Abstract

South Carolina ranks 16th in the USA for highest rates of teenage pregnancy. The South Carolina Comprehensive Health Education Act (CHEA) does not require medically accurate, unbiased, culturally appropriate materials, and varies greatly in compliance and implementation. This study aimed to better understand parents’ perspectives in one county in South Carolina regarding reproductive and sexual health education. A total of 484 parents responded to a qualitative questionnaire, collectively representing 798 students. Researchers conducted a thematic analysis to organise data. Main themes identified include comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education as a duty; dispelling the myth of abstinence-only education; and the value of comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education. Parents described teaching reproductive sexual health education in public schools as a ‘duty.’ Furthermore, parents rejected the idea that abstinence-only education is effective and believed reproductive and sexual health education should be taught without the influence of religion. Parents valued inclusive reproductive and sexual health education, covering a robust set of topics. Findings from the study provide evidence for the need to update current reproductive and sexual health education materials and legislation to meet parental demands and reduce youth sexual and reproductive health disparities.

Keywords: parents, parental views, comprehensive sexual education, South Carolina, sexual health

Background

Teenage pregnancy often results in negative outcomes for women, infants and communities including poorer educational, behavioural and health outcomes compared to children born to older parents (Hoffman and Maynard 2008). Despite recent declines in teenage pregnancy, including an eight percent decrease from 2014 to 2015, the USA faces higher rates of teenage pregnancy than other high-income nations (CDC 2016; Finer and Zolna 2016). Lower socioeconomic status and education levels for teenagers and parents may contribute to increased incidence of teenage pregnancies (Penman-Aguilar et al. 2013). In 2015, teenage pregnancy cost US taxpayers 3.7 billion dollars, including costs for publicly funded nutrition, health care, and childcare assistance programmes (Frost et al. 2014). Furthermore, teenage pregnancy contributes to increased rates of incarceration, a cycle of lower educational attainment, and unemployment for teenage parents and their children (CDC 2016; Hoffman and Maynard 2008).

South Carolina, USA

In South Carolina, the teenage birth rate decreased by nine percent from 2015 to 2016. However, South Carolina ranks 16th in the USA for highest rates of teenage pregnancy (Martin et al. 2018). The public burden of teenage pregnancy costs South Carolina taxpayers an estimated $166 million annually (SC Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy 2018). Further, South Carolina reports high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), ranking 7th in the nation for rates of Chlamydia and 9th for gonorrhoea, and over half of all South Carolina high school students (aged 14-18 years) reported having sex in 2017 (CDC 2017; South Carolina Department of Education 2017).

South Carolina, along with 36 other states, mandates HIV or reproductive health education (South Carolina Legislature 1988). The South Carolina Comprehensive Health Education Act (CHEA), Title 59 Chapter 32, requires comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education be taught in public schools. The CHEA mandates that grades Kindergarten to 5 (i.e children aged 5-10 years) receive comprehensive health education; grades 6-8 (aged 11-13 years) receive comprehensive health education, including instruction on STIs; and at least seven hundred and fifty minutes of reproductive health and pregnancy prevention education be taught at least one time during the four years of high school. According to CHEA, ‘reproductive health education’ is defined as ‘instruction in human physiology, conception, prenatal care and development, childbirth, and postnatal care, but does not include instruction concerning sexual practices outside marriage or practices unrelated to reproduction except within the context of the risk of disease’ (South Carolina Legislature 1988). Furthermore, abstinence must be ‘strongly emphasized.’ (South Carolina Legislature 1988).

However, CHEA remains outdated by not requiring medically accurate, culturally appropriate and unbiased health information, the exclusion of information on gender and sexual minorities (i.e., non-heterosexual), and previously purposed amendments fail sufficiently to incorporate these requirements (Orekoya et al. 2016; South Carolina Legislature 1988). For example, proposed amendments advocate for the inclusion of defining ‘medically accurate’ health information, but not ‘culturally appropriate’ or ‘unbiased’ health information (e.g., without the influence of religion). Furthermore, large variations persist in materials and implementation of education curricula across the state and school districts (Orekoya et al. 2016).

The most recent state-wide survey on reproductive and sexual health education, conducted in 2005 among registered voters of South Carolina, found over three quarters of participants believed reproductive and sexual health education should emphasise abstinence-only education. Nearly all (88.4%) of the participants indicated the responsibility to teach reproductive and sexual health education falls on parents (Alton, Oldendick, and Draughon 2005). However, half of all participants indicated the number of reproductive and sexual health education should increase, and 70% believed the number of teenage pregnancy prevention programmes should increase in South Carolina (Alton, Oldendick, and Draughon 2005). A more recent focus-group study involving parents found parents desire a collaborative process, including a larger role from schools, to implement teenage pregnancy prevention programmes in South Carolina public schools (Rose et al. 2014).

Despite these previous findings, no changes have been made to CHEA since its introduction in 1988. CHEA’s outdated and limited standards, coupled with a conservative culture, may contribute to higher rates of poor health outcomes for South Carolina’s youth (Guttmacher Institute 2018; Orekoya et al. 2016). Research indicates parents may not be equipped with accurate, comprehensive knowledge to teach reproductive and sexual health education solely in the home (Elliott 2010; Heller and Johnson 2010; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016), therefore implementing medically accurate, unbiased school-based sexual education curricula may improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Comprehensive School-Based Reproductive and Sexual Health Education

Parents of adolescents indicate a need for comprehensive school-based sexual education in order to reduce teenage pregnancies and empower youth (M. E. Eisenberg et al. 2008; Howard et al. 2017; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016; Tortolero et al. 2011). Previous studies describe the benefits of comprehensive sexual education policies, including decreased incidence of teenage pregnancy, (Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty 2008) delay of sex initiation, (Kirby 2008) increased condom and contraceptive use, (de Castro et al. 2018; Kirby 2008) and more accurate sexual health knowledge (Grose, Grabe, and Kohfeldt 2014). Current school-based sexual education policies are often outdated (Greslé-Favier 2010), vary largely by state (Santelli et al. 2017), and emphasise abstinence-only sex education, which does not decrease incidence of teenage pregnancy (Carr and Packham 2017). Moreover, studies suggest abstinence-only reproductive and sexual health education does not delay initiation of sexual debut, (Kirby 2008; Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty 2008) and may contribute to higher rates of teenage pregnancy due to lack of contraceptive counseling (Stanger-Hall and Hall 2011). This necessitates a comprehensive, inclusive understanding of stakeholders’ (i.e., parents of students) perspectives and opinions regarding school-based reproductive and sexual health education.

Survey data from previous studies indicate parents of children and young people overwhelmingly value school-based comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education that includes information on contraception, (Alton, Oldendick, and Draughon 2005; M. E. Eisenberg et al. 2008; Grose, Grabe, and Kohfeldt 2014; Tortolero et al. 2011) relationships and gender identity (M. E. Eisenberg et al. 2008; Simovska and Peter 2015). Focus group studies, including those with parents, teachers and school stakeholders, found reproductive and sexual health education curricula and teenage pregnancy prevention programmes should detail the ‘real life,’ honest consequences associated with sexual activity, include age appropriate materials, and should be standardised in delivery (M. Eisenberg et al. 2012; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016; Murray et al. 2014). Furthermore, parents detail how their own lack of sexual health knowledge creates an impetus for schools to teach these subjects (Elliott 2010; Heller and Johnson 2010; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016). Not only should reproductive and sexual health education address the needs and wants of parents, but also diverse groups of individuals, including gender non-conforming, lesbian, gay bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ) community members who otherwise remain marginalised from heteronormative reproductive and sexual health education materials (Hobaica and Kwon 2017).

Purpose of the Study

This study was conducted in Charleston County on behalf of the Charleston County Teen Pregnancy Prevention Council (CCTPPC). CCTPPC is a nonprofit organisation aiming to reduce teenage pregnancy and improve the quality of life in the Charleston community. To achieve its mission, the council provides teen age pregnancy data, community resources, contraceptive access, and effective teenage pregnancy prevention programmes (CCTPPC 2019). Community events held by CCTPPC found a common theme that parents felt their voices were not heard and frustration regarding the lengthy and late timing school board meetings, making it difficult to even attend.

In 2015, despite unanimous approval from the health advisory committee, the Charleston County school board rejected a new Making Proud Choices! comprehensive sex education curriculum. In 2016, the Charleston County School Board rejected a curriculum that would have allowed seventh and eighth graders to learn about pregnancy prevention techniques, including birth control methods and effective condom use, with their parents’ permission (Pan 2016). Most recently, parents were upset to find out that the health advisory committee (mandated by CHEA) is required to have three clergy members, as compared to only two health professionals, two parents, two teachers, two students and two other persons not employed by the local school district (Schiferl 2019).

Few existing studies exploring views on school-based reproductive and sexual health education offer qualitative or open-ended data from parents alone, thus limiting the representation and understanding of parents’ perspectives, opinions and values regarding school-based reproductive and sexual health education (Elliott 2010; Heller and Johnson 2010; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016; Murray et al. 2014). Furthermore, updated findings are needed in order to address the modern desires of South Carolina parents that may not be properly represented in older studies. Qualitative research provides in-depth insight into participants’ understandings. Against this background, the purpose of this study was to better understand the parental opinions related to sexual health education in Charleston County, South Carolina public schools. We expect findings to identify practical opportunities to meet the needs of parents and ultimately improve adolescent and teenage sexual health outcomes.

Methods

This qualitative study was part of a larger research project investigating the opinions of parents in Charleston County about preferred reproductive health education topics. A qualitative questionnaire was developed with open-ended questions designed to elicit in-depth and rich responses. Through the strategic use of open-ended questions, researchers elicited robust responses and stories from participants suitable for qualitative analysis (O’Cathain and Thomas 2004). Further, scholars suggest that web-based surveys offer the potential to increase participation from diverse, hard-to-access, and marginalised populations, who are often understudied (McInroy 2016; Wright 2005). Open-ended text responses were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The University of South Florida institutional review board (IRB) approved this study.

Data collection

Eligible participants included parents and caregivers with at least one child attending a Charleston County public school. Potential respondents were recruited through email, web-based listservs, social media (i.e., Facebook and Twitter) and word of mouth. Examples of the different social media pages and listservs included local churches, the Ryan White Program, the South Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault, the YWCA, Communities in Schools, multiple Charleston Mom Facebook groups and many other social media pages parents might frequent (posted by individual accounts as well as those of relevant organisations).

Recruitment materials included unbiased language to encourage participation: ‘Do you have a child attending Charleston County Public Schools? We want to hear from you! Please take 3 minutes to complete this survey on parental opinions related to reproductive health education in public schools.’ There was no compensation provided to participants. Researchers encouraged participants to share the survey with other parents in Charleston County, creating a ‘snowball’ sampling approach, meaning current study participants recruit additional participants to ‘keep the ball rolling’ and facilitate ongoing recruitment (Berg and Lune 2012). Participants completed an anonymous, self-administered, online questionnaire through REDCap, a secure web application. espondents provided brief demographic details to ensure responses represented a diverse segment of the population. Computer IP addresses were limited to one submission to minimise multiple attempts from the same participant during the data collection period. Participants provided informed consent to proceed to the questionnaire, which respondents completed in approximately 5-15 minutes.

Exploratory open-ended questions were developed in collaboration with the Charleston County Teen Pregnancy Prevention Council and a review of the literature to facilitate inductive qualitative data analysis. . Sample questions included “The South Carolina Comprehensive Health Education Act requires that reproductive health in public schools emphasise abstinence as the first and best option for youth. Do you think that public schools should also teach youth about contraception and condoms as methods to prevent unwanted pregnancy and/or sexually transmitted diseases (including how to use these methods correctly)? Why or why not?”, and “Which of these topics (e.g., male and female reproductive anatomy, abstinence, parenting responsibilities, physical changes associated with puberty, STIs, HIV/AIDS, sexual abuse/rape, negotiation skills, contraception, condoms, pregnancy and childbirth, sexual orientation/gender identity) do you believe should be part of school-based sex education programmes, and what do you think is the earliest grade level at which it should be taught?”

In addition, participants were reminded that researchers were interested in parental opinions related to reproductive health education in public school and were encouraged to use as much space as they needed to share relevant details.

Data analysis

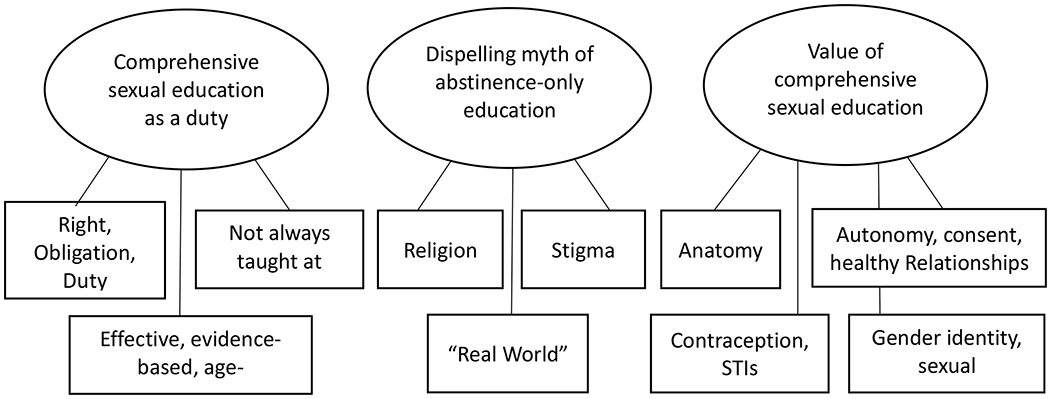

Thematic analysis methodology was used to offer a robust, thick description of these data, meaning a detailed and complex description of participants’ subjective experiences with appropriate context (Braun and Clarke 2006). Thematic analysis offered a recursive process to identify, analyse and report themes. Qualitative data analysis software HyperRESEARCH 3.7.3 was used to assist the analysis. Researchers followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six phases of analysis, including (1) familiarisation with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. This process involved seeking repeated patterns of meaning across the open-ended textual responses (Braun and Clarke 2006). Initially, the analytic process included description and organisation to reveal patterns in the data. Similar to a codebook, researchers defined and refined a thematic map, which provides a visual conceptualisation of patterns in the data, including the relationships between codes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Figure 1 shows the final three main themes and subthemes.

Figure 1. Final thematic map, showing final three main themes.

Design based on Braun & Wilkinson, 2003

Findings

A total of 484 participants responded to the survey. Participants reported an average age of 41.25 ± 15.97 and overwhelmingly self-identified as female (n = 438, 90.5%) and white (n = 412, 85.1%), which is considerably larger than the 48% of white students represented in Charleston County School District. A smaller portion of the respondents self-identified as Black/African American (n = 43, 8.9%), much lower than the 38% of black students in Charleston County School District (Charleston County School District 2019).

Most participants self-reported an Associate’s Degree or higher for level of education obtained (n = 450, 93%), while the remaining participants reported an education level of a GED or lower (n = 29, 6%), reflective of Charleston County where 91% of adults report their education level as higher than a high school diploma (US Census Bureau 2018). The majority of participants indicated they had one child (n = 236, 48.8%) enrolled in a Charleston County public school, followed by two children (n = 194, 40.1%), three children (n = 44, 9.1%), four children (n = 8, 1.7%), and five children (n = 2, 0.4%). Participants represented 496 (62.1%) elementary school students, 163 (20.5%) middle school students, and 112 (14%) high school students. Overall, the sample represented a total of 798 students enrolled in Charleston County School District, which serves 49,820 students. See Table 1 for all participant demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristic

| N = 484 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Under 29 | 15 (3.1) |

| 30 – 39 | 204 (42.1) |

| 40 – 49 | 200 (41.3) |

| 50 – 59 | 58 (12.0) |

| ≥ 60 | 7 (1.4) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 438 (90.5) |

| Male | 40 (8.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 412 (85.1) |

| Black/African American | 43 (8.9) |

| Other | 9 (1.8) |

| Hispanic | 10 (2.1) |

| Non-Hispanic | 427 (88.2) |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| Some High School | 2 (0.40) |

| High School Diploma or GED equivalent | 27 (5.6) |

| Associate degree | 44 (9.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 180 (37.2) |

| Graduate Degree | 226 (46.7) |

| Number of Children in Charleston County Public School | |

| 1 Child | 236 |

| 2 Children | 194 |

| 3 Children | 44 |

| 4 Children | 8 |

| 5 Children | 2 |

| Grade Level of Children | |

| Elementary | 496 (62.2) |

| Middle School | 163 (20.4) |

| High School | 112 (14.0) |

Note. Frequencies that do not sum due to “prefer not to answer” response.

Three themes, with related subthemes were identified regarding parental attitudes toward sex education in Charleston County public schools: 1) Comprehensive Reproductive and Sexual Health Education as a Duty: Right, Obligation, Duty; Effective, Evidence-Based, Age-Appropriate Education; and Not Always Taught at Home; 2) Dispelling the Myth of Abstinence-only Education: Religion; ‘Real World;’ and Stigma; and 3) The Value of Comprehensive Reproductive and Sexual Health Education: Male and Female Reproductive Anatomy; Bodily Autonomy, Consent, and Health Relationships; and Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation. Results include representative quotes chosen to best reflect patterns and themes in the data as well as to honor the unique voices of participants, therefore each comment is from a different participant.

Comprehensive Reproductive and Sexual Health Education as a Duty

Right, Obligation, and Duty

Participants viewed teaching comprehensive sex education as a public school’s obligation to students. One 38-year-old mother with a graduate degree said, ‘we have an obligation to inform youth of the options available.’ Many participants indicated that students had the right to knowledge about their bodies and withholding education was not only a disservice, but also harmful. According to another 63-year-old mother with a graduate degree, ‘not telling [students] about contraception and sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention is pure negligence.’ Most participants believed that providing knowledge about sexual health-related topics can empower students to take control of their health.

Participants also invoked duty as a reason to provide comprehensive sex education. According to one participant, a 45-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘South Carolina ranks in the top #5 out of 50 states with the highest incidence of Chlamydia and gonorrhoea. We need to educate our youth.’ Another 43-year-old mom with a graduate degree noted the correlation that ‘the states with abstinence-only sex education have the highest rates of pregnancy.’ Participants understood comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education as a student’s right, which could reduce rates of STIs and teen pregnancy.

Effective, Evidence-based, Age-appropriate Education

In addition to the right to education, parents suggested comprehensive sex education should comprise effective, scientific, evidence-based and age-appropriate material. According to one 32-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘data show that comprehensive sex education is more effective than an abstinence-only approach at reducing the rates of teen pregnancy and STIs.’ Parents regularly reaffirmed that comprehensive sex education is proven effective in reducing rates of STIs and teenage pregnancy.

Overall, participants favoured comprehensive sex education, but some had concerns about its implementation. For example, one 39-year-old mother with a graduate degree, although comfortable with comprehensive sex education, warned ‘all of these topics should be approached in a developmentally appropriate way.’ In addition to concerns about age-appropriateness, some participants were concerned about the qualifications of instructors teaching sex education. According to one 34-year-old mother with a graduate degree, ‘anything related to medicine (like contraception) should not be taught in schools by teachers that have NO medical background to be able to discuss the risk factors associated with different types of medicine.’ Although participants expressed concerns, parents also recognised the benefits of comprehensive sex education as effective when appropriately implemented.

Not always taught at home

Many participants expressed the importance of teaching evidence-based, comprehensive sex education because it is not always taught at home. One 41-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree stated, ‘I would guess that a lot of children might not have the benefit of a responsible adult helping them become properly educated in this area.’ According to one 39-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘although I think abstinence is best, there are some who will be sexually active, and parents may not be teaching proper methods at home.’ Regardless of personal views on abstinence, participants felt an obligation to implement comprehensive sex education as part of the public-school curriculum because students may not receive this education at home.

Dispelling the Myth of Abstinence-Only Education

Religion

Participants viewed the religious beliefs of others as a barrier to comprehensive sex education in schools. Some participants were frustrated by what they viewed as an encroachment of religion concerning the inclusion of sex education in schools. One 42-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree said, ‘keep religion out of our public institutions and teach children about the human body, biology, reproduction and STDs.’ According to a 54-year-old mother with a graduate degree, ‘our kids and teens deserve better than religious lies that are not based on evidence or facts.’ For these participants, religion played a disproportionate role in the conversation around sex education in schools.

On the other hand, many participants cited their personal religious views as the basis for their support of comprehensive sex education. One 43-year-old mother with a graduate degree said:

As a Christian parent, I hold the view that the tension of ‘freedom and responsibility’ is the best way to raise children, but the natural consequence of sex is likely conceiving a baby, so in my view prevention and education is in order for a healthy society.

Many participants recognised the tension between religious teachings of abstinence, and the practical responsibility of creating a ‘healthy society,’ which requires comprehensive sex education.

Real World

In addition to religion, participants described the impact of media and popular culture as a reason for comprehensive sex education in schools. One 35-year-old mother with a graduate degree said, ‘the reality is that teens have sex, and I prefer my son understand how to protect himself and his partner from pregnancy and diseases.’ Many participants viewed sex as an inevitability for teenagers, and abstinence-only education depended on the myth that teenagers do not engage in sexual activity. Another 47-year-old mother with a graduate degree cited the media as a reason for comprehensive sex education in schools, stating ‘teens are sexually active. Promiscuity is all over mainstream television, magazines and the internet.’ Most participants recognised abstinence as unrealistic for students, and abstinence-only education as ineffective.

Stigma

Participants described the need to diminish the stigma surrounding sex education. According to one 40-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘we have to stop making sex a taboo topic. Kids are full of false ideas because no one is providing them with accurate information.’ Many participants advocated for comprehensive sex education in schools to correct misinformation and address the stigma around sexual health-related topics. Other participants discussed stigma and the need for education in the context of their own histories. One 36-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree described how they, ‘grew up in an upper-class religious household, as did my friends. I started having sex at 14. My friends were all having sex around me.’ Despite an upbringing in a conservative environment, this same participant engaged in sexual activity as a young person and advocated for comprehensive sex education in schools in order to teach safe practices and help young people make better decisions.

The Value of Comprehensive Reproductive and Sexual Health Education

Male and Female Reproductive Anatomy

Several participants noted the importance of teaching anatomy, including the use of scientifically accurate language, as a key component of comprehensive sex education curricula. One 38-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree said, ‘I think that it is super important for kids to know their anatomy and what happens with it. The correct terms are so important.’ Another 42-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree said, ‘I think it is important to also teach children that what they are feeling and how their body is changing is normal [emphasis by participant].’

Bodily Autonomy, Consent, and Healthy Relationships

Participants expressed support for a variety of topics in comprehensive sex education curricula regarding individual bodily autonomy. According to one 36-year-old mother with a graduate degree, ‘I believe sexual abuse prevention should be taught to all ages in a developmentally appropriate way.’ Participants also supported teaching about healthy relationships, ‘I believe sex ed should also include a HUGE [emphasis by participant] component about consent.’ Participants who expressed concerns over comprehensive sex education in schools were also in favour of topics related to bodily autonomy, according to a 45-year-old mother with a graduate degree: ‘abstinence should be promoted in a way that does not reinforce gender norms but rather emphasises respect between individuals.’ Despite different viewpoints about comprehensive sex education, participants believed that students should be taught about their right to control their own body.

Contraception and STIs

Another topic addressed by participants included contraception and STIs. Participants expressed interest in comprehensive sex education including discussions about birth control. According to one 51-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘we must…educate our children on the proper birth control methods to prevent unwanted pregnancies.’ This sentiment was echoed by another 51-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree saying, ‘I wish all girls could receive free birth control implants at age 13! They should at least be given as much information as possible about sex and birth control.’

Support for contraceptive information was stressed regardless of gender, ‘I have a teenager and stress the importance of using condoms to him…It would be nice to have this advice reinforced at school.’

STIs were also noted as an important topic to be included in comprehensive sex education in order to address misinformation. According to one 46-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘I’ve heard friends of my kids say they didn’t know they could get oral herpes from just kissing or other STIs from just “touching.”‘ One 39-year-old father with a bachelor’s degree explicitly outlined the need for this information stating, ‘knowledge is power, and a formalised curriculum including effectiveness and application of various birth control and STI prevention methods empowers our children.’

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Participants varied in their opinions regarding gender identity and sexual orientation being taught in schools. Despite differing viewpoints, participants discussed reducing stigma as a reason for discussing these topics. According to one 31-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree:

Teaching about sexual orientation and gender [identity] at a young age can help destigmatise and de-mystify it all, making it easier for children…to speak to their peers and transition when they’re ready.

Some participants had mixed feelings about gender identity and sexual orientation being taught in school. According to one 35-year-old mother with an associate degree:

Not sure how I feel about school addressing sexual orientation or gender identity, but I realise it is a conversation one must have. My kids are still very young, so I am still grappling with how to handle this on the most basic level for such discussions.

For most participants, there was a tension between recognising that students should learn about gender identity and sexual orientation and the need for the conversation to be developmentally appropriate.

Even participants who were uncomfortable with schools teaching about gender identity and sexual orientation expressed support and inclusion for LGBTQ students. According to one 52-year-old mother with a bachelor’s degree, ‘sexual orientation should not be a school topic, it should be taught by parents…That being said, sexual orientation should not be a putdown in any school setting, nor should such bullying be tolerated.’ This same participant was opposed to gender identity and sexual orientation being taught in schools while wanting to ensure students with non-normative identities were included and not subjected to bullying.

Discussion

Four hundred and eighty-four parents, representing a total of 798 students, responded to a questionnaire aimed at understanding parental attitudes toward sex education in local public schools. Participants believed public schools have a duty to teach comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education. Findings show that reproductive and sexual health education curricula should be effective, evidence-based, science-based, age-appropriate and taught by trained teachers or instructors. Many participants perceived a lack of reproductive and sexual health education being taught at home, resulting in an obligation to include reproductive and sexual health education in a school setting. Participants rejected the idea of abstinence-only as an effective approach to reproductive and sexual health education. Many participants cited the impact of religious beliefs, the reality of adolescent sexual activity, sexual content in media, and stigma on discussions of sexual and reproductive health topics. Finally, most parents agreed that reproductive and sexual health education should include a robust set of topics including reproductive anatomy, bodily autonomy and consent, contraception and gender identity and sexual orientation.

Reproductive and Sexual Health Education as a Duty

Parents believed schools are obligated to provide effective, evidence-based, and age-appropriate reproductive and sexual health education. This reinforces previous research suggesting parents believe schools need to ‘do more,’ including teaching about STI prevention, condom use and contraceptive methods (Tortolero et al. 2011). This finding also supports research suggesting parents lack the necessary, in-depth knowledge to effectively teach myriad sexual health topics to their children at varying ages within the home (Elliott 2010; Heller and Johnson 2010; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016).

This assertion by parents for trained sexual health education instructors in schools coupled by lack of adequate in-home instruction from parents establishes an imperative, or ‘duty,’ for school-based sexual health educators to deliver effective, age-appropriate sexual health education. It offers an updated perspective on findings from a 2005 survey of South Carolina residents, of a similar demographic composition (72% white, and 59% female), that indicated parents and/or legal guardians should hold the responsibility to teach reproductive and sexual health education (Alton, Oldendick, and Draughon 2005). Mandating the comprehensive coverage of sexual health topics in public schools through policy may close the knowledge gap created by limited or absent in-home instruction, protect students and reduce sexual health disparities experienced by youth across age groups. This finding also supports the updating of CHEA to create a more standardised administration of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health education to ensure students receive adequate information regardless of parents’ teaching.

Effective Abstinence-Only is a Myth

Parents perceived effective abstinence-only reproductive and sexual health education as a myth. This finding supports research that indicates abstinence-only education does not reduce teenage pregnancy rates (Carr and Packham 2017). Curricula should be comprehensive, developed without the influence of religious beliefs, recognise the reality of media influence on adolescent sexual behaviour, and attempt to normalise sexual and reproductive health discussions. This finding extends previous research indicating parents believe school-based reproductive and sexual health education should cover the ‘realities’ and the potential consequences of risky sexual behaviours among adolescents (Murray et al. 2014; Tortolero et al. 2011). Research suggests equipping adolescents with the necessary skills to navigate and communicate sexual health decision making and sexual encounters contributes to healthier relationships (Decker, Berglas, and Brindis 2015; Elliott 2010; Orekoya et al. 2016). Incorporating ‘real world’ influences and consequences into reproductive and sexual health education may normalise sexual health discussions and empower youth to make positive sexual and reproductive health decisions.

Parents’ stated need for unbiased reproductive and sexual health education (i.e., without the influence of religion) demonstrates that South Carolina’s reproductive and sexual health education legislation (CHEA) requires further reform in order to meet the modern desires of South Carolina parents. Stimulating policy change by improving CHEA via standardising and mandating the provision of unbiased school-based reproductive and sexual health education holds the potential to optimise educational materials and instructor time and efforts in order to ameliorate adolescent sexual health disparities. It is imperative, however, that updated amendments to CHEA not only define ‘unbiased’ health information, but also include training for reproductive and sexual health educators to ensure unbiased, culturally appropriate delivery of education materials.

Reproductive and Sexual Health Education is Inclusive

Parents value inclusive, comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education. Reproductive and sexual health education curricula should include age-appropriate discussions of male and female reproductive anatomy, bodily autonomy, consent, healthy relationships, contraception, and gender identity and sexual orientation. This finding mirrors previous research showing that parents value comprehensive reproductive and sexual health education beyond abstinence-only, including information on contraception, relationships and gender identity (M. E. Eisenberg et al. 2008; Johnson-Motoyama et al. 2016; Simovska and Peter 2015; Tortolero et al. 2011).

Beyond this, these qualitative findings provide novel insight to specific topics parents value in reproductive and sexual health education materials that may not be covered in previous survey studies, including gender identity and sexual orientation, bodily autonomy and consent. Parents believed including information on gender identity and sexual orientation can destigmatise these topics, challenging previous survey data that indicate over half of South Carolina residents surveyed do not want information on ‘homosexuality’ included in school-based reproductive and sexual health education (Alton, Oldendick, and Draughon 2005). This further revidences the evolving views of South Carolina. CHEA should be updated to not exclude information on ‘alternative sexual lifestyles’ in order to address materials that parents of children within the public-school system desire to be taught.

Parents expressed concern that they lack comprehensive understanding of issues related to gender identity and sexual orientation, emphasising that these topics should be covered in school-based reproductive and sexual health education. Participants suggested addressing these topics may reduce misunderstandings and bullying and contribute to creating a safe space in public schools. This parental perspective contributes to previous research among sexually diverse youth who believed inclusive reproductive and sexual health education may contribute to a better sense of community and potentially safer sex practices (Hobaica and Kwon 2017; Snapp et al. 2015). In-depth understanding of parents’ values and reasoning for the inclusion of specific topics demands reproductive and sexual health education materials be complete, including sexual orientation and gender identity, to ensure the wellbeing and safety of all students.

Limitations

Several limitations exist in the present study. Survey data obtained includes insights from South Carolina parents from within one county, therefore generalisability to other regions of South Carolina and the USA i limited. Although the study surveyed a select group of Charleston County residents (i.e., parents with children in public schools), participant demographics (e.g., race and gender) may not fully represent or reflect those of all Charleston County residents. Future research should seek to include more diverse participants, including men and parents of colour. In addition, qualitative data obtained via surveys may not address parents’ thoughts and opinions as comprehensively as other qualitative methodologies. Future studies should employ other qualitative methodologies including in-depth interviews or focus groups to add more in-depth understanding of parental perspectives of reproductive and sexual health education.

Future Implications

Study findings offer novel and updated insights to the perspectives, opinions, and values among parents for school-based reproductive and sexual health education materials, topics and implementation. In particular, they evidence the critical need to increase oversight and documentation of the reproductive and sexual health taught to youth in schools to ensure realisation of current and future policies. Abstinence-only and other outdated sexual and reproductive health policies and curricula do not contribute to lower rates of teenage pregnancy (Carr and Packham 2017). The 1988 CHEA policy is 31 years old and, as indicated in previous studies and the current study, the perspectives and needs of parents and students evolve over time, therefore CHEA must be updated. For example, CHEA currently requires information that is ‘age-appropriate,’ but allows the school board to determine what is deemed age-appropriate, without consideration of parental perspectives. This study provides insight to parental views of ‘age-appropriate’ sexual and reproductive health topics and explicit information parents wish to be included in updated school-based reproductive and sexual health education policies.

Future research should also examine the qualifications and training of reproductive and sexual health education teachers and instructors to ensure effective presentation of updated curricula. These results should guide the Charleston County School Board, and potentially South Carolina legislation, to ensure the needs of parents and students are met to reduce sexual and reproductive health disparities faced by South Carolina youth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of the Women’s Health Research Team at the College of Charleston and the Charleston County Teen Pregnancy Prevention Council for their support and collaboration on the project.

Funding

This project was supported, in part, by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the US National Institutes of Health under Grant Number UL1 TR001450. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests to report.

References

- Alton Forrest, Oldendick Robert, and Draughon Katherine. 2005. “The Sex Education Curriculum in South Carolina’s Public Schools: The Public’s View.” Public Policy & Practice 4 (1): 1–14. http://www.ipspr.sc.edu/ejournal/ejmay05/sexrev3.htm [Google Scholar]

- Berg Bruce L, and Lune Howard. 2012. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Braun Virginia, and Clarke Victoria. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Braun Virginia, and Wilkinson Sue. 2003. “Liability or Asset? Women Talk about the Vagina.” Psychology of Women Section Review 5 (2): 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Carr Jillian B., and Packham Analisa. 2017. “The Effects of State-Mandated Abstinence-Based Sex Education on Teen Health Outcomes.” Health Economics 26 (4): 403–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro Filipa de, Rojas-Martínez Rosalba, Villalobos-Hernández Aremis, Allen-Leigh Betania, Breverman-Bronstein Ariela, Billings Deborah Lynn, and Uribe-Zúñiga Patricia. 2018. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes Are Positively Associated with Comprehensive Sexual Education Exposure in Mexican High-School Students.” Edited by Dalby Andrew R.. PLOS ONE 13 (3). 10.1371/journal.pone.0193780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCTPPC. 2019. “Charleston County Teen Pregnancy Prevetion Council: About Us.” Charleston County Teen Pregnancy Prevention Council; November 2019. https://www.cctppc.com. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2016. “About Teen Pregnancy | Teen Pregnancy | Reproductive Health | CDC.” April 26, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/index.htm

- ———. 2017. “Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2016.” Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Charleston County School District. 2019. “Fast Facts.” Charleston County School District Schools; 2019. https://www.ccsdschools.com. [Google Scholar]

- Decker Martha J., Berglas Nancy F., and Brindis Claire D.. 2015. “A Call to Action: Developing and Strengthening New Strategies to Promote Adolescent Sexual Health.” Societies (2075-4698) 5 (4): 686. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg Marla E., Bernat Debra H., Bearinger Linda H., and Resnick Michael D.. 2008. “Support for Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Perspectives from Parents of School-Age Youth.” Journal of Adolescent Health 42 (4): 352–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg Marla, Madsen Nikki, Oliphant Jennifer A., and Resnick Michael. 2012. “Policies, Principals and Parents: Multilevel Challenges and Supports in Teaching Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 12 (3): 317–29. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Sinikka. 2010. “‘If I Could Really Say That and Get Away with It!’ Accountability and Ambivalence in American Parents’ Sexuality Lessons in the Age of Abstinence.” Sex Education 10 (3): 239–50. [Google Scholar]

- Finer Lawrence B., and Zolna Mia R.. 2016. “Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011.” The New England Journal of Medicine, no. 9: 843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost Jennifer J., Sonfield Adam, Zolna Mia R., and Finer Lawrence B.. 2014. “Return on Investment: A Fuller Assessment of the Benefits and Cost Savings of the US Publicly Funded Family Planning Program: US Publicly Funded Family Planning Program.” Milbank Quarterly 92 (4): 696–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greslé-Favier Claire. 2010. “The Legacy of Abstinence-Only Discourses and the Place of Pleasure in US Discourses on Teenage Sexuality.” Sex Education 10 (4): 413–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grose Rose Grace, Grabe Shelly, and Kohfeldt Danielle. 2014. “Sexual Education, Gender Ideology, and Youth Sexual Empowerment.” Journal Of Sex Research 51 (7): 742–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. 2018. “Sex and HIV Education.” Guttmacher Institute; 01 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education. [Google Scholar]

- Heller Janet R., and Johnson Helen L.. 2010. “What Are Parents Really Saying When They Talk With Their Children About Sexuality?” American Journal of Sexuality Education 5 (2): 144–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica Steven, and Kwon Paul. 2017. “‘This Is How You Hetero:’ Sexual Minorities in Heteronormative Sex Education.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 12 (4): 423–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman Saul D., and Maynard Rebecca A.. 2008. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Second edition Washington, D.C: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Howard Tiffany R., Larkin Lauri J., Ballard Michael D., McKinney Molly A., and Gore Jonathan S.. 2017. “Parental Views on Sexual Education in Public Schools in a Rural Kentucky County Eastern Kentucky University.” KAHPERD Journal 54 (2): 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Motoyama Michelle, Moses Mindi, Kann Tiffany, Mariscal E, Levy Michelle, Navarro Carolina, Fite Paula, Koloroutis Kann Tiffany, Mariscal E Susana, and Fite Paula J. 2016. “Parent, Teacher, and School Stakeholder Perspectives on Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Programming for Latino Youth.” Journal of Primary Prevention 37 (6): 513–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby Douglas B. 2008. “The Impact of Abstinence and Comprehensive Sex and STD/HIV Education Programs on Adolescent Sexual Behavior.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 5 (3): 18. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Pamela K., Manhart Lisa E., and Lafferty William E.. 2008. “Abstinence-Only and Comprehensive Sex Education and the Initiation of Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy.” Journal of Adolescent Health 42 (4): 344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A., Hamilton Brady E., Osterman Michelle J.K., Driscoll Anne K., and Patrick Drake. 2018. “Births: Final Data for 2017.” National Vital Statistics Reports 67 (8): 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInroy Lauren B. 2016. “Pitfalls, Potentials, and Ethics of Online Survey Research: LGBTQ and Other Marginalized and Hard-to-Access Youths.” Social Work Research 40 (2): 83–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Ashley, Ellis Monica U., Castellanos Ted, Gaul Zaneta, Sutton Madeline Y., and Sneed Carl D.. 2014. “Sexual Health Discussions between African-American Mothers and Mothers of Latino Descent and Their Children.” Sex Education 14 (5): 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cathain Alicia, and Thomas Kate J.. 2004. “‘Any Other Comments?’ Open Questions on Questionnaires – a Bane or a Bonus to Research?” BMC Medical Research Methodology 4 (1): 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orekoya Olubunmi, White Kellee, Samson Marsha, and Robillard Alyssa G.. 2016. “The South Carolina Comprehensive Health Education Act Needs to Be Amended.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (11): 1950–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Deanna. 2016. “Charleston County School Board Nixes Part of Sex Education Curriculum.” Post and Courier, October 24, 2016, Online edition. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/charleston-county-school-board-nixes-part-of-sex-education-curriculum/article_7e6f1846-9a09-11e6-b4df-e32fc56b9b8d.html.

- Penman-Aguilar Ana, Carter Marion, Snead M. Christine, and Kourtis Athena P.. 2013. “Socioeconomic Disadvantage as a Social Determinant of Teen Childbearing in the U.S.” Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974) 128 Suppl 1 (April): 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose India, Prince Mary, Flynn Shannon, Kershner Sarah, and Taylor Doug. 2014. “Parental Support for Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Programmes in South Carolina Public Middle Schools.” Sex Education 14 (5): 510–24. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli John S., Kantor Leslie M., Grilo Stephanie A., Speizer Ilene S., Lindberg Laura D., Heitel Jennifer, Schalet Amy T., et al. 2017. “Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact.” Journal of Adolescent Health 61 (3): 273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SC Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. 2018. “On Taxpayers | SC Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.” 2018. https://www.teenpregnancysc.org/issue/taxpayers

- Schiferl Jenna Schiferl. 2019. “Charleston Parents Slam SC Sex Ed Law Giving Clergy Members More Say than Health Experts.” Post and Courier, July 19, 2019, Online edition. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/charleston-parents-slam-sc-sex-ed-law-giving-clergy-members/article_1cbf7396-92a6-11e9-acbd-dbb5b801180f.html

- Simovska Venka, and Peter Christina R.. 2015. “Parents’ Attitudes toward Comprehensive and Inclusive Sexuality Education : Beliefs about Sexual Health Topics and Forms of Curricula.” Health Education, no. 1: 71. [Google Scholar]

- Snapp Shannon D., McGuire Jenifer K., Sinclair Katarina O., Gabrion Karlee, and Russell Stephen T.. 2015. “LGBTQ-Inclusive Curricula: Why Supportive Curricula Matter.” Sex Education 15 (6): 580–96. [Google Scholar]

- South Carolina Department of Education. 2017. “SC Youth Risk Behaviors Survey (YRBS) - South Carolina Department of Education.” 2017. https://ed.sc.gov/districts-schools/school-safety/health-safety-surveys/sc-youth-risk-behaviors-survey-yrbs/

- South Carolina Legislature. 1988. Title 59: Comprehensive Health Education Program. Act Vol. 437. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger-Hall Kathrin F., and Hall David W.. 2011. “Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S.” PLOS ONE 6 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero Susan R., Johnson Kimberly, Cuccaro Paula M., Markham Christine, Hernandez Belinda F., Addy Robert C., Shegog Ross, Li Dennis H., and Peskin Melissa. 2011. “Dispelling the Myth: What Parents Really Think about Sex Education in Schools.” Journal of Applied Research on Children 2 (2): 1. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. 2018. “Charleston County, South Carolina.” United States Census Bureau; July 1, 2018. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/charlestoncountysouthcarolina/PST045217 [Google Scholar]

- Wright Kevin B. 2005. “Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10 (3). 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]