Abstract

Background

Combined pulmonary fibrosis with emphysema (CPFE) is a clinically meaningful syndrome characterized by coexisting upper-lobe emphysema and lower-lobe interstitial fibrosis. However, ambiguous diagnostic criteria and, particularly, the absence of objective methods to quantify emphysematous/fibrotic lesions in patients with CPFE confound the interpretation of the pathophysiology of this syndrome. We analyzed the relationship between objectively quantified computed tomography (CT) measurements and the results of pulmonary function testing (PFT) and clinical events in CPFE patients.

Materials and methods

We enrolled 46 CPFE patients who underwent CT and PFT. The extent of emphysematous lesions was obtained by calculating the percent of low attenuation area (%LAA). The extent of fibrotic lesions was calculated as the percent of high attenuation area (%HAA). %LAA and %HAA values were combined to yield the percent of abnormal area (%AA). We assessed the relationships between CT parameters and other clinical indices, including PFT results. Multivariate analysis was performed to examine the association between the CT parameters and clinical events.

Results

A greater negative correlation with percent predicted diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO %predicted) existed for %AA (r = -0.73, p < 0.001) than for %LAA or %HAA alone. The %HAA value was inversely correlated with percent predicted forced vital capacity (r = -0.48, p < 0.001), percent predicted total lung capacity (r = -0.48, p < 0.01), and DLCO %predicted (r = -0.47, p < 0.01). Multivariate logistic regression analysis found that %AA showed the strongest association with hospitalization events (odds ratio = 1.20, 95% confidence interval = 1.01–1.54, p = 0.029).

Conclusion

Quantitative CT measurements reflected deterioration in pulmonary function and were associated with hospitalization in patients with CPFE. This approach could serve as a useful method to determine the extent of lung morphology, pathophysiology, and the clinical course of patients with CPFE.

Background

Combined pulmonary fibrosis with emphysema (CPFE) is characterized by the coexistence of upper-lobe emphysema and lower-lobe fibrosis. Cottin et al. proposed the term “CPFE” for the entity characterized by these radiological features, a preserved lung volume, and severely diminished capacity for gas exchange [1]. The coexistence of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis in individual patients is not rare in clinical practice. The estimated prevalence of pulmonary fibrosis is 8% in patients with stage 2 or higher chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [2], and approximately 30% of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) show manifestations of emphysema on chest computed tomography (CT) [3]. CPFE usually develops in men who are commonly older than 60 years of age and are current or ex-smokers, which is similar to the epidemiology of IPF [4, 5]. Follow-up studies have found that the prognosis of patients with CPFE is very poor, because of complications such as severe pulmonary hypertension, lung cancer, and acute exacerbations (AEs) [3, 6–8].

Patients with CPFE show severely reduced diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), mild airflow limitation, and preserved lung capacity [9]. The baseline value for percent predicted DLCO (DLCO %predicted) is lower in patients with CPFE than in patients with COPD without pulmonary fibrosis [10] or in patients with IPF alone [11]. The respective annual decreases in vital capacity (VC) and DLCO were significantly smaller and larger in patients with CPFE than in patients with IPF [11]. The findings on pulmonary function testing (PFT) of CPFE patients are the results of additive effects or the counterbalance between the restrictive effects of pulmonary fibrosis and the hyperinflation associated with emphysematous lesions [9].

On the other hand, for patients with CPFE, several studies have reported on the correlations between radiological morphological findings and pulmonary function [12, 13]. Subjective visual assessments of emphysematous/fibrotic lesions on radiological imaging have been commonly performed. However, objective quantitative assessments are needed to clarify the relationships between morphological findings and the physiological characteristics of the disease, and to allow reproducible and longitudinal multicenter studies. A few recent studies used multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) to perform simultaneous objective quantitative assessments of the extent of emphysema and fibrosis in patients with CPFE and determined the association between the morphological findings and pulmonary dysfunction [14, 15]. However, whether these objective assessments are associated with the clinical manifestations of patients with CPFE has not been established.

Thus, the aims of this study were as follows: first, to evaluate the correlations between PFT results, including DLCO, and the extent of emphysematous/fibrotic lesions as reflected by quantitative CT measurements; and second, to assess these CT measurements in relation to the factors associated with clinical events in patients with CPFE.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study protocol conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of our university (approval numbers: 857 and 2083), and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

We enrolled 113 patients who presented to our hospital between July 2012 and August 2018 for CPFE management. CPFE was diagnosed according to CT criteria described by Cottin et al., as follows: 1) the presence of a predominantly upper lobe emphysema, defined as well-demarcated areas of decreased attenuation, marginated by a very thin (< 1 mm) or no wall, and/or multiple bullae (> 1 cm); and 2) the presence of predominantly peripheral and basal pulmonary fibrosis, defined as reticular opacities and traction bronchiectasis with or without honeycombing [1]. Emphysema was classified into the following 3 groups: centrilobular, paraseptal, and mixed type (centrilobular plus paraseptal) emphysema. The patterns of pulmonary fibrosis were classified according to the IPF guidelines into usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), probable UIP, indeterminate for UIP, and alternative-diagnosis pattern [5]. The classification of the patterns of pulmonary emphysema and fibrosis were performed independently by 3 clinical pulmonologists (MS, NK, and JI) who were blinded to the clinical information of the study patients.

We finally enrolled 46 patients with CPFE (Fig 1) after eliminating those with the following exclusion criteria: 1) lung cancer (n = 24); 2) connective tissue disease (n = 18); 3) systemic glucocorticoid treatment (n = 4); 4) infectious disease, including mycobacterial disease and aspergillosis (n = 3); 5) thoracic surgery (n = 2); 6) chemotherapy (n = 2); 7) heart failure (n = 0); and 8) others (n = 14).

Fig 1. Study population.

A total of 46 patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis with emphysema were included. Abbreviations: CPFE, combined pulmonary fibrosis with emphysema; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SjS, Sjögren syndrome; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis.

MDCT examinations

All patients underwent 64-MDCT (Aquilion ONE and Aquilion PRIME; Canon Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) and were scanned from the thoracic inlet to the diaphragm during full inspiration without contrast enhancement. The MDCT scan parameters were as follows: collimination, 0.5 mm; 120 kV; auto-exposure control; gantry rotation time, 0.5 second; and beam pitch, 0.83. All images were reconstructed by standard algorithms (FC07) with a slice thickness of 0.5 mm and a reconstruction interval of 0.5 mm. The voxel size was 0.63 × 0.63 × 0.5 mm.

Quantitative CT measurements

We selected 4 CT slices from each CT series as follows: the first upper lung slice was taken 1 cm above the upper margin of the aortic arch (upper lesion), the second upper lung slice was taken at the carina (middle lesion), the first lower lung slice was taken 1 cm below the right inferior pulmonary vein (lower lesion), and the second lower lung slice was taken at the lower edge of the heart (bottom lesion). High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) images were analyzed by an image-processing program (ImageJ, version 1.51j8, available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

The quantitative measurements were performed in accordance with Matsuoka et al. [14, 16]. We used a threshold technique to segment all the pixels between -200 and -1024 Hounsfield units (HU) as the total lung area (TLA). To determine the extent of emphysema, we segmented pixels lower than -950 HU as the low attenuation area (LAA; Fig 2A and 2B), and %LAA was calculated for each slice as the percent of LAA relative to TLA. Similarly, to determine the extent of interstitial fibrotic lesions, we segmented all the pixels greater than -700 HU as the high attenuation area (HAA; Fig 2C and 2D); and %HAA was calculated for each slice as the percent of HAA relative to TLA. To calculate the total area of emphysematous and fibrotic changes, the percent of abnormal area (%AA) was obtained by summing the values for %LAA and %HAA at each thoracic level. The %LAA, %HAA, and %AA were calculated as the mean values of %LAA, %HAA, and %AA in each CT slice, respectively. These data were confirmed independently by 2 pulmonologists (MS and NK). All data were anonymized, and the observers were blinded to other characteristics of the participants when the imaging analysis was performed.

Fig 2.

Axial computed tomography (CT) images of the upper (a) and lower lungs (c). Pixels with attenuation values between -950 and -1024 Hounsfield units (HUs) (b) and greater than -700 HUs (d) are highlighted in black on the CT scans.

Pulmonary function testing

All study participants underwent PFT by a CHSTAC-8900 spirometer (Chest MI, Tokyo, Japan). PFT was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society [17]. Total lung volume was determined by the helium dilution method, and DLCO and alveolar ventilation were determined by the single-breath method. The values for percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1%predicted) were calculated according to the equations of the Japanese Respiratory Society [18].

Clinical events

We investigated clinical events (hospitalizations, AEs, and deaths) during the observation period. The diagnosis of AEs was based on the AE criteria for IPF, as follows [19]: 1) acute worsening or development of dyspnea, typically < 1 month duration, 2) new bilateral ground-glass opacity and/or consolidation on CT, and 3) deterioration not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. In addition, duration of follow-up, smoking history, and serum levels of Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) were determined.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (± SD) or as medians (interquartile range [IQR]) as appropriate. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were determined to assess the intra- and interobserver reliability of CT measurements. After confirmation of the normality of the data on study parameters, the correlations between CT measurements and the results of PFT were assessed by Spearman rank correlation analysis, as appropriate. Comparisons between the group of patients with and without hospitalization events were performed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to identify which variables were associated with hospitalization events. The variables that were significant in the univariate model were then entered into a multivariate regression analysis to identify the independent determinants of hospitalization events. For all analyses, the null hypothesis was rejected at the 5% level. Statistical analysis was performed by JMP 13.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

The general characteristics of the 46 enrolled CPFE patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 67.2 ± 7.8 years, and the 97.8% of patients were males. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.0 ± 3.7 kg/m2. Except for 1 participant, all patients had a smoking history, and a mean of 62.0 ± 41.2 pack-years. The mean duration of follow-up was 1,087.9 ± 574.5 days.

Table 1. Patient characteristics, pulmonary function tests, and computed tomography measurements.

| Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.2 ± 7.8 |

| Male/female, n (%) | 45 (97.8%)/1 (2.2%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.7 |

| Pack years | 62.0 ± 41.2 |

| Smoker (Current or ever/never) | 45 (97.8%)/1 (2.2%) |

| Follow-up duration (days) | 1087.9 ± 574.5 |

| KL-6 (U/mL) | 1038.8 ± 1041.0 |

| Pulmonary function tests | |

| FVC (L) | 3.1 ± 0.8 |

| FVC %predicted (%) | 86.7 ± 20.3 |

| FEV1%predicted (%) | 81.8 ± 18.3 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 77.9 ± 9.3 |

| FRC %predicted (%) | 81.8 ± 16.6 |

| RV %predicted (%) | 83.3 ± 21.2 |

| TLC (L) | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

| TLC %predicted (%) | 84.3 ± 15.9 |

| DLCO (mL/min/mmHg) | 11.7 ± 4.6 |

| DLCO %predicted (%) | 65.4 ± 23.3 |

| CT measurements | |

| Emphysema type (centrilobular/paraseptal/mixed type) | 21/17/8 |

| Fibrosis type (UIP/probable UIP/indeterminate for UIP/alternative diagnosis pattern) | 15/19/10/2 |

| %LAA (median [IQR]) (%) | 4.9 (1.9–8.5) |

| %HAA (median [IQR]) (%) | 20.2 (15.4–25.6) |

| %AA (median [IQR]) (%) | 25.5 (21.0–36.2) |

| Clinical events | |

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 8 (17.4%) |

| Acute exacerbation, n (%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Death, n (%) | 3 (6.5%) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen-6; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FRC, functional residual capacity; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; %LAA, percent of low attenuation area to total lung area; %HAA, percent of high attenuation area to total lung area; %AA, percent of abnormal area to total lung area.

PFT and CT measurements

The results of PFT and quantitative CT measurements are presented in Table 1. The mean percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC %predicted), the mean FEV1%predicted, the mean percent predicted total lung capacity (TLC %predicted), and the mean DLCO %predicted were 86.7 ± 20.3%, 81.8 ± 18.3%, 84.3 ± 15.9%, and 65.4 ± 23.3%, respectively.

Study participants were classified by emphysema type as centrilobular (n = 21), paraseptal (n = 17), and mixed (n = 8) type. Regarding the pattern of pulmonary fibrosis, the patients were categorized as UIP (n = 15), probable UIP (n = 19), indeterminate for UIP pattern (n = 10), and alternative diagnosis (n = 2).

The median (IQR) %LAA, %HAA, and %AA were 4.9% (1.9–8.5%), 20.2% (15.4–25.6%), and 25.5% (21.0–36.2%), respectively. The CT measurements showed excellent reproducibility. The ICC for intraobserver variability among the CT parameters were as follows: %LAA, 0.998 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.997–0.999); %HAA, 0.998 (0.996–0.999); %AA, 0.998 (0.996–0.999). The ICC between 2 observers (interobserver variability) for the CT parameters were as follows: %LAA, 0.971 (95% CI, 0.948–0.984); %HAA, 0.994 (0.989–0.997); %AA, 0.984 (0.971–0.991).

The correlations between the CT measurements and the results of PFT are shown in Table 2. The %AA parameter was more negatively correlated with DLCO %predicted (r = -0.73, p < 0.001) than %LAA (r = -0.51, p < 0.001) or %HAA (r = -0.47, p < 0.01) alone. The %AA parameter was also significantly correlated with FVC %predicted, FEV1%predicted, and TLC %predicted. The %HAA parameter was inversely correlated with FVC %predicted, FEV1/FVC, TLC %predicted, and DLCO %predicted. In contrast, no significant correlations between %LAA and the results of PFT existed, except DLCO %predicted. Fig 3 demonstrates the correlations between DLCO %predicted and CT measurements on a two-dimensional analysis plot.

Table 2. Correlations between computed tomography measurements and results of pulmonary function tests.

| %LAA | %HAA | %AA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p value | r | p value | r | p value | |

| FVC %predicted | -0.06 | 0.69 | -0.48 | < 0.001 | -0.46 | < 0.01 |

| FEV1%predicted | -0.29 | 0.05 | -0.29 | 0.05 | -0.45 | < 0.01 |

| FEV1/FVC | -0.23 | 0.12 | 0.29 | < 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.41 |

| FRC %predicted | 0.11 | 0.49 | -0.41 | < 0.01 | -0.30 | 0.06 |

| RV %predicted | 0.2 | 0.22 | -0.5 | < 0.01 | -0.27 | 0.10 |

| TLC %predicted | -0.02 | 0.89 | -0.48 | < 0.01 | -0.46 | < 0.01 |

| DLCO %predicted | -0.51 | < 0.001 | -0.47 | < 0.01 | -0.73 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: %LAA, percent of low attenuation area to total lung area; %HAA, percent of high attenuation area to total lung area; %AA, percent of abnormal area to total lung area; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FRC, functional residual capacity; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

Fig 3. Correlations of percent predicted diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide with the percent of low attenuation area, the percent of high attenuation area, and the percent of abnormal area.

Abbreviations: DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; %LAA, percent of low attenuation area; %HAA, percent of high attenuation area; %AA, percent of abnormal area.

Clinical events

Table 1 also shows a summary of the clinical events. Three patients died of AE of IPF, chronic respiratory dysfunction, or heart failure. Two patients developed an AE. They received systemic corticosteroids and noninvasive oxygenation therapy; 1 patient died and the other recovered. Eight patients were hospitalized for the following reasons: bacterial pneumonia (n = 2), heart failure due to an old myocardial infarction (n = 2), AEs of IPF (n = 2), pneumothorax (n = 1), and other (n = 1). The difference between the duration of follow-up for the participants with or without hospitalization was not significant (median duration 1187 days [627–2373 days] vs 1082 days [21–2255 days]; p = 0.27) (S1 Appendix).

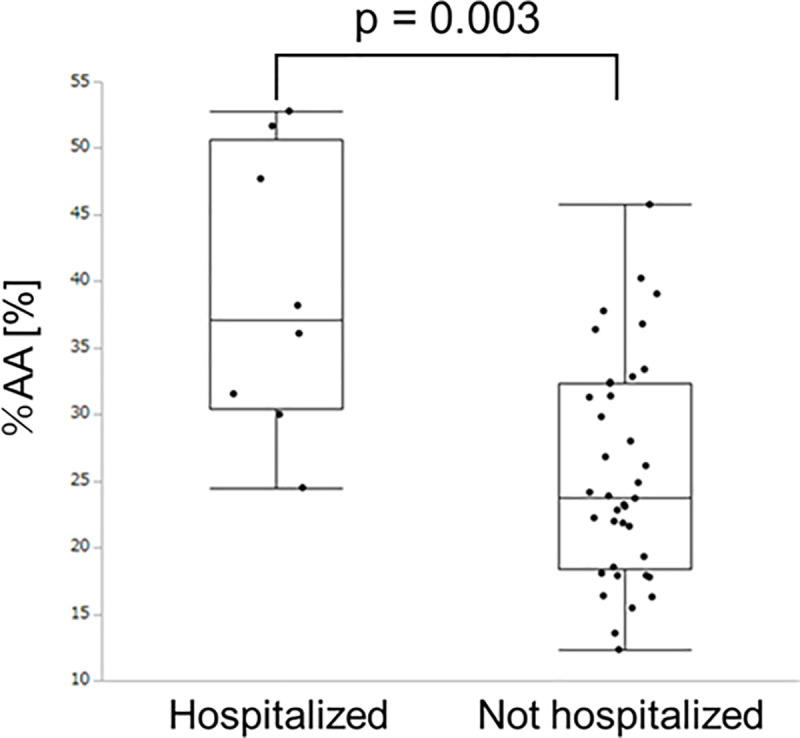

Clinical events and CT measurements

The hospitalization events were related to the parameter, %AA (Fig 4). The results of univariate and multivariate analysis for clinical events are shown in Table 3. The univariate analysis showed that pack-years (odds ratio [OR] = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.93–0.99, p = 0.035), DLCO %predicted (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.82–0.96, p = 0.0006), and %AA (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.06–1.32, p = 0.0005) were significantly associated with hospitalization. Multivariate analysis identified %AA as the only independent factor associated with hospitalization (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.01–1.54, p = 0.029).

Fig 4. Comparison of the percents of abnormal lung areas in participants with vs those without hospitalization.

Abbreviation: %AA, percent of abnormal area.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for hospitalization events.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) | 0.95 | ||

| BMI | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 0.33 | ||

| Pack years | 0.97 (0.93–0.99) | 0.035 | 0.97 (0.90–1.01) | 0.1733 |

| FVC %predicted | 1.07 (0.41–2.99) | 0.89 | ||

| DLCO %predicted | 0.91 (0.82–0.96) | 0.0006 | 0.96 (0.86–1.04) | 0.3629 |

| %AA | 1.16 (1.06–1.32) | 0.0005 | 1.20 (1.01–1.54) | 0.0290 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; FVC, forced vital capacity; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; %AA, percent of abnormal area to total lung area.

Discussion

The key points of this study are as follows: first, the objective quantified CT values for emphysematous LAA and fibrotic HAA were significantly correlated with evidence of impaired pulmonary function; second, the radiological parameters obtained by MDCT were associated with the clinical course of patients with CPFE.

Although previous studies have demonstrated an association between radiological assessments and pulmonary function in patients with CPFE [12, 13, 20], the objective quantitative methods used for determining the simultaneous extents of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis have not been fully explored. However, recent studies on quantitative assessment defined the LAA associated with emphysematous lesions as the regions of lung density that are lower than the threshold of -950 HU, and the HAA associated with fibrotic lesions as the regions of lung density that are higher than the threshold of -700 HU [14–16]. Here, we used those CT criteria and confirmed that the CT parameters were significantly correlated with the results of PFT. These data suggest that this quantitative method may be reproducible and might enable us to perform an objective evaluation of abnormal CT findings.

Among the relationships between CT parameters and PFT results, the abnormal area (%AA), which was defined as the sum of %LAA and %HAA, had a greater correlation with a decrease in DLCO %predicted than %LAA or %HAA alone. The DLCO value is one of the most clinically valuable measurements based on the ability of the lungs to transfer gas from inhaled air to the red blood cells [21]. Although most PFT parameters of patients with CPFE have presented various patterns in accordance with specific morphological changes, a severely reduced DLCO value has been seen to be the most common abnormal finding [8, 9]. A decrease in the DLCO value of patients with CPFE is believed to be associated with alveolar destruction, loss of the pulmonary vascular bed, and alveolar wall thickening/collapse due to both emphysema and fibrotic changes [4]. Thus, the additive effect of emphysematous lesions and pulmonary fibrosis in the lungs of CPFE patients might account for the fact that %AA was more strongly associated with a decreased DLCO %predicted value than %LAA or %HAA alone. Additionally, in patients with IPF, decreased DLCO has been correlated with decreased exercise tolerance, including distance obtained during the 6-minute-walk test [22]. Our results indicate that chest CT assessments might reflect pulmonary physiological dysfunction in patients with CPFE as well as in those with IPF.

In addition, %LAA was only correlated with DLCO %predicted, and tended to be associated with the severity of the obstructive impairment. Although a number of studies of patients with COPD have reported on the relationship between LAA and obstructive impairment [23], only a few reports have described the relationship between LAA and pulmonary dysfunctions in CPFE patients [12, 14]. They reported a correlation between %LAA and decreased FEV1%predicted and between %LAA in the upper lung slice and a decline in DLCO %predicted [12, 14]. In patients with CPFE, the increased traction caused by pulmonary fibrosis prevents collapse of the expiratory airway and expiratory airflow limitation, which are associated with emphysema. Therefore, these patients show a preserved FEV1, FRC %predicted, and RV %predicted [4, 9]. Meanwhile, our study showed that %HAA was more strongly correlated with FRC %predicted and RV %predicted than %LAA. Thus, we consider that the extent of emphysema affects the pulmonary function of patients with CPFE less than their fibrotic lesions affect pulmonary function.

Emphysema subtypes are divided into three types; centrilobular, paraseptal, and panlobular [24]. Centrilobular emphysema is commonly complicated by COPD [25], and emphysema subtypes in COPD are related to pulmonary symptoms, the development of lung cancer, and worsening radiological findings [26, 27]. In contrast, CPFE patients are likely to exhibit paraseptal emphysema (30%-65%) [28, 29], which is consistent with the present study. CPFE with paraseptal emphysema lesions is associated with CTD and a poor prognosis [30–32]. Considering emphysema subtypes in CPFE might contribute to the putative clinical course.

Another notable result of this study concerns our investigation of the relationship between objective quantitative CT measurements and the clinical events of patients with CPFE. Only the parameter %AA was significantly independently associated with hospitalization events on multivariate regression analysis of such clinical factors as age, BMI, pack-years, FVC %predicted, DLCO %predicted, and %AA. Respiratory-related hospitalizations have prognostic significance for patients with COPD and IPF [33–35] and are independently associated with decreased FVC in patients with IPF [34]. A previous report has described the relationship between the radiological assessments and clinical events in CPFE [13]. This study used a subjective assessment of CT images that was based on a fibrosis-weighted CT index, and demonstrated a correlation with the outcome in CPFE patients. In our study, we used a simple automated analysis of CT images, and found a significant relationship between %AA and hospitalization. Our results suggest that this radiological assessment might reflect disease severity and have prognostic value for patients with CPFE.

Interestingly, in our study population, the %AA parameter was more relevant to hospitalization than the DLCO %predicted value. Although reduced DLCO is commonly observed in patients with CPFE, the impact of DLCO on outcome has not been clarified. In patients with IPF, not only gender, age, physiological stage, and composite physical index, but also a decrease from baseline DLCO %predicted, are known to be significant predictors of mortality [36]. A decrease in DLCO is also a predictor of exercise intolerance in patients with COPD [37, 38]. Previous studies have reported on the association between radiological assessments and clinical manifestations in IPF and COPD. In IPF patients with stable or exacerbated disease, the extent of fibrotic changes such as reticulation, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis has been reported to be a significant predictor for the risk of exacerbation and mortality [39, 40]. Similarly, the extent of emphysematous lung predicts the risk of exacerbation and mortality in patients with COPD [41, 42]. For our CPFE patients, we evaluated the %AA parameter that reflects both emphysematous and fibrotic lesions and found that %AA was an independent predictor for hospitalization.

The reasons for the hospitalization of our study patients varied; almost all hospitalizations were for respiratory- and circulatory-associated conditions such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, AE, and heart failure. These complications were similar to those reported for COPD and IPF patients [43, 44]. Severe pulmonary dysfunction leads to respiratory complications such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, and AEs in both COPD and IPF patients [19, 45, 46]. In patients with COPD, endothelial dysfunction and remodeling of the pulmonary vascular bed are considered to be associated with hypoxia and systemic inflammation, which might contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease [43, 47]. Patients with IPF have an increased risk of vascular disease in comparison with the general population [48]. In CPFE, the unravelling mechanisms in common with COPD and IPF could lead to these complications.

We also found a mild association between smoking pack-years and hospitalization events. Smoke-induced oxidative damage induces regenerating precursor cells in both IPF and COPD, which might lead to abnormal tissue remodeling and functional impairment in these diseases [49]. A positive smoking history has been found to increase mortality in patients with IPF [50]. In patients with COPD, the cessation of smoking reduces the risk of exacerbation [51] and subsequent mortality, even in patients with severe disease [52]. Furthermore, continuous smoking affects the progression of disease in patients with CPFE more strongly than former smoking does [53]. Therefore, the cessation of smoking is considered to essential for patients with CPFE.

Physiological measurements of lung function have been conventionally performed to evaluate disease severity in patients with lung disease. However, computer-based HRCT image analysis has greatly improved, and has enabled us to assess the extent of lung disease and to quantify morphological changes [54, 55]. The recently introduced densitometric- and histogram-based analysis of CT images provides data on mean lung attenuation, skewness, and kurtosis. These parameters have been reported to show associations with parameters of pulmonary function and disease progression in various lung diseases [56]. In addition, some objective CT measurements have been found to be useful for the long-term monitoring of patients with emphysematous and fibrotic lung disease [25, 57, 58]. Quantitative CT assessments, as well as other biomarkers, might be useful for the assessment of disease severity and prediction of the clinical course of patients with CPFE [59].

This study has limitations. First, this was a single-center study with a small number of enrolled patients and the pulmonary function of the subjects was preserved compared to previous studies [1, 4, 6, 12]. The numbers of AEs and hospitalizations were low compared with those numbers in previous studies of patients with COPD, IPF, or CPFE [7, 19, 42]. Second, samples were not taken from patients for a histopathological evaluation. Third, the inner spaces of honeycombing and airspace enlargement associated with fibrosis might have been assessed as LAA. However, reports on the measurement of honeycombing with a background of fibrotic lesions are rare, and methodologies for distinguishing between honeycombing and LAA have not been elucidated [56]. Additionally, pulmonary vessels were partially included in the HAA values. However, the indices of fibrosis and emphysema that were obtained using the quantitative methods in our study reflected pulmonary function and were associated with hospitalization events.

Conclusion

In conclusion, objective quantitative CT measurements were significantly associated with the results of PFT and with the hospitalization of patients with CPFE. Quantitative CT measurements might serve as a useful method to determine the lung morphology, pathophysiology and clinical course of patients with CPFE.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Akira Nishiyama, Mrs. Chieko Handa, Mrs. Tamie Hirano, and Mrs. Mika Sakurai for their technical assistance and general support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files (S1 Appendix).

Funding Statement

NK recieved the grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (16K01407,19K12816), the Chiba Foundation for Health Promotion & Disease Prevention(No.1272). Koichiro T recieved the grants from the Respiratory Failure Research Group (H26-Intractable diseases-General-076) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cottin V, Nunes H, Brillet PY, Delaval P, Devouassoux G, Tillie-Leblond I, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. The European respiratory journal. 2005;26(4):586–93. Epub 2005/10/06. 10.1183/09031936.05.00021005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, et al. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(10):897–906. Epub 2011/03/11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mejia M, Carrillo G, Rojas-Serrano J, Estrada A, Suarez T, Alonso D, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: decreased survival associated with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2009;136(1):10–5. Epub 2009/02/20. 10.1378/chest.08-2306 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jankowich MD, Rounds SIS. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a review. Chest. 2012;141(1):222–31. Epub 2012/01/05. 10.1378/chest.11-1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2018;198(5):e44–e68. Epub 2018/09/01. 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cottin V, Le Pavec J, Prevot G, Mal H, Humbert M, Simonneau G, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome. The European respiratory journal. 2010;35(1):105–11. Epub 2009/08/01. 10.1183/09031936.00038709 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishaba T, Shimaoka Y, Fukuyama H, Yoshida K, Tanaka M, Yamashiro S, et al. A cohort study of mortality predictors and characteristics of patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. BMJ open. 2012;2(3). Epub 2012/05/17. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papiris SA, Triantafillidou C, Manali ED, Kolilekas L, Baou K, Kagouridis K, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2013;7(1):19–31; quiz 2. Epub 2013/02/01. 10.1586/ers.12.80 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papaioannou AI, Kostikas K, Manali ED, Papadaki G, Roussou A, Kolilekas L, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: The many aspects of a cohabitation contract. Respiratory medicine. 2016;117:14–26. Epub 2016/08/06. 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitaguchi Y, Fujimoto K, Hayashi R, Hanaoka M, Honda T, Kubo K. Annual changes in pulmonary function in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: over a 5-year follow-up. Respiratory medicine. 2013;107(12):1986–92. Epub 2013/07/16. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.015 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akagi T, Matsumoto T, Harada T, Tanaka M, Kuraki T, Fujita M, et al. Coexistent emphysema delays the decrease of vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory medicine. 2009;103(8):1209–15. Epub 2009/03/03. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.02.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ando K, Sekiya M, Tobino K, Takahashi K. Relationship between quantitative CT metrics and pulmonary function in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Lung. 2013;191(6):585–91. Epub 2013/10/03. 10.1007/s00408-013-9513-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi SH, Lee HY, Lee KS, Chung MP, Kwon OJ, Han J, et al. The value of CT for disease detection and prognosis determination in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE). PloS one. 2014;9(9):e107476 Epub 2014/09/10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuoka S, Yamashiro T, Matsushita S, Kotoku A, Fujikawa A, Yagihashi K, et al. Quantitative CT evaluation in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: correlation with pulmonary function. Academic radiology. 2015;22(5):626–31. Epub 2015/03/03. 10.1016/j.acra.2015.01.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin KE, Chung MJ, Jung MP, Choe BK, Lee KS. Quantitative computed tomographic indexes in diffuse interstitial lung disease: correlation with physiologic tests and computed tomography visual scores. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2011;35(2):266–71. Epub 2011/03/18. 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31820ccf18 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka S, Yamashiro T, Matsushita S, Fujikawa A, Kotoku A, Yagihashi K, et al. Morphological disease progression of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: comparison with emphysema alone and pulmonary fibrosis alone. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2015;39(2):153–9. Epub 2014/12/05. 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000184 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. The European respiratory journal. 2004;23(6):932–46. Epub 2004/06/29. 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.[Guideline of respiratory function tests—spirometry, flow-volume curve, diffusion capacity of the lung]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai zasshi = the journal of the Japanese Respiratory Society. 2004;Suppl:1–56. Epub 2004/11/30. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, Jenkins G, Kondoh Y, Lederer DJ, et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;194(3):265–75. Epub 2016/06/15. 10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitaguchi Y, Fujimoto K, Hanaoka M, Honda T, Hotta J, Hirayama J. Pulmonary function impairment in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema with and without airflow obstruction. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2014;9:805–11. Epub 2014/08/13. 10.2147/COPD.S65621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Cooper BG, Jensen R, Kendrick A, et al. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. The European respiratory journal. 2017;49(1). Epub 2017/01/04. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caminati A, Bianchi A, Cassandro R, Mirenda MR, Harari S. Walking distance on 6-MWT is a prognostic factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory medicine. 2009;103(1):117–23. Epub 2008/09/13. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.07.022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camiciottoli G, Bartolucci M, Maluccio NM, Moroni C, Mascalchi M, Giuntini C, et al. Spirometrically gated high-resolution CT findings in COPD: lung attenuation vs lung function and dyspnea severity. Chest. 2006;129(3):558–64. Epub 2006/03/16. 10.1378/chest.129.3.558 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch DA, Austin JH, Hogg JC, Grenier PA, Kauczor HU, Bankier AA, et al. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2015;277(1):192–205. Epub 2015/05/12. 10.1148/radiol.2015141579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BM, Austin JH, Newell JD Jr., D'Souza BM, Rozenshtein A, Hoffman EA, et al. Pulmonary emphysema subtypes on computed tomography: the MESA COPD study. The American Journal of Medicine. 2014;127(1):94.e7–23. Epub 2014/01/05. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouronte-Roibás C, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Raviña A, Ramos-Hernández C, Tilve-Gómez A, Rodríguez-Fernández P, et al. Influence of the type of emphysema in the relationship between COPD and lung cancer. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2018;13:3563–70. Epub 2018/11/23. 10.2147/COPD.S178109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park J, Hobbs BD, Crapo JD, Make BJ, Regan EA, Humphries S, et al. Subtyping COPD by using visual and quantitative CT imaging features. Chest. 2020;157(1):47–60. Epub 2019/07/10. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitaguchi Y, Fujimoto K, Hanaoka M, Kawakami S, Honda T, Kubo K. Clinical characteristics of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respirology (Carlton, Vic). 2010;15(2):265–71. Epub 2010/01/07. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01676.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciccarese F, Attinà D, Zompatori M. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE): what radiologist should know. La Radiologia Medica. 2016;121(7):564–72. Epub 2016/02/20. 10.1007/s11547-016-0627-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cottin V, Nunes H, Mouthon L, Gamondes D, Lazor R, Hachulla E, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome in connective tissue disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2011;63(1):295–304. Epub 2010/10/12. 10.1002/art.30077 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todd NW, Jeudy J, Lavania S, Franks TJ, Galvin JR, Deepak J, et al. Centrilobular emphysema combined with pulmonary fibrosis results in improved survival. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair. 2011;4(1):6 Epub 2011/02/18. 10.1186/1755-1536-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champtiaux N, Cottin V, Chassagnon G, Chaigne B, Valeyre D, Nunes H, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in systemic sclerosis: A syndrome associated with heavy morbidity and mortality. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2019;49(1):98–104. Epub 2018/11/10. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martinez-Garcia MA, Roman Sanchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–31. Epub 2005/08/02. 10.1136/thx.2005.040527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durheim MT, Collard HR, Roberts RS, Brown KK, Flaherty KR, King TE Jr., et al. Association of hospital admission and forced vital capacity endpoints with survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of a pooled cohort from three clinical trials. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2015;3(5):388–96. Epub 2015/04/22. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00093-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.du Bois RM, Weycker D, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Kartashov A, et al. Ascertainment of individual risk of mortality for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184(4):459–66. Epub 2011/05/28. 10.1164/rccm.201011-1790OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jo HE, Glaspole I, Moodley Y, Chapman S, Ellis S, Goh N, et al. Disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with mild physiological impairment: analysis from the Australian IPF registry. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2018;18(1):19 Epub 2018/01/27. 10.1186/s12890-018-0575-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farkhooy A, Janson C, Arnardottir RH, Malinovschi A, Emtner M, Hedenstrom H. Impaired carbon monoxide diffusing capacity is the strongest predictor of exercise intolerance in COPD. Copd. 2013;10(2):180–5. Epub 2013/04/04. 10.3109/15412555.2012.734873 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz AA, Pinto-Plata V, Hernandez C, Pena J, Ramos C, Diaz JC, et al. Emphysema and DLCO predict a clinically important difference for 6MWD decline in COPD. Respiratory medicine. 2015;109(7):882–9. Epub 2015/05/09. 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.04.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch DA, Godwin JD, Safrin S, Starko KM, Hormel P, Brown KK, et al. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172(4):488–93. Epub 2005/05/17. 10.1164/rccm.200412-1756OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujimoto K, Taniguchi H, Johkoh T, Kondoh Y, Ichikado K, Sumikawa H, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: high-resolution CT scores predict mortality. European radiology. 2012;22(1):83–92. Epub 2011/08/09. 10.1007/s00330-011-2211-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haruna A, Muro S, Nakano Y, Ohara T, Hoshino Y, Ogawa E, et al. CT scan findings of emphysema predict mortality in COPD. Chest. 2010;138(3):635–40. Epub 2010/04/13. 10.1378/chest.09-2836 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanabe N, Muro S, Hirai T, Oguma T, Terada K, Marumo S, et al. Impact of exacerbations on emphysema progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183(12):1653–9. Epub 2011/04/08. 10.1164/rccm.201009-1535OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012;186(2):155–61. Epub 2012/05/09. 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Natsuizaka M, Chiba H, Kuronuma K, Otsuka M, Kudo K, Mori M, et al. Epidemiologic survey of Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and investigation of ethnic differences. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;190(7):773–9. Epub 2014/08/28. 10.1164/rccm.201403-0566OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, Tzanakis N. Managing comorbidities in COPD. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2015;10:95–109. Epub 2015/01/23. 10.2147/COPD.S54473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behr J, Kreuter M, Hoeper MM, Wirtz H, Klotsche J, Koschel D, et al. Management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: the INSIGHTS-IPF registry. The European respiratory journal. 2015;46(1):186–96. Epub 2015/04/04. 10.1183/09031936.00217614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wrobel JP, Thompson BR, Williams TJ. Mechanisms of pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pathophysiologic review. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2012;31(6):557–64. Epub 2012/04/17. 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.029 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hubbard RB, Smith C, Le Jeune I, Gribbin J, Fogarty AW. The association between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and vascular disease: a population-based study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178(12):1257–61. Epub 2008/08/30. 10.1164/rccm.200805-725OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chilosi M, Poletti V, Rossi A. The pathogenesis of COPD and IPF: distinct horns of the same devil? Respiratory research. 2012;13:3 Epub 2012/01/13. 10.1186/1465-9921-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antoniou KM, Hansell DM, Rubens MB, Marten K, Desai SR, Siafakas NM, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: outcome in relation to smoking status. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;177(2):190–4. Epub 2007/10/27. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1759OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–52. Epub 2002/09/27. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2005;142(4):233–9. Epub 2005/02/16. 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chae KJ, Jin GY, Han YM, Kim YS, Chon SB, Lee YS, et al. Prevalence and progression of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in asymptomatic smokers: A case-control study. European radiology. 2015;25(8):2326–34. Epub 2015/02/15. 10.1007/s00330-015-3617-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohkubo H, Nakagawa H, Niimi A. Computer-based quantitative computed tomography image analysis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A mini review. Respiratory investigation. 2018;56(1):5–13. Epub 2018/01/13. 10.1016/j.resinv.2017.10.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ostridge K, Wilkinson TM. Present and future utility of computed tomography scanning in the assessment and management of COPD. The European respiratory journal. 2016;48(1):216–28. Epub 2016/05/28. 10.1183/13993003.00041-2016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mascalchi M, Camiciottoli G, Diciotti S. Lung densitometry: why, how and when. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017;9(9):3319–45. Epub 2017/12/10. 10.21037/jtd.2017.08.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loeh B, Brylski LT, von der Beck D, Seeger W, Krauss E, Bonniaud P, et al. Lung CT Densitometry in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis for the Prediction of Natural Course, Severity, and Mortality. Chest. 2019;155(5):972–81. Epub 2019/02/12. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.01.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takayanagi S, Kawata N, Tada Y, Ikari J, Matsuura Y, Matsuoka S, et al. Longitudinal changes in structural abnormalities using MDCT in COPD: do the CT measurements of airway wall thickness and small pulmonary vessels change in parallel with emphysematous progression? International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2017;12:551–60. Epub 2017/03/01. 10.2147/COPD.S121405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu X, Kim GH, Salisbury ML, Barber D, Bartholmai BJ, Brown KK, et al. Computed Tomographic Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. The Future of Quantitative Analysis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019;199(1):12–21. Epub 2018/07/10. 10.1164/rccm.201803-0444PP . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]