Abstract

The COVID-19 crisis has caused a number of significant challenges to the higher education sector. Universities worldwide have been forced to rapidly transition to online delivery, working at home, and disruption to research while concurrently facing the longer-term impacts in institution financial reform. Here, the impact of COVID-19 on academic staff in the medical radiation science (MRS) teaching team at Charles Sturt University are explored.

While COVID-19 imposes potentially the greatest challenge many of us will experience in our personal and professional lifetimes, it also affords the opportunity to objectively re-evaluate and, where appropriate, re-design learning and teaching in higher education. Technology has allowed rapid assimilation to online learning environments with additional benefits that allow flexible, mobile, agile, sustainable, culturally safe and equitable learning focussed educational environments in the post-COVID-19 “new normal”.

Keywords: Higher education, University teaching, COVID19, Medical radiation science

Résumé

La crise de la COVID-19 a entraîné un certain nombre de défis importants pour le secteur de l'enseignement supérieur. Les universités à travers le monde ont dû rapidement faire la transition vers la prestation distancielle des cours, le travail à la maison et les perturbations de la recherche, tout en faisant face aux conséquences à long terme de la réforme des finances institutionnelles. Dans cet article, les auteurs examinent l'impact de la COVID-19 sur le personnel de l’équipe d'enseignement en sciences de la radiation médicale (SRM) à l’Université Charles. Bien que la COVID-19 représente probablement le plus grand défi auquel plusieurs d'entre nous devront faire face dans notre vie personnelle et professionnelle, elle offre également une occasion de réévaluer de façon objective et, s'il y a lieu, de revoir la conception de l'apprentissage et de l'enseignement dans les études supérieures. La technologie a permis une assimilation rapide des environnements d'apprentissage en ligne, avec des avantages supplémentaires qui favorisent un environnement éducatif souple, mobile, agile, durable, culturellement sécuritaire et centré sur l'apprentissage dans la « nouvelle normalité » post- COVID-19.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has redefined the way we live.1 In the higher education sector, a number of significant challenges have been confronted during the COVID-19 crisis. Universities worldwide have been forced to rapidly transition to online delivery whilst concurrently facing the longer-term impacts of the loss of international student revenue.2 In the acute phase, reactive strategies were required to provide for the immediate safety of staff, students and for some, clinical practice sites. Once immersed in both Government and University restrictions and changes to procedure and practice, proactive approaches emerged to manage both the economic and educational impacts of COVID-19, and the implementation of the practices to help students study off campus and “catch up”, particularly with regard to practical activities and to prepare for the “new normal”. Here, the impact of COVID-19 on academic staff in the medical radiation science (MRS) teaching team and changes to service delivery are explored.

MRS at Charles Sturt University comprises a number of small postgraduate and research higher degree offerings supporting a marquee 4-year undergraduate degree with three specialisations (diagnostic radiography, nuclear medicine and molecular imaging, and radiation therapy). With 15 academic staff supporting 450 fulltime, on-campus undergraduate students across two campuses (Wagga Wagga and Port Macquarie), rapid transition to online, off-campus delivery and staff working-from-home arrangements in mid-March 2020 presented challenges. Nonetheless, both the University and the discipline were inherently agile. For MRS, the challenge was how to manage student clinical placements; those students already entrenched in a clinical department and those with impending clinical placements. Management of placement was confounded by decreasing workload at most clinical sites (as much as 90% at some sites), student safety concerns, travel restrictions, state border closures, and safety concerns from clinical sites (including infection control and lack of personal protective equipment). Confounding and compounding the stress associated with adapting to new working conditions, online teaching tools and more challenging learning environments was the uncertainty imposed by the dire economic position the COVID-19 crisis had left the higher education sector.2 , 3 Nationwide the immediate impacts of COVID-19 on University revenue were catastrophic and virtually all Australian universities confronted a large number of cost saving course closures and staff redundancies. While premature to conclude the MRS program will not be impacted by Charles Sturt University responses, the nature of the courses in engaging closely with community needs, particularly in the regions served by Charles Sturt University, the vibrant student numbers, the high demand for Charles Sturt University graduates, and the alignment of the MRS course with broader University philosophy provide some comfort for our MRS team.

Transitioning to online learning

MRS at Charles Sturt University transitioned from face to face teaching in the first half of session one 2020 to fully online commencing the second half of session one 2020 using a two-week mid-session break to assimilate academics and students. While a small number of subjects were already offered online, this was a significant adjustment for staff unfamiliar with online delivery and because Charles Sturt University migrated from the Adobe Connect platform (Adobe, San Jose, USA) to the Zoom platform (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, USA). While Zoom is fairly intuitive, academics were afforded a large number of training programs over an intensive period managed at the same time as the transition to working from home. A number of newer members of the teaching team, in particular, reported the raft of professional development sessions provided by Charles Sturt University allowed easy assimilation to the online teaching platform. Indeed, the Zoom lectures allowed academics to communicate more personally with students asking questions in class than traditional video conferencing approaches, especially for those students at the video conference receiving end. Under video conference facilities, questions asked from the student group are generally lost in a sea of faces. Zoom on the other hand, allows the students’ video feed to be centralised. Both staff and students have reported this feature to improve connectivity between academics and students.

Reflecting the diversity among the MRS teaching team, academic experiences during this transition varied substantially. For some, the transition to online learning was timely, welcomed and seamless. Indeed, COVID-19 offered a reset that allowed a more rapid transition to enhance student learning that may not have occurred without COVID-19. The agility and flexibility of the online delivery represents a more contemporary approach to learning and teaching that affords the benefits of real time face to face teaching but also the power to create equity in learning opportunities, overcome learning barriers for students less comfortable to engage in the physical class environment, and the potential to craft a more culturally safe learning environment. For those academics where the transition to online learning created opportunity, there was a general feeling that class attendance in the live sessions was higher than face to face classes, and that student engagement (eg. questions during class) was also higher and more broadly spread amongst students. Generally speaking, academics felt that delivery live via Zoom overcame a number of technical and quality issues often confronted with the video conferencing software used between the Wagga Wagga and Port Macquarie campuses. A number of academics were already using Adobe Connect for online teaching but the University licence was not sufficient to accommodate mass transition to online teaching; hence the need for the introduction of the Zoom platform. For classes already using Adobe Connect, the transition to Zoom was more problematic than those moving to online for the first time. Indeed, the failure of Adobe Connect due to over subscription for one class saw the entire cohort and academic transition to Zoom live during the class; academics and students learning to navigate the new platform together in real time.

Students adapted quickly to the online environment although those familiar with Adobe Connect had some teething issues with the transition to Zoom initially. First year students with only half a session face to face did not have strong learning patterns developed. Many students rely on recorded lectures and do not attend class, many living some distance from campus, so the opportunity for live online learning enriched their learning experiences. Students who are regular in face to face classes remain regular and highly engaged in the online environment. While broadly academics report higher attendance in live lectures using the online platform over the conventional face to face classes, some report lower engagement by students. This is in contrast to others feeling there is greater engagement. The difference lies in the forum of engagement. Students prefer to use the “chat” function to ask questions than to unmute and ask verbally; more engaged electronically but less engaged personally. Muting audio during lectures is expected but muting the video can be disconcerting for the academic delivering to a blank screen. Some academics are making video stream compulsory but given class attendance is not compulsory and muting the video stream can significantly improve internet connectivity and stream quality, most academics leave the decision to individual students. The main negative feedback received from students in relation to transition to the online environment is the impact on the social life of students. While education remains the primary purpose of professional education, the importance of the social interactions, personal growth, social networks and ultimately professional networks should not be undervalued.

Specifically relating to delivery of online classes, Zoom allowed rich class dynamics with whole class lectures and discussion supported by the capability to produce smaller breakout groups. Smaller groups, whether the smaller classes or the breakout groups in larger classes, tended to have higher engagement reflected in students being more likely to unmute video and audio streaming. These smaller breakout rooms also provided closer contact between academics and students that afforded the chance to perform informal welfare checks on the class in a declared “safe place”, something common in the face to face environment and with increased student engagement, enriched online. This is especially important given the challenges confronting our students with many emerging from drought and fire affected communities into the COVID-19 crisis. By way of example, a quick welfare check amongst one group of students revealed the following scenarios that allowed academic and students to rally and provide advice and support that might have otherwise been missed:

-

•

A student felt isolated and alone off-campus away from friends in coping with a close friend who had taken their own life. The student had not spoken to anyone about this and found the opportunity to engage openly with peers to lift considerable burden. Furthermore, the open discussion revealed the informal social support network that is readily available and became aware of formal support services offered through Charles Sturt University, Health department and the community.

-

•

A student had received no counselling or support after an unsuccessful attempt to resuscitate a customer at their part time workplace and expressed the disturbances to sleep patterns since the event, and anxiety associated with regularly serving the deceased customer's close relatives in the weeks since the event. This was another scenario where the student was directed to appropriate support but also heard the shared insights from others within the group who had confronted similar scenarios.

The flexibility of the online learning environment also allows more novel approaches to the class environment. Multiple lecturers delivering concurrently is difficult to manage in the face to face environment despite Charles Sturt University being familiar with concurrent lecture delivery between Wagga Wagga and Port Macquarie campuses. Indeed, this creates a sense of two distinct cohorts that can cultivate perceptions of inequity between the two. The online environment creates a single cohort, greater equity and improves delivery. A number of academic staff reported improved interactions and relationships with students on the remote campus using Zoom compared to the customary video conferencing technology. The Zoom platform allows flexibility for multiple academics to join discussions remotely, making revision classes more fruitful. It also affords the chance for richer engagement with industry using guest lectures from industry experts without the requirement for them to leave their site and attend one of the two campuses. This simple flexibility also means a broader reach for guest lecturers both nationally and internationally. Indeed, Zoom has allowed real time guest lectures to be organised with our first year cohort from the author of their textbook in the USA and a number of guest lectures have been organised from leading international experts our students would not otherwise have exposure to.

As a rural provider of higher education, many students at Charles Sturt University do not originate from the community that hosts their course. This is also true in MRS where students come from all over Australia to attend either our Wagga Wagga or Port Macquarie campuses. With this, for some, comes a significant financial burden that can become prohibitive of academic progress, professional growth and personal development. Online learning has allowed students to live away from campus which may allow cheaper living costs and for students to have part time employment. It is certainly an important consideration post COVID-19 when defining what will be the “new normal” in MRS student education. Nonetheless, a number of students reported less than reliable internet access that inhibited their ability to participate in live classrooms. Physical classroom space, especially for large cohorts, is expensive to create and under high demand. For cohorts requiring two large spaces to be concurrently available for timetabling (Wagga Wagga and Port Macquarie) with capacity for live video feed between the two, this often pushes scheduled classes after hours. Online learning can not only decrease the physical space investment of the University but can ensure delivery for staff and students during normal working hours; enormously important for a family friendly university and contributing to physical safety (eg. not navigating campus after hours). It also provides greater sustainability by minimising waste. For example, there are significant cost, energy and capital waste associated with a venue booking to accommodate a class of 150 when only 30 attend face to face regularly.

Perhaps the biggest challenge and source of stress for academic staff was the transition from centrally administered invigilated exams to online examination. These circumstances did, however, afford the opportunity to re-evaluate practice and objectively shape learning, teaching and assessment in a more authentic way; expediting organic developments that may have taken several years. There was a general lack of familiarity with the online test centre tool among staff due to dependence on paper based invigilated exams that required some intensive training workshops. For some staff, trying to coordinate the exam online in conjunction with implementing systems like proctoring software to minimise cheating or collusion was a significant challenge. For others, the opportunity to look more objectively at the role of assessment and create more authentic assessment using exam questions designed to draw out student understanding meant that there was no motivation for students to search notes or online for answers, or indeed to collude. In some cases, students were provided in the exam with the information that may be sourced online or in notes to make it very clear that the answer needs to delve into the students’ understanding of those concepts to synthesise new information or problem solve. This was well received by students and provided a richer and more authentic learning environment without the stress and burden of proctoring.

Transitioning to a work from home environment

For staff, Charles Sturt University transitioned to a “work from home if you can” policy at the end of the first half of session one 2020 (mid-March when students started their mid-session break and transitioned to online learning). Some MRS staff prefer to work on campus and keep home as a work free, or minimal, zone. Other staff enjoy the flexibility of working on campus and off campus. For example, a staff member may spend most of their time on campus for teaching and administration but prefer to work at home when focussing on research or subject development to reduce distractions. Still other staff have a more complex work relationship involving office work, working from home, clinical responsibilities and longer travel distances to campus (from home). Like the transition to online learning, the transition to working from home produced a spectrum of experiences among academic staff in MRS. The University was very supportive of the transition, especially with relocating University office equipment to establish a comfortable home office. A common theme linked to the broader Government lockdown during COVID-19 was the idea that we never leave the office. Creating some semblance of a schedule with regular breaks is essential for maintaining physical and mental health and wellbeing. Staff reported being more adaptive and efficient in using irregular pockets of time and more intentional communication with colleagues, particularly with respect to support.

For some, working from home increased productivity and decreased fatigue. This tended to be associated with staff with external commitments from Charles Sturt University (eg. clinical roles) or where they reside some distance from campus. In either case, reduced travel time produced by working at home increased productivity, decreased fatigue and was generally reported to improve both the physical and mental health and wellbeing of those academics. Counter to this scenario, other staff report spending more actual time working but less productivity as an outcome, greater fatigue and decreased physical and mental health and wellbeing. A number of staff experienced substantially increased hours because their work was readily available at home and used to fill gaps throughout the day well beyond normal working hours. Some staff reported feeling isolated from colleagues (socially and professionally) which raised issues about mental health and wellbeing. Still others opted to continue to work from the campus office for a variety of reasons:

-

•

Unreliable internet services at home,

-

•

Few distractions in the office,

-

•

Better technology set up in the office,

-

•

To accommodate the needs of family members (eg. young children, shift workers).

Critical for many is the lack of a physical support network of colleagues and the loss of incidental interactions with colleagues and students. That physical support network was particularly important to newer staff navigating the nuances of the higher education sector and their own professional development. Ready access to colleagues within the physical office space creates informal discussion and quick solutions or guidance that is not afforded in the work from home environment. Several academics observed that responsiveness to electronic communication is slow or absent. This may reflect difficulties managing a significant increase in electronic communication but also individual preferences with respect to communication style; some simply do not like communicating electronically. Furthermore, electronic communication has issues associated with context that can result in misunderstanding or miscommunication (eg. assuming tone or mood and “reading between the lines”). This can be damaging to relationships and the discipline when an email of importance to the author is deprioritised (no response) by leadership or is the subject of selective non-response by colleagues (that is, overlooked by colleagues while communication from another colleague is responded to). Of course, there may be no substance to these assumptions but in isolation from colleagues, these situations can quickly escalate. As a result, careful attention needs to be paid by all academics, but particularly those in leadership, to electronic communication in a work from home environment. More regular but informal Zoom meetings would be an excellent tool, but the complexity of the current circumstances have been prohibitive of that strategy's success. The potential for staff working from home, like students off campus, to feel isolated is important. Clearly the sense of isolation undermines the team-based approach and collegiality within the discipline fostered by conventional on campus interactions. Less obvious is the potential for staff to feel overwhelmed with the growing workload, stress associated with changes to the teaching landscape, impact of COVID-19 on the University and national community and economy, stress associated with potential redundancies for self and family, and general empathy for the dire circumstances our global community finds itself in. In some cases, academics in our team have family and friends impacted severely from COVID-19 abroad with isolation in the workplace compounded by the disempowerment of being helpless and distant to loved ones in need. As previously mentioned, the mental health and wellbeing, and the resilience of academics have been significantly challenged and in many cases masked by the agility and seamless assimilation in the face of COVID-19 imposed changes.

Working from home has decreased communication within the discipline and undermined collegiality and collaboration for some groups. More established collaborations within the group have more readily transitioned to online meetings. On our Port Macquarie campus, academic staff tend to have a regular coffee break together with informal discussion and inclusive of other colleagues outside the discipline. This very productive and collegial environment is facilitated by a compact campus with open plan, inter-disciplinary office space and, while hard to replicate online, has been substituted for daily Zoom based coffee breaks. Nonetheless, the less predictable nature with increased distractions associated with working from home decreases the regularity of attendance for some staff and, without the easy access to professional networks on campus, has evolved to less a social catch up and more a problem solving meeting. On our Wagga Wagga campus, staff gatherings are less regular and inclusive reflecting the sparseness of the campus and a more siloed environment created by discrete, discipline buildings and individual academic office spaces. Interestingly, attempts to create a Zoom based MRS morning tea failed miserably. Some newer staff found working from home a greater challenge when it came to navigating Charles Sturt University policy or procedure without ready access to more experienced staff to quickly point the way. In part, the flexibility and agility of Zoom created an influx of requests for Zoom meetings exceeding demand for face to face meetings pre-COVID-19. For some, the sheer volume of Zoom requests has been overwhelming and this may have created some disengagement of staff.

A significant challenge for staff transitioning to a work at home environment was sharing that experience with others in the household. Working at home is easier when only one member of the household is working at home. Some staff had the challenge of working at home compounded by other family members also working from home, and children doing home school. This was not only a drain on shared spaces but also on internet connection speed. The distractions associated with noise, in particular, presented a few problems with lectures or meetings being disrupted by others in the household. The sight of a colleague's spouse commando rolling across furniture to try to avoid (unsuccessfully) being captured in a video feed is an example of the challenges. Nonetheless, it is refreshing and collegial to have something more personal about online connections that empowers the collegiality of the team. This includes seeing colleagues in a more natural habitat, and fleeting glimpses of their families or pets (Fig. 1 ). The reverse was also identified as a benefit with staff reporting their families gained a deeper insight into their roles and responsibilities as an academic, and an appreciation of some of the challenges the position confronts; bursting the bubble perhaps of the academic life being an easy job. A number of staff reported significant changes to working hours to create free space or distraction free periods; early hours of the morning and late at night typically. Clearly these habits readily lead to excessive work hours and potential issues with fatigue and potential burnout. While there are many positives associated with the flexibility of working from home, professional development programs should be developed to help staff adjust their work function to ensure maintenance of a healthy work life balance.

Fig. 1.

Screen captures from a live Zoom meeting among the authors of this article with family, pets and backgrounds not only providing a glimpse into one another's lives but also making communication more personal.

Impact on academic activities

The timing of COVID-19 and the “lockdown” strategies of the Government and University created a number of challenges for practical delivery. A number of subjects have practical activities that enrich student learning. This may be structured practicals in physics or anatomy/physiology subjects, or clinical skill focussed practicals simulated in the Charles Sturt University MRS laboratories. In the case of the structured theory enhancing practicals, these are difficult to deliver in advance of the theory or, indeed, disconnected from the theory. For the MRS teaching team, practicals tend to be skill or capability based and have some flexibility about timing of delivery, but also confounded by the requirement to precede student placement at a clinical centre. Third year of nuclear medicine, for example, requires a series of pre-clinical preparedness practicals to be undertaken in instrumentation and radiopharmacy before students attend clinical placement in April. Ultimately the significant downturn in workflow in clinical departments meant that all students delayed their clinical placement until later in the year when the learning environment was richer. Nonetheless, before Australia's first case of COVID-19 we were able to adjust practicals to be COVID compliant and bring them forward before “lockdown” measures would have been prohibitive.

For diagnostic radiography students, a number of critical simulation practicals had been delayed and at the time of writing, relaxation of “lockdown” requirements has seen an opportunity for intensive residential style on-campus practical sessions explored in smaller groups. The opportunity to enrich student learning with utilisation of simulation software (eg. Shaderware virtual radiography simulation) is an opportunity emerging out of the forced “lockdown”. Radiation therapy had to negotiate and coordinate remote access to simulation software for students. There are also projects in the pipeline before COVID-19 emerged to develop internal virtual reality simulation tools for nuclear medicine; production of which has been halted by COVID-19. COVID-19 has also increased the value of the extensive library of video practicals where skills and capabilities are demonstrated to students, building their confidence ahead of more intensive hands on practicals.

Whether practicals have been managed ahead of “lockdown” or postponed, a number of strategies needed to be employed to ensure COVID-19 safe practicals. While these COVID-19 variations mirror initiatives put in place in the clinical environment,4 , 5 they also have similar implications for resource utilisation, staffing and efficiency. Indeed, reduced student numbers per group, non-contact activities, use of gloves and masks, and sanitising between students all increase time requirements, resources utilisation and staff workload. Specific examples include, without being limited to:

-

•

Social distancing in laboratories reducing the number of students undertaking practicals concurrently.

-

•

Social distancing in laboratories changing supervision practices for staff.

-

•

No contact practicals requiring gloves to be worn to handle equipment and phantoms.

-

•

Sanitising equipment and phantoms between students.

-

•

Gloves and face masks to be worn when more than one student is in a practical space.

-

•

De-cluttering work spaces and prohibition of pens, notebooks or other vehicles for spread being used in practical spaces.

COVID-19 has been particularly disruptive to student learning and this creates a number of important considerations. Students should not be disadvantaged and both the University and the MRS team are supportive of accommodating students’ needs and providing flexibility in progress. As discussed above, this has included changes to delivery of practical classes that has increased demand for time and resources. There is also a substantial increase in the administrative load for academics managing non-substantive grades and managing requests for extensions and special consideration. Postponement or early termination of clinical placement of students adds both layers of complexity and disproportionate demands on time for academic staff but also puts some students out of sequence for theoretical classes. This drives increased demand on teaching staff to deliver content flexibly for a split cohort of students learning in sequence and those students out of sequence due to clinical demands. Online learning has seen an increase in email and online traffic from students which, combined with increased electronic communication amongst staff and volume of professional development workshops (e.g., Zoom tutorials, online teaching workshops, online examination workshops), has challenged the mental health and wellbeing of staff.

In many cases, the most confronting challenge for students and staff was dealing with the unknown. Advice, policies, the workplace, and clinical industry all operated in a fluid environment, reactive to the immediate situation. Cancellations of student clinical placements, for example, whether initiated by the clinical site, the student or the University, were done with no forward plan, reactive and without uniformity. Inequity among students with respect to clinical displacement produced the flow on effects described above but also created significant stress associated with both the inconvenience but more importantly the unknown. Fortunately, after the early phase of the pandemic and associated restrictions, a clear window allowed forward thinking policy development that has supported students; leaving students comfortable with their progress and management plans.

The strain on clinical placement opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic was a global issue. In response to this, Dr Andrew Kilgour and A/Prof Geoff Currie at Charles Sturt University along with colleagues from Europe, Canada and Australia devised an international online conference via numerous Zoom and Teams meetings (Fig. 2 ). The “Simulation-Based Education in Radiography/MRS: A Response to COVID-19” conference was a free event that facilitated sharing of experiences of using simulation for clinical training via the Teams platform (Microsoft, Redmond, USA). With 40 speakers from the UK, Canada, USA, Australia, New Zealand, South America and Africa, joint plenaries, breakout sessions for radiation therapy, diagnostic radiography and nuclear medicine specialities, and over 900 delegates, a global perspective provided innovative solutions to students’ development using simulation. This included several presentations from Charles Sturt University on adaptation of simulation activities in the on-campus nuclear medicine laboratory and radiopharmacy for COVID-19 compliance.

Fig. 2.

The organising committee representing Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom meeting via Teams.

Impact on research

COVID-19 saw cessation of research involving human interaction. This had a direct impact on a number of academic research activities. Some data collection has halted but will recommence post COVID-19. The challenge for those academics is accommodating any bias in data associated with pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 cohorts. Face to face qualitative interviews in a significant project were halted and a variation on ethics approval needed to be sought to convert to online interviews; adding additional work and delays, and potentially decreasing participation due to connectivity barriers. A number of research projects simply terminated early using COVID-19 as a logical end point. In these cases, the impact will depend on the statistical power associated with the data actually collected. Perhaps the most important impact relates to time critical research. For example, undergraduate students enrolled in an integrated honours course have a window from January 2020 to October 2020 to collect, analyse and synthesise their results into a dissertation. The timing of COVID-19 significantly jeopardised a number of these projects that forced an urgent re-appraisal of projects and in some cases a change of direction to allow a non-human contact-based project. Nonetheless, applications for approval by compliance committees of these new projects come with their own delays for project progression. While Charles Sturt University would accommodate delays associated with this kind of misadventure, it remains sub-optimal for final year students to delay examination and graduation. Fortunately, the research cycle afforded opportunity during the COVID-19 “research shutdown” to progress development of project proposals and for analysis or writing up of completed data collections. For novice researchers, momentum is often a challenge and efforts over many months to get traction have been neutralised by COVID-19 and the realisation that these efforts will have to recommence at essentially the original baseline is disheartening. For many, being overwhelmed with teaching and administrative responsibilities during COVID-19 was prohibitive of any form of research mindset; repositioning teaching deprioritised research.

Assimilation into the “new normal”

Despite the stress associated with COVID-19 and the rapid implementation of strategies to accommodate COVID-19 in higher education, a number of opportunities have emerged. In particular, COVID-19 afforded a reset of learning and teaching practices that forced reflection on best practice. Objective evaluation of fitness for purpose of teaching and assessment strategies, student support and academic responsibilities provides the impetus to change established practice; changes that may have taken years to occur organically. Post COVID-19 there is an opportunity to re-engineer the higher education landscape for greater sustainability, more agile and flexible learning, with enhanced outcomes from richer learning experiences crafted within a culturally safe and equitably accessible learning environment. The “new normal”, like so many other aspects of society, including the health professions our students are be trained for, will reflect a hybrid of the best aspects of the COVID-19 model and the best aspects of the pre-COVID-19 practice. It remains too early to forecast the enduring impacts of COVID-19 on higher education practices, yet it is clear that digital literacies, global citizenship and sustainability lie as foundations strongly aligned with the online learning platforms.

It seemed to be a universal preference to continue teaching via Zoom even if that meant classes returned to a face to face environment. This reflects the improvement in transmission and recording quality over standard video conferencing methods but also provided the additional flexibility of remote attendance and for students to have both audio only and full video recordings as revision tools. Some academics envision greater versatility in providing mobilised learning through Zoom, with the potential to have second and/or third year of the program delivered via an online mode. This provides quality learning for students while providing the flexibility to attend classes remotely or participate live in person using a smaller room with no need for video conferencing facilities. These are important options to explore in providing more sustainable content delivery. Furthermore, Zoom provided a number of tools that enhanced learning in the online platform that would be valuable to utilise even in a face to face environment:

-

•

More personal interaction with students at remote sites than via video conferencing facilities.

-

•

Greater flexibility to share resources, videos and images outside a PowerPoint presentations on-the-fly during lectures.

-

•

The availability to share a whiteboard during a lecture to drill down on a concept, particularly where a sketch might help without the need for document scanners in class.

-

•

Emoji use to get a quick response progressing through a lecture.

-

•

The opportunity to build polls into lectures to monitor student progress.

-

•

Capacity to allow students to annotate slides enriches learning and problem solving in class.

-

•

The chat function allows all students to be engaged and increases involvement of students who would not typically ask questions in class.

-

•

Zoom contributes to equity of access and opportunity, and a culturally safer learning environment for students; overcoming a number of socioeconomic or cultural issues confronted in a typical cohort at a rural university.

An interesting option for Zoom has been the ability to customise video backgrounds. While frustrating if the background image or the individual fades in or out, these backgrounds are easy to set up reliably with a fairly uniform backdrop (light coloured wall) or using a green screen. Staff and students adjust their backgrounds and this provides an insight into mood, personality but importantly personalises the communication environment. As shown in Fig. 3 , one of our teaching team has used the green screen to provide interactivity with the image in a similar fashion to the way television weather reporters describe the weather. While not versatile enough for an entire class, it does provide an interactive way to run tutorials or revision of complex topics.

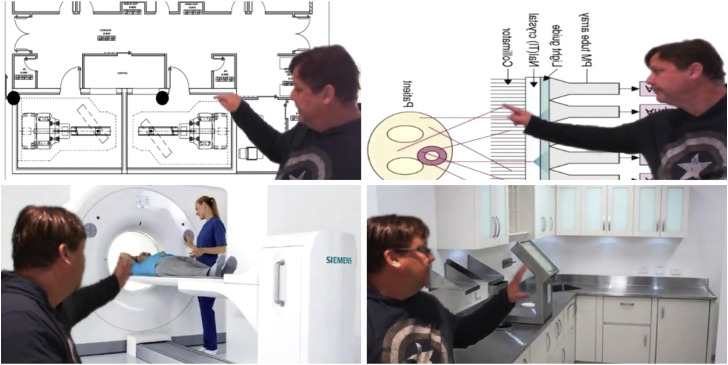

Fig. 3.

Screen captures from video recording of an academic using Zoom and a green screen to interact with the background image in the format of a television weather reporter to explain visual relationships. The top left is an overview of nuclear medicine department design, top right interactions with a gamma camera (note the green screen image was rotated and mirrored deliberately to move left to right through the system with the labels being redundant), bottom left patient positioning for PET/CT, and bottom right radiopharmacy design.

It is likely that most academics will return to face to face, invigilated exams in the post COVID-19 world; however, a number of academics now prefer the online exams. The online exams are not only a model of academic integrity but they are also more authentic, allow richer insight into achievement against subject learning outcomes, and allow more convenient and timely marking. The latter especially overcomes extended delays in exam marking when multiple examiners are required for different sections and exacerbated by shipping exams across campuses. Furthermore, the online exam option is paperless and more sustainable.

The “new normal” will see the emergence and greater utilisation of simulation software and the development of virtual reality simulation. With the threat of a second wave of COVID-19 and potential for similar novel viruses in the future, the “new normal” for Universities will see new standards for social distancing in the class and practical environments, increased precautions for surface sanitisation in student practical environments, and non-contact practicals.

Zoom also affords advantages for staff meetings over pre-COVID-19 video conferencing facilities and will continue to be used for scheduled and ad hoc meetings amongst staff and between staff and students. Nonetheless, Zoom poses a risk to collegiality and communication which means that the “new normal” will demand leadership within this space with particular attention to social isolation of colleagues, mental health and wellbeing, alternatives to electronic written communication, mentoring and induction of new staff.

Summary/Conclusion

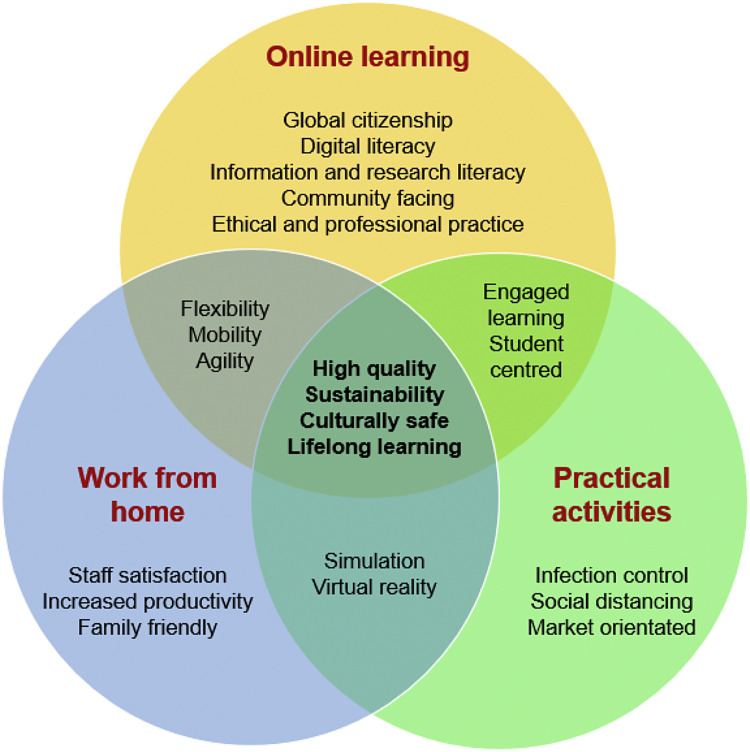

While COVID-19 imposes potentially the greatest challenge many of us will experience in our personal and professional lifetimes, it also affords the opportunity to objectively re-evaluate and, where appropriate, re-design learning and teaching in higher education. While technology allowed rapid assimilation to online learning environments, unexpected benefits far outweigh the difficulties. The post-COVID-19 “new normal” should integrate the quality and service provision benefits imposed during COVID-19 into a more flexible, mobile, agile, sustainable, culturally safe and equitable learning focussed educational environment (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the merits of the post-COVID19 “new normal” higher education strategies in MRS, and the interplay/connectedness between strategies and outcomes.

Footnotes

Funding: This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Currie G. COVID19 impact on nuclear medicine: an Australian perspective. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1623–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burki T.K. COVID-19: consequences for higher education. Lancet. 2020;21:758. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesar M. Towards a post-Covid-19 ‘new normality?’: physical and social distancing, the move to online and higher education. Pol Futures Educ Internet. 2020;18(5):p556–p559. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie G. Post-COVID19 “new normal” for nuclear medicine practice: an Australasian perspective (invited commentary) J Nucl Med Technol. 2020;48:234–240. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.120.250365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie G. A lens on the post-COVID19 “new normal” for imaging departments. J Med Imag Radiat Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2020.06.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]