Letter to the editor

We read with interest the recent Gut article by Lemoinne et al describing a dysbiosis of the fungal gut community in faeces of patients suffering from primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).1 Though several reports, including our own previous data, support a functional and potentially pathogenic link between the intestinal bacteriota and liver inflammation in PSC,2 3 the aetiology of the disease remains largely unknown.

We here report on the fungal mycobiome results of our cohort from Northern Germany approved by the local ethics committees (A148/14 and MC-111/15) comprising stool samples of 66 healthy control (HC) subjects, 65 patients with well-characterised PSC (including a subgroup with concomitant colitis (PSC-IBD), n=32) and 38 subjects with UC.3 PCR and sequencing of the fungus-specific internal transcribed spacer 2 genomic region was performed as previously described4 using the primer pair 5.8S-Fun and ITS4-Fun on an Illumina MiSeq machine. Sequencing data were subjected to quality control by using the open source package DADA2 (V.1.10)5 in R (V.3.5.1; https://github.com/mruehlemann/ikmb_amplicon_processing). Amplicon sequence variants were taxonomically annotated using the UNITE ITS database (V.7.2).6

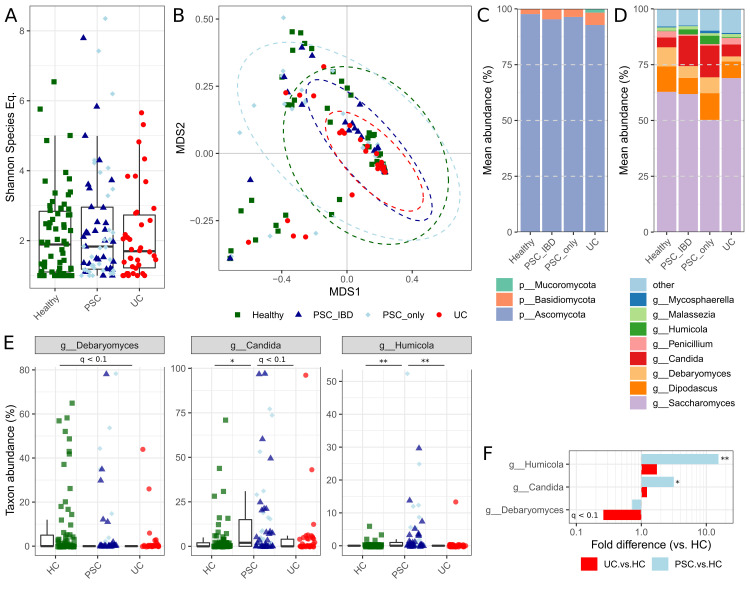

In disagreement with the findings in the French cohort,1 overall fungal alpha diversity in the German cohort was neither altered in PSC nor in UC versus HC as calculated by Shannon species equivalent (figure 1A). None of the disease groups significantly deviated in community composition from healthy individuals (all padonis >0.05; figure 1B). Fungal composition on phylum level was found to be mainly dominated by Ascomycota (figure 1C), particularly by the genera Saccharomyces, Candida and Dipodascus (figure 1D) in relatively higher abundance of reads when compared with the findings of Lemoinne et al.1 Though our results generally validate the previously described overall fungal composition in stool, we were not able to detect the genus Exophiala, which was found in five PSC patients from France exclusively. Whether this is due to methodological differences (choice of primer sets, data analysis tools and sampling depth) or presence of this fungus in only a subset of PSC patients not sampled in the German cohort needs to be determined.

Figure 1.

Mycobiome of individuals with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and UC as well as healthy controls (HC) (all of northern German origin). Rarefaction curves for Shannon diversity of sequence variants reached plateau between 50 and 100 sequences per samples, thus samples were normalised to 100 random reads per sample. (A) Alpha diversity as presented by Shannon species equivalents (all p>0.05). (B) Beta diversity ordination of the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity based on genus-level fungal abundances (all padonis >0.05). (C) Phylum-level and (D) genus-level mean abundances of all taxa with >1% mean abundance and present in at least 10 samples. (E) Group-wise box-and-whisker plots for significant genus level annotations tested for differential abundances with individual values represented as data points. (F) Differences in group-mean abundances of patients with PSC and UC, as compared with HC. *q<0.05, **q<0.01.

Disease-associated differential abundance of fungal taxa was investigated by applying Student’s t-test to the arcsin-squareroot-transformed relative abundances of all genera with mean abundance >1% and present in at least 10 individuals. This analysis revealed increased levels of the genera Candida and Humicola (species level annotation suggests H. grisea) in PSC patients with and without concomitant colitis compared with HC (all qBH <0.05; figure 1E and F) and UC (all qBH <0.1; figure 1E) individuals. H. grisea, recently reclassified as Trichocladium griseum,7 belongs to the fungal class Sordariomycetes, thus our results reproduce the significant increase of this class in PSC patients, as previously described by Lemoinne and colleagues, but at increased taxonomic resolution. Previous research on T. griseum showed that it is most frequently isolated from soil and plants but also occasionally found in patients suffering from peritonitis.8 In addition, the validated increase of Candida species in PSC patients argues for an immunogenic role of these fungi, particularly with respect to earlier findings that demonstrated their high potential to induce Th17 response in T cells.9 Increased Th17 numbers have previously been reported in PSC patients and recently been shown to be involved in PSC pathogenesis.10

In summary, both the significant increase of the fungal class Sordariomycetes, likely T. griseum, as well as of Candida species in stool samples of PSC patients, now found in two independent and geographically distinct PSC patient panels that were analysed with divergent methodological approaches, strongly demands for additional analyses on these fungi and their role in PSC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Ilona Urbach, Ms Ines Wulf and Mr Tonio Hauptmann of the IKMB microbiome laboratory for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @mruehlemann, @hov_jer

AF and CB contributed equally.

Contributors: AF and CB designed the study. CS and AF obtained funding. RZ, CS and WL acquired and quality-controlled patient samples and data. CB and MELS supervised sample processing and sequencing. MCR performed statistical analyses. MCR, MELS, RZ, TL, MK, JRH, CS, AF and CB interpreted data and drafted the manuscript with input and critical revision from all authors. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Clinical Research Group 306‚ Primary sclerosing cholangitis’ (no: KFO306) as well as Research Training Group 1743 and received infrastructure support from the DFG Cluster of Excellence ‘Inflammation at Interfaces’ (http://www.inflammation-at-interfaces.de, no: EXC306 and EXC306/2) and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) program e:Med sysINFLAME (http://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/5111.php, no: 01ZX1306A).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Sequencing and clinical data of the patient samples used in this study can be applied for via the Popgen Biobank (Institute of Epidemiology, Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Germany).

References

- 1. Lemoinne S, Kemgang A, Ben Belkacem K, et al. Fungi participate in the dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 2020;69:92–102. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kummen M, Holm K, Anmarkrud JA, et al. The gut microbial profile in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis is distinct from patients with ulcerative colitis without biliary disease and healthy controls. Gut 2017;66:611–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rühlemann M, Liwinski T, Heinsen F-A, et al. Consistent alterations in faecal microbiomes of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis independent of associated colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:580–9. 10.1111/apt.15375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor DL, Walters WA, Lennon NJ, et al. Accurate estimation of fungal diversity and abundance through improved lineage-specific primers optimized for Illumina amplicon sequencing. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016;82:7217–26. 10.1128/AEM.02576-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016;13:581–3. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nilsson RH, Larsson K-H, Taylor AFS, et al. The unite database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D259–64. 10.1093/nar/gky1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang XW, Yang FY, Meijer M, et al. Redefining Humicola sensu stricto and related genera in the Chaetomiaceae. Stud Mycol 2019;93:65–153. 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burns N, Arthur I, Leung M, et al. Humicola sp. as a cause of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:3081–5. 10.1128/JCM.01253-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katt J, Schwinge D, Schoknecht T, et al. Increased T helper type 17 response to pathogen stimulation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2013;58:1084–93. 10.1002/hep.26447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakamoto N, Sasaki N, Aoki R, et al. Gut pathobionts underlie intestinal barrier dysfunction and liver T helper 17 cell immune response in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:492–503. 10.1038/s41564-018-0333-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]