Abstract

A mouse model that replicates the clinical features of the most common form of heart failure opens a window on the mechanisms underlying this disease, and could help scientists to explore future therapies.

Heart failure is a lethal condition that affects at least 26 million people worldwide1. A preclinical model that faithfully recapitulates the most common form of this syndrome, known as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), has been lacking. On page 351, Schiattarella et al.2 report the development of a mouse model of HFpEF, and its use to identify a molecular pathway not previously known to have a role in this disease.

Heart failure has generally been seen as an inability of the heart to pump sufficient blood to meet the metabolic needs of the body. The weakening of the heart muscle is quantified by measuring the reduction in the percentage of blood in the heart expelled with each heartbeat, which is called the ejection fraction. This syndrome is referred to as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)3. But in more than half of cases of heart failure, ejection fraction remains normal, although abnormalities in heart-muscle contraction can be detected with more sensitive tests. This form of heart failure is called HFpEF and is defined by impaired filling of the heart with blood4. Dysfunction in other organs, including the lungs, kidneys and skeletal muscles, is also likely to contribute to the symptoms of the disease.

Although the two forms of heart failure have similar symptoms, including shortness of breath, reduced ability to exercise, and fatigue, their mechanisms differ markedly. HFrEF is characterized by persistent activation of stress-associated molecular pathways in heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes), leading to a decrease in the ability of these cells to contract, or to cell death. By contrast, HFpEF is driven by ageing, high blood pressure, metabolic changes associated with obesity and diabetes, and generalized chronic inflammation. These factors induce alterations in several cell types in the heart.

In HFpEF, the endothelial cells that line small blood vessels in the heart become dysfunctional and fail to synthesize adequate amounts of nitric oxide (NO), a substance involved in the relaxation of blood vessels. Connective-tissue cells called fibroblasts generate scarring. And the cardiomyocytes themselves become stiffer because of changes related to proteins involved in molecular signalling pathways and cellular contraction5. The end result is sluggish filling of the heart.

None of the existing therapies for HFrEF helps in HFpEF, and a good animal model for HFpEF has been lacking. Modelling HFpEF is challenging because of the complex interplay of many contributing factors and the plethora of clinical manifestations of the disease. Rather than recreating all the stimuli that lead to HFpEF, Schiattarella et al. combined two major risk factors — obesity linked with glucose intolerance (an inability to transport sugar efficiently from the blood into cells, which can lead to diabetes) and high blood pressure — in mice. The authors’ reasoning was that each of these factors activates several disease-associated pathways.

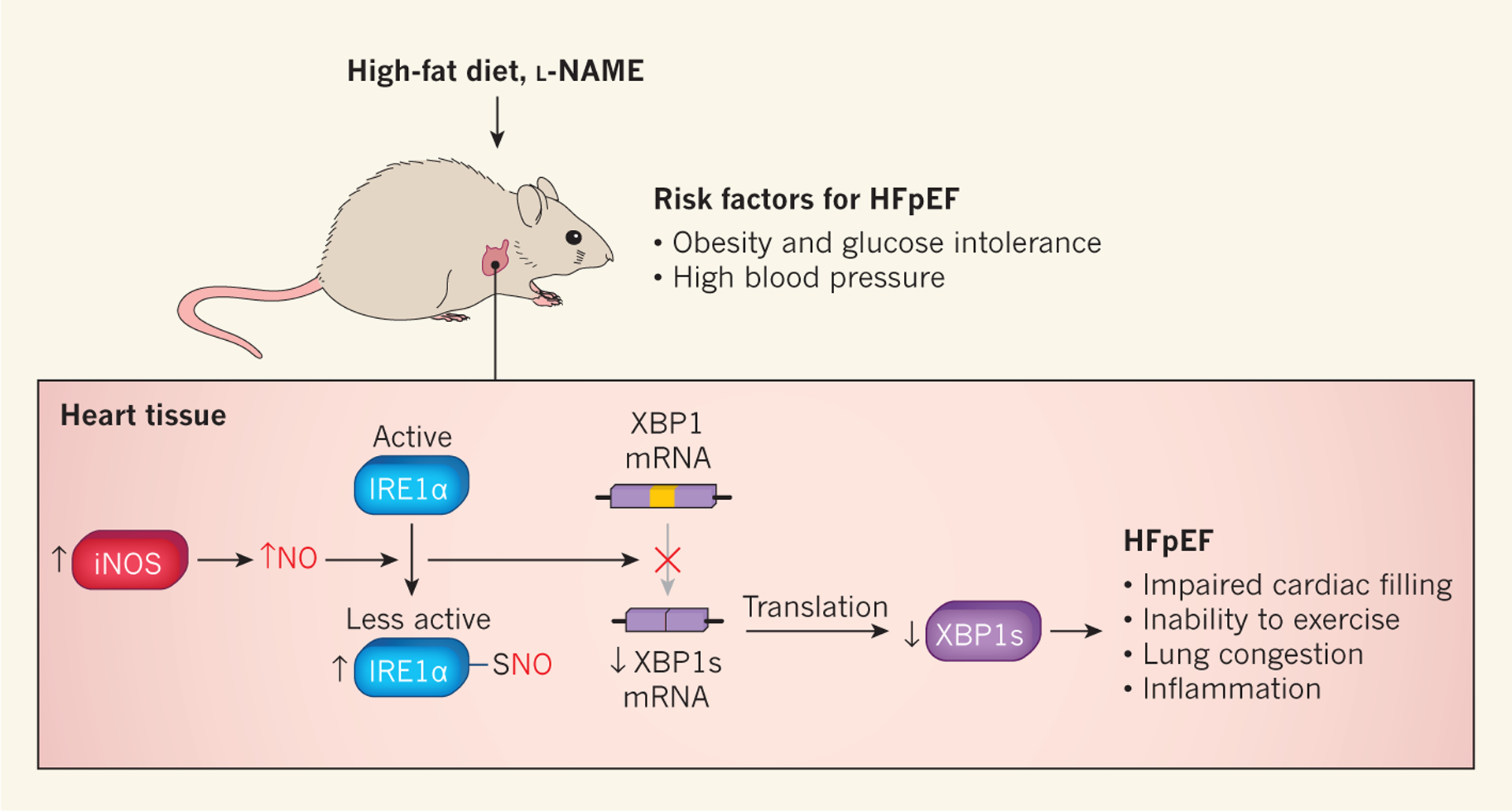

Mice were rendered obese and glucose-intolerant with a high-fat diet. High blood pressure was induced by administration of a drug called Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), which inhibits the enzymes that are normally expressed at constant levels to catalyse the production of NO (called constitutive NO synthases). Mice treated in this way had several characteristics of HFpEF, including impaired filling of the heart, inability to exercise, lung congestion and increased levels of molecular markers of inflammation in the heart and blood (Fig.1). Notably, ejection fraction in these mice remained normal up to at least 12 months of age, which is half the lifespan of a mouse.

Figure 1 |. Inhibition of the unfolded protein response contributes to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Schiattarella et al.2 fed mice a high-fat diet to produce obesity and glucose intolerance (an inability to transport sugar efficiently from the blood into cells, which can lead to diabetes), and gave the animals the drug Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) to cause high blood pressure. These treatments induced some of the hallmarks of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), including impaired filling of the heart with blood, inability to exercise, lung congestion and increased levels of molecular markers associated with inflammation. The authors also observed increased expression of the enzyme inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which increases the production of nitric oxide (NO). The addition of NO to sulfur atoms (S-nitrosylation) of inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) decreases this protein’s activity. IRE1α is a component of the unfolded protein response (UPR), a mechanism that protects cells against abnormal levels of misfolded proteins. Decreased IRE1α activity leads to reduced conversion (splicing) of messenger RNA encoding X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) to the mRNA that encodes XBP1 spliced (XBP1s), a transcription factor that activates UPR genes. The authors observed that IREα splicing activity and XBP1s levels were reduced in their mouse model of HFpEF.

The authors then used their model to investigate the role of misfolded proteins in HFpEF. These proteins accumulate in several disorders in which cardiac stress is present6, including HFpEF, and they activate a molecular program known as the unfolded protein response (UPR)7. Schiattarela et al. focused on inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), which is activated in response to cellular stress caused by an excess of misfolded proteins. IRE1α cuts the messenger RNA that encodes X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) and transforms it into a shorter mRNA that encodes a protein called XBP1 spliced (XBP1s). XBP1s is a transcription factor that activates genes involved in the UPR.

Schiattarella and colleagues found that IRE1α activation and XBP1s levels were reduced in the hearts of HFpEF model mice, as well as in heart-tissue samples from people with HFpEF, when compared with those from healthy individuals (Fig. 1). By contrast, cardiac XBP1s levels were increased or unchanged in mice and humans with HFrEF. The decrease in XBP1s levels in the hearts of HFpEF mice was due to IRE1α modification by S-nitrosylation. This process, in which an NO molecule is attached to specific sulfur atoms on proteins, is known to decrease IRE1α activity8.

Although Schiattarella et al. did not identify the cells that produce NO, they observed that inducible NO synthase (iNOS), an enzyme that was highly expressed in their HFpEF model, promoted IRE1α S-nitrosylation. They went on to show that pharmacological or genetic inhibition of iNOS or cardiomyocyte-specific over-expression of XBP1s attenuated cardiac filling defects, the inability to exercise, and lung congestion in mice induced to develop features of HFpEF. These findings highlight the role of XBP1s loss in the mechanisms underlying this disease.

“The work demonstrates that two common risk factors are sufficient to reproduce many of the manifestations of this disease”

This work demonstrates that two common risk factors for HFpEF are sufficient to reproduce many of the manifestations of this disease. The authors’ mouse model will be useful for dissecting disease mechanisms and developing new treatments. Although large-animal models are often valuable in studying complex physiological processes and testing therapeutics, the mouse has the advantage of being easy to manipulate genetically and having a short lifespan9. The latter factor will also facilitate the study of the influence of ageing, another key risk factor for HFpEF.

Some questions remain unanswered. The less-than-complete reversal of HFpEF disease manifestations observed in response to iNOS inhibition suggests that other molecular pathways are also involved in the reduction of XBP1s levels. More generally, the study explored a single candidate mechanism for this disease. It is likely that other mechanisms also contribute, and the new HFpEF mouse model provides an in vivo platform with which to define them.

References

- 1.Savarese G & Lund LH Card. Fail. Rev 3, 7–11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiattarella GG et al. Nature 568, 351–356 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom MW et al. Nature Rev. Dis. Primers 3, 17058 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlay SM, Roger VL & Redfield MM Nature Rev. Cardiol 14, 591–602 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SJ et al. Circulation 134, 73–90 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang ZV & Hill JA Cell Metab 21, 215–226 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter P & Ron D Science 334, 1081–1086 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L et al. Science 349, 500–506 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valero-Muñoz M, Backman W & Sam FJ Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic Transl. Sci 2, 770–789 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]