Summary

Interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) plays pivotal roles in controlling bacterial infections and is produced after the processing of pro‐IL‐1β by caspase‐1, which is activated by the inflammasome. In addition, caspase‐1 cleaves the cytosolic protein, gasdermin‐D (GSDMD), whose N‐terminal fragment subsequently forms a pore in the plasma membrane, leading to the pyroptic cell‐death‐mediated release of IL‐1β. Living cells can also release IL‐1β via GSDMD pores or other unconventional secretory pathways. However, the precise mechanisms are poorly defined. Here, we show that lipoproteins from Mycoplasma salivarium (MsLP) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MpLP) and an M. salivarium‐derived lipopeptide (FSL‐1), which are activators of the nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, induce IL‐1β release from mouse bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) without inducing cell death. The levels of IL‐1β release induced by MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 were more than 100 times lower than those induced by the canonical NLRP3 activator nigericin. The IL‐1β release‐inducing activities of MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 were not attenuated in BMMs from GSDMD‐deficient mice. Furthermore, both active caspase‐1 and cleaved GSDMD were detected in response to transfection of FSL‐1 into the cytosol of BMMs, but the release of IL‐1β was unaffected by GSDMD deficiency. Meanwhile, punicalagin, a membrane‐stabilizing agent, drastically down‐regulated the release of IL‐1β in response to FSL‐1. These results suggest that mycoplasmal lipoprotein/lipopeptide‐induced IL‐1β release by living macrophages is not mediated via GSDMD but rather through changes in membrane permeability.

Keywords: gasdermin D, interleukin‐1β, mycoplasmal lipopeptide, mycoplasmal lipoproteins, plasma membrane permeabilization

Mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptide induced the release of interleukin‐1β by live murine bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages. Changes in membrane permeability, but not pyroptosis and gasdermin D pores, played important roles in the expression of the activities.

Abbreviations

- ASC

adaptor protein apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase‐recruitment domain

- BMM

bone‐marrow‐derived macrophage

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GSDMD

gasdermin D

- GSDME

gasdermin E

- IL‐1β

interleukin‐1β

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MpLP

Mycoplasma. pneumoniae lipoproteins

- MsLP

Mycoplasma salivarium lipoproteins

- NLR

nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor

- NLRP3

nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulphate

- vol

volume

- wt

weight

- WT

wild‐type

Introduction

Interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) plays important roles in controlling bacterial infections by inducing inflammation and recruiting and activating immune cells. 1 Unlike most cytokines, IL‐1β lacks a signal peptide and is therefore not secreted through the conventional endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi protein secretion route, 2 although the precise mechanisms by which it is secreted are poorly understood.

Interleukin‐1β is produced and released into the extracellular space as a result of the processing of its inactive precursor, pro‐IL‐1β, by caspase‐1, which is activated by the intracellular multiprotein complex known as the inflammasome. Canonical inflammasomes typically consist of a nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor (NLR), adaptor protein apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase‐recruitment domain (ASC) and procaspase‐1. Among the several types of inflammasomes, the NLR family pyrin domain containing‐3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is the most characterized and is activated in response to a broad spectrum of stimuli including microbial products. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Moreover, there are non‐canonical inflammasomes that are activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram‐negative bacteria in the cytoplasm, which activate murine caspase‐11 (i.e. human caspase‐4 and caspase‐5). 9 , 10

Caspase‐1 and caspase‐11/4/5, which are activated by canonical and non‐canonical inflammasomes, respectively, trigger a pro‐inflammatory form of cell death called pyroptosis, which releases bioactive IL‐1β into the extracellular space. 11 , 12 These caspases were recently shown to cleave the cytosolic protein gasdermin D (GSDMD). Upon cleavage, the N‐terminal fragment of GSDMD forms a pore in the plasma membrane that alters osmotic pressure, which leads to cell lysis and the rapid release of cellular contents. Therefore, pyroptosis has been redefined as GSDMD‐mediated programmed necrosis. 8 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

Living cells have also been reported to release IL‐1β. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 The cells that release IL‐1β in the absence of cell death are considered hyperactive cells. 31 For example, a microbial hyperactivating stimulus, the N‐acetyl glucosamine component of bacterial peptidoglycan, induces NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated IL‐1β release from living macrophages. 24 , 27 Furthermore, IL‐1β secretion from living cells can be promoted by GSDMD pores 27 , 28 or via mechanisms independent of GSDMD. 29 , 32 Furthermore, the secretory mechanism of IL‐1β was recently shown to depend on alteration of membrane permeability. 29 , 33 , 34

We previously found that membrane‐bound lipoproteins from Mycoplasma salivarium (MsLP) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MpLP) as well as FSL‐1, a lipopeptide derived from M. salivarium, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome to produce IL‐1β in murine bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs). 35 However, the secretory mechanisms involved remain elusive.

Here, we show that these mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides induce IL‐1β release by non‐pyroptosing living BMMs through mechanisms that are dependent on plasma membrane permeabilization but not GSDMD.

Materials and methods

Reagents

FSL‐1, a diacylated lipopeptide derived from M. salivarium, was synthesized as previously described. 36 Fluorescein isothiocyanate‐conjugated FSL‐1 (FITC‐FSL‐1) was purchased from EMC Microcollections GmbH (Tübingen, Germany). Ultrapure Escherichia coli LPS was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Nigericin and punicalagin were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Glycine was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Mycoplasmas and culture conditions

Mycoplasma salivarium ATCC23064 and M. pneumoniae ATCC15492 were grown in pleuropneumonia‐like organism broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 20% [volume/volume (vol/vol)] horse serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 1% [weight (wt)/vol] yeast extract (Difco), 1% (wt/vol) l‐arginine hydrochloride for M. salivarium or 1% (wt/vol) d‐glucose for M. pneumoniae, and 1000 units/ml penicillin G.

Cultures were incubated at 37° and centrifuged at 15 000 g for 15 min at a late log‐phase. The cell pellets were washed three times with sterilized phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), suspended in PBS to make aliquots, and then stored at −80°. Protein concentration was determined using a DC Protein Assay kit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lipoprotein preparation by Triton X‐114 phase separation

Mycoplasma salivarium and M. pneumoniae cells were treated with Triton X‐114 to extract lipoproteins as previously described. 37 The Triton X‐114 phase was collected, treated with methanol to precipitate lipoproteins, suspended in sterile PBS and used for stimulation. The lipoproteins prepared from M. salivarium and M. pneumoniae were designated MsLP and MpLP, respectively. Protein concentration was determined by using a DC Protein Assay kit (Bio‐Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mice

Wild‐type C57BL/6 (WT) mice were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained in specific pathogen‐free conditions at the Animal Facility of Hokkaido University. GSDMD‐deficient (GSDMD−/−) mice of the same genetic background 38 were kindly provided by Dr Toshihiko Shiroishi (RIKEN BioResource Research Centre) and maintained in specific pathogen‐free conditions at the animal facility of Kanazawa University. All experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations of the Animal Care and Use Committees of Hokkaido University (14‐0066, 19‐0059) and Kanazawa University (AP‐173853).

Cell culture of BMMs

Bone marrow cells were prepared from the femurs and tibias of GSDMD−/− mice at Kanazawa University and sent to Hokkaido University for analysis. Bone marrow cells from the femurs and tibias of WT mice were prepared at Hokkaido University.

The bone marrow cells were cultured in 10‐cm, plastic, non‐tissue‐culture Petri dishes in RPMI‐1640 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and cell‐conditioned medium (i.e., culture supernatants derived from L929 fibroblast cells). After 7–9 days of culture, macrophages that loosely adhered to the dishes were harvested by using cold PBS and then used as BMMs.

IL‐1 β measurement

Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages from WT or GSDMD−/− mice were added to a 24‐well plate at 4 × 105 cells/well in 500 μl RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and incubated at 37° for 4 hr with 10 ng/ml ultrapure E. coli LPS. The cells were subsequently resuspended in 300 μl RPMI‐1640 basal medium and incubated at 37° with MsLP or MpLP (0, 0·4 or 4 μg/ml protein), FSL‐1(0, 10 or 100 nm), or nigericin (5 µm; a representative pyroptotic NLRP3 inflammasome stimulator used as a positive control). Incubation times are indicated in the figures and figure legends. IL‐1β in cell‐culture supernatants was quantified using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for IL‐1β (OptEIA™ SET Mouse IL‐1β; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

LDH release assay

The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from cells into culture supernatants was measured using a CytoTox 96 kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytotoxicity was calculated against the maximum release of LDH, which was obtained by cell lysis with 0·09% Triton X‐100. The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated as LDH released in [tested sample (A490)/maximum LDH release (A490)] × 100.

FSL‐1 transfection, immunoblot analysis and ELISA

Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages from WT mice were added to a six‐well plate at 1·6 × 106 cells/well in 2 ml RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% FBS and incubated at 37° for 4 hr with 10 ng/ml ultrapure E. coli LPS. The cells were washed with RPMI‐1640 basal medium and resuspended in 900 μl medium. Next, 100 μl FSL‐1 solution (1 μm) dissolved in 20 mm HEPES buffer was mixed with 1 μl PULSin reagent (Polyplus‐Transfection, Illkirch, France) and added to the appropriate wells after 15 min of incubation. After 5 hr of incubation at 37°, the cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer [25 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7·5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% (w/v) IGEPAL® CA‐630 (Sigma‐Aldrich) and complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany)] and combined with the supernatant precipitated with 6% Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA).

Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages from WT mice were added to a six‐well plate at 1·6 × 106 cells/well in 2 ml RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% FBS and incubated at 37° for 4 hr with 10 ng/ml ultrapure E. coli LPS. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml RPMI‐1640 basal medium and incubated with 5 μm nigericin at 37° for 1 hr. The cells were then lysed in cell lysis buffer and combined with the supernatant precipitated with 6% TCA. The samples were treated with sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) sample buffer and submitted to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio‐Rad) and reacted with rabbit anti‐mouse caspase‐1 antibody (sc‐514; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti‐mouse GSDMD antibody (ab209845; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), goat anti‐mouse IL‐1β antibody (AF‐401; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and anti‐β‐actin (AC‐15; Sigma‐Aldrich).

To assess the release of IL‐1β, BMMs from WT or GSDMD−/− mice were added to a 24‐well plate at 4 × 105 cells/well in 500 μl RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and incubated with 10 ng/ml ultrapure E. coli LPS at 37° for 4 hr. The cells were washed with RPMI1640 basal medium and resuspended in 270 μl medium. Then, 30 μl FSL‐1 solution (1 μm) dissolved in 20 mm HEPES buffer was mixed with 0·3 μl PULSin reagent and added to the appropriate wells after 15 min incubation. After the indicated times of incubation at 37°, the concentration of IL‐1β in the cell‐culture supernatants was measured using an ELISA kit (BD OptEIA™ Set Mouse IL‐1β; BD Biosciences).

Localization of FSL‐1 in the cytosol

Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages from WT mice were added to a six‐well plate at 8 × 105 cells/well in 2 ml RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% FBS and incubated at 37° for 4 hr with 10 ng/ml ultrapure E. coli LPS. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml RPMI‐1640 basal medium and incubated at 37° for 2 hr with 2 μg/ml of FITC‐FSL‐1 in the absence or the presence of punicalagin (25 μm). After being washed three times with PBS, the cells were fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), and then washed three times with PBS containing 10 mm glycine and sealed in SlowFade™ Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR). Confocal images were taken by a confocal laser scanning microscopy system (Nikon A1 and Ti‐E) equipped with a Plan Apo VC 60× objective lens (NA 1.40; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t‐test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0·05.

Results

IL‐1 β release by BMMs in response to mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides is independent of cell death

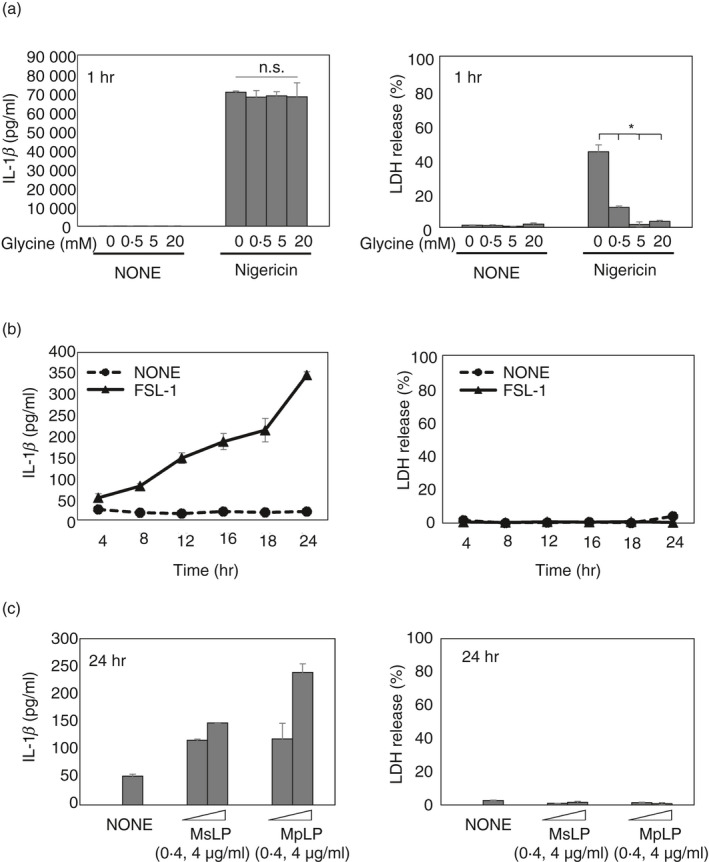

We previously showed that MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 activate the NLRP3 inflammasome to produce IL‐1β in BMMs. 35 Inflammasome‐dependent cell death, i.e. pyroptosis, is a mechanism that involves IL‐1β release into the extracellular space. 11 , 12 Therefore, to determine if MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 induces pyroptosis in BMMs, the LDH released into the culture supernatants was quantified. Nigericin, a representative pyroptotic NLRP3 inflammasome stimulator, was used as a positive control. Concordant with previous studies, 27 , 29 1 hr of stimulation with LPS‐primed BMMs with nigericin resulted in the release of extremely large quantities of IL‐1β as well as cell death (Fig. 1a). The cell death was not essential for the release of IL‐1β, because the cytoprotective agent glycine down‐regulated the LDH release in a dose‐dependent manner but not the IL‐1β release. However, FSL‐1 induced less release of IL‐1β, although the quantities increased significantly in a linear fashion up to 24 hr after stimulation without inducing cell death (Fig. 1b). Like FSL‐1, MsLP and MpLP also induced the release of similar quantities of IL‐1β without inducing cell death (Fig. 1c). Therefore, in the subsequent experiments, the supernatants of MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1‐treated BMMs after LPS priming were examined at 24 hr unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1.

Mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides induce interleukin‐β (IL‐1β) release by bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) independent of cell death. (a) BMMs from wild‐type (WT) mice were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by glycine (0, 0·5, 5 or 20 mm) with nigericin (5 μm) for 1 hr. Quantification of total IL‐1β and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture supernatant. (b) BMMs from WT mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by FSL‐1 (100 nm) for the indicated times. Quantification of total IL‐1β and LDH released into the culture supernatant. (c) BMMs from WT mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by Mycoplasma salivarium or Mycoplasma pneumoniae lipoproteins (MsLP and MpLP, respectively; 0, 0·4 or 4 μg/ml protein) for 24 hr. Quantification of total IL‐1β and LDH released into the culture supernatant. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of duplicate assays of a representative experiment. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained. Student’s t‐test. n.s., not significant; *P < 0·05.

These results suggest that stimulation with nigericin rapidly induces substantial IL‐1β release by BMMs with the induction of pyroptosis, whereas stimulation with MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 slowly induces IL‐1β release without inducing cell death. Therefore, the next experiment was performed to determine how MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 induce IL‐1β release by living macrophages.

GSDMD is not required for the IL‐1β release by BMMs in response to mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides

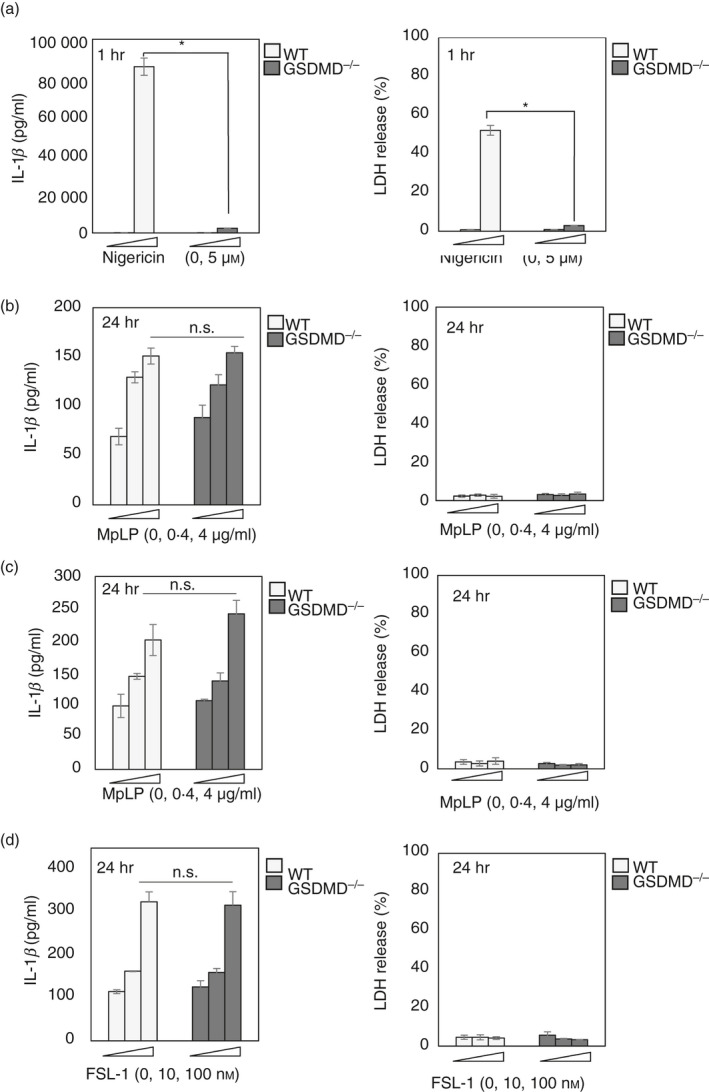

In addition to cleaving IL‐1 family cytokines, active caspase‐1 cleaves the cytosolic protein GSDMD. Upon cleavage, the N‐terminal fragment of GSDMD forms a pore in the plasma membrane, which leads to induction of pyroptosis. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate that under certain conditions, GSDMD pores do not induce pyroptosis but rather promote IL‐1β secretion from living cells. 27 , 28 Therefore, to investigate whether the release of IL‐1β by living BMMs in response to MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 is mediated via GSDMD pores, IL‐1β release was examined in BMMs from WT and GSDMD−/− mice. Nigericin was used as a control because it triggers the GSDMD‐dependent release of IL‐1β from BMMs. 27 , 28 Similar to previous findings, in GSDMD−/− BMMs, nigericin did not induce IL‐1β or LDH release (Fig. 2a). However, IL‐1β release induced by MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 was not attenuated in GSDMD−/− BMMs (Fig. 2b–d). Furthermore, MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 did not induce LDH release from WT or GSDMD−/− BMMs (Fig. 2b–d). These results collectively suggest that GSDMD is not required for the release of IL‐1β by BMMs in response to mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides.

Figure 2.

Mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptide induce interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) release by bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) independent of gasdermin‐D (GSDMD). (a) BMMs from wild‐type (WT) or GSDMD−/− mice were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by nigericin (5 μm) for 1 hr. Quantification of total IL‐1β and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture supernatant. (b–d) BMMs from WT or GSDMD−/− mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by Mycoplasma salivarium or Mycoplasma pneumoniae lipoproteins (MsLP or MpLP, respectively; 0, 0·4 or 4 μg/ml protein) or FSL‐1 (an M. salivarium‐derived lipopeptide; 0, 10 or 100 nm). Quantification of total IL‐1β and LDH released into the culture supernatant. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of (a) duplicate or (b–d) triplicate assays of a representative experiment. All experiments were repeated at least three times, and similar results were obtained. Student’s t‐test. n.s., not significant; *P < 0·05.

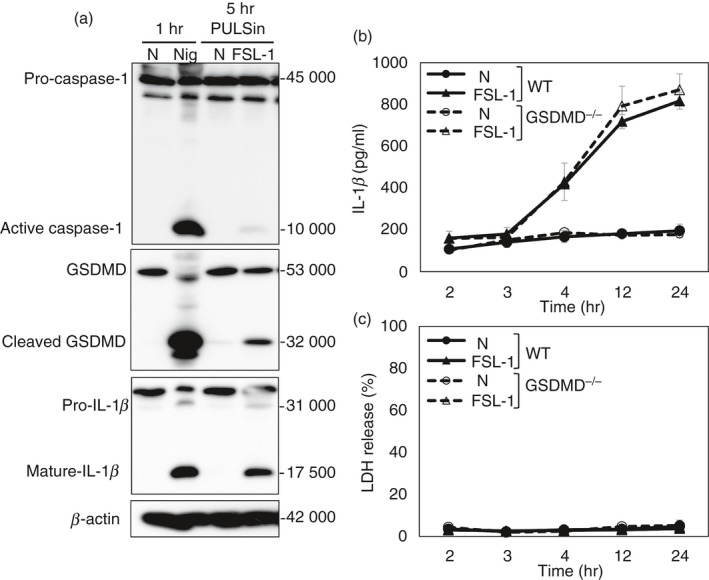

FSL‐1 transfection by PULSin cleaves GSDMD

Gasdermin‐D is a substrate of both caspase‐1 and caspase‐11/4/5, which are activated by the inflammasome. 13 , 14 Because the processing of pro‐IL‐1β in response to MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 is dependent on caspase‐1 after the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, 35 whether GSDMD is cleaved by caspase‐1 activated by MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 was determined. Caspase‐1 activation and GSDMD cleavage in cell lysates and culture supernatants were examined by Western blotting using anti‐caspase‐1 and anti‐GSDMD antibodies, respectively. Consistent with previous reports, 14 , 30 , 34 , 39 , 40 nigericin activated caspase‐1 (10 000 MW) and cleaved GSDMD (32 000 MW; Fig. 3a). However, the band of active caspase‐1 was not detected in FSL‐1‐treated BMMs under the assay conditions used (data not shown). This was probably attributable to the level of the IL‐1β‐inducing activity and the detection sensitivity of Western blotting. We previously found that the artificial delivery of FSL‐1 into the cytosol of BMMs using the PULSin protein transfection reagent enhances the IL‐1β‐inducing activity. 35 Accordingly, under this assay condition, both active caspase‐1 and cleaved GSDMD as well as IL‐1β (17 500 MW) were detected (Fig. 3a). Therefore, to clarify the involvement of GSDMD cleavage in the induction of IL‐1β release by FSL‐1, the IL‐1β and LDH released into the culture supernatants in both WT and GSDMD−/− BMMs after transfection with FSL‐1 at several points in time were quantified. GSDMD deficiency did not affect IL‐1β release in response to FSL‐1 transfection (Fig. 3b). Moreover, LDH was released from neither WT nor GSDMD−/− BMMs (Fig. 3c). Taken together, these results indicate that GSDMD‐independent mechanisms contribute to the IL‐1β release from BMMs in response to mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides, although they can activate caspase‐1 and cleave GSDMD.

Figure 3.

FSL‐1 transfection by PULSin cleaves gasdermin‐D (GSDMD). Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr before transfection with FSL‐1 or stimulation with nigericin. BMMs from wild‐type (WT) mice were transfected with FSL‐1 (100 nm) by PULSin or stimulated with nigericin (Nig) (5 μm) and then incubated for the indicated times. (a) Combined supernatants and cell lysates were analysed for activated caspase‐1, GSDMD, interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) and β‐actin by immunoblot analysis. (b, c) BMMs from WT or GSDMD−/− mice were transfected with FSL‐1 (100 nm) by PULSin and then incubated for the indicated times. Quantification of total (b) IL‐1β and (c) LDH released into the culture supernatant. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate assays of a representative experiment. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained.

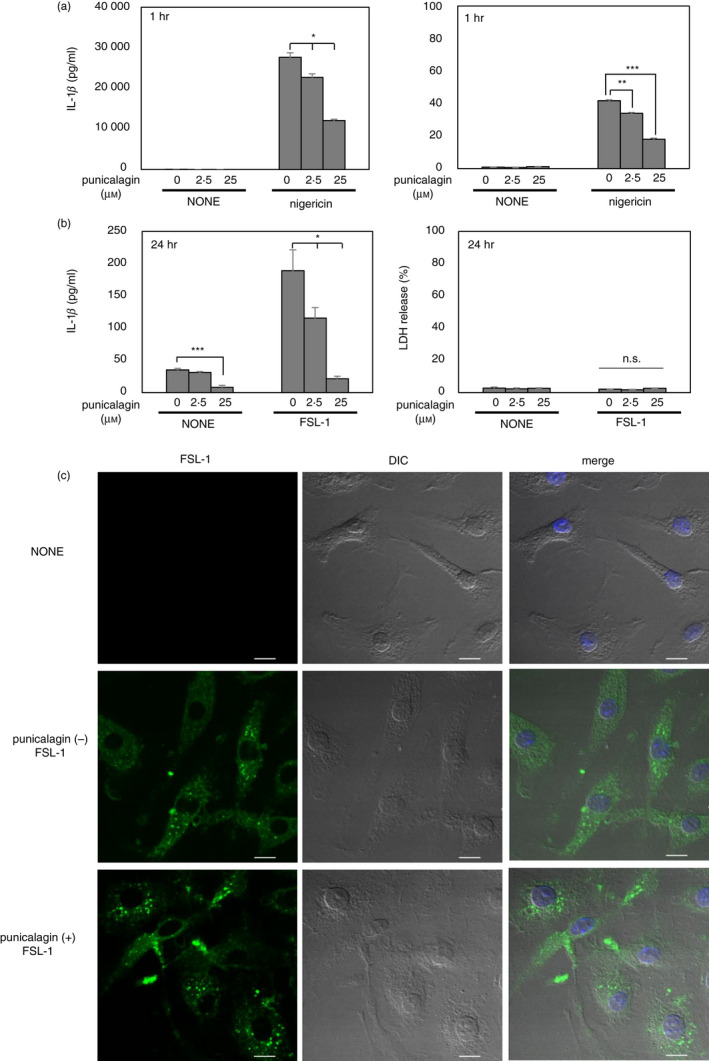

Mycoplasmal lipopeptide‐induced IL‐1β release is dependent on plasma membrane permeabilization

Changes in plasma membrane permeability were recently shown to be required for IL‐1β release by both pyroptotic and living cells. 29 , 33 , 34 Punicalagin is reported to stabilize plasma membrane lipids and consequently inhibits changes in membrane permeability, leading to the blockade of IL‐1β release. 33 Herein, punicalagin down‐regulated nigericin‐induced IL‐1β and LDH release from BMMs in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 4a), as previously reported. 29 , 33 , 34 Furthermore, punicalagin down‐regulated IL‐1β release in response to FSL‐1 in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 4b). To rule out the possibility that the down‐regulated IL‐1β release was due to the reduction of FSL‐1 uptake into the cytosol of BMMs by punicalagin, which is an important process leading to the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, 35 experiments were carried out to determine whether punicalagin down‐regulated internalization of FSL‐1. BMMs were incubated with FITC‐labelled FSL‐1 in the absence or presence of punicalagin and it was found that punicalagin had no effects on FSL‐1 uptake by BMMs (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that changes in membrane permeability play important roles in IL‐1β release from living BMMs.

Figure 4.

Mycoplasmal lipopeptide‐induced interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β) release is dependent on plasma membrane permeabilization. (a) Bone‐marrow‐derived macrophages (BMMs) from wild‐type (WT) mice were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by punicalagin (0, 2·5,or 25 μm) with nigericin (5 μm) for 1 hr. Quantification of total IL‐1β and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the culture supernatant. (b) BMMs from WT mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr, followed by punicalagin (0, 2·5 or 25 μm) with FSL‐1 (100 nm) for 24 hr. Quantification of total IL‐1β and LDH released into the culture supernatant. (c) BMMs from WT mice were stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 hr and then cultured with or without (NONE) 2 μg/ml of FITC‐FSL‐1 in the absence (−) or the presence (+) of punicalagin (25 μm). After incubation for 2 hr, the cells were fixed. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Samples were observed using a confocal microscope. FITC‐FSL‐1 (green) and differential interference contrast (DIC) are shown separately. The merged images with FITC‐FSL‐1, DAPI and DIC are also shown. Scale bar indicates 10 μm. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of (a) duplicate or (b) triplicate assays of a representative experiment. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained. Student’s t‐test. n.s., not significant; *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Discussion

Although various bacterial stimuli can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome to produce IL‐1β, cell‐fate outcomes are complicated, and there might not be a unified pathway that causes IL‐1β release. Some bacterial stimuli, such as nigericin, induce IL‐1β release via pyroptotic cell death, whereas others, such as peptidoglycan, induce a hyperactivated state in living cells whereby IL‐1β is released through GSDMD pores. 27 The present study shows that mycoplasmal lipoproteins (i.e. MsLP and MpLP) and a lipopeptide (i.e. FSL‐1) induce the release of IL‐1β by murine BMMs without inducing cell death (Fig. 1b,c). Therefore, we thought it possible that they are hyperactivating stimuli to murine BMMs. However, these mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides induced IL‐1β release by living murine BMMs independent of GSDMD pores (Fig. 2b–d).

As such, the mechanisms that mediate IL‐1β release independent of GSDMD remain poorly understood. Nevertheless, Monteleone et al. recently showed that slow IL‐1β release does not require GSDMD, whereas rapid IL‐1β release indeed requires GSDMD. 29 They demonstrated that pro‐IL‐1β cleavage by caspase‐1 removes the negatively charged pro‐piece, allowing positively charged mature IL‐1β to relocate from the cytosol to negatively charged phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate‐enriched plasma membrane projections and surface ruffles via electrostatic interaction, which leads to the slow release of IL‐1β. In the present study, MsLP, MpLP and FSL‐1 slowly induced IL‐1β release independent of GSDMD over a long period of time (Figs 1b,c and 2b–d). Therefore, the IL‐1β release induced by MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 is probably due to the slow release mechanism described above. Indeed, the membrane‐stabilizing agent punicalagin drastically down‐regulated the IL‐1β release in response to FSL‐1 (Fig. 4b).

Recent studies have also shown that gasdermin‐E (GSDME) is proteolytically activated by caspase‐3 during apoptosis, and its N‐terminal fragment forms a pore in the plasma membrane, which causes secondary necrosis/pyroptosis and the release of IL‐1β. 41 , 42 In fact, we have previously reported that mycoplasmal lipoproteins induce caspase‐3 activation, which was assessed by cleavage of poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase, a substrate of caspase‐3 in lymphocytic and monocytic cell lines. 43 , 44 , 45 Therefore, it is likely that the IL‐1β release induced by MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 might be mediated through GSDME pores. However, at present, it is unknown whether GSDME pores facilitate IL‐1β release from living cells in the hyperactivated state. Further studies are in progress in our laboratories to determine whether MsLP, MpLP or FSL‐1 induce GSDME pores in living BMMs.

Hence, a more modest abundance and more continuous release of IL‐1β from living macrophages in response to mycoplasmal lipoproteins/lipopeptides, compared with pyroptotic cells, might facilitate chronic and persistent inflammation in mycoplasma‐infected tissue.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Toshihiko Shiroishi (RIKEN BioResource Research Centre) for generously providing GSDMD‐deficient mice. AS and KS designed the study; AS performed the experiments; AS, KT, T Suda, TI, AH, T Suzuki, and KS analysed the data; KT and T Suda prepared bone marrow cells from GSDMD−/− mice; and AS and KS wrote the paper. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP19K10066 and JP16H06280. We would like to thank the Nikon Imaging Centre at Hokkaido University for technical support.

Senior author: Ken‐ichiro Shibata

References

- 1. Garlanda C, Dinarello CA, Mantovani A. The interleukin‐1 family: back to the future. Immunity 2013; 39:1003–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubartelli A, Cozzolino F, Talio M, Sitia R. A novel secretory pathway for interleukin‐1β, a protein lacking a signal sequence. EMBO J 1990; 9:1503–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mariathasan S, Monack DM. Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:229–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2012; 28:137–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13:397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. von Moltke J, Ayres JS, Kofoed EM, Chavarria‐Smith J, Vance RE. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:73–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:407–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J et al Non‐canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase‐11. Nature 2011; 479:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li P et al Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 2014; 514:187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monteleone M, Stow JL, Schroder K. Mechanisms of unconventional secretion of IL‐1 family cytokines. Cytokine 2015; 74:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S et al Caspase‐11 cleaves gasdermin D for non‐canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 2015; 526:666–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H et al Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015; 526:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aglietti RA, Estevez A, Gupta A, Ramirez MG, Liu PS, Kayagaki N et al GsdmD p30 elicited by caspase‐11 during pyroptosis forms pores in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113:7858–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi J et al Pore‐forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 2016; 535:111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H et al Inflammasome‐activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 2016; 535:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sborgi L, Ruhl S, Mulvihill E, Pipercevic J, Heilig R, Stahlberg H et al GSDMD membrane pore formation constitutes the mechanism of pyroptotic cell death. EMBO J 2016; 35:1766–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shi J, Gao W, Shao F. Pyroptosis: gasdermin‐mediated programmed necrotic cell death. Trends Biochem Sci 2017; 42:245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Caspase‐8 blocks kinase RIPK3‐mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity 2013; 38:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen KW, Gross CJ, Sotomayor FV, Stacey KJ, Tschopp J, Sweet MJ et al The neutrophil NLRC4 inflammasome selectively promotes IL‐1β maturation without pyroptosis during acute Salmonella challenge. Cell Rep 2014; 8:570–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conos SA, Lawlor KE, Vaux DL, Vince JE, Lindqvist LM. Cell death is not essential for caspase‐1‐mediated interleukin‐1β activation and secretion. Cell Death Differ 2016; 23:1827–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaidt MM, Ebert TS, Chauhan D, Schmidt T, Schmid‐Burgk JL, Rapino F et al Human monocytes engage an alternative inflammasome pathway. Immunity 2016; 44:833–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolf AJ, Reyes CN, Liang W, Becker C, Shimada K, Wheeler ML et al Hexokinase is an innate immune receptor for the detection of bacterial peptidoglycan. Cell 2016; 166:624–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diamond CE, Leong KWK, Vacca M, Rivers‐Auty J, Brough D, Mortellaro A. Salmonella typhimurium‐induced IL‐1 release from primary human monocytes requires NLRP3 and can occur in the absence of pyroptosis. Sci Rep 2017; 7:6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zanoni I, Tan Y, Di Gioia M, Springstead JR, Kagan JC. By capturing inflammatory lipids released from dying cells, the receptor CD14 induces inflammasome‐dependent phagocyte hyperactivation. Immunity 2017; 47:697–709.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evavold CL, Ruan J, Tan Y, Xia S, Wu H, Kagan JC. The Pore‐forming protein gasdermin D regulates interleukin‐1 secretion from living macrophages. Immunity 2018; 48:35–44.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heilig R, Dick MS, Sborgi L, Meunier E, Hiller S, Broz P. The Gasdermin‐D pore acts as a conduit for IL‐1β secretion in mice. Eur J Immunol 2018; 48:584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monteleone M, Stanley AC, Chen KW, Brown DL, Bezbradica JS, von Pein JB et al Interleukin‐1β maturation triggers its relocation to the plasma membrane for gasdermin‐D‐dependent and ‐independent secretion. Cell Rep 2018; 24:1425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carty M, Kearney J, Shanahan KA, Hams E, Sugisawa R, Connolly D et al Cell survival and cytokine release after inflammasome activation is regulated by the toll‐IL‐1R protein SARM. Immunity 2019; 50:1412–24.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zanoni I, Tan Y, Di Gioia M, Broggi A, Ruan J, Shi J et al An endogenous caspase‐11 ligand elicits interleukin‐1 release from living dendritic cells. Science 2016; 352:1232–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baroja‐Mazo A, Compan V, Martin‐Sanchez F, Tapia‐Abellan A, Couillin I, Pelegrin P. Early endosome autoantigen 1 regulates IL‐1β release upon caspase‐1 activation independently of gasdermin D membrane permeabilization. Sci Rep 2019; 9:5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin‐Sanchez F, Diamond C, Zeitler M, Gomez AI, Baroja‐Mazo A, Bagnall J et al Inflammasome‐dependent IL‐1β release depends upon membrane permeabilisation. Cell Death Differ 2016; 23:1219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tapia VS, Daniels MJD, Palazon‐Riquelme P, Dewhurst M, Luheshi NM, Rivers‐Auty J et al The three cytokines IL‐1β, IL‐18, and IL‐1α share related but distinct secretory routes. J Biol Chem 2019; 294:8325–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saeki A, Sugiyama M, Hasebe A, Suzuki T, Shibata K. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages by mycoplasmal lipoproteins and lipopeptides. Mol Oral Microbiol 2018; 33:300–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shibata K, Hasebe A, Into T, Yamada M, Watanabe T. The N‐terminal lipopeptide of a 44‐kDa membrane‐bound lipoprotein of Mycoplasma salivarium is responsible for the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 on the cell surface of normal human gingival fibroblasts. J Immunol 2000; 165:6538–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shibata K, Hasebe A, Sasaki T, Watanabe T. Mycoplasma salivarium induces interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐8 in human gingival fibroblasts. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1997; 19:275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fujii T, Tamura M, Tanaka S, Kato Y, Yamamoto H, Mizushina Y et al Gasdermin D (Gsdmd) is dispensable for mouse intestinal epithelium development. Genesis 2008; 46:418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. He WT, Wan H, Hu L, Chen P, Wang X, Huang Z et al Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin‐1β secretion. Cell Res 2015; 25:1285–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Y, Shi P, Chen Q, Huang Z, Zou D, Zhang J et al Mitochondrial ROS promote macrophage pyroptosis by inducing GSDMD oxidation. J Mol Cell Biol 2019; 11:1069–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rogers C, Fernandes‐Alnemri T, Mayes L, Alnemri D, Cingolani G, Alnemri ES. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase‐3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H et al Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase‐3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 2017; 547:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Into T, Nodasaka Y, Hasebe A, Okuzawa T, Nakamura J, Ohata N et al Mycoplasmal lipoproteins induce toll‐like receptor 2‐ and caspases‐mediated cell death in lymphocytes and monocytes. Microbiol Immunol 2002; 46:265–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Into T, Okada K, Inoue N, Yasuda M, Shibata K. Extracellular ATP regulates cell death of lymphocytes and monocytes induced by membrane‐bound lipoproteins of Mycoplasma fermentans and Mycoplasma salivarium . Microbiol Immunol 2002; 46:667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Into T, Kiura K, Yasuda M, Kataoka H, Inoue N, Hasebe A et al Stimulation of human Toll‐like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR6 with membrane lipoproteins of Mycoplasma fermentans induces apoptotic cell death after NF‐κB activation. Cell Microbiol 2004; 6:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]