Summary

Background

Plaque psoriasis affects children and adults, but treatment options for paediatric psoriasis are limited.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab (IXE), a high‐affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin‐17A, for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis.

Methods

In a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase III study (IXORA‐PEDS), patients aged 6 to < 18 years with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis were randomized 2 : 1 to weight‐based dosing of IXE every 4 weeks (IXE Q4W, n = 115) or placebo (n = 56) through week 12, followed by open‐label IXE Q4W. Coprimary endpoints were the proportions of patients at week 12 achieving ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) and those achieving a static Physician's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (sPGA 0,1).

Results

IXE was superior (P < 0·001) to placebo for both coprimary endpoints of PASI 75 (IXE Q4W, 89%; placebo, 25%) and sPGA (0,1) (IXE Q4W, 81%; placebo, 11%). IXE was also superior for all gated secondary endpoints, including PASI 75 and sPGA (0,1) at week 4, improvement in itch, and complete skin clearance. IXE Q4W provided significant (P < 0·001) improvements vs. placebo in quality of life and clearance of scalp and genital psoriasis. Responses at week 12 were sustained or further improved through week 48. Through week 12, 45% (placebo) and 56% (IXE) of patients reported treatment‐emergent adverse events. One serious adverse event was reported (IXE), one patient discontinued due to an adverse event (placebo) and no deaths were reported.

Conclusions

IXE was superior to placebo in the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis, and the safety profile was generally consistent with that observed in adults.

What is already known about this topic?

Paediatric psoriasis affects approximately 1% of children and can negatively impact health‐related quality of life.

Treatment options for paediatric psoriasis are typically limited to off‐label treatments and approved systemic biologics.

Ixekizumab, a high‐affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin‐17A, is approved for moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis in adults and was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis.

What does this study add?

Ixekizumab resulted in rapid and statistically significant improvements over placebo in skin involvement, itch and health‐related quality of life, which persisted through 48 weeks of treatment in paediatric patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis.

The safety profile of ixekizumab was generally consistent with that seen in adults.

Ixekizumab may be an additional potential therapeutic option and an additional class of biologic therapy (interleukin‐17A antagonist) for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis.

Plain language summary available online

Paediatric plaque psoriasis affects approximately 1% of children and adolescents, and is estimated to occur first before 20 years of age in 35–50% of adults with plaque psoriasis.1, 2, 3 Paediatric psoriasis can be associated with reduced quality of life and a higher incidence of multiple comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis, obesity, diabetes, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and psychiatric comorbidities.4 Thus, early recognition and treatment of paediatric psoriasis are important for overall health and quality of life.

As there have been few clinical studies of paediatric psoriasis, treatment options are limited and often used off‐label. Topical therapies comprise first‐line treatment, followed by phototherapy for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis.5 Systemic treatments are recommended for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis recalcitrant to topical therapies.5, 6 Nonbiologic systemic treatments such as methotrexate or ciclosporin are used, but they may not be well tolerated or provide adequate efficacy.5, 6

Ixekizumab (IXE) is a high‐affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin‐(IL)‐17A. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of IXE for moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis in paediatric patients aged 6 to < 18 years. Prior to the current study, two tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (etanercept and adalimumab) and one IL‐12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab) were approved for paediatric psoriasis.7 Based on the findings from this study, IXE was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis in addition to previously approved indications for adult patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Patients and methods

Patients

Study participants were 6 to < 18 years of age and had moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis, defined as Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) ≥ 12, static Physician's Global Assessment (sPGA) ≥ 3 and psoriasis‐affected body surface area ≥ 10% at screening and baseline. They were also candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy or their psoriasis was not adequately controlled by topical therapies as determined by the investigator. Patients with pustular, erythrodermic and/or guttate forms of plaque psoriasis or drug‐induced psoriasis, or with clinical and/or laboratory evidence of untreated latent or active tuberculosis were excluded. Appendix S2 (see Supporting Information) provides complete eligibility criteria.

Study design

IXORA‐PEDS is a 108‐week multicentre, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled, phase III study examining the efficacy and safety of IXE vs. placebo in paediatric patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. During a 12‐week double‐blind treatment period, patients were randomized 2 : 1 to subcutaneous IXE every 4 weeks (Q4W) or placebo, administered according to baseline weight categories of > 50 kg, 25–50 kg and < 25 kg (Table S1; see Supporting Information). As part of a European Union protocol addendum, an etanercept reference arm was included in IXORA‐PEDS to demonstrate the efficacy of IXE in the context of an approved therapy for paediatric psoriasis. At the time of trial commencement, etanercept was approved only for severe psoriasis in paediatric patients in the European Union. Therefore, patients with severe psoriasis (PASI ≥ 20 or sPGA ≥ 4) at baseline in countries where etanercept is approved only for severe paediatric psoriasis were eligible for inclusion in the protocol addendum. These patients were randomized 2 : 2 : 1 to IXE Q4W, open‐label etanercept (0·8 mg kg−1 every 1 week, not exceeding 50 mg per dose) or placebo until approximately 75 patients were randomized. Efficacy assessments were conducted by blinded assessors to minimize potential bias in assessments of patients receiving open‐label etanercept.

Patients completing the double‐blind treatment period entered a 48‐week open‐label maintenance period (week 12 to week 60), during which patients initially randomized to IXE Q4W or placebo received IXE Q4W and patients initially randomized to etanercept received IXE Q4W after an 8‐week washout period.

Enrolment for IXORA‐PEDS occurred between 17 April 2017 and 13 November 2018. At the time of publication of this report, the study is currently ongoing. IXORA‐PEDS (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03073200) was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethical review board at each participating site. A parent or legal guardian provided written informed consent and the patient provided written assent prior to conduct of study assessments, examinations or procedures. Appendix S3 (see Supporting Information) provides additional details on the study design.

Outcomes

The prespecified coprimary objectives of the study were to assess whether IXE Q4W was superior to placebo at week 12 as measured by the proportions of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement from baseline in PASI (PASI 75) and an sPGA score of 0 or 1 [sPGA (0,1)]. The prespecified gated secondary objectives were to assess whether IXE Q4W was superior to placebo at week 12, as measured by the proportion of patients achieving PASI 90, an sPGA score of 0 [sPGA (0)], PASI 100 and ≥ 4‐point improvement from baseline in the Itch Numerical Rating Scale (Itch NRS ≥ 4, in patients with baseline score ≥ 4); as well as PASI 75 and sPGA (0,1) at week 4. Other prespecified secondary outcomes included a 0 or 1 score on the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI, patients aged 6–16 years) or Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI, patients aged ≥ 17 years), a score of 0 or 1 on the Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Severity [PatGA (0,1)], a Nail Psoriasis Severity Index score of 0 (NAPSI = 0, in patients with baseline NAPSI > 0), a Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index score of 0 (PSSI = 0, in patients with baseline PSSI > 0), 100% improvement from baseline in the Palmoplantar Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PPASI 100, in patients with baseline PPASI > 0), clearance of genital psoriasis (in patients with baseline genital psoriasis), mean change from baseline in Itch NRS, and mean change from baseline in NAPSI, PSSI and PPASI for patients with baseline NAPSI > 0, PSSI > 0 and PPASI > 0, respectively. Appendixes S4 and S5 (see Supporting Information) provide further details on the objectives and outcomes.

Safety outcomes included assessments of adverse events (AEs) – including treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs), serious AEs (SAEs) and AEs of special interest – laboratory tests and vital signs. Data on suspected inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were adjudicated by an external clinical events committee. Appendixes S3 and S6 (see Supporting Information) provide details on antidrug antibody assays and safety outcomes.

Statistical analyses

A gated multiple testing strategy was implemented for the primary and major secondary objectives to control the family‐wise type I error rate at a two‐sided α‐level of 0·05. To assess whether IXE Q4W was superior to placebo, the primary and gated secondary endpoints were tested sequentially. If any test was not successful, all subsequent tests were not tested.

Analyses are provided for the week 12 and week 48 database locks. Efficacy analyses during the double‐blind treatment period were performed on all randomized patients according to the initially assigned treatment. Efficacy was also summarized using descriptive statistics for all patients randomized to IXE at week 0 who received IXE throughout their study participation up to week 48. Additional efficacy analyses were performed according to the initially assigned treatment on all randomized patients with severe psoriasis in countries where etanercept was approved for severe psoriasis. Efficacy was also analysed according to baseline weight category (< 25 kg, ≥ 25 kg to ≤ 50 kg and > 50 kg).

Treatment group comparisons for categorical outcomes were performed using Fisher's exact test with nonresponder imputation for handling of missing data. Continuous outcomes were analysed using a mixed model for repeated‐measures analysis, including treatment, region, baseline sPGA score, baseline weight category, baseline value, visit, treatment‐by‐visit and baseline‐by‐visit interactions as fixed factors. Type III tests for the least‐squares means were used for statistical comparisons. Table S2 (see Supporting Information) lists the number of patients with nonmissing data at each postbaseline visit through week 48.

Safety was summarized using descriptive statistics. Safety analyses during the double‐blind treatment period were performed on all randomized patients who took at least one dose of double‐blind study treatment according to the initially assigned treatment. Safety was also summarized up to the week 48 interim database lock for the all‐IXE safety population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of IXE, including patients initially randomized to placebo or etanercept. Additional safety analyses were conducted in all randomized patients in etanercept‐approved countries who took at least one dose of double‐blind study treatment according to the initially assigned treatment.

Analyses of antidrug antibodies were conducted on all evaluable patients in the all‐IXE safety population. Patients with treatment‐emergent antidrug antibodies (TE‐ADAs) were classified as having low, moderate or high titre if their last titre value within the baseline or postbaseline period was < 1 : 160, ≥ 1 : 160 to < 1 : 1280, or ≥ 1 : 1280, respectively. Appendix S7 (see Supporting Information) provides additional information on the statistical analyses.

Results

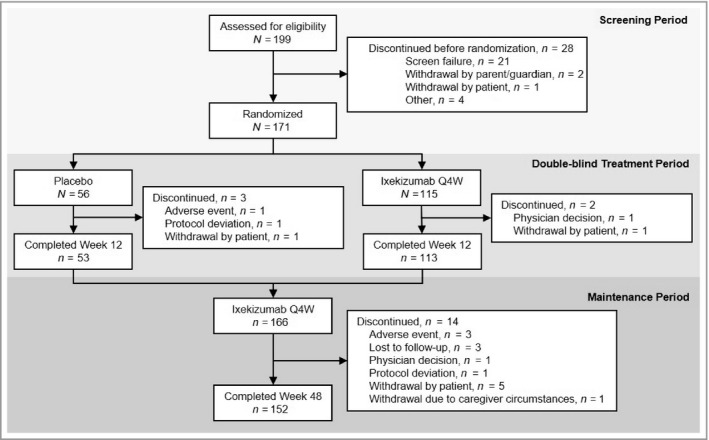

Of 199 patients screened, 171 (86%) were randomized to placebo (n = 56) or IXE Q4W (n = 115); 53 (95%) and 113 (98%), respectively, completed the double‐blind treatment period (Figure 1). Overall, 166 patients entered the maintenance period and 89% (152 of 171) completed week 48. Three (placebo) and two (IXE Q4W) patients discontinued during the double‐blind treatment period and 14 discontinued during the maintenance period. Figure S1 (see Supporting Information) presents a flow diagram for patients with severe psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram through Week 48 of IXORA‐PEDS. Q4W, every 4 weeks.

The baseline demographics and disease characteristics were similar between treatment arms (Table 1; and Table S3; see Supporting Information). The mean ± SD age was 13·5 ± 3·04 years (range 6–17), 58% (n = 99) of patients were female, and most (84%, n = 140) were of white race. Most patients (73%, n = 125) weighed > 50 kg, 25% (n = 43) weighed ≥ 25 and ≤ 50 kg, and 2% (n = 3) weighed < 25 kg. The mean ± SD duration of psoriasis symptoms was 4·7 ± 3·17 years and the mean ± SD PASI score was 19·7 ± 7·65. Baseline nail (NAPSI > 0), scalp (PSSI > 0), palmoplantar (PPASI > 0) and genital psoriasis were present for 27% (n = 46), 89% (n = 152), 15% (n = 26) and 32% (n = 55) of patients, respectively. Most patients (72%, n = 123) had baseline Itch NRS ≥ 4 and all patients (n = 171) had baseline PatGA > 0. The mean ± SD DLQI and CLDQI scores were 9·4 ± 4·92 and 8·1 ± 5·30, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Placebo (n = 56) | IXE Q4W (n = 115) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 13·1 ± 2·79 | 13·7 ± 3·14 |

| Female sex | 36 (64) | 63 (55) |

| White racea | 45 (85) | 95 (83) |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 60·3 ± 20·33 | 63·9 ± 24·94 |

| < 25 kg | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| ≥ 25 kg and ≤ 50 kg | 14 (25) | 29 (25) |

| > 50 kg | 41 (73) | 84 (73) |

| BMI (kg m−2), mean ± SD | 23·5 ± 5·57 | 24·1 ± 6·77 |

| Duration of psoriasis since diagnosis (years), mean ± SD | 4·7 ± 3·01 | 4·7 ± 3·26 |

| Prior psoriasis treatment | ||

| Nonbiologic systemic | 15 (27) | 39 (34) |

| Biologic | 2 (4) | 5 (4) |

| Phototherapy | 13 (23) | 25 (22) |

| Involved BSA (%), mean ± SD | 27·1 ± 17·27 | 27·1 ± 18·55 |

| sPGA score, mean ± SD | 3·5 ± 0·6 | 3·6 ± 0·6 |

| sPGA = 3 | 31 (55) | 57 (50) |

| sPGA = 4 | 21 (38) | 51 (44) |

| sPGA = 5 | 4 (7) | 7 (6) |

| PASI, mean ± SD | 19·7 ± 8·01 | 19·8 ± 7·51 |

| NAPSI, mean ± SDb | 24·5 ± 20·86 | 33·9 ± 29·52 |

| NAPSI > 0 | 12 (21) | 34 (30) |

| PSSI, mean ± SDc | 29·7 ± 17·24 | 27·3 ± 17·01 |

| PSSI > 0 | 50 (89) | 102 (89) |

| PPASI, mean ± SDd | 15·4 ± 21·08 | 8·2 ± 8·67 |

| PPASI > 0 | 9 (16) | 17 (15) |

| Itch NRS, mean ± SD | 5·0 ± 2·47 | 5·4 ± 2·75 |

| Itch NRS ≥ 4 | 40 (71) | 83 (72) |

| CDLQI, mean ± SDe | 7·4 ± 4·78 | 8·5 ± 5·54 |

| DLQI, mean ± SDf | 10·2 ± 5·42 | 9·3 ± 4·90 |

| PatGA, mean ± SD | 3·5 ± 0·97 | 3·6 ± 1·08 |

| PatGA > 0 | 56 (100) | 115 (100) |

| Genital psoriasis present | 14 (25) | 41 (36) |

Unless otherwise specified, data are presented as n (%). Values are reported as observed. Unless otherwise indicated, there were no missing values in the baseline characteristics. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CDLQI, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; IXE, ixekizumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NRS, numerical rating scale; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PatGA, Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Severity; PPASI, Palmoplantar Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PSSI, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index; Q4W, every 4 weeks; sPGA, static Physician's Global Assessment. aNumber of patients with nonmissing values: placebo, n = 53; IXE Q4W, n = 114. bAssessed for patients with nail psoriasis at baseline (as reported by the investigator). Number of patients with non‐missing values: placebo, n = 13; IXE Q4W, n = 34. cAssessed for patients with scalp psoriasis at baseline (as reported by the investigator). Number of patients with non‐missing values: placebo, n = 50; IXE Q4W, n = 103. dAssessed for patients with palmoplantar psoriasis at baseline (as reported by the investigator). Number of patients with non‐missing values: placebo, n = 9; IXE Q4W, n = 18. eAssessed in patients 6–16 years of age. Number of patients with nonmissing values: placebo, n = 48; IXE Q4W, n = 86. fAssessed in patients ≥ 17 years of age. Number of patients with nonmissing values: placebo, n = 6; IXE Q4W, n = 26.

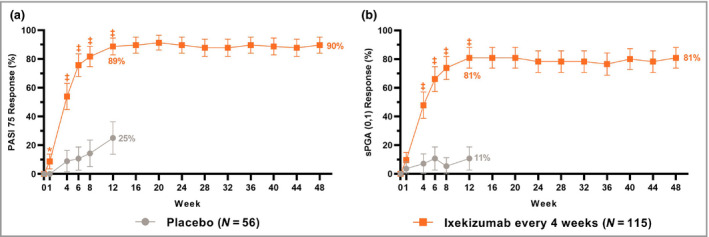

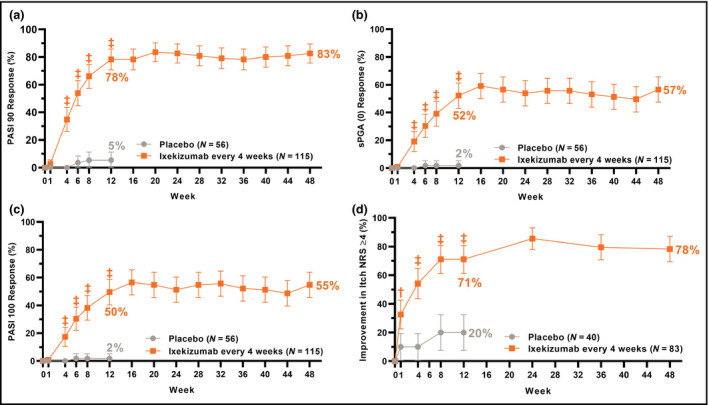

The coprimary and all gated secondary objectives were achieved. IXE was superior to placebo for both coprimary endpoints of PASI 75 (IXE Q4W: 89%, placebo: 25%, P < 0·001) and sPGA (0,1) (IXE Q4W: 81%, placebo: 11%, P < 0·001) at week 12 (Figure 2 and Table 2). IXE was superior to placebo at week 12 for the gated secondary endpoints of PASI 90 (IXE Q4W: 78%, placebo: 5%, P < 0·001), sPGA (0) (IXE Q4W: 52%, placebo: 2%, P < 0·001), PASI 100 (IXE Q4W: 50%, placebo: 2%, P < 0·001) and Itch NRS ≥ 4 (IXE Q4W: 71%, placebo: 20%, P < 0·001) (Figure 3 and Table 2); and at week 4 for PASI 75 (IXE Q4W: 54%, placebo: 9%, P < 0·001) and sPGA (0,1) (IXE Q4W: 48%, placebo: 7%, P < 0·001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients achieving (a) ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) and (b) static Physician's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 [sPGA (0,1)] for up to 48 weeks of treatment with ixekizumab (nonresponder imputation). Ixekizumab vs. placebo P‐values during the 12‐week double‐blind treatment period are indicated as *P < 0·05, ‡P < 0·001. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Analyses of PASI 75 and sPGA (0,1) at week 12 (coprimary endpoints) and at week 4 (gated secondary endpoints) were included in the gated multiple testing strategy. Analyses at other timepoints were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes at weeks 12 and 48

| Week 12 | Week 48 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 56) | IXE Q4W (n = 115) | IXE Q4W vs. placebo | IXE Q4W (n = 115) | ||

| Response n (%) | Response n (%) | P‐value | Difference vs. placebo (95% CI) | Response n (%) | |

| PASI 50 | 21 (38) | 106 (92) | < 0·001 | 54·7% (41·1–68·3) | 106 (92) |

| PASI 75 | 14 (25) | 102 (89) | < 0·001 | 63·7% (51·0–76·4) | 103 (90) |

| PASI 90 | 3 (5) | 90 (78) | < 0·001 | 72·9% (63·3–82·5) | 95 (83) |

| PASI 100 | 1 (2) | 57 (50) | < 0·001 | 47·8% (38·0–57·6) | 63 (55) |

| sPGA 0 or 1 | 6 (11) | 93 (81) | < 0·001 | 70·2% (59·3–81·0) | 93 (81) |

| sPGA 0 | 1 (2) | 60 (52) | < 0·001 | 50·4% (40·6–60·2) | 65 (57) |

| Itch NRS ≥ 4a | 8 (20) | 59 (71) | < 0·001 | 51·1% (35·3–66·9) | 65 (78) |

| CDLQI/DLQI 0 or 1b | 13 (23) | 74 (64) | < 0·001 | 41·1% (27·0–55·2) | 87 (76) |

| PatGA 0 or 1 | 9 (16) | 91 (79) | < 0·001 | 63·1% (50·9–75·2) | 99 (86) |

| NAPSI = 0c | 0 | 6 (18) | 0·317 | 17·6% (4·8–30·5) | 17 (50) |

| PSSI = 0d | 8 (16) | 70 (69) | < 0·001 | 52·6% (39·1–66·2) | 75 (74) |

| PPASI 100e | 1 (11) | 8 (47) | 0·098 | 35·9% (4·6–67·3) | 13 (76) |

| Clearance of genital psoriasisf | 5 (36) | 35 (85) | < 0·001 | 49·7% (22·3–77·0) | 37 (90) |

| Response, LSM CFB ± SD | Response, LSM CFB ± SD | P‐value | Difference vs. placebo, LSM difference ± SE | Response, LSM CFB ± SE | |

| Itch NRS | −0·43 ± 0·44 | −3·15 ± 0·40 | < 0·001 | −2·72 ± 0·33 | −3·46 ± 0·40 |

| NAPSIc | 0·17 ± 5·33 | −16·87 ± 3·11 | 0·005 | −17·04 ± 5·75 | −31·17 ± 2·18 |

| PSSId | −12·28 ± 2·57 | −27·64 ± 2·32 | < 0·001 | −15·36 ± 1·68 | −25·72 ± 1·30 |

| PPASIe | 6·89 ± 3·38 | −5·11 ± 2·15 | 0·006 | −12·01 ± 3·85 | −9·04 ± 0·26 |

Unless otherwise specified, values are presented as the number of responders (%). Categorical outcomes: Fisher's exact test with nonresponder imputation for handling missing data. Continuous outcomes: mixed model for repeated‐measures analysis. Type III tests for least‐squares means (LSMs) was used for treatment group comparisons. CDLQI, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; CFB, change from baseline; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; IXE, ixekizumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NRS, numerical rating scale; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PatGA, Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Severity; PPASI, Palmoplantar Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PSSI, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index; Q4W, every 4 weeks; sPGA, static Physician's Global Assessment. aAssessed for patients with baseline itch NRS ≥ 4. Placebo, n = 40; IXE Q4W, n = 83. bCDLQI was assessed for patients 6–16 years of age. DLQI was assessed for patients ≥ 17 years of age. cAssessed for patients with baseline NAPSI > 0. Placebo, n = 12; IXE Q4W, n = 34. dAssessed for patients with baseline PSSI > 0. Placebo, n = 50; IXE Q4W, n = 102. eAssessed for patients with baseline PPASI > 0. Placebo, n = 9; IXE Q4W, n = 17. fAssessed for patients with genital psoriasis at baseline.

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients achieving (a) ≥ 90% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90); (b) static Physician's Global Assessment score of 0 [sPGA (0)]; (c) PASI 100 and (d) ≥ 4‐point improvement from baseline in itch numerical rating scale (Itch NRS) for up to 48 weeks of treatment with ixekizumab (nonresponder imputation). Ixekizumab vs. placebo P‐values during the 12‐week double‐blind treatment period are indicated as †P < 0·01, ‡P < 0·001. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Analyses of PASI 90, sPGA (0), PASI 100 and Itch NRS ≥ 4 at week 12 (gated secondary endpoints) were included in the gated multiple testing strategy. Analyses at other timepoints were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Significantly (P < 0·001) more patients achieved PASI 50 at week 12 with IXE Q4W (92%) than with placebo (38%) (Table 2), with significant differences as early as week 1 (IXE Q4W: 36%, placebo: 7%, P < 0·001). IXE provided significant improvements over placebo as early as week 1 for PASI 75 (P = 0·032) and Itch NRS ≥ 4 (P = 0·008), and as early as week 4 (P < 0·001) for PASI 90, PASI 100, sPGA (0,1) and sPGA (0) (Figures 2 and 3). In patients with severe psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries, IXE resulted in significantly greater response than etanercept for PASI 90 (IXE Q4W: 76%, etanercept: 40%, P = 0·003), PASI 100 (IXE Q4W: 61%, etanercept: 53%, P < 0·001) and sPGA 0 (IXE Q4W: 63%, etanercept: 17%, P < 0·001). Responses with IXE Q4W were numerically greater than with etanercept for PASI 75 (IXE Q4W: 84%, etanercept: 63%, P = 0·089) and sPGA (0,1) (IXE Q4W: 76%, etanercept: 53%, P = 0·070), but were not statistically significant (Table 3; and Figure S2; see Supporting Information).

Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes at week 12 in patients with severe psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries

| Placebo (n = 19) | ETN (n = 30) | IXE Q4W (n = 38) | IXE Q4W vs. ETN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Response | Response | P‐value | Difference IXE vs. ETN (95% CI) | |

| PASI 75 | 5 (26) | 19 (63) | 32 (84) | 0·089 | 20·9% (0·1–41·7) |

| PASI 90 | 0 | 12 (40) | 29 (76) | 0·003 | 36·3% (14·2–58·5) |

| PASI 100 | 0 | 5 (17) | 23 (61) | < 0·001 | 43·9% (23·4–64·3) |

| sPGA 0 or 1 | 1 (5) | 16 (53) | 29 (76) | 0·070 | 23·0% (0·6–45·4) |

| sPGA 0 | 0 | 5 (17) | 24 (63) | < 0·001 | 46·5% (26·2–66·8) |

Values are presented as the number of responders (%). Fisher's exact test with nonresponder imputation was used to handle missing data. CI, confidence interval; ETN, etanercept; IXE, ixekizumab; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q4W, every 4 weeks; sPGA, static Physician's Global Assessment.

CDLQI/DLQI (0,1) and PatGA (0,1) responses at week 12 were significantly (P < 0·001) greater with IXE than with placebo (Table 2). At week 12, significantly more patients with IXE than with placebo achieved clearance of baseline scalp (PSSI = 0, P < 0·001) and genital psoriasis (P < 0·001). IXE Q4W resulted in a significantly greater mean change from baseline than placebo at week 12 for Itch NRS (P < 0·001), NAPSI (P = 0·005), PSSI (P < 0·001) and PPASI (P = 0·006).

Responses at week 12 were sustained or further improved through week 48 (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 2). For patients initially randomized to IXE Q4W, responses at week 48 were 92% (PASI 50), 90% (PASI 75), 83% (PASI 90), 55% (PASI 100), 81% [sPGA (0,1)], 57% [sPGA (0)] and 78% (Itch NRS ≥ 4). Sustained or additional improvements through week 48 were observed for CDLQI/DLQI (0,1), PatGA (0,1) and clearance of nail, scalp, palmoplantar or genital psoriasis.

In analyses by baseline weight, IXE resulted in significantly greater responses than placebo at week 12 for PASI 75, PASI 90, PASI 100, sPGA (0,1) and sPGA (0) in the subgroups of ≥ 25 kg to ≤ 50 kg and > 50 kg, and responses with IXE Q4W were numerically similar between these two subgroups (Table S4; see Supporting Information). Statistical comparisons of responses in patients with baseline weight < 25 kg were limited due to the small number of patients in this category (placebo: n = 1, IXE Q4W: n = 2). Both patients receiving IXE Q4W achieved PASI 75 and one (50%) achieved PASI 90, PASI 100, sPGA (0,1) and sPGA (0) at week 12; the patient receiving placebo achieved none of these endpoints.

During the double‐blind treatment period, TEAEs were reported in 64 (56%) and 25 (45%) patients receiving IXE Q4W and placebo, respectively; no TEAEs were severe (Table 4). One (1%) SAE (IXE Q4W) was reported and one (2%) patient (placebo) discontinued due to an AE. In the all‐IXE safety population, TEAEs occurred in 161 (82%) patients; nine (5%) were severe. Thirteen patients (7%) reported SAEs (Table S5; see Supporting Information) and three (2%) discontinued due to an AE (two with Crohn's disease and one with pityriasis rubra pilaris). In the etanercept arm, 13 patients (43%) reported TEAEs (two severe, 7%), one (3%) SAE was reported, and there were no discontinuations due to AEs (Table S6; see Supporting Information). No deaths were reported.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events

| Safety populationa (double‐blind treatment period) | All‐IXE safety populationb (all treatment periods) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 56) | IXE Q4W (n = 115) | IXE Q4W (n = 196) | |

| Patient‐years of exposure | 26·9 | 12·9 | 253·9 |

| Treatment‐emergent adverse events | 25 (45) | 64 (56) | 161 (82) |

| Mild | 16 (29) | 47 (41) | 80 (41) |

| Moderate | 9 (16) | 17 (15) | 72 (37) |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 9 (5) |

| Discontinuation due to adverse event | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Serious adverse events | 0 | 1 (1) | 13 (7) |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse events of special interest | |||

| Infections | 14 (25) | 37 (32) | 129 (66) |

| Serious infections | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Opportunistic infections | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection‐site reactions | 1 (2) | 14 (12) | 39 (20) |

| Allergic reactions/hypersensitivty | 1 (2) | 6 (5) | 16 (8) |

| Potential anaphylaxis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cytopenia | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Hepatic | 0 | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Malignancies | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 0 | 1 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IBD | 0 | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Crohn's disease | 0 | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The data are presented as n (%). (Except patient‐years of exposure.) IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IXE, ixekizumab; Q4W, every 4 weeks. aIncludes all randomized patients who took at least one dose of double‐blind study treatment according to the treatment to which they were assigned. bIncludes all patients who received at least one dose of IXE, including those randomized to placebo or etanercept at week 0 who received open‐label IXE Q4W during the maintenance period.

During the double‐blind treatment period, treatment‐emergent infections were reported in 37 (32%) patients receiving IXE Q4W and 14 (25%) receiving placebo; no serious infections were reported. In the all‐IXE safety population, 129 (66%) patients reported treatment‐emergent infections; one (1%) was severe (pharyngitis). Two (1%) patients reported serious infections (one acute otitis media and one tonsillitis) and no opportunistic infections were reported. In the etanercept arm, six (20%) infection‐related TEAEs were reported and there were no serious infections.

During the double‐blind treatment period, 14 (12%) patients receiving IXE Q4W and one (2%) receiving placebo reported injection‐site reactions. In the all‐IXE safety population, 39 (20%) patients reported injection‐site reactions. There were no injection‐site‐related SAEs, and one severe injection‐site reaction (injection‐site pain) was reported. Safety related to depression, allergic reaction or hypersensitivity, cytopenia, and hepatic events is summarized in Table 4; none of which were SAEs. There were no TEAEs of grade 3 or 4 cytopenia reported and there were no reports of anaphylaxis, malignancies, or interstitial lung disease.

One patient receiving IXE Q4W reported an AE of diarrhoea during the double‐blind treatment period. This patient also reported intestinal inflammatory disease and abdominal pain at study day 1. The patient discontinued due to the AE of intestinal inflammatory disease and the case was adjudicated as probable Crohn's disease. Three patients reported TEAEs of IBD (adjudicated as probable Crohn's disease) during the maintenance period, each of whom reported SAEs and discontinued from the study. These discontinuations were due to withdrawal by patient (n = 1), AE of Crohn's disease (n = 1) and physician decision because of suspected IBD (n = 1). One of these patients reported autoimmune comorbidities of atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata and psoriatic arthritis. Appendix S8 (see Supporting Information) provides additional details regarding safety.

Of 194 evaluable patients, 53 (27%) were TE‐ADA positive; 29 (15%) were low titre, 22 (11%) were moderate titre and two (1%) were high titre. Neutralizing antidrug antibodies were detected in five (3%) evaluable patients. The presence of TE‐ADAs had no impact on efficacy regardless of neutralizing antibody status, and there were no consistent temporal relationships between the presence of TE‐ADAs and the occurrence of injection‐site reactions or allergic reaction or hypersensitivity TEAEs.

Discussion

IXE was superior to placebo for both coprimary endpoints and all gated secondary endpoints. Significant improvements in skin and itch were observed as early as week 1 and persisted through week 48. Itch affects many paediatric patients with psoriasis and has a high impact on quality of life.8, 9 In IXORA‐PEDS, nearly 75% of patients reported Itch NRS ≥ 4 at baseline. IXE provided clinically meaningful improvements in itch for nearly 80% of patients by week 48. IXE also provided significant improvements over placebo at week 12 in health‐related quality of life and clearance of scalp and genital psoriasis. Responses with IXE were generally consistent across weight subgroups, although analysis in patients with baseline weight < 25 kg was limited by the small sample size.

Most AEs were mild to moderate in severity, SAEs occurred in < 7% of patients, < 2% of patients discontinued due to AEs, and no deaths occurred. Serious infections were reported in approximately 1% of patients, but there were no discontinuations due to infection‐related TEAEs. Crohn's disease was reported in one patient during the double‐blind treatment period and in three patients during the maintenance period, each adjudicated as probable Crohn's disease.

PASI 75 was achieved by 89% of patients receiving IXE Q4W at week 12, a result consistent with the phase III UNCOVER‐1 (89%), UNCOVER‐2 (90%) and UNCOVER‐3 studies (87%) in adult patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis.10, 11 PASI 75 responses persisted through week 48 (90%), which was greater than week 60 responses in UNCOVER‐3 (83%).10 More patients achieved complete skin clearance (PASI 100) with IXE at week 12 in IXORA‐PEDS (50%) than in UNCOVER‐3 (38%), but responses were similar between IXORA‐PEDS (55%) at week 48 and UNCOVER‐3 (55%) at week 60. Placebo responses in IXORA‐PEDS were greater than those observed in adults in the UNCOVER studies. At week 12, PASI 75 was achieved by 25% of paediatric patients receiving placebo in IXORA‐PEDS, compared with 3·9% (UNCOVER‐1), 2·4% (UNCOVER‐2) and 7·3% (UNCOVER‐3) in adult patients.10, 11 These findings are consistent with conclusions from reviews and meta‐analyses of clinical trials, in which placebo response rates in paediatric populations are generally higher than in adult populations.12 The placebo effect observed in IXORA‐PEDS was considerably lower for more stringent endpoints such as PASI 90 (5%) and PASI 100 (2%) at week 12, which was similar to placebo responses observed in adults (PASI 90: UNCOVER‐1, 0·5%; UNCOVER‐2, 0·6%; UNCOVER‐3, 3·1%; PASI 100: UNCOVER‐1, 0%; UNCOVER‐2, 0·6%; UNCOVER‐3, 0%).10, 11

IXE was recently approved by the FDA for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis in patients aged ≥ 6 years and is the first biologic therapy approved for paediatric psoriasis that targets IL‐17A. Other biologic therapies approved for paediatric psoriasis include two tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (etanercept and adalimumab) and the IL‐12/23 antagonist, ustekinumab. PASI 75 was achieved by 57% (week 12) and 58% of patients (week 16) in phase III studies of etanercept (0·8 mg kg−1) and adalimumab (0·8 mg kg−1) for paediatric psoriasis, respectively.13, 14 In adolescent patients (aged 12–17 years) with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis, PASI 75 response at week 12 was achieved by 81% of patients receiving ustekinumab.15

Approved use of these treatments differs across geographies, ages and severities. The FDA approved etanercept and ustekinumab in patients ≥ 4 and ≥ 12 years old, respectively, for moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis but has not approved adalimumab for paediatric psoriasis. The European Medicines Agency approved etanercept and adalimumab in patients with severe psoriasis who are ≥ 6 and ≥ 4 years old, respectively, and ustekinumab for moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis in patients ≥ 6 years old. This study suggests that IXE may be an additional and efficacious treatment option for paediatric patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis.

A strength of IXORA‐PEDS is enrolment of a geographically diverse population. IXE was administered on site during study visits to ensure consistent dosing and administration in paediatric patients. IXE provided consistent efficacy across weight subgroups; however, analysis of patients with baseline weight < 25 kg was limited to a small sample size of three patients. IXE Q4W showed significantly greater skin improvements [PASI 90, PASI 100 and sPGA (0)] compared with etanercept, although this comparison was for patients with severe psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries outside the USA. Limitations of this comparison include a small patient number and the comparison of double‐blind IXE Q4W vs. open‐label etanercept. However, the outcomes assessors were blinded to treatment assignments to minimize potential bias.

In conclusion, IXE provided rapid, statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements over placebo in skin, itch and health‐related quality of life that persisted for up to 48 weeks in paediatric patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. The safety profile of IXE was generally consistent with that in adults with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Thus, IXE may be an additional therapeutic option for moderate‐to‐severe paediatric psoriasis.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 List of IXORA‐PEDS investigators.

Appendix S2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix S3 Study design.

Appendix S4 List of all study endpoints in IXORA‐PEDS.

Appendix S5 Description of efficacy outcomes.

Appendix S6 Additional details regarding safety outcomes.

Appendix S7 Statistical analyses.

Appendix S8 Safety results.

Figure S1 Trial profile for patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Figure S2 Efficacy outcomes in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Table S1 Dosing of study drug through week 48 of IXORA‐PEDS.

Table S2 Number of patients with nonmissing data at each postbaseline visit through Week 48.

Table S3 Baseline demographics and disease characteristics in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Table S4 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and static Physician's Global Assessment responses by weight category.

Table S5 Serious adverse events.

Table S6 Safety through week 12 in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Clinton C. Bertram, PhD, an employee of Eli Lilly and Company, for writing and editorial support.

Appendix 1.

Conflicts of interest. A.S.P. has been an investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Exicure, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, Palvella and Regeneron; and has been a consultant with honoraria from AbbVie, Almirall, Asana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Castle Creek, Dermira, Eli Lilly and Company, Exicure, Forte, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, LifeMax, MEDACorp, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme and Sol‐Gel. M.M.B.S. has received grants from or has been involved in clinical trials with AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, LEO Pharma and Pfizer; and has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, LEO Pharma and Pfizer; fees were paid directly to the institution. G.A.M. has received honoraria and/or grants as a speaker, advisor or investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Cilag, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi Genzyme. J.B. has been a speaker, consultant or investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics and Sun Pharma. A.P. has been an investigator, speaker and/or advisor for AbbVie, Almirall‐Hermal, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Biontec, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, GSK, Hexal, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MC2, Medac, Merck Serono, Mitsubishi, MSD, Novartis, Pascoe, Pfizer, Tigercat Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Schering‐Plough and UCB Pharma. J.C. has been an investigator, speaker, consultant and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Brickell Biotech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, ChemoCentryx, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Janssen, Menlo, Regeneron, Sun Pharma and UCB. S.K., C.R.C., R.G.L., G.G., C.A.L., E.E.H., L.L. and W.X. are employees of and own stock in Eli Lilly and Company. K.P. has received honoraria, grants and/or research funding as a speaker, investigator, advisory board member, data safety monitoring board member and/or consultant for AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, Anacor, Arcutis, Astellas Pharma US, Bausch Health, Baxalta, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Can‐Fite Biopharma, Celgene Corporation, Coherus, Dermira, Dow Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Evelo, Galapagos, Galderma, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Meiji Seika Pharma, Merck (MSD), Merck Serono, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche Laboratories, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda Pharmaceuticals and UCB.

Appendix 2.

Author contributions. A.S.P. contributed to the study design, data acquisition, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. M.M.B.S. and K.P. contributed to data acquisition, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. G.A.M. contributed to the study design, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. J.B. and A.P. contributed to data analysis, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. J.C., G.G., C.A.L. and E.E.H. contributed to data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. S.K., C.R.C. and R.G.L. contributed to the study design, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. L.L. and W.X. contributed to the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors provided approval of the final manuscript for submission and publication.

Funding sources Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation and publication decisions. All authors had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of interest statements are listed in Appendix 1 .

A list of study investigators is provided in Appendix S1 (see Supporting Information).

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. De Jager ME, Van de Kerkhof PC, De Jong EM et al Epidemiology and prescribed treatments in childhood psoriasis: a survey among medical professionals. J Dermatolog Treat 2009; 20:254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB et al Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population‐based study. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:1537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Napolitano M, Megna M, Balato A et al Systemic treatment of pediatric psoriasis: a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016; 6:125–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paller AS, Schenfeld J, Accortt NA et al A retrospective cohort study to evaluate the development of comorbidities, including psychiatric comorbidities, among a pediatric psoriasis population. Pediatr Dermatol 2019; 36:290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR et al Joint American Academy of Dermatology‐National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:161–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bronckers IM, Paller AS, van Geel MJ et al Psoriasis in children and adolescents: diagnosis, management and comorbidities. Paediatr Drugs 2015; 17:373–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cline A, Bartos GJ, Strowd LC et al Biologic treatment options for pediatric psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Children (Basel) 2019; 6:E103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oostveen AM, de Jager ME, van de Kerkhof PC et al The influence of treatments in daily clinical practice on the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index in juvenile psoriasis: a longitudinal study from the Child‐CAPTURE patient registry. Br J Dermatol 2012; 167:145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Geel MJ, Maatkamp M, Oostveen AM et al Comparison of the Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index in assessment of quality of life in patients with psoriasis aged 16–17 years. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA et al Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M et al Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis (UNCOVER‐2 and UNCOVER‐3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet 2015; 386:541–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weimer K, Gulewitsch MD, Schlarb AA et al Placebo effects in children: a review. Pediatr Res 2013; 74:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG et al Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Papp K, Thaci D, Marcoux D et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab every other week versus methotrexate once weekly in children and adolescents with severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390:40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landells I, Marano C, Hsu MC et al Ustekinumab in adolescent patients age 12 to 17 years with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: results of the randomized phase 3 CADMUS study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 List of IXORA‐PEDS investigators.

Appendix S2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix S3 Study design.

Appendix S4 List of all study endpoints in IXORA‐PEDS.

Appendix S5 Description of efficacy outcomes.

Appendix S6 Additional details regarding safety outcomes.

Appendix S7 Statistical analyses.

Appendix S8 Safety results.

Figure S1 Trial profile for patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Figure S2 Efficacy outcomes in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Table S1 Dosing of study drug through week 48 of IXORA‐PEDS.

Table S2 Number of patients with nonmissing data at each postbaseline visit through Week 48.

Table S3 Baseline demographics and disease characteristics in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.

Table S4 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and static Physician's Global Assessment responses by weight category.

Table S5 Serious adverse events.

Table S6 Safety through week 12 in patients with severe paediatric psoriasis in etanercept‐approved countries.