Abstract

Objective: We aimed to determine the therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) features and the relation to Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) of frequently used new antiepileptic drugs (NADs) including lamotrigine (LTG), oxcarbazepine (OXC), zonisamide (ZNS) and lacosamide (LCM). Moreover, we investigated their effect on the quality of life (QoL).

Methods: Eighty epileptic patients who had been using the NADs, and thirteen healthy participants were included in this cross-sectional study. The participants were randomized into groups. The QOLIE-31 test was used for the assessment of QoL. We also prepared and applied “Safety Test”. HPLC method for TDM, and ELISA method for BDNF measurements were used consecutively.

Results: In comparison to healthy participants, epileptic participants had lower marriage rate (p=0.049), education level (p˂0.001), alcohol use (p=0.002). BDNF levels were higher in patients with focal epilepsy (p=0.013) and in those with higher education level (p=0.016). There were negative correlations between serum BDNF levels and serum ZNS levels (p=0.042) with LTG-polytherapy, serum MHD levels (a 10-monohydroxy derivative of OXC, p=0.041) with OXC-monotherapy. There was no difference in BDNF according to monotherapy-polytherapy, drug-resistant groups, regarding seizure frequency. There was a positive correlation between total health status and QoL (p˂0.001). QOLIE-31 overall score (OS) was higher in those with OXC-monotherapy (76.5±14.5). OS (p˂0.001), seizure worry (SW, p=0.004), cognition (C, p˂0.001), social function (SF, p˂0.001) were different in the main groups. Forgetfulness was the most common unwanted effect.

Conclusion: While TDM helps the clinician to use more effective and safe NADs, BDNF may assist in TDM for reaching the therapeutic target in epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, new antiepileptic drugs, TDM, safety, QOLIE-31, BDNF, efficacy

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to the cognitive, psychological, economic, social consequences of epilepsy, improper treatment may severely reduce patient's Quality of Life (QoL). Therefore, QoL assessment is recommended together with prescribed treatment [1]. Epilepsy treatment is based on pharmacological treatment. The recent guideline report shows that the use of New Antiepileptic Drugs (NADs) is increased in clinical practice [2]. Thus, identifying the differences between the NADs in the pharmacological treatment and their effect on QoL, using a multi-treatment approach in the clinic is required. Common problems in epilepsy treatment include the difficulty of choosing the appropriate drug, multiple drug use, drug-interactions, pharmacoresistance, comorbidities, and concomitant medications. These points create limitations particularly in generalized epilepsy and cause an increase in unwanted effects and the treatment cost [3]. Thus, using Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM), a rational tool contributing to the therapeutic success, with the new technologies in the outpatient/inpatient clinic, establishing personalized treatment options for more efficient and safe utilization of NADs, and identifying NADs' TDM characteristics are needed [4]. Utilized for the first time for Old Antiepileptic Drugs (OADs), TDM came into use in Turkey in the 1980s [5]. Although NADs' TDM characteristics and contributions to the clinical routine are not well-known, a small number of studies indicate TDM's importance and the need to improve TDM [6, 7].

Nevertheless, the search for new molecules continues, and research on new biomarkers, nanotechnology and is gaining momentum [8, 9]. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), an important biomarker in neuroplasticity development, is a small protein encoded by the human BDNF gene. It has roles in the neuronal survival in the central, peripheral nervous system, and growth, differentiation of the new neurons, synapses during brain development [10]. BDNF is neuroprotective and active in the hippocampus, cortex, and basal forebrain. BDNF dysregulation relates neuropsychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder, dementia, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), late-stage Alzheimer's, autism, Multiple Sclerosis (MS), mainly depression [11] and there are few studies on epilepsy, Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs) and BDNF. The relationship between serum BDNF and serum drug levels is important [12]. Identifying BDNF's potential clinical roles in epileptic patients will contribute to TDM of current AEDs and developing more effective and safe NADs [13].

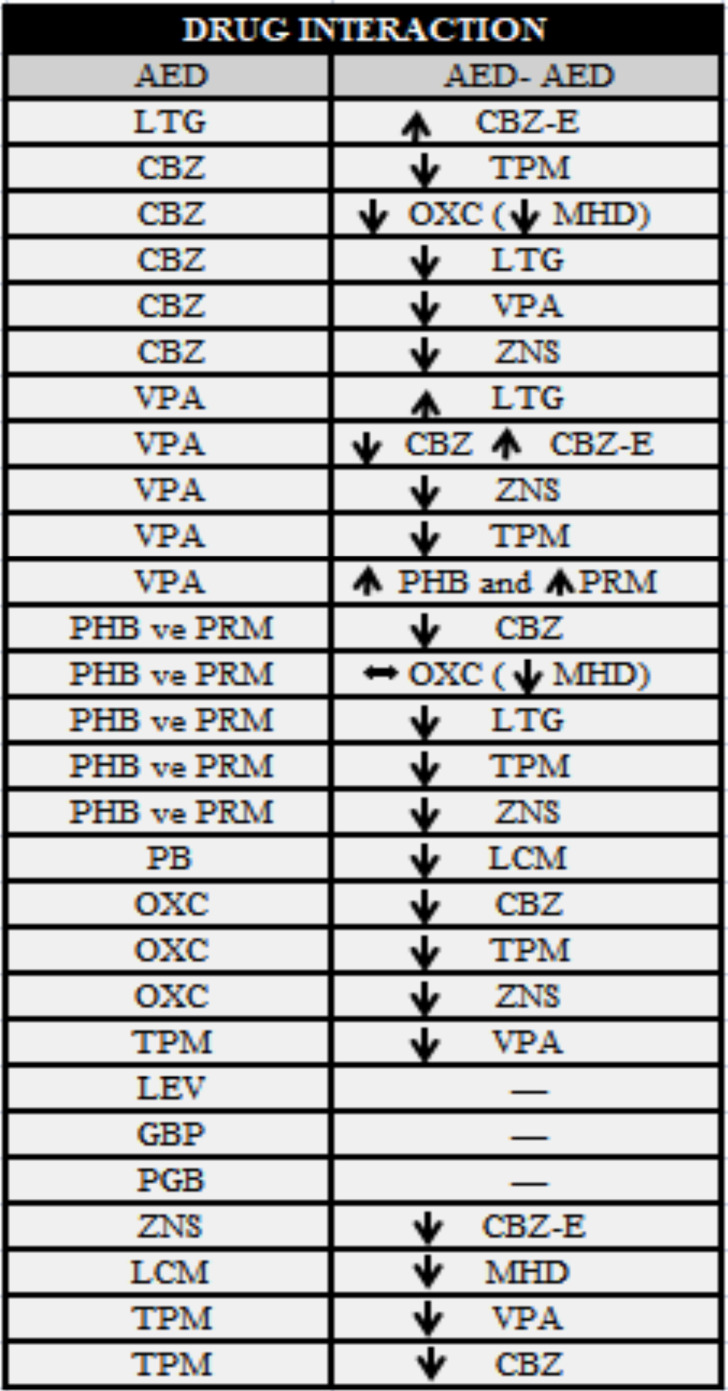

The aim of this clinical study is to monitor the serum levels of NADs [lamotrigine (LTG), oxcarbazepine (OXC), lacosamide (LCM), zonisamide (ZNS)], as well as OADs [carbamazepine (CBZ), primidone (PRM), phenobarbital (PB)] simultaneously, within a short period such as 9-15 minutes and contribute to the clinical routine by identifying their TDM characteristics. This method will be rational, fast and pharmacoeconomic, beneficial for the health economy, and with the newly developed “Safety Test”, a sample model to investigate unwanted effects, drug interactions, and establish a safety database is intended. Another aim is to determine the differences between and superiorities of NADs on the QoL. Finally, it was aimed to look at all potential relationships of BDNF in epileptic-nondepressed patients for improving the monitoring of the safety and therapeutic efficacy and contributing an important step for developing NAD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Participants

We screened all patients treated with any NAD medication who were admitted to the outpatient clinics of our Neurology Department. Male/female patients aged 18-60 years, who were using the NAD (LTG, OXC, ZNS, or LCM) for one month with a stable dose regimen were included. The patients who had a previous organ dysfunction, any chronic inflammatory disease, Major Depression Disorders (MDD) or other psychiatric diseases, those using antidepressants, having other pathology of the Central Nervous System (CNS) or abused any substance and/or alcohol, pregnant and lactating women, noncompliant patients were excluded. Healthy participants who underwent therapy/medicine with a history of febrile seizures, pregnant and lactating women, using herbal products were also excluded.

2.2. Study Protocol

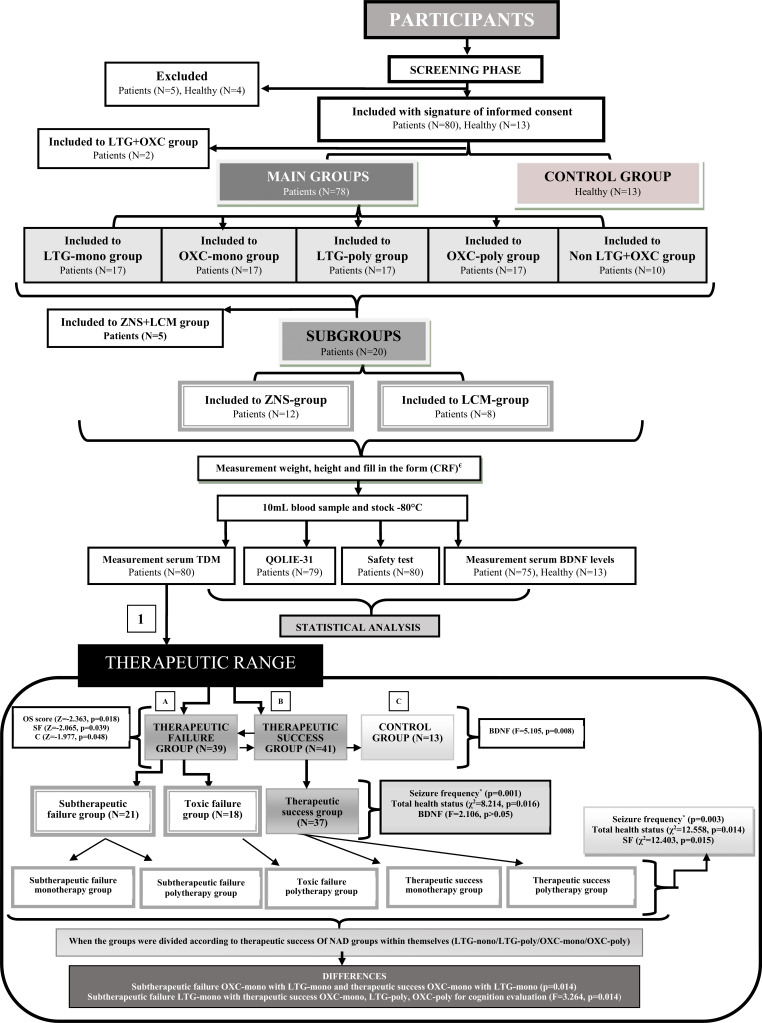

Participants in this cross-sectional study were divided into five main groups and two subgroups as accepted by physicians, whose treatment reached the target: 1) participants whose treatment consisted predominantly of a lamotrigine monotherapy (LTG-mono group), 2) participants whose treatment consisted predominantly of a lamotrigine polytherapy (LTG-poly group) 3) participants whose treatment consisted predominantly of an oxcarbazepine monotherapy (OXC-mono group), 4) participants whose treatment consisted predominantly of an oxcarbazepine polytherapy (OXC-poly group) and 5) patients whose treatment did not include lamotrigine or oxcarbazepine therapy (non LTG+OXC group). The subgroups patients were taking A) zonisamide polytherapy (ZNS-group) and B) lacosamide polytherapy (LCM-group). These patients were selected in the main groups. The polytherapy patients were taking LTG, OXC, CBZ, ZNS, LCM, PB, PRM, Valproic Acid (VPA) clobazam (CLB), topiramate (TPM) or levetiracetam (LEV), pregabalin (PGB); gabapentin (GBP) drugs in different combinations dosages but the dosing of each medication was stable for the one month preceding the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Study design with therapeutic success for AEDs. 1; All participants were divided into there groups: A) successfull in the therapeutic range, B) failure in the therapeutic range, C) control group. Therapeutic successfull group values were high. ±Total health status, OS, SF and C values were higher therapeutic success groups according to toxic failure groups. Control group was added to the each binary, triple and quinary groups for only BDNF comparisons. *Fisher exact test. €All participants. CRF; CASE Report Form, AED; Antiepileptic Drug NAD; New Antiepileptic Drug, OAD; Old Antiepileptic Drug, OD; Other Drug, Mono; Monotherapy, Poly; Polytherapy, BDNF; Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, SW; Seizure Worry, OQOL; Overall Quality of Life, EWB; Emotional Well-Being, EF; Energy/Fatigue, C; Cognitive, ME; Medication Effects, SF; Social function, OS; Overall score, TDM; Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. AED; Antiepileptic Drug NAD; New Antiepileptic Drug, BDNF; brain-derived neurotropic factor, cognitive (C), social function (SF), overall score (OS).

Secondly, the participants were grouped separately both in the presence of unwanted effects, drug interactions, therapeutic success and control. A detailed medical history including seizure semiology was taken, a complete physical examination was performed on all patients. We included the age of onset, etiology, syndromes according to 2010 ILAE classification [14], number of the seizure of the patients. We investigated laboratory test results including PLT, AST, ALT, WBC, creatinine. We also measured weight, height and compared demographic data of all participants.

2.3. Sample Collection and Analysis

A blood sample of 10 mL was taken via peripheral venous access in the sitting position between 7.30-13.30 am. The blood sample was taken into a red top tube to avoid interaction. We selected blood sampling time in the trough concentration. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 20 minutes at 1000xg. We separated the serum portions. Then, aliquots were stored at −80°C, and later analyzed in one batch. Serum BDNF levels were measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, ELx 800 reader) and then, we calculated concentrations on the standard curve. Serum TDM was measured With High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) technique from serum obtained from the centrifuged blood samples. HPLC kit is specific for AEDs and we measured LTG, OXC, MHD (10-monohydroxy derivative of oxcarbazepine), ZNS, LCM, PRM, PB, CBZ, carbamazepine-10, 11-epoxide (CBZ-E) with the kit at the same time [15] in this study. We measured the AEDs in 9 minutes, but only CBZ level was measured in 15 minutes. Concentrations of OXC’s metabolites (MHD) were measured by means of HPLC methods. Four patients used VPA additionally and therefore VPA levels result was recorded from the last month from the patients’ files. LEV, PGB and GBP had no known drug interactions with other AED. LEV, TPM, PGB and GBP levels were not measured. Only one patient used PGB, GBP, CLB and four patients used TPM in all study groups.

2.4. Assessment of the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31)

Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31) is the QoL survey consisting of 31 items and questions only about epilepsy issues. The QOLIE-31 scale has gained scale characteristics with the last item evaluating total health status (31st) without normally consisting of 30 items of 7 subscales. The QOLIE-31 scale is scored between 0 and 100 [16]. T-scores were computed using the different formula for standardization. The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the QOLIE-31 were published by Mollaoğlu et al [17]. The test assesses QoL including seizure worry (SW), overall QoL (OQOL), emotional well-being (EWB), energy/fatigue (EF), cognitive (C), medication effects (ME), social function (SF), overall score (OS), total health status and T-scores [16]. Patients with a QOLIE-31 total score (OS) of ≥50 were considered to have wellness [16, 17].

2.5. Efficacy and Safety Endpoints

Efficacy evaluation was made according to the results of TDM in therapeutic range and treatment answers were related to seizure frequency, using Other Drugs (ODs), laboratory findings, the basic demographic characteristics, clinical interpretation together.

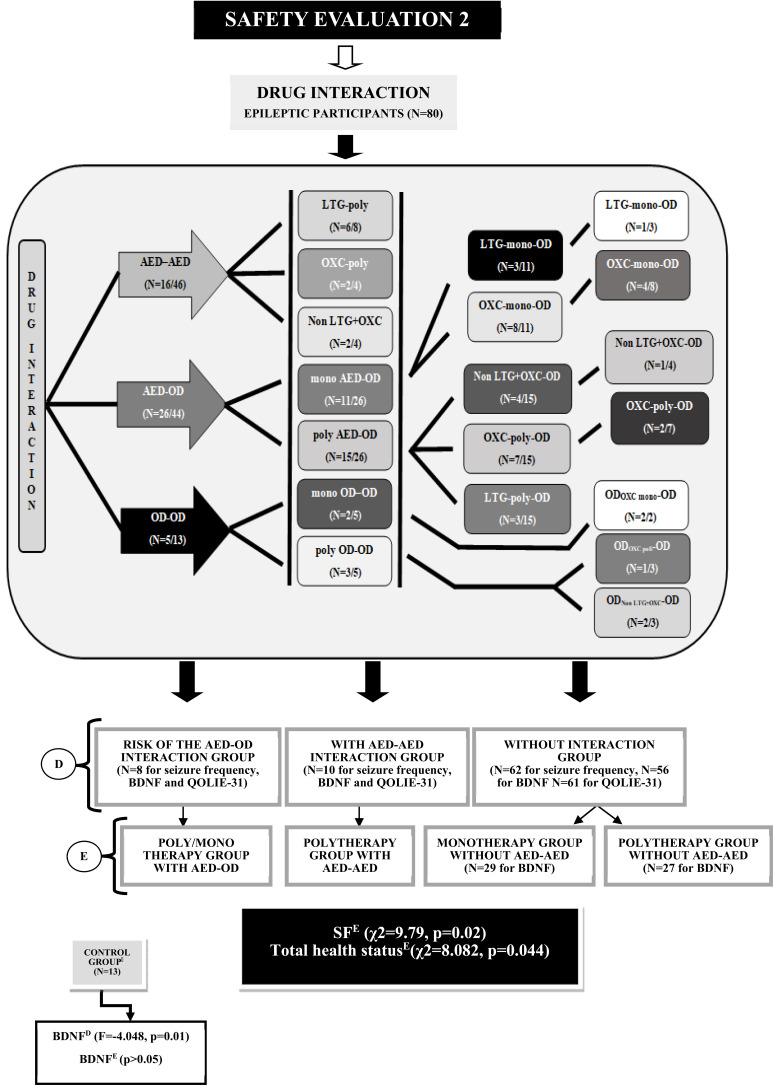

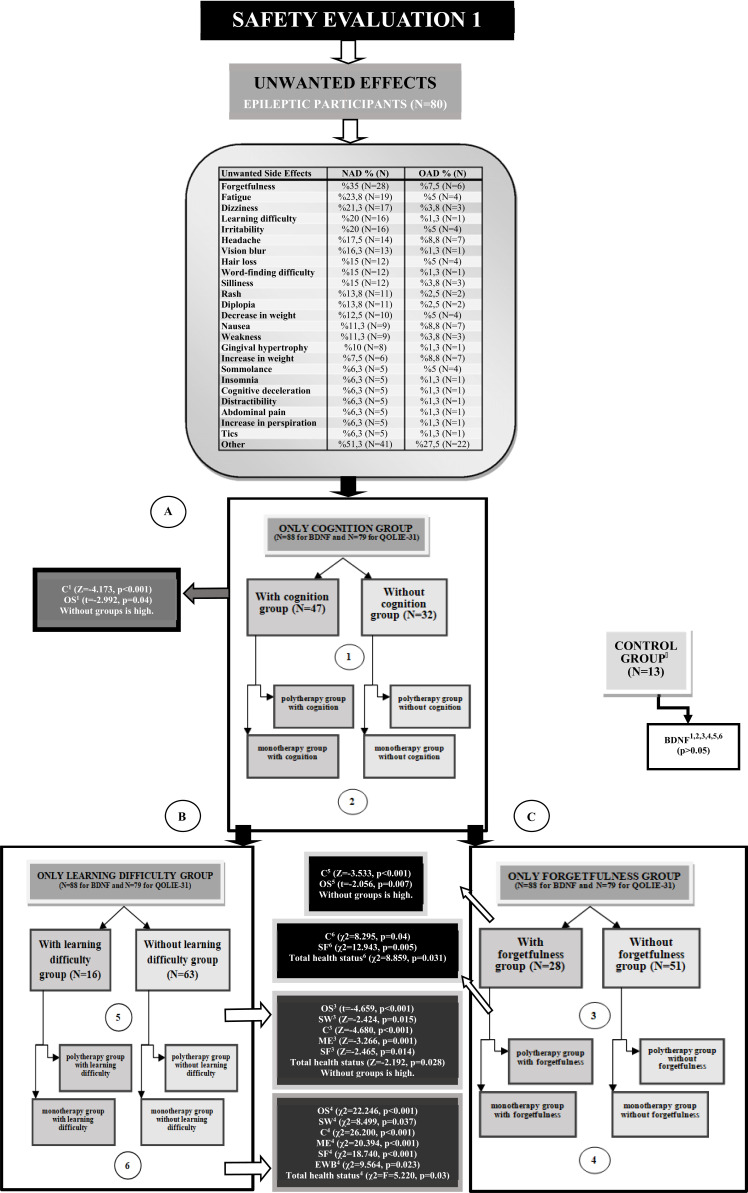

“Safety Test” was prepared for unwanted effects, used for patient, and then recorded to encountered only minor unwanted side effects. Also, the findings were compared with previous reports and databases [18]. Safety evaluation was made according to the results of TDM to toxic levels, drug-interactions (Appendix e-1), other variables, the safety test results and overall clinical interpretation together. Also, all patients were divided into therapeutic success/failure group for TDM (Figs. 1-3).

Fig. (3).

Safety evaluation and comparison for drug interactions. D; All participants were divided into four groups: D1) risk of AED-OD interaction owner, D2) AED-AED inrecation owner, D3) drug inrecation not owner, D4) control group. E; All participants were divided into five groups: E1) risk of AED-OD interaction owner, E2) AED-AED inrecation owner, E3) drug inrecation not owner in monotherapies, E4) drug inrecation not owner in polytherapies, E5) control group. Control group was added to the each binary and quaternary groups for only BDNF comparisons and user ANOVA test. AED; Antiepileptic Drug NAD; New Antiepileptic Drug, OAD; Old Antiepileptic Drug, OD; Other Drug, Mono; Monotherapy, Poly; Polytherapy, BDNF; Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, SW; Seizure Worry, OQOL; Overall Quality of Life, EWB; Emotional Well-Being, EF; Energy/Fatigue, C; Cognitive, ME; Medication Effects, SF; Social function, OS; Overall score.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were given as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). The conformity to the normal distribution was investigated with the Shapiro-Wilks test. The variables showing a normal distribution were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)/student t-test, whereas the others were evaluated with Kruskal-Wallis/Mann Whitney U tests. Chi-square and Freeman-Halton Extension of Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. The relationship between continuous variables was investigated with Pearson (r) or Spearman's rho correlation coefficient. A value of p<0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 21.0 statistical package for Windows.

2.7. Data Availability

This study is the doctorate thesis project of Meral Demir. Baseline data are online (https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp), and follow-up data are available to qualified investigators on request to the corresponding author.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Eighty (56.5% female, 43.5% male) consecutive patients who received NAD treatments, and 13 healthy participants (53.8% female, 46.2% male) were included. Five patients, four healthy participants who had not complied with this research protocol were excluded. The mean age of all participants is 34.4±10.6 years. There were differences in education (p<0.001), marital status (p=0.049), using alcohol (p=0.002) between patients and controls. The demographic and clinical characteristics, epilepsy features and basic laboratory findings are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the participants and correlation for TDM and BDNF level.

| Groups | Maingroups | Subgroups | Total | Control Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value 1 |

LTG-mono

(N=17) |

LTG-poly (N=17) | OXC-mono (N=17) | OXC-poly (N=17) | Non LTG+OXC (N=10) |

ZNS

(N=12) |

LCM

(N=8) |

Total patients (N=80) | Control (N=13) |

| AGE (year) | 31.1±10.7 | 34.6±9.6 | 32.7±13.2 | 36.3±11.1 | 35.5±11.7 | 33.9±10.3 | 35.2±9.0 | 34.4±10.6 | 36.7±7.3 |

| HEIGHT (cm) | 166.5±10.0 | 160.7±13.0 | 166.3±9.1 | 169.2±5.7 | 165.4±9.6 | 167.1±8.4 | 163.7±14.7 | 166.4±10.1 | 170.1±11.1 |

| WEIGHT (kg) | 71.7±16.2 | 69.0±18.6 | 69.4±15.3 | 69.1±12.9 | 67.4±17.6 | 70.5±14.9 | 68.9±21.8 | 70.9±15.8 | 78.3±16.3 |

| WBC (10ʌ3/µL) | 7.0±1.2 | 6.3±1.3 | 7.3±1.2 | 7.6±3.8 | 6.2±2.0 | 6.5±1.5 | 7.6±1.3 | 6.9±2.0 | 6.4±1.8 |

| PLT 10ʌ3/µL) | 254.5±37.8 | 241.9±67.0 | 256.4±57.2 | 255.3±58.8 | 226.4±39.0 | 253.6±65.3 | 259.5±61.4 | 250.3±54.7 | 219.5±6.4 |

| AST (U/L) | 17.6±3.0 | 19.1±10.9 | 18.7±5.9 | 17.7±4.6 | 16.1±3.5 | 15.2±3.4 | 16.4±4.2 | 17.8±6.0 | 17.5±6.4 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.1±7.0 | 22.7±18.0 | 18.1±8.7 | 18.8±7.3 | 15.3±7.1 | 17.9±9.4 | 16.2±7.3 | 18.3±10.6 | 24.0±12.7 |

| CREATININE (mg/dL) | 0.8±0.2 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.3 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.7±0.1 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.1 |

| AED (number) | 1.0±0 | 2,59±0.7 | 1.0±0.0 | 2.8±0.9 | 3.2±0,6 | 2.7±0.7 | 3.4±0.5 | 2.0±1.1 | - |

| AO (year) | 17.8±12.2 | 12.2±10.7 | 19.3±13.6 | 13.7±9.5 | 14.5±16.0 | 13.3±14.0 | 4.9±3.6 | 15.7±12.1 | - |

| Groups | Maingroups | Subgroups | Total | Control group | |||||

| Value |

LTG-mono (N=16) |

LTG-poly (N=16) | OXC-mono (N=16) | OXC-poly (N=15) | Non LTG+OXC (N=10) |

ZNS (N=11) |

LCM (N=8) |

Total patients (N=75) | Control (N=13) |

| BDNF1 (ng/mL) | 7.9±4.1 | 7.9±2.8 | 8.6±4.1 | 8.0±2.7 | 9.5±3.6 | 6.7±2.2 | 9.7±3.6 | 8.3±3.5 | 6.7±3.4 |

| Correlations¥ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TDM LTG (µg/mL) | n.s | n.s. | - | - | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | - |

| TDM OXC 2 (µg/mL) | - | - | rho=-0.515, p=0.041 | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TDM ZNS (µg/mL) | - | rho=-0.829, p=0.042 | - | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | - |

| TDM LCM (µg/mL) | - | - | - | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TDM CBZ (µg/mL) | - | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TDM CBZ-E (µg/mL) | - | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TDM PRM (µg/mL) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | n.s. | - |

| LTG(mg) | n.s | n.s. | - | - | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | - |

| OXC (mg) | - | - | n.s. | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| ZNS (mg) | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | - | rho=-0.647, p=0.031 | - | n.s. | - |

| LCM (mg) | - | - | - | n.s. | rho=-0.850, p=0.015 | - | rho=-0.741, p=0.036 | rho=-0.714, p=0.006 | - |

| CBZ (mg) | - | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| VPA (mg) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | n.s. | - |

| LEV (mg) | - | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TPM (mg) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | n.s. | - |

1Data are expressed as means ± SD. WBC; White Blood Cells, PLT; Platelet, AST; Aspartate Aminotransferase, ALT; Alanine Aminotransferase, AED; The number of antiepileptic drug, AO; The age of onset of the patients, BDNF: Brain-derived neuroprophic factor, ¥BDNF levels and TDM values correlations for each groups. n.s.: not significant. 2This data is expressed as MHD (Mono Hydroxy Derivative of OXC) concentration. LTG; Lamotrigine OXC; Oxcarbazepine, ZNS; Zonisamide, LCM; Lacosamide, CBZ; Carbamazepine, CBZ-E; Carbamazepine epoxide, PRM; Primidone, LEV; Levetiracetam, VPA; Valproic acid, TPM; Topiramate.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants and BDNF correlation between these groups.

| GROUPS |

TOTAL PATIENTS*

(N=80) n (%) |

CONTROL GROUP* (N=13) n (%) | p1 value | p2 value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic value1 | ||||

| Gender (Female) | 45 (56.3) | 7 (53.8) | n.s. | n.s. |

| Education | - | - | ˂0.001# | χ2=10.4, 0.016€ |

| Primary and literate | 27 (33.75) | - | - | - |

| Middle School | 12 (15.0) | 1 (7.7) | - | - |

| High School | 28 (35.0) | 2 (15.4) | - | - |

| University | 12 (15.0) | 10 (76.9) | - | - |

| Marital status (Married) | 32 (40.0) | 9 (69.2) | χ2=3.876, 0.049 | n.s. |

| Economical situation (Medium) | 67 (84.6) | 13 (100.0) | n.s. | n.s. |

| Smokıng (Yes) | 12 (14.1) | 5 (38.5) | n.s. | n.s. |

| Clinical characteristics value1 | ||||

| Treatment (Polytherapy) | 46 (57.5) | - | n.s. | n.s. |

| Other drug use (Yes) | 44 (47.3) | - | n.s. | n.s. |

| Accompanying diseases (Yes) | 38 (40.9) | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Epilepsy type (Focal) | 58 (72.5) | - | n.s. | t=2.538, 0.013 |

| Etiology | - | - | n.s | n.s |

| Genetic | 18 (22.5) | - | - | - |

| Structural/Metabolic | 38 (47.5) | - | - | - |

| Unknown cause | 24 (30.0) | - | - | - |

| Syndromes | - | - | n.s | n.s |

| Unknown cause | 23 (28.2) | - | - | - |

| Perinatal Trauma | 10 (12.8) | - | - | - |

| Trauma | 6 (7.7) | - | - | - |

| Infection | 2 (2.6) | - | - | - |

| Tumor | 5 (6.4) | - | - | - |

| MCD (Hemimegalencephaly etc.) | 5 (6.4) | - | - | - |

| MTLE | 13 (15.4) | - | - | - |

| Reflex Epilepsies | 1 (1.3) | - | - | - |

| EWGTCSA | 3 (3.8) | - | - | - |

| JME | 7 (9.0) | - | - | - |

| JAE | 2 (2.6) | - | - | - |

| LKS | 1 (1.3) | - | - | - |

| BECTS | 1 (1.3) | - | - | - |

| CAE | 1 (1.3) | - | - | - |

| Number of seizure | - | - | n.s | n.s |

| Less than 1 year | 30 (37.5) | - | - | - |

| More than a month | 28 (35.0) | - | - | - |

| 1 month - 1 year | 22 (27.5) | - | - | - |

1Significant value of total with control group for socio-demographic and compoatiion between variable groups e.g. focal/generalize for clinical characteristic in the maingroups and in the subgroups. 2Comparation between variable groups e.g. female/male for BDNF values. *Data are expressed as a percentage. # Freeman Halton Test. € Kruskall Wallis test, the highest is primary and literate also the others. M; Medium, MCD; Malformations of cortical development, MTLE; Mesial Temporal Lope Epilepsy, EWGTCSA; Epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures alone, JME; Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, JAE; Juvenile absence epilepsy, LKS; Landau-Klefiner syndrome, BECTS; Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, CAE; Childhood absence epilepsy. Without impairment of consciousness or awareness; WOMAC; With observable motor or automatic components. WICA; With impairment of consciousness or awareness, EBCS;Evolving to a bilateral, convulsive seizure, GSTC; Generalized Seizures Tonic Clonic, BDNF; brain-derived neurotropic factor, n.s.: not significant.

3.2. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) and Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)

All patients underwent (42.5% monotherapy, 57.5% polytherapy) treatment. Overall, 69.5% LTG, 66.8% OXC, 70.7% ZNS, 84.7% LCM, 58.3% CBZ (66.6% CBZ-E), 33.3% VPA, 100.0% PB levels were in the therapeutic range (Table 3) in total patients.

Table 3.

The drug and therapeutic level information of the total patients.

| AED | Dose1 (mg/day) (n) |

TDM1

(µg/mL) (n) |

TDM Range

(µg/mL) |

Subtherapeutic2

n (%) |

Therapeutic2

n (%) |

Toxic2

n (%) |

Time I2

(year) n (%) |

Time II2

(year) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTG | 233.3±130.3 (36) | 4.5±2.5 (36) | 3-14 | 11 (30.6) ¶ | 25 (69.4) ¶ | - | 31 (86.1) | 16 (44.4) |

| OXC 3 | 1018.8±528.6 (36) | 16,7±9,8* (36) | 10-35 | 11 (30.6)¥ | 24 (66.7) ¥ | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 14 (38.9) |

| ZNS (n) | 288.2±85.8 (17) | 13.4±6.0 (17) | 10-40 | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | - | 13 (76.5) | 6 (35.3) |

| LCM (n) | 311.5±65.0 (13) | 7.1±3.3 (13) | 1-10 | - | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (30.8) | 13 (100.0) |

| CBZ (n) | 1108.3±274.6 (12) | 11.7±2.5 (12) | 4-12 | - | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 12 (100.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| CBZ-E | - | 2.8±0.8 (12) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PB (n) | 100.0±0.0 (1) | 21.7±8.4 (3) | 10-40 | - | 3 (100.0) | - | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| PRM (n) | 562.5±88.4 (2) | 11.2±6.2 (3) | 5-10 | 1 (33.3) | - | 2 (66.7) | 2 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| VPA (n) | 1625.0±629.2 (4) | 68.5±54.9 (3) | 40-100 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (100.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| LEV (n) | 2328.1±679.3 (32) | - | 10-40 | - | - | - | 28 (87.5) | 17 (53.1) |

| TPM (n) | 218.8±134.4 (4) | - | 5-20 | - | - | - | 3 (75.0) | 4 (100.0) |

| GBP (n) | 1600.0±0.0 (1) | - | 2-20 | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| PGB (n) | 75.0±0.0 (1) | - | 2.8-8.3 | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| CLB (n) | 20.0±0.0 (1) | - | 30-300 | - | - | - | 1 (100.0) | - |

1Data are expressed as means ± SD (n). 2Data are expressed as a percentage. Time I; Exposure to the drug and data are expressed as using AED more than year. Time II; Exposure to the current doses and data are expressed as using less than year of this dose (actual doses). 3This data is expressed as MHD (Mono Hydroxy Derivative of OXC) concentration. ¶ Fisher exact test was used for analysing of drug using time for LTG between TDM-LTG subtherapeutic and therapeutic (p=0,023). Subtherapeutic (n=11); 4/7, therapeutic (n=25); 1/24 for crosstab, time groups were more 1 year and less 1 year. ¥Freeman halton test was used for analysing for seizure frequence between TDM-MHD subtherapeutic and therapeutic (p=0,022). Subtherapeutic (n=11); 10/1/0, therapeutic (n=24); 10/9/5 for crosstab, seizure frequency groups were 0-1 month/1 month-1 year/more 1 year- LTG; Lamotrigine OXC; Oxcarbazepine, ZNS; Zonisamide, LCM; Lacosamide, CBZ; Carbamazepine, CBZ-E; Carbamazepine epoxide, PB; Phenobarbital, PRM; Primidone, VPA; Valproic acid, LEV; Levetiracetam, TPM; Topiramate, GBP; Gabapentin, PGB; Pregabalin, CLB; Clobazam.

Eighty-eight participants’ BDNF levels were measured (Table 1) and there were no significant differences between BDNF levels of all patients (t=1.611, p=0.111), the maingroups (F=0.858, p=0.54), and the subgroups (F=3.083, p=0.061) compared with control group. There were differences between BDNF levels and some characteristics as shown in Table 2. Moreover, BDNF levels were higher in focal epilepsy group and in those with higher education level. There was a negative correlation between BDNF levels and PLT value (r =-0.680, p=0.021) in OXC-poly group, ALT value (rho=-0.731, p=0.04) in ZNS-group (Tables 1, 2).

The value of the timing of exposure to the drug is summarized in Table 3. Accordingly, TDM-LTG (serum lamotrigine levels) showed significant differences in those using LTG more than a year (p=0.023) and seizure frequency (Fisher, p=0.022) (Table 3).

3.3. Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE-31)

Seventy-nine patients were assessed by the QOLIE-31. OS was over 50 in 88.6% of the patients. The test scores of various groups are summarized in Table 4. There were significant differences between OS (p<0.001), T-total score (p=0.001) of the maingroups. There were differences between TSW (p=0.003), TC (p=<0.001), TSF (p=0.001) of the subgroups. There were no correlations between OS (p=0,848), and no significant differences OS (<50 and ≥ 50) (p=0.921) with BDNF levels.

Table 4.

QOLIE-31 test scores of the study patients.

| MAINGROUPS1 SUBGROUPS2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOLIE-31 | Number of Items | Range¶ (min-max) |

LTG-Mono

(N= 17) |

LTG-poly

(N= 16) |

OXC-Mono

(N= 17) |

OXC-poly (N= 17) |

Non LTG+OXC

(N= 10) |

Test

statistics, p value |

ZNS

(N= 11) |

LCM

(N= 8) |

Test statistics,

p value |

| Seizure Worry (SW) ǂ | 5 | 0-100 | 62.6±25.3 | 70.1±24.0 | 73.7±22.7 | 74.0±19.2 | 38.0±34.6 | F=4.286, |0.004 | 64.6±31.4 | 57.9±25.2 | n.s. |

| Overall Quality of Life (OQOL)ǂ | 2 | 25-95 | 66.9±12.1 | 63.1±16.3 | 70.9±16.8 | 63.7±19.3 | 52.0±13.1 | n.s. | 58.4±21.1 | 54.4±13.9 | n.s. |

| Emotional Well-Being (EWB) | 5 | 10-100 | 70.8±18.9 | 69.3±16.5 | 74.4±18.4 | 68.9±13.3 | 56.8±20.5 | n.s. | 64.7 ±18.3 | 63.0±17.6 | n.s. |

| Energy/Fatigue (EF)ǂ | 4 | 10-100 | 58.5±25.8 | 58.4±17.8 | 59.1±24.6 | 63.5±19.4 | 48.5±21.5 | n.s. | 60.9±18.1 | 59.4±24.6 | n.s. |

| Cognitive (C) | 6 | 13.3-100 | 55.5±24.4 | 82.7±16.9 | 78.1±14.5 | 79.9±14.4 | 51.6±23.8 | χ2=23.177, <0.001 | 72.4±23.6 | 79.7±13.3 | n.s. |

| Medication Effects (ME) | 3 | 100-100 | 70.1±34.4 | 62.0±25.6 | 77.0±24.4 | 75.7±19.5 | 51.7±28.5 | n.s. | 62.6±24.5 | 66.3±22.9 | n.s. |

| Social Function (SF) | 5 | 10-100 | 83.3±18.6 | 73.1±25.4 | 90.6±15.5 | 76.8±22.5 | 50.5±20.7 | χ2=20.052, <0.001 | 59.8±26.3 | 61.8±21.9 | n.s. |

| Overall Score (OS)ǂ | 30 | 19.3-96.9 | 66.6±15.2 | 71.4±8.9 | 76.5±14.5 | 72.8±11.1 | 50.8±17.1 | F=6.614, <0.001 | 64.4±13.8 | 65.3±10.4 | n.s. |

| 31rd question (total health status) | e | 0-100 | 76.5±20.9 | 63.8±25.5 | 73.5±17.7 | 62.9±23.7 | 49.0±24.7 | χ2=10.9, 0.027 |

51.8±29.9 | 60.0±18.5 | n.s. |

ǂANOVA test was applied for statistical analysis. ¶Data are expressed as minimum-maximum. QOLIE-31, The 31-item Quality of life in Epilepsy, data are expressed as means ± SD. LTG; Lamotrigine OXC; Oxcarbazepine, ZNS; Zonisamide, LCM; Lacosamide.

Regarding total health status (31st question), there were significant corelations between Non LTG+OXC and LTG-mono (p=0.039) in the maingroups (p=0.027) (Table 4). There were positive correlations between OS and total health status of LTG-mono (rho=0.600, p=0,011), LTG-poly (rho=0,56, p=0.026), OXC-poly (rho=0.550, p=0.023), Non LTG+OXC (rho=0.650, p=0.040) in the maingroups and in total (rho=0.550, p˂0.001).

There were negative corelations between BDNF levels and OQoL (r=-0.536, p=0.032), and TOQoL (r=-0.516, p=0.041) of LTG-poly. Positive correlations were observed between BDNF levels and EWB (rho=0.773, p˂0.001), and TEWB score (rho=0.773, p˂0.001) of OXC-poly.

3.4. Efficacy and Safety

The etiology, seizure frequency, other clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Therapeutic information is provided in Table 3. The groups of efficacy and safety are summarized in Figs. 1-3. According to the therapeutic intervals determined in TDM, therapeutic failure was observed in 41 of the patients. The findings of AED-AED interactions for ten and AED-OD interactions for eight patients showed therapeutic failure. These interactions were OXC-ZNS, CBZ-LTG, CBZ-ZNS, ZNS-CLB, and LEV-CBZ ve LTG-PB.

There were 92 unwanted side effects for OADs and 299 unwanted side effects for NADs. The mean of the unwanted side effect was 3.6±2,4. The most lower side effect was for OXC-mono group, the value was 2.35. Although the other 21 patients had no drug-interactions (Appendix e-1). OD interactions may also be caused by antihypertensives, vitamins, thyroid hormone preparations, oral contraceptives, NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), antibacterial agents and proton pump inhibitors.

The correlation of the values of therapeutic success and therapeutic failure groups for BDNF, QOLIE-31, and some unwanted effects are shown in Figs. 1-3. BDNF level was higher in the failure group (p=0.035). There were no correlations between BDNF levels and unwanted side effects (rho=0.151, p=0.161), but there was a significant difference in the number of unwanted side effects groups (0 - ≥6) with BDNF (χ2=23.378, p=0.001), EWB (F=4.528, p=0.001), C (χ2=18.622, p=0.05), SF (χ2=13.934, p=0.03), total health status (χ2 =22.356, p=0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

The absence of inter-group variability in the epileptic population ensured standardization and made this cross-sectional clinical study valuable. This study on NADs assessed the efficiency, safety, seizure frequency and concordant clinical features based on single/dual focal points, and also increased the success rate of pharmacologic treatment. On the other hand [19], patients with other CNS pathologies, especially MDD, were excluded from the study in order to reduce the risk of psychiatric comorbidity and to ensure a homogenous assessment of biomarkers of BDNF in patients suffering only from epilepsy.

4.1. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

Simultaneous fast monitoring of OADs and NADs provided an advantage, especially in polytherapies and guided clinician for patient management in this study. Although new advancements and strategies [20, 21] are developed for management of pharmacological/non-pharmacological treatments of epileptic patients, this study emphasizes the indispensability of TDM in a personalized treatment. With the significance of developing a single analysis system [22] for monitoring ODs and many molecules, this study confirms the need for future clinical studies on TDM. This study emphasizes the importance of TDM especially in Phase IV, observational studies on original and generic products (efficiency and new indication), and pharmacovigilance studies, surveillance systems for safety and shows the need for research in this field and the meticulous management of relevant controls in Turkey [23].

TDM is a very important indicator; however, it should be considered that it is not the only determinant in some cases. Although the same dose was administered during the treatment, between patients may have different serum levels. This is considered due to the pharmacokinetic characteristics of NADs [24-26] and increases the rate of unwanted effects. The most common unwanted effects were detected in this study. It also evaluated the TDM and AED-interactions and other variables as a whole [27]. Although the probability of CYP1A2-dependent mechanism of CBZ is known, examples of therapeutic failure were not observed in this study. Nevertheless, as in the case of poor inhibition of OXC due to alcohol, interaction due to stimulation of these enzymes and CYP2E1 was not detected in this study. For patients whose therapeutic failure cannot be explained by drug-interactions, the dose should be increased or decreased. Therefore, analyzing such patients individually would be more appropriate. In terms of seizure frequency, the subtherapeutic serum level of OXC was attributed to a good response for most of the participants and doses; whereas, for LTG, it was attributed to LTG exposure for less than a year.

When treatment was successful, BDNF was restored to Baseline [28] and when there was a good response to seizure, BDNF could be restored. The majority of patients with poor response to the therapeutic level were in the OXC-group and this suggests that LTG responds better to the treatment than OXC. OXC is less affected by other variables; thus, patients with poor response require additional treatment with NAD in order to avoid the risk of toxicity [29].

4.2. Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)

The efficiency of AEDs, such as CBZ, VPA and LTG, in depression is known [8, 13] and this study supports the relationship between BDNF and MDD [13, 19, 30] in accordance with the results of epileptic-nondepressed patients treated with AED. The result of a twenty-five percent increase in serum BDNF level is attributed to AED treatment, probably due to the antiglutamatergic effect [31]. In addition to the effects of BDNF similar to antidepressants, SSRI/NA treatment increases BDNF production and stimulates synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis via BDNF in VPA treatment [32, 33]. In this study, it was shown that AEDs have a slight contribution to the increase in BDNF via these mechanisms. Regarding the seizure and VPA effect, certain undefined pharmacokinetic effects of AEDs and focal/generalized BDNF difference can be attributed to mechanisms suggested by BDNF and PKC-epsilon activation and GABA (A) receptor-mediated responses [34].

LTG, with a well-known effect in major depression, had increased BDNF levels in our study, albeit without reaching statistical significance. On the other hand, another study suggested the lack of change from the basal values between MDB and BDNF may relate to the usage of different anti-depressant drugs in these patients. We suggest that the difference observed in our results may relate to the presence of depression and/or other drugs used. It was suggested also that the acute effect of LTG augmentation therapy in major depression is not associated with BDNF at least in refractory depression [35].

The lower serum level in LTG-monotherapy and better clinical progress in OXC-monotherapy suggest that BDNF and QoL interact mutually. In addition to clinical progress, polymorphism, QoL and BDNF can explain the deviations in population; however, pharmacogenetic testing with TDM can be useful [36].

With AED treatment, the overall condition of a patient can change depending on unwanted effects, overdose and tolerance; epilepsy may be triggered and inverse pharmacodynamic effects may emerge. As in relationship with increased AED number [37], the cause behind the negative correlation between TDM and BDNF in polytherapies can be associated with this condition. High BDNF level in AED treatment with efficient, safe and appropriate dose and low level of BDNF in the reverse and resistant cases are mostly concordant with a clinical picture of the patient. As in ZNS-group, increased dose and serum level in patients with poor prognosis or inefficient AED treatment may negatively affect BDNF. A low dose of OXC in OXC-monotherapy group with good prognosis explains the TDM-MHD findings. This study reveals the relationship between the adverse effects, such as reversible negative effects of dose on PHT, and development of toxic level treatment-related ataxia [38] and pathophysiology and the examples. While the toxic level of BDNF can decrease via unwanted effects due to increased dose; this can lead to increased levels of BDNF despite the poor prognosis (LCM-group). However, it can also promote tolerance and inverse pharmacodynamic effect similar to TDM-LCM. In pharmacoresistant cases, administration of a high dose is required to reach efficient levels in the blood as in rapid metabolizers and BDNF is a positive feedback to the neuron before synapse [32]. A similar result was detected in this study, and BDNF is proposed as a therapeutic target for epileptic patients [39].

How BDNF can decrease the levels of TDM-ZNS and TDM-MHD and how high dose AEDs can reduce levels of BDNF as in ZNS-dose and LCM-dose suggest neurotoxicity risk and/or the reduction of BDNF’s neuroprotective effects [37, 40]. Considering the unknown mechanism of BDNF, increased levels of MHD independent of the number of AED and decreased levels of BDNF in OXC-monotherapy suggest that increasing dose in this group with a good response can negatively affect BDNF.

With the minimum AED dose required to control seizure, decreased duration of AED exposure and number of AEDs can improve BDNF levels. If the new additional treatment cannot provide seizure control, the level of BDNF cannot improve. In other words, increased dose and level in additional treatments, such as ZNS and LCM to increase the response to treatment, reduce BDNF levels.

4.3. Evaluation of Safety

This study showed the negative effects of AED on TDM and QoL and the effects were evaluated with seizure frequency. A limited number of AED-AED interactions were mostly detected in LTG-polytherapy, and it is similar to the changes in primary AED concentrations [41]. Although OXC-monotherapy carries the highest risk in AED-OD, the levels of MHD were not significantly affected. Although enzyme levels cannot be monitored, the interaction between OXC and ZNS, CBZ and ZNS and LTG explains the subtherapeutic levels with CYP3A4 metabolism. Regarding the concentration [42], AED-AED interaction was not observed in the first degree; however, rare cases of second degree were observed. Within the third degree, since LTG/OXC may reduce the efficiency of ODs by decreasing their levels, it was regarded as the most commonly observed unwanted effect [43]. Scans can be performed to reduce side effects [44], and new additional treatment or dose adjustment strategies should be established. Studies conducted on TDM and safety test applications will determine the risk distribution in the Turkish population in comparison with other countries. Participation in country-based distribution programs by the World Health Organization (WHO) can increase the success in treatment and contribute to developing safer new molecules.

Unlike the decrease in BDNF due to interaction with PB [45], high BDNF level indicates the positive outcome of AED treatment. This explains the negative effect of interaction on health status, seizure and clinical progress. However, avoiding interactions reduces risks and this study shows that SF is better at monotherapies. Cognitive unwanted effects can reduce the correlation between QoL and BDNF, increase cellular neogenesis and different AEDs can lead to different cognitive disorders [46]. This may be explained by different mechanisms, such as the repressive effect of LCM on learning and memory via BDNF/TrkB inhibition [47], however, ZNS may affect BDNF by unwanted effects rather than hepatotoxicity [18, 23, 48]. The outcome may be due to drugs, such as CBZ and VPA, that elevate ALT. PLT increase in OXC-polytherapy is not concordant with BDNF reduction [49].

4.4. Quality of Life (QoL)

Prescribed NAD treatment increases the QoL and leads to a very positive clinical picture. The majority of the participants answered questions easily, the treatment was performed on patients who did not require emergency intervention and patients were followed-up effectively by the physician and they comply with the treatment and these are considered as criteria for high QoL. For epileptic patients, in addition to treatment with high-efficient, non-toxic AEDs within the therapeutic range, it is recommended that psychoneuropharmacologic approach should be adopted due to emotional wellness and cognitive change, anxiety, depression and social isolation [1, 17]. It is considered that this will have a positive effect on QoL.

Awareness training/meetings will be more effective due to their psycho-social effects since epileptic patients have poor educational background and marriage rates.

Differences in QoL are attributed to the superiority of drug groups. This study showed that prescribed treatment and monotherapies are associated with better quality of life [50]. The fact that OXC-monotherapy is the best EWB and the highest rate of SW in resistant cases is in Non-LTG+OXC group indicates the concordance of this study with the clinical findings. Moreover, SW reduces energy in the resistant group. Fatigue is the second most frequent side effect in all groups and it is similar to EF and this proves the results. High monotherapies in QoL, SF and ME are attributed to the fact that drugs are less effective under risk, such as drug interaction, and unwanted effects. Low AED-AED interaction proves the negative effect of drug-interactions on QoL. Unwanted effects, such as “forgetfulness”, in the majority of patients indicate negative effects on QoL, health status and cognition. The use of LTG and OXC in treatment can give a better clinical picture in terms of safety and QoL, and the use of LTG and OXC separately in combination with other AEDs without any drug-interaction risk can improve unwanted effects, increasing the QoL compared with monotherapies. LTG has a more negative effect on cognition [48], whereas ZNS has a less negative effect. ZNS and LCM are not superior to each other in terms of QoL. The more the QoL increases, the more their health status improve. Improved health status indicates a positive effect of given treatment by the physician.

Poor health status in polytherapy at toxic levels suggests selective use of TDM in epilepsy treatment and obtaining the levels as a response to the pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic problems will decrease the unwanted effects to a minimum [51]. In this study, those with therapeutic success had a better QoL, social functions, and cognition. In terms of success in TDM, OXC has a higher positive effect on cognition than OD groups. When efficient and safe treatment is achieved with therapeutic success, the quality of life and condition of the patient will be improved.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the therapeutic range of each drug was assessed in high risk and/or resistant patients. The superiority of NADs was revealed, choosing rational and personalized AED was facilitated, and practice integrity was achieved with close collaboration of clinical pharmacology with clinicians. Positive findings in QoL were attributed to the success of the given treatment by the clinician. The NAD treatment indicates that long-term safety studies, assessment of the QoL, psycho-social effects and multi-treatment approach are required. This study is an important indicator of the close relationship between dose-level-seizure activities. The correct relationship between them is positively reflected in BDNF and QoL. The connection between BDNF and dose and level suggests that there is a positive contribution with the neuroprotective effect of BDNF for the prevention of depression in epilepsies. It is suggested that BDNF is a new therapeutic target in anti-epileptogenic and anti-depressant therapy and contributes to the development of a candidate new drug molecule and personalized treatment options.

Fig. (2).

Safety evaluation and comparison for unwanted effects. A; All participants were divided into there groups: A1) cognition unwanted effect owner, A2) cognition unwanted effect not owner, A3) control group. B; All participants were divided into there groups: B1) forgetfulness unwanted effect owner, B2) forgetfulness unwanted effect not owner, B3) control group. C; All participants were divided into there groups: C1) learning difficulty unwanted effect owner, C2) learning difficulty unwanted effect not owner, C3) control group. Control group was added to the each binary and quaternary groups for only BDNF comparisons and user ANOVA test. AED; Antiepileptic Drug NAD; New Antiepileptic Drug, OAD; Old Antiepileptic Drug, OD; Other Drug, Mono; Monotherapy, Poly; Polytherapy, BDNF; Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, SW; Seizure Worry, OQOL; Overall Quality of Life, EWB; Emotional Well-Being, EF; Energy/Fatigue, C; Cognitive, ME; Medication Effects, SF; Social function, OS; Overall score.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the neurology academicians specialists, assistants. secretary of the epilepsy polyclinic Mr Ender Bostancı and nurses. Thank you for contributions in BDNF analysis to M,Sc,, PhD (c) Faruk Çelik. Thank you for technical supports to Redoks and Medsantek firms to personals. Associate Professor Asuman Gedikbaşı and Prof. Dr. Ümit Zeybek thanks for permission granting the laboratories.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AEDs

Antiepileptic Drugs

- BDNF

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor

- BECTS

Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes

- C

Cognitive

- CAE

Childhood Absence Epilepsy

- CBZ

Carbamazepine

- CBZ-E

Carbamazepine-10, 11-Epoxide

- CLB

Clobazam

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- EBCS

Evolving to A Bilateral Convulsive Seizure

- EF

Energy/Fatigue

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- EWB

Emotional Well-Being

- EWGTCSA

Epilepsy With Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures Alone

- GBP

Gabapentin

- GSTC

Generalized Seizures Tonic Clonic

- HPLC

High Pressure Liquid Chromatography

- JAE

Juvenile Absence Epilepsy

- JME

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

- LCM

Lacosamide

- LEV

Levetiracetam

- LKS

Landau-Klefiner Syndrome

- LTG

Lamotrigine

- M

Medium

- MCD

Malformations of Cortical Development

- MCI

Mild Cognitive Impairment

- MDD

Major Depression Disorders

- ME

Medication Effects

- MHD

10-Monohydroxy Derivative of Oxcarbazepine

- Mono

Monotherapy

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

- MTLE

Mesial Temporal Lope Epilepsy

- NADs

New Antiepileptic Drugs

- NSAIDs

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- OADs

Old Antiepileptic Drugs

- OD

Other Drugs

- OQOL

Overall Quality of Life

- OS

Overall Score

- OXC

Oxcarbazepine

- PB

Phenobarbital

- PGB

Pregabalin

- Poly

Polytherapy

- PRM

Primidone

- QoL

Quality of Life

- QOLIE-31

Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory

- SF

Social function

- SW

Seizure Worry

- TDM

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

- TDM-CBZ

Serum Carbamazepine Levels

- TDM-CBZ-E

Serum Carbamazepine-10,11-Epoxide Levels

- TDM-LCM

Serum Lacosamide Levels

- TDM-LTG

Serum Lamotrigine Levels

- TDM-OXC

Serum Oxcarbazepine Levels

- TDM-PRM

Serum Primidone Levels

- TDM-ZNS

Serum Zonisamide Levels

- TPM

Topiramate

- VPA

Valproic acid

- WICA

With impairment of Consciousness or Awareness

- WOMAC

With Observable Motor or Automatic Components

- ZNS

Zonisamide

KEY POINTS

● BDNF levels were higher in the focal epilepsy group and in patients using oxcarbazepine monotherapy among the investigated NADs.

● Increased dose and levels of NADs associated with poor prognosis/inefficient treatment may negatively affect BDNF levels.

● Prescribed NAD treatments seemed to increase the quality of life since 88.6% of the patients showed satisfactory scores.

LIMITATIONS

This study is a doctorate thesis project of Meral Demir. As the doctorate project has standard funding, these financial constraints limited the size of the sample.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the İstanbul Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ethical approval Number: 39, Turkey).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this study. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (http://www.wma.net/en/20activities/10ethics/10helsinki/)

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

An informed consent was obtained from the volunteers. The volunteers were informed of the purpose of the study. All volunteers. Signed informed consent before any study-related procedures were performed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

This present work was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Istanbul University (Project Number: 53417, ID: 2688).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Appendix e-1

AED-AED İnteraction of the patients with TDM.

|

REFERENCES

- 1.Azuma H., Akechi T. Effects of psychosocial functioning, depression, seizure frequency, and employment on quality of life in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patsalos P.N., Berry D.J., Bourgeois B.F., Cloyd J.C., Glauser T.A., Johannessen S.I., Leppik I.E., Tomson T., Perucca E. Antiepileptic drugs--best practice guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by the subcommission on therapeutic drug monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Destache C.J. Use of therapeutic drug monitoring in pharmacoeconomics. Ther. Drug Monit. 1993;15(6):608–610. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199312000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krasowski M.D., McMillin G.A. Advances in anti-epileptic drug testing. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2014;436:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sener A., Akkan A.G., Malaisse W.J. Standardized procedure for the assay and identification of hypoglycemic sulfonylureas in human plasma. Acta Diabetol. 1995;32(1):64–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00581049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannessen S.I., Tomson T. Pharmacokinetic variability of newer antiepileptic drugs: when is monitoring needed? Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(11):1061–1075. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645110-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gökyiğit A., Baykan-Kurt B., Karaağaç N., et al. Tedaviye dirençli epilepside ek tedavi olarak uygulanan lamotrigin ile 3 aylık, çok merkezli, etkinlik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Epilepsi. 1997;3:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollard J.R., Eidelman O., Mueller G.P., Dalgard C.L., Crino P.B., Anderson C.T., Brand E.J., Burakgazi E., Ivaturi S.K., Pollard H.B. The TARC/sICAM5 ratio in patient plasma is a candidate biomarker for drug resistant epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 2013;3(181):181. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalia M., Costa E Silva J., Silva J. Biomarkers of psychiatric diseases: current status and future prospects. Metabolism. 2015;64(3) Suppl. 1:S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russo-Neustadt A.A., Chen M.J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and antidepressant activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005;11(12):1495–1510. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagahara A.H., Tuszynski M.H. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10(3):209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong Z., Li W., Qu B., Zou X., Chen J., Sander J.W., Zhou D. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in epilepsy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014;21(1):57–64. doi: 10.1111/ene.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventriglia M., Zanardini R., Bonomini C., Zanetti O., Volpe D., Pasqualetti P., Gennarelli M., Bocchio-Chiavetto L. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in different neurological diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2013;2013:901082. doi: 10.1155/2013/901082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: Report of the ILAE commission on classification and terminology 2005-2009. Epilepsia. 2010;5:676–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ClinRep therapeutic drug monitoring. Access, 25.2.2015. HPLC complete kits (web page on the internet). www.recipe.de/en/products_hplc.htlm

- 16.Vickrey B.G., Perrine K.R., Hays R.D., et al. Access, 13.3.2015. Quality of life in epilepsy QOLIE-31 Version 1.0 Scoring Manual (web page on the internet). www.rand.org

- 17.Mollaoğlu M., Durna Z., Bolayir E. Validity and reliability of the quality of life in epilepsy inventory (QOLIE-31) for Turkey. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2015;52(3):289–295. doi: 10.5152/npa.2015.8727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Access, 18.2.2015. Truven Health Analytics Micromedex Solutions Veritabanı (web page on the internet). http: //www.micromedexsolutions. com/micromedex2/librarian/ (Accessed on 18 February 2015).

- 19.Shimizu E., Hashimoto K., Okamura N., Koike K., Komatsu N., Kumakiri C., Nakazato M., Watanabe H., Shinoda N., Okada S., Iyo M. Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Veenendaal T.M., IJff D.M., Aldenkamp A.P., Lazeron R.H.C., Hofman P.A.M., de Louw A.J.A., Backes W.H., Jansen J.F.A. Chronic antiepileptic drug use and functional network efficiency: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. World J. Radiol. 2017;9(6):287–294. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v9.i6.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennewitz M.F., Saltzman W.M. Nanotechnology for delivery of drugs to the brain for epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faught E., Szaflarski J.P., Richman J., Funkhouser E., Martin R.C., Piper K., Dai C., Juarez L., Pisu M. Risk of pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic and other drugs in older persons and factors associated with risk. Epilepsia. 2018;59(3):715–723. doi: 10.1111/epi.14010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(web page on the internet). Turkish Medicines and Medical Devices Agency. Short Product Information. www.titck.gov.tr (Accessed on 18 February 2015).

- 24.Kayaalp O. Akılcı Tedavi yönünden Tıbbi Farmakoloji Kitabı 13nd. Ankara: Pelikan Yayıncılık; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marson A.G., Kadir Z.A., Hutton J.L., Chadwick D.W. The new antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of their efficacy and tolerability. Epilepsia. 1997;38(8):859–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallelli L., Palleria C., De Vuono A., Mumoli L., Vasapollo P., Piro B., Russo E. Safety and efficacy of generic drugs with respect to brand formulation. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013;4(Suppl. 1):S110–S114. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.120972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenow F., van Alphen N., Becker A., Chiocchetti A., Deichmann R., Deller T., Freiman T., Freitag C.M., Gehrig J., Hermsen A.M., Jedlicka P., Kell C., Klein K.M., Knake S., Kullmann D.M., Liebner S., Norwood B.A., Omigie D., Plate K., Reif A., Reif P.S., Reiss Y., Roeper J., Ronellenfitsch M.W., Schorge S., Schratt G., Schwarzacher S.W., Steinbach J.P., Strzelczyk A., Triesch J., Wagner M., Walker M.C., von Wegner F., Bauer S. Personalized translational epilepsy research - Novel approaches and future perspectives: Part I: Clinical and network analysis approaches. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;76:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Almeida A.A., Gomes da Silva S., Lopim G.M., Vannucci Campos D., Fernandes J., Cabral F.R., Arida R.M. Resistance exercise reduces seizure occurrence, attenuates memory deficits and restores BDNF signaling in rats with chronic epilepsy. Neurochem. Res. 2017;42(4):1230–1239. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouvel-Tallec A. [New antiepileptic drugs]. Rev. Med. Interne. 2009;30(4):335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaFrance W.C., Jr, Leaver K., Stopa E.G., Papandonatos G.D., Blum A.S. Decreased serum BDNF levels in patients with epileptic and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2010;75(14):1285–1291. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f612bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abelaira H.M., Réus G.Z., Ribeiro K.F., Zappellini G., Ferreira G.K., Gomes L.M., Carvalho-Silva M., Luciano T.F., Marques S.O., Streck E.L., Souza C.T., Quevedo J. Effects of acute and chronic treatment elicited by lamotrigine on behavior, energy metabolism, neurotrophins and signaling cascades in rats. Neurochem. Int. 2011;59(8):1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arıcıoğlu F. Psikiyatride farmakorezistans. Klinik Psikofarmakol. Bülteni. 2009;19(Suppl. 11):S43–S53. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kırlı S. Antidepresanların etki düzeneklerindeki benzerlik ve farklılıklar. Klinik Psikofarmakol. Bülteni. 2009;19(Suppl. 1):S86–S89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toth M. The epsilon theory: a novel synthesis of the underlying molecular and electrophysiological mechanisms of primary generalized epilepsy and the possible mechanism of action of valproate. Med. Hypotheses. 2005;64(2):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kagawa S., Mihara K., Suzuki T., Nagai G., Nakamura A., Nemoto K., Kondo T. Both serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and interleukin-6 levels are not associated with therapeutic response to lamotrigine augmentation therapy in treatment-resistant depressive Disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2017;75(3):145–150. doi: 10.1159/000484665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith R.L., Haslemo T., Refsum H., Molden E. Impact of age, gender and CYP2C9/2C19 genotypes on dose-adjusted steady-state serum concentrations of valproic acid-a large-scale study based on naturalistic therapeutic drug monitoring data. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;72(9):1099–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genton P. When antiepileptic drugs aggravate epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2000;22(2):75–80. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(99)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moon H.J., Jeon B. Can therapeutic-range chronic phenytoin administration cause cerebellar ataxia? J. Epilepsy Res. 2017;7(1):21–24. doi: 10.14581/jer.17004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen N.C., Chuang Y.C., Huang C.W., Lui C.C., Lee C.C., Hsu S.W., Lin P.H., Lu Y.T., Chang Y.T., Hsu C.W., Chang C.C. Interictal serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor level reflects white matter integrity, epilepsy severity, and cognitive dysfunction in chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;59:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glien M., Brandt C., Potschka H., Löscher W. Effects of the novel antiepileptic drug levetiracetam on spontaneous recurrent seizures in the rat pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43(4):350–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.18101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Dijkman S.C., Rauwé W.M., Danhof M., Della Pasqua O. Pharmacokinetic interactions and dosing rationale for antiepileptic drugs in adults and children. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;84(1):97–111. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johannessen S.I., Landmark C.J. Antiepileptic drug interactions - principles and clinical implications. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2010;8(3):254–267. doi: 10.2174/157015910792246254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.French J.A., Gazzola D.M. New generation antiepileptic drugs: what do they offer in terms of improved tolerability and safety? Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2011;2(4):141–158. doi: 10.1177/2042098611411127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egunsola O., Choonara I., Sammons H.M., Whitehouse W.P. Safety of antiepileptic drugs in children and young people: A prospective cohort study. Seizure. 2018;56:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Endesfelder S., Weichelt U., Schiller C., Winter K., von Haefen C., Bührer C. Caffeine protects against anticonvulsant-induced impaired neurogenesis in the developing rat brain. Neurotox. Res. 2018;34(2):173–187. doi: 10.1007/s12640-018-9872-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi X.Y., Wang J.W., Cui H., Li B.M., Lei G.F., Sun R.P. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on mRNA levels of BDNF and NT-3 and cell neogenesis in the developing rat brain. Brain Dev. 2010;32(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shishmanova-Doseva M., Peychev L., Koeva Y., Terzieva D., Georgieva K., Peychev Z. Chronic treatment with the new anticonvulsant drug lacosamide impairs learning and memory processes in rats: A possible role of BDNF/TrkB ligand receptor system. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2018;169:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Javed A., Cohen B., Detyniecki K., Hirsch L.J., Legge A., Chen B., Bazil C., Kato K., Buchsbaum R., Choi H. Rates and predictors of patient-reported cognitive side effects of antiepileptic drugs: An extended follow-up. Seizure. 2015;29:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burnouf T., Kuo Y.P., Blum D., Burnouf S., Su C.Y. Human platelet concentrates: a source of solvent/detergent-treated highly enriched brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Transfusion. 2012;52(8):1721–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haag A., Strzelczyk A., Bauer S., Kühne S., Hamer H.M., Rosenow F. Quality of life and employment status are correlated with antiepileptic monotherapy versus polytherapy and not with use of “newer” versus “classic” drugs: results of the “Compliant 2006” survey in 907 patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19(4):618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glauser T.A., Pippenger C.E. Controversies in blood-level monitoring: reexamining its role in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl. 8):S6–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb02950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study is the doctorate thesis project of Meral Demir. Baseline data are online (https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/tezSorguSonucYeni.jsp), and follow-up data are available to qualified investigators on request to the corresponding author.

Not applicable.