Abstract

Background

Persons with an intellectual disability are at a higher risk of experiencing adversities. The concept of resilience offers promising insights into facilitating personal growth after adversity. The current study aims at providing an overview of the current research on resilience and the way this can contribute to quality of life in people with intellectual disability.

Method

A literature review was conducted in the databases PsycINFO and Web of Science. To evaluate the quality of the studies, the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used.

Results

The themes, autonomy, self‐acceptance and physical health, were identified as internal sources of resilience. External sources of resilience can be found within the social network and daily activities.

Conclusion

The current overview shows promising results to address resilience in adults with intellectual disability. More research is needed to identify the full range of resiliency factors.

Keywords: adulthood, adversity, intellectual disability, resilience

1. INTRODUCTION

Research on resilience as a response to adverse life experiences in people with intellectual disability is still in its infancy (Hollins & Sinason, 2000). Adversity, defined as “a state or instance of serious or continued difficulty or misfortune; a difficult situation or condition; misfortune or tragedy,” requires individuals to make significant or major readjustments (“Adversity”, 2019; Von Lob, Camic, & Clift, 2010). Possibly, people with intellectual disability use different (re)sources to overcome adversities than the general population as a result of divergent developmental trajectories (McCarthy, 2001). The current review aims to identify internal and external sources of resilience in people with intellectual disability.

People with an intellectual disability are at a higher risk of experiencing adversity throughout their entire life (Focht‐New, Clements, Barol, Faulkner, & Service, 2008; Reiter, Bryen, & Shachar, 2007; Vervoort‐Schel et al., 2018). Vervoort‐Schel et al. (2018) found that in children with intellectual disability in residential care, the three most named adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were as follows: parental separation, the mental health problems of a parent and being a witness of violence between parents. To date, it remains unclear whether these ACEs are truly specific for children with intellectual disability or for children referred to institutional care. Adversity during childhood is found to be a significant predictor of physical illness in adults with intellectual disability (Santoro, Shear, & Haber, 2018). Further, ACEs have shown to be more strongly associated with emotional problems, psychiatric and conduct disorders in childhood and adulthood for people with intellectual disability compared to people without intellectual disability (Dekker, Koot, Ende, & Verhulst, 2002; Hatton & Emerson, 2004; Hulbert‐Williams et al., 2014).

In the past decades, research has gone through a major shift in focus concerning the antecedents and consequences of adversity (Masten, 2011). Initially, the focus of research was primarily on the identification of negative consequences after exposure to adverse life experiences. A large number of studies have shown that adverse life events can result in short‐ and long‐term mental and physical health problems such as depression, anxiety and risky behaviours and can consequently result in an increased use of health care (Beards et al., 2013; Bethell, Newacheck, Hawes, & Halfon, 2014; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015; Michl, McLaughlin, Shepherd, & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2013; Tolin, Meunier, Frost, & Steketee, 2010).

In the 1960s, however, researchers started to notice that some children also showed positive adaptations in the aftermath of adversity (Anthony, 1974; Garmezy, 1974; Murphy, 1974; Rutter, 1979). Over the course of life, 80% of all people are exposed to adverse life experiences (Breslau, 2009). Yet, only 10% of these people will develop trauma‐related symptoms such as in post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This leads to the conclusion that many people are able to cope in a positive manner with adversities. The process of adapting to or showing growth after a negative life event is referred to as resilience (Seery, Holman, & Silver, 2010; Tedeschi, Calhoun, & Cann, 2007).

In defining resilience, the terms “adversity” and “positive adaptation” are considered core concepts (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). Masten (2018) defines resilience as the capacity of a system to adapt successfully to challenges that threaten the function, survival or future development of the system. In a review by Windle (2011), resilience is conceptualized as a process of effective negotiating, adapting to or managing significant sources of stress and trauma through assets and resources. Assets and resources can be available within the individual and/or in the environment to support resilience.

Assets are the positive factors and characteristics within a person such as optimism, also referred to as internal sources of resilience. Yeager and Dweck (2012), studying internal sources of resilience, found that students who believed that their intellectual abilities could be developed showed greater achievements in challenging school transitions. This suggests that a “growth” mindset supports resilience. Resources are external sources of resilience provided by family and relationships. For instance, a warm family environment and supportive relationships at home can promote resilience in children after experiencing child maltreatment or bullying (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011; Bowes, Maughan, Caspi, Moffitt, & Arseneault, 2010).

Following the different conceptualizations in literature, three variations of resilience come forward that will be considered in this review: (a) people stay on the same level of functioning even after being exposed to adverse life events (resilience), (b) recovery from adversity (recovery), and (c) growth beyond the original level of functioning (post‐traumatic growth) (Masten, 2018; Windle, 2011). From the conceptualizations of Masten (2018) and Windle (2011), it becomes clear that resilience is a dynamic process and should be observed in the overall context of a system. Some researchers state that resilience should be studied from an ecological perspective including both internal and external sources of resilience (Ungar, 2008, 2011).

A similar combination of factors that results in resilience in one person could have a different outcome in another person. Contextual factors such as the social network, socioeconomic status, community and individual characteristics contribute to the complex nature of resilience (Masten et al., 2004). For instance, a child who has experienced adversity but has a high IQ and social skills is likely to gain support through his interactions with teachers and other children which will further foster positive adaptation (Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, Polo‐Tomas, & Taylor, 2007). In contrast, a child who is struggling in school and who is aggressive and uncooperative is more likely to be rejected by peers and adults, thereby increasing its risk towards persistent maladaptation. Through maladaptive behaviour, these children are at risk of developing a small social network with less supportive persons. Since children with intellectual disability often struggle with academic achievements and are at a higher risk of showing maladaptive behaviour, these children are also at a higher risk of lacking external sources of resilience in adulthood.

A positive transition into adulthood is considered to facilitate resilience after experiencing adversity in childhood (Masten, Obradović, & Burt, 2006). When transitioning into adulthood, emerging adults with intellectual disability experience more stress compared to their non‐disabled peers (Forte, Jahoda, & Dagnan, 2011). When a person with intellectual disability leaves school and fails to find a suitable work environment, there is a risk of social isolation (Hall, 2009). Good cognitive skills and executive functioning, self‐efficacy economical security and close relationships to peers, family and mentors can help to be resilient in emerging adulthood (Burt & Paysnick, 2012). These factors can be limited or under stress for adults with intellectual disability. The maintenance of supportive relationships requires a degree of social–emotional functioning which is generally underdeveloped in people with intellectual disability (Alloway, 2010; Nord, Luecking, Mank, Kiernan, & Wray, 2013). The social network of adults with intellectual disability are found to be much smaller compared to adults in the general population, whereas in some studies, it is shown that sources of resilience often can be found in the social network (Forrester‐Jones et al., 2006; Jahoda & Pownall, 2014; Verdonschot, De Witte, Reichrath, Buntinx, & Curfs, 2009).

More research on resilience in adults is needed to promote resilience in people with intellectual disability. To date, there is no overview of research available regarding resilience factors in individuals with intellectual disability. The current study aims to provide an overview of research about resilience in people with intellectual disability. The main research question was as follows: “What is known in research about resilience in adults with intellectual disability?”. In the current study, the focus is on the perspective of adults with intellectual disability to provide a first insight in the experience of adults with intellectual disability with regard to resilience. In providing an overview on the literature on resilience in people with intellectual disability, we also compared the definitions of adversity and resilience among the various studies. Finally, themes related to resilience from the perspective of adults with intellectual disability are mentioned.

2. METHOD

A systematic literature review was performed following different stages (Clarke, 2001; Harden & Thomas, 2005). First, a comprehensive search was performed in the databases of PsycINFO and Web of Science. To be included in the current systematic literature review, different inclusion and exclusion criteria were used. The sample of the study needed to consist of adults with intellectual disability: participants below the age of 18 were excluded. Further, no restrictions on the level of intellectual disability were applied. The concept of resilience was the main focus of the study, when a definition of resilience was missing the study was excluded. The study needed to be published in English. Full text needed to be available to be included in the current review. No editorial studies were included. Finally, studies focusing on the perspective of the social network instead of the perspective of the adult with intellectual disability were excluded.

For the concept of intellectual disability, the following terms were used: intellectual development disorder* OR mental retard* OR mental* deficien* OR slow learner* OR general learning disabilit* OR intellectual* disab*. These search terms were combined for both databases with: AND resilien* NOT (child* OR parent* OR adolesc* OR youth OR young OR teen*). Resilience is a relatively new concept in psychology and has only been used since the 1960s. As a result, we have only searched for studies and manuscripts that were published in the period between 1960 and 2019 (Masten & Reed, 2002). Database limitations were set on adulthood (18 years and older).

Second, to analyse the different themes in the selected research, a narrative approach was adopted (Booth, Sutton, & Papaioannou, 2016). Step 1 included the search for abstracts. In step 2, the studies were selected for detailed reading, while in step 3 summaries were made of all studies included in the review. Finally, in step 4 recurring themes were identified from the included studies. To evaluate the quality of the studies, the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pluye et al., 2011) was used to describe the methodological quality for three domains: qualitative, quantitative and mixed‐method. Based on the number of criteria used, a percentage was given on the quality of the described methodology. Table 1 presents an overview of the percentages.

Table 1.

Descriptives of all studies included in the literature review

| Authors | Year | Design | MMAT | Type | Sample size | Average age | Range | Gender | Levela | Resilienceb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clarke, Camilleri & Goding | 2015 | Case reports | 75% | Qualitative | 6 | Unknown | 36–70 | M/F | Unknown | 3 |

| 2 | Conder, Mirfin‐Veitch & Gates | 2015 | Case reports | 75% | Qualitative | 25 | Unknown | 21–65 | F | Unknown | 1,2 |

| 3 | Dew, Llewellyn & Gorman | 2006 | Case reports | 75% | Qualitative | 13 | 68 | 55–82 | F | Mild | 2,3 |

| 4 | Mannino | 2015 | Case reports | 67% | Mixed‐method | 31 | Unknown | 18–26 | M/F | Unknown | 3 |

| 5 | Starke | 2013 | Case reports | 67% | Mixed‐method | 10 | 23.3 | 18–32 | M/F | Unknown | 1,2,3 |

| 6 | Taggart, McMillan & Lawson | 2009 | Case reports | 75% | Qualitative | 12 | 51.1 | 28–64 | F | Mild to moderate | 2,3 |

Subnote: “Level” reflects the level of functioning of the participants with intellectual disability, ranging from borderline intellectual functioning to profound intellectual disability.

Subnote: “Resilience” shows whether a conceptualization of resilience is present: 0 = a clear conceptualization of resilience is missing, (1 = people stay on the same level of functioning even after being exposed to adverse life events (resilience), 2 = recovery from adversity (recovery), and 3 = growth beyond the original level of functioning (post‐traumatic growth).

For every study, the main aim was to understand which factors contributed to resilience in people with intellectual disability. In the coding scheme, different types of information were coded: general study information, sample descriptors and the conceptualization of variables such as adversity and resilience. The themes related to resilience were synthesized, overlapping themes were combined, or new overarching themes were established. The classification and assessment of intellectual disability were coded as well as the level of operationalization of the concept of resilience. To objectify the process of analysing the recurring themes, two trained research assistants rated the selected studies. Interrater reliability varied from 0.871 to 0.953 which can be considered as excellent. Differences in coding were resolved through discussion, until agreement was obtained.

3. RESULTS

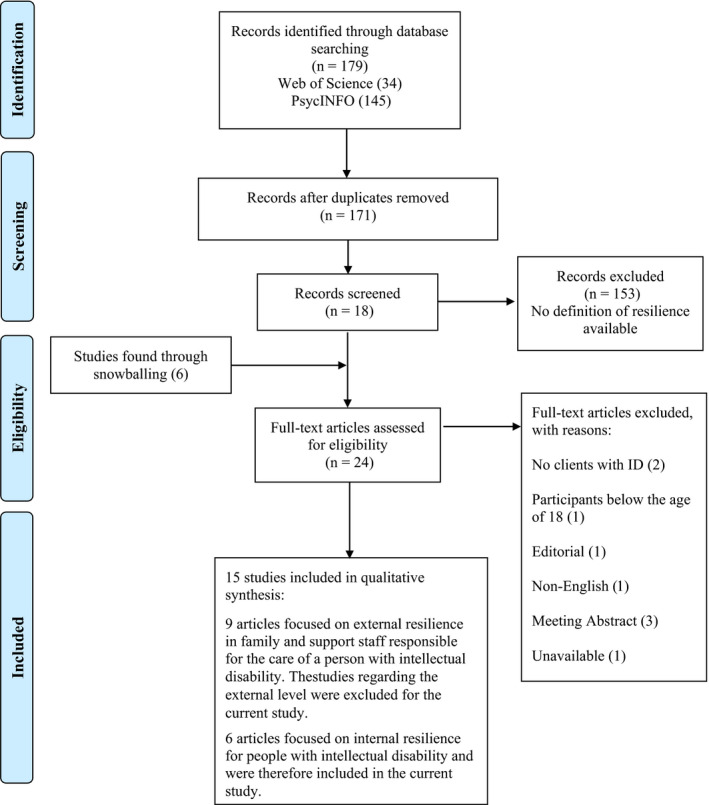

The databases PsycINFO (1960–2019) and Web of Science (1975–2019) were searched. A total of 179 studies were found when combining the search terms. Eight duplicates were removed. After exclusion of studies not addressing resilience, a total of 18 studies remained. Exclusion of studies based on the inclusion criteria was done by the first author in consultation with the co‐authors. Manual searches in reference lists of relevant studies were conducted to identify other studies, and 6 new studies were identified. Thus, 24 studies were found eligible for further inspection. After checking the titles and abstracts, nine more studies were excluded based on the inclusion criteria. Studies that did not include clients with intellectual disability (2) or included participants younger than 18 years of age (1) were excluded. Meeting abstracts for conferences were excluded (3). One study was an editorial note for a special issue of a journal regarding resilience in people with intellectual disability and was therefore excluded as well. Also, one non‐english study was excluded. Finally, one study was not available in the databases consulted. Fifteen studies remained, nine focusing on promoting resilience in the formal and informal social network. Since the current study focuses on promoting resilience in adults with intellectual disability, these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were disregarded. Finally, six studies were identified for the current literature review focusing on resilience in adults with intellectual disability. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of the search strategy. The PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009) were followed in performing the review and construction of the flow chart.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search strategy following PRISMA 2009 (Moher et al., 2009)

3.1. Characteristics of the studies

Table 2 presents an overview of the selected research studies. All studies were case reports with a qualitative (4) or mixed‐method (2) research design and were published between 2006 and 2015. The sample sizes ranged from 6 to 31 participants. The average age of the participants was not always mentioned; however, every study did mention an age range. The ages ranged from 18 to 82 years. Three studies included both women and men, and the other three studies solely focused on women. The level of severity of the intellectual disability was only reported in two studies, varying from mild to moderate intellectual disability. In the other four studies, the level of functioning of the participants with intellectual disability was not mentioned. Information about the method to assess intellectual disability was missing in all studies. None of the studies mentioned inclusion of people with borderline intellectual functioning.

Table 2.

Overview of resiliency factors for each study

| Authors | Autonomy | Acceptance and perseverance | Physical health | Supportive social network | Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clarke, Camilleri & Goding | X | X | |||

| 2 | Conder, Mirfin‐Veitch & Gates | X | X | X | ||

| 3 | Dew, Llewellyn & Gorman | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4 | Mannino | X | X | |||

| 5 | Starke | X | X | X | ||

| 6 | Taggart, McMillan & Lawson | X | X | X |

3.2. Conceptualization of adversity

Adversity was not clearly conceptualized in any of the studies. The study of Conder, Mirfin‐Veitch, and Gates (2015) defined adversity as “being mentally unwell.” In the study of Dew, Llewellyn, and Gorman (2006), examples of adverse life events were given, but no clear definition was adopted. For example, the loss of loved ones or the need to move to a different home was discussed as significant adverse life events in the lives of the participants. No standardized instruments were used in any of the studies to identify the concept of adversity or of adverse life events. The study of Taggart, Mcmillan, and Lawson (2009) did include questions about adverse life events in the semi‐structured interviews with regard to the mental health of the participants. Examples of events mentioned by the participants were among others: the death of the mother or partner, being bullied, sexual abuse, miscarriages and the out‐of‐home placement of children. Most participants experienced more than one adverse life event.

3.3. Conceptualization of resilience

In the selected studies, several concepts of resilience, recovery and post‐traumatic growth were used as follows: (a) people stay on the same level of functioning even after being exposed to adverse life events (resilience), (b) recovery from adversity (recovery), and (c) growth beyond the original level of functioning (post‐traumatic growth) (Masten, 2018; Windle, 2011). Some studies applied more than one of these concepts but no study discussed all three conceptualizations. Resilience was described as people functioning on the same level in the studies of Conder et al. (2015) and Taggart et al. (2009). Recovery was applied in the studies of Conder et al. (2015) and Dew et al. (2006). The concept of post‐traumatic growth was discussed in five out of six studies (Clarke, Camilleri, & Goding, 2015; Dew et al., 2006; Mannino, 2015; Starke, 2013; Taggart et al., 2009). Even though post‐traumatic growth was conceptualized in most studies, no assessment procedures were described.

3.3.1. Internal sources of resilience

The data revealed different recurring themes on internal sources of resilience. A wide variety of factors was identified that were categorized into three themes: “autonomy,” “self‐acceptance” and “physical health.” In Table 2, an overview of the different factors regarding internal sources of resilience is presented.

Autonomy was closely linked to well‐being, and the theme autonomy was mentioned in four out of six studies. In the study of Conder et al. (2015), women expressed that their feelings of happiness were strongly linked to their ability to make independent decisions. These women felt included in society and that they were in control of their own lives. The women were not fully independent, but they were able to take care of themselves adequately in the protected home they were living in. Dew et al. (2006), also studying resilience in women, found that managing money was a very important topic with regard to feeling in control and thus feeling more autonomous. In daily life, the women received an allowance that they could spend on groceries and small purchases. The larger expenses such as rent and other monthly charges were managed by professional caregivers or family. Even though the women were living in protected homes, they each lived in their own apartment and were able to engage in activities of their choice. In sum, the results imply that despite dependency from care, it is very important to give individuals opportunities that fit their skills and capacities to take control over their own lives as much as possible.

In the study of Clarke et al. (2015), it is suggested that people with intellectual disability can build resilience through the membership of a self‐advocacy group. By taking different opportunities in a self‐advocacy group, a person with intellectual disability can learn how to speak up, make choices and develop other self‐determination skills. These skills led to higher levels of autonomy and positive outcomes of well‐being. The results in this study suggest that enforcing control and autonomy should go beyond merely offering choices and additionally focus on involving people with intellectual disability in the process of constructing choices. In the study of Starke (2013), autonomy was not identified in the results as a specific theme. However, in the stories of the adults “feeling in control” was frequently mentioned. The authors suggest that for adults the process of resilience was reinforced through feelings of control. This was illustrated by a greater desire of being listened to and being given information about the services and processes influencing their everyday life. In sum, by strengthening autonomy, the person with intellectual disability will gain a sense of control and is able to be the director of his own life.

Self‐acceptance is a theme operationalized by Dew et al. (2006) and Mannino (2015). Dew et al. (2006) mention the theme “It's just who I am,” reflecting an attitude of self‐acceptance. The women in the study of Dew et al. (2006) embraced their limitations and dependency on care, enabling them to accept their situation and accepting themselves as a person. The results further suggest that acceptance of yourself as a whole person with challenges and strengths can lead to a positive attitude enabling persons with intellectual disability to face their future with a positive outlook.

Despite misfortune and other challenges, emerging adults with intellectual disability employing an accepting attitude were able to push through adversity (Mannino, 2015). The author named the theme “Life is a journey,” by suggesting that adults who accept challenges as a part of life are better capable to adapt to adversity. When a person is able to accept his or her weaknesses, this person is also able to ask for help and find the right support to deal with challenges in life (Mannino, 2015).

Physical health was identified in the studies of Dew et al. (2006) and Taggart et al. (2009) in which women with intellectual disability were interviewed about resilience. In both studies, the women noted the importance of physical health. Feeling healthy was important to the women, and they had regular contact with a physician and the dentist and used preventive services such as a mammography. In the study of Dew et al. (2006), only two of thirteen women mentioned their health preventing them to do what they wanted. All women were supported by professionals or an informal network to access medical services (Dew et al., 2006).

Taking medication regularly was part of the theme physical health, not all women understood why they used prescribed medications. All women did understand they needed the medication to stay well in general. The medication had psychological or medical benefits, and the women were supported by staff to take these pills on time (Taggart et al., 2009). Also, physical activities such as walking helped the women to increase their mood and feel happy. Another aspect of physical health the women pointed out was eating healthy for which they also depended on staff (Taggart et al., 2009).

3.3.2. External sources of resilience

In all studies, special attention was devoted to external sources of resilience, see Table 2 for an overview. Overall, there seems to be more consensus on external sources of resilience. Two themes were identified as follows: “a supportive social network” and “daily activities.” In all studies, the influence of external sources next to internal sources of resilience was discussed, but no quantitative measures were made available. Different studies suggested that internal sources of resilience were reinforced by external sources leading to positive growth. (Dew et al., 2006; Starke, 2013).

A supportive social network was operationalized as having qualitative close relationships to offer support. In five out of six studies, the importance of family and friends was mentioned. The importance of support from professional caregivers was emphasized next to the support of the informal support network. In all studies, people with intellectual disability mention the importance of professional caregivers. In most studies, the importance of the relationship with family and friends was equally valued compared to the relationship with professional caregivers. Professional caregivers seemed to have a large influence and were more often involved in the lives of people with intellectual disability compared to friends of the same age (Dew et al., 2006; Starke, 2013). In the study of Conder et al. (2015) also, romantic relationships and relationships with their own children were mentioned. The women with intellectual disability in this study seemed to focus mainly on current relationships. At an older age, it seemed that people with intellectual disability start to worry about their well‐being when parents and siblings passed away (Conder et al., 2015). For these people, it seemed difficult to establish new relationships, and there were limited opportunities to meet new people, except when a facility or community hosted regular activities.

Most participants in the studies were living in residential care facilities, had regular contact with professional caregivers and were able to engage in leisure activities with other residents. In a structured setting, people with intellectual disability seemed to be better able to establish relationships under the supervision and guidance of professional caregivers. In the study of Starke (2013), the themes “supportive social network” and “autonomy” were therefore intertwined. Participants who described their family as a source of life satisfaction also told the researchers that their family supported them in becoming more independent.

Daily activities, such as handicrafts, taking walks or playing games, were viewed in five out of six studies as a significant factor in facilitating resilience. Engaging in daily activities had various positive outcomes, such as a clear daily structure and providing the people with intellectual disability with a sense of safety through predictability (Taggart et al., 2009). Further, daily activities gave the people with intellectual disability a sense of belonging to the community (Dew et al., 2006). Clarke et al. (2015) suggest that being part of a self‐advocacy group provides people with intellectual disability with opportunities to develop social–emotional skills. Within the advocacy group, people with intellectual disability were challenged, for instance, in how they could regulate their emotions and how to speak up about their personal wishes and desires. Generally, the daily activities were organized and structured by people in the personal or professional support network. By engaging in regular activities, also opportunities arose for interaction with others to establish and maintain social relationships. Since finding appropriate work is often a challenge for people with intellectual disability, most activities involved leisure activities (Conder et al., 2015). In the study of Conder et al. (2015), it was suggested that “keeping busy” was an important factor in protecting the mental health of women with intellectual disability. These women were able to participate in arranged activities at the day centre; the more independent women also chose activities for themselves like different crafts such as knitting and painting. In contrast, in the study of Starke (2013), it was shown that there were great differences in the type of activities emerging adults participated in. Some emerging adults had clearly defined daily structures, and some met their friends on occasion and did not participate in specific structured leisure activities.

4. DISCUSSION

The current systematic literature review aims at providing an overview of the research on resilience in adults with intellectual disability. It becomes notable that research on resilience in adults with intellectual disability is still very limited. Masten and Reed (2002) showed that research on resilience started in the 1960s. However, research on resilience in people with intellectual disability can only be found from 2006 to date. This finding is striking since people with intellectual disability are at a higher risk of experiencing adversity (Focht‐New et al., 2008; Reiter et al., 2007; Vervoort‐Schel et al., 2018) but resilience can be a buffer to diminish negative effects. In our study, a distinction is made between internal and external sources of resilience. Themes identified regarding internal sources of resilience were autonomy, self‐acceptance and physical health. In the selected studies, the influence of external sources of resilience was emphasized. Themes identified on external sources were supportive social network and daily activities.

Regarding internal sources of resilience, the themes, autonomy, self‐acceptance and physical health, were found to contribute to resilience in people with intellectual disability. Since many people with intellectual disability depend on professional care, enhancing autonomy can be specifically challenging. A supportive network should promote independency appropriate to the capacities of a person. Also, research shows that it is important for a person to show self‐acceptance as a source of resilience. This could enable a person to push through after experiencing adversity. In the review of Linley and Joseph (2004) on resilience in the general population, it was shown that people who were able to have an accepting coping style also showed higher levels of growth in the aftermath of trauma and adversity. People with intellectual disability are at risk of experiencing social exclusion because they are often seen as different throughout their entire life (Hall, 2009). It can be hypothesized that through social exclusion and a greater dependency on social networks, combined with limited learning skills, people with intellectual disability will have more difficulty developing self‐acceptance. This requires special attention of professionals to help people with intellectual disability to acquire a realistic and accepting coping style. Finally, physical health is seen as an important factor with regard to resilience. In the selected studies, most persons were living in residential care or had people to support them in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. There was no information about the actual physical well‐being of the people with intellectual disability involved in the studies selected. Thus, it is still unclear how physical activity and medication are related to overcoming an adverse experience. It is hypothesized that medication compliance for instance is important to achieve emotional and physical stability allowing these persons to participate in physical activities. Future research should address all three themes, autonomy, self‐acceptance and physical health, to better understand the underlying mechanisms with regard to resilience.

There seems to be a dynamic connection between internal and external sources of resilience as suggested in previous research (Jaffee et al., 2007; Ungar, 2008). External sources of resilience are as follows: a social network and activities. External sources can facilitate internal sources resulting in a dynamic process of resilience. To establish and maintain stable relationships within the social network, persons with intellectual disability are more dependent on the people who support them (Bigby, 2008; Guralnick, 2006). However because of problems with emotion regulation and perspective taking, people with intellectual disability experience more conflicts in relationships (Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2014; Van Nieuwenhuijzen, Orobio De Castro, & Van Aken, 2009). Having limited communication skills restricts the ability to deal with these conflicts. Additionally, as people with intellectual disability follow a different trajectory regarding socio‐emotional development, people with intellectual disability also tend to have poorer social skills (Došen, 2005a, 2005b). Because of limited socio‐emotional skills, small and sometimes unsupportive social support networks in people with intellectual disability, their capacity to develop resilience could be hampered. Through organized daily activities, it is possible to enlarge the social network. Daily activities have the capacity to promote a positive self‐image and provide a clear daily routine. Nevertheless, to engage in these daily activities people with intellectual disability are also dependent on their social network, family or professional caregivers. Future research should focus on resilience by applying a systemic research model and on exploring how to reinforce the positive influence of external sources of resilience in people with intellectual disability.

In the general population, by applying the broaden‐and‐build theory, positive emotions can contribute to the process of resilience (Fredrickson, 2013). The broaden‐and‐build theory states that people who express more positive emotions experience a wider range of thoughts and actions and are more aware of options compared to people that express a more negative or neutral state of mind. People who express more positive emotions explore and play more, by gaining experience these people will be better equipped when faced with adversity. Children with intellectual disability play and explore less showing a more passive state compared to children in the general population (Goodman & Linn, 2003). These children are missing opportunities to learn and need more stimulation from their environment to gain experience and build resources of resilience, leading to the limited availability of resources for resilience in adulthood. Research shows that parents of children with intellectual disability can experience negative emotions concerning the interaction with their disabled child (Boström, Broberg, & Hwang, 2010). Other children's attitudes towards children with a disability can be negatively biased as well (Doody, Hastings, O’Neill, & Grey, 2010; Nowicki & Sandieson, 2002). This can all hamper the stimulation of positive emotions and resilience throughout the whole life of people with intellectual disability. Currently, research on the development of positive emotions in people with intellectual disability is scarce. More research is needed to understand whether knowledge about stimulating resilience in the general population can also be applied in people with intellectual disability.

Several limitations should be mentioned regarding the current study. First, only case reports were found thus limiting the generalizability of the results. However, qualitative research on people with intellectual disability is necessary when there is unsufficient specificity regarding the hypothesis (Beail & Williams, 2014; McVilly, Stancliffe, Parmenter, & Burton‐Smith, 2008) and can provide valuable information for future research. Second, none of the included studies scored positively on all the criteria of the MMAT, and percentages ranged from 67 to 75 per cent (Pluye et al., 2011). For the qualitative studies, none of the studies scored positively on the criterium regarding the notion of reflexivity. No information was given on the influence of the role and/or perspective of the researcher and possible interactions with the participants. In the studies with a mixed‐method design, none of the studies reported the limitations associated with the integration of qualitative and quantitative results. Finally, the population of people with intellectual disability included in the selected studies was diverse, with different levels of intellectual functioning and living in different circumstances. The participants in the studies included functioned on mild to moderate levels of intelligence and were living in protected homes, where professional caregivers monitored their behaviour and supported them to increase their quality of life. The results should thus be mainly understood within these contexts.

In the current study, three different pathways of resilience were presented as follows: (a) people stay on the same level of functioning even after being exposed to adverse life events (resilience), (b) recovery from adversity (recovery), and (c) growth beyond the original level of functioning (post‐traumatic growth) (Masten, 2018; Windle, 2011). To better understand resilience in people with intellectual disability in future studies, the occurrence of all three pathway(s) should be researched based on a clear operationalization of resilience measured over longer periods of time. Future research should focus on developing a theoretical framework regarding to the concepts of adversity and resilience and the relation between these concepts.

People with intellectual disability are often excluded from participation in research, while research has the potential to enhance positive change (Feldman, Bosett, Collet, & Burnham‐Riosa, 2014; Lai, Elliott, & Ouellette‐Kuntz, 2006). The perspective of people with intellectual disability is often neglected in scientific research due to limitations in design or methods (Mactavish, Mahon, & Lutfiyya, 2000). In the study of Fujiura and the RRTC Expert Panel on Health Measurement (2012) on physical health, limitations regarding self‐report measures in people with intellectual disability are addressed. The authors suggest that the perspective in research should be as follows: “What can we learn from the experiences of people with intellectual disability.” Through research, it is possible to voice the opinion of people with intellectual disability, which has been neglected for many years in research (Feldman et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2006). In most studies regarding people with intellectual disability, participants are defined by their level of intellectual functioning underlining people with mild intellectual disability (IQ scores ranging between 50 and 70) (Peltopuro, Ahonen, Kaartinen, Seppälä, & Närhi, 2014) while in the DSM 5 intelligence is no longer seen as the deciding factor for the classification of the severity of intellectual disability (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Wieland & Zitman, 2016). In future research on resilience, more attention should also be given to persons with decreased levels of adaptive functioning (Alloway, 2010; Greenspan, 2017).

In sum, the importance of addressing resilience in people with intellectual disability is stressed, but more high‐quality research is needed to fully understand all aspects of resilience in order to enhance the quality of life of people with intellectual disability.

Scheffers F, van Vugt E, Moonen X. Resilience in the face of adversity in adults with an intellectual disability: A literature review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33:828–838. 10.1111/jar.12720

Funding information

The current research was funded by two foundations: MEE ZHN (a non‐governmental organization for people with disabilities) and VCVGZ (a foundation that finances research promoting mental health care)

REFERENCES

Studies selected in the systematic literature review are marked with an asterisk.

- Adversity (2019). Merriam‐Webster’s online dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.merriam‐webster.com/dictionary/adversity [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, T. O. , & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 266–272. 10.1177/070674371105600505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, T. P. (2010). Working memory and executive function profiles of individuals with borderline intellectual functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(5), 448–456. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. BMC Medicine, 17, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, E. J. (1974). The syndrome of the psychologically invulnerable child In Anthony E. J. & Koupernik C. (Eds.), The child in his family: Children at psychiatric risk (pp. 529–545). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Beail, N. , & Williams, K. (2014). Using qualitative methods in research with people who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 85–96. 10.1111/jar.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beards, S. , Gayer‐Anderson, C. , Borges, S. , Dewey, M. E. , Fisher, H. L. , & Morgan, C. (2013). Life events and psychosis: A review and meta‐analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(4), 740–747. 10.1093/schbul/sbt065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, C. D. , Newacheck, P. , Hawes, E. , & Halfon, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106–2115. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigby, C. (2008). Known well by no‐one: Trends in the informal social networks of middle‐aged and older people with intellectual disability five years after moving to the community. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 33(2), 148–157. 10.1080/13668250802094141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A. , Sutton, A. , & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, P. K. , Broberg, M. , & Hwang, P. (2010). Parents' descriptions and experiences of young children recently diagnosed with intellectual disability. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(1), 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes, L. , Maughan, B. , Caspi, A. , Moffitt, T. E. , & Arseneault, L. (2010). Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: Evidence of an environmental effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(7), 809–817. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau, N. (2009). The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(3), 198–210. 10.1177/1524838009334448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt, K. B. , & Paysnick, A. A. (2012). Resilience in the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 493–505. 10.1017/S0954579412000119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, M. (2001). Cochrane reviewers handbook 4.1. 4. London, UK: The Cochrane Library. [Google Scholar]

- *Clarke, R. , Camilleri, K. , & Goding, L. (2015). What’s in it for me? The meaning of involvement in a self‐advocacy group for six people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19(3), 230–250. 10.1177/1744629515571646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Conder, J. A. , Mirfin‐Veitch, B. F. , & Gates, S. (2015). Risk and resilience factors in the mental health and well‐being of women with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(6), 572–583. 10.1111/jar.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, M. C. , Koot, H. M. , Ende, J. V. D. , & Verhulst, F. C. (2002). Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(8), 1087–1098. 10.1111/1469-7610.00235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dew, A. , Llewellyn, G. , & Gorman, J. (2006). “Having the time of my life”: An exploratory study of women with intellectual disability growing older. Health Care for Women International, 27(10), 908–929. 10.1080/07399330600880541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody, M. A. , Hastings, R. P. , O’Neill, S. , & Grey, I. M. (2010). Sibling relationships in adults who have siblings with or without intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 224–231. 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Došen, A. (2005a). Applying the developmental perspective in the psychiatric assessment and diagnosis of people with intellectual disability: Part I assessment. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Došen, A. (2005b). Applying the developmental perspective in the psychiatric assessment and diagnosis of people with intellectual disability: Part II diagnosis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M. A. , Bosett, J. , Collet, C. , & Burnham‐Riosa, P. (2014). Where are persons with intellectual disabilities in medical research? A survey of published clinical trials. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(9), 800–809. 10.1111/jir.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, D. , & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Focht‐New, G. , Clements, P. T. , Barol, B. , Faulkner, M. J. , & Service, K. P. (2008). People with developmental disabilities exposed to interpersonal violence and crime: Strategies and guidance for assessment. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44(1), 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester‐Jones, R. , Carpenter, J. , Coolen‐Schrijner, P. , Cambridge, P. , Tate, A. , Beecham, J. , … Wooff, D. (2006). The social networks of people with intellectual disability living in the community 12 years after resettlement from long‐stay hospitals. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, M. , Jahoda, A. , & Dagnan, D. (2011). An anxious time? Exploring the nature of worries experienced by young people with a mild to moderate intellectual disability as they make the transition to adulthood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50(4), 398–411. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2010.02002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47(1), 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiura, G. T. , & RRTC Expert Panel on Health Measurement (2012). Self‐reported health of people with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(4), 352–369. 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy, N. (1974). The study of competence in children at risk for severe psychopathology In Anthony E. J. & Koupernik C. (Eds.), The child in his family: Children at psychiatric risk (pp. 77–97). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, L. , & Cuskelly, M. (2014). Vulnerability to loneliness in people with intellectual disability: An explanatory model. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(3), 192–199. 10.1111/jppi.12089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, J. F. , & Linn, M. I. (2003). " Maladaptive" behaviours in the young child with intellectual disabilities: A reconsideration. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 50(2), 137–148. 10.1080/1034912032000089648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan, S. (2017). Borderline intellectual functioning: An update. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(2), 113–122. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick, M. J. (2006). Peer relationships and the mental health of young children with intellectual delays. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 3(1), 49–56. 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. A. (2009). The social inclusion of people with disabilities: A qualitative meta‐analysis. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 3(3), 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, A. , & Thomas, J. (2005). Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(3), 257–271. 10.1080/13645570500155078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, C. , & Emerson, E. (2004). The relationship between life events and psychopathology amongst children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(2), 109–117. 10.1111/j.1360-2322.2004.00188.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins, S. , & Sinason, V. (2000). Psychotherapy, learning disabilities and trauma: New perspectives. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(1), 32–36. 10.1192/bjp.176.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert‐Williams, L. , Hastings, R. , Owen, D. M. , Burns, L. , Day, J. , Mulligan, J. , & Noone, S. J. (2014). Exposure to life events as a risk factor for psychological problems in adults with intellectual disabilities: A longitudinal design. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(1), 48–60. 10.1111/jir.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, S. R. , Caspi, A. , Moffitt, T. E. , Polo‐Tomas, M. , & Taylor, A. (2007). Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non‐resilient maltreated children: A cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(3), 231–253. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda, A. , & Pownall, J. (2014). Sexual understanding, sources of information and social networks; the reports of young people with intellectual disabilities and their non‐disabled peers. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(5), 430–441. 10.1111/jir.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis, K. A. , & Chandler, G. E. (2015). Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(8), 457–465. 10.1002/2327-6924.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, R. , Elliott, D. , & Ouellette‐Kuntz, H. (2006). Attitudes of research ethics committee members toward individuals with intellectual disabilities: The need for more research. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 3(2), 114–118. 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00062.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linley, P. A. , & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 17(1), 11–21. 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mactavish, J. B. , Mahon, M. J. , & Lutfiyya, Z. M. (2000). “I can speak for myself”: Involving individuals with intellectual disabilities as research participants. Mental Retardation, 38(3), 216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mannino, J. E. (2015). Resilience and transitioning to adulthood among emerging adults with disabilities. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(5), e131–e145. 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. (2011). Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 493–506. 10.1017/S0954579411000198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory Review, 10, 12–31. 10.1111/jftr.12255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , Burt, K. B. , Roisman, G. I. , Obradović, J. , Long, J. D. , & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. 10.1017/S0954579404040143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , Obradović, J. , & Burt, K. B. (2006). Resilience in emerging adulthood: Developmental perspectives on continuity and transformation In Arnett J. J. & Tanner J. L. (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 173–190). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , & Reed, M. G. J. (2002). Resilience in development. Handbook of Positive Psychology, 74, 88. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J. (2001). Post‐traumatic stress disorder in people with learning disability. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 163–169. 10.1192/apt.7.3.163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McVilly, K. R. , Stancliffe, R. J. , Parmenter, T. R. , & Burton‐Smith, R. M. (2008). Remaining open to quantitative, qualitative, and mixed‐method designs: An unscientific compromise, or good research practice? International Review of Research in Mental Retardation, 35, 151–203. [Google Scholar]

- Michl, L. C. , McLaughlin, K. A. , Shepherd, K. , & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2013). Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(2), 339 10.1037/a0031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. , & The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L. B. (1974). Coping, vulnerability, and resilience in childhood In Coelho G. V., Hamburg D. A., & Adams J. E. (Eds.), Coping and adaptation (pp. 69–100). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, D. , Luecking, R. , Mank, D. , Kiernan, W. , & Wray, C. (2013). The state of the science of employment and economic self‐sufficiency for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(5), 376–384. 10.1352/1934-9556-51.5.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, E. A. , & Sandieson, R. (2002). A meta‐analysis of school‐age children's attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 49(3), 243–265. 10.1080/1034912022000007270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peltopuro, M. , Ahonen, T. , Kaartinen, J. , Seppälä, H. , & Närhi, V. (2014). Borderline intellectual functioning: A systematic literature review. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 52(6), 419–443. 10.1352/1934-9556-52.6.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye, P. , Robert, E. , Cargo, M. , Bartlett, G. , O’Cathain, A. , Griffiths, F. , … Rousseau, M. C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved from . Archived by WebCite® at http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.comhttp://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, S. , Bryen, D. N. , & Shachar, I. (2007). Adolescents with intellectual disabilities as victims of abuse. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 11(4), 371–387. 10.1177/1744629507084602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (1979). Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage In Kent M. W. & Rolf J. E. (Eds.), Primary prevention of psychopathology: Social competence in children (pp. 49–74). Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, A. F. , Shear, S. M. , & Haber, A. (2018). Childhood adversity, health and quality of life in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(10), 854–863. 10.1111/jir.12540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seery, M. D. , Holman, E. A. , & Silver, R. C. (2010). Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(6), 1025 10.1037/a0021344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Starke, M. (2013). Everyday life of young adults with intellectual disabilities: Inclusionary and exclusionary processes among young adults of parents with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 164–175. 10.1352/1934-9556-51.3.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Taggart, L. , McMillan, R. , & Lawson, A. (2009). Listening to women with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems: A focus on risk and resilient factors. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 13(4), 321–340. 10.1177/1744629509353239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R. G. , Calhoun, L. G. , & Cann, A. (2007). Evaluating resource gain: Understanding and misunderstanding posttraumatic growth. Applied Psychology, 56(3), 396–406. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00299.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin, D. F. , Meunier, S. A. , Frost, R. O. , & Steketee, G. (2010). Course of compulsive hoarding and its relationship to life events. Depression and Anxiety, 27(9), 829–838. 10.1002/da.20684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. The British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 218–235. 10.1093/bjsw/bcl343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. (2011). The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), 1 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nieuwenhuijzen, M. , Orobio de Castro, B. , Van Aken, M. A. G. , & Matthys, W. (2009). Impulse control and aggressive response generation as predictors of aggressive behaviour in children with mild intellectual disabilities and borderline intelligence. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(3), 233–242. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonschot, M. M. , De Witte, L. P. , Reichrath, E. , Buntinx, W. H. E. , & Curfs, L. M. (2009). Community participation of people with an intellectual disability: A review of empirical findings. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(4), 303–318. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort‐Schel, J. , Mercera, G. , Wissink, I. , Mink, E. , Van der Helm, P. , Lindauer, R. , & Moonen, X. (2018). Adverse Childhood Experiences in children with intellectual disabilities: An exploratory case‐file study in Dutch residential care. International Journal of Systematic Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2136 10.3390/ijerph15102136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Lob, G. , Camic, P. , & Clift, S. (2010). The use of singing in a group as a response to adverse life events. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 12(3), 45–53. 10.1080/14623730.2010.9721818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, J. , & Zitman, F. G. (2016). It is time to bring borderline intellectual functioning back into the main fold of classification systems. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(4), 204–206. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.051490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle, G. (2011). What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 21(2), 152–169. 10.1017/S0959259810000420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D. S. , & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. 10.1080/00461520.2012.722805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]