobial therapy during the previous year. Conclusions – Given the high prevalence of clindamycin resistance in MSSP isolated from dogs with prior antimicrobial exposure, it is recommended that bacterial culture and susceptibility testing be pursued before prescribing systemic antimicrobials. Clindamycin should be regarded as the preferred treatment option if susceptibility is confirmed, due to its narrow spectrum and reduced selective pressure for MRSP.

Résumé

Contexte

Aux Pays Bas, il y a un manque de données sur les résistances de Staphylococcus pseudintermedius aux antimicrobiens systémiques utilisés pour traiter les pyodermites superficielles.

Objectifs

Déterminer la résistance antimicrobienne avec emphase sur la résistance à la clindamycine et la méticiline, dans les souches cliniques de S. pseudintermedius isolées de chiens avec pyodermite superficielle. Les résultats ont été comparés entre les chiens avec et sans antécédents de traitements antimicrobiens au cours de l’année précédente.

Sujets

Une étude rétrospective de 237 cas référés présentés à un hôpital universitaire d’enseignement entre 2014 et 2019, avec le diagnostic clinique et microbiologique de pyodermite superficielle.

Matériel et méthode

Toutes les souches cliniques ont été identifiées par spectrométrie de masse MALDI‐TOF. La sensibilité antimicrobienne a été testée soit par diffusion sur disque d’agar (2014‐2016) soit par microdilution en milieu liquide. Les antécédents antimicrobiens au cours de l’année précédente ont été obtenus des données médicales.

Résultats

S. pseudintermedius résistant à la méticiline (MRSP) a été isolée de 8% des pyodermites superficielles. Au sein de la population de S. pseudintermedius sensible à la méticiline (MSSP), la résistance à la clindamycine était significativement plus fréquente dans les souches issues de chiens avec antécédents de traitement antimicrobien (37.7%) comparé aux chiens sans antécédent d’exposition (21.7%; P = 0.03).

Conclusions

Etant donné la prévalence élevée de résistance à la clindamycine au sein des MSSP isolées de chiens avec exposition antérieure à un antimicrobien, il est recommandé de réaliser une culture bactériologique avec antibiogramme avant de prescrire des antimicrobiens systémiques. La clindamycine devrait être considérée comme la meilleure option thérapeutique si la résistance est confirmée en raison de son spectre étroit et de la pression de sélection réduite pour MRSP.

RESUMEN

Introducción

en los Países Bajos faltan datos sobre la resistencia de Staphylococcus pseudintermedius a los medicamentos antimicrobianos sistémicos utilizados para el tratamiento de la pioderma superficial.

Objetivos

evaluar la resistencia a los antimicrobianos, con énfasis en la resistencia a clindamicina y meticilina, en aislados clínicos de S. pseudintermedius aislados de perros con pioderma superficial. Los resultados se compararon entre perros con y sin antecedentes de terapia antimicrobiana sistémica durante el año anterior.

Animales

estudio retrospectivo de 237 casos de referidos a un hospital universitario académico entre 2014 y 2019, con diagnóstico clínico y microbiológico de pioderma superficial.

Métodos y materiales

todos los aislados clínicos se identificaron principalmente por espectrometría de masas MALDI‐TOF. La susceptibilidad a los antimicrobianos se probó mediante un método de difusión en agar (2014‐2016) o mediante microdilución en caldo. La historia de tratamiento con antimicrobianos en el año anterior se obtuvo de los historiales clínicos.

Resultados

se aisló S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) resistente a meticilina del 8% de los casos de pioderma superficial. Dentro de la población de S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) susceptible a meticilina, la resistencia a la clindamicina fue significativamente más común en aislamientos derivados de perros con antecedentes de tratamiento antimicrobiano (37,7%) en comparación con perros sin antecedentes de exposición (21,7%; P = 0,03).

Conclusiones

Dada la alta prevalencia de resistencia a la clindamicina en MSSP aislado de perros con exposición antimicrobiana previa, se recomienda realizar un cultivo bacteriano y pruebas de susceptibilidad antes de prescribir antimicrobianos sistémicos. La clindamicina debe considerarse como la opción de tratamiento preferida si se confirma la susceptibilidad, debido a su espectro estrecho y la presión selectiva reducida para MRSP.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

In den Niederlanden besteht ein Mangel an Daten in Bezug auf die Resistenz von Staphylococcus pseudintermedius zu systemischen Antibiotika, die zur Behandlung einer oberflächlichen Pyodermie eingesetzt werden.

ZieleEine Erfassung der antimikrobiellen Resistenz mit Betonung der Resistenz auf Clindamycin und Methicillin bei klinischen Isolaten von S. pseudintermedius, welche von Hunden mit einer oberflächlichen Pyodermie isoliert werden konnten. Die Ergebnisse wurden zwischen den Hunden mit und ohne Anamnese einer systemischen Antibiotika Therapie während des vergangenen Jahres verglichen.

Tiere

Eine retrospektive Studie mit 237 Überweisungsfällen, die in einer akademischen veterinärmedizinischen Klinik zwischen 2014 und 2019 mit einer klinischen und mikrobiologischen Diagnose einer oberflächlichen Pyodermie vorgestellt wurden.

Methoden und Materialien

Alle klinischen Isolate wurden primär mittels MALDI‐Toff Massenspektrometrie identifiziert. Die Sensibilität auf Antibiotika wurde entweder mittels Agardiffusionsmethode (2014‐2016) oder mittels Bouillon‐Mikrodilution getestet. Die antimikrobielle Anamnese des vergangenen Jahres wurde den Krankenkarteien entnommen.

Ergebnisse

Methicillin‐resistente S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) wurden bei 8% der Fälle mit oberflächlicher Pyodermie isoliert. Innerhalb der Methicillin‐sensiblen S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) Population war eine Resistenz auf Clindamycin signifikant häufiger bei Isolaten von Hunden mit der Anamnese einer antibiotischen Behandlung (37,7%) im Vergleich zu Hunden ohne vorhergehende Antibiotika Behandlung (21,7%; P = 0,03) festzustellen.

Schlussfolgerungen

Angesichts der hohen Prävalenz einer Clindamycin Resistenz bei MSSP Isolaten von Hunden mit vorhergehender Antibiotika Behandlung, wird empfohlen, eine bakterielle Kultur und ein Antibiogramm vor dem Verschreiben von systemischen Antibiotika durchzuführen. Clindamycin sollte, wenn eine Sensibilität bestätigt wurde, aufgrund des engen Spektrums und des reduzierten selektiven Drucks für MRSP als bevorzugte Behandlungsoption betrachtet werden.

要約

背景

オランダでは、表在性膿皮症の治療に使用される全身性抗菌薬に対するStaphylococcus pseudintermediusの耐性に関するデータが不足している。

目的

本研究の目的は、表在性膿皮症に罹患した犬から分離されたS. pseudintermediusの臨床分離株について、クリンダマイシンおよびメチシリンに対する耐性を重視し抗菌剤耐性を評価することであった。前年の全身抗菌薬治療歴のある犬とない犬の結果を比較した。

被験動物

2014年から2019年の間に学術教育病院に紹介された237件の紹介症例の回顧的研究で、表在性膿皮症の臨床的および微生物学的診断が行われた。

材料と方法

すべての臨床分離株は、主にMALDI‐TOF質量解析によって同定された。抗菌薬感受性は、寒天拡散法(2014–2016)または微量液体希釈法のいずれかでテストした。前年の抗菌薬歴は医療記録から得られた。

結果

メチシリン耐性S. pseudintermedius(MRSP)は、表在性膿皮症症例の8%から分離された。メチシリン感受性のS. pseudintermedius(MSSP)集団内で、クリンダマイシン耐性は、抗菌薬治療歴のある犬(37.7%)由来分離株で、曝露歴のない犬(21.7%; P = 0.03)と比較して有意に多かった。

結論

以前に抗菌薬に曝露された犬から分離されたMSSPにおけるクリンダマイシン耐性の高い有病率を考えると、全身性抗菌薬を処方する前に、細菌培養と感受性試験を実施することを推奨する。クリンダマイシンは、そのスペクトルが狭く、MRSPの選択圧が低いため、感受性が確認された場合、好ましい治療オプションと見なされるべきである。

摘要

背景

在荷兰,关于治疗浅表性脓皮病的全身抗菌药,缺乏假中间型葡萄球菌的耐药性数据。

目的

评估从浅表性脓皮病患犬身上分离的假中间型葡萄球菌临床菌株, ,其对抗菌剂的耐药性,重点评估对克林霉素和甲氧西林的耐药性。比较了前一年有和无全身抗菌治疗史的犬之间的结果。

动物

对2014年至2019年间学院教学医院就诊的237例转诊病例进行了回顾性研究,这些病例基于临床和微生物学被诊断为浅表性脓皮病。

方法和材料

主要通过MALDI‐TOF质谱法鉴定所有临床分离株。通过琼脂扩散法(2014‐2016年)或微量肉汤稀释法检测抗菌药的敏感性。从病历中获得前一年的抗菌史。

结果

8%的浅表性脓皮病病例分离出耐甲氧西林假中间型葡萄球菌 (MRSP)。在甲氧西林敏感的假中间型葡萄球菌 (MSSP) 菌群中,与无用药史的犬(21.7%;P=0.03)相比,有抗菌治疗史的犬(37.7%),其对克林霉素明显更常见耐药性。

结论

考虑到有抗菌剂治疗史的犬身上分离出的MSSP,其对克林霉素的高耐药率,建议在给予全身性抗菌剂之前,进行细菌培养和药敏试验。克林霉素是窄谱抗生素,可以降低MRSP的选择压力,因此,如果证实了克林霉素的敏感性,应将其视为首选治疗药。

Resumo

Contexto

Na Holanda, faltam dados sobre a resistência do Staphylococcus pseudintermedius aos medicamentos antimicrobianos sistêmicos utilizados no tratamento da piodermite superficial.

Objetivos

Avaliar a resistência antimicrobiana, com ênfase na resistência à clindamicina e meticilina, em isolados clínicos de S. pseudintermedius isolados de cães com piodermite superficial. Os resultados foram comparados entre cães com e sem histórico de terapia antimicrobiana sistêmica no ano anterior.

Animais

Estudo retrospectivo de 237 casos de referência apresentados em um hospital universitário entre 2014 e 2019, com diagnóstico clínico e microbiológico de piodermite superficial.

Métodos e materiais

Todos os isolados clínicos foram identificados primeiramente por espectrometria de massa MALDI‐TOF. A suscetibilidade antimicrobiana foi testada pelo método de difusão em ágar (2014–2016) ou por microdiluição em caldo. O histórico do uso de antimicrobianos no ano anterior foi obtido nos prontuários médicos.

Resultados

S. pseudintermedius resistente à meticilina (MRSP) foi isolado em 8% dos casos superficiais de piodermite. Na população de S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) suscetível à meticilina, a resistência à clindamicina foi significativamente mais comum em isolados oriundos de cães com histórico de tratamento antimicrobiano prévio (37,7%) em comparação com cães sem histórico de exposição (21,7%; P = 0,03).

Conclusões

Dada a alta prevalência de resistência à clindamicina nos MSSP isolados de cães com exposição antimicrobiana prévia, recomenda‐se que a cultura bacteriana e os testes de sensibilidade sejam realizados antes da prescrição de antimicrobianos sistêmicos. A clindamicina deve ser considerada como a opção de tratamento de escolha se a suscetibilidade for confirmada, devido ao seu espectro estreito e pressão seletiva reduzida para a MRSP.

Introduction

The commensal and opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is the most frequently isolated bacterial pathogen in canine pyoderma. 1 Due to the worldwide emergence of meticillin‐resistant staphylococci, responsible antimicrobial use is of paramount importance to maintain clinical efficacy of current antimicrobials. 2 According to international guidelines, clindamycin, lincomycin, trimethoprim‐potentiated sulphonamides (TMPS), first generation cephalosporins and amoxicillin‐clavulanate are indicated as empirical antibiotics of choice for systemic treatment. 3 However, the Dutch national guidelines indicate a slightly different classification with only clindamycin listed as an empirical option (Table 1). 4 Compared to β‐lactam antibiotics, clindamycin shows, along with a narrow spectrum for mainly Gram‐positive bacteria, a lower selective pressure for meticillin‐resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) which is the fundamental reason that clindamycin is recommended for empirical therapy. 3 However, according to an extensive review, the published resistance of meticillin‐sensitive S. pseudintermedius (MSSP) against clindamycin within Europe shows a wide range (7–98%). 5

Table 1.

Classification of veterinary antimicrobial agents used for canine superficial pyoderma according to Dutch policy on antimicrobial use

| Classification | Systemic antimicrobials | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| 1st choice | Clindamycin | Empirical therapy |

| 2nd choice |

Amoxicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate and first‐ and second generation cephalosporins |

Antimicrobials not classified as 1st or 3rd choice antimicrobials. Do not use, unless there is a good clinical motivation to not use the 1st choice. |

| 3rd choice |

Fluoroquinolones and third‐ and fourth generation cephalosporins |

By Dutch law restricted to use only after culture and susceptibility testing shows resistance to 1st and 2nd choice antimicrobials |

| Never allowed | Carbapenems, glycopeptide antimicrobials, oxazolidinone, daptomycin, mupirocin and tigecycline | By Dutch law restricted to use only as last resort antimicrobial in people |

Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in animal pathogens at a national level is urgently needed in order to formulate evidence‐based antimicrobial prescribing guidelines, which may vary by locality. 5 A surveillance system for antimicrobial resistance in animal pathogens is not available in the Netherlands.

The main objective of this retrospective study was to assess the prevalence of resistance to systemic antimicrobial drugs, with an emphasis on clindamycin, in S. pseudintermedius isolates derived from cases of canine superficial pyoderma. A comparison between dogs that had and had not received systemic antimicrobial therapies within the past 12 months was sought, with the intention of making recommendations for refinement of the Dutch national guidelines. Such data are key to promoting prudent antimicrobial use within the Netherlands and also may contribute to international perspectives on responsible antimicrobial stewardship.

Methods and materials

Study design

Medical records of dogs referred to the Dermatology Service of the Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals between January 2014 and January 2019 were retrospectively evaluated. Only dogs that were initially presented with clinical signs compatible with superficial pyoderma (papules, pustules and/or epidermal collarettes) and confirmed by bacterial culture showing moderate to profuse growth of S. pseudintermedius, were included. If multiple samples had been obtained from one dog, only the S. pseudintermedius isolate from the first presentation was analysed. Prior use of antimicrobial drugs was assessed using the medical record from the referring veterinary practice. Dogs were divided into two groups: those with no history of systemic antimicrobial use over the previous 12 months and those with documented exposure. Data were included in the analysis only for MSSP and if a dog had a known antimicrobial‐use history.

Specimen collection, microbe identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

A standardized laboratory protocol was used between 2014 and 2019. Specimen collection was performed using sterile transport swabs (Copan; Brescia, Italy) from pustules if these were present, or papules or epidermal collarettes according to the guidelines. 3 Bacterial infection was confirmed based on bacterial culture at the Veterinary Microbiological Diagnostic Center (VMDC) of (Utrecht University). Samples were cultured on sheep blood agar (bioTRADING; Mijdrecht, the Netherlands) overnight at 37°C. Before August 2014, presumptive colonies were identified as S. pseudintermedius using phenotypic and biochemical tests. From August 2014 onwards, identification of presumptive colonies was confirmed by matrix‐assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI‐TOF MS, Bruker; Delft, the Netherlands).

Up to August 2016, antimicrobial susceptibility was tested by an agar diffusion method using Neo‐Sensitabs (Rosco; Taastrup, Denmark). From August 2016 onwards, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by broth microdilution using a commercially available automated MICRONAUT system incorporating a custom‐made panel for routine diagnostic testing at the VMDC (MERLIN Diagnostika GmbH; Bonn, Germany). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed as recommended by the manufacturer for inoculum preparation, broth composition and incubation conditions. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 was used as a quality control strain. The results were read automatically using a photometer (MERLIN Diagnostika GmbH). Veterinary breakpoints were used according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 6 when available. When veterinary breakpoints were unavailable for S. pseudintermedius, breakpoints for other Staphylococci or human breakpoints were used. 7 , 8 Screening for meticillin resistance was performed using oxacillin susceptibility testing and confirmed by mecA real‐time PCR. Antimicrobial agents used in the susceptibility analysis for S. pseudintermedius included ampicillin (representing also amoxicillin), amoxicillin/clavulanate, first‐ and third‐generation cephalosporins (cephalothin and ceftiofur), clindamycin, tetracycline (representing also doxycycline), trimethoprim‐sulfur (TMP/S) and enrofloxacin. Isolates (n = 7) showing erythromycin‐clindamycin discordance (erythromycin resistance and clindamycin susceptibility) were subjected to D‐zone testing. 6 Inducible clindamycin resistance was not detected.

Statistical analysis

Cross contingency tabulations with Fisher’s exact test were used to compare percentages of resistance between groups. P‐values < 0.05 were considered significant. Ninety‐five percent confidence intervals were calculated based on the modified Wald method. Differences in baseline characteristics between dogs were calculated with a chi‐square test. All analyses were performed with prism v8.2.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

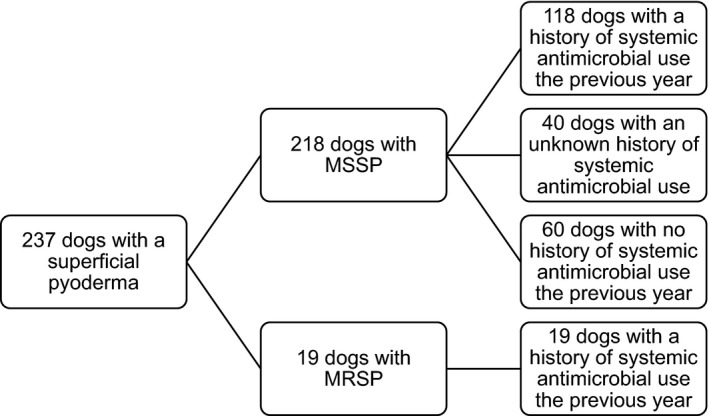

A total of 134 males (56 of which were neutered) and 103 females (77 of which were spayed), were included with a median age of 5.2 years (range three months to 16 years; Figure 1). From the 218 MSSP‐positive dogs, 40 dogs had an unknown treatment history and were excluded from the analysis of antimicrobial resistance in relation to the antimicrobial treatment history. From the 178 MSSP‐positive dogs with a known treatment history, 118 (66.3%) had received antimicrobials (mean 1.9 treatments: range 1–6 treatments). Of the prescribed antimicrobial treatments, 11% consisted of clindamycin and 75% consisted of a ß‐lactam drug.

Figure 1.

Number of dogs in the study per group, indicating (meticillin‐resistant) Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and treatment history.

MSSP meticillin‐sensitive S. pseudintermedius; MRSP meticillin‐resistant S. pseudintermedius.

Nineteen dogs (8.0%) were MRSP‐positive. These dogs had received on average 1.8 antimicrobial treatments in the preceding year (range 1–4 treatments). High rates of resistance (>80%) to clindamycin, doxycycline and TMP/S were detected in the MRSP isolates. The antimicrobial resistance to fluoroquinolones was much lower (<40%).

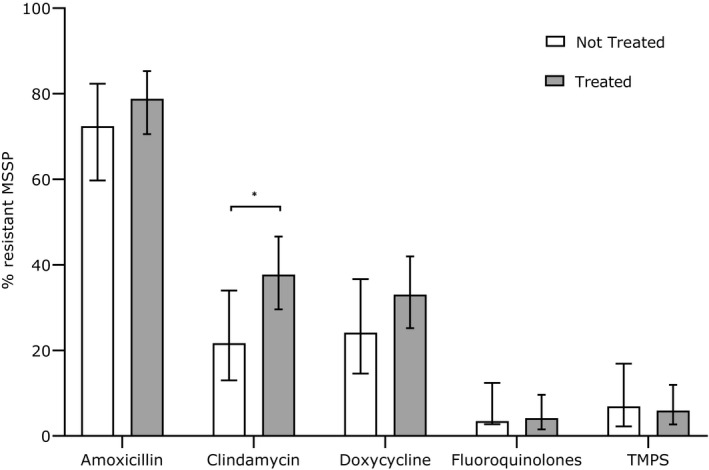

Overall resistance rates of MSSP (n = 218) for systemic antimicrobials were: amoxicillin 76.7%; clindamycin 32.4%; cephalosporins and amoxicillin‐clavulanate 0%; doxycycline 30.1%; fluoroquinolones 3.9%; and TMP/S 6.3%. There were no significant differences in MSSP resistance rates for any drug other than clindamycin, when dogs with antimicrobial exposure histories were compared to those without prior exposure (Figure 2). Clindamycin resistance in isolates from dogs with a prior history of antimicrobial use (37.7%) was significantly higher than in isolates from dogs that had not received antimicrobial therapy within the preceding 12 months (21.7%; P = 0.03). There were no other significantly different patient‐level factors between dogs with clindamycin‐susceptible and clindamycin‐resistant MSSP.

Figure 2.

Resistance percentage of meticillin‐sensitive Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MSSP) against amoxicillin, clindamycin, trimethoprim‐potentiated sulphonamides (TMPS), doxycycline and fluoroquinolones.

No resistance of MSSP against amoxicillin‐clavulanate and first‐ and third‐generation cephalosporins was recorded in dogs with a known history of antimicrobial use (n = 178). Error bars illustrate 95% confidence intervals (*P < 0.05). White columns represent the dogs with no antibiotic history and grey columns represent the dogs who had received systemic antimicrobials within the past 12 months.

Discussion

This study has revealed a high rate of clindamycin resistance (37.7%) in MSSP isolates from dogs with superficial pyoderma after receiving systemic antimicrobial therapy within the 12 months before sampling. Prior studies from Denmark and Sweden reported clindamycin resistance of MSSP just below 30% in dogs with a systemic or unknown antimicrobial exposure histories, and resistance rates between 13% and 14% in dogs without histories of systemic antimicrobial exposures. 9 , 10 A higher prevalence of clindamycin resistance in dogs that had received antimicrobial drug therapy (42.9%) compared to dogs without prior antimicrobial treatment (20.6%) was first reported in the late 1970s from the USA. 11

The high rate of resistance to amoxicillin (76.7%) in MSSP isolates in this study are consistent with rates of resistance to the (amino) penicillins reported worldwide. 5 An adjustment of the Dutch guidelines (to now exclude amoxicillin and ampicillin as possible treatment options) would be prudent. The overall prevalence of MRSP reported from continental European clinical laboratory samples has ranged from 7% (the Netherlands) to 14% (Finland) and 32% (Italy). 12 , 13 , 14 The prevalence of MRSP reported in the current study (8.0%) is consistent with the prior Dutch report.

A primary limitation of this study is that it was performed within a referral dermatology clinic. Therefore, the authors recommend that surveillance for antimicrobial resistance should be performed in a primary care population to better represent community prevalence rates. Still, the key findings of this study are a high relative rate of MSSP resistance to clindamycin when isolated from dogs with a history of antimicrobial therapy and a rather low prevalence of meticillin resistance compared to other European countries.

In conclusion, based on our findings, we recommend that the empirical use of clindamycin in dogs with histories of prior antimicrobial therapy be tempered. We instead recommend that bacterial culture and susceptibility testing be performed before prescribing systemic antimicrobial therapy in this population. If antimicrobial susceptibility testing confirms susceptibility of S. pseudintermedius to clindamycin, this drug should still be regarded as a preferred treatment option due to its narrow spectrum and reduced selective pressure for acquisition of MRSP.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Eveline van Vliet for data collection.

Sources of Funding: This study was self‐funded.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest have been declared.

References

- 1. Bannoehr J, Guardabassi L. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the dog: taxonomy, diagnostics, ecology, epidemiology and pathogenicity. Vet Dermatol 2012; 23: 253‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morris DO, Loeffler A, Davis MF et al. Recommendations for approaches to meticillin‐resistant staphylococcal infections of small animals: diagnosis, therapeutic considerations and preventative measures. Clinical Consensus Guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 304‐e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hillier A, Lloyd DH, Weese JS et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases). Vet Dermatol 2014; 25: 163–e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dutch Working Party on Veterinary Antibiotic Policy . WVAB‐richtlijn classificatie van veterinaire antimicrobiële middelen, 2015 and Formulary companion animals: dog, cat and rabbit 2017. Available at: https://www.knmvd.nl/app/uploads/sites/4/2018/09/Formularium‐Hond‐en‐Kat.pdf. Accessed Mar 1, 2020.

- 5. Moodley A, Damborg P, Nielsen SS. Antimicrobial resistance in methicillin susceptible and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius of canine origin: literature review from 1980 to 2013. Vet Microbiol 2014; 171: 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CLSI . Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; approved standards, 4th edition. CLSI document VET01‐A4. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. CLSI . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 27th edition. CLSI document Supplement M100S. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 8.0 (2018). Available at: www.eucast.org (Accessed March 01, 2020).

- 9. Larsen R, Boysen L, Berg J et al. Lincosamide resistance is less frequent in Denmark in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from first‐time canine superficial pyoderma compared with skin isolates from clinical samples with unknown clinical background. Vet Dermatol 2015; 26: 202–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holm BR, Petersson U, Morner A et al. Antimicrobial resistance in staphylococci from canine pyoderma: a prospective study of first‐time and recurrent cases in Sweden. Vet Rec 2002; 151: 600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ihrke PJ, Halliwell REW, Deubler MJ. Canine pyoderma In: Bonagura JD. ed. Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy Small Animal Practice VI. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1977; 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duim B, Verstappen KM, Broens EM et al. Changes in the population of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and dissemination of antimicrobial‐resistant phenotypes in the Netherlands. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54: 283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gronthal T, Eklund M, Thomson K et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and the molecular epidemiology of methicillin‐resistant S. pseudintermedius in small animals in Finland. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 1,021–1,030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menandro ML, Dotto G, Mondin A et al. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius from symptomatic companion animals in Northern Italy: Clonal diversity and novel sequence types. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2019; 66: 101331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]