Abstract

Objective

To examine the influences of depression and anxiety on headache‐related disability in people with episodic migraine or chronic migraine.

Background

Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities in people with migraine, especially among those with chronic migraine.

Methods

This cross‐sectional analysis of data from the longitudinal, internet‐based Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study assessed sociodemographic and headache features, and headache‐related disability (Migraine Disability Assessment Scale). Four groups were defined based on scores from validated screeners for depression (9‐item Patient Health Questionnaire) and anxiety (7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale): depression alone, anxiety alone, both, or neither.

Results

Respondents (N = 16,788) were predominantly women (74.4% [12,494/16,788]) and white (84.0% [14,044/16,788]); mean age was 41 years. Depression was more likely in persons with chronic migraine vs episodic migraine (56.6% [836/1476] vs 30.0% [4589/15,312]; P < .001), as were anxiety (48.4% [715/1476] vs 28.1% 4307/15,312]; P < .001) and coexisting depression and anxiety (42.0% [620/1476] vs 20.8% [3192/15,312]; P < .001). After controlling for headache frequency and other covariates, depression alone, and anxiety alone were associated with 56.0% (rate ratio [RR], 1.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.46‐1.66) and 39.0% (RR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.30‐1.50) increased risks of moderate/severe migraine‐related disability (both P < .001), respectively; the combination had an even greater effect on risk of moderate/severe disability (79.0% increase; RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.71‐1.87; P < .001).

Conclusions

Depression alone and anxiety alone are associated with greater headache‐related disability after controlling for sociodemographic and headache features. Coexisting depression and anxiety are more strongly associated with disability than either comorbidity in isolation. Interventions targeting depression and anxiety as well as migraine itself may improve headache‐related disability in people with migraine.

Keywords: migraine, depression, anxiety, headache‐related disability, comorbidity

Abbreviations

- AMPP

American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ASC‐12

12‐item Allodynia Symptom Checklist

- BMI

body mass index

- CaMEO

Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes

- CM

chronic migraine

- DSM‐IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

- EM

episodic migraine

- GAD‐7

7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale

- ICHD‐3

International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment Scale

- MSSS

Migraine Symptom Severity Score

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- RR

rate ratio

Introduction

Migraine, a chronic and debilitating neurologic disease, is characterized by episodic attacks of headache pain and other associated symptoms. 1 , 2 Globally, migraine affects approximately 1 in 7 individuals with a prevalence of more than 1 billion people. It is second only to lower back pain as a leading cause of years lived with disability. 3

Depression and anxiety are comorbid with migraine and with each other. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Although estimates vary, in population‐based samples of people with migraine, up to 47% have comorbid depression, and up to 58% have comorbid anxiety. 7 , 9 Both depression and anxiety are more common among people with chronic migraine (CM; defined as at least 15 headache days per month over the preceding 3 months with migraine features present on at least 8 days per month) than in people with episodic migraine (EM). 9 , 10 , 11 Furthermore, the presence of comorbid depression in people with EM has been shown to predict risk of progression to CM the following year. 12 Relationships between comorbid depression and migraine are bidirectional. 4 , 7 , 9 , 13 This is consistent with emerging evidence of genetic links between migraine, depression, and anxiety. 14

In general, the presence of both migraine and psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression portends worsened symptomatology for each condition. 5 , 12 Comorbid depression and anxiety in people with migraine are associated with greater health expenditures and medication use than in people with migraine without these comorbidities. 9 , 15 Psychiatric comorbidities in migraine can diminish quality of life (QoL) and increase the burden and disability associated with migraine. 16 , 17 , 18 Comorbid depression and/or anxiety can also affect medication selection, response to preventive medication, behavioral migraine treatment, and adherence to migraine treatment plans. 9 , 19 , 20

The separate and joint associations of depression and anxiety with disability in persons with migraine have not been evaluated; further, analyses of relationships between depression and anxiety and migraine disability have typically not been adjusted for headache days. The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study was designed to characterize self‐reported headache symptoms, severity, disability, comorbidities, and other variables in a representative U.S. sample of people with migraine. 21 This subanalysis of the CaMEO Study sample was undertaken to investigate and compare the separate and joint influences of depression and anxiety on headache‐related disability in people with migraine, to compare these effects in CM and EM, to identify unmet needs, and to provide relevant clinical information to guide treatment planning. We hypothesized that at increasing levels of monthly headache‐day frequency, persons with depression or anxiety would have elevated levels of headache‐related disability and that the effects would be greater in persons with coexisting depression and anxiety.

Methods

Study Design

The CaMEO Study methodology has been detailed previously. 21 This longitudinal Internet‐based study with cross‐sectional modules (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01648530) assessed headache symptoms, severity, frequency, and disability; and migraine‐related consulting practices, health‐care utilization, medication use, comorbid health conditions, and family related burden associated with headache over the course of 1 year. 21 Recruiting and screening occurred between September and October 2012. Participants were recruited from an Internet research panel (Dynata [formerly Research Now], Plano, TX, USA) using sampling quotas based on the U.S. Census. The CaMEO Study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was not required for survey respondents; completion of the survey was considered consent to participate. All study authors had full access to all data.

Study Participants

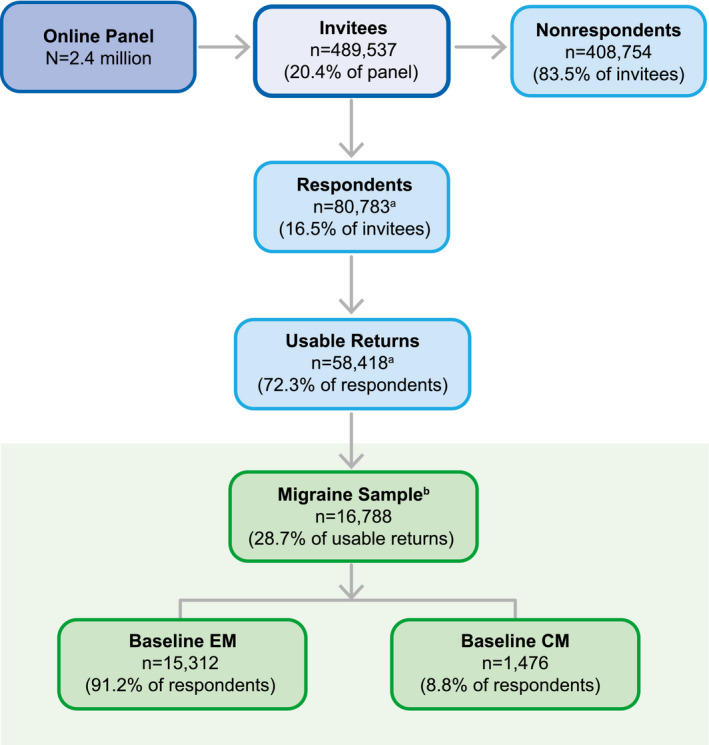

Adults were eligible for inclusion in the study if they volunteered to participate (Fig. 1), 22 passed quality control measures, and met modified symptom criteria for migraine from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD‐3) using the validated American Migraine Study/American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study migraine screener. 21 , 23 Respondents with CM were defined as those with at least 15 headache days per month (Silberstein‐Lipton criteria 24 ), calculated as the average of monthly headache days over the preceding 3 months. 21

Fig 1.

Respondent flow diagram. About 22,365 respondents abandoned the survey, were over quota, or had invalid (unusable) data and were removed during data cleaning. Met inclusion criteria: agreed to participate, screened positive for modified International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition, migraine criteria, were ≥18 years of age, and had ≥1 headache in the previous 12 months. Note: There was 1 person with missing data for the anxiety and depression measures, so the sample size for this study differs by n = 1 from the total CaMEO baseline sample. Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO); Chronic Migraine (CM); episodic migraine (EM).

Headache‐Related Disability

The Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) is a 7‐item measure of headache‐related disability over the previous 3 months. 25 The 5 scored items assess the number of days that migraine prevented (absenteeism) or limited (presenteeism) work and nonwork activities. The total score sums the number of days for these 5 items, with higher scores indicating greater disability classified into 4 severity grades: 0 to 5: Grade I (minimal or infrequent disability); 6 to 10: Grade II (mild or infrequent disability); 11 to 20: Grade III (moderate disability); and ≥21: Grade IV (severe disability).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the 9‐item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9), 26 a validated measure of major depressive disorder based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM‐IV) criteria. 27 This assessment tool sums 9 questions rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) to provide a total possible score of 27 to determine depression over the preceding 2 weeks. The validated sum scoring method advised that PHQ‐9 total scores can be used to categorize depression as none to minimal (0‐4), mild (5‐9), moderate (10‐14), moderately severe (15‐19), and severe (20‐27). 26 For this analysis, respondents with a PHQ‐9 total score ≥10 were classified as screening positive for depression.

Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using the 7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD‐7). This validated scale sums 7 questions based on DSM‐IV criteria 27 rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) for the preceding 2 weeks, resulting in a total score between 0 and 21. The validated scoring method advised that GAD‐7 scores of 10 to 14 indicate moderate anxiety, and scores ≥15 indicate severe anxiety. 28 For this analysis, respondents with a GAD‐7 total score ≥10 were classified as screening positive for anxiety.

Combined Anxiety/Depression Variable

Four psychiatric subgroups of participants were defined based on the presence and/or absence of depression and anxiety using responses to screeners for symptoms of depression (PHQ‐9 score ≥10) and anxiety (GAD‐7 score ≥10) as follows: Neither depression nor anxiety, depression alone, anxiety alone, and both depression and anxiety.

Other Assessments

The influences of depression and anxiety were assessed both separately and jointly on the following factors: sociodemographic and headache features, migraine symptom severity composite sum score (Migraine Symptom Severity Score [MSSS]), and cutaneous allodynia (based on the 12‐item Allodynia Symptom Checklist [ASC‐12]). The MSSS, a composite index, is based on the frequency of 7 key migraine features, including unilateral pain, pulsatile pain, moderate or severe pain intensity, routine activities worsening pain, nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia. 29 Responses for each feature range from 1 to 4 (lower to higher frequency), yielding an overall sum score of 7 to 28. For the ASC‐12 (scoring range: 0 = not applicable/never/rarely; 1 = less than half the time; 2 = half the time or more), scores of at least 3 are indicative of the presence of allodynia. 30

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are provided for the total sample, comparing episodic and chronic migraine groups and across the 4 anxiety/depression symptom groups. Ratio scale variables (age, body mass index [BMI], monthly headache days) and interval scale variable (MSSS) are described by means and standard deviations. Nominal scale variables (gender, race) and ordinal scale variables (depression, anxiety, allodynia, MIDAS grade III or IV, income, monthly headache day categories) are described by percentages.

T‐test for independent groups (for EM vs CM comparisons) and one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA; for comparisons across the 4 psychiatric subgroups) were used to test for differences across interval or ratio scale variables, and chi‐squared was used to test differences for nominal or ordinal scale variables. All tests were 2 sided with a significance level set at .05.

MIDAS was modeled using negative binomial regression, which was applied to account for the skewed count distribution of MIDAS scores. The 4‐group anxiety and depression variable was the primary independent variable of interest. Additional covariates included age, gender, income, race, allodynia, BMI, monthly headache‐day frequency, and MSSS. Results were reported as rate ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs. The adjusted negative binomial regression model also was programed to generate predicted MIDAS scores, which were then used in a plot against monthly headache‐day frequency. All analyses were undertaken using SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Study Respondent Demographics and Disposition

Full details of the study respondents have been published previously. 21 The sociodemographic characteristics of the 16,788 respondents with migraine who qualified for inclusion are provided for the entire population in Table 1 and for the entire population stratified by the presence or absence of depression or anxiety in Table 2. There was 1 respondent with missing data on the depression and anxiety measures; therefore, this study sample differs by n = 1 from the total CaMEO baseline sample. Respondents were predominantly women (74.4%) and white (84.0%) with a mean BMI of 28.7 kg/m2 (overweight). At baseline, respondents had a mean monthly headache‐day frequency of 5.0 and mean MSSS score of 22.4. Among all respondents, 6539 (39.0%) had Grade III/IV (moderate to severe) MIDAS scores, and 5820 (45.4%) had cutaneous allodynia (ASC‐12 ≥3; Table 1). There were significant differences across the anxiety and depression subgroups in all of the sociodemographic characteristics evaluated, except race (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics, Headache Characteristics, and Depression† and/or Anxiety‡ for All Respondents with Migraine

| Characteristic | Respondents (N = 16,788)§ |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 41 (14) |

| Women, n (%) | 12,494 (74.4) |

| Race,¶ n (%) | |

| White | 13,562 (81.1) |

| Black | 1540 (9.2) |

| Other | 1106 (6.6) |

| Multiracial | 518 (3.1) |

| Annual household income,¶ n (%) | |

| <$30,000 | 3741 (22.5) |

| $30,000‐$49,999 | 2990 (17.9) |

| $50,000‐$74,999 | 3774 (22.6) |

| ≥$75,000 | 6158 (37.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.7 (7.6) |

| Cutaneous allodynia, ASC‐12 ≥3,¶ n (%) | 5820 (45.4) |

| MSSS, mean (SD) | 22.4 (3.2) |

| MIDAS score grade III/IV, n (%) | 6539 (39.0) |

| Monthly headache‐day frequency | |

| Days/month, mean (SD) | 5.0 (6.0) |

| Category, n (%) | |

| 0‐4 days/month | 11,159 (66.5) |

| 5‐9 days/month | 2904 (17.3) |

| 10‐14 days/month | 1249 (7.4) |

| ≥15 days/month | 1476 (8.8) |

| Depression† | 5425 (32.3) |

| Anxiety‡ | 5022 (29.9) |

| Psychiatric subgroups, n (%) | |

| Depression only | 1613 (9.6) |

| Anxiety only | 1210 (7.2) |

| Depression and anxiety | 3812 (22.7) |

| Neither depression nor anxiety | 10,153 (60.5) |

Depression was defined as 9‐item Patient Health Questionnaire score ≥10.

Anxiety was defined as 7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale score ≥10.

Subsample that completed Endophenotype Module and who were included in the final model. Note: There was one person with missing data for the anxiety and depression measures, so the sample size for this study differs by n = 1 from the total CaMEO baseline sample.

Results were not provided by all respondents; percentages are reported as the percentage of respondents for each data point.

ASC‐12 = 12‐item Allodynia Symptom Checklist; BMI = body mass index; CM = chronic migraine; EM = episodic migraine; MIDAS = Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; MSSS = Migraine Symptom Severity Score.

Table 2.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics by Comorbidity Group among Persons with Migraine

| Parameter | Variable† | Anxiety Only, 1210 (7.2) | Depression Only, 1613 (9.6) | Both Anxiety and Depression, 3812 (22.7) | No Anxiety, No Depression, 10,153 (60.4) | Chi/F | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 210 (17.4) | 449 (27.8) | 893 (23.4) | 2742 (27) | 67.462 | <.001 |

| Female | 1000 (82.6) | 1164 (72.2) | 2919 (76.6) | 7411 (73) | — | — | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 39 (13) | 40 (14) | 38 (13) | 43 (15) | F = 135.714 | <.001 |

| Race | White | 978 (80.9) | 1284 (80.0) | 2998 (79.2) | 8302 (82.0) | 24.995 | .003 |

| Black | 119 (9.8) | 155 (9.7) | 363 (9.6) | 903 (8.9) | — | — | |

| Other | 70 (5.8) | 109 (6.8) | 281 (7.4) | 646 (6.4) | — | — | |

| Multiracial | 42 (3.5) | 58 (3.6) | 145 (3.8) | 273 (2.7) | — | — | |

| Income category | <$30,000 | 265 (22.0) | 423 (26.3) | 1261 (33.2) | 1792 (17.8) | 567.459 | <.001 |

| $30,000‐$49,999 | 221 (18.3) | 337 (20.9) | 782 (20.6) | 1650 (16.4) | — | — | |

| $50,000‐$74,999 | 296 (24.5) | 374 (23.2) | 736 (19.4) | 2368 (23.6) | — | — | |

| ≥$75,000 | 424 (35.2) | 475 (29.5) | 1018 (26.8) | 4241 (42.2) | — | — | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | Mean (SD) | 28.0 (7.54) | 30.5 (8.38) | 29.7 (8.59) | 28.1 (6.99) | F = 74.002 | <.001 |

| Allodynia‡ | No | 427 (47.3) | 573 (47.0) | 1123 (39.5) | 4867 (62.1) | 486.274 | <.001 |

| Yes | 476 (52.7) | 646 (53.0) | 1722 (60.5) | 2976 (37.9) | — | — | |

| Monthly HA days | Mean (SD) | 5.0 (5.6) | 6.4 (7.0) | 7.3 (7.4) | 4.0 (5.0) | F = 336.779 | <.001 |

| MSSS | Mean (SD) | 22.7 (3.1) | 22.6 (3.1) | 23.3 (3.1) | 22.0 (3.2) | F = 150.033 | <.001 |

Values are n (%) unless noted otherwise.

Allodynia among n = 12,810 respondents from the Endophenotype Module.

BMI = body mass index; HA = headache; MSSS = Migraine Symptom Severity Score.

Depression criteria were met by 5425 (32.3%) respondents. Anxiety criteria were met by 5022 (29.9%) respondents. Of all respondents, 1613 (9.6%) had depression only, 1210 (7.2%) had anxiety only, and 3812 (22.7%) had both depression and anxiety; 10,153 (60.5%) respondents had neither depression nor anxiety (Table 1).

Headache Characteristics: EM vs CM

There were 15,312 (91.2%) respondents characterized as having EM and 1476 (8.8%) characterized as having CM. By definition, respondents with CM had a greater number of headache days per month than did those with EM (21.0 vs 3.5 days/month, P < .001; Table 3). Respondents with CM compared with EM, respectively, were also more likely to have cutaneous allodynia (ASC‐12 ≥3, 697 [62.7%] vs 5123 [43.8%]; P < .001), to experience significantly greater headache‐related disability (MIDAS Grade III/IV, 1187 [80.4%] vs 5352 [35.0%]; P < .001), and to have a higher mean symptom severity as assessed by the MSSS (23.8 vs 22.2; P < .01; Table 3).

Table 3.

Headache and Psychiatric Comorbidity Characteristics at Baseline by EM and CM

| Characteristic | EM (n = 15,312) | CM (n = 1476) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous allodynia, ASC‐12 ≥3,† n (%) | 5123 (43.8) | 697 (62.7) | <.001 |

| MSSS, mean (SD) | 22.2 (3.2) | 23.8 (3.0) | <.01 |

| MIDAS score grade III/IV, n (%) | 5352 (35.0) | 1187 (80.4) | <.001 |

| Monthly headache‐day frequency | |||

| Days/month, mean (SD) | 3.5 (3.2) | 21.0 (4.9) | <.001 |

| Category, n (%) | |||

| 0‐4 days/month | 11,159 (72.9) | 0 | <.001 |

| 5‐9 days/month | 2904 (19.0) | 0 | |

| 10‐14 days/month | 1249 (8.2) | 0 | |

| ≥15 days/month | 0 | 1476 (100) | |

| Depression‡ | 4589 (30.0) | 836 (56.6) | <.001 |

| Anxiety§ | 4307 (28.1) | 715 (48.4) | <.001 |

| Psychiatric subgroups | <.001 | ||

| Depression only | 1397 (9.1) | 216 (14.6) | |

| Anxiety only | 1115 (7.3) | 95 (6.4) | |

| Depression and anxiety | 3192 (20.8) | 620 (42.0) | |

| Neither depression nor anxiety | 9608 (62.7) | 545 (36.9) |

Results were not available for all respondents; percentages are reported as the percentage of respondents for each data point.

Depression was defined as 9‐item Patient Health Questionnaire score ≥10.

Anxiety was defined as 7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale score ≥10.

ASC‐12 = 12‐item Allodynia Symptom Checklist; CM = chronic migraine; EM = episodic migraine; MIDAS = Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; MSSS = Migraine Symptom Severity Score.

Depression and Anxiety Status: EM vs CM

Clinically relevant levels of depression, defined by a PHQ‐9 score ≥10, were more likely to be present in respondents with CM than EM (n = 836 [56.6%] vs n = 4589 [30.0%]; P < .001). Clinically relevant levels of anxiety, defined by a GAD‐7 score ≥10, were more likely to be present in respondents with CM than EM (n = 715 [48.4%] vs n = 4307 [28.1%]; P < .001). Respondents with CM compared with EM were more likely to have met criteria for depression only (n = 216 [14.6%] vs n = 1397 [9.1%]) or for depression and anxiety (n = 620 [42.0%] vs n = 3192 [20.8%]), and respondents with EM compared with CM were more likely to have met criteria for anxiety only (n = 1115 [7.3%] vs n = 95 [6.4%]) or having neither depression nor anxiety (n = 9608 [62.7%] vs n = 545 [36.9%]; P < .001; Table 3).

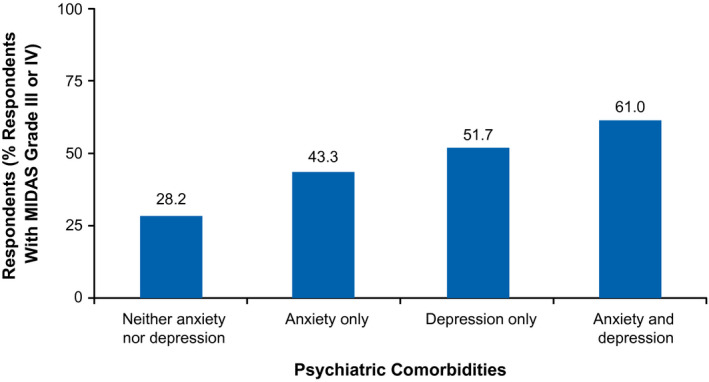

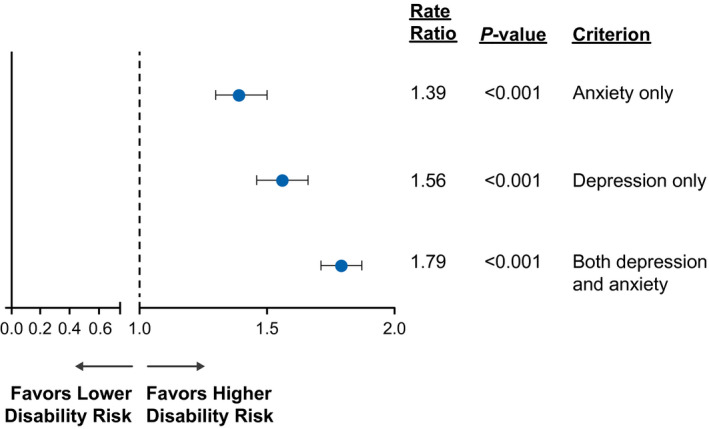

Relationship of MIDAS Score With Psychiatric Comorbidities

MIDAS scores increased in the presence of the assessed psychiatric comorbidities (Fig. 2). The proportion of respondents with a Grade III/IV MIDAS score reflecting moderate/severe disability among respondents with neither depression nor anxiety was 28.2%. Rates of moderate/severe disability were higher among respondents with anxiety alone (43.3%), depression alone (51.7%), and those with both depression and anxiety (61.0%). A range of factors was associated with the MIDAS scores in the moderate or severe disability range (Fig. 3), including monthly headache‐day frequency, MSSS, cutaneous allodynia, depression alone, anxiety alone, and both depression and anxiety. After controlling for headache‐day frequency and other covariates, depression alone, and anxiety alone increased the risk of disability caused by migraine by 56.0% (RR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.46,1.66; P < .001) and 39% (RR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.30,1.50; P < .001), respectively, and together had an even greater effect (79.0% increase in risk; RR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.71,1.87; P < .001; Fig. 3). Increasing age, being male, and being white were all protective against increases in MIDAS, as evidenced by RRs <1 with all covariates included in the model (Table S1 in Supplemental Data).

Fig 2.

Percentage of respondents with moderate or severe disability as indicated by a Migraine Disability Assessment Scale Grade of III or IV, stratified by presence of anxiety and/or depression. Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS).

Fig 3.

Predictors of headache‐related disability (MIDAS), as indicated by RRs and P values. The model was run adjusting for sex, age (in 10‐year increments), race (white vs nonwhite), BMI, annual household income, monthly headache‐day frequency, MSSS score (1‐point increments), and cutaneous allodynia. Sex, age in 10‐year increments, white race, BMI, monthly headache‐day frequency, MSSS score (1‐point increments), and cutaneous allodynia were all significant. Income brackets were also included in the model and were significant for $50,000 to $74,999 and ≥$75,000. The reference group had neither anxiety nor depression. Body mass index (BMI); Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS); Migraine Symptom Severity Score (MSSS); rate ratio (RR).

Relationship of MIDAS Score With Headache‐Day Frequency

Predicted MIDAS scores by monthly headache‐day frequency ranged from 5 to 60 for those with 0 to 14 headache days per month, and from 27 to 282 for those with 15 to 30 headache days per month. Among the psychiatric symptom subgroups, the greatest risk of headache‐related disability at nearly any given headache‐day frequency was observed among respondents with both depression and anxiety, while the lowest risk of disability was observed for those with neither condition (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Predicted MIDAS score by monthly headache days for each psychiatric subgroup. Note that for 0‐14 monthly headache days, the predicted mean MIDAS scores on the Y‐axis range from 0 to 60, whereas for 15‐30 monthly headache days, they range from 0 to 300. Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDASs).

Discussion

Prior research has demonstrated robust associations among depression, anxiety, and migraine. 6 , 18 , 31 The present analysis expands on the existing literature by demonstrating that depression and anxiety are separately and jointly associated with headache‐related disability in persons with migraine. Using validated clinical cutoffs on the PHQ‐9 and GAD‐7 scales, this subanalysis of the CaMEO study population revealed that clinically relevant depression and anxiety were present in a large proportion of respondents with migraine. In agreement with prior studies, a significantly larger proportion of respondents with CM than EM reported clinically relevant depression and anxiety. 11 , 32 , 33 , 34

In our study, the presence of clinically relevant depression and anxiety individually was significantly associated with moderate/severe headache‐related disability as measured by MIDAS. Depression and anxiety together showed a higher association with disability than either depression alone or anxiety alone. The lower bound of the 95% CI for the rate of moderate/severe disability in the group with depression and anxiety exceeded the upper bound of the 95% CI for the group with either depression alone or anxiety alone. These results support a combined influence of depression and anxiety on headache‐related disability. Comorbid conditions in general have been shown to explain a large proportion of the disability associated with migraine. 35 A nationally representative, face‐to‐face household survey of 5692 U.S. adults showed that 83% of participants with migraine had some form of comorbidity (eg, mental disorders [53%], chronic pain disorders [58%], and physical diseases [47%]). 35 Results of the study showed that after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid conditions explained approximately 65% of role disability (days with impaired role functioning per the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule) associated with migraine. 35 The individual contributions of anxiety and depression to migraine and, further, to headache‐related disability remain to be fully understood.

Prior literature is broadly compatible with our findings, although there are some discrepancies. Most studies have demonstrated migraine's association with both depression and anxiety, albeit with some variations in rates. 6 , 7 , 10 , 16 In contrast to findings that depressive symptoms are more common than anxiety symptoms, other studies have found that anxiety is more common than depression in people with migraine. 7 , 36 The FRAMIG 3 Study, a nationwide population‐based postal survey carried out in France (n = 1179 respondents with migraine), used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to assess anxiety and depression and reported that 28% of respondents with migraine had anxiety alone, 3% had depression alone, and 19% had both anxiety and depression. 7 The lower rate of anxiety vs depressive symptoms in our analysis may be attributed to our use of the GAD‐7, which assesses symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder but not other anxiety disorders such as panic disorder. Thus, we may have underestimated the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the CaMEO population. The AMPP Study 10 and the CaMEO Study used similar approaches to defining migraine and assessing depression and anxiety, yet, the rates of depression and anxiety were lower in the AMPP Study population compared with the present report. 10 About 30% of respondents with CM were categorized as having depression (PHQ‐9 score ≥10) in the AMPP Study compared with 57% in the current analysis. In the AMPP Study, about 30% had a self‐reported physician diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, whereas in this sample 48% were classified as positive for clinically relevant anxiety symptoms (GAD‐7 total score ≥10). The AMPP Study had a higher participation rate than the CaMEO Study (65% vs 17%), and AMPP Study data were collected by mailed questionnaire in contrast with the Web survey used in the CAMEO Study. 37 Perhaps these differences in populations and methodologies account for between‐study differences.

In addition to the well‐described comorbidity of migraine, anxiety, and depression, previous studies have provided further evidence that comorbid depression and/or anxiety significantly negatively influence QoL and increase the burden of migraine. 16 , 17 For example, in a small population of Korean patients with migraine, depression, and anxiety together were associated with a significant increase in headache frequency in comparison to patients with migraine without either comorbidity alone. 38 In that same population, anxiety alone and anxiety plus depression were associated with more intense headache pain than was the absence of these comorbidities. 38

People with migraine and comorbid anxiety and/or depression respond differently to acute and preventive migraine treatments than do those without anxiety or depression. The FRAMIG 3 Study observed that perceived efficacy of and satisfaction with acute treatment of migraine were lower in people with anxiety alone or depression and anxiety together than in those with neither depression nor anxiety, indicating that acute treatment may be suboptimal in this subset of the migraine population. 7 In contrast, people with migraine and depression and/or anxiety may respond better to preventive treatment than those without either comorbidity. An analysis of data from the Treatment of Severe Migraine trial (n = 177), reported greater reductions in migraine days and migraine‐related disability with preventive treatment in participants with a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis compared with those who had neither diagnosis. 19

Total annual health‐care expenses for patients with migraine and depression were found to be higher compared with costs for patients with migraine without comorbid depression ($10,012 vs $4740; P < .001). 15 In addition, patients with comorbid depression were more likely to use migraine prophylactic medication than patients with migraine alone (50.6% vs 37.3%, P < .001) and were also more likely to use health services (doctor visits, prescriptions, emergency department visits, or hospital admissions) for any cause than were those with migraine alone. It is not possible to determine causation from these relationships, which may be influenced by biases such as Berkson's bias. The results of our study and previous studies support a need for further investigations of the effect of depression and anxiety on migraine‐related disability and QoL to improve treatment, mitigate disability, and optimize health‐care resource utilization.

Clinical Implications

Although this cross‐sectional analysis does not support causal inferences, we show that at any headache frequency, levels of disability are greater in persons with migraine and depression or anxiety and particularly among those with both psychiatric comorbidities. Figure 4 suggests 2 approaches to improving disability. One approach is to reduce headache‐day frequency so that disability declines with leftward movement along 1 of the curves. One trial found that beta‐blocker, behavioral migraine treatment, or their combination (vs placebo) reduced headache disability to a greater extent in people with comorbid depression and/or anxiety disorders than in people without these comorbidities. 19 A second approach is to address depression, anxiety, or both in people with migraine and these comorbid disorders. Even if the frequency of headache days remains stable, relief of depression or anxiety could result in a downward shifting of curves, resulting in decreased disability at a particular level of headache frequency. Pain intensity and disability are correlated but not in a direct linear fashion, 39 further supporting the hypothesis that intervention in perception and coping skills such as those taught with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may help reduce disability. 40 These 2 approaches, reducing monthly headache days and reducing psychiatric comorbidities, provide alternative and perhaps complimentary approaches to reducing disability available for future testing.

Limitations

Limitations of this present study include the self‐reported nature of the data; clinically relevant depression and anxiety were determined by screening tests administered online and do not represent a diagnosis or examination by a health‐care professional. We used the validated sum scoring methods for the GAD‐7 and the PHQ‐9, which do not follow the DSM‐IV algorithm scoring approach which requires endorsement of the first 2 hallmark symptoms of depression; however, they are validated scoring methods and especially helpful for assessing severity. Although it could be argued that the data are subject to reporting bias by individual respondents, as with migraine, there are no lab tests or markers for depression and anxiety. Clinical diagnosis is determined through interview, where patients also self‐report both migraine and psychiatric symptoms to assess criteria and assign diagnosis. In addition, strong agreement has been reported between Internet‐based self‐reported and proxy‐reported data, supporting the validity of survey data. 41 Furthermore, although the present screening tools have been validated for depression and anxiety, 26 , 28 the GAD‐7 assesses symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder only; therefore, results do not generalize to other anxiety disorders such as panic disorder. Future studies of anxiety in people with migraine should consider inclusion of validated questionnaires that assess different anxiety features, such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory 42 and the Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire. 43 Although our results are similar to those reported elsewhere, observed discrepancies may result, including prevalence, in part, from differences in patient self‐reporting and health‐care professional diagnoses, the use of different assessment methodologies, and/or differences among populations. Given the observed bidirectionality between psychiatric comorbidities and migraine and the cross‐sectional nature of this current analysis, causality cannot be determined. Furthermore, rate ratios must be interpreted with caution because data related to potential confounding factors have not been collected or explored. Finally, because this is a subanalysis, the sample size was not predetermined to ensure sufficient study power to produce a statistically significant result. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with those of other studies, as described above.

Unraveling the present effect on disability at a mechanistic level is challenging because of the complex interactions of depression and anxiety symptoms comorbid with migraine and observed bidirectional associations. Many confounding factors could potentially contribute independently to disability, limiting our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the effects of depression and anxiety on headache‐related disability. Further investigations must be undertaken in a population with migraine and comorbid psychiatric disorders to confirm and further explore the findings of this analysis. Additional studies of the disability associated with other comorbid psychiatric disorders such as bipolar spectrum and personality disorders in people with migraine would also be of interest. A high proportion of people with recurrent depression have bipolar spectrum disorders and bipolar spectrum disorders are associated with somatic symptoms including headache. 44 , 45 Assessing these associations is an important task for future research.

Conclusions

Compared with respondents without either depression or anxiety, respondents with depression and anxiety reported higher levels of headache‐related disability. The greatest level of headache‐related disability occurred in respondents with both depression and anxiety. A significantly greater proportion of respondents with CM reported psychiatric comorbidities, consistent with the greater overall burden associated with CM than EM. Moreover, headache‐related disability increased with headache‐day frequency across the range of monthly headache days, suggesting a continuum of disability. Additional longitudinal analyses of the CaMEO Study data may provide further information on relationships among headache characteristics, comorbidities, and disability. From a clinical treatment perspective, the results reinforce the importance of managing the total burden of migraine, including disability, QoL, and associated comorbidities.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Category 1

(a) Conception and Design

Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn C. Buse, Kristina M. Fanning, Richard B. Lipton, Michael L. Reed

(b) Acquisition of Data

Kristina M. Fanning, Michael L. Reed

(c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Kristina M. Fanning (with input from all authors)

Category 2

(a) Drafting the Manuscript

Kristina M. Fanning, Michael L. Reed, Richard B. Lipton

(b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

Richard B. Lipton, Elizabeth K. Seng, Min Kyung Chu, Michael L. Reed, Kristina M. Fanning, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn C. Buse

Category 3

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Manuscript

Richard B. Lipton, Elizabeth K. Seng, Min Kyung Chu, Michael L. Reed, Kristina M. Fanning, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn C. Buse

Supporting information

Table S1

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by AbbVie. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. The authors received no honorarium/fee or other form of financial support related to the development of this article.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Buse has received grant support and honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Avanir, Eli Lilly and Company, Promius and Teva, although no payments were made by any of these companies for work writing abstracts, scientific presentations, or manuscripts. She is on the editorial board of Current Pain and Headache Reports. Dr. Seng receives research support from NINDS (K23 NS096107 PI: Seng); has consulted for Eli Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received honoraria from Haymarket Media. Dr. Chu has received honoraria from AbbVie Korea and YuYu Pharma, Inc. Dr. Reed is Managing Director of Vedanta Research, which has received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories/Promius, and Eli Lilly, and grants from the National Headache Foundation. Vedanta Research has received funding directly from AbbVie for work on the CaMEO Study. Dr. Fanning is an employee of Vedanta Research, which has received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories/Promius, and Eli Lilly, and grants from the National Headache Foundation. Vedanta Research has received funding directly from AbbVie for work on the CaMEO Study. Dr. Manack Adams is a full‐time employee of AbbVie and owns stock in the company. Dr. Lipton serves on the editorial boards of Neurology and Cephalalgia, and as senior advisor to Headache. He has received research support from the NIH. He also receives support from the Migraine Research Foundation and the National Headache Foundation. He has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS and serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, AbbVie, Amgen, Autonomic Technologies, Avanir, Biohaven, Biovision, Boston Scientific, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, electroCore, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pernix, Pfizer, Supernus, Teva, Vector, and Vedanta. He receives royalties from Wolff's Headache (eighth Edition, Oxford University Press), Informa, and Wiley. He holds stock options in Biohaven and eNeura Therapeutics.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01648530.

REFERENCES

- 1. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA. Pathophysiology of migraine. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:365‐391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990‐2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211‐1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46:1327‐1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seng EK, Seng CD. Understanding migraine and psychiatric comorbidity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29:309‐313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peres MFP, Mercante JPP, Tobo PR, Kamei H, Bigal ME. Anxiety and depression symptoms and migraine: A symptom‐based approach research. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lanteri‐Minet M, Radat F, Chautard MH, Lucas C. Anxiety and depression associated with migraine: Influence on migraine subjects' disability and quality of life, and acute migraine management. Pain. 2005;118:319‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. Anxious and non‐anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psych Sci. 2015;24:210‐226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Kroon Van Diest A, et al. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:741‐749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ashina S, Serrano D, Lipton RB, et al. Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:615‐624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breslau N, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Schultz LR, Welch KM. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: Investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology. 2003;60:1308‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Y, Zhao H, Boomsma DI, et al. Molecular genetic overlap between migraine and major depressive disorder. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:1202‐1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu J, Davis‐Ajami ML, Kevin Lu Z. Impact of depression on health and medical care utilization and expenses in US adults with migraine: A retrospective cross sectional study. Headache. 2016;56:1147‐1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zebenholzer K, Andree C, Lechner A, et al. Prevalence, management and burden of episodic and chronic headaches–A cross‐sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF. Migraine, quality of life, and depression: A population‐based case‐control study. Neurology. 2000;55:629‐635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seng EK, Buse DC, Klepper JE, et al. Psychological factors associated with chronic migraine and severe migraine‐related disability: An observational study in a tertiary headache center. Headache. 2017;57:593‐604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seng EK, Holroyd KA. Psychiatric comorbidity and response to preventative therapy in the treatment of severe migraine trial. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:390‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seng EK, Holroyd KA. Behavioral migraine management modifies behavioral and cognitive coping in people with migraine. Headache. 2014;54:1470‐1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manack Adams A, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:563‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: Results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2016;56:821‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: Results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:638‐645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near‐daily headaches: Field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache‐related disability. Neurology. 2001;56:S20‐S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ‐9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD‐7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092‐1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwedt TJ, Alam A, Reed ML, et al. Factors associated with acute medication overuse in people with migraine: Results from the 2017 migraine in America symptoms and treatment (MAST) study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Ashina S, et al. Cutaneous allodynia in the migraine population. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:148‐158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baldacci F, Lucchesi C, Cafalli M, et al. Migraine features in migraineurs with and without anxiety‐depression symptoms: A hospital‐based study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;132:74‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cassidy EM, Tomkins E, Hardiman O, O'Keane V. Factors associated with burden of primary headache in a specialty clinic. Headache. 2003;43:638‐644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Juang KD, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Su TP. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its subtypes. Headache. 2000;40:818‐823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim SY, Park SP. The role of headache chronicity among predictors contributing to quality of life in patients with migraine: A hospital‐based study. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saunders K, Merikangas K, Low NC, Von Korff M, Kessler RC. Impact of comorbidity on headache‐related disability. Neurology. 2008;70:538‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Breslau N, Davis GC. Migraine, physical health and psychiatric disorder: A prospective epidemiologic study in young adults. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:211‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lipton RB, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML. A Comparison of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study and American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study: Demographics and headache‐related disability. Headache. 2016;56:1280‐1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oh K, Cho SJ, Chung YK, Kim JM, Chu MK. Combination of anxiety and depression is associated with an increased headache frequency in migraineurs: A population‐based study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stewart WF, Shechter A, Lipton RB. Migraine heterogeneity. Disability, pain intensity, and attack frequency and duration. Neurology. 1994;44:S24‐S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin PR, Aiello R, Gilson K, Meadows G, Milgrom J, Reece J. Cognitive behavior therapy for comorbid migraine and/or tension‐type headache and major depressive disorder: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2015;73:8‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palmer L, Johnston SS, Rousculp MD, Chu BC, Nichol KL, Mahadevia PJ. Agreement between Internet‐based self‐ and proxy‐reported health care resource utilization and administrative health care claims. Value Health. 2012;15:458‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893‐897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baker A, Simon N, Keshaviah A, et al. Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (ASQ): Development and validation. Gen Psychiatry. 2019;32:e100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lövdahl H, Bøen E, Malt EA, Malt UF. Somatic and cognitive symptoms as indicators of potential endophenotypes in bipolar spectrum disorders: An exploratory and proof‐of‐concept study comparing bipolar II disorder with recurrent brief depression and healthy controls. J Affect Disord. 2014;166:59‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith DJ, Harrison N, Muir W, Blackwood DH. The high prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorders in young adults with recurrent depression: Toward an innovative diagnostic framework. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:167‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1