Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic that attracted global attention in December 2019 is well known for its clinical picture that is consistent with respiratory symptoms. Currently, the available medical literature describing the neurological complications of COVID-19 is gradually emerging. We hereby describe a case of a 31-year-old COVID-19-positive patient who was admitted on emergency basis. His clinical presentation was primarily neurological, rather than the COVID-19’s classical respiratory manifestations. He presented with acute behavioural changes, severe confusion and drowsiness. The cerebrospinal fluid analysis was consistent with COVID-19 encephalitis, as well as the brain imaging. This experience confirms that neurological manifestations might be expected in COVID-19 infections, despite the absence of significant respiratory symptoms. Whenever certain red flags are raised, physicians who are involved in the management of COVID-19 should promptly consider the possibility of encephalitis. Early recognition of COVID-19 encephalitis and timely management may lead to a better outcome.

Keywords: medical management, infection (neurology), neuroimaging, infectious diseases, global health

Background

The COVID-19 virus, classified as SARS‐CoV-2, emerged in Wuhan, China, and was initially identified as the new coronavirus disease. The WHO eventually named it as COVID-19 on 11 February 2020. Later on 5 June 2020, the WHO officially announced that COVID-19 has infected 6 535 354 individuals and claimed more than 387 155 lives worldwide.1 COVID-19 is not the first coronavirus to infect humans. Other human coronaviruses (HCoV) include six other members designated as SARS‐CoV, middle east respiratory syndrome‐CoV, HCoV‐HKU1, HCoV‐NL63, HCoV‐OC43 and HCoV‐229E.2

As described in the literature, COVID-19 possesses neuroinvasive potentials, which makes the central nervous system (CNS) an important target. There are multiple proposed mechanisms of CNS involvement, including retrograde movement from the olfactory nerve, entry into CNS via circulating lymphocytes or entry via permeable blood–brain barrier.3

There are several neurological manifestations that have been described in patients with severe respiratory distress.4 But this case is unique due to the fact that the patient’s symptoms were mainly neurological in nature, that was preceded with a mild, self-limiting cough. What also enhances the uniqueness of this case is the presence of a very few reported cases of established encephalitis alongside an objective evidence of the virus itself in CNS.5 6

Case presentation

On 10 May 2020, a 31-year-old previously healthy man, who happened to live in a particular area with uncontrolled COVID-19 spread in Dubai, started experiencing some mild, self-limiting cough symptoms without any episode of fever. This was not brought to medical attention and resolved spontaneously within 2 days. On 12 May 2020, he started to become physically and verbally aggressive, as stated by his acquaintances. On 14 May 2020, he presented to the emergency department in Rashid Hospital with an altered mental state and abnormal behaviour. The patient’s acquaintances clearly stated that the patient does not suffer from any comorbidities and denied any history of alcohol intake or substance abuse.

The patient was afebrile. His heart rate was 76/min, blood pressure was 120/80 mm Hg, respiratory rate was 12/min and oxygen saturation on room air was 100%. Neurological examination revealed acute confusion state associated with severe agitation and fluctuations in the level of consciousness. Cranial nerves examination was unremarkable. The motor examination including tone, power in upper and lower limbs, and deep tendon reflexes was normal as well. Coordination was difficult to assess at this point. No neck stiffness or other meningeal signs were evident.

Chest examination, including inspection, auscultation, percussion and palpation, revealed no abnormalities. Abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen and present bowel sounds, without any evidence of tenderness or organomegaly.

Investigations

Imaging

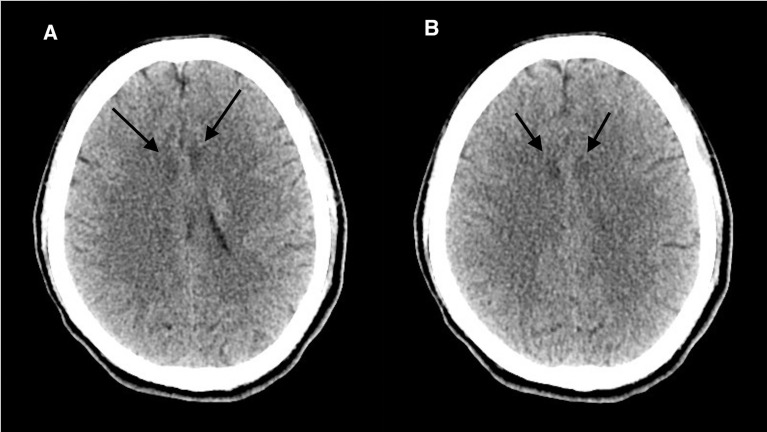

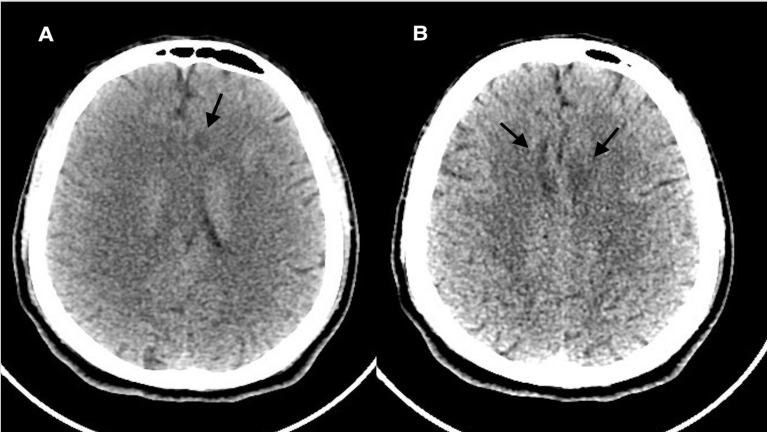

Brain CT without contrast revealed multiple hypodensities in the external capsules bilaterally, the insular cortex and the deep periventricular white matter of the frontal lobes bilaterally (figure 1). Another brain CT was performed 48 hours after the initial one, but did not reveal any significant interval changes (figure 2).

Chest X-ray was unremarkable.

Pulmonary CT showed normal attenuation in both lungs without any appreciable air space consolidations, pneumothorax or pleural effusion. No evidence of ground glass opacities.

Pulmonary CT angiogram shows good flow of contrast of the main pulmonary trunk, right and left main pulmonary arteries, as well as the lobar, segmental and subsegmental branches without any appreciable filling defects. No evidence of pulmonary embolism.

Abdominal CT was normal

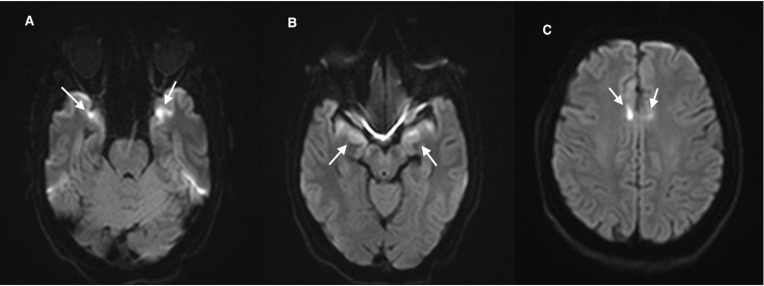

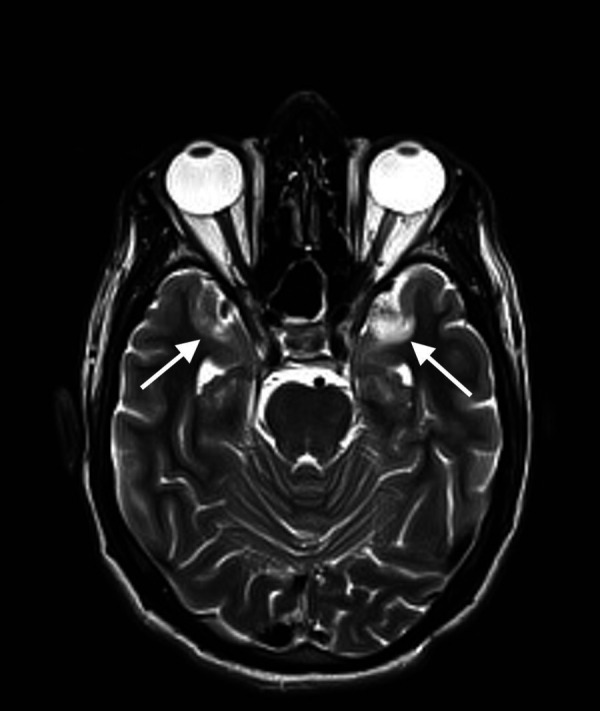

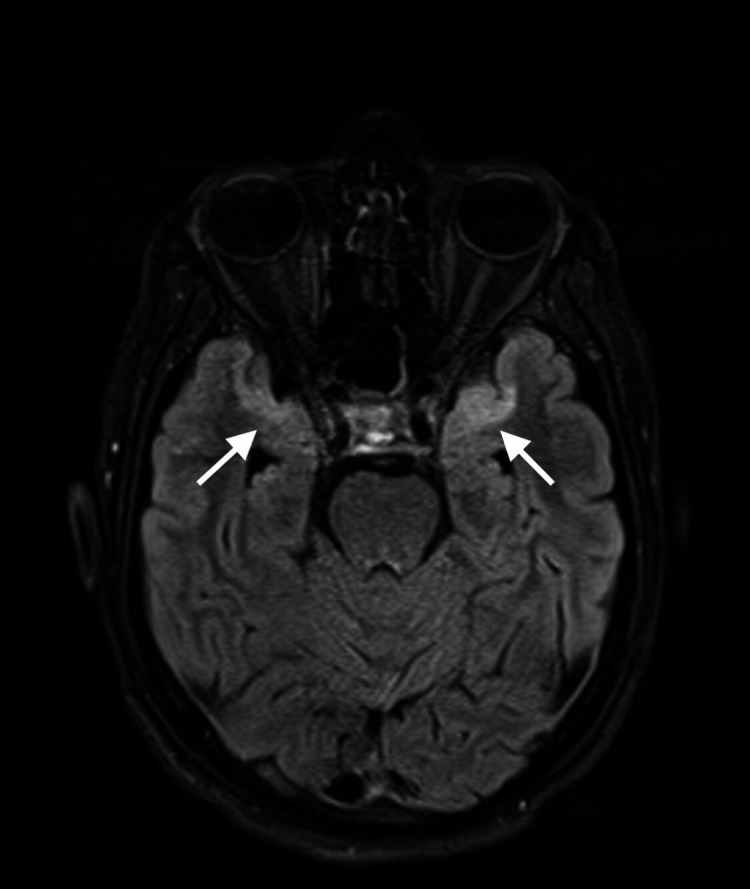

Brain MRI with contrast, performed after 2 weeks to comply with our hospital’s protocol that only allows COVID-19-negative patient to get in contact with the MRI machine, revealed abnormal signal intensity in the temporal lobe cortex bilaterally in a rather symmetrical fashion. In addition, the involvement of the parasagittal frontal lobes bilaterally was evident as well, displaying bright signals on T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery and T2-weighted images with corresponding diffusion restriction. These findings are suggestive of encephalitis (figures 3–5).

Figure 1.

(A, B) Initial CT of the brain without contrast axial image revealing bilateral symmetrical hypodensities in the bifrontal lobes.

Figure 2.

(A, B) Repeated CT of the brain without contrast axial image after 24 hours still revealing hypodensities in the bifrontal lobes.

Figure 3.

(A, B) MRI of the brain diffusion-weighted images axial image revealing rather symmetrical diffusion restriction in the anteromedial temporal lobes bilaterally, and (C) areas of diffusion restriction in the parasagittal frontal lobes bilaterally.

Figure 4.

MRI of the brain T2-weighted axial image revealing hyperintense signals in the temporal lobe cortex bilaterally.

Figure 5.

MRI of the brain T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery axial image revealing hyperintense, rather symmetrical, signals in the anteromedial temporal lobes bilaterally.

Electrophysiological studies

Electroencephalogram did not display any significant epileptic discharges. That could possibly be due to the masking effect of lorazepam that was given to the patient to manage his agitation.

Differential diagnosis

Living in an area where there is a higher infection rate of COVID-19 is a red flag by itself. Given the presenting symptoms, COVID-19 encephalitis should be considered, as well as acute metabolic disorders, such as renal and hepatic encephalopathies. Our patient had an initially elevated bilirubin level; however, the alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyl transferase were within normal limits (table 1). Hepatitis C antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen were negative, and abdominal CT scan was normal too. The elevated bilirubin normalised within 2 weeks, indicating that this elevation was non-specific. Acute cerebrovascular accident or toxic insults should also be wisely ruled out. Nevertheless, viral, bacterial, parasitic, mycobacterial and fungal encephalitis should be excluded. COVID-19 encephalitis should be also considered in the differential diagnoses, particularly nowadays. Such life-threatening conditions need proper screening for all the above mentioned to avoid uninvited complications.

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations performed on admission

| Complete blood count | WBC: 5400 cells/cmm RBC: 4.48 million cells/cmm Haemoglobin: 130 g/L Hematocrit: 38.8% Platelets: 2 99 000 cells/cmm |

| Urea and electrolytes | Sodium: 138 mmol/L Potassium: 3.9 mmol/L Urea: 18 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.7 mg/dL |

| Nasopharyngeal swab | SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR for N gene, E gene, RDRP/ORF1ab: positive (detected) |

| CSF appearance | Clear and colourless |

| CSF cytology and microbiology | WBC: <5 cells/cmm RBC: 150 cells/cmm Gram stain: no organism is seen Culture: no growth Tuberculous PCR direct detection: Mycobacterium tuberculosis not detected |

| CSF virology | SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR (N gene, E gene, RDRP/ORF1ab): positive (detected) Herpes simplex virus I & II DNA PCR: negative Varicella zoster virus DNA PCR: negative Human herpes virus 6 DNA PCR: negative Human herpes virus 7 DNA PCR: negative Enterovirus RNA PCR: negative |

| CSF analysis | CSF protein: 45 mg/dL CSF glucose: 60 mg/dL CSF chloride: 119 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 0.42 µg/mL FEU |

| Bilirubin | Direct: 0.9 mg/dL Indirect: 2.1 mg/dL Total: 3.2 mg/dL |

| Liver function tests | Alkaline phosphatase: 73 U/L SGPT (ALT): 14 U/L AST: 33 U/L GGT: 11 U/L Total protein: 8.4 g/dL Albumin: 4.8 g/dL Globulin: 3.6 g/dL |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Non-reactive |

| Hepatitis C antibodies | Non-reactive |

| HIV 1&2 antigen and antibody | Non-reactive |

| HbA1c | 5.4% |

| Serum glucose (random) | 88 mg/dL |

| Vasculitis work-up | Thrombophilia screening, lupus anticoagulant, rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen profile, and anti-cardiolipin IgG and IgM are normal |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FEU, fibrinogen equivalent unit; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; RBC, red blood cell; SGPT, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; WBC, white blood cell.

Treatment

The patient was admitted in an isolated high dependency care unit. Primary care was initiated, including nasogastric tube and Foley’s catheter insertion, oxygen supplementation by nasal cannula, as well as intravenous fluids for the purpose of hydration.

The following treatment plan was decided on and was immediately started, and it included chloroquine 150 mg two times per day for 2 weeks, along with two tablets of lopinavir–ritonavir two times per day for 2 weeks. Seven hundred and fifty milligrams of intravenous acyclovir sodium, three times per day, was started empirically before the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results were obtained, addressing the possibility of herpes simplex virus (HSV) I and II encephalitis. The decision to continue the acyclovir for a further duration of 2 weeks was made, despite of the absence of evidence of HSV in the CSF, based on the fact that the patient was gradually improving, and there might be possibility of a false negative herpes simplex PCR CSF test.

Levetiracetam 1 g two times per day was started empirically, tackling the suspicion of non-convulsive seizure as a possible cause for the altered level of consciousness. In addition, 2 mg of intravenous lorazepam and 2.5 mg of intramuscular haloperidol two times per day were given as required, whenever needed.

Enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once a day and pantoprazole 40 mg daily were prescribed for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis and gastrointestinal prophylaxis, respectively. For supplementation, 10 mL of calcium–magnesium–D3–zinc (OSTEOCARE) 150 mg–75 mg–75 unit–3 mg/5 mL syrup was given as well.

After 1 week of his admission, the patient’s level of consciousness improved dramatically, despite his fluctuating confusion and agitation. The same management plan was resumed, except an increment in the enoxaparin dose to 70 mg subcutaneously two times per day was made, as a result of the patient’s elevated D-dimer levels of 2.6 mg/dL (table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory investigations performed 1 week after admission

| Bilirubin | Total: 3.0 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 2.65 µg/mL FEU |

FEU, fibrinogen equivalent unit.

The patient eventually became fully conscious and well coherent, with a complete resolution of his psychosis and agitation. After 2 weeks, he was successfully able to resume his normal life routine.

Outcome and follow-up

Fifteen days after admission, COVID-19 RNA PCR test was performed again on samples from both the nasopharynx and the CSF (table 3). Both results turned out to be negative. In addition, the bilirubin level improved as well.

Table 3.

Laboratory investigations performed 2 weeks after admission

| Nasopharyngeal swab | SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR (N gene, E gene, RDRP/ORF1ab): negative (not detected) |

| CSF appearance | Clear and colourless |

| CSF cytology and microbiology | WBC: <5 cells/cmm RBC: 50 cells/cmm Gram stain: No organism is seen Bacterial, fungal and AFB cultures: no growth |

| CSF virology | SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR (N gene, E gene, RDRP/ORF1ab): negative (not detected) Herpes simplex virus I & II DNA PCR: negative Varicella zoster virus DNA PCR: negative Human herpes virus 6 DNA PCR: negative Human herpes virus 7 DNA PCR: negative Enterovirus RNA PCR: negative |

| CSF analysis | CSF protein: 55 mg/dL CSF glucose: 67 mg/dL CSF chloride: 119 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 0.65 µg/mL FEU |

| Bilirubin | Total: 1.1 mg/dL |

AFB, acid-fast bacillus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FEU, fibrinogen equivalent unit; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

The patient was safely discharged from the hospital on 5 June 2020, retaining his normal baseline condition. On discharge, he was only prescribed vitamin C and zinc supplements. He did not require further anticoagulation as his D-dimer fell back to its normal limits and his pulmonary angiogram was unremarkable. A telephonic follow-up consultation was held with the patient, where he confirmed that he remains unquestionably in a good condition.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is acknowledged to affect the nervous system and induce polyneuropathy, encephalitis and acute ischaemic strokes.7 8 The mechanism by which coronavirus affects the CNS is not yet fully understood. It is sensible to agree that the mechanism of neuroinvasion could be either the traditional viral entry into CNS via circulating lymphocytes, or its entry via a permeable blood–brain barrier.3

One would debate that the acuteness of our patient’s neurological symptoms, as displayed in the symptomatology, brain imaging, as well as the elevated D-dimer, might suggest a viral influence on the vascular network of the CNS.

Nevertheless, the possible mechanism of injury of the brain’s vascular endothelium could be some disruption in the vascular structures, eventually leading to clotting and infarction.9–11 This, however, was not suggested in the presented case. A detailed look at the MRI of the brain (figures 3–5) study reveals an abnormal distribution that is symmetrical bilaterally, affecting mainly the frontal and temporal lobes. This picture highly suggests a viral pathology rather than a vascular insult.

As explained earlier, the behavioural changes, acute psychosis, acute confusional state and drowsiness were the initial and main presenting symptoms in a patient with COVID-19 without major respiratory symptoms, except for the self-limiting episode of mild cough that resolved spontaneously, prior to his presentation, without medical interference. The early suspicion of COVID-19 encephalitis and performing the appropriate CSF studies was the key to establishing the correct diagnosis and timely management.

Despite the absence of CSF pleocytosis, the suspicion of CNS encephalitis should still be considered. Upadhyayula suggested that viral meningoencephalitis may occur frequently in the lack of CSF pleocytosis.12 In addition, Erdem et al also suggested that the suspicion of CNS infections should not be underestimated despite the lack of CSF pleocytosis.13 There are also several published case series that described patients without CSF pleocytosis in relation to bacterial meningitis, herpes simplex encephalitis and enteroviral meningitis.14–16

Patients with meningoencephalitis associated with COVID-19 may not present with the commonly known flu-like illness, as with the presented patient.17

We conclude that early establishment of the diagnosis and the immediate commencement of a management plan may contribute to a better outcome.

Patient’s perspective.

When the doctors explained to me what happened and how COVID-19 affected my brain, I got terrified! I knew about the COVID-19 pandemic, but I couldn’t believe this happened to me! I am very blessed and grateful that I have received the necessary medical care and recovered completely from the COVID-19 infection. I, at some point, thought I lost my life. No words can express how I currently feel.

Learning points.

A red flag of the possibility of COVID-19 encephalitis should be raised whenever patients present with abnormal behaviour, acute psychosis, confusion state or drowsiness.

Prompt and specific investigations to diagnose this condition should not be hindered in absence of the more common respiratory COVID-19 symptoms such as anosmia, dysgeusia, flu-like symptoms, headache, and sensory or motor deficits.

Early diagnosis and management of such cases is important to avoid further undesired complications.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Raheel Ahmed for his assistance in direct patient care, as well as Dr Maria Khan, for the final review of the article.

Footnotes

Contributors: The contributors of this work include YMK for direct medical care and writing the structure of the article; YA for direct patient care, editing the article and the submission process; and AAAAM for direct patient care, as well as being the most responsible physician. We would also like to express our gratitude for the Infectious Disease team, the Psychiatry team and the nursing team in Rashid Hospital for helping us provide the complete medical care that the patient needs. Last but not least, we are thankful to the patient for consenting to publish his case.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus disease situation report. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/defaultsource/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200604-covid-19-sitrep-136.pdf?sfvrsn=fd36550b_2

- 2.Gaunt ER, Hardie A, Claas ECJ, et al. . Epidemiology and clinical presentations of the four human coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 detected over 3 years using a novel multiplex real-time PCR method. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:2940–7. 10.1128/JCM.00636-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steardo L, Steardo L, Zorec R, et al. . Neuroinfection may contribute to pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of COVID-19. Acta Physiol 2020;229:e13473. 10.1111/apha.13473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pilotto A, Odolini S, Masciocchi S, et al. . Steroid-Responsive encephalitis in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Neurol 2020 10.1002/ana.25783. [Epub ahead of print: 17 May 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, et al. . A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:55–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye M, Ren Y, Lv T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:945–6. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai L-K, Hsieh S-T, Chang Y-C. Neurological manifestations in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2005;14:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umapathi T, Kor AC, Venketasubramanian N, et al. . Large artery ischaemic stroke in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Neurol 2004;251:1227–31. 10.1007/s00415-004-0519-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. . Coronavirus disease 19 (Covid-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. . Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e38. 10.1056/NEJMc2007575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang T, Gao L, Lu J, et al. . ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas axis in brain: A potential target for prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013;11:209–17. 10.2174/1570159X11311020007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyayula S. 1823. incidence of meningoencephalitis in the absence of CSF pleocytosis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:S39 10.1093/ofid/ofz359.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdem H, Ozturk-Engin D, Cag Y, et al. . Central nervous system infections in the absence of cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis. Int J Infect Dis 2017;65:107–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan NWH, Lee EY, Khoo GMC, Hui Tan NW, Chin Khoo GM, et al. . Cerebrospinal fluid white cell count: discriminatory or otherwise for enteroviral meningitis in infants and young children? J Neurovirol 2016;22:213–7. 10.1007/s13365-015-0387-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin W-L, Chi H, Huang F-Y, et al. . Analysis of clinical outcomes in pediatric bacterial meningitis focusing on patients without cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2016;49:723–8. 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saraya AW, Wacharapluesadee S, Petcharat S, et al. . Normocellular CSF in herpes simplex encephalitis. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:1–7. 10.1186/s13104-016-1922-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Olama M, Rashid A, Garozzo D. COVID-19-associated meningoencephalitis complicated with intracranial hemorrhage: a case report. Acta Neurochir 2020;162:1495–9. 10.1007/s00701-020-04402-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]