Abstract

Objectives

As there is no objective test for pain, sufferers rely on language to communicate their pain experience. Pain description frequently takes the form of metaphor; however, there has been limited research in this area. This study thus sought to extend previous findings on metaphor use in specific pain subgroups to a larger, heterogeneous chronic pain sample, utilizing a systematic method of metaphor analysis.

Design

Conceptual metaphor theory was utilized to explore the metaphors used by those with chronic pain via qualitative methodology.

Methods

An anonymous online survey was conducted which asked for the descriptions and metaphors people use to describe their pain. Systematic metaphor analysis was used to classify and analyse the metaphors used into specific metaphor source domains.

Results

Participants who reported chronic pain completed the survey (N = 247, age 19–78, M = 43.69). Seven overarching metaphor source domains were found. These were coded as Causes of Physical Damage, Common Pain Experiences, Electricity, Insects, Rigidity, Bodily Misperception, and Death and Mortality.

Conclusions

Participants utilized a wide variety of metaphors to describe their pain. The most common descriptions couched chronic pain in terms of physical damage. A better understanding of pain metaphors may have implications for improved health care communication and provide targets for clinical interventions.

Keywords: chronic pain, metaphor, conceptual metaphor theory, taxonomy

Statement of contribution.

What is already known on this subject?

There is no objective test for the existence or nature of pain.

Chronic pain sufferers regularly use metaphor to describe their pain.

Metaphor use in chronic pain has not been comprehensively examined.

What does this study add?

A systematic analysis of pain metaphors in a heterogeneous chronic pain sample.

A taxonomy of pain metaphors, which has the potential to enhance communication in health settings.

Chronic pain, defined as pain persisting longer than 3 months, is associated with a range of psychological comorbidities including depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (Gormsen, Rosenberg, Bach, & Jensen, 2010; Manchikanti et al., 2006). However, there are no objective assessment measures for pain, meaning that people must rely on language or non‐verbal pain behaviours to communicate their suffering to others. These non‐verbal pain behaviours such as facial expressions or guarding are often involuntary and there is evidence to suggest that they are inaccurately decoded by others (Prkachin, Berzins, & Mercer, 1994). Consequently, there is a necessary reliance on verbal reporting of pain, which can be problematic due to difficulty in pain description (Munday, Kneebone, & Newton‐John, 2019).

One common use of language to communicate pain experience is metaphor (Aldrich & Eccleston, 2000; Kugelmann, 1999; Munday et al., 2019; Söderberg & Norberg, 1995). For example, ‘my pain is like barbed wire wrapped around my feet’. Metaphor elicitation is a way of accessing individual sense‐making around a particular experienced phenomenon, and metaphor analysis can facilitate the exploration of this individual sense‐making (Cassell & Bishop, 2019). It follows that metaphor may provide a powerful tool for chronic pain sufferers who lack objective means to verify and communicate their pain to family and health professionals.

Lakoff and Johnson (1980) provide a comprehensive definition of metaphor in their work on conceptual metaphor theory (CMT). They posit metaphors are not simply literary ‘decoration’, but rather a conceptual tool for thinking, organizing, and shaping reality. According to CMT, a conceptual metaphor consists of understanding one domain of experience (target domain) in terms of another (source domain). The target domain is typically more abstract and the source domain is typically more concrete. An example of a conceptual metaphor is ‘love is a journey’, where love is the target domain and journey the source domain. This conceptual metaphor can easily be seen in linguistic phrases such as ‘We’re at a crossroads’ or ‘They went their separate ways’. When seen in terms of journeys, we understand love as a path people move along, complete with obstacles. Other examples of conceptual metaphors are ‘anger is fire’ (e.g., ‘He was burning with rage’) and ‘argument is war’ (e.g., ‘He attacked my weak points’).

With the exception of the well‐known McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1975), there has been a dearth of research in the area of pain language. The MPQ, whilst providing an important perspective on the communication and assessment of pain, relies on single word adjectival descriptors and has been subject to numerous criticisms on this account (Bouhassira & Attal, 2009; Wilkie, Savedra, Holzemer, Tesler, & Paul, 1990). Some researchers have gone beyond single words to look at the use of metaphor in pain description. Semino (2010) posited neuropathic or chronic pain, given its abstractness and difficulty to explain in literal language, can be seen as a target domain. In contrast to this, nociceptive pain caused by physical damage, by virtue of being universal and familiar to people, is considered more concrete and easily understood, potentially making it a source domain through which chronic pain might be understood. Epidemiological studies have found that prevalence rates for chronic pain range from 19% to 30.7% in the Western world, meaning that a significant minority of the population will have an experience of chronic pain (Blyth et al., 2001; Breivik, Collett, Ventafridda, Cohen, & Gallacher, 2006; Johannes, Le, Zhou, Johnston, & Dworkin, 2010). However, it is worthy of note that everyone will have an episode of acute pain at some point in their lives. Semino (2010), looking at the 78 one‐word pain descriptors from the MPQ, as well as a sample of collocates of ‘pain’ in the British National Corpus of English, found that more than a third of these could be coded under the source domain ‘causes of physical damage’. Semino further broke this down into sub‐classes of damage causes, including by insertion of pointed objects (e.g., stinging), application of sharp objects (e.g., stabbing), pulling/tearing (e.g., wrenching), pressure/weight (e.g., crushing), a malevolent animate agent (e.g., torturing), high/low temperature (e.g., burning), and movement (e.g., shooting). Semino (2010) maintains the result of metaphorically describing chronic pain in terms of these more concrete causes of physical damage is the facilitation of an internal embodied simulation of pain experiences for the listener, which may provide the basis for an empathic response.

Hearn, Finlay, and Fine (2016) looked at metaphor use in a sample of 16 individuals with spinal cord injury and specific chronic neuropathic pain via semi‐structured qualitative interviews. Utilizing content analysis and interpretative phenomenological analysis, they found that metaphor use fell under three themes: pain as a personal attack, the desire to be understood (i.e., comparing pain to painful events which may have been experienced by the listener previously such as toothaches), and conveying distress without adequate terminology. Further to this, the study found that being female, younger, and being an outpatient were associated with increased metaphor use.

Bullo (2019) surveyed 131 women with endometriosis via online questionnaire, exploring how they conceptualized and articulated their pain. She found that in addition to feeling they did not have appropriate tools for pain description, the women tended to use elaborate metaphorical scenarios to convey their pain intensity. Using an adapted version of Semino's taxonomy, Bullo (2019) found that the metaphorical expressions could be grouped under three categories: pain as physical damage, pain as physical properties of elements, and pain as a transformative force, whereby sufferers perceive themselves as moving into a different location, state, or entity due to their pain. Bullo goes further to explore difficulties that arise when health professionals are faced with these metaphorical descriptions of pain, stating that a mismatch in assumptions or lack of a shared understanding can lead to miscommunication and thus potentially a delay in diagnosis. For example, metaphorical descriptions may undermine expected models of illness accounting and lead to minimization or dismissal or may lead to the pain being considered psychological in nature (Hodgkiss, 2000; Overend, 2014). Both these outcomes were reflected in Bullo's (2019) qualitative data. Here, metaphor as a tool to communicate may entail the risk of health professionals failing in their goal of providing the best medical care to patients in pain. It seems vital therefore to, as Bullo suggests, catalogue and understand the metaphors used by sufferers, in order to promote a shared code and understanding. This study sought to progress such an undertaking, by extending the previous limited diagnosis specific findings to a larger, heterogeneous chronic pain sample, utilizing a systematic method of metaphor analysis.

Methods

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant local ethics committee – University of Technology Sydney HREC REF: ETH18‐2192. Participants provided informed consent during the first part of the online survey, with the option of withdrawing from the study at any time during completion of the survey. If participants did not provide consent, they could not continue to the survey.

Protocol

Advertisements for the study were placed on websites and social media platforms of several Australian chronic pain organizations (e.g., Chronic Pain Australia) in order to recruit participants. These organizations were chosen through consulting with a pain clinician and because they are the peak consumer advocacy bodies for chronic pain sufferers in Australia. Pre‐requisites for participation were self‐reported diagnosis of chronic pain (defined as pain lasting longer than 12 weeks), being over 18 years of age, and English reading and writing ability. As an incentive, participants were eligible to enter a draw for one of five AUD$100 Gift Cards at completion of the survey. The information provided to the participants indicated the survey was voluntary and anonymous. The information section also detailed who the researchers were as well as the motivations for conducting this study. The survey was offered on the Qualtrics online platform and comprised of two parts: (1) basic demographics (sex, age, pain duration, education in years, self‐reported diagnosis, ethnicity, marital status, employment; see Tables 1 and 2), measures of pain outcomes such as intensity and interference via the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI; Cleeland & Ryan, 1994), and measures of mood via the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS‐21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). (2) A request, facilitated by a simple free text response box, for the descriptions and metaphors they use to talk about and describe their pain. The word metaphor was defined, several common examples were given, and participants were provided with basic prompts to use if they desired. Participants were encouraged to write as many different metaphors they have used in the time they have had chronic pain. The exact prompt is available in the Appendix. It is principally part two of the survey we report on here.

Table 1.

Sample demographics: age, pain duration, education (all in years)

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19 | 78 | 43.69 | 11.71 |

| Pain duration | 0.38 | 50 | 14.30 | 10.18 |

| Education | 9 | 25 | 14.71 | 3.11 |

Table 2.

Sample demographics: sex, diagnosis, ethnicity, marital status, employment status

| Variable | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 221 | 89.5 |

| Male | 26 | 10.5 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Endometriosis | 18 | 7.3 |

| Migraine | 20 | 8.1 |

| CRPS | 25 | 10.1 |

| Fibromyalgia | 71 | 28.7 |

| Ehlers–Danlos | 7 | 2.8 |

| Neuropathy | 27 | 10.9 |

| Arthritis | 69 | 27.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 230 | 93.1 |

| Asian | 3 | 1.2 |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | 1 | 0.4 |

| Other | 5 | 2 |

| Mixed | 8 | 3.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 118 | 47.8 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.8 |

| Divorced | 22 | 8.9 |

| Separated | 10 | 4 |

| Single | 44 | 17.8 |

| Long‐term relationship | 51 | 20.6 |

| Employment | ||

| Full Time | 37 | 15 |

| Part Time | 44 | 17.8 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 6.5 |

| Homemaker | 13 | 5.3 |

| Retired | 9 | 3.6 |

| Student | 12 | 4.9 |

| Not working due to pain | 95 | 38.5 |

| Other | 21 | 8.5 |

CRPS = Complex regional pain syndrome.

Participants

A total of 323 participants began and partially completed the survey, with 279 (86%) completing all parts. The exclusion criteria included those who selected ‘no’ to the question: ‘Have you been diagnosed with chronic pain by a health professional?’ (11 participants) and those with Pain Intensity scores below three on the Brief Pain Inventory (21 participants). After applying exclusion criteria, 247 participants remained. Tables 1 and 2 outline sample characteristics. The most common diagnoses are listed.

Analysis

Systematic metaphor analysis was utilized (Schmitt, 2005). This method involves the following steps. Firstly, a topic of analysis was chosen (chronic pain) and the authors (a PhD candidate and two experienced doctoral level clinicians/researchers) acquainted themselves with and assembled a ‘broad‐based collection of background metaphors’ relating to the target topic (p. 370). This was done via reading existing literature on common metaphor source domains, in particular those relating to pain, as well as research regarding chronic pain description (e.g., Bullo, 2019; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). With the aid of this collection of potential source domains, the next stage was inductive and involved identifying and coding the metaphors used in the data set. QSR International's NVivo (version 12, Melbourne, Australia) was utilized in order to code the metaphors into different source domains. The use of qualitative analysis software such as NVivo has been shown to be highly useful for systematic metaphor analysis (Kimmel, 2012). The target domain was not coded separately as it remained constant – participants’ chronic pain. Broad source domain coding was performed initially by the first author, resulting in 60 categories. Meetings were then held with all authors present in order to identify further source domains, refine and collate existing source domains, and reconstruct overarching metaphorical concepts from these. Agreement on final metaphor source domains and subdomains was reached through discussion until consensus was achieved. The final categories were then re‐examined by all parties in order to ensure they originated from and accurately represented the data. The categories of metaphors obtained were compared among themselves and previous research, in order to explore the differences and similarities. Finally, the coding of the first author (IM) was compared to that of an independent assessor, a Masters qualified registered psychologist and reliability calculated via Cohen's κ. Due to the large amount of data, a random sample of 10% of the data was utilized for this.

Results

Participants’ answers for the free text metaphor question ranged in length from three to 376 words. The number of distinct metaphor source domains used by each participant varied from zero to 13 (M = 5, SD = 3). Eleven per cent of the sample did not record any metaphors, instead, for example, writing about their experience of chronic pain more generally or about feelings of depression.

An independent‐samples t test was conducted to compare the number of metaphor source domains used for females and males. There was a significant difference in the number of source domains used in favour of females (M = 5.2, SD = 3) compared to males (M = 3.9, SD = 2.9); t(245) = 2.06, p = .041.

Outliers were defined as values three standard deviations above or below the mean. On this basis, four outliers were identified on the Education variable and these were consequently removed from the data set. Years of education was not significantly correlated with number of source domains used, r(239) = −.123, p = .056. Age was also not significantly correlated with number of source domains used, r(245) = −.036, p = .574.

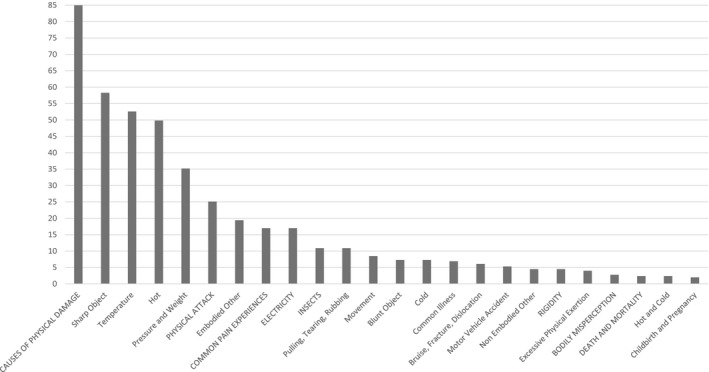

Using systematic metaphor analysis (Schmitt, 2005), seven overarching metaphorical concepts regarding chronic pain as the target domain were found. These and their subdomains are presented in Table 3. The percentage of the sample who used each source domain is presented in Figure 1. The overarching source domains were Causes of Physical Damage, Common Pain Experiences, Electricity, Insects, Rigidity, Bodily Misperception, and Death and Mortality.

Table 3.

Source domains for the target domain: chronic pain

| Source domains and subdomains | Example Metaphors |

|---|---|

| Causes of Physical Damage | |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | “… like I’ve been crushed by a car…” (P37); “Hit by a bus.” (P41) |

| Movement | “A jack hammer in my head.” (P158); “I can feel a heartbeat in my spine…” (P230) |

| Object – Sharp | “Barbed wire wrapped around my feet.” (P13); “A million hot needles all over my body.” (P30) |

| Object – Blunt | “…like I'm being hit with a sledge hammer every minute of the day.” (P263) |

| Physical Attack | |

| Embodied Other | “Somebody driving a knife into my bones and muscles and twisting it.” (P47) |

| Non‐embodied Other | “Like I have been punched in my face.” (P127) |

| Pressure/Weight | “… like a mix of substance like mercury and sticky molasses have been injected into parts of my body and set like concrete.” (P27) |

| Pulling/tearing/rubbing | “It feels like my muscles are getting tied up in knots and being pulled tight from each end.” (P125) |

| Temperature | |

| Hot | “It feels like I'm burning but I can't put the fire out. It feels like embers are smouldering inside.” (P107) |

| Cold | “Ice running through body.” (P81); “Headache like a freezing head.” (P216) |

| Hot‐Cold | “A deep frozen burning inside.” (P62); “The pain feels like burning and cold to the point of torture.” (P113) |

| Common Pain Experiences | |

| Bruise‐fracture‐dislocation | “Constantly having a sprained ankle throughout my whole body.” (P202) |

| Childbirth & Pregnancy | “Baby kicking me in the ribs/belly.” (P20) |

| Common Illness | “Like a giant toothache all over.” (P88); “The pain feels like a constant migraine throughout my body…” (P263) |

| Excessive Physical Exertion | “It feels like I have run 15 km at the gym.” (P196); “…like I have ran a long distance but haven't.” (P206) |

| Electricity | “The pain feels like I am holding a live wire and electricity is burning through my body.” (P24) |

| Insects | “It feels like a horse kicks me in the butt every morning and left millions of ants running inside my leg.” (P169) |

| Rigidity | “My joints make my legs feel like stiff tree trunks.” (P103) |

| Bodily Misperception | “My foot does not belong to me.” (P113); “…(worst days) feels as if my leg is not part of me.” (P156) |

| Death and Mortality | “Feels like rigamortus [sic] first thing every morning” (P147); “My whole body aches like hell in all my bones.” (P43) |

Figure 1.

Percentage of sample who used each source domain. The overarching source domains are displayed in capital letters.

There was good agreement between the two independent coders, κ = .831 (95% CI, 0.76–0.90), p < .0005.

Mixed metaphors

It is important to note that participants often utilized several metaphor source domains in a single phrase. For example, the phrase ‘the pain feels like a scorching hot fire poker is being shoved up my feet every second’ (P14) contains both the Temperature–Heat source domain, as well as the Causes of Physical Damage via Sharp Objects one. In this study, metaphor source domains were not treated as discrete or exclusive categories and thus in such instances both source domains were coded.

Causes of physical damage

This was the largest category and accounted for the majority of metaphor source domains used by participants. However, within this broad category were distinct subcategories, outlined below, with each highlighting different methods of causing physical damage to the pain sufferer. Several of these source domains are consistent with Semino's (2010) classification, such as physical damage via movement, or via temperature.

Causes of physical damage via motor vehicle accident

Participants frequently compared their pain to having been ‘hit’ by either a bus, truck, or car. One participant went further, saying that their pain felt like having ‘been crushed by a car’, whilst another described it as ‘like I’ve been run over, reversed over and run over again’ (P37, P241).

Causes of physical damage via movement

This source domain contains words and descriptions to do with movement, which would cause damage if it occurred within the body (Semino, 2010). This includes descriptions of pain as ‘shooting’ or ‘throbbing’ as well as a ‘heaving pain in my legs’ (P99). Participants also described their pain as a ‘heartbeat’, which ‘pulses kinda’ (P279).

Causes of physical damage via object (sharp/blunt)

Substantial numbers of participants described their pain in terms of damage via an object, with more participants referencing a sharp, rather than blunt object. A large variety of sharp instruments were used in pain descriptions, including knives machetes, screwdrivers, pokers, knitting needles, cheese graters, hand drills, metal spikes, razors, pins, and shards of glass. At one end of this source domain, participants simply described their pain as ‘stabbing’, whilst the other end featured elaborate metaphors such as their pain feeling ‘like I have two large stakes being plunged through both my temples and through the bottom of my skull’ or ‘like broken glass rubbing across your stomach’ (P168, P42).

In terms of blunt objects, instruments such as bricks, sledgehammers, cricket bats, hammers, and rulers were referenced. For example, pain was described as being ‘just hit repeatedly in the temple with a large rubber mallet’ or ‘like I’ve been smacked in the back with a baseball bat…’ (P3, P154).

Causes of physical damage via physical attack (embodied and non‐embodied malevolent other)

Many participants described their pain in terms of a physical attack. Of the descriptions without an explicit embodied attacker, pain was described as akin to being in a physical fight, to having been ‘punched’ or ‘kicked’. However, the vast majority of these descriptions featured an embodied attacker, a malevolent agent that harmed them. This source domain was often mixed with others, as the embodied attacker utilized a wide variety of methods to harm the participant. Examples include descriptions of their pain feeling like ‘something with claws is grasping and twisting my leg as tight as it can’ or like ‘someone poured gas on me and lit me on fire’ (P5, P74). At times, the attacker was more defined than a ‘something’ or ‘someone’, instead becoming a ‘giant crushing my bones’, a ‘large snake’, or a ‘monster in my head’ (P76, P37, P139).

Causes of physical damage via pressure and weight

Physical damage as a result of pressure or weight was also a common source domain. Single word metaphorical descriptors included pain that was ‘pinching’, ‘pressing’, ‘crushing’ ‘tight’, or ‘heavy’. Multiple participants described their pain as feeling like their body part in pain was in a ‘vice’, with pressure being exerted on it. More elaborate and unusual pressure metaphors included comparing the feeling to like ‘being constricted by a large snake, my breath being squeezed out of me’ (P37). In terms of weight, participants described their pain as something heavy, likening it to ‘an anchor on my chest’ or ‘like wearing the lead vests they put on you for an X‐ray…’ (P18, P3). Others compared their limbs to ‘cement blocks’ or like an elephant sitting on their body (P116, P241).

Causes of physical damage via pulling/tearing/rubbing

Metaphors utilizing this source domain featured single word descriptors such as ‘tearing’, ‘pulling’, ‘wrenching’, ‘drawing’, and ‘squeezing’ pain. Pain was described as a ‘violent tearing sensation at various intervals’ or ‘like there are excessively taut ropes between my neck and my toes, running down my spine, through my buttocks and the back of my legs’ (P190, P256). Others experienced a ‘grinding’ pain or felt as if ‘sandpaper is being rubbed over my skin’ (P62).

Causes of physical damage via temperature (hot, cold, hot–cold)

The source domain of temperature was harnessed by over half of the sample, with metaphors of heat being most prevalent, followed by cold, as well as a small subsample of participants who described their pain as both hot and cold in the same phrase.

Metaphorical descriptions of their pain as ‘burning’ or of a body part ‘on fire’ were common. More elaborate metaphors included pain as a ‘hot curling iron sitting on my skin’ or ‘like my joints are constantly being injected with boiling hot glue’ (P172, P263). One participant painted a vivid picture of ‘a heavy burning weight of lava inside my shoulder, sitting on the scapula dripping down and wrapping around my ribcage, precariously balanced such that any excess activity upsets the balance and sends it pouring down my arm and leg and exploding up into my skull’ (P226). Use of both the heat and sharp objects source domain was also common, with descriptors of a ‘red hot dagger’, ‘stabbed with a hot poker’ and ‘hot knife’ (P100, P93, P254).

Participants also used the other end of the temperature spectrum, describing their pain as ‘having my foot constantly in a bucket of ice’ or feeling ‘as though my bones are blocks of ice’ (P156, P4). Pain was described as ‘freezing’ and like ‘being stabbed with an icepick’ (P173).

In addition to the above, a small number of participants described their pain as both cold and hot, simultaneously. For example, one participant wrote ‘pain feels icy cold and burning all at once’, whilst another described it as a ‘deep frozen burning’ (P189, P62).

Common pain experiences

Participants drew from common experiences of pain in ordinary life in order to explain their chronic pain. They used examples such as injuries, illnesses, pregnancy, and physical exertion. However, they often either extended the extent of these pain experiences or utilized them in non‐literal or novel ways.

Bruise–fracture–dislocation

Chronic pain was described as feeling like ‘one big bruise’ or having ‘put joints out of place’ (P143, P87). Participants used metaphors of broken bones to illustrate the pain they were in, despite not having these injuries literally. For example, one participant described their feet aching ‘like someone has broken my toes’, whilst another wrote their pain felt like ‘walking with broken bones in my feet’ (P279, P103).

Childbirth/pregnancy

A few participants compared pain to aspects of pregnancy and childbirth, comparing the pain they felt as ‘similar to those I experience during labour’ (P133). Others compared their pain to ‘full blown labour with no pain relief’, ‘contractions’ or like a ‘baby kicking me in the ribs/belly’ (P188, P84, P20).

Common illness

Participants drew upon common illnesses such as the flu or a headache; however, they extended these illnesses to perpetuity: for example ‘having the flu 24/7 for years’ or ‘a mongrel headache that never goes away’ (P274, P28). They also utilized common pain experiences such as toothaches, but in novel ways, positioning this toothache where they felt their pain. For example, one participant described a ‘toothache in my hip’ whilst another had a ‘toothache in my right knee’ and yet another implored the reader to ‘imagine a toothache in your shoulder’ (P71, P252, P230).

Excessive physical exertion

Another common pain experience which participants drew upon was that of excessive physical exertion, such as ‘working 24/7’ or feeling like ‘I’ve done an intensive workout at the gym, but I actually haven’t’ (P20, P173). Their pain was also compared to having ‘been in a marathon’ (P197). Their pain felt as if they had expended tremendous energy and work, when in fact they had not.

Electricity

This source domain covered multiple types of electricity such as lower grade electricity (e.g., buzzing, humming, tingling) right through to an electric paroxysm (lightning bolts, electric shocks, electrocution). References to lightning were common, for example ‘feels like lightning is shooting across my ribs or through my limb’ and a ‘lightning strike pain’ (P103, P145). Participants also spoke of their pain as ‘electricity running through my veins’ and as a ‘…buzzing/humming under my skin that makes me flinch and twitch’ (P121, P24).

Insects

Participants compared their pain to a feeling of insects on top of their skin: ‘I can feel bugs crawling all over me’ and ‘…I am being walked over by insects 24/7 × 365 like caterpillars, biting ants, horseflies, spiders, cockroaches, stung by scorpions and mosquitoes and sandflies and midgies’ (P103, P4). At times, the particular insect was defined, for example ants or bees, and at other times simply referred to as ‘bugs’ or ‘something’. Participants also wrote of feeling like there were insects under their skin, for example ‘ants crawling under the skin’ or ‘a million bee's in my shoulders’ (P52, P248).

Rigidity

Participants compared their pain to ideas of stiffness and immobility, with their pain rendering them ‘as stiff as the tin man’ or ‘like my muscles have turned into painful rocks’ (P176, P30). One participant felt as if they had ‘a tight piece of string going from my head down to my hand’ (P63). Parts of their body ‘locked up’ or ‘jammed stuck’ and were unable to function fluidly as normal.

Bodily misperception

This was another small, but distinct source domain. Participants described feeling like their limb or place of pain was not a part of them, for example remarking ‘my foot does not belong to me’ or ‘like the original place of pain is not a part of me, sometimes my hand that is all deformed now is slimy’ (P113, P84). The latter part of this quote displays a marked type of revulsion as well as a changed perception of their limb, also echoed in another participant feeling like their hand ‘…is swollen 10 times than actually it [is]’ (P248). Lastly, a lack of control over their own body in pain is displayed here: ‘the pain feels like my brain does not control my body’ (P25).

Death and mortality

Although small, this source domain nonetheless emerged as distinct and unable to be subsumed under another category. Included among it are references to the process of dying, such as ‘I often feel like my insides are being cut off from blood circulation and I can feel pieces of myself die’ (P187). A premonition or longing for death due to pain is also present: ‘The pain in my head makes me feel like I am going to die, or that I want to die’ (P198). More covert allusions to death exist in references to rigour mortis, hell, and rotting.

Discussion

This study begins the work of establishing a taxonomy of the types of metaphors sufferers of chronic pain use. Drawing on CMT, we found that participants in our sample utilized a wide variety of metaphor source domains to elucidate the target domain of chronic pain. However, seven source domains in particular were found: Causes of Physical Damage, Common Pain Experiences, Electricity, Insects, Rigidity, Bodily Misperception, and Death and Mortality.

The study found that women generated significantly more metaphors than men, thus using a larger number of source domains. This is in line with previous research, such as Strong et al. (2009) who found that when asked to write about a past pain event, women used more words overall, more MPQ descriptors, and more graphic language than men. Hearn et al. (2016) also found a significant gender difference, with women using more metaphors than men. However, contrary to Hearn et al. (2016)'s findings, age was not a significant predictor of metaphor use.

The most common overarching source domain utilized was Causes of Physical Damage. This study found evidence that people, when asked for their pain metaphors, do in fact utilize all the subcategories which Semino (2010) proposed in her taxonomy and which Bullo (2019) also found reflected in her data, for example Physical Damage via Sharp Object, Pressure/Weight, Temperature, Pulling/Tearing, and Movement. However, in our study, further subcategories emerged from the data, which included the addition of Physical Damage via Blunt Instrument (as opposed to only sharp), as well as by Motor Vehicle Accident, and the extension of some of the categories. From this study, it appears that people use a wider variety of metaphorical language than that contained in the MPQ to describe their pain in terms of physical damage.

Included among the categories of physical damage is one source domain which stands out, in part because it is not an exclusive or distinct category, but rather overlaps with many of the other physical damage source domains. This is the Physical Attack category, most commonly perpetuated by a malevolent embodied agent, whom inflicts damage via sharp or blunt instruments, temperature, or force. This is consistent with previous research into pain metaphors (Bullo, 2019; Munday et al., 2019). It is also consistent with the findings of Lascaratou (2007), who in a corpus‐based study of nearly 70,000 words from 131 conversations recorded between doctors and patients found that participants spoke of their pain as ‘…a highly distinguishable undesirable possessed entity and as an external to the self moving force capable of invading the individual as an uninvited intruder, ultimately acting as a malevolent aggressor, a torturer, and an imprisoning enemy’ (p. 140). By personifying their pain as an enemy, sufferers may create a target to fight against, as well as create a separation from a healthy pain‐free self. This linguistic separation from pain may provide hope and promote a more positive self‐view; however, it may also negatively impact acceptance and adjustment to pain as well as potential rehabilitation (Osborn & Smith, 2006).

The category of Bodily Misperception adds more depth to this tendency of separating themselves from the pain. Here, participants explicitly describe feeling as if their painful body part is not a part of them or being unable to control their own body. However, another way this category can be viewed is as a primary feature of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Research shows that CRPS patients, in addition to having distorted body representation, often report feeling as if their affected limb does not belong to them, seeing it as strange and viewing it with hostility (Halicka, Vittersø, Proulx, & Bultitude, 2020; Lewis, Kersten, McCabe, McPherson, & Blake, 2007). This is exemplified by one participant who described it as ‘like the original place of pain is not a part of me, sometimes my hand that is all deformed now is slimy’ (P84). Research has shown that although chronic limb pain of other origin patients also use these types of descriptions, it is significantly more common in CRPS populations (Frettlöh, Hüppe, & Maier, 2006). Here, we see that the metaphors people use may provide diagnostic clues.

Participants used a much wider variety of pain metaphors than those of physical damage however. For example, another way of enhancing understanding may be through comparing chronic pain to a painful event that the listener may have already experienced. This is epitomized in the source domain Common Pain Experiences. In these metaphors, participants used concrete painful events such as toothaches and broken bones to describe their more abstract chronic pain. Often, participants took a pain experience such as a toothache and transferred it to their body part in pain, describing for example a toothache in their back or knee. This reflects previous research which has shown that people in pain reliably refer to common pain experiences in order to facilitate understanding in their listener (Hearn et al., 2016; Munday et al., 2019). The desire to be understood was evident throughout the data.

Also evident from the data is the prevalence of certain metaphors, which may be indicative of linguistic conventionalization. Language‐based tools such as the MPQ, whilst initially generated from patient language, may nonetheless have a shaping effect on pain vocabulary. For example, the use of ‘stabbing’ to describe pain was extremely frequent, with 92 instances of the word ‘stab’ (including stabbing, stabbed, stabs) found in the data set. Other examples included descriptions of ‘electric shocks’ or like being in a ‘vice’. Such descriptions may be examples of dead metaphors – metaphorical expressions that, through common usage, have lost metaphoric force. This loss of force/effectiveness, is explored in depth by Semino (2010). She suggests that different types of metaphorical pain descriptions may vary in terms of their potential to elicit an embodied simulation response. Through looking at linguistic data and research, a metaphor’s level of detail, degree of creativity, and textual complexity may affect the listener’s response – its nature and intensity (Semino, 2010). That is, not all metaphors will have the same effect.

In CMT, source domains are typically concrete, in order to facilitate understanding of the more abstract target domain. It is noteworthy therefore, that of the source domains found above, there was one which could be considered more abstract in nature – Death and Mortality. Whilst death is a certainty, it is not something knowable. Kövecses (2016) remarks that the use of an abstract source domain may occur, but that when it does, there is ‘always some special poetic, stylistic, aesthetic, and so on, purpose or effect involved’ (p. 16). However, as our participants were not writing for literary or art making purposes, there may be another answer, outside of stylistic reasons, as to why they sought to communicate their pain via the abstract. It may be that their pain intensity was so great; they could only attempt to communicate it through death itself.

Interestingly, a small proportion of the sample (11%) did not write any metaphors at all, despite metaphor having been defined, asked for explicitly, and with exemplar prompts. Some appeared to have misunderstood the question, writing more generally on their experience of pain, such as being disbelieved by health professionals. However, it seems likely that, following on from the literature which states that people find it difficult to communicate pain (Bullo, 2019), some people may simply lack this particular tool of communication and find it too difficult to describe their pain in such a way. Metaphor may be a valuable resource, but perhaps not everybody has it available, leaving some to rely on other means of communication.

Implications

Metaphor is both an inescapable and important aspect of language and thought, which can be an important tool for understanding and dealing with pain (Bullo, 2019; Demjén & Semino, 2016; Loftus, 2011). A deeper understanding of the metaphors that people living with chronic pain utilize is thus an important area of research. This study utilized systematic metaphor analysis to uncover the most commonly used chronic pain metaphors. It is unique in that it is, to our knowledge, the largest sample studied, as well as being diagnostically heterogenous, in order to access the full diversity of metaphors as the language of chronic pain. Previous research has used relatively small samples and focused only on specific subgroups of chronic pain. As a consequence, this study has gathered the broadest range of pain metaphors to date, exceeding the breadth of both previous studies and existing instruments such as the MPQ. This illustrates that if you rely on small qualitative studies or restrict diagnosis type, results may be narrow and not fully representative.

A better understanding of the language used by those in pain may have implications for communication in health care settings. Health professionals may be less prone to dismiss, minimize, or misunderstand a patient's pain when expressed through metaphor, if they are more aware and knowledgeable about it. Further, understanding pain metaphors may have useful clinical applications. Metaphor, more broadly, has long been harnessed in psychological therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011) in order to facilitate patient understanding and effect change. However, health care research is now also starting to utilize metaphor as a tool. For example, Gallagher, McAuley, and Moseley (2013) developed a book of metaphors explaining key biological concepts for chronic pain. Participants given this book were significantly more likely to read it, increased their knowledge of pain biology significantly more and decreased their catastrophic thoughts significantly more, than participants given a standard advice booklet. Semino (2014) has also developed a ‘metaphor menu’ for cancer patients to support pain communication in that population. The current research may support the development of assessment tools which go beyond the single word adjectival paradigm of the MPQ and instead provide a richer base of metaphors from which chronic pain patients can select. In addition to this, identifying and targeting patient's specific metaphors may ultimately create a new focus as well as a tool, for work in therapy. For example, identifying and modifying maladaptive or unhelpful pain metaphors with the aim to either transform them or decrease their use, similarly to how pain management programs currently try to reduce catastrophic thinking (Wideman & Sullivan, 2011).

Limitations

As participants were recruited online they necessarily self‐selected as having chronic pain, rather than being drawn from, for example a cohort hospital sample. This leaves the possibility of bias sampling and may therefore impact the generalizability of our findings to the full population of chronic pain sufferers.

Other cautions to generalization apply. Although our participants were of a wide variety of ages, with pain stemming from a variety of diagnoses, the sample was 89.5% female, well educated, and 93.1% white. This necessarily means that their results may not be representative of a more varied sample in these regards. Additionally, as languages differ significantly from each other, these results will likely only be applicable to English speakers.

Lastly, we acknowledge the potential biasing factor of the prompts and example metaphors chosen to elicit participant metaphors. Participants may have been more likely to generate metaphors which held some relation to these prompts.

Future directions

This study looked at what source domains those with chronic pain in general used. Future research may aim to delve more deeply into this by looking at whether people with different pain diagnoses use the same or different metaphors to each other. If there are significant differences, or specific metaphor profiles of diagnostic groups, this may potentially inform assessment. In addition to this, future research may look at how aspects of the pain experience such as pain intensity, pain related disability, and mood affect the types of metaphors used. Another interesting area to explore would be the creativeness of more elaborate metaphors and what purpose that serves. Lastly, future research might look into healthy populations who have only had acute pain, in order to see what pain metaphors, if any, they use and thus determine whether those used by chronic pain sufferers are intrinsic to pain in general or are shaped by chronicity.

Author contributions

Imogene Munday (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing); Toby Newton‐John (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing); Ian Kneebone (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Prompt given to elicit metaphors

Many people use metaphors in order to describe their pain. Metaphors are figures of speech that describe something in a way that isn’t literally true, but helps explain an idea or make a comparison.

These can be statements such as;

“It feels like ants in my body.”

“It feels like a knife slicing into me.”

“It feels like something that is burning inside you.”

“It feels like I carry a very heavy load.”

How would you describe your pain and what it feels like? What metaphors or descriptions do you use to talk about your pain?

Please feel free to write as many different metaphors or descriptions as you have used over the time you have had chronic pain. You may use the prompts below if you like to help you get started.

Living with pain is like…

The pain feels like…

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Aldrich, S. , & Eccleston, C. (2000). Making sense of everyday pain. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 1631–1641. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00391-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, F. M. , March, L. M. , Brnabic, A. J. , Jorm, L. R. , Williamson, M. , & Cousins, M. J. (2001). Chronic pain in Australia: A prevalence study. Pain, 89, 127–134. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00355-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira, D. , & Attal, N. (2009). All in one: Is it possible to assess all dimensions of any pain with a simple questionnaire? Pain, 144(1), 7–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivik, H. , Collett, B. , Ventafridda, V. , Cohen, R. , & Gallacher, D. (2006). Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. European Journal of Pain, 10, 287–287. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullo S. (2019). “I feel like I’m being stabbed by a thousand tiny men”: The challenges of communicating endometriosis pain. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1363459318817943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C. , & Bishop, V. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: Exploring themes, metaphors and stories. European Management Review, 16(1), 195–207. 10.1111/emre.12176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland, C. S. , & Ryan, K. M. (1994). Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23(2), 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demjén, Z. , & Semino, E. (2016). Using metaphor in healthcare In Demjén Z. & Semino E. (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 385–399). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frettlöh, J. , Hüppe, M. , & Maier, C. (2006). Severity and specificity of neglect‐like symptoms in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) compared to chronic limb pain of other origins. Pain, 124(1–2), 184–189. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, L. , McAuley, J. , & Moseley, G. L. (2013). A randomized‐controlled trial of using a book of metaphors to reconceptualize pain and decrease catastrophizing in people with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(1), 20–25. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182465cf7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormsen, L. , Rosenberg, R. , Bach, F. W. , & Jensen, T. S. (2010). Depression, anxiety, health‐related quality of life and pain in patients with chronic fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. European Journal of Pain, 14, 127.e1–127.e8. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halicka, M. , Vittersø, A. D. , Proulx, M. J. , & Bultitude, J. H. (2020). Neuropsychological changes in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Behavioural Neurology, 2020, 1–30. 10.1155/2020/4561831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S. C. , Strosahl, K. D. , & Wilson, K. G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, J. H. , Finlay, K. A. , & Fine, P. A. (2016). The devil in the corner: A mixed‐methods study of metaphor use by those with spinal cord injury‐specific neuropathic pain. British Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 973–988. 10.1111/bjhp.12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkiss, A. (2000). From lesion to metaphor: Chronic pain in British, French and German medical writings, 1800–1914. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, C. B. , Le, T. K. , Zhou, X. , Johnston, J. A. , & Dworkin, R. H. (2010). The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: Results of an Internet‐based survey. The Journal of Pain, 11, 1230–1239. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M. (2012). Optimizing the analysis of metaphor in discourse: How to make the most of qualitative software and find a good research design. Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 10(1), 1–48. 10.1075/rcl.10.1.01kim [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Z. (2016). Conceptual metaphor theory In Demjén Z. & Semino E. (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 31–45). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kugelmann, R. (1999). Complaining about chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine, 49, 1663–1676. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. , & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Lascaratou, C. (2007). The language of pain. Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. S. , Kersten, P. , McCabe, C. S. , McPherson, K. M. , & Blake, D. R. (2007). Body perception disturbance: A contribution to pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). PAIN®, 133(1–3), 111–119. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus, S. (2011). Pain and its metaphors: A dialogical approach. Journal of Medical Humanities, 32, 213–230. 10.1007/s10912-011-9139-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, P. F. , & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti, L. , Cash, K. A. , Damron, K. S. , Manchukonda, R. , Pampati, V. , & McManus, C. D. (2006). Controlled substance abuse and illicit drug use in chronic pain patients: An evaluation of multiple variables. Pain Physician, 9, 215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack, R. (1975). The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain, 1, 277–299. 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday I., Kneebone I., & Newton‐John T. (2019). The language of chronic pain. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–8. Advance online publication. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1624842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, M. , & Smith, J. A. (2006). Living with a body separate from the self. The experience of the body in chronic benign low back pain: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 20, 216–222. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overend, A. (2014). Haunting and the ghostly matters of undefined illness. Social Theory & Health, 12(1), 63–83. 10.1057/sth.2013.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prkachin, K. M. , Berzins, S. , & Mercer, S. R. (1994). Encoding and decoding of pain expressions: A judgement study. Pain, 58, 253–259. 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90206-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, R. (2005). Systematic metaphor analysis as a method of qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 10, 358–394. [Google Scholar]

- Semino, E. (2010). Descriptions of pain, metaphor, and embodied simulation. Metaphor and Symbol, 25, 205–226. 10.1080/10926488.2010.510926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semino, E. (2014). A ‘metaphor menu’ for cancer patients. Retrieved from https://ehospice.com/uk_posts/a‐metaphor‐menu‐for‐cancer‐patients/ [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg, S. , & Norberg, A. (1995). Metaphorical pain language among fibromyalgia patients. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 9(1), 55–59. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1995.tb00266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong, J. , Mathews, T. , Sussex, R. , New, F. , Hoey, S. , & Mitchell, G. (2009). Pain language and gender differences when describing a past pain event. PAIN®, 145(1–2), 86–95. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideman, T. H. , & Sullivan, M. J. (2011). Reducing catastrophic thinking associated with pain. Pain Management, 1, 249–256. 10.2217/pmt.11.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, D. J. , Savedra, M. C. , Holzemer, W. L. , Tesler, M. D. , & Paul, S. M. (1990). Use of the McGill Pain Questionnaire to measure pain: A meta‐analysis. Nursing Research Nursing Research, 39(1), 36–41. 10.1097/00006199-199001000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.