SUMMARY

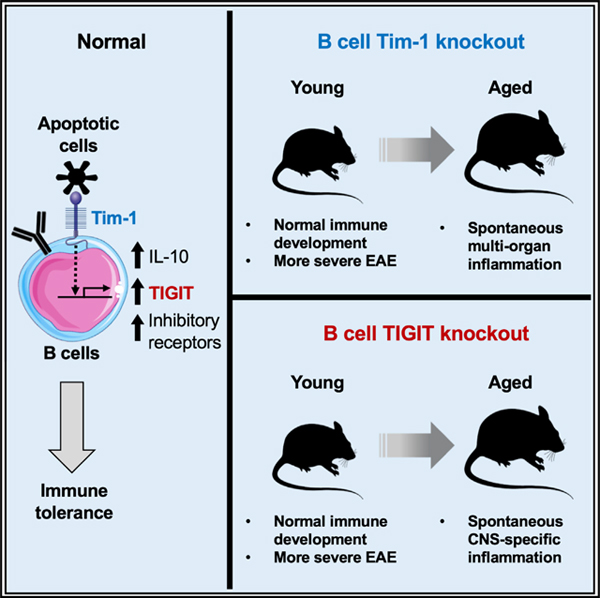

Tim-1, a phosphatidylserine receptor expressed on B cells, induces interleukin 10 (IL-10) production by sensing apoptotic cells. Here we show that mice with B cell-specific Tim-1 deletion develop tissue inflammation in multiple organs including spontaneous paralysis with inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS). Transcriptomic analysis demonstrates that besides IL-10, Tim-1+ B cells also differentially express a number of co-inhibitory checkpoint receptors including TIGIT. Mice with B cell-specific TIGIT deletion develop spontaneous paralysis with CNS inflammation, but with limited inflammation in other organs. Our findings suggest that Tim-1+ B cells are essential for maintaining self-tolerance and restraining tissue inflammation, and that Tim-1 signaling-dependent TIGIT expression on B cells is essential for maintaining CNS-specific tolerance. A possible critical role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in regulating the B cell function is discussed, as we find that AhR is among the preferentially expressed transcription factors in Tim-1+ B cells and regulates their TIGIT and IL-10 expression.

In Brief

Xiao et al. find that Tim-1 expression and signaling in B cells is required for maintaining self-tolerance. Tim-1+ B cells execute their regulatory function by expressing a set of negative immune regulators, of which checkpoint receptor TIGIT is preferentially required for the B cell-mediated tolerance in the central nervous system.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tim-1 is expressed in immune cells and regulates their responses in a cell intrinsic manner (Kuchroo et al., 2008; Rennert, 2011). Tim-1+ B cells can suppress effector T cell responses in experimental models of autoimmunity, allograft rejection, and allergic airway inflammation (Ding et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2012, 2015; Yeung et al., 2015). As a phosphatidylserine receptor, Tim-1 expression on B cells is required for optimal interleukin 10 (IL-10 production by binding to apoptotic cells (ACs; Xiao et al., 2015), and IL-10+ B cells are enriched within Tim-1+ cells in both mice and humans (Ding et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2012, 2015). Dysregulated IL-10+Tim-1+ B cell populations have been associated with inflammatory diseases in humans (Ma et al., 2014; Aravena et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2017; Kristensen et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2014; Mao et al., 2017). Although IL-10 has been suggested as a primary effector for the regulatory function of B cells, nevertheless mice with B cell-specific IL-10 deletion do not develop spontaneous inflammation with age (Madan et al., 2009). We previously reported that Tim-1 mutant mice developed sporadic spontaneous inflammation in multiple organs; however, from these studies it was not clear whether the effect was solely due to loss of Tim-1 function on B cells and what was the molecular mechanism by which Tim-1+ B cells mediated their regulatory function. Here we have provided evidence supporting that Tim-1+ B cells, whose function requires Tim-1 expression and signaling, are critical for maintaining self-tolerance and limiting tissue inflammation and that this non-redundant regulatory function for Tim-1+ B cells is partly mediated by expressing the checkpoint receptor TIGIT.

RESULTS

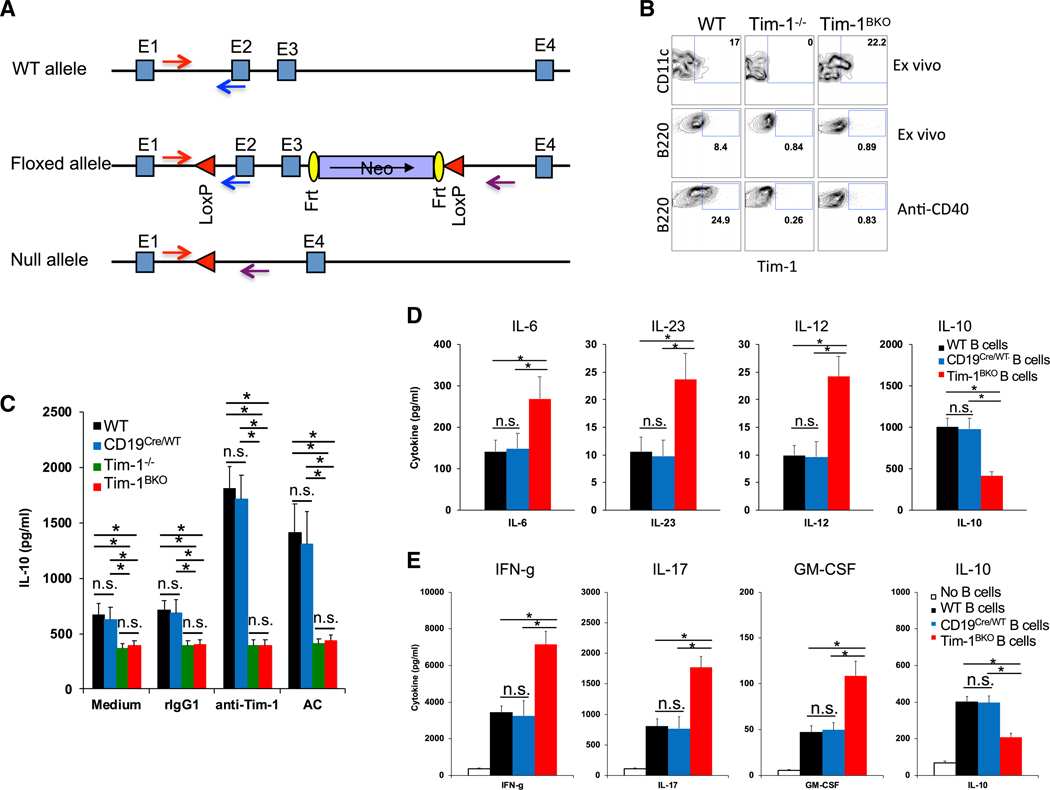

Tim-1BKO Mice Develop Spontaneous Multi-organ Tissue Inflammation with Age

To firmly evaluate the role of Tim-1 in B cells, we generated Tim-1 floxed (Tim-1fl/fl) mice (Figure 1A) and crossed them with CD19Cre/Cre mice (Rickert et al., 1997) to produce CD19Cre/WTTim-1fl/fl (Tim-1BKO) mice. We confirmed that Tim-1 was effectively deleted only in B cells in Tim-1BKO mice (Figure 1B); Tim-1BKO B cells stimulated with anti-Tim-1 or ACs had both reduced basal and induced IL-10 production (Figure 1C); LPS-activated Tim-1BKO B cells produced less IL-10, but more proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-23, and IL-12 (Figure 1D). Consequently, Tim-1BKO B cells as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) promoted T cell production of the inflammatory cytokines interferon γ (IFN-γ), IL-17, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), but inhibited IL-10 production (Figure 1E). The data support that Tim-1 expression on B cells determines inflammatory cytokine responses.

Figure 1. Generation of Tim-1BKO Mice.

(A) Strategy for generating Tim-1 floxed mice.

(B) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots showing Tim-1 expression in dendritic cells (DCs) and B cells in spleens of 6- to 8-week-old mice (n = 6–8) ex vivo or in isolated B cells activated with anti-CD40 for two days.

(C) B cells isolated from 6- to 8-week-old mice (n = 5–6 per group) were cultured with anti-Tim-1, apoptotic cells (ACs), or controls. After 60 h, IL-10 production in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA.

(D) B cells isolated from 6- to 8-week-old mice (n = 5–8 per group) were cultured with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 40 h and then examined for their cytokine production in culture supernatants by BioLegend LEGENDplex.

(E) Foxp3− T cells from 6- to 8-week-old Foxp3-GFP knockin (KI) mice were cultured with B cells from WT or Tim-1BKO mice (n = 5 per group) plus soluble anti-CD3 for three days. Then, isolated T cells from the cultures were re-activated with plate-bound anti-CD3, and cytokine production in 40-h cultures was measured by BioLegend LEGENDplex. *p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

See also Figure S1.

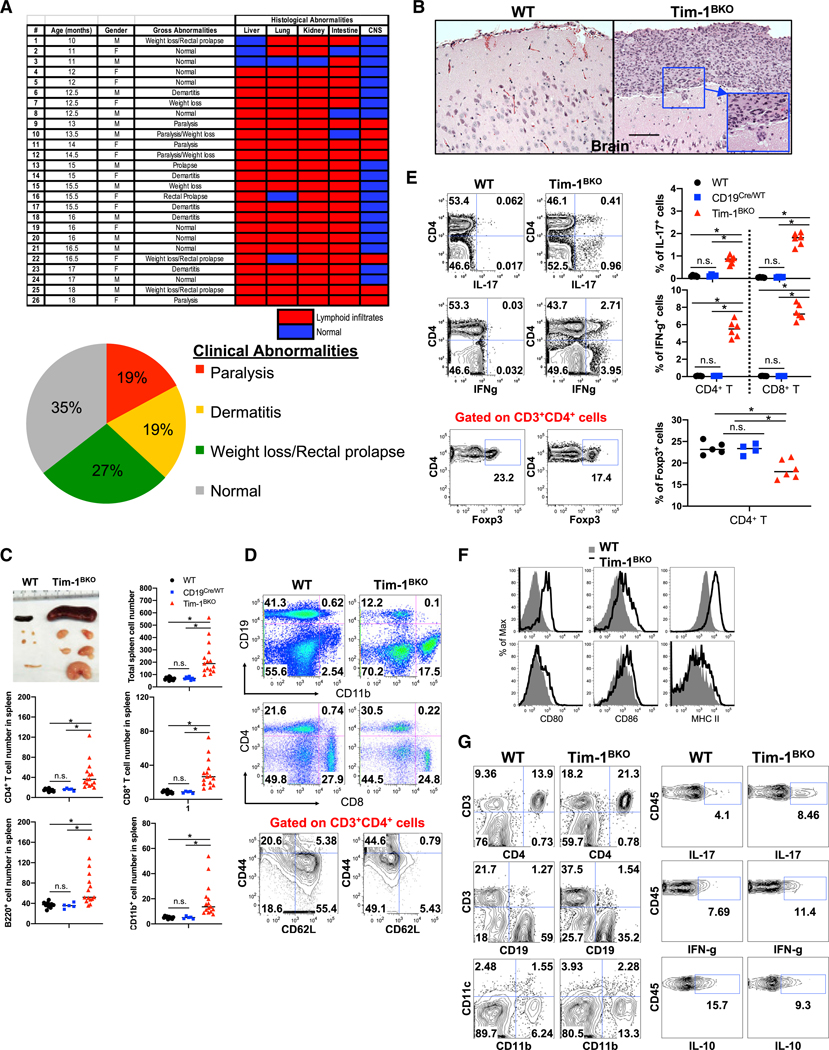

Tim-1BKO mice at <6 months of age appeared normal clinically and histologically, and did not display gross differences in T/B cells, macrophages, or dendritic cells (Figure S1). Interestingly, with age Tim-1BKO mice developed multi-organ tissue inflammation. About 65% of 10+-months-old Tim-1BKO mice showed clinical abnormalities, including weight loss and/or rectal prolapse (27%), dermatitis (19%), and strikingly, spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-like paralytic disease (19%; Figure 2A). Histological examination of livers, lungs, kidneys, intestines, and central nervous system (CNS) showed that 100% of aged Tim-1BKO mice had immune cell infiltrates in one or more of these organs: liver (88.5%), lungs (88.5%), kidney (96.2%), intestines (92.3%), and CNS (26.9%; Figures 2A, 2B, and S2). Some Tim-1BKO mice with paralysis displayed meningeal granulomatous inflammation in the CNS with Touton giant cells, whose appearance is indicative of hyperactivation of proinflammatory myeloid cells (Figure 2B).These data suggest that with age, loss of Tim-1 expression in B cells leads to a broad defect in maintenance of tolerance in multiple organs and tis- sues, even including the CNS.

Figure 2. Aged Tim-1BKO Mice Develop Spontaneous Tissue Inflammation.

(A) Table and graphs summarize clinical and histological abnormalities in 10- to 18-month-old Tim-1BKO mice.

(B) A Tim-1BKO mouse (#12 in A showed granulomatous inflammation in brain leptomeninges. Boxed area indicates a Touton giant cell shown at higher magnification. Bar, 100 μm.

(C) Tim-1BKO mice showed enlarged spleens and lymph nodes (LNs). Total splenocyte numbers were determined by trypan blue exclusion.

(D) Representative FACS plots showing phenotypes of immune cells (upper and middle panels) and CD4+ T cell activation (lower panels, gated CD3+CD4+ cells).

(E) Representative FACS plots showing phenotypes of T cell cytokine production (upper and middle panels, gated CD3+ cells) and Foxp3+ Tregs (lower panels, gated CD3+CD4+ cells).

(F) Representative FACS plots showing phenotypes of B cells (upper panel, gated CD19+ cells) and DCs (lower panel, gated CD11c+ cells) in LNs from control and Tim-1BKO mice (n = 5–15).

(G) Representative FACS data showing immune cell phenotypes in colonic LP of Tim-1BKO mice (n = 4). (Left panels) Gated CD45+ cells. (Right panels) Gated CD45+CD3+CD4+cells. *p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

See also Figure S2.

Aged Tim-1BKO mice also had lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly with a 2- to 8-fold increase in immune cells, predominantly CD11b+ cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and B220+ B cells, compared to control (wild-type [WT], CD19Cre/WT, and CD19Cre/WTTim-1fl/WT) mice (Figures 2C and 2D). T cells from the Tim-1BKO mice displayed a more activated/memory-like phenotype (CD44hiCD62Llow; Figure 2D) with increased IFN-γ and IL-17 production, but decreased frequency of Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 2E). Aged Tim-1BKO mice also displayed increased activation of CD11c+ dendritic cells and especially B cells, with increased expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II and costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 (Figure 2F). Tim-1BKO mice with rectal prolapse showed predominantly increased T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells in colonic lamina propria, and their CD4+ T cells produced more IFN-γ and IL-17 but less IL-10 (Figure 2G). Thus, B cell expression of Tim-1 is required for maintenance of tolerance, and loss of Tim-1 expression in the B cells results in the development of multi-organ inflammation accompanied by increased activation of and production of proinflammatory cytokines by T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells.

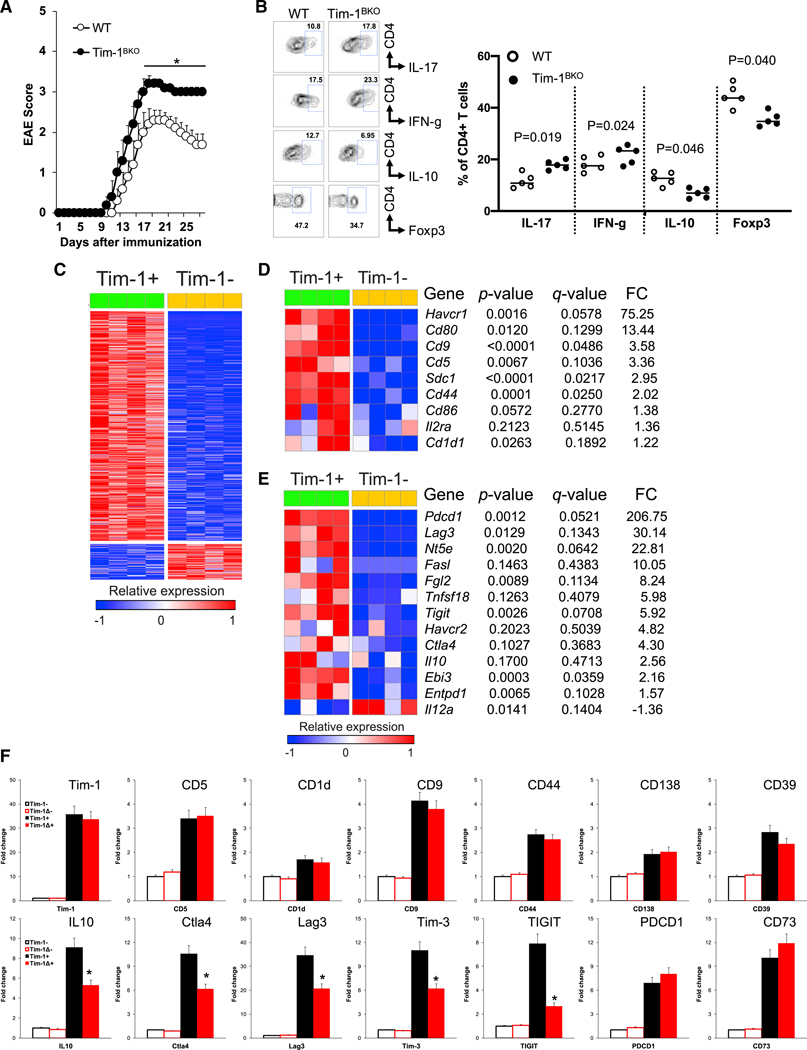

Tim-1BKO Mice Develop More Severe MOG35–55-Induced EAE

As aged Tim-1BKO mice developed spontaneous paralysis with inflammation in the CNS, we asked whether B cell deficiency of Tim-1 would affect EAE induction in young mice that did not yet display inflammation. Indeed, following immunization with MOG35–55, young Tim-1BKO mice developed more severe clinical signs of EAE with poorer recovery (Figures 3A and S3A), associated with increased frequencies of IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ T cells, and reduced frequencies of Foxp3+ Tregs and IL-10+ T cells in the CNS (Figure 3B), supporting our previous observation that B cell Tim-1 expression is essential for regulating the balance of proinflammatory Th1/Th17 cells and regulatory Foxp3+ Tregs and IL-10+ Tr1 cells (Xiao et al., 2015), and thus the development of autoimmunity.

Figure 3. Young Tim-1BKO Mice Develop More Severe EAE, and Tim-1+ B Cells Differentially Express a Set of Co-inhibitory Molecules besides IL10.

(A) 6- to 8-week-old mice were immunized with MOG35–55/CFA (Complete Freund’s Adjuvant) and scored daily for clinical EAE signs (n = 10/group). *p < 0.05.

(B) Thirty days after EAE induction, Foxp3 and cytokine expression in CNS-infiltrating CD4+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry.

(C) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq analysis of splenic Tim-1− and Tim-1+ B cells from 8-week-old naive WT mice (asymptotic Student’s t test p ≤ 0.05, absolute fold change ≥ 2).

(D) Heatmap of selected genes from (C) showing expression of known cell surface molecules associated with IL-10+ B cell subsets in Tim-1+ versus Tim-1− B cells.

(E) Heatmap of selected genes from (C) showing expression of well-known negative immune regulators in Tim-1+ versus Tim-1− B cells.

(F) qPCR data of selected genes in WT Tim-1−and Tim-1+ B cells and Tim-1Δmucin− and Tim-1Δmucin+ B cells, normalized to expression in WT Tim-1− B cells. *p < 0.01 (Tim-1+ versus Tim-1Δmucin+ cells; n = 4). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S3.

Tim-1+ B Cells Highly Express a Set of Negative Immune Regulators besides IL-10

To gain more insights into the mechanism by which Tim-1+ B cells mediate their inhibitory function, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on highly purified Tim-1+ and Tim-1− B cells from naive WT mice. Of the 15,519 genes detected, 888 were significantly differentially expressed between Tim-1+ and Tim-1− B cells–768 genes were upregulated in Tim-1+ B cells, while 120 were downregulated (Figure 3C). Interestingly, besides expressing Tim-1 and IL10, Tim-1+ B cells also express many of the molecules that have previously been identified as markers for various IL-10+ Breg cell populations (e.g., CD9, CD25, CD44/CD138, and CD5/CD1d; Mauri and Menon, 2015; Sun et al., 2015) or as important for the function of IL-10+ B cells (e.g., CD80 and CD86; Mann et al., 2007; Figure 3D). In addition to IL10, Tim-1+ B cells also highly expressed a panel of other negative immune modulators including Ebi3 (a subunit of IL-27), Entpd1 (encoding CD39), Nt5e (encoding CD73), Gitrl, and Fgl2. Interestingly, Tim-1+ B cells also highly expressed a set of checkpoint receptors including Tigit, CTLA4, Lag3, Pdcd1 (encoding PD-1), and Havcr2 (encoding Tim-3; Figures 3E and S3B) that have been associated with CD8+ T cell exhaustion/dysfunction and with Treg function, and therefore with self-tolerance and regulation of inflammation and autoimmunity (Anderson et al., 2016; Joller et al., 2012; Kuchroo et al., 2014).

Tim-1Δmucin is a loss-of-function Tim-1 mutant still expressed on the cell surface and can be stained with anti-Tim-1 (Xiao et al., 2012, 2015), thus providing a valuable tool for identifying Tim-1Δmucin+ cells and for studying the effect of loss of Tim-1 signaling on B cell function. Using B cells from Tim-1Δmucin mice, we found that loss of Tim-1 signaling (Tim-1Δmucin) did not alter expression of those genes previously identified as markers for various IL-10+ B cell subsets (e.g., CD9, CD5/CD1d, and CD138/CD44) or some genes previously reported to be involved in B cell regulatory function (e.g., Entpd1, Nt5e, Gitrl, and Ebi3). Interestingly however, in addition to IL10, expression of the checkpoint receptors Tigit, Tim-3, Lag3, and Ctla4, but not Pdcd1, was significantly reduced in Tim-1Δmucin+ cells, of which Tigit expression was most dramatically reduced (Figure 3F), indicating that their expression requires Tim-1 signaling. As Tim-1+ B cells highly express IL-10 as well as a panel of negative immune regulators, this suggests that Tim-1+ B cells may maintain self-tolerance and suppress inflammation by using multiple regulatory mechanisms, e.g., by expressing checkpoint receptors.

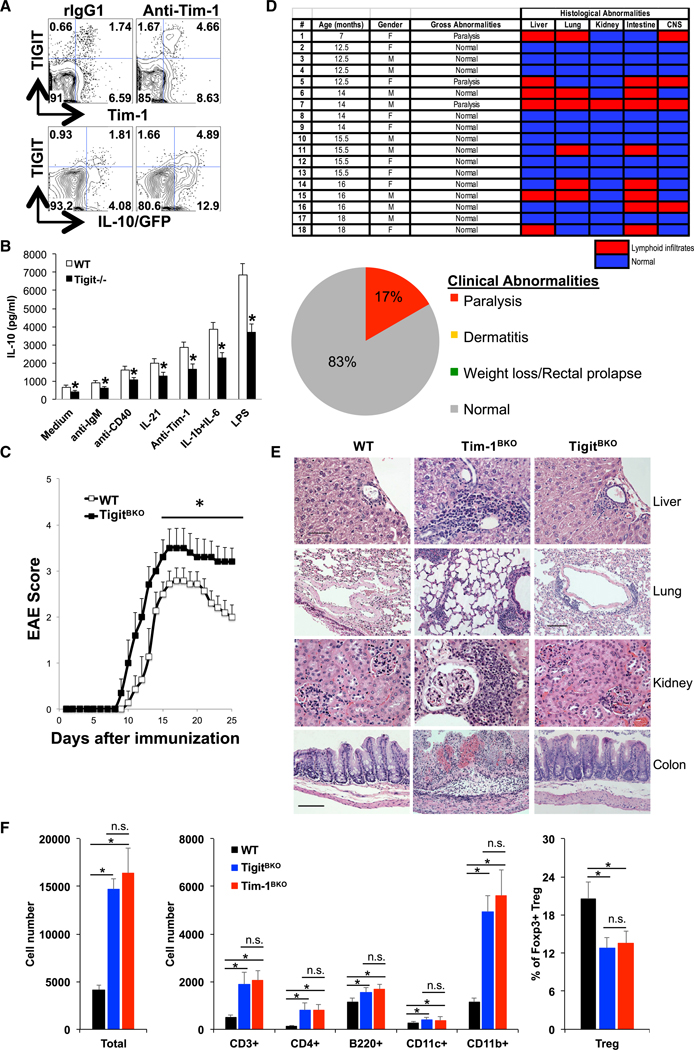

Role of TIGIT in B Cell Function

TIGIT is expressed on natural killer (NK) and T cells and is important for regulating immune responses in autoimmunity and cancer (Anderson et al., 2016; Joller et al., 2012; 2014). Here we found that TIGIT was also expressed in B cells and enriched in Tim-1+ B cells (Figures 3E and 3F). Tim-1 ligation with an anti-Tim-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) increased TIGIT expression and IL-10 production from B cells (Figure 4A), supporting the idea that Tim-1 signaling in B cells positively regulates TIGIT and IL-10 expression. Interestingly, we found that AhR is preferentially expressed in Tim-1+ B cells and required for their regulatory function. and for Tim-1-mediated expression of TIGIT and IL-10 by directly binding to their promoters in the B cells (Figure S4). Although TIGIT and IL-10 are mostly co-expressed, about 25% to 30% of TIGIT+ B cells are IL-10− and many of the IL-10+ cells are TIGIT−, indicating that expression of TIGIT and IL-10 can be separable events. Interestingly, while IL-10 blockade with anti-IL-10 mAb did not affect basal or Tim-1 ligation-induced TIGIT expression in B cells (Figure S5A), B cells from TIGIT-deficient (Tigit−/−) mice produced less IL-10 upon treatment with a number of stimuli, indicating that B cells may require TIGIT for optimal IL-10 production (Figure 4B). We then examined whether Tim-1+ B cells from Tigit−/− mice affect EAE development. As we reported previously, transfer of WT Tim- 1+ B cells significantly inhibited EAE severity (Xiao et al., 2015). Transfer of Tigit−/− Tim-1+ B cells also suppressed disease severity, but not as effectively as transfer of WT Tim-1+ B cells (Figure S5B), indicating that TIGIT is required for some of the regulatory activities of Tim-1+ B cells in suppressing inflammation. To further understand the role of TIGIT in B cells in vivo, we generated Tigitfl/fl mice (Figure S5C) and crossed them with CD19Cre/Cre mice to obtain mice lacking TIGIT specifically in B cells (CD19Cre/WTTigitfl/fl or TigitBKO). Efficient TIGIT deletion in B cells was confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure S5D). Up to 5 to 6 months of age, TigitBKO mice displayed a normal phenotype without any notable defects in Tim-1 expression in B cells or B cell development (Figures S5E and S5F). When immunized with MOG35–55, WT, CD19Cre/WT, and CD19Cre/WTTigitfl/WT showed comparable EAE development and severity. Compared to these control mice, young TigitBKO mice developed more severe EAE, with poorer recovery (Figure 4C), similar to Tim-1BKO mice (Figure 3A), indicating an important role of TIGIT in B cells in inhibiting CNS inflammation. Unlike Tim-1BKO mice, TigitBKO mice with age did not show clinical signs of dermatitis, weight loss, or rectal prolapse (Figure 4D). Interestingly, however, similar to Tim-1BKO mice, about 20% of TigitBKO mice developed spontaneous EAE-like paralytic disease (Figure 4D and Video S1). Histological examination of liver, lungs, kidneys, intestines, and CNS in aged TigitBKO mice revealed that 50% of the mice had lymphoid infiltrates in various organs/tissues, in contrast to 100% observed in Tim-1BKO mice (Figure 4D). Aged TigitBKO mice also had fewer and smaller foci of mononuclear cell infiltrates in livers, lungs, kidneys, and colons than Tim-1BKO mice (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Immunoregulatory Role of TIGIT in B Cells.

(A) Representative FACS plots showing Tim-1, TIGIT, and IL-10-GFP expression in splenic CD19+ B cells from 8-week-old IL10GFP tiger mice (n = 6) after cells were treated with anti-Tim-1 or control rIgG1 for three days.

(B) Splenic B cells from 8-week-old WT and Tigit−/− mice were treated with indicated stimuli for three days and IL-10 production in culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. *p < 0.01.

(C) 8-week-old mice were immunized with MOG35–55/CFA and scored daily for clinical EAE signs (n = 10 per group; *p < 0.05).

(D) Table and graph summarizing clinical and histological abnormalities in TigitBKO mice.

(E) Representative histological examination of indicated organs/tissues in TigitBKO and Tim-1BKO mice. Tim-1BKO mice showed marked lymphoid infiltrates in periportal areas of the liver, peribronchial areas, renal cortex, lamina propria, and submucosal areas of the large intestine. The extent of infiltration was much less in tissues of TigitBKO mice. No tissue inflammation was present in WT mice. Bar in the liver panel, 50 μm, applies to liver and kidney tissue panels; bar in the lung panels, 100 μm, applies to the lung tissue panels; bar in the intestine panel, 100 μm, applies to the intestine tissue panels.

(F) Phenotypes of brain-infiltrating immune cells determined by flow cytometry in WT (n = 9), TigitBKO (n = 4), and Tim-1BKO (n = 5) mice with spontaneous EAE-like paralysis. *p < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

See also Figures S4 and S5.

Additionally, the incidence of histopathological tissue inflammation in liver (33.3% versus 88.5%), lungs (33.3% versus 88.5%), intestines (44.4% versus 92.3%), and kidneys (5.6% versus 96.2%) of aged TigitBKO mice was much lower than that in aged Tim-1BKO mice (Figures 4D, 2A, and S5G), and inflammation was less wide-spread, as aged TigitBKO mice only had lymphoid infiltrates in two (22.2%) or three (22.2%) organs/tissues (Figure 4D), whereas 80.7% of aged Tim-1BKO mice had lymphoid infiltrates in four or five organs/tissues (Figure 2A). As aged TigitBKO and Tim-1BKO mice had a comparable incidence of spontaneous paralysis, we examined the brain infiltrates in the mice with paralysis and found that both strains with paralysis showed about a 4-fold increase of immune cell infiltrates brains, with increased T cells and especially CD11b+ myeloid cells, and a decreased frequency of Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 4F). Young TigitBKO mice, like young Tim-1BKO mice, showed no defect in Treg frequency, surface CTLA-4, CD39, and CD73 expression, or suppressive capacity, compared to control (Figures S5H–S5J).

Examination of peripheral immune compartments in aged TigitBKO mice demonstrated that those mice without organ/tissue inflammation had no obvious changes in immune cell infiltrates, compared to control mice. In contrast, T cells from spleens of aged TigitBKO mice with CNS infiltrates and paralysis were more activated and produced more IFN-g and IL-17. Also, levels of CD11b+ myeloid cells were increased, but there was no change in the frequency of Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure S5K).

Collectively, these data support that TIGIT, a checkpoint receptor differentially expressed on Tim-1+ B cells and induced by Tim-1 signaling, is not only critical for B cell-mediated suppression of inflammation, it is also required for B cell-mediated induction of tolerance, especially in the CNS.

DISCUSSION

Tim-1 is broadly expressed on multiple cell types and regulates multiple biological functions (Bonventre, 2014; Kuchroo et al., 2008; Rennert, 2011; Xiao et al., 2011). Here we have shown that over 80% of Tim-1BKO mice developed spontaneous multi- organ tissue inflammation as they age, clearly demonstrating that Tim-1 expression on B cells is required for maintaining self-tolerance. Surprisingly, 27% of the Tim-1BKO mice developed a spontaneous paralysis, indicating that the selective loss of Tim-1 on B cells is unique in protecting mice from the development of CNS inflammation, even without immunization with a CNS antigen or expression of a CNS antigen-specific TCR or BCR. This emphasizes that in addition to their critical regulatory role in maintaining self-tolerance systemically, Tim-1+ B cells have a unique role in maintaining tolerance in the CNS.

Although also targeting CD20 expressing CD8+ T cells (Sabatino et al., 2019), the efficacy of anti-CD20 therapy in multiple sclerosis has been mainly attributed to deletion of proinflammatory B cells and induction of “regulatory” B cells, as the immune system resets itself to replenish B cells in the repertoire (Li et al., 2016). Tim-1 is expressed in ~10% of B cells, yet Tim-1BKO mice developed both spontaneous and more severe induced CNS inflammation, supporting that Tim-1+ B cells may be critical in this context and that Tim-1 signaling is essential for regulating the balance between “regulatory” and proinflammatory B cells in order to maintain self-tolerance in tissues including the CNS.

Besides IL-10, Tim-1+ B cells also differentially express a panel of negative immune regulators, including a set of checkpoint receptors that likely contribute to the regulatory function of Tim-1+ B cells. In support of this, TIGITBKO mice, with age, preferentially develop spontaneous paralytic disease with CNS inflammation. It should be emphasized that development of spontaneous paralytic disease with CNS inflammation has not been observed previously in mice with global loss of negative regulatory molecules, including IL-10, CTLA-4, TIGIT, PD-1, or Tim-3. The checkpoint receptors not only induce CD8+ T cell exhaustion, but also enhance the regulatory function of Foxp3+ Tregs. As we have observed a similar set of checkpoint receptors expressed on Tim-1+ B cells that regulate tissue inflammation, this raises an interesting question of whether checkpoint blockade-induced anti-tumor immunity may also alter the regulatory function of B cells that express these checkpoint receptors.

Our data suggest that Tim-1+ B cells must limit inflammation through diverse regulatory mechanisms, and we speculate that individual regulatory mechanisms may be operational in a particular tissue and inflammatory setting. TIGIT appears to be preferentially required for Tim-1+ B cell-mediated self-tolerance in the CNS, and by analogy, there must be other regulatory mechanisms (preferentially or coordinately) responsible for Tim-1+ B cell-mediated self-tolerance in other organs and tissues. Alternatively, loss of individual effector mechanism in Tim-1+ B cells may only have a limited effect on the regulation of tissue inflammation, but multiple mechanisms may be coordinately working together in the B cells to regulate tissue inflammation in multiple organs or multiple tissue specificities.

A recent study has identified AhR as a critical transcription factor (TF) for the regulatory function of IL-10+ B cells by directly regulating IL-10 and suppressing proinflammatory gene expression (Piper et al., 2019). We also found that AhR is preferentially expressed and ranks at the top among TFs expressed in Tim-1+ B cells (Figure S4A). Maintenance and induction of AhR in these B cells require Tim-1 expression and signaling (Figure S4B). AhR is required for Tim-1-mediated expression of IL-10 and TIGIT by directly binding to their promoters in the B cells (Figures S4C–S4E). Importantly, AhR is required for the regulatory function of Tim-1+ B cells in ameliorating EAE severity (Figure S4F). It is possible that AhR in Tim-1+ B cells also regulates other regulatory mechanisms, besides IL-10 and TIGIT. In this regard, our computational analysis has identified putative AhR-binding sites in the promoter regions of other coinhibitory molecules such as Tim-3 and LAG3. Thus, it is very likely that AhR may serve as a critical TF responsible for the regulatory activity of Tim-1+ B cells by directly regulating the module of negative regulators and suppressing proinflammatory factors by binding to their promoters in these cells. In addition to AhR, our RNA-seq analysis has also identified a set of other TFs preferentially expressed in Tim-1+ B cells; however, whether any of these TFs is also required for Tim-1+ B cell regulatory function, needs further investigation.

In summary, we demonstrate that Tim-1+ B cells are essential in maintaining self-tolerance and restraining tissue inflammation, and that the Tim-1/TIGIT axis is required for their optimal regulatory function, especially for maintaining tolerance in the CNS. The regulatory function of Tim-1+ B cells has also been identified in infections and transplantation (Ding et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014; Mao et al., 2017). Thus, further understanding Tim-1+ B cells and their regulatory mechanisms would be valuable for treating immune-related diseases by selectively enhancing or inhibiting the B cell activity and/or their regulatory mechanisms.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Vijay K. Kuchroo. Email: vkuchroo@evergrande.hms.harvard.edu

Materials Availability

All unique/stable materials generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Material Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The accession number for the RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE150786

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

Tim-1 and Tigit floxed mice were generate on the C57BL/6 background. Targeting vectors containing genomic fragments of the Tim- 1 or Tigit gene were constructed by using C57BL/6 BAC clones. Linearized targeting vector was transfected into B6 embryonic stem (ES) cells. Homologous recombinants were identified by Southern-blot analysis, and were implanted into foster B6-albino mothers. Chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6 mice, and the F1 generation was screened for germline transmission. The Neo gene was removed by breeding F1 mice with a strain of actin promoter-driven Flipase transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory, 003800). C57BL/6 mice (000664), CD19Cre (006785), IL10GFP tiger (008379), AhRd (002921), muMT (002288), and Rag1−/− (002216) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Tim-1−/−, Tim-1Dmucin, and Tigit−/− mice, all on the C57BL/6 background, were described previously (Joller et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2015). Both females and males were used in the study. Ages of mice were indicated in figure legends. Mice were maintained and all animal experiments were done according to the animal protocol guidelines of Harvard Medical School.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell purification and cultures

For AC preparation, thymocytes from C57BL/6 mice were treated with 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich) for 8h. After an extensive wash, AC were used in cell cultures. Annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) staining was used to confirm apoptosis of thymocytes.

Splenic B cells were purified using MACS columns following staining with anti-mouse CD19 MACS beads. Cells were cultured in round-bottom 96-well plates in the presence of anti-Tim-1 (clone 5F12), AC, (Fab’)2 fragment anti-IgM, Anti-CD40, IL-21, or their combinations. After 3 days, IL-10 production in culture supernatants was measured by cytokine bead array (CBA) or ELISA. MACS purified CD19+ B cells were labeled with PE-anti-Tim-1 (RMT1–4) and then separated into Tim-1+ and Tim-1- B cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting for further uses.

CD4+CD62LhiCD25− naive CD4+ T cells were purified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting after a MACS bead isolation of CD4+ cells as previously described (Xiao et al., 2015). Naive CD4+ cells were activated with isolated CD19+ B cells plus soluble anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml). After 96 h, cells were collected for further experiments.

Single-cell suspensions from colon lamina propria tissue were prepared using the Lamina Propria Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated cells were resuspended in culture medium for further analysis. For isolation of CNS-infiltrating mononuclear cells, mice were first perfused through the left cardiac ventricle with cold PBS. The forebrain and cerebellum were dissected and spinal cords flushed out with PBS by hydrostatic pressure. CNS tissue was cut into pieces and digested with collagenase D (2.5 mg/ml, Roche Diagnostics) and DNase I (1 mg/ml, Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min. Mononuclear cells were isolated by passing the tissue through a 70 mm cell strainer, followed by a 70%/37% percoll gradient centrifugation. Mononuclear cells were removed from the interphase, washed, and resuspended in culture medium for further analysis.

For in vitro suppression assay, 5 × 104 FACS-sorted CD3e+ CD4+ CD25- conventional T cells (Tconv) from LNs and spleens of CD19Cre/WT mice were labeled with 5 μM CellTrace Violet and stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads(Dynabeads, Invitrogen) in presence of FACS sorted CD3e+ CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells from CD19Cre/WT, TIM-1BKO or TIGITBKO mice. Tconv proliferation was read out after 72h by flow cytometry and the division index of responder cells was analyzed using FlowJo based on the division of Cell Trace Violet. Suppression was then calculated with the formula % Suppression = (1-DivTreg/DivAlone) ×100% (DivTreg stands for the division index of responder cells with Tregs, and DivAlone stands for the division index of responder cells activated without Tregs).

Flow cytometry

For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated in culture medium containing phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (30 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), ionomycin (500 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), and GolgiStop (1 ml/ml, BD Biosciences) in a cell incubator with 10% CO2 at 37°C for 4 h. After surface markers were stained, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm and Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated cytokine antibodies at RT for 30 min before analysis. 7-AAD (BD Biosciences) was also included to gate out the dead cells. All data were collected on a FACSCalibur or an LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

EAE

Mice were immunized subcutaneously in the flanks with an emulsion containing MOG35–55 (80 mg/mouse) and M. tuberculosis H37Ra extract (3 mg/ml, Difco Laboratories) in CFA (100 μl/mouse). Pertussis toxin (100 ng/mouse, List Biological Laboratories) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0 and 2. Mice were monitored and assigned grades for clinical signs of EAE as previously described (Xiao et al., 2015). To evaluate the suppressive ability of Tim-1+ B cells, purified total B cells or Tim-1+ B cells were transferred i.v. into WT recipients. Hosts were then immunized to induce EAE.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

B cells from WT and AhRd mice were treated for 24 h with anti-Tim-1 or control rIgG1, fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min, and quenched with 0.125 M glycine. Chromatin was isolated and sheared to an average length of 300–500 bp by sonication. Genomic DNA (Input) was prepared by treating aliquots of chromatin with RNase, proteinase K and heated for de-crosslinking, followed by ethanol precipitation. AhR-bound DNA sequences were immuno-precipitated with an AhR-specific antibody (Biomol SA-210). Crosslinks were reversed by incubation overnight at 65 C, and ChIP DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) reactions were carried out in triplicate and experimental Ct values were converted to copy numbers detected by comparison with a DNA standard curve run on the same PCR plates. Copy number values were normalized for primer efficiency using the values obtained with input DNA and the same primer pairs.

RNA isolation, real-time PCR, and histology

RNA was extracted with RNeasy Plus kits (QIAGEN) and cDNA was made using iScript (BioRad). All of the real-time PCR probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Quantitative PCRs were performed using ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Tissues and organs from mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for > 12 h, processed, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned, and stained with H&E using standard procedures. Evaluations were made in a blinded fashion.

RNA-seq assay

Samples from isolated Tim-1- and Tim-1+ B cells were processed with the SMART-Seq2 protocol (Picelli et al., 2013), and sequenced on Illumina Hi-Seq 2500. The paired-end 38bp reads sequenced (26.53M ± 1.62M pairs of reads per sample) for each of the 8 sam- ples (4 Tim-1+ and 4 Tim-1- B cell samples derived from naive WT mice) were aligned to the mouse mm10 UCSC reference genome using Tophat version 2.0.10 (Kim et al., 2013) with default settings (read alignment rate of 82.81% ± 0.44% properly mapped pairs per sample). Gene expression levels were quantified for 22,815 genes in the mouse mm10 UCSC reference gene annotations using Cuff- quant in the Cufflinks suite version 2.2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2012). These levels were subsequently normalized across all 8 samples using Cuffnorm with default settings based on “geometric” normalization, which normalizes samples based on the median expression level in each sample, thus reporting normalized expression levels (FPKM: fragments per kilo bases of exons for per million mapped reads). Out of the 22,815 quantified reference genes, 15,519 genes were detected in at least one of the 8 samples at a normalized FPKM level > 0. Differential gene expression analysis comparing the 4 Tim-1+ and 4 Tim-1- B cell samples was performed by estimating the asymptotic t test (Student’s t-distribution) p values, False Discovery Rate (FDR) (Benjamini and Hochberg) values and fold-changes using the Comparative Marker Selection module in Gene Pattern (Reich et al., 2006). Significantly differentially expressed genes were identified using the asymptotic t test p value ≤ 0.05 and absolute fold change R ≥ selection criteria. Heatmaps visualizing the normalized gene expression levels (zero mean centering and unit standard deviation scaling of the expression levels for each gene, followed by saturating these normalized gene expression levels at +1 and −1) were generated using GENE-E/Morpheus.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The clinical score and incidence of EAE were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test (Figures 3A, 4C, S4F, and S5B), and comparisons for results (mean ± SEM) of BioLegend LEGEND plex (Figures 1D and 1E), ELISA (Figures 1C, 4B, and S4C), FACS (Figures 2C, 2E, 3B, 4F, S1C–S1F, S4D, S5D–S5F, and S5H–S5J), and real-time PCR (Figures 3F, S4B, and S4E) were analyzed by Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Significantly differentially expressed genes for RNA-seq analysis were identified using the asymptotic t test p value % 0.05 (Figures 3C–3E and S4A).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD19, Clone 6D5 | Biolegend | Cat# 115555; RRID: AB_2565970 |

| Anti-mouse B220, Clone RA3–6B | Biolegend | Cat# 103223; RRID: AB_313006 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b, Clone M1/70 | Biolegend | Cat# 101257; RRID: AB_2565431 |

| Anti-mouse CD3ε, Clone 145–2C11 | Biolegend | Cat# 100320; RRID: AB_312685 |

| Anti-mouse TCRβ, Clone H57–597 | Biolegend | Cat# 109230; RRID: AB_2562562 |

| Anti-mouse CD4, Clone RM4–5 | Biolegend | Cat# 100543; RRID: AB_10898318 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a, Clone 53–6.7 | Biolegend | Cat# 100744; RRID: AB_2562609 |

| Anti-mouse IFN-g, Clone XMG1.2 | Biolegend | Cat# 505813; RRID: AB_493312 |

| Anti-mouse IL-17A, Clone TC11–18H10.1 | Biolegend | Cat# 506904; RRID: AB_315464 |

| Anti-mouse IL10, Clone JES5–16E3 | Biolegend | Cat# 505008; RRID: AB_315362 |

| Anti-mouse TIGIT, Clone 1G9 | Biolegend | Cat# 142107; RRID: AB_2565648 |

| Anti-mouse CD62L, Clone MEL-14 | Biolegend | Cat:#104406; RRID: AB_313039 |

| Anti-mouse/human CD44, Clone IM7 | Biolegend | Cat# 103012; RRID: AB_312963 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c, Clone N418 | Biolegend | Cat# 117334; RRID: AB_2562415 |

| Anti-mouse TIM-1, Clone RMT1–4 | Biolegend | Cat# 119506; RRID: AB_2232887 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 | Biolegend | Cat# 103108; RRID: AB_312973 |

| Anti-mouse CD138, Clone 281–2 | Biolegend | Cat# 142506; RRID: AB_10962911 |

| Anti-mouse CD21, Clone CR2/CR1 | Biolegend | Cat# 123412; RRID: AB_2085160 |

| Anti-mouse CD23, Clone B3B4 | Biolegend | Cat# 101606; RRID: AB_312831 |

| Anti-mouse PD-1, Clone RMP1–30 | Biolegend | Cat:#109110; RRID: AB_572017 |

| Anti-mouse LAG-3, Clone C9B7W | Biolegend | Cat# 125212; RRID: AB_2561517 |

| Anti-mouse Tim-3, Clone 5D12 | Biolegend | Custom made |

| Anti-mouse TIM-1, Clone 5F12 | Xiao et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Anti-mouse CD93, Clone AA4.1 | eBioscience | Cat# 17–5892-82; RRID: AB_469466 |

| Anti-mouse FAS, Clone Jo2 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 557653; RRID: AB_396768 |

| Anti-mouse GL-7, Clone GL-7 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562080; RRID: AB_10894953 |

| AffiniPure Fab Fragment Goat Anti-Mouse IgM, μ chain specific | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 115–007-020; RRID: AB_2338477 |

| Anti-mouse AhR, Clone 4MEJJ | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12–5925-82; RRID: AB_2572644 |

| Anti-mouse FoxP3, Clone FJK-16 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 17–5773-82; RRID: AB_469457 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L4391 |

| Dexamethasone | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# D4902 |

| Phorbol-12-myristate-13 acetate (PMA) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# P8139 |

| Ionomycin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# I0634 |

| Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) | BD Difco | Cat# 263810 |

| M. tuberculosis H37 Ra, desiccated | BD Difco | Cat# 231141 |

| 7AAD | BD Biosciences | Cat# 559925 |

| Golgi Stop | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554724 |

| Fixable Viability w eFluor 506 | Invitrogen | Cat# 65–0866-14 |

| MOG35–55 peptide | Quality Controlled Biochemicals | N/A |

| Pertussis toxin | List Biological Laboratories | Cat# 180 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| LegendPlex (Mouse Th Cytokine Panel) | Biolegend | Cat# 740005 |

| BD Cytofix/Cytoperm | BD Biosciences | Cat# 51–2090KZ |

| BD Perm/Wash | BD Biosciences | Cat# 51–2091KZ |

| CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# C34557 |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Concentrate | Invitrogen | Cat# 00–5123-43 |

| Fixation/Perm Diluent | Invitrogen | Cat# 00–5223-56 |

| Permeabilization Buffer | Invitrogen | Cat# 00–8333-56 |

| RNeasy Plus Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 74134 |

| RNase-Free DNase Set | QIAGEN | Cat# 79254 |

| iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit | Bio-Rad | Cat# 1708891 |

| CD19 MicroBeads, mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130–052-201 |

| SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11756050 |

| TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4444557 |

| PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# KIT0204 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE150786 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Tim-1fl/fl mice | This paper | N/A |

| Tigitfl/fl mice | This paper | N/A |

| Tim-1BKO mice | This paper | N/A |

| TigitBKO mice | This paper | N/A |

| Tim-1−/− mice | Xiao et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Tim-1Δmucin mice | Xiao et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Tigit−/− mice | Joller et al., 2014 | N/A |

| C57BL/6 mice | Jackson laboratory | Cat# JAX:000664; RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| CD19Cre mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:006785; RRID: IMSR_JAX:006785 |

| Rag1−/− mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:002216; RRID: IMSR_JAX:002216 |

| B6.129P2-Igh-Jtm1Cgn/J mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 002438; RRID: IMSR_JAX:002438 |

| IL10GFP tiger mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:008379; RRID: IMSR_JAX:008379 |

| AhRd mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:002921; RRID: IMSR_JAX:002921 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlowJo v10.5.0 | FlowJo | https://ww.flowjo.com |

| Prism v7.0a and v8.1.2 | GraphPad | https://ww.graphpad.com |

| R | N/A | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| Other | ||

| anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads | Invitrogen | Cat# 11456D |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | DN25 |

| Collagenase D | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 11088882001 |

Highlights.

Tim-1+ B cells are required for maintaining immune tolerance

Tim-1 B cells differentially express TIGIT and other co-inhibitory molecules

B cell expression of TIGIT and many other regulators requires Tim-1 signaling

B cell TIGIT expression is preferentially required for maintaining CNS tolerance

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deneen Kozoriz for cell sorting and Dr. Mary Collins for advice and editing the paper. This work was supported by grants from the Lupus Research Alliance (332938 to S.X.), the National MS Society (RG-1907–34686), and the National Institutes of Health (P01AI039671, P01AI045757, P01073748, and 1P01AI129880 to V.K.K.). N.J. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP00P3_150663) and the European Research Council (677200). V.K.K is the Dr. William E. Paul Distinguished Innovator Award recipient from the Lupus Research Alliance.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

S.X. is the employee of Celsius Therapeutics. V.K.K. has an ownership interest and is a member of the SAB for Celsius Therapeutics and Tizona Therapeutics. V.K.K.’s interests were reviewed and managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners Healthcare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. A provisional patent application was filed including work of this paper.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107892.

REFERENCES

- Anderson AC, Joller N, and Kuchroo VK (2016). Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity 44, 989–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravena O, Ferrier A, Menon M, Mauri C, Aguillón JC, Soto L, and Catalán D. (2017). TIM-1 defines a human regulatory B cell population that is altered in frequency and function in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Res. Ther 19, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre JV (2014). Kidney injury molecule-1: a translational journey. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc 125, 293–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Yeung M, Camirand G, Zeng Q, Akiba H, Yagita H, Chalasani G, Sayegh MH, Najafian N, and Rothstein DM (2011). Regulatory B cells are identified by expression of TIM-1 and can be induced through TIM-1 ligation to promote tolerance in mice. J. Clin. Invest 121, 3645–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu XL, He H, Lin L, Luo GX, Wen YF, Xiang DC, and Qiu J. (2017). Tim-1+ B cells suppress T cell interferon-gamma production and promote Foxp3 expression, but have impaired regulatory function in coronary artery disease. APMIS 125, 872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joller N, Peters A, Anderson AC, and Kuchroo VK (2012). Immune checkpoints in central nervous system autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev 248, 122–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joller N, Lozano E, Burkett PR, Patel B, Xiao S, Zhu C, Xia J, Tan TG, Sefik E, Yajnik V, et al. (2014). Treg cells expressing the coinhibitory molecule TIGIT selectively inhibit proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell responses. Immunity 40, 569–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, and Salzberg SL (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen B, Hegedüs L, Lundy SK, Brimnes MK, Smith TJ, and Nielsen CH (2015). Characterization of regulatory B cells in Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. PLoS ONE 10, e0127949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchroo VK, Dardalhon V, Xiao S, and Anderson AC (2008). New roles for TIM family members in immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 8, 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC, and Petrovas C. (2014). Coinhibitory receptors and CD8 T cell exhaustion in chronic infections. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 9, 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Rezk A, Healy LM, Muirhead G, Prat A, Gommerman JL, and Bar-Or A; MSSRF Canadian B Cells in MS Team (2016). Cytokine-defined B cell responses as therapeutic targets in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol 6, 626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhan W, Kim CJ, Clayton K, Zhao H, Lee E, Cao JC, Ziegler B, Gregor A, Yue FY, et al. (2014). IL-10-producing B cells are induced early in HIV-1 infection and suppress HIV-1-specific T cell responses. PLoS ONE 9, e89236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Liu B, Jiang Z, and Jiang Y. (2014). Reduced numbers of regulatory B cells are negatively correlated with disease activity in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol 33, 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan R, Demircik F, Surianarayanan S, Allen JL, Divanovic S, Trompette A, Yogev N, Gu Y, Khodoun M, Hildeman D, et al. (2009). Nonredundant roles for B cell-derived IL-10 in immune counter-regulation. J. Immunol 183, 2312–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann MK, Maresz K, Shriver LP, Tan Y, and Dittel BN (2007). B cell regulation of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells and IL-10 via B7 is essential for recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol 178, 3447–3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H, Pan F, Wu Z, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhang P, Gou M, and Dai G. (2017). Colorectal tumors are enriched with regulatory plasmablasts with capacity in suppressing T cell inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol 49, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri C, and Menon M. (2015). The expanding family of regulatory B cells. Int. Immunol 27, 479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picelli S, Björklund AK, Faridani OR, Sagasser S, Winberg G, and Sandberg R. (2013). Smart-seq2 for sensitive full-length transcriptome profiling in single cells. Nat. Methods 10, 1096–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper CJM, Rosser EC, Oleinika K, Nistala K, Krausgruber T, Rendeiro AF, Banos A, Drozdov I, Villa M, Thomson S, et al. (2019). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor contributes to the transcriptional program of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells. Cell Rep. 29, 1878–1892 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M, Liefeld T, Gould J, Lerner J, Tamayo P, and Mesirov JP (2006). GenePattern 2.0. Nat. Genet 38, 500–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert PD (2011). Novel roles for TIM-1 in immunity and infection. Immunol. Lett 141, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert RC, Roes J, and Rajewsky K. (1997). B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1317–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino JJ Jr., Wilson MR, Calabresi PA, Hauser SL, Schneck JP, and Zamvil SS (2019). Anti-CD20 therapy depletes activated myelin-specific CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25800–25807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wang J, Pefanis E, Chao J, Rothschild G, Tachibana I, Chen JK, Ivanov II, Rabadan R, Takeda Y, and Basu U. (2015). Transcriptomics identify CD9 as a marker of murine IL-10-competent regulatory B cells. Cell Rep. 13, 1110–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, and Pachter L. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc 7, 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Zhu B, Jin H, Zhu C, Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH, and Kuchroo VK (2011). Tim-1 stimulation of dendritic cells regulates the balance between effector and regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol 41, 1539–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Brooks CR, Zhu C, Wu C, Sweere JM, Petecka S, Yeste A, Quintana FJ, Ichimura T, Sobel RA, et al. (2012). Defect in regulatory B-cell function and development of systemic autoimmunity in T-cell Ig mucin 1 (Tim-1) mucin domain-mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12105–12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Brooks CR, Sobel RA, and Kuchroo VK (2015). Tim-1 is essential for induction and maintenance of IL-10 in regulatory B cells and their regulation of tissue inflammation. J. Immunol 194, 1602–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung MY, Ding Q, Brooks CR, Xiao S, Workman CJ, Vignali DA, Ueno T, Padera RF, Kuchroo VK, Najafian N, and Rothstein DM (2015). TIM-1 signaling is required for maintenance and induction of regulatory B cells. Am. J. Transplant 15, 942–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for the RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE150786