Abstract

Purpose

To date, clinical data on real-world treatment practices in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) after bioprosthetic valve (BPV) replacement are needed. We conducted a large-scale, prospective, multicenter study to understand the actual usage of antithrombotic therapy and the incidence of thromboembolic and bleeding events in these patients, and to eliminate the clinical data gap between Japan and Western countries.

Methods

This was an observational study, in patients who had undergone BPV replacement and had a confirmed diagnosis of AF, with no mandated interventions. We report the baseline demographic and clinical data for the 899 evaluable patients at the end of the enrollment period.

Results

Overall, 45.7% of patients were male; the mean age was 80.3 years; AF was paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent in 36.9%, 34.6%, and 28.5% of patients, respectively. Mean risk scores for stroke and bleeding were 2.5 (CHADS2), 4.1 (CHA2DS2-VASc), and 2.5 (HAS-BLED). Many patients (76.2%) had comorbid hypertension and 54.8% had heart failure. Most BPVs (65.5%) were positioned in the aortic valve. Warfarin-based therapy, direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC)-based therapy, and antiplatelet therapy (without warfarin and DOAC) were administered to 55.0%, 29.3%, and 9.7% of patients, respectively.

Conclusion

Patients enrolled into this study are typical of the wider Japanese AF/BPV population in terms of age and clinical history. Future data accruing from the observational period will contribute to future treatment recommendations and guide therapeutic decisions in patients with BPV and AF.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: UMIN000034485

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10557-020-07038-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Valvular heart disease, Bioprosthetic valve replacement, Antithrombotic therapy, Thromboembolism, Bleeding

Introduction

Globally, it is estimated that 26 million people are affected by heart failure, and the disease places an enormous burden on health care facilities, resulting in more than one million hospitalizations per annum [1]. Valvular heart diseases, including degenerative aortic or mitral valves, or tricuspid valve dysfunction, are some of the most frequent causes of heart failure [2].

The number of operations for valvular heart disease in Japan continues to rise, with almost 12,500 aortic valve operations and 11,000 mitral valve operations performed in 2016 [3]. Among them, bioprosthetic valve (BPV) replacement was estimated to comprise just over 50% of valve replacement operations in 2016, and this is increasing year by year [3]. The concomitant presence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients undergoing valve replacement surgery adds additional complexity to treatment decisions [4].

Guidelines published in Europe and the United States consider AF patients with BPV as having non-valvular AF and recommend direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) treatment [5, 6]. In contrast, Japanese guidelines did not previously classify AF patients with BPV as non-valvular AF [7], but the classification of AF patients with BPV was changed from valvular to non-valvular AF in the recently revised Japanese guideline [8, 9]. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support these recommendations.

Among the published analyses of several large phase 3 trials comparing DOACs and warfarin in patients with valvular heart disease [10–13], only the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 [10] and ARISTOTLE [11] trials enrolled patients with BPV replacements. Unfortunately, the number of BPV cases available for evaluation was small, and although no differences in the incidence of stroke or systemic embolic events and major bleeding with either DOACs or warfarin were reported in either study, more robust clinical evidence is required. In addition, it has been suggested that individuals of Japanese or Asian ethnicity may have more bleeding events and lower rates of thromboembolism compared with Caucasian individuals [14]; thus, the data from the predominantly Caucasian patients in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 and ARISTOTLE may not be indicative of the clinical situation in Japan.

Recently, we reported the status and outcomes of patients with BPV replacement and AF in real-world clinical practice [15]. However, that analysis utilized a retrospective, observational design and had a relatively small sample size, and very few patients treated with DOACs were included.

The objective of this study was to collect more up-to-date data on treatment practices by conducting a large-scale, prospective, multicenter study. This will enable us to understand the actual usage of antithrombotic therapy and the incidence of events in patients with AF after BPV replacement in real-world Japanese clinical practice and to eliminate the clinical data gap between Japan and Western countries.

Methods and Analysis

Study Design and Assessments

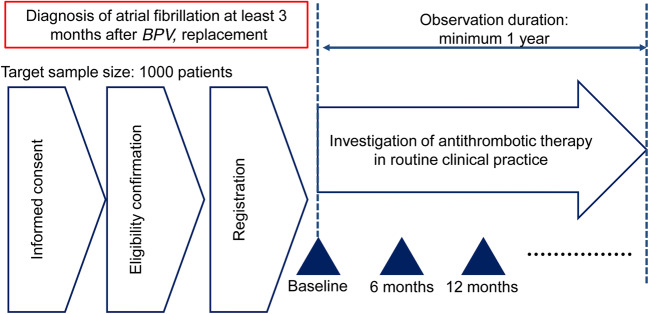

This is an ongoing, prospective, multicenter, observational, registry analysis. The study was initiated to understand the actual situation of antithrombotic therapy in daily clinical practice and the occurrence of prespecified efficacy and safety events during the study period. The planned study period is from September 2018 to May 2021. This includes an enrollment period of 1 year (September 2018 to October 2019) and an observation period of a minimum of 1 year (follow-up until October 2020) (Fig. 1). The study was registered at the University hospital Medical Information Network with the identification code UMIN 000034485.

Fig. 1.

Study design schematic, indicating the stages of enrollment and observation. BPV, bioprosthetic valve

As this is an observational study, no interventions were mandated as part of the study. Evaluation items are shown in Table 1. Observation, examination, and assessment items included patient background, medication administration status (antithrombotic drugs and other agents), invasive surgery status, blood coagulation test data, clinical course and laboratory tests, echocardiography, and adverse events. The risk of stroke was evaluated using the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2–VASc scores, and the risk of bleeding using the HAS-BLED score. These scores were calculated by the investigators using the medical record for each patient. Other background items of interest included smoking and drinking habits, and baseline medical comorbidities and complications. The position and type of BPV, type of surgery performed, and presence or absence of BPV revision were recorded, as was the AF classification (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent), bleeding or thromboembolic history, and all relevant treatment history. For patients receiving warfarin, prothrombin time and international normalized ratio (PT-INR) were measured. Adverse events were recorded using the Japanese Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities MedDRA/J version 23.0, along with the severity, outcome, and likely causation.

Table 1.

Details and timing of items evaluated during the study

| Item | Time point during study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Registration | Baselinea | Every 6 months (± 3 months) | |

| Confirmation of inclusion and exclusion criteria | ○ | ||

| Consent, visit status, and health check | ○ | ○ | |

| Patient characteristicsb | ○ | ||

| Antithrombotic drug status | ○ | ○ | |

| Administration status of medications other than antithrombotic drugsc | ○ | ○ | |

| Status of implementation of invasive procedures | ○ | ||

| Blood-clotting test (PT-INR)d,e | ○ | ○ | |

| Clinical course and laboratory teste | ○ | ○ | |

| Echocardiographyf | ○ | ○f | |

| Adverse eventsg | Throughout | ||

PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio

aBaseline was defined as the date of eligibility confirmation and enrollment in the study. If no data were available on the day of baseline, the most recent data were used, with the exception of echocardiogram, which used data immediately after the baseline (i.e., stabilized post-surgery)

bIncluded information on bioprosthetic valve replacement, atrial fibrillation, medical history, and complications/comorbidities

cIncluded antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, lipid-lowering drugs, antidiabetic agents, treatments for peptic ulcer (proton pump inhibitor, histamine H2 receptor antagonist), and P-glycoprotein inhibitors

dOnly patients receiving warfarin. The PT-INR data collected included up to the three most recent measurements at baseline and one measurement every 6 months

eData were collected only if implemented under routine clinical practice

fEchocardiography was performed every 1 year ± 6 months

gIncluded incidence of stroke, systemic embolism, hemorrhagic event, heart failure requiring hospitalization, and revision of bioprosthesis

The current analysis provides baseline demographic and clinical data for patients included in the study at the end of the enrollment period.

Patients and Eligibility Criteria

The target population for this study was patients who had undergone BPV replacement and had a confirmed diagnosis of AF. AF was defined as paroxysmal (return to sinus rhythm within 7 days of onset), persistent (persists for more than 7 days after onset), or permanent (electrically or pharmacologically non-defibrillable).

The detailed inclusion criteria were patients who underwent BPV replacement at least 3 months prior to enrollment (either aortic valve or mitral valve position, or both; replacement surgery could be either surgery or transcatheter aortic valve implantation); had a confirmed diagnosis of AF; had at least 1 year of follow-up data during the observation period; and had provided written consent. By requiring at least 3 months between surgery and enrollment, and including the criterion for a confirmed AF diagnosis, patients with transient postoperative AF were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were participation in or planned participation in any interventional study (to include pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventional therapy); moderate or severe mitral stenosis; mechanical valve replacement; and any other reason which meant that participation was judged inappropriate by the investigator. All patients, in either an inpatient or an outpatient setting, who consented to participate in the study, and who met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria, were enrolled in the study.

Study Endpoints

The study endpoints were defined as the occurrence of each prespecified event during the observation period (event rate). The primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of stroke or systemic embolism, and the primary safety endpoint was the occurrence of major bleeding (based on the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria [16]).

Secondary endpoints included the rates of the following events: stroke; systemic embolism; ischemic stroke; hemorrhagic stroke; intracranial hemorrhage; cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction, stroke, systemic embolism, and death from bleeding); and bleeding events (including clinically significant bleeding and minor bleeding).

Exploratory endpoints included the rates of the following events: heart failure requiring hospitalization; death from cardiovascular disease (i.e., death undeniably due to cardiovascular causes); all-cause mortality; and revision of bioprosthesis.

Statistical Analysis

Approximately 900 patients were assumed to be eligible for the study within 1 year of recruitment. In the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial, the incidence of stroke or systemic embolism event (primary efficacy endpoint) was 1.79% per year [10]. Assuming that the incidence of stroke or systemic embolism (primary efficacy endpoint) was 3% per year in 1000 patients, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the data obtained after a mean observation period of 1.0, 1.2, and 1.5 years will be ± 1.1%, ± 1.0%, and ± 0.9%, respectively.

Continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means and standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables were recorded as numbers and percentages. In future publications, incidence rates (per 100 patient-years) and 95% CIs of the primary efficacy and safety endpoints during the observation period will be calculated. The cumulative incidence rate of the primary efficacy and safety endpoints will be calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The point estimates of the hazard ratio and their 95% CIs will be calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model. The level of significance was set as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Nine hundred and twenty-eight patients were enrolled, of whom 28 patients did not meet the criteria and one patient withdrew. In total, 899 patients formed the analysis set for this study. Of these, 45.7% were male; the mean age was 80.3 years and the mean BMI was 22.2 kg/m2 (Table 2). The AF type was paroxysmal in 36.9% of patients, persistent in 34.6%, and permanent in 28.5%. The mean CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were 2.5 and 4.1, respectively, and the mean HAS-BLED score was 2.5. Frequently reported comorbidities (in ≥ 15% of patients) were hypertension (76.2%), heart failure (54.8%), dyslipidemia (49.4%), digestive disease (33.3%), hyperuricemia (25.8%), and diabetes mellitus (21.1%).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics at baseline, indicating demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | All (N = 899) | Warfarin-based therapy (n = 494) | DOAC-based therapy (n = 263) | Antiplatelet therapy (n = 87) | No antithrombotic drugs (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 411 (45.7) | 231 (46.8) | 105 (39.9) | 47 (54.0) | 28 (50.9) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 80.3 ± 7.0 | 79.5 ± 6.7 | 82.4 ± 6.5 | 79.7 ± 8.1 | 79.4 ± 8.2 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 53.8 ± 11.4 | 54.0 ± 11.3 | 53.4 ± 11.3 | 54.3 ± 12.1 | 53.7 ± 11.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 22.2 ± 3.7 | 22.1 ± 3.4 | 22.4 ± 4.2 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | 21.8 ± 3.8 |

| CHADS2 score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.1 |

| ≥ 2.0 | 678 (81.0) | 362 (78.5) | 219 (87.6) | 63 (80.8) | 34 (70.8) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 1.5 |

| ≥ 3.0 | 738 (87.8) | 397 (85.9) | 241 (95.3) | 61 (78.2) | 39 (81.3) |

| HAS-BLED score | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.1 |

| ≥ 3.0 | 376 (45.1) | 213 (46.5) | 101 (40.1) | 47 (60.3) | 15 (31.3) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 46.6 ± 17.7 | 45.5 ± 18.5 | 48.1 ± 14.8 | 47.8 ± 20.6 | 48.3 ± 18.1 |

| Ccr (mL/min) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 40.4 ± 18.3 | 40.2 ± 18.7 | 40.9 ± 16.4 | 39.1 ± 21.1 | 42.3 ± 20.5 |

| Type of AF | |||||

| Paroxysmal | 332 (36.9) | 121 (24.5) | 125 (47.5) | 56 (64.4) | 30 (54.6) |

| Persistent | 311 (34.6) | 196 (39.7) | 76 (28.9) | 24 (27.6) | 15 (27.3) |

| Permanent | 256 (28.5) | 177 (35.8) | 62 (23.6) | 7 (8.1) | 10 (18.2) |

| Previous history of CVD | |||||

| Ischemic stroke | 125 (13.9) | 58 (11.7) | 49 (18.6) | 15 (17.2) | 3 (5.5) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 21 (2.3) | 11 (2.2) | 6 (2.3) | 3 (3.5) | 1 (1.8) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 30 (3.3) | 13 (2.6) | 11 (4.2) | 4 (4.6) | 2 (3.6) |

| Systemic embolism | 11 (1.2) | 7 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Major bleeding | 47 (5.2) | 28 (5.7) | 9 (3.4) | 6 (6.9) | 4 (7.3) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 685 (76.2) | 356 (72.1) | 215 (81.8) | 74 (85.1) | 40 (72.7) |

| Heart failure | 493 (54.8) | 275 (55.7) | 145 (55.1) | 46 (52.9) | 27 (49.1) |

| Dyslipidemia | 444 (49.4) | 240 (48.6) | 135 (51.3) | 47 (54.0) | 22 (40.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 190 (21.1) | 110 (22.3) | 56 (21.3) | 18 (20.7) | 6 (10.9) |

| Renal dysfunction | 86 (9.6) | 52 (10.5) | 15 (5.7) | 13 (14.9) | 6 (10.9) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 86 (9.6) | 45 (9.1) | 31 (11.8) | 6 (6.9) | 4 (7.3) |

| Malignant tumor | 68 (7.6) | 31 (6.3) | 27 (10.3) | 6 (6.9) | 4 (7.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 45 (5.0) | 23 (4.7) | 7 (2.7) | 13 (14.9) | 2 (3.6) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 33 (3.7) | 15 (3.0) | 11 (4.2) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (9.1) |

| Thrombosis and embolism | 28 (3.1) | 13 (2.6) | 13 (4.9) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | |||||

| < 40% | 56 (6.7) | 43 (9.4) | 6 (2.4) | 5 (6.2) | 2 (3.9) |

| 40% to 49% | 73 (8.7) | 50 (10.9) | 14 (5.7) | 5 (6.2) | 4 (7.8) |

| ≥ 50% | 709 (84.6) | 367 (79.8) | 226 (91.9) | 71 (87.7) | 45 (88.2) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; Ccr, creatinine clearance; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation

Treatment

The prosthesis was positioned at the aortic valve in 65.5% of patients, at the mitral valve in 22.0% and at both valves in 25.0% (Table 3). Warfarin-based therapy was administered to 494 patients (55.0%), and 263 patients (29.3%) were treated with DOAC-based therapy. Antiplatelet therapy (without warfarin/DOAC) was administered to 87 patients (9.7%) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Operative characteristics describing the prosthesis position, and full details of the aortic and mitral valves

| Characteristic | All (N = 899) | Warfarin-based therapy (n = 494) | DOAC-based therapy (n = 263) | Antiplatelet therapy (n = 87) | No antithrombotic drugs (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthesis position | |||||

| Aortic valve | 589 (65.5) | 259 (52.4) | 221 (84.0) | 70 (80.5) | 39 (70.9) |

| Mitral valve | 198 (22.0) | 147 (29.8) | 31 (11.8) | 9 (10.3) | 11 (20.0) |

| Both valves | 112 (12.5) | 88 (17.8) | 11 (4.2) | 8 (9.2) | 5 (9.1) |

| Aortic valve | n = 589 | n = 259 | n = 211 | n = 70 | n = 39 |

| VHD subtype | |||||

| Stenosis | 445 (75.6) | 183 (70.7) | 186 (84.2) | 50 (71.4) | 26 (66.7) |

| Regurgitation | 114 (19.4) | 62 (23.9) | 28 (12.7) | 15 (21.4) | 9 (23.1) |

| Others | 30 (5.1) | 14 (5.4) | 7 (3.3) | 5 (7.1) | 4 (10.3) |

| Operation type | |||||

| Surgery | 352 (59.8) | 193 (74.5) | 79 (35.8) | 49 (70.0) | 31 (79.5) |

| TAVI | 237 (40.2) | 66 (25.5) | 142 (64.3) | 21 (30.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| History of replacement | |||||

| First replacement | 562 (95.4) | 242 (93.4) | 215 (97.3) | 68 (97.1) | 37 (94.9) |

| Re-replacement | 25 (4.2) | 16 (6.2) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (5.1) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mitral valve | n = 198 | n = 147 | n = 31 | n = 9 | n = 11 |

| VHD subtype | |||||

| Stenosis | 84 (42.2) | 66 (44.9) | 12 (38.7) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (36.4) |

| Regurgitation | 95 (48.0) | 67 (45.6) | 18 (58.1) | 4 (44.4) | 6 (54.6) |

| Others | 19 (9.7) | 14 (9.6) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (9.1) |

| Operation type | |||||

| Surgery | 198 (100.0) | 147 (100.0) | 31 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) |

| History of replacement | |||||

| First replacement | 174 (87.9) | 127 (86.4) | 29 (93.6) | 8 (88.9) | 10 (90.9) |

| Re-replacement | 24 (12.1) | 20 (13.6) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) |

Data are presented as n (%)

DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; VHD, valvular heart disease

Table 4.

Administration status of antithrombotic agents (anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs)

| Treatment agent | All (N = 899) |

|---|---|

| No antithrombotic drug | 55 (6.1) |

| Warfarin-based therapy | 494 (55.0) |

| No antiplatelet drug | 355 |

| With antiplatelet drug | 139 |

| With aspirin (monotherapy) | 121 |

| With P2Y12 (monotherapy) | 12 |

| With DAPT | 0 |

| With others | 6 |

| DOAC-based therapy | 263 (29.3) |

| No antiplatelet drug | 189 |

| With antiplatelet drug | 74 |

| With aspirin (monotherapy) | 54 |

| With P2Y12 (monotherapy) | 17 |

| With DAPT | 0 |

| With others | 3 |

| Antiplatelet therapy (without warfarin/DOAC) | 87 (9.7) |

| Aspirin (monotherapy) | 68 |

| P2Y12 (monotherapy) | 11 |

| DAPT | 4 |

| With others | 4 |

| Warfarin | n = 494 |

| PT-INR | |

| Age < 70 years | n = 27 |

| < 2.0 | 13 (52.0) |

| 2.0–3.0 | 12 (48.0) |

| > 3.0 | 0 (0.0) |

| Age ≥ 70 years | n = 467 |

| < 1.6 | 91 (21.6) |

| 1.6–2.6 | 293 (69.4) |

| > 2.6 | 38 (9.0) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified

DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; IQR, interquartile range; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy

Discussion

This prospective, observational study in 899 patients with AF who have undergone BPV replacement will provide clinically important data to physicians who are currently lacking robust evidence to guide treatment decisions in this patient population. This analysis of baseline data indicates that the patients enrolled into the study are typical of the wider Japanese AF/BPV population in terms of age and clinical history. As such, it is anticipated that future data accruing from the observational period, including the incidence of prespecified thromboembolic and bleeding events, will be widely generalizable and will contribute to future treatment recommendations and guide therapeutic decisions in patients with BPV and AF. In Japan, the validity of considering AF patients with BPV as having non-valvular AF has not been fully explored. Furthermore, clinical study data in this population are limited and come primarily from Caucasian patients [10, 11], which may not reflect the experience in Japanese clinical practice. Data in Japanese patients with AF who have undergone BPV implantation were recently reported from a small-scale retrospective analysis [15], but prospective analyses in the Japanese real-world clinical population are still required to fill the evidence gap. Moreover, although bleeding data have been reported for Asian patients living in the USA [14], it is widely accepted that residential location can have a strong influence on health outcomes (in terms of medical care, environment, and socioeconomic factors). Thus, it is important to observe Asian populations living in Asia to obtain geographically meaningful data.

In comparison with the recent publication from the retrospective BPV-AF registry, in which just 7.5% (16/214) of evaluable patients received DOACs [15], 29.3% (263/899) of patients in our study were found to be treated with DOAC-based therapy at baseline. This difference is likely owing to the timing of the two studies; in the retrospective analysis, we can infer a slow uptake of DOACs in the first few years after approvals were obtained, whereas a higher rate of DOAC prescription is found in current clinical practice. Low numbers of DOAC-treated patients in other AF studies [17–19] have made it difficult to draw accurate conclusions regarding outcomes. Furthermore, another study in which DOACs were administered to a large number of AF patients was restricted to a single area in Japan [20], which can confound the generalization of the data to the wider Japanese population, whereas the current analysis involves multiple study centers across Japan, potentially providing more relevant data for physicians.

Some previous studies have reported that thrombosis and bleeding tendencies differ between Japanese and Western populations [14, 21]. In published phase 3 trials in AF patients, the proportions of Asian patients were low (10.9% to 14.3% in ENGAGE-TIMI 48 [10] and 14.4% to 16.6% in ARISTOTLE [11]). In contrast, in our study, all enrolled patients were Japanese. Thus, our data are expected to suggest appropriate antithrombotic therapy for Asian AF patients.

Strengths and Limitations

The key strength of this study is the large-scale, prospective, multicenter design, enrolling real-world subjects with BPV, making it reflective of current clinical practice in Japan. We acknowledge that there may be bias inherent in the requirement for 1 year of follow-up data which results in the exclusion of patients with shorter data intervals who may have more severe complications. However, as the study was initiated after DOACs became available in Japan (the first approvals were obtained in 2011 [22]), it will provide the most up-to-date information on the usage of anticoagulants in the real world and deliver a counterpoint to the recent retrospective BPV-AF analysis [15].

Additionally, we did not specifically collect medical history data on percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting. Therefore, the risk of coronary events could potentially be underestimated because full information on the presence of coronary artery complications was not available for some patients. However, the CHA2DS2–VASc score was determined for each patient based on the information in the medical records. While the calculation of the score was dependent on the information in the medical records, we believe that the CHA2DS2–VASc score is unlikely to be underestimated because it includes complications of coronary artery disease other than a history of myocardial infarction.

Conclusions

This prospective analysis of 899 patients with AF and BPV replacement in Japanese clinical practice will provide much-needed information to evaluate therapeutic decisions and potential outcomes in this patient population. The baseline data analysis indicates that the study population is typical of AF/BPV patients in Japan, and the outcome data from the observation period are eagerly awaited.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 16 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally-Anne Mitchell, PhD, of Edanz Medical Writing for providing medical writing support which was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Yutaka Furukawa, Makoto Miyake, and Chisato Izumi contributed to data collection. Data analysis was performed by Misa Takegami and Kunihiro Nishimura. The manuscript was drafted by Yutaka Furukawa and Chisato Izumi, and critically revised by all authors; all authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding Information

This study was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) in collaboration with the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center. The sponsor was involved in the preparation of the study protocol and planning the analyses, but was not directly involved in data collection, management, or calculations.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request, and with permission of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Competing Interests

Yutaka Furukawa has received honoraria as a consultant or speaker from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. Tadaaki Koyama has received personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Tetsuya Kimura, Kumiko Sugio and Atsushi Takita are employees of Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. Kunihiro Nishimura has received research funding from Philips Japan Ltd., Terumo Corporation, Tokyo Electric Power Company, P&G Japan, and Asahi Kasei Pharma. Chisato Izumi has received grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and personal fees from Edwards Lifescience Co., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Makoto Miyake, Tomoyuki Fujita, and Misa Takegami declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in compliance with the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and all other local, national, or international regulatory and legal requirements. The protocol and the informed consent document/form were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of each participating medical institution.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written informed consent for participation before study entry.

Footnotes

Details of all investigators in the BPV-AF Registry group are provided in Online Resource 1.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, Nodari S, Lam CSP, Sato N, Shah AN, Gheorghiade M. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabata N, Sinning JM, Kaikita K, Tsujita K, Nickenig G, Werner N. Current status and future perspective of structural heart disease intervention. J Cardiol. 2019;74:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee for Scientific Affairs The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery; Shimizu H, Endo S, et al. Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in Japan in 2016: annual report by the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;67:377–411. doi: 10.1007/s11748-019-01068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh K, Dizon J, Biviano A. Revisiting atrial fibrillation in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement era. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2018;7:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.iccl.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener HC, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, Hindricks G, Manolis AS, Oldgren J, Popescu BA, Schotten U, van Putte B, Vardas P, Agewall S, Camm J, Baron Esquivias G, Budts W, Carerj S, Casselman F, Coca A, de Caterina R, Deftereos S, Dobrev D, Ferro JM, Filippatos G, Fitzsimons D, Gorenek B, Guenoun M, Hohnloser SH, Kolh P, Lip GYH, Manolis A, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, Rosenhek R, Ruschitzka F, Savelieva I, Sharma S, Suwalski P, Tamargo JL, Taylor CJ, van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zeppenfeld K. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140:e125–e151. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.JCS Joint Working Group Guidelines for pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation (JCS 2013) Circ J. 2014;78:1997–2021. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-66-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono K, Iwasaki Y, Shimizu W, et al. JCS/JHRS 2020 Guideline on pharmacotherapy of cardiac arrhythmias. The Japanese Circulation Society / Japanese Heart Rhythm Society Joint Guidelines. Available at: http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/pdf/JCS2020_Ono.pdf [In Japanese]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Izumi C, Eishi K, et al. JCS/JATS/JSVS/JSCS 2020 Guideline on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease. The Japanese Circulation Society / The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery / the Japanese Society for Vascular Surgery / The Japanese Society for Cardiovascular Surgery Joint Guidelines. Available at: http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/pdf/JCS2020_Izumi_Eishi.pdf [In Japanese].

- 10.De Caterina R, Renda G, Carnicelli AP, et al. Valvular heart disease patients on edoxaban or warfarin in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1372–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avezum A, Lopes RD, Schulte PJ, Lanas F, Gersh BJ, Hanna M, Pais P, Erol C, Diaz R, Bahit MC, Bartunek J, de Caterina R, Goto S, Ruzyllo W, Zhu J, Granger CB, Alexander JH. Apixaban in comparison with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: findings from the apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial. Circulation. 2015;132:624–632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnicelli AP, De Caterina R, Halperin JL, et al. Edoxaban for the prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation and bioprosthetic valves. Circulation. 2017;135:1273–1275. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezekowitz MD, Nagarakanti R, Noack H, Brueckmann M, Litherland C, Jacobs M, Clemens A, Reilly PA, Connolly SJ, Yusuf S, Wallentin L. Comparison of dabigatran and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: the RE-LY trial (randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy) Circulation. 2016;134:589–598. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen AY, Yao JF, Brar SS, Jorgensen MB, Chen W. Racial/ethnic differences in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izumi C, Miyake M, Amano M, et al. Registry of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients with bioprosthetic valves: a retrospective observational study. J Cardiol. 2020;76:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on control of anticoagulation of the scientific and standardization committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atarashi H, Inoue H, Okumura K, J-RHYTHM Registry Investigators et al. Present status of anticoagulation treatment in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the J-RHYTHM Registry. Circ J. 2011;75:1328–1333. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akao M, Chun YH, Wada H, Fushimi AF Registry Investigators et al. Current status of clinical background of patients with atrial fibrillation in a community-based survey: the Fushimi AF Registry. J Cardiol. 2013;61:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki S, Yamashita T, Okumura K, Atarashi H, Akao M, Ogawa H, Inoue H. Incidence of ischemic stroke in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation not receiving anticoagulation therapy-pooled analysis of the Shinken Database, J-RHYTHM Registry, and Fushimi AF Registry. Circ J. 2015;79:432–438. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okumura Y, Yokoyama K, Matsumoto N, the Sakura AF Registry Investigators et al. Current use of direct oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation in Japan: findings from the SAKURA AF Registry. J Arrhythm. 2017;33:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumasaka N, Sakuma M, Shirato K. Incidence of pulmonary thromboembolism in Japan. Jpn Circ J. 1999;63:439–441. doi: 10.1253/jcj.63.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ieko M, Naitoh S, Yoshida M, Takahashi N. Profiles of direct oral anticoagulants and clinical usage-dosage and dose regimen differences. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:19. doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request, and with permission of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center and Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.