(Cell 182, 843–854.e1–e12; August 20, 2020)

We discovered that values for 2 out of 79 antibodies have unfortunately been wrongly reported. For antibody FnC1t1p2_A5, the IC100 is 50 μg/mL instead of 16 μg/mL; for antibody CnC2t1p1_B10, the IC100 is >100 μg/mL instead of 12.5 μg/mL. For the latter antibody, binding characteristics were also corrected. As a consequence, the total number of neutralizing antibodies reported is 27 instead of 28. Changes affect Figures 3, 4, S3, S4, and S5, Tables S3 and S4, and text on pages 1, 3, 5, and 7. Importantly, the corrections have no impact on the conclusions in this paper. We apologize for any inconvenience that may have been caused by this error.

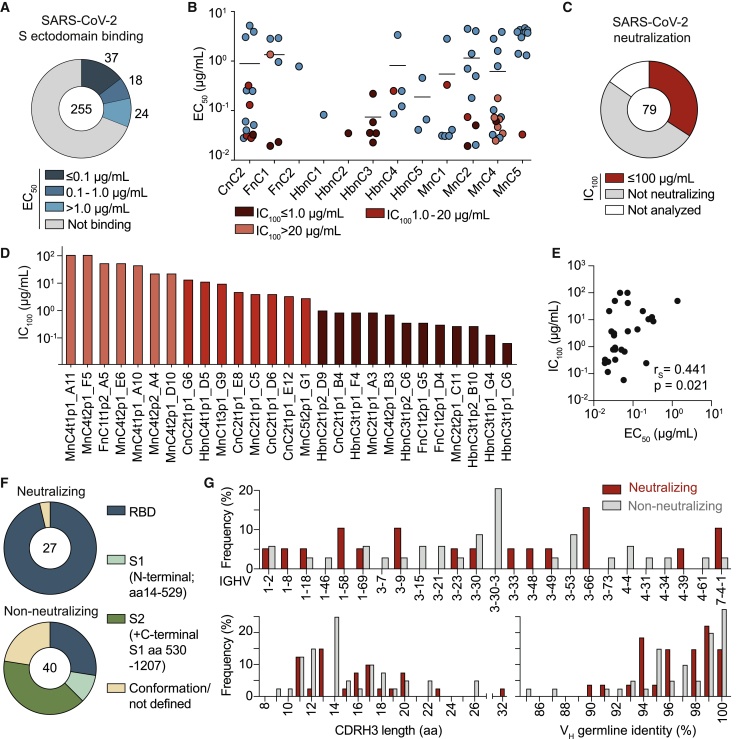

Figure 3.

Infected individuals can develop potent near-germline SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies that preferentially bind to the S-protein RBD (corrected)

Figure 3.

Infected individuals can develop potent near-germline SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies that preferentially bind to the S-protein RBD (original)

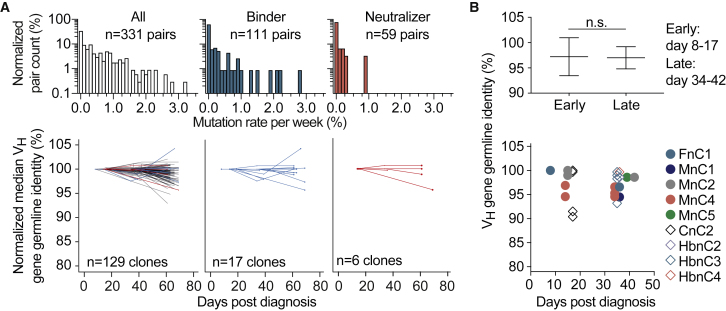

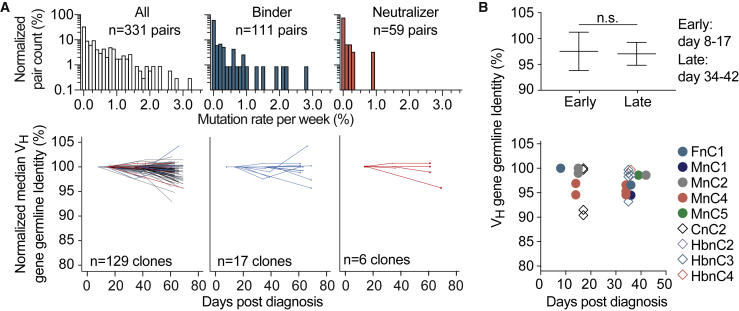

Figure 4.

Dynamics of somatic mutations for SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies (corrected)

Figure 4.

Dynamics of somatic mutations for SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies (original)

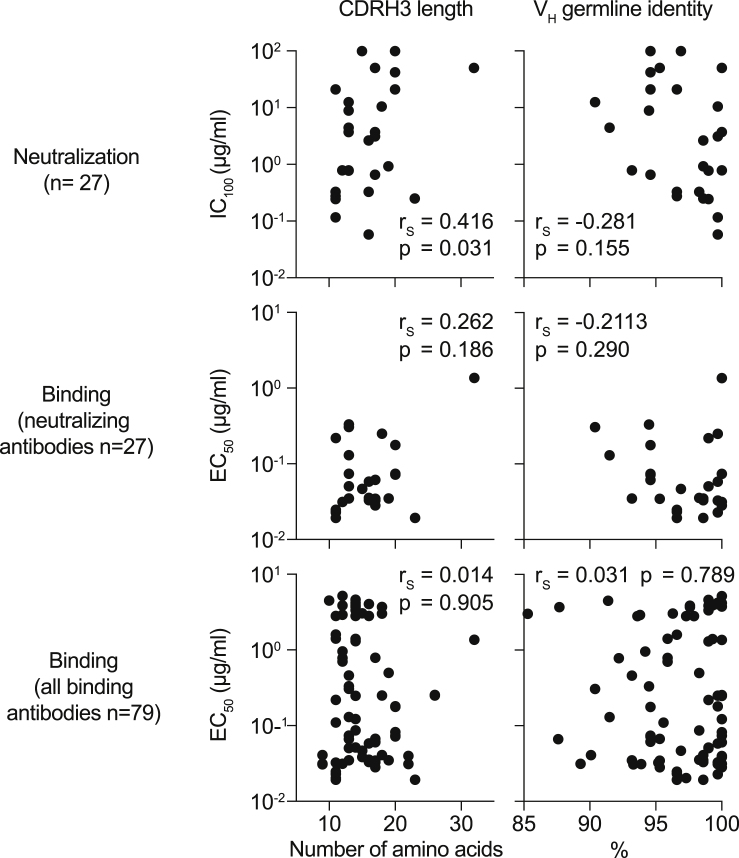

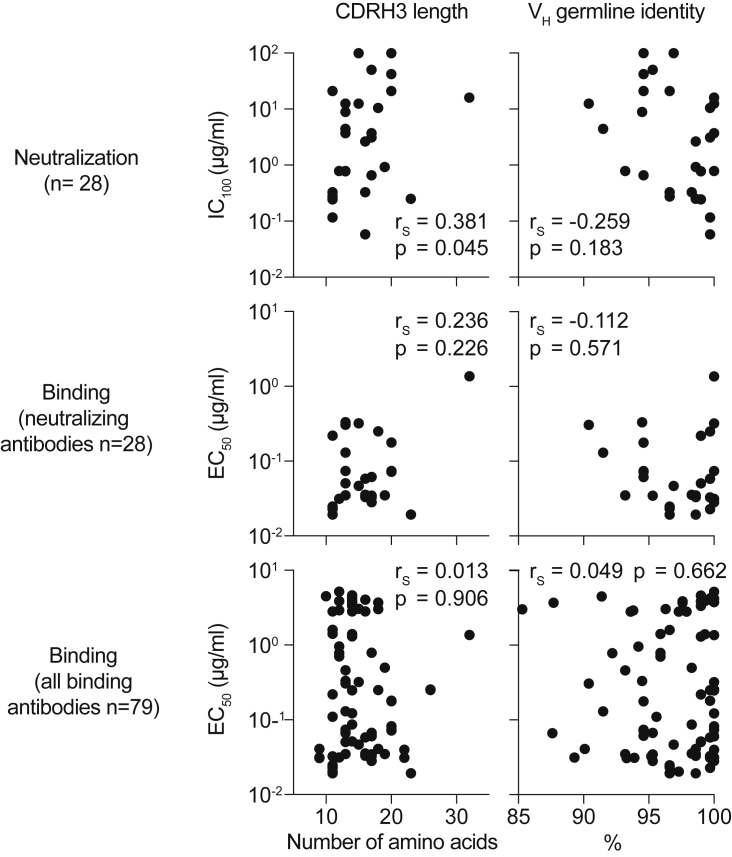

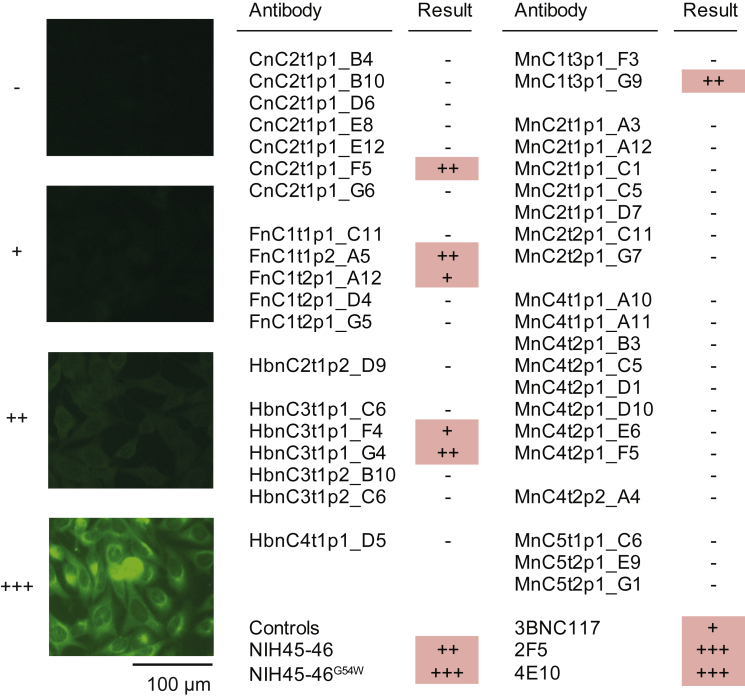

Figure S3.

Correlation of binding and neutralization with VH gene characteristics (corrected)

Figure S3.

Correlation of binding and neutralization with VH gene characteristics (original)

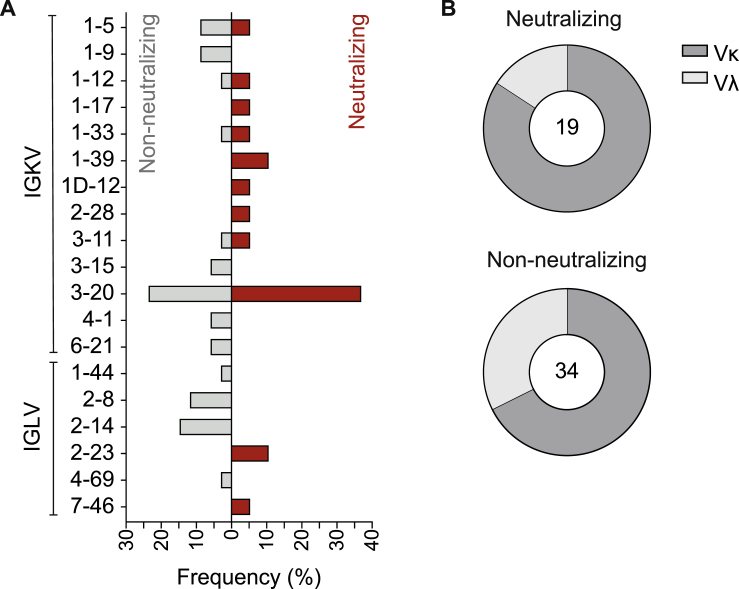

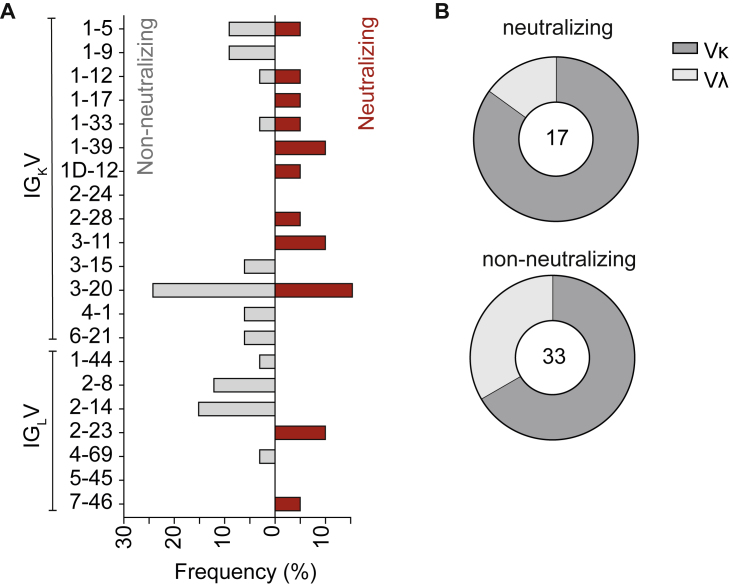

Figure S4.

VL gene distribution in non-neutralizing and neutralizing antibodies (corrected)

Figure S4.

VL gene distribution in non-neutralizing and neutralizing antibodies (original)

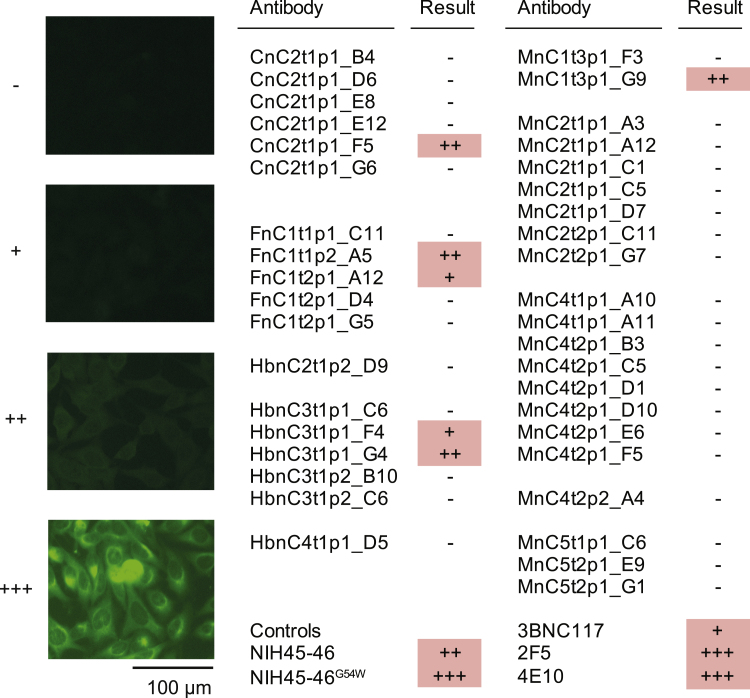

Figure S5.

Autoreactivity of selected SARS-CoV-2-binding and -neutralizing antibodies (corrected)

Figure S5.

Autoreactivity of selected SARS-CoV-2-binding and -neutralizing antibodies (original)