Abstract

Mental health services are up to six times more likely than general medical services to be delivered by an out-of-network provider, in part because many psychiatrists do not accept commercial insurance. Provider directories help patients identify in-network providers, although directory information is often not accurate. We conducted a national survey of privately insured patients who received specialty mental health treatment. We found that 44 percent had used a mental health provider directory and that 53 percent of these patients had encountered directory inaccuracies. Those who encountered inaccuracies were more likely (40 percent versus 20 percent) to be treated by an out-of-network provider and four times more likely (16 percent versus 4 percent) to receive a surprise outpatient out-of-network bill (that is, they did not initially know that a provider was out of network). A federal standard for directory accuracy, stronger enforcement of existing laws with insurers liable for directory errors, and additional monitoring by regulators may be needed.

Psychiatrists are less likely than members of other medical specialties to participate in private insurance networks, with one-third of psychiatrists reporting that they do not accept new patients with private insurance.1 This may be due to low insurer reimbursement for in-network visits: Health plans pay substantially less for in-network mental health services than for services provided by other specialties.2–4 Workforce shortages mean that even without participating in private plans, psychiatrists may have enough demand for services to fill their patient panels.5 This makes it difficult for patients to locate an in-network mental health provider and may result in the patient not obtaining care or using an out-of-network provider. Mental health services are up to six times more likely than general medical services to be delivered by an out-of-network provider.4,6

Inaccurate information in health plans’ mental health provider directories may be compounding this problem. Patients use directories to locate an in-network provider or to determine whether a specific provider is in the plan’s network. Patients’ use of inaccurate information in directories may result in frustration, delays in care, the inability to locate a participating provider with available appointments, mistaken use of an out-of-network provider (that is, the receipt of a “surprise bill”),7 or the purchase of a plan without a preferred provider. Moreover, regulators, accreditors, and purchasers may rely on directory information to determine whether a plan has an adequate network.8,9

Audit and ”mystery shopper” studies indicate that there are significant errors in information related to psychiatrists in private plan directories.10–14 Yet these studies did not consider real-world patient experiences, which may differ from audit studies in important ways. First, whether patients use insurers’ mental health directories has not been studied, nor has whether and how often patients encounter incorrect information in such directories. Previous audit studies almost exclusively focused on psychiatrists, yet one-third of people whoreceive mental health care in the US are treated only by psychologists, social workers, or other nonpsychiatrist mental health providers.15 Perhaps most important, audit studies do not provide information about the association between patients’ experiences with directories and related consequences for treatment access. Focusing on the patient experience provides policy makers with a better understanding of the extent of this problem and its consequences.

To fill these gaps, we conducted a national survey of privately insured patients who used outpatient specialty mental health services. We examined whether participants had used a plan’s mental health directory in the past year and, among participants who had used a directory, whether they had encountered inaccurate information. Next, we examined whether encountering inaccurate information was associated with being treated by an out-of-network mental health provider and whether the participant knew that the provider was not in the network before the visit. Because many states rely on consumer complaints to gauge whether plans maintain network adequacy,16,17 we also considered whether patients who encountered inaccuracies filed a complaint about the mental health network.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCE

Data were obtained from a national internet survey of English-speaking US adults enrolled in commercial (private) insurance plans that was fielded in August and September 2018. Participants were recruited through KnowledgePanel, an online panel of approximately 55,000 households that was constructed through high-quality, address-based sampling using the US Postal Service Delivery Sequence File and that includes households with no phone, no internet, or only cell phones.18 The panel’s probability-based sampling and its close representativeness of the US population have been validated.19 The survey burden is limited to minimize fatigue and attrition, with panelists completing an average of two surveys per month. Panelists are incentivized through raffles for cash and other prizes and provided with internet access and hardware if needed. We constructed and tested the survey, which lasted six to fourteen minutes, through ten cognitive interviews to ensure that questions were understandable and eliminate questions that could not be reliably answered by self-report.20

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

A series of screener questions was sent to panelists ages 18–64 to identify participants enrolled in a private health insurance plan with a provider network. See online appendix exhibit A1 for the wording of relevant survey questions.21 Because we were particularly interested in experiences with out-of-network care and mental health care, we oversampled participants who had used mental health providers, whom we defined as professionals specifically trained to diagnose and treat emotional or mental health problems, including psychiatrists, therapists, psychologists, mental health nurse practitioners, and social workers. This study included the 861 panelists who had used outpatient specialty mental health services in the past twelve months (appendix exhibit A2).21

SURVEY DESIGN

We assessed participants’ use of the mental health directory, experiences with directory inaccuracies, and their relationship to participants’ use of out-of-network providers and insurance-related grievances and complaints. We studied mental health directories separately because few psychiatrists participate in private insurance networks, and management of mental health services is separated from that of general medical services in 85 percent of private plans.22 Therefore, the level, consequences, and source of, as well as remedies for, inaccuracies in mental health directories may be different from those in general medical directories.

We asked participants, “In the past 12 months, did you use your insurer’s mental health provider directory?” Those who had used the directory were asked, “In the past 12 months, did you find that in-network mental health providers listed in your insurer’s provider directory?” and were then asked to indicate yes or no for the listed directory problems. Participants were considered to have experienced a directory accuracy problem if they answered yes to any of the four problems studied. We created a second measure that indicated whether the participant had encountered inaccuracies in either contact information or network participation, the two most fundamental directory problems. Directory problems were chosen based on our perception of how troubling the inaccuracy would be to patients and how prevalent and easy to recall it would be.

Participants were asked whether each mental health provider they had seen in the past twelve months was in or out of network. The survey then allowed participants to add a detailed description of their experiences with up to two mental health providers. A participant was considered to have received a “surprise” out-of-network bill if they reported that they first became aware that any provider was out of network at the time of the first scheduled appointment or after that visit (for example, when they received the bill). Participants who did not report any out-of-network mental health use were categorized as not having received a surprise bill.

Participants were asked if they had ever complained to their insurer or a government agency about insurance network issues, and if they responded affirmatively, they were asked to choose the type of complaint filed from a list of four types. Participants were allowed to note more than one complaint type. We created a categorical variable, with participants coded as having reporting the complaint type that we considered the most likely to be considered by regulators (in this order: complained to a government agency, submitted a grievance or complaint form to their insurer, spoke to an insurance company employee on the phone, and other complaint type or refused to answer).

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler 6 scale, with a score of 13 or higher indicating serious psychological distress.23 Demographic information had previously been collected by KnowledgePanel.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

All reported analyses were weighted to match respondents to the US population based on Current Population Survey data in terms of sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, census region, household income, home ownership, and metropolitan area. Weights were also adjusted for panel recruitment, attrition, oversampling, and survey nonresponse. Frequencies were calculated, and to examine relevant associations, we used two-sided chi-square tests that considered p values of 0.05 to be significant. All analyses used Stata, version 15.1.

The Yale Human Investigation Committee and the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study, and participants provided informed consent before initiating the survey.

LIMITATIONS

This study had several limitations. The first was nonresponse bias. Although survey weights accounted for nonresponse, only a limited number of characteristics were considered in constructing the weights, which indicates that additional differences may remain.

The second was recall bias. To mitigate that and other potential biases, we used a short reference period (twelve months) and conducted cognitive interviews to ensure that questions were understandable. Moreover, recall bias would likely lead to a downward bias in our estimates of inaccuracies, although participants who used an out-of-network provider might have been more likely to recall experiencing a directory inaccuracy.

Third, our survey allowed us to document only whether a participant reported experiencing the relevant problem at least once in the past year. We did not know how often they experienced each problem.

Fourth, and perhaps most important, our study design described associations and did not allow us to determine whether the use of more accurate directories would lead to fewer patients being treated by out-of-network specialty mental health providers.

Study Results

From an initial sample of 29,854 panelists ages 18–64, 19,602 completed the screener, which resulted in a survey completion rate of 66 percent, using the standard American Association for Public Opinion Research definition for probability-based internet panels24 (appendix exhibit A2).21 Compared to nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be non-Hispanic whites (74 percent versus 60 percent) and ages 50–64(52 percent versus 37 percent) and to have higher levels of education and household income. After weighting, respondent characteristics were more similar to those of the US population, with the largest remaining difference being 3.5 percentage points in the age distribution (appendix exhibit A3).21 Of the 2,131 qualifying participants who met our inclusion criteria, 861 had used outpatient mental health services in the past twelve months. Of these, 24 had missing information related to use of the directory and were dropped from our analyses. Thus, 837 were included in the analyses.

DIRECTORY USE

Study participants were predominantly young (41 percent were ages 18–34), female (58 percent) and non-Hispanic white (66 percent), and 36 percent reported serious psychological distress. Forty-four percent had used a mental health directory in the past twelve months (exhibit 1). Participants who had used a directory were more likely to have serious psychological distress, compared to those who had not used a directory (41 percent versus 32 percent). No other studied participant characteristics were associated with directory use.

EXHIBIT 1.

Characteristics of the sample, study of the accuracy of health insurers’ mental health provider directories

| Used insurer’s mental health provider directory |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Full sample | Yes (n = 348) | No (n = 489) |

| Used mental health directory In the past 12 months | 44% | 100% | 0% |

| Age, years | |||

| 18–34 | 41 | 43 | 39 |

| 35–49 | 35 | 37 | 33 |

| 50–64 | 25 | 20 | 28 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 58 | 56 | 59 |

| Male | 42 | 44 | 41 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 66 | 62 | 70 |

| Non-Hispanic nonwhite | 17 | 18 | 17 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 20 | 13 |

| Education | |||

| Less than a bachelor’s degree | 55 | 52 | 57 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 45 | 48 | 43 |

| Self-reported health statusa | |||

| Excellent, very good, or good | 87 | 86 | 88 |

| Fair or poor | 13 | 14 | 12 |

| Marketplace planb | |||

| No | 94 | 94 | 93 |

| Yes | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Psychological distress** | |||

| Less than serious or no psychological distress | 64 | 59 | 68 |

| Serious psychological distress | 36 | 41 | 32 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey data from 2018. NOTES Except where otherwise noted, the sample included 837 privately insured English-speaking people in health plans with a provider network who had used outpatient specialty mental health care in the past twelve months. It excluded 24 people with missing data for any relevant outcome question. The sample sizes represent number of (unweighted) survey participants. The percentages were weighted to account for oversampling, survey recruitment, and nonresponse and to match respondents to the US population. Serious psychological distress was defined as a score of 13 or higher on the Kessler 6 scale. Significance was measured by chi-square tests of independence.

822 people.

808 people.

p < 0.05

DIRECTORY INACCURACIES

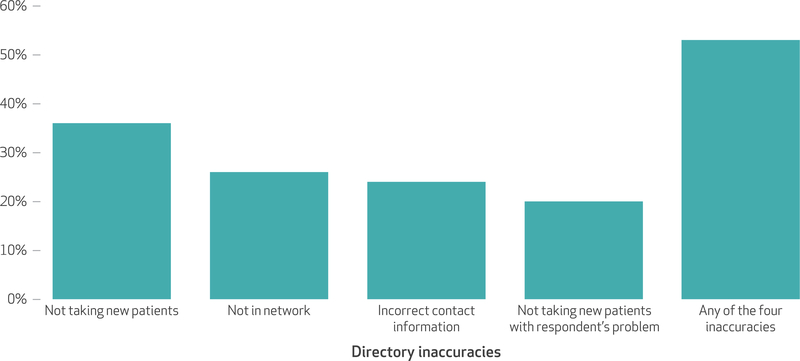

Fifty-three percent of participants who had used a mental health directory reported encountering at least one of the four directory problems in the past twelve months (exhibit 2). The most common problem was that a provider was incorrectly listed as taking new patients (36 percent). Twenty-six percent of participants found that a provider listed in the directory did not accept their insurance. Similarly, 24 percent encountered contact information that was not correct, and 20 percent reported being told that a provider listed as taking new patients was not taking patients with their problem or condition. Thirty-six percent reported encountering inaccuracies in either contact information or network participation, the most fundamental directory items (data not shown).

EXHIBIT 2. Percent of survey respondents who reported directory inaccuracies, by type of inaccuracy, 2018.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey data from 2018. NOTES The sample consisted of 333 privately insured English-speaking people in health plans with a provider network who used both outpatient specialty mental health care and their insurer’s mental health provider directory in the past twelve months. It excluded 15 people with missing data for any relevant outcome question. Respondents could choose more than one inaccuracy. The percentages were weighted, but the sample size noted represents unweighted survey participants.

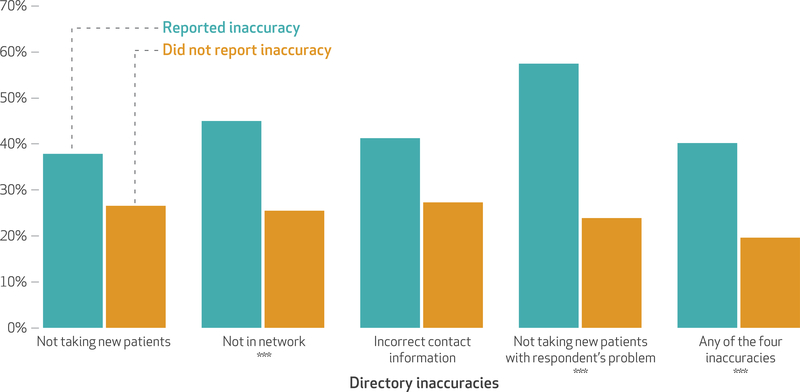

USE OF OUT-OF-NETWORK PROVIDERS

Experiencing inaccuracies with the directory was significantly associated with use of out-of-network providers (exhibit 3). Among participants who encountered any of the four kinds of directory inaccuracies studied, 40 percent were treated by anout-of-network provider in the past year, compared with 20 percent among those who did not encounter directory inaccuracies. Even when we defined inaccuracies more narrowly-considering only those participants who had problems with contact information or network participation—the results were similar (40 percent versus 25 percent; p = 0:03, results not shown).

EXHIBIT 3. Percent of survey respondents who were treated by an out-of-network mental health care provider, by whether or not they reported specific directory inaccuracies, 2018.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of survey data from 2018. NOTES The sample is explained in the notes to exhibit 2. Respondents could choose more than one inaccuracy. The percentages were weighted, but the sample size noted represents unweighted survey participants. Significance refers to unadjusted tests of differences in whether treated by an out-of-network mental health provider. ***p < 0:01

SURPRISE OUTPATIENT BILLS

Among participants who used mental health directories, those who encountered at least one of the directory inaccuracies studied were four times more likely to have a surprise outpatient bill (16 percent versus 4 percent; p = 0:01) (results not shown). This indicates that they did not know they were seeing an out-of-network mental health provider before they arrived at their first scheduled appointment.

REPORTING COMPLAINTS OR GRIEVANCES

Compared to participants who did not encounter an inaccuracy, those who did filed complaints at higher rates (28 percent versus 4 percent) (exhibit 4). However, among those who encounatered inaccuracies, only 3 percent reported that they had filed a complaint with a government agency. An additional 9 percent said that they had submitted a grievance or complaint form to their insurer, and 16 percent reported that they had only complained to an insurance company employee by phone.

EXHIBIT 4.

Percent of survey respondents who complained about a problem related to their insurer’s mental health network, among participants who used the insurer’s mental health provider directory

| Reported directory inaccuracy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample (N = 333) | Yes (n = 192) | No (n = 141) | |

| Made any complaint | 17% | 28% | 4% |

| Made a complaint (by method) | |||

| Made a complaint to a government agency | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Sent a complaint form to insurer | 5 | 9 | 0 |

| Spoke to an insurance company employee | 9 | 16 | 1 |

| Other or refused to answer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Made no complaint | 83 | 72 | 96 |

source Authors’ analysis of survey data from 2018. notes The sample included privately insured English-speaking people in health plans with a provider network who had used outpatient specialty mental health care in the past twelve months and used their insurer directory in the past year. The percentages were weighted, but the sample size noted represents unweighted survey participants. Respondents were defined as having made any complaint if they answered yes to the following question: “In the past 12 months, have you complained to your insurance company or a government agency (for example, the state insurance commission) about lack of availability of in-network mental health providers, payments related to out-of-network mental health care, or other problems related to your insurer’s mental health provider network?” An unadjusted test of differences in whether participants experiencing an inaccuracy noted any complaint had a p value of <0.001. Respondents who answered yes were asked to choose one or more method of complaint from a list of four types. The method of complaint is recoded to be mutually exclusive by assigning participants to the complaint method noted most likely to be considered by regulators (that is, in the order listed in the exhibit).

Discussion

This study builds on previous literature that found incorrect information in psychiatrist information in mental health provider directories by including nonpsychiatrist providers and examining patient experiences. First, our consumer-centric focus allowed us to analyze the accuracy of listings of mental health providers whom patients attempted to contact, rather than overall directory accuracy—which improves the usefulness of our findings.25 Second, we believe that we are the first to document the possible consequences of inaccuracies, finding an association between encountering incorrect listings and the use of out-of-network providers and receipt of surprise outpatient bills. Finally, most prior work has focused on the Affordable Care Act’s Marketplace plans, while our survey included patients enrolled in non-Marketplace commercial plans, which arguably are the plans with the greatest resources available to update directories.

Almost half of privately insured patients who received outpatient mental health services used mental health directories, with significantly higher use among people with serious psychological distress. Given the exceptionally low rates of engagement found in studies of other insurance plan tools, such as price transparency websites, this is particularly remarkable.26 Accurate directories have the potential to be a useful tool for matching patients with mental health providers who meet their needs and preferences. Directories that provide accurate information on whether a clinician specializes in specific populations (such as children or veterans), speaks languages other than English, or provides relevant social services have the potential to improve the quality of initial patient-provider matches.Yet even when we considered only contact information and network participation—the most fundamental directory informa-tion—we found that 36 percent of participants reported encountering inaccuracies.

Directory inaccuracies might not be without consequence: Participants who encountered inaccuracies were twice as likely to have used at least one out-of-network mental health provider in the past year. That 16 percent of patients who reported encountering inaccuracies also indicated that they had received a surprise bill suggests that inaccuracies may lead some patients to mistakenly go out of network.

Interestingly, even among participants who did not report any inaccuracies, one in five used an out-of-network mental health provider. This suggests that there are multiple reasons for high out-of-network use in mental health, including the desire to maintain continuity with a provider who is no longer in network or the belief that an out-of-network provider is of higher quality. A prior survey that investigated reasons for out-of-network provider use found that respondents were more likely to note the recommendation of another doctor, a family member, or friends when asked about mental health care compared to general medical care (26 percent versus 13 percent).6

Associations between directory inaccuracy and use of out-of-network care may also be indicative of mental health network inadequacy, which is a problem since psychiatrists are less likely than other physicians to participate in private insurer networks.1,27 There is evidence that insurer mental health networks are more restrictive than general medical networks, at least in Marketplace plans.28 Inthe face of an inadequate network, even if a patient knowingly “chooses” to go out of network, their decision may be influenced by a lack of timely access to high-quality in-network providers. Advocates and news reports have used the term “ghost” or “phantom” network to describe providers listed in directories who are unreachable or not taking new patients.29

To assess whether insurers have provided patients with sufficient in-network providers, states rely on a variety of network adequacy measures, ranging from geographic access, provider-to-enrollee ratios, and timely access standards.9 In turn, many of these measures rely on directory data. The significant accuracy issues found in this study bring into question the ability of regulators to judge whether a plan’s network is adequate. If regulators or researchers rely on inaccurate information, network adequacy may be more of a problem than previously reported.

Adequate regulation of networks may be particularly important in mental health care. Even with risk adjustment, plans may benefit from dissuading people with high-cost chronic mental health conditions from enrolling.30 In the past, plans may have used differential cost sharing, strict prior authorization rules, and other benefit design characteristics to do so. Under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, these tools are less available to plans. Network composition is significantly more difficult to regulate.31 Having an inadequate network or excluding mental health providers who treat particularly high-cost patients makes plans less attractive to people who expect to need these services.

If directory data are so critical to evaluating network adequacy, why are inaccuracies so common? The dynamic nature of provider data (including multiple office locations and frequent changes in network participation), resource limitations, lack of provider engagement, inconsistent standards across states and plan types, and infrequent state plan credentialing have been noted as possible causes of directory inaccuracies.32,33 Another challenge is that compared to providers in other special ties, mental health providers are more likely to be solo practitioners27 and thus may lack ancillary staff to aid insurers with updating and validating directory listings.

Federal rules require Medicaid managed care, Medicare Advantage, and Marketplace plans to provide accurate up-to-date directories, but there are currently no federal protections for the majority of US residents with other commercial insurance.34 A recent Senate bill included requirements that private plans maintain accurate directories.35 Approximately twenty states have requirements directly related to directory accuracy for private plans, though these state laws vary in how often directories must be updated, the types of plans covered (for example, health maintenance organizations and preferred provider organizations), and the content required.36,37 In addition, self-insured plans may be exempt from these state laws under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, and prior work suggests that the state laws are not strictly enforced.38 Other proposals to improve accuracy include requiring insurers to verify networks with external data sources and requiring that directories be maintained in a machine-readable format.33

While complaints can help patients obtain resolution case by case, they have an additional population-level benefit in aiding regulators to uncover problems that are difficult to identify.39 After initial accreditation, most states rely on consumer complaints to assess network adequacy.16,17 While 28 percent of participants who encountered inaccuracies reported making a complaint, the most common method was a phone call to an insurer. It is difficult to assess how these complaints are categorized by insurers and whether they are reliably included in reports provided to states. This finding suggests that regulators should make consumers aware of their ability to file complaints with state departments of insurance and the mechanisms used to do so. States should also consider employing additional monitoring tools, such as patient surveys, audits, and comparisons to external data sources.

Networks serve a useful purpose in that they provide leverage for plans to negotiate favorable reimbursement rates with providers and allow plans to steer patients to high-quality clinicians and facilities.40 For example, greater Marketplace plan network breadth has been shown to be associated with higher premiums41 and is likely why so-called narrow-network plans are common in state Marketplaces. While patient protections are needed, these protections should be balanced against potential costs.42 Yet we found that even the most fundamental information necessary for a well-functioning market that serves patients—that is, contact information of participating providers—might not be available to patients. While mental health provider shortages may make it difficult for plans to maintain mental health networks that meet network adequacy requirements, accurate directory information seems fundamental to the most basic level of patient engagement and access.

Conclusion

Although mental health provider directories are widely used, inaccuracies are a pervasive problem and are associated with receiving out-of-network care and outpatient surprise bills. Compared to providers in other specialties, fewer mental providers participate in commercial networks—which suggests that the ability to measure network adequacy may be particularly important. A federal standard for directory accuracy, stronger enforcement of existing laws with insurers liable for directory errors, and additional monitoring by regulators may be needed.

Supplementary Material

The significant accuracy issues found in this study bring into question the ability of regulators to judge whether a plan’s network is adequate.

Accurate directory information seems fundamental to the most basic level of patient engagement and access.

Acknowledgments

The findings of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Washington, D.C., May 10, 2019. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. R21MH109783). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Susan H. Busch, Department of Health Policy and Management, Yale School of Public Health, in New Haven, Connecticut.

Kelly A. Kyanko, Department of Population Health, New York University Langone Health, in New York City.

NOTES

- 1.Busch SH, Ndumele CD, Loveridge CF, Kyanko KA. Patient characteristics and treatment patterns among psychiatrists who do not accept private insurance. Psychiatr Serv. 2019; 70(1):35–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mark TL, Olesiuk W, Ali MM, Sherman LJ, Mutter R, Teich JL. Differential reimbursement of psychiatric services by psychiatrists and other medical providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(3):281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melek SP, Perlman D, Davenport S. Addiction and mental health vs. physical health: analyzing disparities in network use and provider reimbursement rates [Internet] Seattle (WA): Milliman; 2017. December [cited 2020 Mar 24]. (Milliman Research Report). Available from: https://milliman-cdn.azureedge.net/-/media/milliman/importedfiles/uploadedfiles/insight/2017/nqtldisparityanalysis.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelech D, Hayford T. Medicare Advantage and commercial prices for mental health services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(2):262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, Ross JS. Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined, 2003–13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(7):1271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. Out-of-network provider use more likely in mental health than general health care among privately insured. Med Care. 2013;51(8):699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. Surprise billing: no surprise in view of network complexity. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet] 2019. June 5 [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190603.704918/full/

- 8.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. A knotty problem: consumer access and the regulation of provider networks. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2019;44(6):937–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wishner JB, Marks J. Ensuring compliance with network adequacy standards: lessons from four states [Internet]. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2017. March [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88946/2001184-ensuring-compliance-with-network-adequacy-standards-lessons-from-four-states_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blech B,West JC,Yang Z, Barber KD, Wang P, Coyle C. Availability of network psychiatrists among the largest health insurance carriers in Washington, D.C. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68(9):962–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cama S, Malowney M, Smith AJB, Spottswood M, Cheng E, Ostrowsky L, et al. Availability of outpatient mental health care by pediatricians and child psychiatrists in five U.S. cities. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(4): 621–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malowney M, Keltz S, Fischer D, Boyd JW. Availability of outpatient care from psychiatrists: a simulated-patient study in three U.S. cities. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66(1):94–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mental Health Association in New Jersey. MHANJ’s network adequacy study [Internet]. Springfield (NJ): MHANJ; 2013. July [cited 2020 Apr 24]. Available for download from: https://www.mhanj.org/2017/12/13/mhanjs-network-adequa-cy-study/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mental Health Association of Maryland. Access to psychiatrists in 2014 qualified health plans [Internet]. Lutherville (MD): MHAMD; 2015. January 26 [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.mhamd.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/2014-QHP-Psychiatric-Network-Adequacy-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olfson M, Wang S, Wall M, Marcus SC, Blanco C. Trends in serious psychological distress and outpatient mental health care of US adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019; 76(2):152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall MA, Ginsburg PB. A better approach to regulating provider network adequacy [Internet]. Washington (DC): Brookings Institution; 2017. September [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/regulatory-options-for-provider-network-adequacy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber C, Bridgeland B, Burns B, Corlette S, Gmeiner K, Herman M, et al. Ensuring consumers’ access to care: network adequacy state insurance survey findings and recommendations for regulatory reforms in a changing insurance market [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Association of Insurance Commissioners; 2014. November [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.naic.org/documents/committees_conliaison_network_adequacy_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ipsos. KnowledgePanel overview [Internet]. New York (NY): Ipsos; [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/18-11-53_Overview_v3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Singer S, Wagner TH. Validity of the survey of health and internet and Knowledge-Network’s panel and sampling Stanford (CA): Stanford University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 22.Horgan CM, Stewart MT, Reif S, Garnick DW, Hodgkin D, Merrick EL, et al. Behavioral health services in the changing landscape of private health plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2016; 67(6):622–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2): 184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys [Internet] Washington (DC): AAPOR; 2016. [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haeder SF, Weimer D, Mukamel DB. A consumer-centric approach to network adequacy: access to four specialties in California’s Marketplace. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(11):1918–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Examining a health care price transparency tool: who uses it, and how they shop for care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(4):662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2): 176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu JM, Zhang Y, Polsky D. Networks in ACA Marketplaces are narrower for mental health care than for primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(9):1624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holstein R, Paul DP 3rd. “Phantom networks” of managed behavioral health providers: an empirical study of their existence and effect on patients in two New Jersey counties. Hosp Top. 2012;90(3):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montz E, Layton T, Busch AB, Ellis RP, Rose S, McGuire TG. Risk-adjustment simulation: plans may have incentives to distort mental health and substance use coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(6): 1022–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuire TG. Achieving mental health care parity might require changes in payments and competition. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016; 35(6):1029–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.America’s Health Insurance Plans. Provider directory initiative key findings [Internet] Washington (DC): AHIP; 2017. March [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ProviderDirectory_IssueBrief_3.7.17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adelberg M, Frakt A, Polsky D, Strollo MK. Improving provider directory accuracy: can machine-readable directories help? Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(5):241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Information requirements: 42 C.F.R. Sect. 438.10(h)(1) (2012). Disclosure requirements: 42 C.F.R. Sect. 422.111 (2011). Network adequacy standards: 45 C.F.R. Sect. 156.230 (2016).

- 35.S. 1895: to lower health care costs [Internet] Washington (DC): US Senate; 2019. July 8 [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116s1895rs/pdf/BILLS-116s1895rs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoyt B. Provider directories: litigation, regulatory, and operational challenges Emeryville (CA): Berkeley Research Group; 2015. March 19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giovannelli J, Lucia KW, Corlette S. Implementing the Affordable Care Act: state regulation of Marketplace plan provider networks. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2015;10:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. Secret shoppers find access to providers and network accuracy lacking for those in Marketplace and commercial plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(7):1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillespie A, Reader TW. Patient centered insights: using health care complaints to reveal hot spots and blind spots in quality and safety. Milbank Q. 2018;96(3):530–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard DH. Adverse effects of prohibiting narrow provider networks. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polsky D, Cidav Z, Swanson A. Marketplace plans with narrow physician networks feature lower monthly premiums than plans with larger networks. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(10):1842–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall MA, Adler L, Ginsburg PB, Trish E. Reducing unfair out-of-network billing—integrated approaches to protecting patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):610–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.