Abstract

Rituximab‐containing induction followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard first‐line treatment for young mantle cell lymphoma patients. However, most patients relapse after ASCT. We investigated in a randomised phase II study the outcome of a chemo‐immuno regimen and ASCT with or without maintenance therapy with bortezomib. Induction consisted of three cycles R‐CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), two cycles high‐dose cytarabine, BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) and ASCT. Patients responding were randomised between bortezomib maintenance (1·3 mg/m2 intravenously once every 2 weeks, for 2 years) and observation. Of 135 eligible patients, 115 (85%) proceeded to ASCT, 60 (44%) were randomised. With a median follow‐up of 77·5 months for patients still alive, 5‐year event‐free survival (EFS) was 51% (95% CI 42–59%); 5‐year overall survival (OS) was 73% (95% CI 65–80%). The median follow‐up of randomised patients still alive was 71·5 months. Patients with bortezomib maintenance had a 5‐year EFS of 63% (95% CI 44–78%) and 5‐year OS of 90% (95% CI 72–97%). The patients randomised to observation had 5‐year PFS of 60% (95% CI, 40–75%) and OS of 90% (95% CI 72–97%). In conclusion, in this phase II study we found no indication of a positive effect of bortezomib maintenance after ASCT.

Keywords: bortezomib, cytarabine, maintenance therapy, Mantle cell lymphoma, phase II trial, randomised

Introduction

The prognosis of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has improved considerably with the introduction of rituximab, high‐dose cytarabine and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in first‐line treatment (Dreyling et al., 2017). The conditioning regimen may consist of BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan) or total‐body irradiation in combination with chemotherapy (Hoster et al., 2016).

The Dutch Haematology‐Oncology Cooperative Group (HOVON) has previously investigated the role of three cycles of R‐CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) followed in responding patients by one cycle of high‐dose cytarabine (HD‐Ara‐C) and ASCT in MCL (van't Veer et al., 2009). In this phase II study (HOVON 45), the 4‐year progression‐free survival (PFS) was 44%, and the 4‐year overall survival (OS) was 66%. In order to increase the PFS and OS we designed a subsequent study (HOVON 75) in which we changed three aspects: first, HD‐Ara‐C was given to all patients, irrespective of the response to R‐CHOP. Second, we added a second cycle of HD‐Ara‐C to induction therapy based on positive results from studies of the Nordic group (Geisler et al., 2008). Finally, to explore if bortezomib maintenance therapy after ASCT could be of benefit, we randomised transplanted patients to bortezomib maintenance or no further treatment. Bortezomib was chosen for this purpose based on its efficacy in relapsed/refractory MCL. A response rate of about 45% with a median duration of about 12 months was achieved in several clinical studies. Based on these favourable results, bortezomib received approval for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL (Fisher et al., 2006; Goy et al., 2009; Kane et al., 2007; Zinzani et al., 2013).

Patients and methods

Eligibility

Patients 18–65 years with newly‐diagnosed MCL, Ann Arbor stage II to IV, with WHO performance status 0 to 2 and measurable disease were eligible for study participation. Primary diagnosis was made on a representative lymph node or extranodal site biopsy sample and included histological and complete immunohistochemical assessment according to the criteria of the WHO classification (WHO 2008, as valid during inclusion and largely unchanged in the present WHO classification 2016). Confirmation of the diagnosis by central pathology review was part of the quality assessment and performed by two hematopathologists (DDJ, REK) according to routine procedures by the HOVON Pathology Facility (www.hovon.nl). Exclusion criteria were creatinine clearance <50 ml/min, CNS involvement, HIV or hepatitis B or C positivity, peripheral neuropathy >grade 2, other active malignancy and other serious medical conditions that could interfere with study treatment.

Patients who completed BEAM consolidation with ASCT, with recovery of neutrophils to >0·5 × 109/l and platelets to >80 × 109/l, without neuropathy grade 2 or more, were eligible for randomisation between bortezomib maintenance and no further treatment.

Staging procedures and response monitoring

Staging workup consisted of standard cervical, thoracic and abdominal CT scans. Bone marrow involvement was assessed by cytomorphologic and immunologic examination of bone marrow aspirate and histology of bone marrow trephine. If clinically indicated, endoscopy or other investigations for extranodal localisations were performed. Response was evaluated according to the 1999 Cheson criteria (Cheson et al., 1999). Response evaluation was performed after the 2nd HD‐Ara‐C cycle and after ASCT before randomisation. During the maintenance phase, patients were evaluated with CT‐scan and bone marrow analysis at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. During further follow‐up, patients were evaluated every 6 months, and at the moment of relapse or progression.

Study design

This investigator‐initiated, multicentre, phase II trial was designed, performed and sponsored by HOVON, and was conducted in 15 centres in the Netherlands. All patients were registered and randomised via the internet through TOP (Trial Online Process; https://www.hdc.hovon.nl/top/logon.asp). No stratification factors according to baseline characteristics were defined.

The treatment schedule consisted of three cycles of R‐CHOP21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2 day 1, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 day 1, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 day 1, vincristine 1·4 mg/m2 day 1 (max 2 mg), all intravenous (IV), and prednisone 100 mg day 1–5 orally), followed by two cycles of cytarabine [2 × 2 g/m2 IV day 1–4 (every 12 hours) in a 3‐hours saline infusion] and rituximab (375 mg/m2, IV) on day 11 aiming at in vivo purging of CD20 + mantle cells during mobilisation. One of the cytarabine cycles was used for stem cell mobilisation with G‐CSF to be started at day 8. A minimum of 3 × 106 CD34 + cells/kg was considered sufficient for transplantation. Patients in partial (PR) or complete remission (CR) after the second cycle of HD‐Ara‐C continued with ASCT after BEAM conditioning (carmustine 300 mg/m2 day −7, cytarabine 2 × 100 mg/m2 day −6 to −3, etoposide 2 × 100 mg/m2 day −6 to −3 and melphalan 140 mg/m2 day −2, IV). All other patients went off protocol.

Patients with a PR or CR after ASCT with a neutrophil count >0·5 × 109/l and platelets >80 × 109/l were randomised (1:1) between bortezomib and no further treatment. Bortezomib 1·3 mg/m2 IV (provided by Janssen–Cilag B.V., Beerse, Belgium) was given once every 2 weeks, for 2 years, starting between 6 and 12 weeks after transplantation. If bortezomib was not started within 12 weeks after ASCT, the patient went off protocol. Bortezomib maintenance had to be stopped after progression or relapse and when bortezomib maintenance was interrupted for more than 6 weeks. Before each bortezomib dose, the patient was evaluated for possible toxicities. Bortezomib should be withheld in case of febrile neutropenia until resolution of that condition, grade 4 haematological toxicity until sufficient recovery (haemoglobin >7·0 g/dl, neutrophils >0·5 × 109/l, and platelet count >50 × 109/l) and grade ≥3 non‐hematological toxicity until the toxicity recovered to at least grade 2. After (partial) resolution, the doses had to be adjusted. If the toxicity did not resolve after dosing had been withheld for 2 weeks, the patient discontinued treatment. Neuropathic pain and/or peripheral sensory neuropathy had to be managed following specific guidelines.

All patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Erasmus MC Rotterdam and the participating sites, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial is registered at the Dutch Trial Registry (www.trialregister.nl, no. NTR1772).

Statistical analysis and definition of endpoints

This study was explorative as to the effect of bortezomib maintenance. The induction regimen was changed in two ways compared to our previous regimen. To get an indication if, in addition, bortezomib maintenance could be of any benefit, it was decided to have a control arm without maintenance. The aim was to continue to a randomised phase III study if it was feasible and showed an indication of a possible effect, within the limitations of a phase II study. The target number of patients to be randomised was 60, requiring an estimated 90 primary registered patients. However, after registration of 70 patients, only 44% were randomised. Therefore, the target number of patients to be registered was increased to 135 eligible patients.

The primary endpoint was EFS from randomisation (applied to all eligible randomised patients), defined as the time from randomisation to failure or death from any cause, whichever comes first. OS was defined as the time from registration until death from any cause. Patients still alive at the date of last contact were censored. Failure was defined as either no response on treatment or relapse; PR was not defined as failure.

For the efficacy of the maintenance treatment, EFS (primary endpoint of this study) and OS were calculated with the method of Kaplan–Meier. The median and probabilities at 2 years were calculated together with 95% confidence intervals. The safety of bortezomib maintenance was evaluated by tabulation of the (serious) adverse events, coded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, CTCAE version 3.0.

Cox regression analysis and the associated likelihood ratio test were used to test for trends with continuous or ordinal variables. P‐values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between October 2007 and March 2012, 140 patients with a median age of 57 (range 34–66) were included. The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of the patients were male (78%) and patients presented generally with stage IV disease (86%). Central pathology review was performed in 136/140 registered patients. A diagnosis of CD20 and CyclinD1 positive MCL could be confirmed in 131 cases. In three cases a diagnosis of another B‐cell lymphoma class was made (B‐CLL, NMZL, multiple myeloma), and in two cases material was considered insufficient for a classifying diagnosis. These five patients were considered ineligible in hindsight and excluded from analysis. MIB1 quantification was performed in 87/131 MCL cases confirmed at review with 25/87 (28,7%) with a MIB1 index ≥30%. In 114/131 confirmed MCL, SOX11 was performed, of which four were negative. Of these, however, two cases had either blastoid morphology or P53 protein expression both with high MIB1 indices. A low MIPI score (Hoster et al., 2008) was present in 57% of the patients.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics.

| All patients n = 135 | Randomised patients after ASCT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No further treatment n = 30 | Bortezomib maintenance n = 30 | |||

| Age (median; range) | 57 (34–66) | 54 (36–65) | 56 (34–66) | |

| Male sex | 78% | 77% | 80% | |

| WHO performance | ||||

| WHO 0 | 105 (78%) | 25 (83%) | 25 (83%) | |

| WHO 1 | 60 (19%) | 5 (17%) | 4 (13%) | |

| WHO 2 | 5 (4%) | 1 (3%) | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | ||||

| II | 11 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) | |

| III | 8 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | |

| IV | 116 (86%) | 27 (90%) | 25 (83%) | |

| MIPI score | ||||

| Low | 77 (57%) | 21 (70%) | 15 (50%) | |

| Intermediate | 43 (32%) | 6 (20%) | 11 (37%) | |

| High | 13 (10%) | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1%) | 1 (3%) | ||

| Bone marrow involvement | 112 (83%) | 26 (87%) | 24 (80%) | |

| MIB1 | <30% | 62 (46%) | 11 (37%) | 17 (57%) |

| ≥30% | 25 (18%) | 8 (26%) | 5 (17%) | |

| unknown | 48 (36%) | 11 (37%) | 8 (26%) | |

| P53 | <50% | 68 (50%) | 17 (57%) | 18 (60%) |

| ≥50% | 7 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| unknown | 60 (45%) | 12 (40%) | 12 (40%) | |

Induction treatment and ASCT

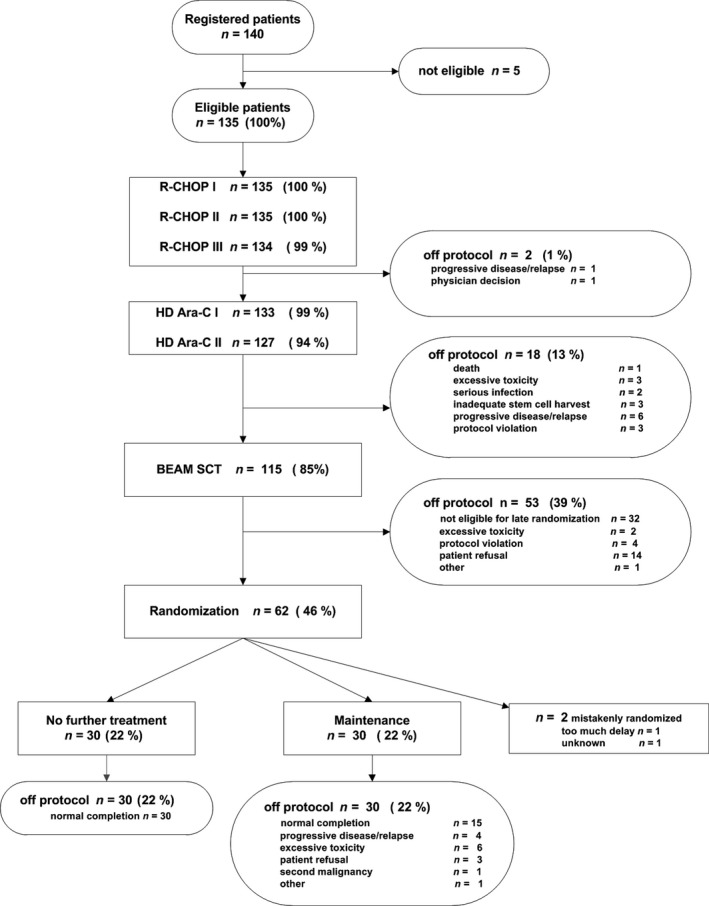

The consort diagram is presented in Fig. 1. Out of 135 eligible patients at registration, 134 received all three R‐CHOP cycles and 127 patients received both HD‐Ara‐C cycles. Response evaluation showed that 79 patients (63%) achieved a CR/CRu and 39 patients (31%) a PR. Three patients had stable disease, two patients had PD and, in four patients, response at this point was unknown. 115 patients proceeded to ASCT (Fig. 1). Reasons for not proceeding to ASCT were insufficient response (n = 6), insufficient stem cell harvest (n = 3) or other reasons (n = 3). The response after BEAM and ASCT improved: 99 patients (86%) achieved a CR/CRu and 15 patients (13%) a PR. One patient was not restaged. A median of three (0–19) platelet transfusions and a median of three (0–16) red blood cell transfusions were given. The median time to white blood cell recovery >0·5 × 109/l was 25 days (16–139); the median recovery time to platelets >50 × 109/l was 27 days (17–632).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of all patients.

Maintenance randomisation after ASCT

After ASCT, 62 of 115 transplanted patients were randomised for bortezomib (n = 31) or no further treatment (n = 31). After randomisation, one patient in each arm was found ineligible, therefore, 30 patients in each study arm were analysed for the maintenance phase. Of 53 patients who were not randomised, the majority were excluded according to protocol (insufficient bone marrow/haematological recovery, especially low platelet count) and refusal (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the randomised patients were well‐balanced between both arms, apart from the MIPI score, with fewer patients with a low MIPI score in the bortezomib arm (50% vs. 70%) (Table 1).

Outcome

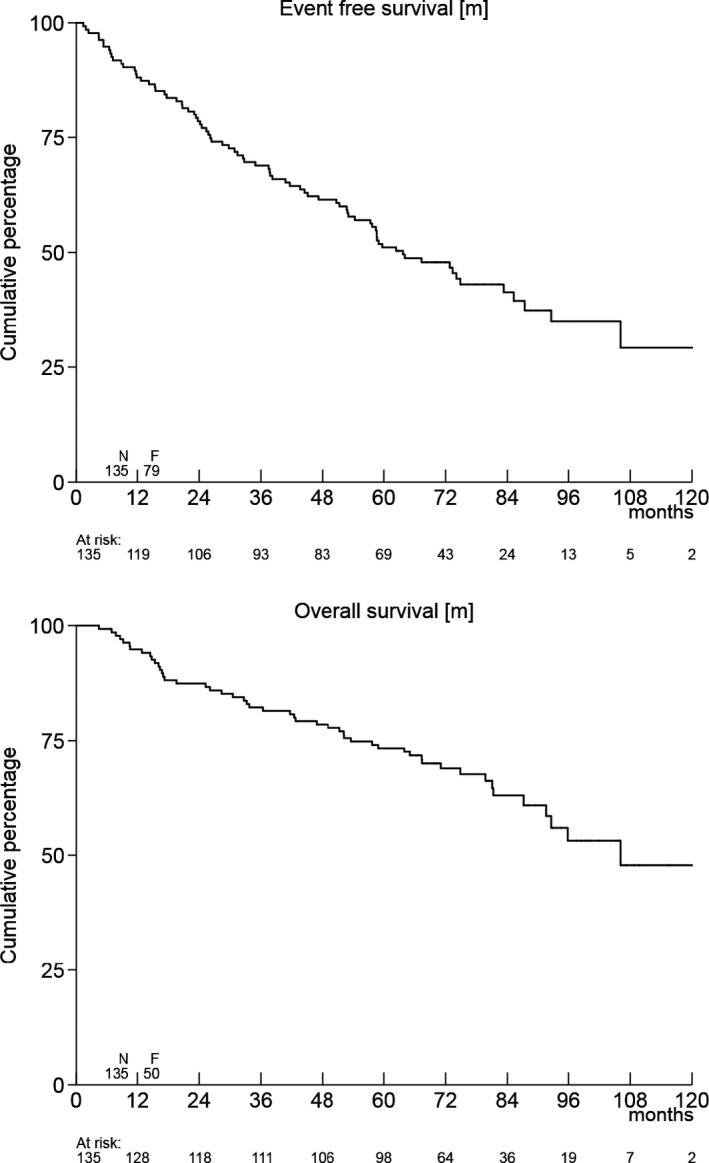

With a median follow‐up of 77·5 months for all patients alive, the EFS at 5 years was 51%, and the OS 73% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Event‐free survival and overall survival of all 135 patients.

Thirty‐seven percent of patients (n = 50) died. Causes of death were MCL (n = 26, 52%), treatment‐related (n = 1, 2%), intercurrent disease (n = 5, 10%), secondary malignancy (n = 4, 8%), unknown (n = 4, 8%) and other (n = 10, 20%). Seven of these last 10 patients died of complications from allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

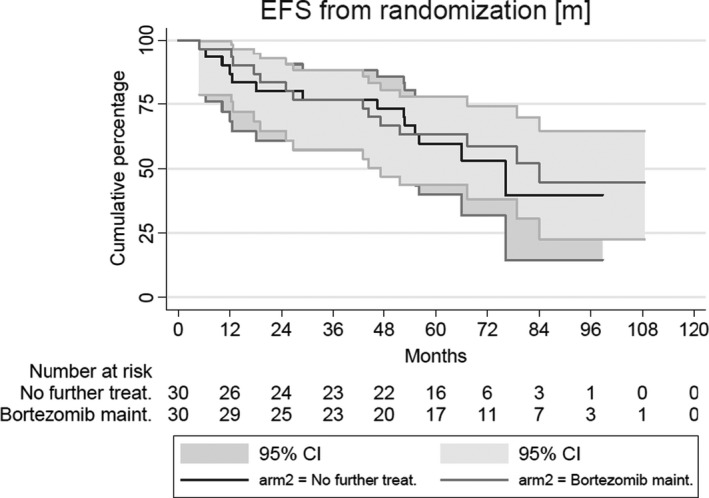

The median follow‐up of the randomised patients still alive was 71·5 months. The EFS at 2 years was 83% in the bortezomib arm (95% CI 65–93%), and in the patients without maintenance 80% (95% CI 61–90%). The EFS at 5 years was also similar in both arms, with 63% (95% CI 44–78%; P = 0·73) in the patients treated with bortezomib versus 60% (95% CI 40–75%) for the patients without maintenance treatment (Fig. 3). The 5‐year OS was identical with 90% (95% CI 72–97%) in both arms.

Figure 3.

Event‐free survival of randomised patients.

Toxicity of bortezomib maintenance

A planned interim analysis was performed in October 2011, based upon data from 2 × 15 randomised patients with a follow‐up of at least 3 months after randomisation. No unexpected toxicity was observed and it was decided to continue enrolment as planned.

The median duration of maintenance therapy was 21 months. Out of 30 patients randomised to bortezomib maintenance therapy, 15 continued the bortezomib therapy for the planned 24 months, while 15 patients received bortezomib treatment for a median of 14 months (range 0–23). The reasons to stop early were progressive disease (n = 4), excessive toxicity (n = 6), refusal to start (n = 2) or continue after the first dose (n = 1), second malignancy (n = 1) and unknown (n = 1). Neurological adverse events grade 2 were observed in four patients and grade 3 in one patient; no grade 4 neurological adverse events were observed.

Secondary malignancy

Fifteen patients (11%) developed a secondary malignancy; six of these had received bortezomib maintenance. They developed non‐melanoma skin cancer (n = 2), melanoma (n = 1), prostate cancer (n = 1), oropharynx carcinoma (n = 1) and neuro‐endocrine carcinoma (n = 1).

In the observation arm, nine patients developed a secondary malignancy [non‐melanoma skin cancer (n = 4), adenocarcinoma (n = 3) and lung cancer (n = 2)].

Discussion

This phase II randomised trial (HOVON 75) was designed upon the basis of the earlier HOVON 45 study (van’t Veer et al., 2009). We aimed at improvement in outcome by continuing treatment of all patients after R‐CHOP with high‐dose ARA‐C, irrespective of response, and by giving two cycles of ARA‐C instead of one. Responding patients would continue to ASCT. The outcome of the present study compares favourably to the previous study. Therefore, these interventions seem worthwhile. In the HOVON 45 study, 70% of the patients could be transplanted compared to 85% in the current study. In the previous control study, a 4‐year failure‐free survival of 36% and OS of 66% were achieved; in the current HOVON 75 study, the EFS at 5 years was 51%, and the OS 73%. This suggests an important role of cytarabine in the induction treatment of MCL, as reported in other studies (Geisler et al., 2008;Hermine et al., 2016).

A second aim of our study was to investigate if bortezomib maintenance after ASCT would be feasible and could improve outcome. This approach was new at the time. To this end, we decided to have a parallel control arm without maintenance. Bortezomib maintenance was feasible, although the number of patients that could be randomised was lower than expected due to insufficient recovery of the blood counts after ASCT. Our study did not show any difference in EFS.

This trial had a few limitations. Compared to the regimen we used before (HOVON 45) we changed the protocol on three points, so it is not clear which of the interventions resulted in the observed better outcome. The study encountered unexpected difficulties in that many patients did not reach the pre‐specified platelet count of >80 × 109/l before week 12 after ASCT, resulting in a lower than expected number of patients to be randomised. The protocol therefore was amended to increase sample size of patients registered in the study. Finally, the small number of patients randomised (phase II design) resulted in a relatively low statistical power and the chance of missing a positive effect. However, the completely overlapping curves suggest that bortezomib monotherapy does not have a benefit in the context of maintenance. Therefore, there is no indication to initiate a phase III study.

Bortezomib maintenance in MCL patients has also been studied by the CALGB. In this randomised phase II study (50403), bortezomib maintenance (bortezomib 1·6 mg/m2 weekly 4 of 8 weeks for 18 months), was compared with a consolidation scheme (bortezomib 1·3 mg/m2 days 1, 4, 8 and 11 of a 3 week cycle for four cycles) after ASCT. Both bortezomib arms performed equally at 5 years, showing PFS of 70% vs. 69%, respectively. The authors compared these results with those from their previous study without maintenance or consolidation (59909), which demonstrated a 5‐year PFS of 51%. They suggest a benefit from bortezomib consolidation or maintenance (Kaplan et al., 2015). However, caution should be applied in comparing these studies, as the 50403 study did not have a direct control arm without bortezomib. We conclude, therefore, that there are still no strong data to support the use of bortezomib maintenance after ASCT in MCL.

At the time our study was designed, there was no scientific evidence to support the added value of maintenance therapy after ASCT. In contrast, rituximab maintenance until progression resulted in an impressive improvement (hazard ratio 0·55) of PFS and even OS in elderly MCL patients after induction therapy with R‐CHOP (Kluin‐Nelemans et al., 2012). Since then, rituximab maintenance is considered standard therapy for elderly patients (Dreyling et al., 2014). Meanwhile, two different approaches were developed for treatment of young MCL patients after ASCT. First, the Nordic group prospectively assessed minimal residual disease (MRD) in patients treated in the MCL2 trial (Andersen et al., 2009). For those patients who developed a molecular relapse after ASCT, pre‐emptive treatment with rituximab was initiated (four weekly administrations of 375 mg/m2). The large majority (92%) converted to molecular remission again, but remission‐free survival curves did not show a plateau, indicating that additional rounds of rituximab or other therapies are needed. The authors stressed that any maintenance therapy should have a duration of more than 2 years, as the mean interval of molecular relapse after transplantation in their study was 18·5 months, with patients relapsing even after 6 years (Andersen et al., 2009). In a long‐term follow‐up it was shown that patients who have a late (>1 year post‐ASCT) molecular relapse did well, whereas patients with short (<1 year from transplant) molecular response duration also had a short clinical response duration (Geisler et al., 2012).

The second successful approach to improve the remission duration after ASCT was described by the French LyMA group (Le Gouill et al., 2017). In this randomised phase III trial, patients received rituximab every 2 months for 3 years or no further treatment. Rituximab significantly improved both the PFS (83% at 4 years vs. 64%) and the OS (89% vs. 80%). In an ongoing study (MCL0208), the Italian FIL group is investigating the role of maintenance with lenalidomide for the same group of younger post‐ASCT patients.

Lenalidomide has been linked with the occurrence of second primary malignancies (Dimopoulos et al., 2012). In our study, in which no lenalidomide was given, we observed 15 cases, of whom six had received bortezomib.

Since the design of our study, other groups have published results of other induction regimens. The European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network performed a large randomised trial comparing a regimen with high‐dose ARA‐C, that is, alternating R‐CHOP with R‐DHAP with R‐CHOP only (Hermine et al., 2016). The response rate was 94% vs. 90% respectively, and the CR/CRu rate was 55% vs. 39%. The LyMA group used four cycles of R‐DHAP before ASCT, which resulted in a response rate of 94% and 77% CR/CRu. (Le Gouill et al., 2017). Finally, the Nordic MCL2 trial should be mentioned, which used for induction rituximab with augmented CHOP (maxi‐CHOP) followed by ASCT after conditioning with BEAM or BEAC. An updated follow‐up of more than 6·5 years showed a median OS and remission duration of longer than 10 years and a median event‐free survival of 7·4 years (Geisler et al., 2012).

Currently, a large randomised study of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network is examining the role of ibrutinib in upfront therapy of transplant eligible patients. The basis of induction treatment is the alternating R‐CHOP/R‐DHAP regimen. This is the only induction regimen that has proved to be superior in a randomised study.

In conclusion, although the outcome of young patients with MCL is still improving, the absence of a plateau in the EFS after induction therapy, including ASCT, demands both improvements in the induction therapy and interventions thereafter. Our study confirmed the important role of ARA‐C in the induction of young MCL patients. There was no indication that bortezomib maintenance after ASCT may improve outcome of MCL patients after ASCT. Other options, especially BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib, may be explored to reduce relapse after ASCT.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the local and central data managers for collecting and verifying patient data. They also thank the HOVON Data Center for continuous support in the trial process.

References

- Andersen, N.S. , Pedersen, L.B. , Laurell, A. , Elonen, E. , Kolstad, A. , Boesen, A.M. , Pedersen, L.M. , Lauritzsen, G.F. , Ekanger, R. , Nilsson‐Ehle, H. , Nordstrom, M. , Freden, S. , Jerkeman, M. , Eriksson, M. , Vaart, J. , Malmer, B. & Geisler, C.H. (2009) Pre‐emptive treatment with rituximab of molecular relapse after autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 4365–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson, B.D. , Horning, S.J. , Coiffier, B. , Shipp, M.A. , Fisher, R.I. , Connors, J.M. , Lister, T.A. , Vose, J. , Grillo‐López, A. , Hagenbeek, A. , Cabanillas, F. , Klippensten, D. , Hiddemann, W. , Castellino, R. , Harris, N.L. , Armitage, J.O. , Carter, W. , Hoppe, R. & Canellos, G.P. (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17, 1244–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos, M.A. , Richardson, P.G. , Brandenburg, N. , Yu, Z. , Weber, D.M. , Niesvizky, R. & Morgan, G.J. (2012) A review of second primary malignancy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide. Blood, 119, 2764–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling, M. , Campo, E. , Hermine, O. , Jerkeman, M. , Le, G.S. , Rule, S. , Shpilberg, O. , Walewski, J. & Ladetto, M. (2017) Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Annals of Oncology, 28, iv62‐iv71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling, M. , Geisler, C. , Hermine, O. , Kluin‐Nelemans, H.C. , Le, G.S. , Rule, S. , Shpilberg, O. , Walewski, J. & Ladetto, M. (2014) Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Annals of Oncology, 25, iii83–iii92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.I. , Bernstein, S.H. , Kahl, B.S. , Djulbegovic, B. , Robertson, M.J. , De Vos, S. , Epner, E. , Krishnan, A. , Leonard, J.P. , Lonial, S. , Stadtmauer, E.A. , O'Connor, O.A. , Shi, H. , Boral, A.L. & Goy, A. (2006) Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24, 4867–4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, C.H. , Kolstad, A. , Laurell, A. , Andersen, N.S. , Pedersen, L.B. , Jerkeman, M. , Eriksson, M. , Nordstrom, M. , Kimby, E. , Boesen, A.M. , Kuittinen, O. , Lauritzsen, G.F. , Nilsson‐Ehle, H. , Ralfkiaer, E. , Akerman, M. , Ehinger, M. , Sundstrom, C. , Langholm, R. , Delabie, J. , Karjalainen‐Lindsberg, M.L. , Brown, P. & Elonen, E. (2008) Long‐term progression‐free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front‐line immunochemotherapy with in vivo‐purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood, 112, 2687–2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, C.H. , Kolstad, A. , Laurell, A. , Jerkeman, M. , Raty, R. , Andersen, N.S. , Pedersen, L.B. , Eriksson, M. , Nordstrom, M. , Kimby, E. , Bentzen, H. , Kuittinen, O. , Lauritzsen, G.F. , Nilsson‐Ehle, H. , Ralfkiaer, E. , Ehinger, M. , Sundstrom, C. , Delabie, J. , Karjalainen‐Lindsberg, M.L. , Brown, P. & Elonen, E. (2012) Nordic MCL2 trial update: six‐year follow‐up after intensive immunochemotherapy for untreated mantle cell lymphoma followed by BEAM or BEAC + autologous stem‐cell support: still very long survival but late relapses do occur. British Journal of Haematology, 158, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goy, A. , Bernstein, S.H. , Kahl, B.S. , Djulbegovic, B. , Robertson, M.J. , De Vos, S. , Epner, E. , Krishnan, A. , Leonard, J.P. , Lonial, S. , Nasta, S. , O'Connor, O.A. , Shi, H. , Boral, A.L. & Fisher, R.I. (2009) Bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: updated time‐to‐event analyses of the multicenter phase 2 PINNACLE study. Annals of Oncology, 20, 520–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermine, O. , Hoster, E. , Walewski, J. , Bosly, A. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Thieblemont, C. , Szymczyk, M. , Bouabdallah, R. , Kneba, M. , Hallek, M. , Salles, G. , Feugier, P. , Ribrag, V. , Birkmann, J. , Forstpointner, R. , Haioun, C. , Hanel, M. , Casasnovas, R.O. , Finke, J. , Peter, N. , Bouabdallah, K. , Sebban, C. , Fischer, T. , Duhrsen, U. , Metzner, B. , Maschmeyer, G. , Kanz, L. , Schmidt, C. , Delarue, R. , Brousse, N. , Klapper, W. , Macintyre, E. , Delfau‐Larue, M.H. , Pott, C. , Hiddemann, W. , Unterhalt, M. & Dreyling, M. (2016) Addition of high‐dose cytarabine to immunochemotherapy before autologous stem‐cell transplantation in patients aged 65 years or younger with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL Younger): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet, 388, 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoster, E. , Dreyling, M. , Klapper, W. , Gisselbrecht, C. , Van, H.A. , Kluin‐Nelemans, H.C. , Pfreundschuh, M. , Reiser, M. , Metzner, B. , Einsele, H. , Peter, N. , Jung, W. , Wormann, B. , Ludwig, W.D. , Duhrsen, U. , Eimermacher, H. , Wandt, H. , Hasford, J. , Hiddemann, W. & Unterhalt, M. (2008) A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood, 111, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoster, E. , Geisler, C.H. , Doorduijn, J. , Van der Holt, B. , Walewski, J. , Bloehdorn, J. , Ribrag, V. , Salles, G. , Hallek, M. , Pott, C. , Szymczyk, M. , Kolstad, A. , Laurell, A. , Raty, R. , Jerkeman, M. , Van't Veer, M. , Kluin‐Nelemans, J.C. , Klapper, W. , Unterhalt, M. , Dreyling, M. & Hermine, O. (2016) Total body irradiation after high‐dose cytarabine in mantle cell lymphoma: a comparison of Nordic MCL2, HOVON‐45, and European MCL Younger trials. Leukemia, 30, 1428–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane, R.C. , Dagher, R. , Farrell, A. , Ko, C.W. , Sridhara, R. , Justice, R. & Pazdur, R. (2007) Bortezomib for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 13, 5291–5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, L.D. , Jung, S.H. , Stock, W. , Bartlett, N.L. , Pitcher, B. , Byrd, J.C. , Blum, K.A. , Lacasce, A.S. , Fulton, N. , Hsi, E.D. , Hurd, D.D. , Czuczman, M. , Leonard, J.P. & Cheson, B.D. (2015) Bortezomib maintenance (BM) versus consolidation (BC) following aggresssive immunochemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for untreated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): CALBG (alliance) 50403 (Abstract). Blood, 126, 337. [Google Scholar]

- Kluin‐Nelemans, H.C. , Hoster, E. , Hermine, O. , Walewski, J. , Trneny, M. , Geisler, C.H. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Thieblemont, C. , Vehling‐Kaiser, U. , Doorduijn, J.K. , Coiffier, B. , Forstpointner, R. , Tilly, H. , Kanz, L. , Feugier, P. , Szymczyk, M. , Hallek, M. , Kremers, S. , Lepeu, G. , Sanhes, L. , Zijlstra, J.M. , Bouabdallah, R. , Lugtenburg, P.J. , Macro, M. , Pfreundschuh, M. , Prochazka, V. , Di, R.F. , Ribrag, V. , Uppenkamp, M. , Andre, M. , Klapper, W. , Hiddemann, W. , Unterhalt, M. & Dreyling, M.H. (2012) Treatment of older patients with mantle‐cell lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 367, 520–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gouill, S. , Thieblemont, C. , Oberic, L. , Moreau, A. , Bouabdallah, K. , Dartigeas, C. , Damaj, G. , Gastinne, T. , Ribrag, V. , Feugier, P. , Casasnovas, O. , Zerazhi, H. , Haioun, C. , Maisonneuve, H. , Houot, R. , Jardin, F. , Van Den Neste, E. , Tournilhac, O. , Le, D.K. , Morschhauser, F. , Cartron, G. , Fornecker, L.M. , Canioni, D. , Callanan, M. , Bene, M.C. , Salles, G. , Tilly, H. , Lamy, T. , Gressin, R. & Hermine, O. (2017) Rituximab after autologous stem‐cell transplantation in mantle‐cell lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 1250–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van’t Veer, M.B. , de Jong, D. , MacKenzie, M. , Kluin‐Nelemans, H.C. , van Oers, M.H.J. , Zijlstra, J. , Hagenbeek, A. & van Putten, W.L.J. (2009) High‐dose Ara‐C and beam with autograft rescue in R‐CHOP responsive mantle cell lymphoma patients. British Journal of Haematology, 144, 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzani, P.L. , Pellegrini, C. , Merla, E. , Ballerini, F. , Fabbri, A. , Guarini, A. , Pavone, V. , Quintini, G. , Puccini, B. , Vigliotti, M.L. , Stefoni, V. , Derenzini, E. , Broccoli, A. , Gandolfi, L. , Quirini, F. , Casadei, B. , Argnani, L. & Baccarani, M. (2013) Bortezomib as salvage treatment for heavily pretreated relapsed lymphoma patients: a multicenter retrospective study. Hematological Oncology, 31, 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]