Abstract

The case report literature on ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz (UVAL) is scant, and specific guidelines on its diagnosis and treatment are lacking. Our study's aim was to perform a systematic literature review of UVAL in order to formulate a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Using the PRISMA criteria, we searched PubMed and MEDLINE for the terms ‘ulcus vulvae acutum’, ‘Lipschütz ulcer’ and ‘acute genital ulcer AND vulva’. We extracted relevant data on ‘type of article’, ‘patients’ age’, ‘amount and localization of ulcers’, ‘presence of flu‐like symptoms’, ‘prior sexual contacts’, ‘diagnostic workup’ (including histology, blood count and serology such as Epstein–Barr virus testing) and ‘treatment/outcome’. Data were meta‐analysed and comparative analyses were discussed in order to create a diagnostic algorithm and recommendations for management. Twenty‐one publications reporting a total of 60 cases of UVAL were included for analysis. On this basis, we formulated a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm defined by two major and four minor criteria. The major criteria were (i) acute onset of one or more painful ulcerous lesions in the vulvar region and (ii) exclusion of infectious and non‐infectious causes for the ulcer. The minor criteria were (i) localization of ulcer at vestibule or labia minora, (ii) no sexual intercourse ever (i.e. patient was a virgin) or within the last 3 months, (iii) flu‐like symptoms and/or (iv) systemic infection within 2–4 weeks prior to onset of vulvar ulcer. Use of a symptom‐based treatment algorithm based on our proposed major and minor criteria will improve the diagnosis and management of UVAL.

Introduction

In the early 20th century, Lipschütz described a case series of virgins who developed painful vulvar ulcers of unknown aetiology for which he coined the term ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz (UVAL).1 These ulcers usually occur quickly and are diagnosed by exclusion of other diseases.2, 3, 4 Although the aetiology still needs to be fully elucidated,2, 5 UVAL has been linked to various bacterial or viral infections, such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV).3, 5, 6, 7, 8 These ulcers have a predilection for the labia minora, but also occur at other sites, such as the labia majora or the perineal region.2, 5 They usually present as a single deep ulcerated lesion of remarkable size that is sharply demarcated, painful and marked by fibrinous coatings or greyish exudate.2, 5, 9 Affected patients are typically young and in many cases, virgins3 and often present with flu‐like symptoms such as fever, fatigue or lymphadenitis.2, 4, 8 Lesions can spontaneously resolve within weeks, and antibiotics or corticosteroids are often prescribed.

Since few case reports and case series of UVAL have been reported in the literature, the disease might be underdiagnosed, and there are no specific guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. The aim of this study was to review systematically the literature on UVAL in order to formulate a diagnostic algorithm and recommendations for management.

Methods

Our systematic literature review was performed according to the PRISMA criteria for reviews and meta‐analyses.10 We searched PubMed and MEDLINE for relevant keywords ‘ulcus vulvae acutum’, ‘Lipschütz ulcer’ and ‘acute genital ulcer AND vulva’. We included a publication in our analysis data set if it (i) presented a case report, case series or review article on UVAL; (ii) was published in 1990 or later; and (iii) was written in English, listed in MEDLINE, and published in a peer‐reviewed journal. We excluded a publication if it (i) was published in a language other than English, (ii) focused on genital ulceration but not on UVAL or (iii) focused predominantly on histopathology. From all included publications, we extracted data reporting the number of cases, ‘type of article’, ‘patients’ age’, ‘amount and localization of ulcers’, ‘presence of flu‐like symptoms’, ‘prior sexual contacts’, ‘relevant diagnostic workup (including histology, blood count and serology such as EBV testing) and ‘treatment’. In addition, we manually searched all relevant manuscripts listed in the bibliographies of the publications included in our data set using the same search terms described above. In case of disagreement of data extraction, consensus was reached with help of the senior author.

Results

Analysis data set

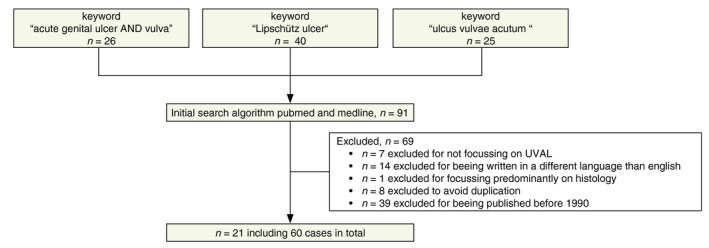

Our literature search identified 91 reports. Sixty of those reports were excluded: seven because they did not focus on UVAL, 14 because they were written in a language other than English and 39 because they were published after 1990. Another eight publications were excluded because they were duplicates. We finally included 21 publications in our analysis data set (Table 1) encompassing one case series that included 33 patients3 and 20 case reports that included 27 patients for an overall total of 60 patient cases.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Table 1.

Characteristics of included published reports

| First author, year of publication | Type of article | Included cases | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delgado‐Garcia 20145 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 2 | Hernandez Nunez 200811 | CR | 4 | IV |

| 3 | Pelletier 200313 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 4 | Fremlin 201714 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 5 | Wolters 201715 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 6 | Mourinha 201616 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 7 | Garcia201617 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 8 | Vieira‐Baptista 20163 | CS | 33 | IV |

| 9 | Haidari 201518 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 10 | Kinyo 201419 | CR | 2 | IV |

| 11 | Burguete Archel 20136 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 12 | Brinca201220 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 13 | Truchuelo 20128 | CR | 2 | IV |

| 14 | Chanal 20104 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 15 | Ales‐Fernandez 201021 | CR | 3 | IV |

| 16 | Martin 200822 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 17 | Sardy 20117 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 18 | Wetter 200823 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 19 | Trcko 200724 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 20 | Svedmann 20049 | CR | 1 | IV |

| 21 | Török 200012 | CR | 1 | IV |

| Publication years 2000–2017 |

CR: n = 20 CS: n = 1 |

CR: n = 27 CS: n = 33 |

Level IV: n = 21 |

|

CR, case report; CS, case series.

A flow diagram of our systematic literature search results is shown in Figure 1. One review was further used for discussion.2

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study identification.

Meta‐analysis of the literature

Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 summarize the findings of our systematic review by ‘type of article’, ‘patients’ age’, ‘amount and localization of ulcers’, ‘presence of flu‐like symptoms’, ‘prior sexual contacts’, ‘relevant diagnostic workup’ (including histology, blood count, serology such as EBV testing) and ‘treatment/outcome’. Table 1 identifies each publication by first author and year (ranging from 2000 to 2017), type of article (the case series of 33 patients and the 20 individual case reports referred to above) and level of evidence (all level IV). Tables 2 and 3 describe the demographic, clinical and diagnostic workup data for all 60 patient cases identified in the literature. Table 4 summarizes treatments and outcomes. Since we had no access to the raw data for the case series of 33 patients3 and thus could not fully evaluate the individual patient cases in the case series, we present below the results from our analysis of the 20 individual case reports for 27 patients first and the results from our analysis of the case series of 33 patients second.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data of the included patients suffering from UVAL

| Age of patient | Oral apthosis | Flu‐ like symptoms | Amount of ulcers | Localization of ulcers | Prior sexual contact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 years | − | + | 1 | LMA | − |

| 2 | 14 years | NA | + | 4 | LMI | − |

| 14 years | NA | + | 1 | LMI | − | |

| 12 years | NA | + | 3 | NA | − | |

| 14 years | NA | + | 1 | LMA | − | |

| 3 | 25 years | − | + | 1 | LMI | − |

| 4 | 14 years | NA | + | 1 | LMI | − |

| 5 | 18 years | NA | + | 3 | LMI (2) urtehral orifice (1) | − |

| 6 | 22 years | − | + | Multiple | LMI, introitus | − |

| 7 | 12 years | − | − | 2 | LMA | − |

| 8 | 10–79 years | NA† | +! | 11 patients: single ulcer | Vestibule (19), LMI (10), clitoris (1), interlabial sulcus (1), LMA (2) | NA§ |

| 9 | 15 years | − | + | 3 | LMI | − |

| 10 | 10 years | NA | + | 2 | LMI | − |

| 25 years | + | + | 3 | LMI (2) et LMA (1) | NA | |

| 11 | 17 months | + | + | 2 | Vaginal introit and perineum | − |

| 12 | 30 years | − | + | 2 | LMI | + |

| 13 | 11 years | − | − | 1 | LMI | − |

| 11 years | − | + | 2 | LMI | − | |

| 14 | 21 years | − | − | 3 | LMA and LMI | + |

| 15 | 16 years | NA | + | 1 | LMI | − |

| 15 years | NA | + | 1 | LMI | − | |

| 2 months | NA | − | 1 | LMI | − | |

| 16 | 16 years | NA | + | Multiple | LMI | + |

| 17 | 16 years | − | + | Multiple | LMA and LMI | − |

| 18 | 13 years | + | + | 3 | LMI | − |

| 19 | 29 years | NA | − | 2 | LMI | + |

| 20 | 14 years | + | + | 1 | LMA | − |

| 21 | 17 years | − | + | 4 | LMI et LMA | − |

|

CR: 2 months to 30 years (mean: 15.5) CS: 10–79 years (mean: NA) |

CR: yes: n = 4 no: n = 11 NA: n = 12 CS: yes: 4 (NA) no: NA NA: NA |

CR: yes: n = 22 no: n = 5 CS: yes: n = 17 no: n=NA |

CR/(CS): 1: n = 10/(11) 2: n = 6/(NA) 3: n = 6/(NA) 4 or more: n = 5/(NA) |

CR/(CS): LMI: n = 21/(10) LMA: n = 8/(2) Introitus: n = 2/(NA) Urethral orifice: n = 1/(NA) Perineum: n = 1/(NA) Vestibule: n = NA/(19) Clitoris: n = NA/(1) Interlabial sulcus: n = NA/(1) |

CR/(CS): yes: n = 4/(NA) no: n = 22/(NA) NA: n = 1/(NA) |

†Not defined whether oral aphthosis – but likely in four patients. !Flu‐like symptoms where described as fever in 11 patients; myalgia in six patients. §Sexual debut 84.4%, but not defined whether ulcers occurred ‘simultaneously’.

CR, case report; CS, case series; LMA, labia majora; LMI, labia minora.

Table 3.

Individual diagnostic workup of the different manuscripts in order to identify UVAL

| Histologic analysis (result, if applicable) | Blood count | Serology | Serological results if positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV | EBV | Syphilis | HIV | Others | ||||

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | ND | − | |

| 2 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | EBV IgG and IgM positive |

| + (unspecific) | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| − | + | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | − | NA | + | + | − | − | − |

EBV: IgG positive HSV: IgG positive |

| 4 | + (unspecific) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5 | − | + | − | + | − | ND | − | EBV: IgM positive |

| 6 | − | NA | − | − | − | ND | − | |

| 7 | − | NA | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 8 | − | NAa | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | EBV: n = 2 positive (not defined whether IgM or IgG) |

| 9 | − | NA | − | + | − | ND | − | EBV: IgG positive |

| 10 | − | + | − | − | − | ND | − | |

| − | + | + | + | − | ND | + |

EBV: IgG positive HSV: IgG positive Infection of influenza B & adenovirus |

|

| 11 | + (unspecific) | + | − | + | − | − | − | EBV: IgM positive |

| 12 | + (unspecific) | + | − | + | − | − | − | EBV: IgG positive |

| 13 | − | NA | ND | − | − | − | − | |

| − | NA | ND | − | − | − | − | ||

| 14 | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | Mumps: IgM & IgG positive |

| 15 | − | + | ND | − | − | − | − | |

| − | + | ND | − | − | − | − | ||

| − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 16 | − | + | − | + | − | − | + |

EBV: IgG positive CMV: IgM& IgG positive |

| 17 | + (unspecific) | + | − | + | − | − | − | EBV: IgG & IgM positive |

| 17 | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 19 | − | + | ND | − | − | − | − | |

| 20 | − | NA | ND | + | ND | ND | + | EBV: IgM positive |

| 21 | − | + | − | − | − | ND | − | |

|

CR/(CS): yes: n = 5/(0) no: n = 23/(33) |

CR/(CS): yes: n = 17/(NA) NA: n = 10/(NA) |

+: n = 2 −: n = 16 ND: n = 6 NA: n = 4 |

+: n = 10 (plus n = 2 of CS) −: n = 14 ND: n = 0 NA: n = 3 |

+: n = 0 −: n = 23 ND: n = 1 NA: n = 4 |

+: n = 0 −: n = 16 ND: n = 8 NA: n = 4 |

+: n = 4 −: n = 20 ND: n = 0 NA: n = 4 |

||

Blood count in case of severe systemic symptoms or delayed healing.

NA, not available; ND, Not done.

Table 4.

Treatment protocols and outcomes for patients with UVAL

| Treatment | Resolved without sequelae after treatment | Recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SA, OT | + | − |

| 2 | SS, SA | + | − |

| SA | + | − | |

| OT | + | NA | |

| SS, TA | + | NA | |

| 3 | SA | + | NA |

| 4 | SS | + | NA |

| 5 | SA | + | − |

| 6 | SA, TS | + | − |

| 7 | OT | + | − |

| 8 | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 | OT | NA | NA |

| 10 | SS, OT | + | NA |

| SA, SS | NA | − | |

| 11 | SA | + | − |

| 12 | SA | + | − |

| 13 | SH | + | − |

| SH | + | − | |

| 14 | OT | + | − |

| 15 | TA | + | − |

| TA | + | − | |

| NA | + | − | |

| 16 | TA, OT | + | − |

| 17 | SS, SA, OT | + | − |

| 18 | TS | + | + |

| 19 | SA, TA, SS | − | NA |

| 20 | SS | + | − |

| 21 | SA, OT | − | − |

|

CR/(CS): SA: n = 12 (NA) TA: n = 5 (NA) SS: n = 8 (NA) TS: n = 2 (NA) SH: n = 2 (NA) OT: n = 9 (NA) |

CR/(CS): yes: n = 23 (NA) no: n = 2 (NA) NA: n = 2 (NA) |

CR/(CS): Yes: n = 1 (NA) No: n = 19 (NA) NA n = 7 (NA) |

−, no; +, yes; NA, not available; OT, others; SA, systemic antibiotics; SH, spontaneous healing; SS, systemic steroids; TA, topical antibiotics; TS, topical steroids.

Individual case reports

The 27 patients included in the 20 individual case reports ranged in age from 2 months to 30 years (mean 15.5 years). Oral aphthosis was reported in four patients (14.8%).6, 9, 19, 23 Flu‐like symptoms were reported in 22 patients (81.5%).5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 A single ulcer was reported in 10 patients (37%)5, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 21; two ulcers in six patients (22.2%)6, 8, 17, 19, 20, 24; three ulcers in six patients (22.2%)4, 11, 15, 18, 19, 23; and ≥4 ulcers in five patients (18.5%).7, 11, 12, 16, 22 The labia minora and labia majora were affected in 21 patients (77.7%)4, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and eight patients (29.6%),4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 17, 19 respectively. Localization was reported to the introitus in two patients (7.4%),6, 17 urethral orifice in one patient (3.7%)15 and perineum in one patient (3.7%).6 Prior sexual contact was reported in four patients (14.8%).4, 20, 22, 24 Punch biopsy was performed in five patients (18.5%).6, 7, 11, 14, 20 Most patients included in the individual case reports had blood counts (17 patients [62.9%]4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24) and serological testing (24 patients [88.8%]) performed.4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20, 22 Pathogens reported as targets of serological testing included herpes simplex virus (HSV), EBV, CMV, hepatitis A, B, C virus, (HAV, HBV, HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), chlamydia trachomatis, chlamydia pneumoniae, mumps, syphilis, parvovirus B 19 (PVB19), mycoplasma, toxoplasma gondii, influenza B and adenovirus. Tests for EBV were done in 24 patients (88.8%).6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20, 22 Prescribed medication or therapy included topical and systemic antibiotics in 17 patients (62.9%),5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24 topical and systemic cortisone in 10 patients (37.0%),7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19, 23, 24 analgesics in six patients (22.2%)5, 7, 15, 16, 17, 18 and surgical intervention (necrectomy) in one patient (3.7%).5 Ulcers resolved without sequelae in 23 patients (85.2%)4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23; resolved with sequelae (i.e. scars) in two patients (7.4%),12, 24 and had no reported outcome in two patients (7.4%.).18, 19 Ulcer recurred in only one patient (3.7%).23

Case series

The 33 patients in the case series ranged in age from 10 to 79 years.3 Aphthosis was mentioned in four patients (12.1%), but in none of these cases, localization to the oral mucosa was clearly defined. Flu‐like symptoms were reported in 17 patients (51.5%). A single ulcer was reported in 11 patients (33%). The labia minora and labia majora were affected in 10 patients (30.3%) and two patients (6%), respectively. Further localization was reported to the vestibule in 19 patients (57.6%), clitoris in one patient (3%) and interlabial sulcus in one patient (3%). Prior sexual contact was reported in more than 80% of patients in the case series, though it was not reported whether there might be a temporal connection. No punch biopsy was reported in the case series. Blood counts and serological testing were done in cases of severe systemic symptoms or delayed healing. Two positive EBV results were reported. No prescribed medications or outcomes were reported in the case series.

Algorithm for diagnosis and treatment

On the basis of our systematic review, we propose the following algorithm and define major and minor criteria for the standardized diagnosis of UVAL.

-

Major criteria:

-

Minor criteria:

-

o

Localization of ulcer at vestibule or labia minora

-

o

No sexual intercourse ever (i.e. patient is a virgin) or within the last 3 months

-

o

Flu‐like symptoms

-

o

Systemic infection within 2–4 weeks prior to onset of vulvar ulcer.

-

o

Table 5.

Recommended algorithm for exclusion of infectious diseases in order to identify UVAL

| Sexually transmitted infections |

|

| Other infectious conditions |

|

Table 6.

The most common diseases mimicking UVAL

| Disease | Aid to differentiate |

|---|---|

| Infectious diseases | |

| Herpes genitalis |

|

| Primary syphilis lesion |

|

| Ulcus molle (Chancroid) |

|

| Lymphogranuloma venereum |

|

| Non‐infectious systemic conditions | |

| Crohn's disease |

|

| Side effects of medication (e.g. methotrexate) |

|

| Topicals | Some patients may use inappropriate emollients |

| Behcet's disease |

|

| Bullous diseases |

|

| Traumatic cause | Sexual intercourse/mechanic manipulation/dermatitis factitia |

| Malignant tumours |

|

If both of the major criteria and at least two of the minor criteria apply to a case, then a diagnosis of UVAL is warranted.

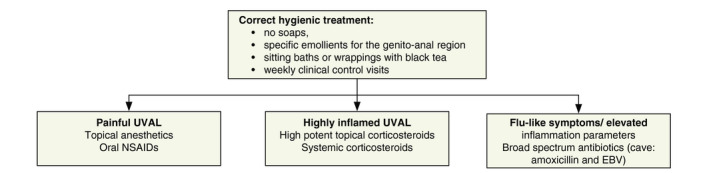

After exclusion of other infections and diseases (Tables 5 and 6) and after diagnosis of UVAL as just described, symptomatic treatment to facilitate healing is recommended (Fig. 2). Note, however, that healing can occur spontaneously within 2 weeks.3, 5 Correct hygienic treatment of the genital region should be explained by a healthcare professional.6 In patients with leucocytosis and elevated C‐reactive protein (CRP) levels, broad‐spectrum antibiotics should be considered. However, amoxicillin is contraindicated in the context of EBV infection. Topical disinfectants (e.g. polyvidone‐iodine bath) or anaesthetic gels (e.g. lidocaine) are recommended for patients suffering from painful lesions.2, 23 In severe cases, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs are useful for pain relief and anti‐inflammatory effects. In addition, high‐potency topical corticosteroids can be applied in patients with severe local inflammation.20, 23 A short course of systemic corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone 0.5–1.0 mg/kg for 7 days) is recommended only in patients of high need.5 A weekly follow‐up is recommended until the lesion(s) and symptoms improve,2 and re‐evaluation of laboratory parameters may be considered.

Figure 2.

Proposed treatment algorithm for UVAL.

Discussion

Our study's aim was to perform a systematic literature review of UVAL in order to formulate a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. A symptom‐based treatment algorithm based on our proposed major and minor criteria will improve the diagnosis and management of UVAL.

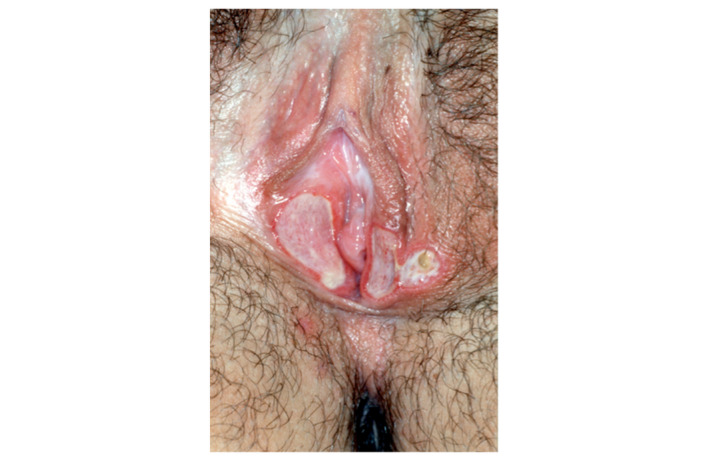

Ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz is a painful ulcer of unknown aetiology and acute onset in mainly virgins.3, 5, 8, 11, 21 Typically, UVAL presents as a solitary and large (>1 cm in diameter) lesion, though multiple and ‘kissing’ ulcers may also be seen (Fig. 3).2, 7 In our systematic review, a solitary ulcer was described in 10 patients, whereas multiple ulcers were described in 17 patients (including two lesions in six patients, three in six patients and ≥4 in five patients). This is consistent with the finding of Vieira‐Baptista et al.,3 who found multiple lesions to be more frequent (66.7% in their case series of 33 patients). The ulcers are typically deep with sharply demarcated borders and fibrinous coatings or greyish exudate.2, 5, 8, 9 One or more ulcers are mandatory for the definition of UVAL (proposed major criteria no 1: ‘Acute onset of one or more painful ulcerous lesion at the vulvar region’). Classical signs of inflammation may occur, including calor, rubor, tumour and dolour. Typically, UVAL ulcers occur on the labia minora (21/27; 77.7%), but might be found at other locations as well;2, 3 in the case series of 33 patients, ulcers were found most often on the vestibule (57.6%) and labia minora (30.3%).3 According to our review of the data, ulcer localization on the vestibule or labia minora might hint at UVAL and is therefore suggested as a minor criteria (‘Localization of ulcer at vestibule or labia minora’).

Figure 3.

UVAL: kissing ulcers, sharply demarcated boarders, fibrinous coatings.

Sexual case history (i.e. sexual intercourse ever and when) is most important in determining ulcer aetiology. Genital ulcers generally result from sexually transmitted infections including, in most cases, genital herpes and primary syphilitic lesion; however, they may also be due to non‐infectious diseases such as Morbus Behcet, or bullous diseases.2, 3, 25 Other sexually transmitted diseases involving ulcerative lesions include lymphogranuloma venereum (Chlamydia trachomatis L1‐L3), ulcus molle (H. ducreyi) and sexual trauma itself.2

In cases of recurrent ulcer, other diseases such as behcet's disease bullous and chronic inflammatory bowel disease should be excluded.2 Other non‐infectious diseases with the potential to cause mucosal ulcerations are aphthosis, hidradenitis suppurativa, pyoderma gangraenosum and malignant tumours as well as drug reactions.3, 5, 26 Since diagnosis of UVAL is based on exclusion of other possible causative conditions (which is of the utmost importance), we recommend this as major criteria no. 2 (‘Exclusion of infectious and non‐infectious causes for the ulcer’).

Ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz has been linked to various bacterial and viral infections; therefore, amplification techniques such as smears and serology are recommended to detect infections of EBV or mycoplasma pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, influenza virus, mumps, salmonella or PVB19.2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 13, 23, 27 The majority of publications reviewed for this systematic analysis, reported serological testing for at least some infectious diseases such HSV, EBV and syphilis (see Table 3). EBV was tested for in nearly all cases (24/27; 88.8%) but was found to be an active infection in only five patients. Chen and Plewig published a review and mentioned that juvenile gangraenous vasculitis of the scrotum might be the male counterpart to UVAL and EBV testing should be added in those cases.27

Moreover, an active infection was found in one case each for influenza B and adenovirus,19 mumps,4 CMV22 and salmonella parathyphii A.13 Furthermore, Vieira‐Baptista et al.3 reported a possible association between PVB19 and vulval ulcers and called for further investigation of PVB as a causative agent. Interestingly, there was a report that linked Lipschütz ulcer to an immunodeficiency in two girls with partial IgA deficiency,19 and the authors called for alertness concerning immunological mechanisms. Non‐gynaecological infections prior to the onset of UVAL seem to be found in a multitude of patients and are therefore suggested as a minor criteria (‘Systemic infection within the last 2–4 weeks prior to onset of vulvar ulcer’).

Ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz seems to be mainly a disease of the young. This is supported by our finding that the majority of patients in our systematic review were younger than 16 years (19/27; 70.3%) and did not report any prior sexual contact (22/27; 81.4%). In the case series of Vieira‐Baptista et al.,3 84.4% of patients were no longer virgins, but it was not declared how recently they might have had sexual intercourse. We recommend that the recent sexual activity status of a patient be used as a minor criteria (‘No sexual intercourse ever [i.e. subject is a virgin] or within the last 3 months is reported’).

Histopathology appears to be of no major importance in this disease, as the results seem to be non‐specific.3 However, if histopathology is performed, it should be done from the edge of the ulcer.5, 12, 20 Punch biopsy was done in few of the cases analysed (5/27; 18.5%),6, 7, 11, 14, 20 and results were also non‐specific.

Flu‐like symptoms, including fever, chills, fatigue or malaise, were reported in many of the individual cases (22/27; 81.5%) that we reviewed. This has been reported as well by others.2, 8, 11, 21 Vieira‐Baptista et al.3 reported that about 75.5% of patients in their case series had non‐gynaecological symptoms before ulcers appeared. The fact that systemic symptoms are present in the majority of patients therefore suggests another of our minor criteria (‘Flu‐like symptoms’). Evaluating blood cell count and other inflammation parameters can be helpful in deciding on further treatments such as systemic immunosuppression or antibiotics, especially in those suffering from flu‐like symptoms. We found that blood count was evaluated in 17 of 27 cases (62.9%).

In a descriptive study of 13 acute genital ulcers, Farhi et al.28 defined the following inclusion and exclusion criteria, which we discussed and further developed as criteria for UVAL. The major criteria proposed by Farhi et al. were (i) first flare of acute genital ulcer; (ii) age younger than 20 years; (iii) absence of sexual contact during the past 3 months; (iv) absence of immunodeficiency; and (v) acute course of the genital ulcer. Minor criteria were (i) 1 or multiple deep, well‐delimited, painful ulcers, with a necrotic and/or fibrinous centre or (ii) ulcers with a ‘kissing pattern’. Patients were excluded if they had (i) history of genital aphthosis or sexually transmitted disease (STD); (ii) clinical or microbiological evidence of genital herpes or another STD; and (iii) immunodeficiency.28 On the basis of our systematic review and inspired by Farhi et al., we recommend using the above adapted and defined major and minor criteria for the standardized diagnosis of UVAL, as well as the therapeutic algorithm for standardized workup. This is in line with Chen and Plewig, who have just recently stated that the diagnosis of UVAL has to include the whole spectrum of the disease and not only its clinical picture.27

In conclusion, this report provides several helpful tools for more rapid diagnosis and symptomatic treatment of the severe and painful genital ulcer disease UVAL. These tools include capture of an accurate medical history, a standardized workup and the use of newly proposed major and minor criteria.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding source

None.

References

- 1. Lipschütz B. Über eine eigenartige Geschwulstform des weiblichen Genitales (Ulcus vulave acutum). Arch Dermatol Syph 1913; 114: 363–395. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huppert JS. Lipschutz ulcers: evaluation and management of acute genital ulcers in women. Dermatol Ther 2010; 23: 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vieira‐Baptista P, Lima‐Silva J, Beires J, Martinez‐de‐Oliveira J. Lipschütz ulcers: should we rethink this? An analysis of 33 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016; 198: 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chanal J, Carlotti A, Laude H, Wallet‐Faber N, Avril MF, Dupin N. Lipschütz genital ulceration associated with mumps. Dermatology 2010; 221: 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Delgado‐García S, Palacios‐Marqués A, Martinez‐Escoriza JC, Martin‐Bayon TA. Acute genital ulcers. BMJ Case Rep 2014; 2014: bcr2013202504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burguete Archel E, Ruiz Goikoetxea M, Recari Elizalde E, Beristain Rementería X, Gómez Gómez L, Iceta Lizarraga A. Lipschütz ulcer in a 17‐month‐old girl: a rare manifestation of Epstein‐Barr primoinfection. Eur J Pediatr 2013; 172: 1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sárdy M, Wollenberg A, Niedermeier A, Flaig MJ. Genital ulcers associated with Epstein Barr virus infection (ulcus vulvae acutum). Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91: 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Truchuelo MT, Vano‐Galván S, Alcántara J, Pérez B, Jaén P. Lipschütz ulcers in twin sisters. Pediatr Dermatol 2012; 29: 370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Svedman C, Holst R, Johnsson A. Ulcus vulvae acutum, a rare diagnosis to keep in mind. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004; 115: 104–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group . Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernandez‐Nunez A, Cordoba S, Romero‐Mate A, Minano R, Sanz T, Borbujo J. Lipschütz ulcers–four cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2008; 25: 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Török L, Domján K, Faragó E. Ulcus vulvae acutum. Cutis 2000; 65: 387–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pelletier F, Aubin F, Puzenat E et al Lipschütz genital ulceration: a rare manifestation of parathyphoid fever. Eur J Dermatol 2003; 13: 297–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fremlin AG, Irani S, Loffeld A. It's not always that simplex. Arch Dis Child 2018; 103: 987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolters V, Hoogslag I, van't Wout J, Boers K. Lipschütz ulcers: a rare diagnosis in women with vulvar ulceration. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 130: 420–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mourinha V, Costa A, Urzal C, Guerreiro F. Lipschütz ulcers: uncommon diagnosis of vulvar ulcerations. BMJ Case Rep 2016; 2016: bcr2015214338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. García JG, Pavón BM, Martín LM, Martínez BF, Bornielle CM, Caro FA. Lipschütz ulcer: a cause of misdiagnosis when suspecting child abuse. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34: 1326.e1‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haidari G, MacMahon E, Tong CY, White JA. Genital ulcers: it is not always simplex. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26: 72–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinyo A, Nagy N, Olah J, Kemeny L, Bata‐Csörgö Z. Ulcus vulvae acutum Lipschütz in two young female patients. Eur J Dermatol 2014; 24: 361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brinca A, Canelas MM, Carvalho MJ, Vieira R, Figueiredo A. Lipschütz ulcer (ulcus vulvae acutum): a rare cause of genital lesion. An Bras Dermatol 2012; 87: 622–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alés‐Fernandes M, Rodriguez‐Pichardo A, Garcia‐Bravo B, Ferrandiz‐Pulido L, Camacho‐Martinez FM. Three cases of Lipschutz vulval ulceration. Int J STD AIDS 2010; 21: 375–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin JM, Godoy R, Calduch L, Villalon G, Jordá E. Lipschütz acute vulval ulcers associated with primary cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Dermatol 2008; 25: 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wetter DA, Bruce AJ, MacLaughin KL, Rogers RS 3rd. Ulcus vulvae acutum in a 13‐year‐old girl after influenza A infection. Skinmed 2008; 7: 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trcko K, Belic M, Miljković J. Ulcus vulvae acutum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2007; 16: 174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roett MA, Mayor MT, Uduhiri KA. Diagnosis and management of genital ulcers. Am Fam Physician 2012; 85: 254–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirshen C, Edwards L. Noninfectious genital ulcers. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2015; 34: 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen W, Plewig G. Lipschütz genital ulcer revisited: is juvenile gangrenous vasculitis of the scrotum the male counterpart? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 1660–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Farhi D, Wendling J, Molinari E et al Non‐sexually related acute genital ulcers in 13 pubertal girls: a clinical and microbiological study. Arch Dermatol 2009; 145: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]