Abstract

Common IRF5 genetic risk variants associated with multiple immune-mediated diseases are a major determinant of interindividual variability in pattern-recognition receptor (PRR)–induced cytokines in myeloid cells. However, how myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 regulates the multiple distinct checkpoints mediating T cell outcomes in vivo and IRF5-dependent mechanisms contributing to these distinct checkpoints are not well defined. Using an in vivo Ag-specific adoptive T cell transfer approach into Irf5−/− mice, we found that T cell–extrinsic IRF5 regulated T cell outcomes at multiple critical checkpoints, including chemokine-mediated T cell trafficking into lymph nodes and PDK1-dependent soluble Ag uptake, costimulatory molecule upregulation, and secretion of Th1 (IL-12)– and Th17 (IL-23, IL-1β, and IL-6)–conditioning cytokines by myeloid cells, which then cross-regulated Th2 and regulatory T cells. IRF5 was required for PRR-induced MAPK and NF-κB activation, which, in turn, regulated these key outcomes in myeloid cells. Importantly, mice with IRF5 deleted from myeloid cells demonstrated T cell outcomes similar to those observed in Irf5−/− mice. Complementation of IL-12 and IL-23 was able to restore T cell differentiation both in vitro and in vivo in the context of myeloid cell–deficient IRF5. Finally, human monocyte-derived dendritic cells from IRF5 disease-associated genetic risk carriers leading to increased IRF5 expression demonstrated increased Ag uptake and increased PRR-induced costimulatory molecule expression and chemokine and cytokine secretion compared with monocyte-derived dendritic cells from low-expressing IRF5 genetic variant carriers. These data establish that myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 regulates multiple distinct checkpoints in T cell activation and differentiation and that these are modulated by IRF5 disease risk variants.

Genetic variants in the IRF5 region that increase IRF5 mRNA (1) and protein (2) expression are associated with increased susceptibility to multiple immune-mediated diseases, including ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Sjogren disease, and systemic sclerosis (3, 4). This broad range of disease associations highlights a critical role for IRF5 in immunity and suggests that IRF5 may represent a nodal point for therapy of immune-mediated diseases. However, the mechanisms through which IRF5 contributes to disease susceptibility and how IRF5 genetic variants regulate these mechanisms are incompletely understood.

Studies in mice have supported a role for IRF5 in promoting Th1 and Th17 differentiation, which can in turn contribute to a broad range of immune-mediated diseases. In particular, Irf5−/− mice have generally displayed reduced Th1 and Th17 differentiation and increased Th2 differentiation in models of lupus, arthritis, asthma, and colitis (5–10), upon consumption of a high-fat diet (11), or in select infections (12). These T cell outcomes have been attributed to the altered responses in Irf5−/− myeloid cells that serve as APC (7, 9, 13, 14). Consistently, IRF5 is required for optimal responses to pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) on myeloid cells (2, 13, 15, 16). However, mechanisms for T cell– extrinsic IRF5 regulation of T cell activation and differentiation have not been clearly defined; such an understanding is essential to the ultimate design of therapeutic strategies targeting IRF5. In particular, there are multiple distinct checkpoints for T cell activation in vivo, and IRF5 may be regulating mechanisms contributing to one or more of these checkpoints. Clearly defining these requires an Ag-specific T cell system to enable the tracking of the responding T cells at distinct checkpoints in vivo. We therefore established systems with which to address T cell–extrinsic IRF5 and myeloid-intrinsic IRF5 contributions to T cell trafficking, activation, and differentiation in vivo and integrated these studies with mouse and human cells in vitro to define IRF5-dependent mechanisms for these outcomes. We further sought to define how the disease-associated variants in IRF5 modulate these outcomes.

In this study using Ag-specific DO11.10 CD4+ T cells, we found that T cell–extrinsic IRF5 promoted CD4+ T cell proliferation and regulated CD4+ T cell differentiation in vivo and, in particular, increased Th1 and Th17 differentiation and decreased Th2 and regulatory T (Treg) differentiation. T cell–extrinsic IRF5 regulated these outcomes through multiple distinct checkpoints, and we established mechanisms regulating these checkpoints. Myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 was sufficient to regulate T cell trafficking, proliferation, and differentiation in vivo, and complementation of IL-12 and IL-23 was able to restore T cell differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) from carriers of IRF5 disease-associated genetic risk variants leading to increased IRF5 expression demonstrated increased Ag uptake and increased PRR-induced costimulatory molecule upregulation and chemokine and cytokine secretion compared with MDDCs from low-expressing IRF5 genetic variant carriers.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Irf5−/− (BALB/c, 11 generations; generously provided by B. J. Barnes) mice were crossed to wild-type (WT) BALB/c mice to generate littermate controls. Irf5LoxP/LoxP mice (C57BL/6; stock no. 017311; The Jackson Laboratory) were crossed to LysM-Cre mice (stock no. 004781; The Jackson Laboratory). Cohoused littermate control mice were used in experiments. Thy1.1 DO11.10 BALB/c or Thy1.1 OTII C57BL/6J congenic mice were used in adoptive transfer experiments. Mice were maintained on autoclaved food and irradiated water in a specific pathogen-free facility with filtered air. Experiments were performed in agreement with our institutional care and use committee and according to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Abs and staining reagents

The following fluorophore-labeled Abs directed to mouse molecules used for flow cytometry were purchased from BioLegend: CD3, CD4, Thy1.1, DO11.10, TCR Vβ5.1/β5.2, IL-2, IL-17, T-bet, GATA3, CD80, ICAM1, CD45, CD19, CD11b, and CD64; from BD Biosciences: IL-4, MHC class II, TCR Vβ5.1/5.2, and RORγt; and from eBioscience: CD4, IFN-γ, IL-13, TGF-β, CD40, CD80, CD86, CD11c, and Foxp3. The following fluorophore- labeled Abs directed to human molecules were used from BD Biosciences: CD40, CD80, and ICAM1.

In vivo T cell activation

Splenic Thy1.1+ DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were isolated using CD4+ MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), stained with 1.5–2.5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes), and adoptively transferred by i.v. injection (0.5 × 106) into Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BALB/c mice. Twenty-four hours later, mice were immunized with s.c. 25 μg chicken OVA (MP Biomedicals) and 25 μg LPS (MilliporeSigma). Three days after immunization, peripheral lymph nodes (PLN) were harvested and stained with Abs to CD4, Thy1.1, and DO11.10. In other experiments, serum was harvested 2 wk after immunization for measurement of chicken OVA-specific isotype Abs. Ninety-six–well plates were coated with OVA (50 μg/ml) in PBS and plates ultimately incubated with IgG2a-, IgG2b-, or IgG1-conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (SouthernBiotech). For ex vivo detection of intracellular cytokines, cells were first treated with 2 μg/ml OVA peptide (323–339) (LifeTein) for 12 h and 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (MilliporeSigma) was added in the last 10 h. In some experiments, CFSE-labeled splenic Thy1.1+ DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (0.5 × 106) were first coated with 20 μg anti-mouse CCR7 neutralizing Ab (R&D Systems) for 30 min. In other experiments, 100 ng/mouse IL-12 (mouse)/Fc and 500 ng/mouse IL-23 (mouse)/Fc (AdipoGen Life Sciences) or Fc isotype controls (Bio X Cell) were injected i.v. into mice prior to immunization.

In vitro myeloid cell assays

Bone marrow cell suspensions were cultured in complete DMEM containing 20 ng/ml GM-CSF (PeproTech) to generate bone marrow–derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Cells were used at 6–8 d. In some cases, BMDCs were first treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A (Peptides International) for 24 h. In other cases, cells were cocultured with 10 μg/ml OVA-DQ (Invitrogen). In yet other cases, cells were cultured with 20 μM BAY 11–7082 (NF-κB inhibitor), 10 μM PD98059 (ERK inhibitor), 10 μM SB202190 (p38 inhibitor) (Calbiochem Research Biochemicals), or 10 μM GSK 2334470 (PDK1 inhibitor) (Tocris). The following were assessed by ELISA: IL-6, IL-12p40, and IL-23 (eBioscience); TNF (BioLegend); IL-1β, CCL2, CXCL2, CXCL9, and CXCL10 (PeproTech); and CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL9 (R&D Systems).

In vitro mouse T cell activation

Freshly isolated spleen-derived DO11.10 CD4+ T cells at 0.2 × 106 cells per well on 24-well plates were cultured with 0.2 × 105 BMDCs and 20 mg/ml chicken OVA for 72 h. In other cases, 20 μg/ml chicken OVA peptide (323–339) (LifeTein) was used. In some cases, 30 ng/ml IL-12 or 10 ng/ml IL-6 (PeproTech), 10 ng/ml IL-23, and 10 ng/ml IL-1β (eBioscience) were also added. The following were assessed by ELISA: anti– IFN-γ, biotin anti–IFN-γ, anti–TGF-β, biotin anti–TGF-β, anti–IL-10, anti–IL-2, and biotin anti–IL-2 (from BD Biosciences); anti–IL-17, biotin anti–IL-17, anti–IL-5, biotin anti–IL-5, anti–IL-13, and biotin anti– IL-13 (from eBioscience); and anti–IL-4, biotin anti–IL-4, and biotin anti–IL-10 (from BioLegend). Cell proliferation was assessed with MTT as per manufacturer instructions (MilliporeSigma).

T cell migration

In vitro migration assays were performed using Costar Transwell 5-μm pore size inserts. CD4+ splenic T cells (0.5 × 106) were placed in 100 μl serum-free medium in the upper well of the Transwell, and supernatants from lipid A–treated Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BMDCs were placed in the lower wells. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and cells migrating to the lower chamber were quantified by FACS analysis. In some cases, 20 ng/ml CCL19 and/or CCL21 (R&D Systems) was added to the lower well.

Protein analysis

For protein analysis of tissues, tissue was suspended in a Triton lysis buffer and homogenized, and ELISA was performed. Cells were lysed and protein detected by Western blot as per (2) and/or stained for analysis by flow cytometry with Abs to IRF5 (mouse [Abcam] and human E1N9G [Cell Signaling Technology]), p-ERK, ERK, p-IκBα, p-p38, p-PDK1, PDK1 (Cell Signaling Technology), IκBα, and p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). GAPDH Abs (mouse [MilliporeSigma] and rabbit [Cell Signaling Technology]) served as loading controls. For intracellular expression by flow cytometry, cells were fixed with Lyse/Fix Buffer (BD Biosciences) for 15 min, permeabilized for 1 h with Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences), washed, and then stained with the indicated Abs. Isotype controls were included for treated cells. In vivo studies were generally assessed on an LSR II and in vitro studies on an FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of BMDCs was performed according to a modified protocol (17) with anti-IRF5 (Abcam). Primers were designed to amplify genomic sequences at the cytokine gene promoter region (Supplemental Fig. 4D).

Donor recruitment and genotyping

Human cell studies were conducted as approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. Genotyping was performed by TaqMan (Life Technologies).

Primary myeloid cell culture

Human PBMCs were isolated from peripheral blood using Ficoll-Paque (Dharmacon). Monocytes were isolated and differentiated in 40 ng/ml GM-CSF (Shenandoah Technology Systems) and 40 ng/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems) for 7 d to generate MDDCs. ELISA was performed with IL-6 or IL-10 (BD Biosciences); IL-12p40, IL-1β, or IL-23 (eBioscience); IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, or TGF-β (BioLegend); CCL19 (R&D Systems); or CXCL10 (PeproTech).

Transfection of small interfering RNAs

One hundred nanomolar scrambled or siGENOME SMARTpool small interfering RNA (siRNA) against IRF5 (Dharmacon) (four pooled siRNAs for each gene) were transfected into macrophages using Amaxa Nucleofector Technology (Lonza).

Statistical analysis

Significance was assessed using two-tailed t test. A Bonferroni–Holm correction was applied for multiple comparisons where appropriate. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

T cell–extrinsic IRF5 increases T cell proliferation and enhances Th1 and Th17 but reduces Th2 and Treg differentiation in vivo

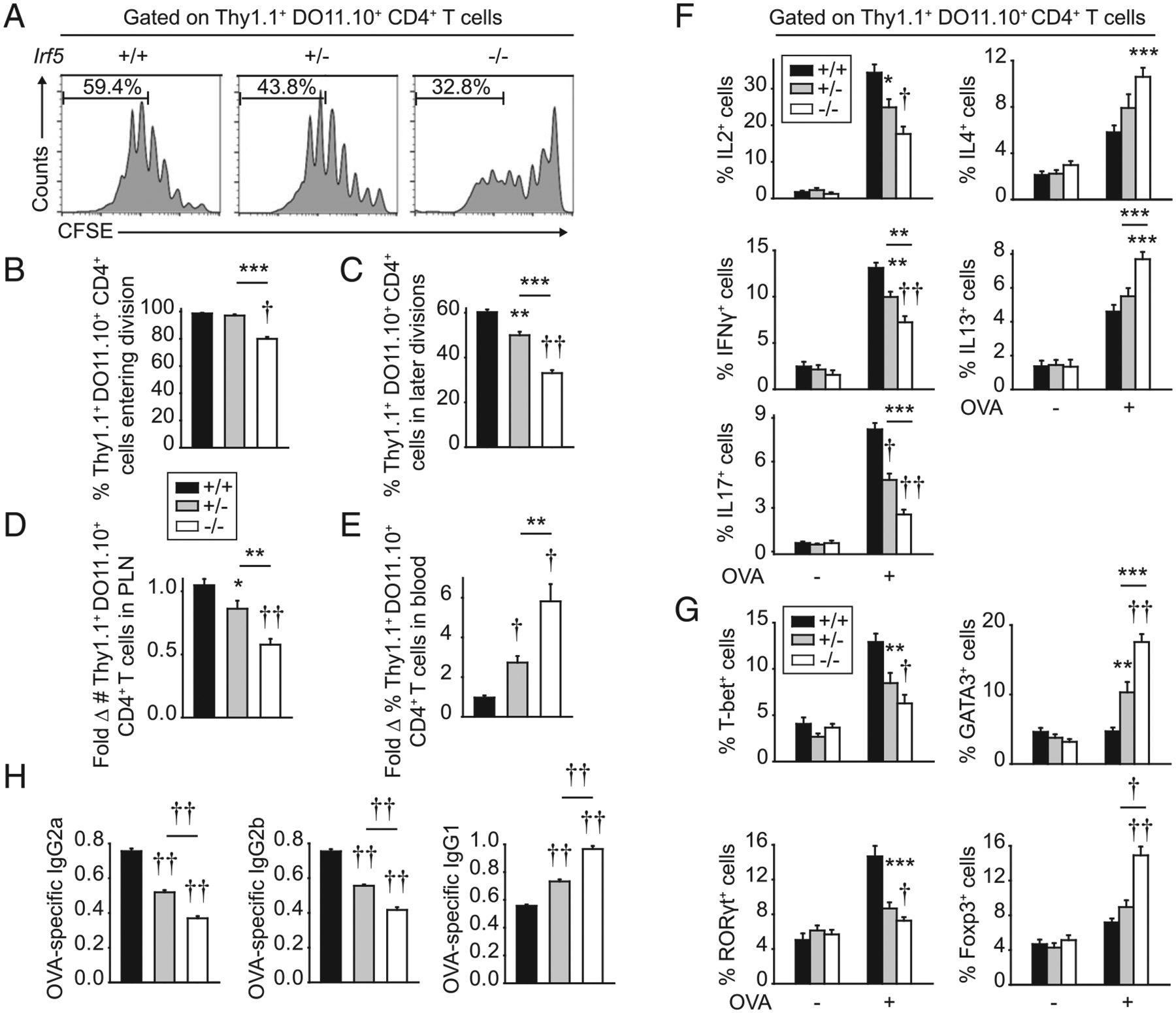

To assess the role of T cell–extrinsic IRF5 in the multiple distinct checkpoints required for T cell activation, we adoptively transferred Thy1.1+ WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells into cohoused littermate Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BALB/c mice so as to be able to assess physiological Ag-specific T cell activation and track the responding Ag-specific T cells. The next day, mice were immunized with s.c. OVA along with LPS as an adjuvant. Three days later, CD4+ T cells transferred into Irf5−/− mice demonstrated a decrease in T cells entering division as well as T cells progressing into later divisions in draining PLN compared with T cells transferred into Irf5+/+ mice (Fig. 1A–C, Supplemental Fig. 1A). Consistently, WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cell accumulation in Irf5−/− PLN was decreased after immunization (Fig. 1D); in contrast, WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cell accumulation in blood was increased in Irf5−/− relative to Irf5+/+ and Irf5+/− recipient mice (Fig. 1E). We next assessed T cell differentiation by examining cytokine production from the activated DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in the draining PLN. Consistent with the reduced CD4+ T cell proliferation, the fraction of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells producing IL-2 was reduced in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ recipient PLN (Fig. 1F, Supplemental Fig. 1B). The fraction of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ (Th1) and IL-17 (Th17) was also reduced in Irf5−/− draining recipient PLN (Fig. 1F, Supplemental Fig. 1B). In contrast, the fraction of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 (Th2) was increased (Fig. 1F). Consistent with the pattern of cytokine-producing DO11.10 CD4+ T cells, the fraction of T-bet+- and RORγt+-expressing DO11.10 CD4+ T cells was decreased, whereas that of GATA3+-expressing DO11.10 CD4+ T cells was increased in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ PLN recipients (Fig. 1G, Supplemental Fig. 1C). To our knowledge, T cell–extrinsic IRF5 regulation of Treg differentiation has not been clearly defined; we found that the frequency of Foxp3+-expressing DO11.10 CD4+ T cells was increased in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ PLN recipients (Fig. 1G, Supplemental Fig. 1C). We confirmed the Ag dependency for DO11.10 CD4+ T cell activation, as T cell entry and progression through divisions was minimal in the absence of immunization or with s.c. LPS compared with s.c. LPS/OVA, with only a low level of homeostatic proliferation observed (Supplemental Fig. 1D). Furthermore, the frequency of IFN-γ– and IL-17–producing cells was not increased with s.c. LPS compared with nonimmunized mice (Supplemental Fig. 1E). We also assessed if the altered differentiation of CD4+ T cells adoptively transferred into Irf5−/− mice persisted at later times after immunization. As expected, by days 5 and 7 after immunization, DO11.10 CD4+ T cells had entered and progressed through measurable cell divisions (Supplemental Fig. 1F). However, the decreased frequency of IFN-γ– and IL-17–producing and increased frequency of IL-4– and IL-13–producing DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ recipient PLN persisted (Supplemental Fig. 1G). Consistent with reduced Th1 and increased Th2 differentiation, Irf5−/− mice adoptively transferred with WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells demonstrated reduced OVA-specific IgG2a and IgG2b isotype switching and increased IgG1 isotype switching (Fig. 1H). Immunized Irf5−/− mice transferred with DO11.10 CD4+ T cells generally demonstrated an intermediate level of each of the measures assessed (Fig. 1). Therefore, T cell–extrinsic IRF5 promotes T cell proliferation and Th1 and Th17 differentiation while reducing Th2 and Treg differentiation.

FIGURE 1.

T cell–extrinsic IRF5 is required for optimal CD4+ T cell proliferation and differentiation in vivo. CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice. Twenty-four hours later, mice were immunized s.c. with 25 μg OVA/25 μg LPS. PLN were harvested 3 d after immunization. (A) Representative flow plots with percentage in later divisions shown (more than four divisions). Summary graphs of cells: (B) entering division (n = 3–4 per group; representative of four independent experiments), (C) in later divisions (n = 3–4 per group; representative of four independent experiments), and (D) number accumulated in PLN (n = 16–17 per group from four independent experiments). (E) Percentage of cells accumulated in blood (n = 12–13 per group from three independent experiments). (F and G) PLN cells were restimulated with 2 μg/ml OVA peptide (323–339) for 12 h. (F) Percentage of cytokine-producing Thy1.1+ DO11.10+ CD4+ T cells (n = 9–10 per group from two of three independent experiments). (G) Percentage of transcription factor–expressing Thy1.1+ DO11.10+ CD4+ T cells (n = 12–14 per group from three independent experiments). (H) Serum OVA-specific Abs at 2 wk (n = 12 per group from two independent experiments). Mean + SEM. Significance comparison is to Irf5+/+ mice or as indicated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

T cell–extrinsic IRF5 enhances T cell trafficking to lymph nodes

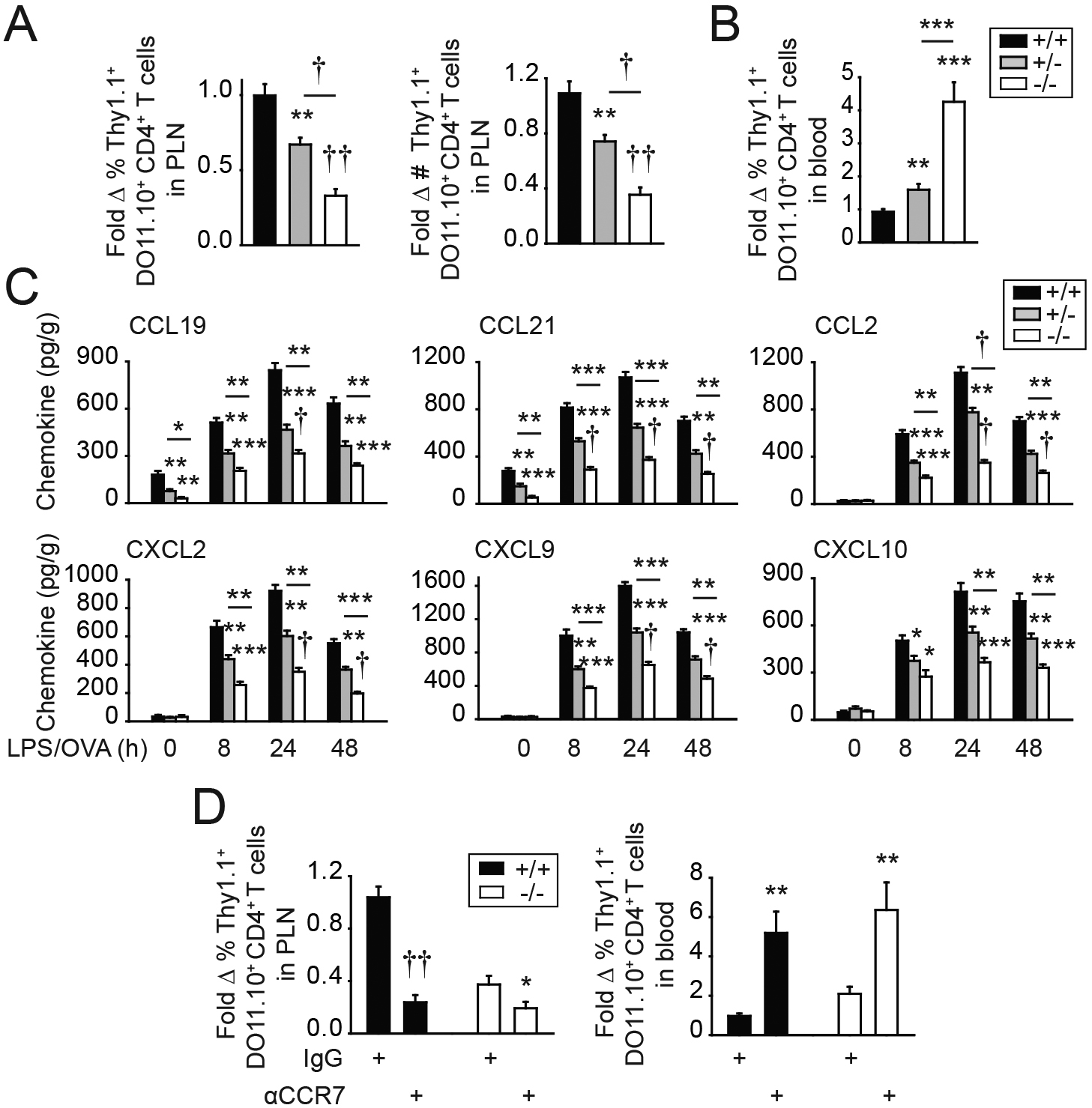

One of the initial checkpoints required for T cell activation is that of T cell trafficking to lymphoid structures. CD4+ T cell trafficking to PLN provides for a critical mass of Ag-responsive T cells, thereby allowing for optimal T cell proliferation upon immunization. To our knowledge, a role for T cell–extrinsic IRF5 in regulating T cell trafficking to lymph nodes has not been reported. Therefore, given the reduced CD4+ T cell proliferation and accumulation in Irf5−/− PLN after immunization (Fig. 1B–D), we assessed the trafficking of freshly isolated Thy1.1+ WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells to Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− PLN 16 h after adoptive transfer and prior to immunization. Trafficking of WT CD4+ T cells to Irf5−/− PLN was reduced compared with Irf5+/+ PLN, with reduced frequency and numbers of WT CD4+ T cells in Irf5−/− PLN (Fig. 2A). In contrast, higher frequencies of adoptively transferred WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were observed in blood of Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

T cell–extrinsic IRF5 is required for optimal CD4+ T cell trafficking to PLN. (A–C) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice. (A) Percentage and number of Thy1.1+ DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in PLN 16 h later (n = 9–10 per group from two independent experiments). (B) Percentage of Thy1.1+ DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in blood 16 h later (n = 9–10 per group from two independent experiments). (C) Twenty-four hours later, mice were immunized s.c. with 25 μg OVA/25 μg LPS and PLN were examined for chemokine expression at the indicated times after immunization (n = 4 per group per time point; additional independent experiment in nonimmunized and 24 h postimmunization mice). Significance is to Irf5+/+ mice or as indicated. (D) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ DO11.10 CD4+ cells were coated with isotype control or neutralizing anti-CCR7 Ab and then adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+ mice. Sixteen hours later, mice were assessed for percentage of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in PLN and blood (n = 8–9 per group from two independent experiments). Thy1.2+ Irf5−/− recipient mice are shown as a control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

Given the importance of chemokines in trafficking of naive CD4+ T cells, we assessed the homeostatic chemokines CCL19 and CCL21; these homeostatic chemokines interact with CCR7, and these interactions are critical for naive T cell migration into lymph nodes (18–21). CCL19 and CCL21 levels were reduced in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ PLN under baseline conditions (Fig. 2C). Levels of additional assessed nonhomeostatic T cell–attracting chemokines, including CCL2, CXCL2, CXCL9, and CXCL10, were not regulated by Irf5 genotype in PLN at baseline (Fig. 2C). However, upon immunization of mice adoptively transferred with WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells, levels of each of these chemokines in draining PLN were substantially increased relative to baseline levels but less effectively induced in PLN of adoptively transferred Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ mice at each of the time points examined (Fig. 2C). As the homeostatic chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 interact with CCR7, we used neutralizing CCR7 Abs to block these interactions on adoptively transferred WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells. Blocking CCR7 reduced the frequency of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells accumulating in PLN of nonimmunized mice (Fig. 2D) and, conversely, led to accumulation of the adoptively transferred DO11.10 CD4+ T cells in blood (Fig. 2D). These results confirm the important role of these chemokine interactions in mediating naive CD4+ T cell trafficking to PLN and show cell accumulation patterns similar to those in Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 2A, 2B). Consistent with the lower, but still detectable, levels of these chemokines in Irf5−/− PLN, CCR7 blockade in Irf5−/− mice led to additional reduction in the already decreased levels of CD4+ T cell trafficking (Fig. 2D). The levels of CD4+ T cell trafficking to both Irf5+/+ and Irf5−/− PLN were similarly low under these CCR7 blockade conditions (Fig. 2D). Taken together, IRF5 promotes production of homeostatic chemokines and of chemokines induced during an immune response, which, in turn, mediate the trafficking of T cells to lymph nodes.

IRF5 promotes the production of chemokines from myeloid cells, thereby enhancing CD4+ T cell migration

We next assessed cell subsets that might serve as a source of IRF5-dependent chemokines. IRF5 is expressed in myeloid cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages (2, 13, 15), and these cell subsets can secrete a range of chemokines. We confirmed reduced IRF5 expression in both BMDCs (Fig. 3A) and bone marrow– derived macrophages (BMMs) (Supplemental Fig. 1H) from Irf5−/− mice under unstimulated conditions and upon TLR4 stimulation (lipid A), which induces IRF5 expression. Irf5+/− cells expressed intermediate levels of IRF5 (Fig. 3A, Supplemental Fig. 1H). Upon lipid A treatment, Irf5−/− BMDCs secreted lower levels of chemokines (Fig. 3B). Similar results were observed in Irf5−/− BMMs (Supplemental Fig. 1I).

FIGURE 3.

IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for optimal PRR-induced chemokine secretion. (A–C) BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h. (A) IRF5 expression by Western blot. (B) Chemokine secretion (4 replicates per group; representative of two independent experiments). (C) CD4+ T cell migration to supernatants harvested from untreated or lipid A–treated BMDCs was assessed in vitro (six replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). Significance is to Irf5+/+ cells or as indicated. (D) CD4+ T cell migration to supernatants (supern) harvested from untreated or lipid A–treated BMDCs (Irf5+/+ and Irf5−/−) ± CCL19 and/or CCL21 (six replicates per group from two independent experiments). Medium ± CCL19 and/or CCL21 is included as a control. (E) Irf5+/+ BMDCs were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 4 h. ChIP was conducted with IRF5 (six replicates from two independent experiments). IgG and Irf5−/− BMDCs are included as negative controls (third independent experiment with Irf5+/+ BMDCs and IgG control). Mean + SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

We next assessed the functional implications of myeloid cell– derived chemokines. Consistent with the lipid A–induced chemokines from BMDCs (Fig. 3B), relative to supernatants from untreated BMDCs, supernatants from lipid A–treated BMDCs enhanced migration of WT CD4+ T cells in Transwell assays in vitro (Fig. 3C). However, T cells migrated to supernatants from lipid A–treated Irf5−/− BMDCs to a lesser degree (Fig. 3C). Importantly, complementing CCL19 or CCL21 in these Irf5−/− BMDC supernatants partially restored CD4+ T cell migration; combined CCL19 and CCL21 complementation more completely restored CD4+ T cell migration (Fig. 3D). As IRF5 is known to function as a transcription factor and, in particular, to bind to a range of cytokine promoters upon myeloid cell stimulation (13, 15, 22, 23), we assessed if IRF5 bound to the promoters of the lipid A–induced chemokines identified in these studies and found this was the case (Fig. 3E). Therefore, IRF5 in myeloid cells promotes PRR-induced chemokine secretion, which, in turn, mediates T cell migration.

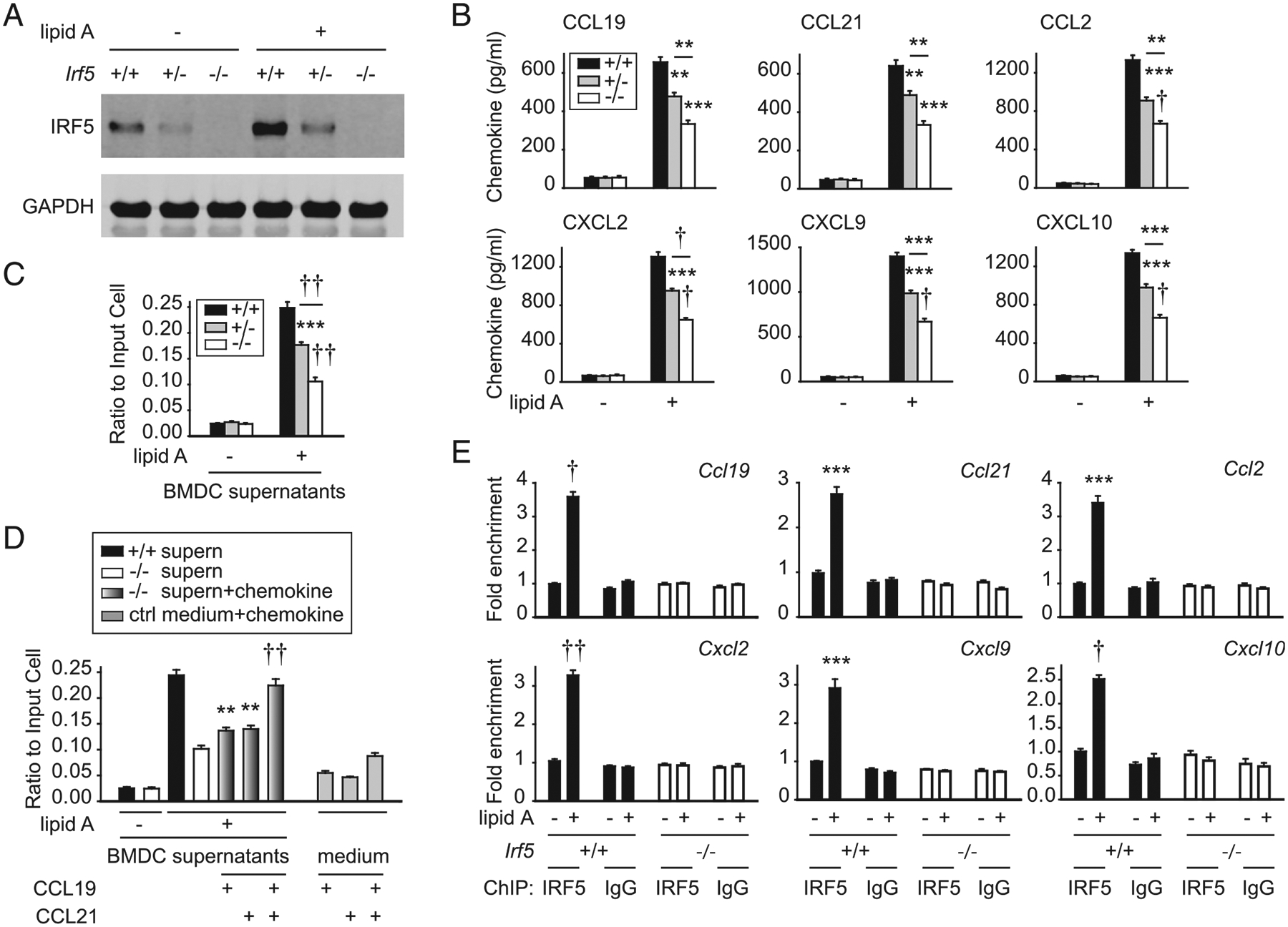

IRF5 in myeloid cells promotes Ag uptake

We next sought to define additional checkpoints (beyond T cell trafficking) through which T cell–extrinsic (and myeloid cell– intrinsic) IRF5 might contribute to T cell proliferation and differentiation. One of the initial steps in Ag presentation is the uptake of Ag by APCs. To our knowledge, prior studies have not reported a role for IRF5 in the essential process of soluble Ag uptake. We therefore first assessed the ability of APCs to take up Ag after s.c. immunization with OVA-DQ (DQ is a fluorophore that maintains stability at low pH). Four hours after immunization, compared with Irf5+/+ mice, Irf5−/− mice demonstrated a reduction in the frequency of cells among various APC subsets in PLN that had effectively taken up OVA-DQ, including MHC class II+ cells, B cells (CD19+ cells), and myeloid cells (CD11c+CD11b+CD19− cells and CD11b+CD11c−CD19− cells) (Fig. 4A). As CD11c+CD11b+ myeloid cells represent a mixed population, we further dissected these cells using CD64 expression (24, 25); CD64+ myeloid cells have been shown to be effective in Ag uptake (25). The frequency of CD11c+CD11b+CD64+CD19− cells taking up OVA-DQ was reduced in Irf5−/− PLN (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the frequency of CD11c+CD11b−CD19− cells in Irf5−/− mice taking up Ag was not reduced compared with Irf5+/+ mice (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for PDK1-dependent signaling pathways that regulate Ag uptake. (A) Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were immunized s.c. with 25 μg OVA-DQ, and 4 h later, the frequency of OVA-DQ+ cells within distinct APC subsets was assessed in draining PLN. Gating strategies, representative flow cytometry, and summary graphs are shown (n = 9 per group from two independent experiments for first two rows; n = 5 per group for CD64-fractionated subset in third row). (B) Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BMDCs were cocultured with 10 μg/ml OVA- DQ, and Ag uptake was assessed by flow cytometry (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) at the indicated time points (three replicates per group representative of two independent experiments; additional independent experiment at the 15 min time point). (C and D) Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BMDCs were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A and PDK1 phosphorylation was assessed at 15 min by (C) Western blot or (D) flow cytometry (three replicates per group; representative of two independent experiments). In representative flow cytometry for untreated cells MFI for only Irf5+/+ BMDCs is shown because of overlapping values. (E) WT BMDCs were treated with GSK 2334470 (PDK1 inhibitor [inhib]) or vehicle for 1 h prior to coculture with 10 μg/ml OVA-DQ. Ag uptake was assessed at the indicated times by flow cytometry shown as MFI (four replicates per group; representative of two independent experiments). Irf5−/− BMDCs are shown as a control; the low level of Ag uptake in Irf5−/− BMDCs decreased slightly consistent with the low level of PDK1 activation in these cells. Mean + SEM. Significance comparison is to Irf5+/+ mice or Irf5+/+ BMDCs or as indicated for (A), (B), and (D). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4.

To define IRF5 mechanisms mediating Ag uptake, we first ensured that Irf5−/− BMDCs demonstrated reduced Ag uptake in vitro. Ag uptake progressively increased in Irf5+/+ BMDCs over a 1-h period, but Irf5−/− BMDCs demonstrated consistently reduced OVA-DQ uptake over this time compared with Irf5+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 4B). The PI3K pathway can mediate soluble Ag uptake such that we assessed if IRF5 was required for PDK1 activation, as a measure of PI3K pathway activation, in response to lipid A. Lipid A–induced PDK1 activation was reduced, as assessed by both Western blot (Fig. 4C) and phosphoflow (Fig. 4D) in Irf5−/− compared with Irf5+/+ BDMCs. Irf5+/− BMDCs generally demonstrated an intermediate phenotype in these measures (Fig. 4A–D). A PDK1 inhibitor reduced OVA-DQ uptake by BMDCs (Fig. 4E), thereby establishing the role of this pathway in soluble Ag uptake by myeloid cells. Taken together, IRF5 promotes PRR-induced PDK1 activation in myeloid cells, which, in turn, regulates the uptake of soluble Ag.

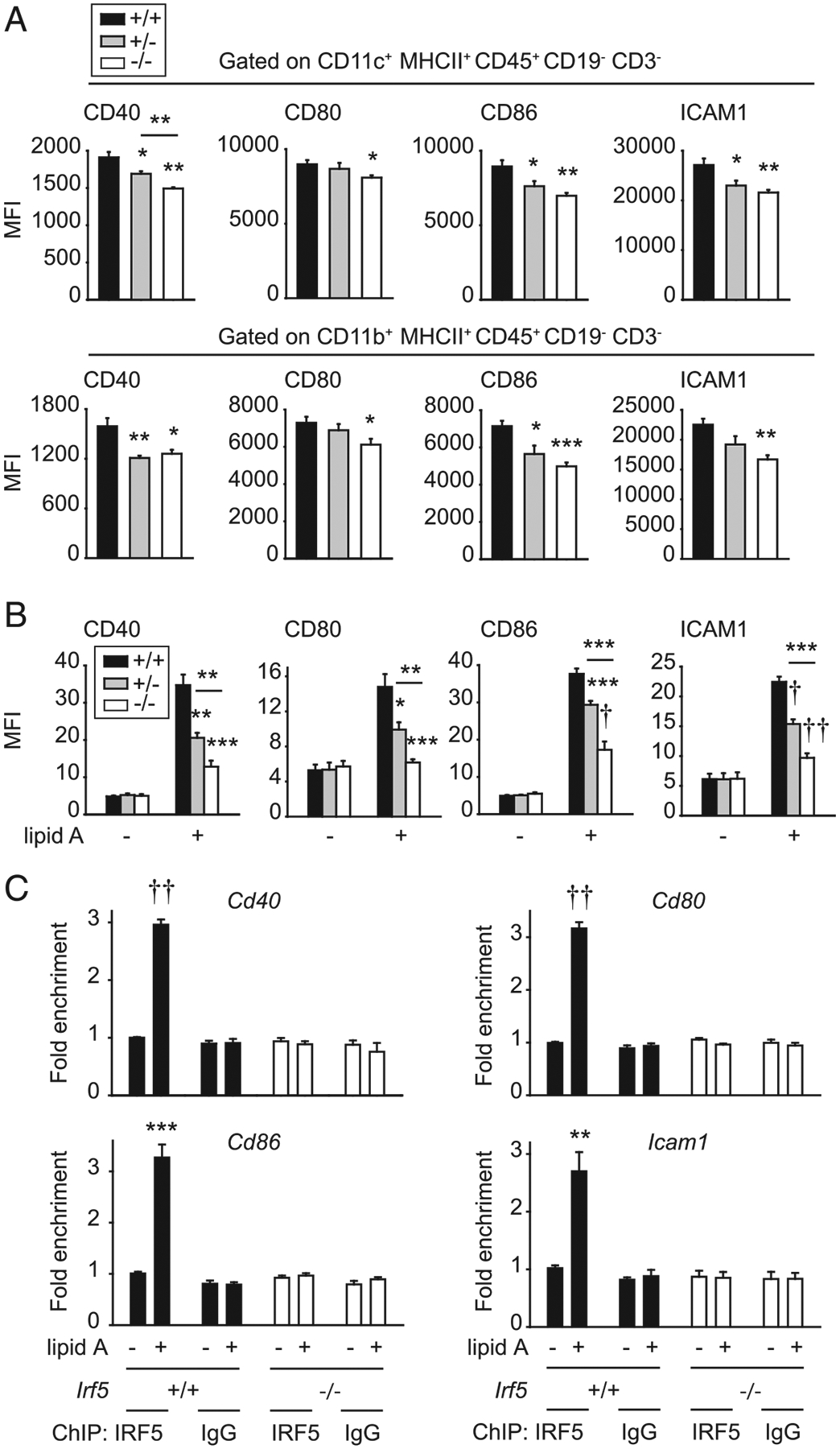

IRF5 in myeloid cells promotes PRR-induced costimulatory molecules

In addition to Ag uptake, costimulatory molecule upregulation by APCs is required for T cell activation. The frequency of various APC subsets (Supplemental Fig. 1J) and of costimulatory molecule expression on CD11c+ and CD11b+ APCs (Supplemental Fig. 1K) was not regulated by Irf5 genotype in PLN under homeostatic conditions. However, in PLN of Irf5−/− mice adoptively transferred with DO11.10 CD4+ T cells and immunized s.c. with LPS/OVA, upregulation of CD40, CD80, CD86, and ICAM1 was reduced on both CD11c+ and CD11b+ APCs compared with APCs in Irf5+/+ PLN (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the in vivo observations, direct stimulation of TLR4 on Irf5−/− BMDCs resulted in lower induction of costimulatory molecules as compared with Irf5+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 5B, Supplemental Fig. 2A). Irf5+/− APCs generally demonstrated intermediate levels of these measures (Fig. 5A, 5B). Consistent with the role of IRF5 as a transcription factor, IRF5 bound to the promoters of each of the IRF5-regulated costimulatory molecules upon lipid A treatment (Fig. 5C). Therefore, IRF5 in myeloid cells promotes TLR4-induced upregulation of costimulatory molecules in vivo and in vitro; in combination with IRF5 regulation of soluble Ag uptake, these findings highlight a role for IRF5 in Ag presentation.

FIGURE 5.

IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for costimulatory molecule upregulation. (A) Thy1.1+ WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice. Twenty-four hours later, mice were immunized s.c. with 25 μg OVA/25 μg LPS. Draining PLN were harvested 24 h after immunization, and CD11c+ or CD11b+ cells were assessed for expression of costimulatory molecules by flow cytometry. Summary graph with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (n = 4 per group). (B and C) BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A. (B) MFI of costimulatory molecules at 24 h (six to seven replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (C) ChIP was conducted with IRF5 at 4 h (six replicates per group from two independent experiments). IgG and Irf5−/− BMDCs are included as negative controls (third independent experiment with Irf5+/+ BMDCs and IgG control). Mean + SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

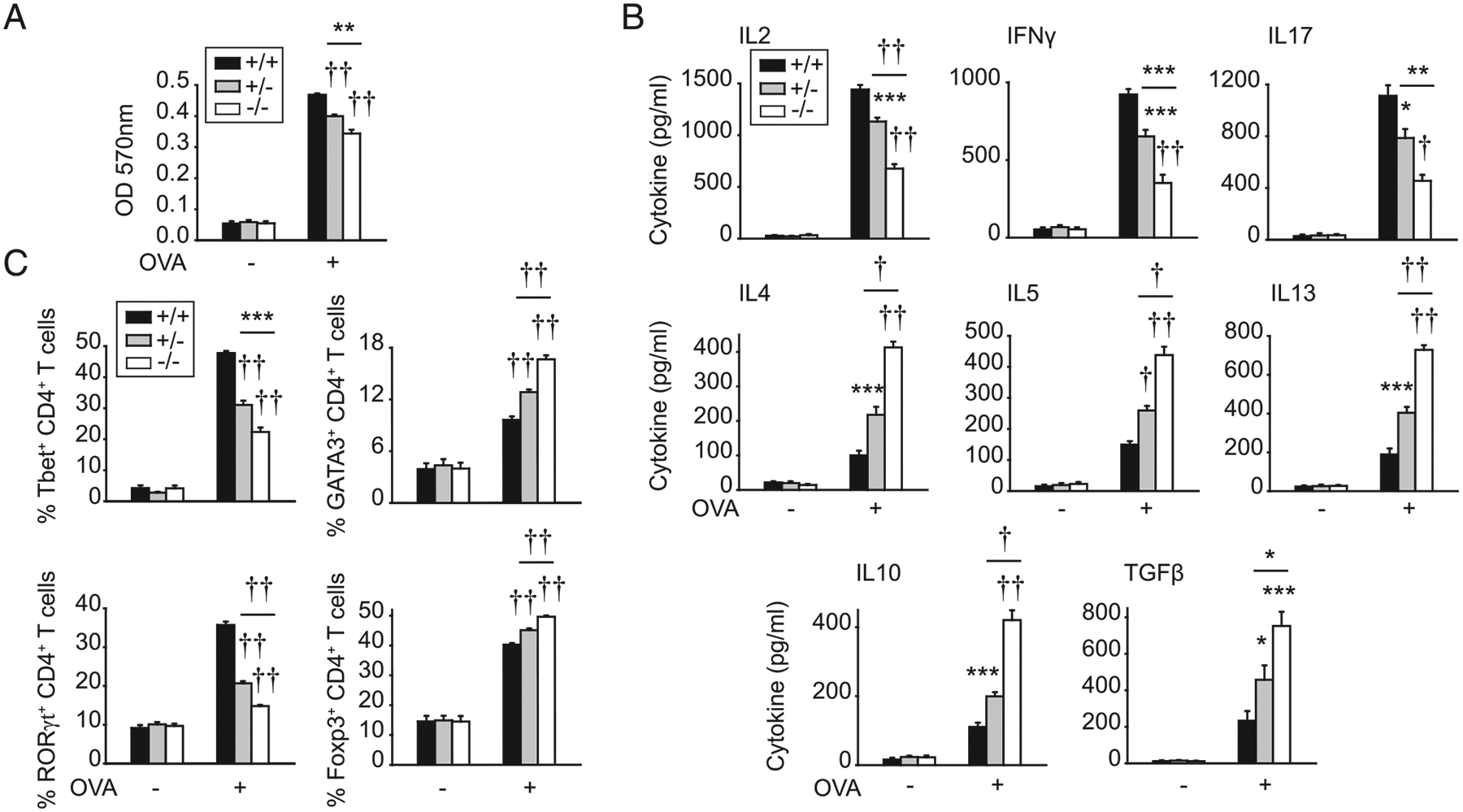

IRF5 on myeloid cells enhances T cell proliferation and regulates T cell differentiation in vitro

To define additional mechanisms through which IRF5 in APCs regulates T cell activation and differentiation, we conducted coculture studies of Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− BMDCs with WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells and OVA Ag. WT T cells cocultured with Irf5−/− BMDCs demonstrated reduced proliferation in vitro (Fig. 6A), similar to results in vivo (Fig. 1A–C). Consistently, the T cell growth factor IL-2 was reduced upon coculture of T cells with Irf5−/− BMDCs (Fig. 6B). Consistent with two prior studies (9, 13), T cells cocultured with Irf5−/− BMDCs also demonstrated reduced Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th17 (IL-17) differentiation and increased Th2 (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) differentiation (Fig. 6B). Consistent with our in vivo observations showing increased Foxp3-expressing CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1G), IL-10 and TGF-β secretion was increased upon coculture of T cells with Irf5−/− BMDCs and OVA (Fig. 6B). Transcription factors corresponding to the IRF5-mediated T cell differentiation outcomes were accordingly regulated, with a decreased fraction of T-bet–- and RORγt-expressing CD4+ T cells and an increased fraction of GATA3- and Foxp3-expressing T cells (Fig. 6C, Supplemental Fig. 2B). Note that T cells can coexpress transcription factors such that expression is not mutually exclusive (26–29). Coculture with Irf5+/− BMDCs led to intermediate outcomes (Fig. 6A–C).

FIGURE 6.

IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for optimal CD4+ T cell proliferation and differentiation upon coculture with Ag. BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h and then cocultured with OVA and DO11.10 CD4+ T cells for 72 h. (A) CD4+ T cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay (OD) (seven replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (B) Cytokines (seven replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (C) Transcription factors in CD4+ T cells assessed by intracellular flow cytometry (11 replicates per group from three independent experiments). Mean + SEM. Significance comparison is to Irf5+/+ BMDCs or as indicated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

To assess if the myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 regulation of T cell outcomes was observed independent of Ag processing, we conducted studies with OVA peptide. T cells cocultured with Irf5−/− BMDCs and OVA peptide demonstrated reduced proliferation (Fig. 7A) and cytokine secretion patterns (Fig. 7B) similar to that observed with whole OVA Ag. As we had observed that IRF5 regulates costimulatory molecule upregulation on myeloid cells in vivo upon immunization with OVA Ag (Fig. 5A), we asked if costimulatory molecules could also be regulated by IRF5 during coculture with OVA peptide in vitro. Irf5−/− BMDCs cocultured with CD4+ T cells and OVA peptide demonstrated reduced induction of costimulatory molecules compared with Irf5+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 7C). Therefore, myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 enhances T cell proliferation and increases Th1 and Th17 differentiation while decreasing Th2 and Treg differentiation.

FIGURE 7.

IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for optimal CD4+ T cell proliferation and differentiation upon coculture with peptide. BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h, and then cocultured with OVA peptide (323–339) and DO11.10 CD4+ T cells for 72 h. (A) CD4+ T cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay (OD) (eight replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (B) Cytokines (eight replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (C) Costimulatory molecules were assessed on cocultured BMDCs (four replicates per group; representative of two independent experiments). Mean + SEM. Significance comparison is to Irf5+/+ BMDCs or as indicated. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

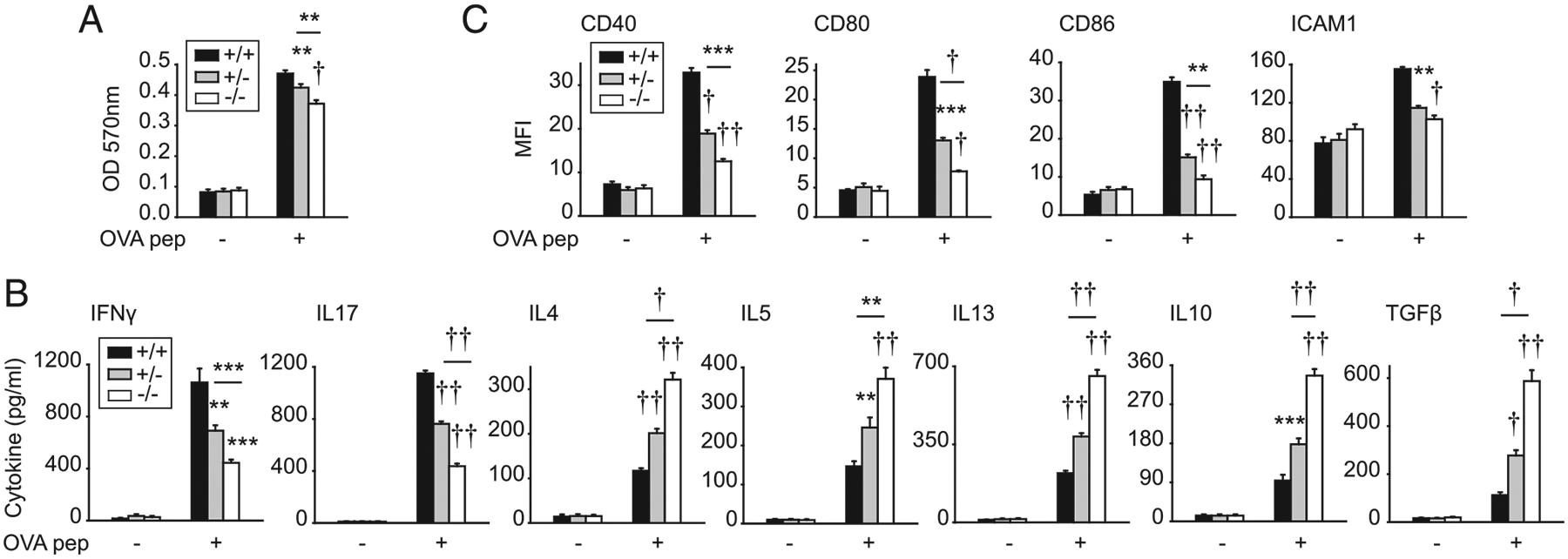

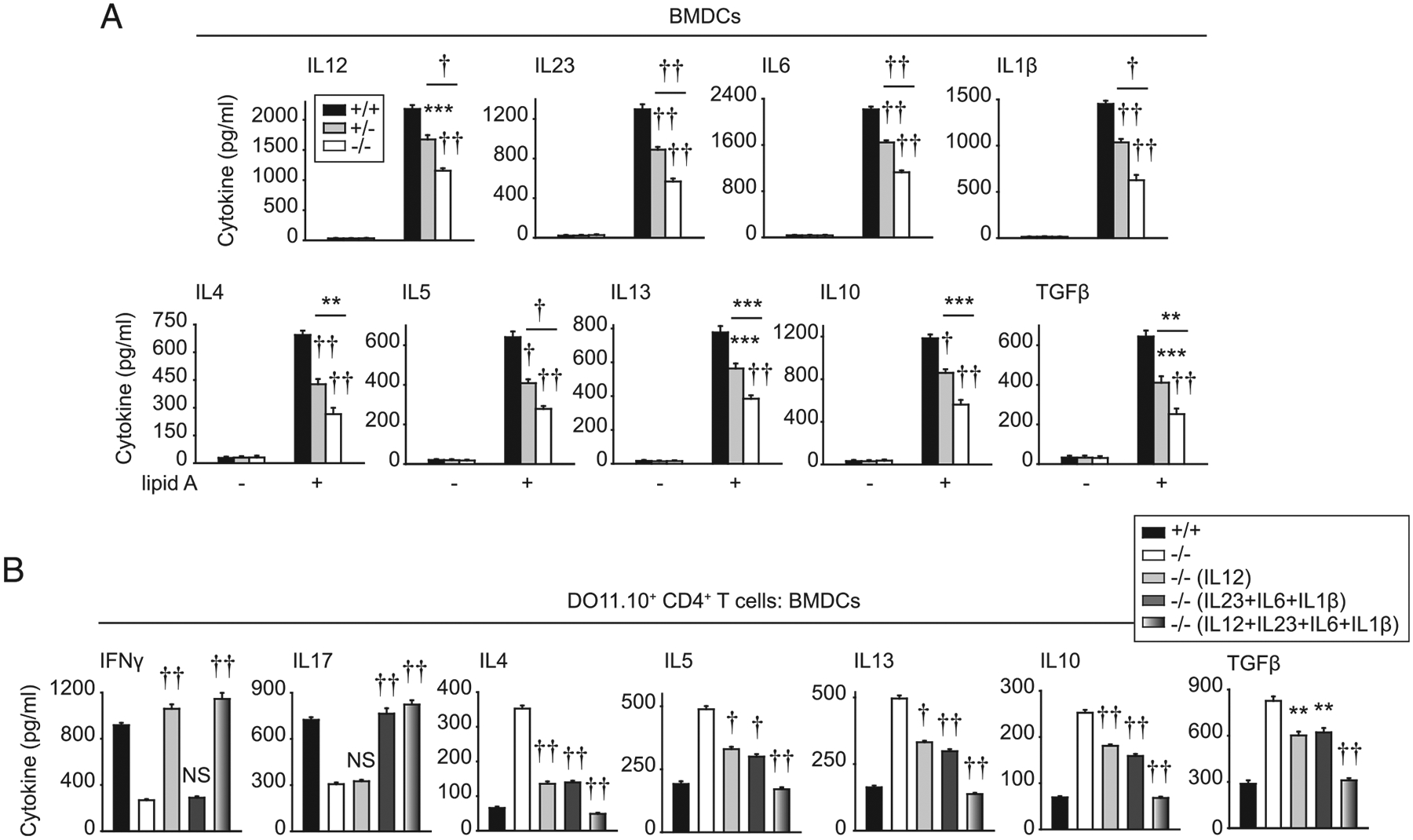

IRF5 in myeloid cells upregulates Th1- and Th17- conditioning cytokines

Given the decreased Th1 and Th17 differentiation and increased Th2 and Treg differentiation observed upon coculture of CD4+ T cells with Irf5−/− APCs, we sought to address mechanisms mediating these outcomes. We therefore assessed cytokines secreted from Irf5−/− APCs upon TLR4 stimulation. As has been previously reported in myeloid cells (2, 13, 15, 16) and consistent with the reduced Th1 and Th17 differentiation, TLR4-induced IL-12 (Th1 conditioning) and IL-23, IL-6, and IL-1β (Th17 conditioning) were reduced from Irf5−/− BMDCs compared with Irf5+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 8A). TLR4-induced IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (Th2-associated) and IL-10 and TGF-β (Treg conditioning) secretion was also reduced in Irf5−/− BMDCs (Fig. 8A). Therefore, the increased Th2 and Treg differentiation upon coculture with Irf5−/− BMDCs is not due to an increase in these cytokines from BMDCs. Of note is that IRF5 in BMMs demonstrated a similar contribution to the various in vitro measures assessed, including to TLR4-induced costimulatory molecule upregulation and cytokine secretion and in promoting T cell proliferation and differentiation in coculture (Supplemental Fig. 2C–F).

FIGURE 8.

Complementation of reduced Irf5−/− BMDC cytokines restores CD4+ T cell cytokine patterns. (A) BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h. Cytokines (eight replicates per group from two of three independent experiments). (B) BMDCs from Irf5+/+ or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h and then cocultured with OVA, DO11.10 CD4+ T cells ± IL-12 or IL-23/IL-1β/IL-6, alone or in combination, for 72 h (seven to eight replicates per group from two independent experiments). Cytokines. Significance is to Irf5+/+ BMDCs or as indicated in (A) or to Irf5−/− BMDCs without added cytokines for (B). Mean + SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

Given the reduced Th1- and Th17-conditioning cytokines from Irf5−/− BMDCs, we assessed if complementing the reduced cytokines observed from these cells could restore T cell differentiation during coculture with Irf5−/− BMDCs. Upon adding IL-12 during coculture of Irf5−/− BMDCs with WT DO11.10 CD4+ T cells and OVA, the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was restored to the levels of that observed with Irf5+/+ BMDC coculture (Fig. 8B). In contrast, IL-17 was not restored (Fig. 8B), demonstrating specificity of the IL-12 effects. With complementing the Th17- conditioning cytokines IL-23, IL-1β, and IL-6 in combination, IL-17 secretion was restored (Fig. 8B). In contrast, IFN-γ secretion was not restored under these conditions (Fig. 8B). With complementation of either of these Th1- or Th17-inducing cytokine conditions, the high levels of Th2 and Treg cytokines were reduced upon T cell coculture with Irf5−/− BMDCs (Fig. 8B). Moreover, with complementation of these Th1- and Th17- conditioning BMDC-derived cytokines in combination, Th1 and Th17 cytokines were increased, and Th2 and Treg cytokines were reduced to an even greater degree upon Irf5−/− BMDC/T cell coculture (Fig. 8B). Therefore, IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for the secretion of Th1- and Th17-conditioning cytokines, which, in turn, promote Th1 and Th17 differentiation and suppress Th2 and Treg differentiation.

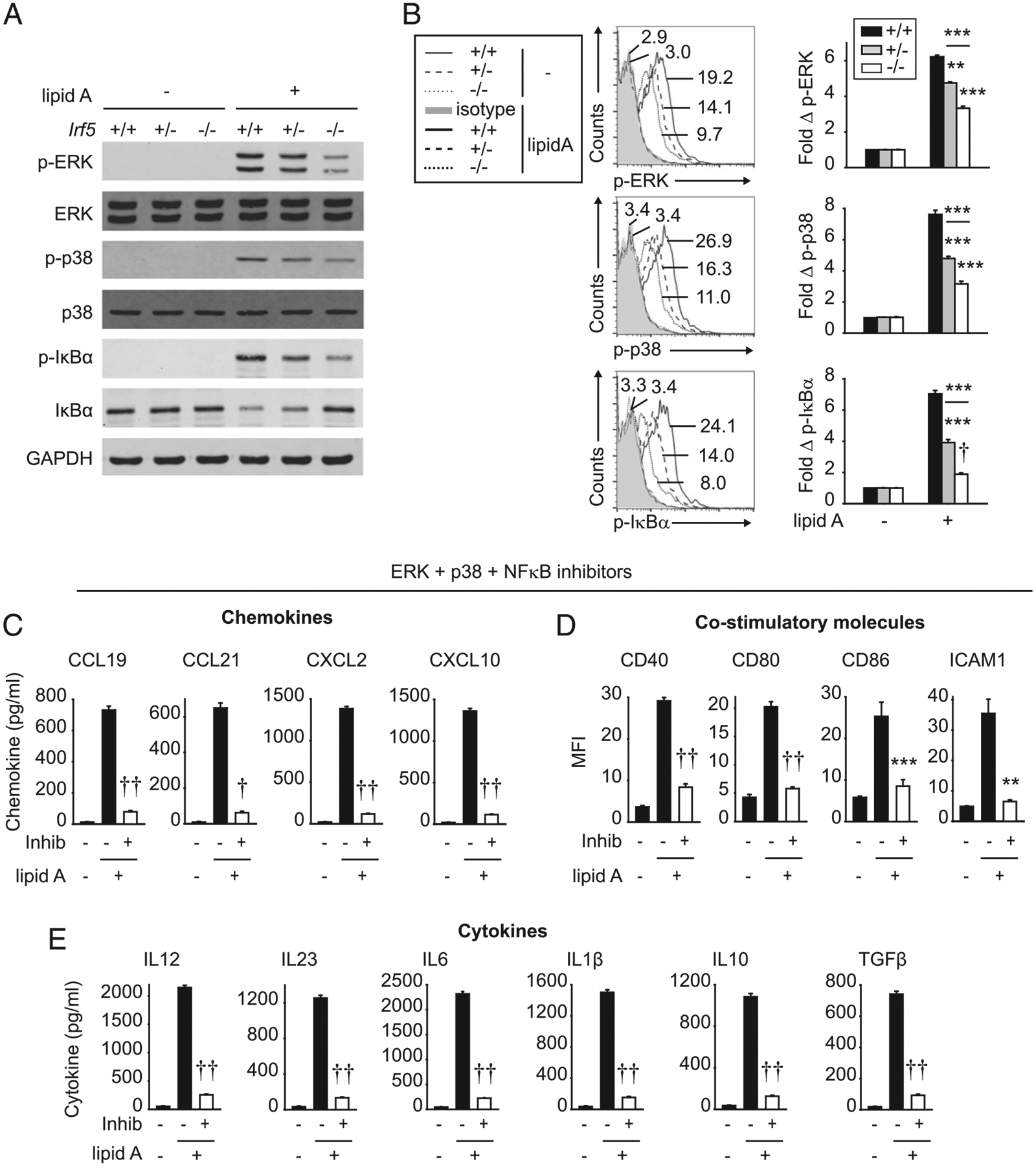

IRF5 promotes TLR4-induced proximal signaling pathways in myeloid cells, which, in turn, regulate pathways leading T cell outcomes

We next sought to assess additional IRF5-dependent mechanisms regulating the myeloid cell outcomes defined, including chemokine secretion, costimulatory molecule upregulation, and cytokine secretion. IRF5 was initially focused on for its role as a transcription factor, and we found that IRF5 bound to the promoters of the chemokine and costimulatory genes we had defined to be IRF5 dependent in BMDCs (Figs. 3E, 5C); IRF5 has been previously identified to bind to the promoters of a range of cytokines in myeloid cells (13, 15, 22, 23). Studies have also found that IRF5 can form a complex with IRAK1 and TRAF6 (15, 30, 31) and enhance PRR-induced MAPK and NF-κB signaling in human macrophages (2, 16). In contrast, IRF5 did not contribute to MAPK activation in mouse B cells (15). To our knowledge, an IRF5 requirement for PRR-induced MAPK signaling in mouse myeloid cells has not been reported. As expected, lipid A treatment induced MAPK (ERK and p38) and NF-κB (IκBα) pathway activation, as assessed by both Western blot (Fig. 9A) and flow cytometry (Fig. 9B). This activation was reduced in Irf5−/− BMDCs compared with Irf5+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 9A, 9B). Irf5+/− BMDCs demonstrated an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 9A, 9B). Moreover, inhibiting each of these pathways alone (Supplemental Fig. 3A–C), and particularly in combination (Fig. 9C–E), reduced TLR4-induced chemokine secretion, costimulatory molecule expression, and cytokine secretion, thereby establishing the importance of each of these signaling pathways in the IRF5-dependent outcomes identified. Cell survival was unimpaired with the inhibitors under these conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3D). Taken together, IRF5 is required for TLR4-induced MAPK and NF-κB activation, which, in turn, regulates multiple myeloid cell outcomes that then regulate T cells, including chemokine secretion, costimulatory molecule upregulation, and cytokine secretion.

FIGURE 9.

IRF5 is required for optimal levels of TLR4-induced MAPK and NF-κB pathways, which, in turn, regulate TLR4-mediated BMDC outcomes. (A and B) BMDCs from Irf5+/+, Irf5+/−, or Irf5−/− mice were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 15 min: (A) MAPK and NF-κB activation by Western blot. (B) Fold change phospho-MAPK and −IκBα by flow cytometry (three replicates per group; representative of two independent experiments). Representative flow cytometry for untreated cells shown with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for only Irf5+/+ BMDCs because of overlapping values. (C–E) WT BMDCs were cultured with a combination of an ERK inhibitor (Inhib) (PD98059), a p38 Inhib (SB202190), and an NF-κB Inhib (BAY 11–7082), or control vehicle for 1 h, and then treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 24 h. (C) Chemokines (six replicates per group from two independent experiments). (D) Costimulatory molecules (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) (seven replicates per group from two independent experiments). (E) Cytokines (six replicates per group from two independent experiments). Mean + SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

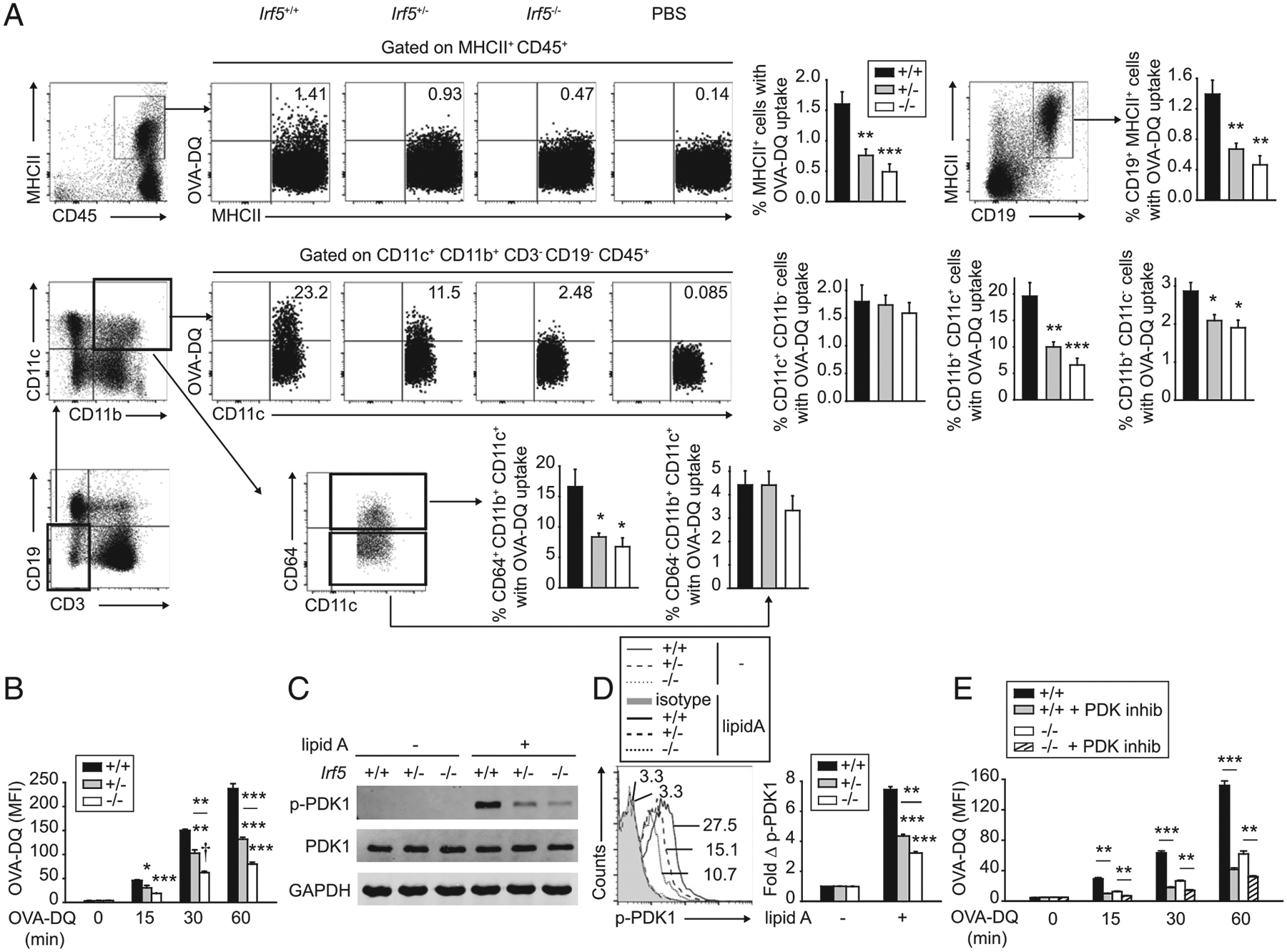

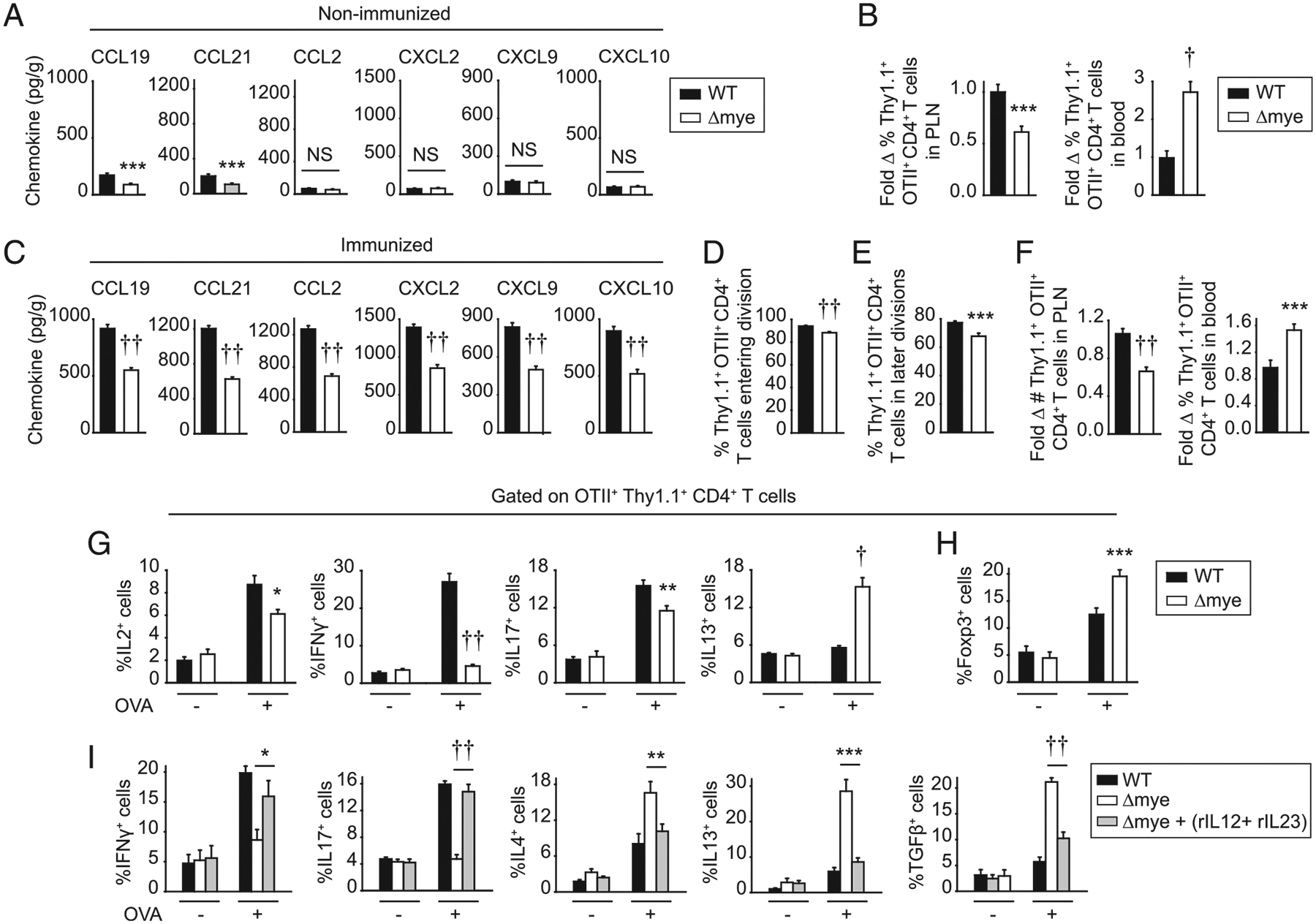

Myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 promotes T cell trafficking, proliferation, and differentiation in vivo

To determine if myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 was regulating each of the CD4+ T cell outcomes that we had identified in Irf5−/− mice in vivo and in studies in vitro (in the presence of either BMDCs or BMMs), we crossed LysM-Cre to Irf5fl/fl mice (Irf5Δmye mice). We confirmed that IRF5 was deleted from both Irf5Δmye BMDCs and BMMs (Supplemental Fig. 4A). IRF5 expression in Irf5Δmye skin fibroblasts was unaffected (Supplemental Fig. 4A), thereby demonstrating selectively in IRF5 deletion in these conditional mice. We first examined mechanisms regulating trafficking. Baseline homeostatic chemokine levels (CCL19 and CCL21) in PLN of Irf5Δmye mice were reduced (Fig. 10A), similar to findings in Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 2C). Consistently, trafficking of adoptively transferred naive WT OTII CD4+ T cells (which depends on homeostatic chemokines) to PLN of Irf5Δmye mice was reduced, whereas the frequency of these cells was increased in the blood of Irf5Δmye mice (Fig. 10B). Whereas nonhomeostatic chemokines were expressed at low levels and not different in PLN of nonimmunized Irf5fl/fl and Irf5Δmye mice (Fig. 10A), in Irf5Δmye mice adoptively transferred with OTII CD4+ T cells and then immunized with s.c. OVA/LPS, levels of multiple chemokines in PLN were not as effectively induced as in PLN of Irf5fl/fl mice (Fig. 10C), also similar to findings in Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 10.

Myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 regulates CD4+ T cell trafficking, proliferation, and differentiation in vivo. (A) Chemokine expression in PLN of Irf5fl/fl (WT) or Irf5Δmye mice (n = 14–17 per group from two independent experiments). (B) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5fl/fl or Irf5Δmye mice. Sixteen hours later, PLN were harvested. Percentage of Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells (n = 14 per group from two independent experiments). Percentage of Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells in blood is shown as a control. (C–H) CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5fl/fl or Irf5Δmye mice. Mice were immunized with s.c. 25 μg OVA/25 μg LPS. (C) Chemokine expression in PLN 24 h later (n = 14–17 per group from two independent experiments). (D–H) PLN were harvested 3 d after immunization. Summary graphs of OTII CD4+ T cells: (D) entering division, (E) in later divisions, and (F) number accumulated (n = 14–16 per group from three independent repeats). Frequency OTII CD4+ T cells in blood was examined as a control (n = 10 per group from two independent experiments). (G and H) PLN cells were restimulated with 2 μg/ml OVA peptide (323–339) for 12 h. (G) Percentage of cytokine-producing Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells (n = 6 per group). (H) Percentage of Foxp3-expressing Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells (n = 10–11 per group from two independent experiments). (I) Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into Thy1.2+ Irf5fl/fl or Irf5Δmye mice. Twenty-four hours later, mice were injected i.v. with IL-12/Fc and IL-23/Fc or Fc isotype control 1 h before immunization with s.c. 25 μg OVA/25 μg LPS. Percentage of cytokine-producing Thy1.1+ OTII CD4+ T cells 3 d later (n = 7–9 per group from two of three independent experiments). Mean + SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

We next examined the myeloid cell–intrinsic role for IRF5 in T cell proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Upon s.c. OVA/LPS immunization of Irf5Δmye mice adoptively transferred with WT OTII CD4+ T cells, CD4+ T cell entry and progression through cell divisions were reduced (Fig. 10D, 10E). Consistently, accumulation of OTII CD4+ T cells in PLN of recipient Irf5Δmye mice under these conditions was reduced, whereas the frequency of OTII CD4+ T cells in blood was increased compared with Irf5fl/fl mice (Fig. 10F). Consistent with the reduced proliferation, the frequency of IL-2–producing OTII CD4+ T cells was reduced in recipient Irf5Δmye mice (Fig. 10G). Similar to observations in Irf5−/− mice (Fig. 1F), the frequency of IFN-γ– and IL-17– producing OTII CD4+ T cells was reduced, whereas the frequency of IL-13 (Th2)–producing OTII CD4+ T cells was increased in PLN of recipient Irf5Δmye mice compared with Irf5fl/fl mice (Fig. 10G). Also similar to Irf5−/− mice, Foxp3-expressing OTII CD4+ T cells in recipient Irf5Δmye PLN were increased (Fig. 10H). As expected, by days 5 and 7 after immunization, OTII CD4+ T cells had fully entered and progressed through measurable cell divisions in both recipient Irf5fl/fl and Irf5Δmye mice (Supplemental Fig. 4B). However, the altered pattern of cytokine-producing OTII CD4+ T cells in immunized recipient Irf5Δmye compared with Irf5fl/fl mice persisted (Supplemental Fig. 4C).

To clearly establish the role of myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 Th1- and Th17-conditioning cytokines in the T cell differentiation outcomes in vivo, we complemented deficient cytokines by injecting IL-12/Fc and IL-23/Fc at the time of OVA/LPS immunization of Irf5Δmye mice adoptively transferred with OTII CD4+ T cells. The frequency of IFN-γ– and IL-17–producing OTII CD4+ T cells increased, whereas the frequency of IL-4–, IL-13–, and TGF-β–producing OTII CD4+ T cells decreased in draining PLN of these immunized IrfF5Δmye mice (Fig. 10I). Taken together, myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 is required for optimal levels of chemokine production both at baseline and upon activation, and, in turn, T cell trafficking to lymph nodes as well as for optimal CD4+ T cell proliferation and differentiation in vivo.

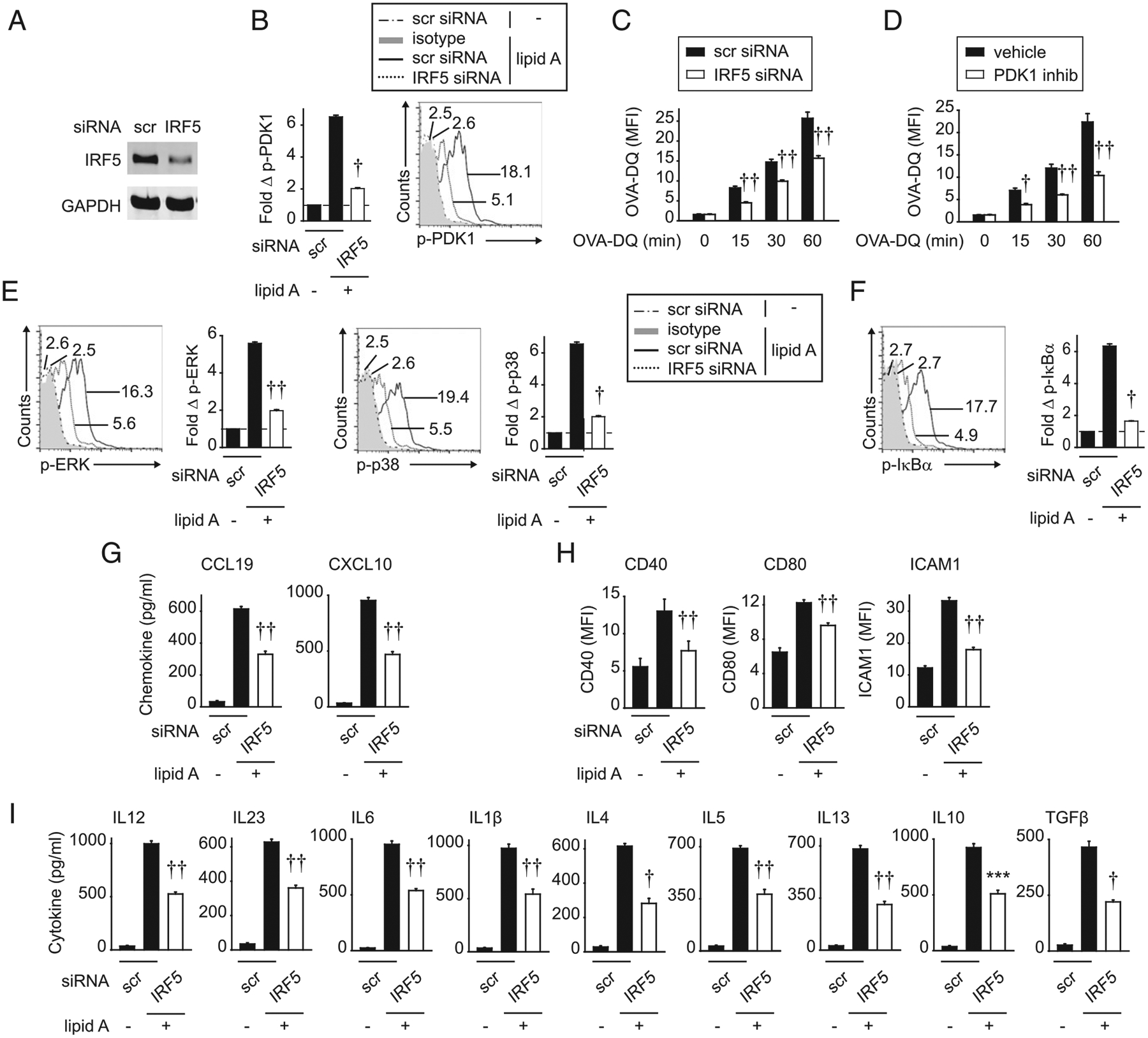

IRF5 is required for TLR4-induced costimulatory molecules and chemokine and cytokine secretion in human MDDCs

We next assessed if the IRF5-dependent outcomes we had identified in mouse BMDCs were similarly regulated by IRF5 in human MDDCs. For these studies, we reduced IRF5 in MDDCs using siRNA (Fig. 11A). As was observed in mouse BMDCs, both TLR4-induced PDK1 activation (Fig. 11B) and Ag uptake (OVA- DQ) (Fig. 11C) were reduced upon IRF5 knockdown in human MDDCs. Moreover, PDK1 inhibition reduced Ag uptake in MDDCs (Fig. 11D). TLR4-induced MAPK (Fig. 11E) and NF-κB (Fig. 11F) pathway activation was also reduced upon IRF5 knockdown in human MDDCs. Furthermore, IRF5 knockdown resulted in reduced TLR4-induced chemokine secretion, costimulatory molecule upregulation, and T cell–conditioning cytokine secretion from MDDCs (Fig. 11G–I). Therefore, IRF5 regulates multiple critical functions in human dendritic cells that ultimately regulate T cell outcomes.

FIGURE 11.

IRF5 in human MDDCs is required for Ag uptake and lipid A–induced chemokines, costimulatory molecules, and cytokines. Human MDDCs were transfected with scrambled or IRF5 siRNA. (A) IRF5 expression was assessed by Western blot. (B) Cells were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A for 15 min. Fold phospho-PDK1 induction by flow cytometry (n = 4 donors; representative of two independent experiments). (C) Cells were cocultured with 10 μg/ml OVA-DQ and assessed for Ag uptake at the indicated times (mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) (n = 12 donors from three independent experiments). (D) MDDCs were treated with GSK 2334470 (PDK1 inhibitor) (or vehicle control) for 1 h and then cocultured with OVA-DQ and assessed for OVA-DQ uptake at the indicated times (MFI) (n = 12 donors from three independent experiments). (E–H) MDDCs were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A and assessed for (E and F) fold phospho-protein induction at 15 min by flow cytometry (n = 4 donors; two independent experiments). (G) Chemokines at 24 h (n = 12 donors from three independent experiments). (H) Costimulatory molecules at 24 h (MFI) (n = 8 donors from two of three independent experiments). (I) Cytokines at 24 h (n = 12 donors from three independent experiments). Mean + SEM. ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5. Scr, scrambled.

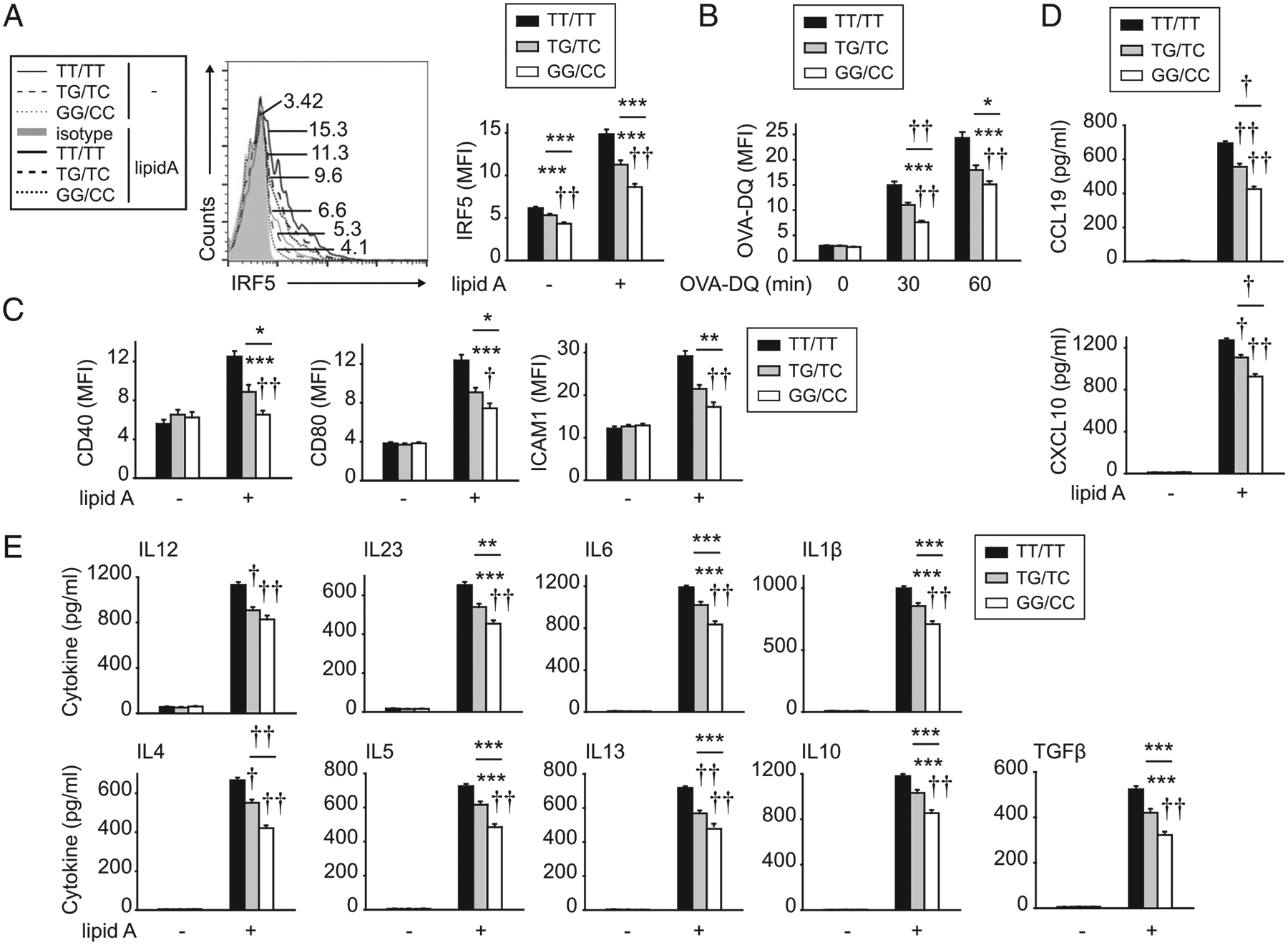

MDDCs from immune-mediated disease risk IRF5 rs2004640/rs2280714 TT/TT carriers show increased Ag uptake and TLR4-induced costimulatory molecules and chemokine and cytokine secretion relative to GG/CC carriers

We next hypothesized that myeloid cells from immune-mediated disease risk rs2004640/rs2280714 TT/TT (in the IRF5 region) carriers would show an increase in each of the IRF5-dependent outcomes we had defined. TT/TT carrier EBV-transformed B cells and PBMCs show increased IRF5 mRNA (1) and TT/TT carrier monocyte-derived macrophages show increased protein expression relative to GG/CC carriers (2). We confirmed that IRF5 protein expression was increased in disease risk rs2004640/rs2280714 TT/TT MDDCs, both at baseline and upon TLR4 stimulation when IRF5 expression is enhanced (Fig. 12A). Importantly, rs2004640/rs2280714 TT/TT carrier MDDCs demonstrated increased OVA-DQ uptake and TLR4-induced costimulatory molecules and chemokine and cytokine secretion compared with GG/CC carrier MDDCs (Fig. 12B–E). MDDCs from rs2004640/rs2280714 TG/TC carriers demonstrated an intermediate phenotype (Fig. 12). Therefore, MDDC functions regulating T cell outcomes are modulated by IRF5 immune-mediated disease risk genotype.

FIGURE 12.

MDDCs from IRF5 immune-disease risk variants demonstrate increased Ag uptake and TLR4-induced costimulatory molecules, chemokines, and cytokines. MDDCs were generated from rs2004640/rs2280714 TT/TT, TG/TC, or GG/CC carriers (n = 10 per genotype). (A and C–E) MDDCs were treated with 0.1 μg/ml lipid A and assessed 24 h later for (A) IRF5 expression. Representative flow cytometry with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values and summary graph of MFI. (C) Costimulatory molecules (MFI). (D) Chemokines. (E) Cytokines. (B) Cells were cocultured with 10 μg/ml OVA-DQ and assessed for Ag uptake at the indicated times (MFI). Mean + SEM. Significance is to TT/TT carrier MDDCs or as indicated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, †p < 1 × 10−4, ††p < 1 × 10−5.

Discussion

This study defines multiple distinct checkpoints through which T cell–extrinsic IRF5 regulates T cell outcomes in vivo and defines signaling pathways and mechanisms through which IRF5 mediates these effects. It finds that IRF5 promotes expression in lymph nodes of both homeostatic chemokines and chemokines induced during an immune response and, in turn, the trafficking of T cells to lymph nodes. IRF5 further promotes Ag presentation in myeloid cells through PDK1-dependent soluble Ag uptake and induction of costimulatory molecules. Moreover, IRF5 in myeloid cells is required for TLR4-induced secretion of Th1 (IL-12)– and Th17 (IL-23, IL-6, and IL-1β)–conditioning cytokines, which lead to induction of Th1 and Th17 cells and through cross-regulatory mechanisms, the attenuation of Th2 and Treg cells. IRF5 promotes TLR4-induced MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, which, in turn, are required for these IRF5-dependent myeloid cell pathways. Further, IRF5 is enriched at the promoters of various TLR4- induced, IRF5-dependent genes. IRF5 deletion in myeloid cells in vivo demonstrates similar T cell outcomes to those observed in Irf5−/− mice, thereby highlighting a myeloid cell–intrinsic role for IRF5 in T cell regulation in vivo. Importantly, complementing Th1- and Th17-conditioning cytokines can restore T cell differentiation patterns in the context of IRF5-deficient myeloid cells in vitro and in vivo. IRF5 in human MDDCs is similarly required for the APC-dependent outcomes observed in mouse myeloid cells, and MDDCs from IRF5 genetic variant carriers leading to increased IRF5 expression and conferring risk for immune-mediated diseases have an increase in the various IRF5- dependent APC outcomes identified. Therefore, our studies highlight that IRF5 in myeloid cells promotes T cell activation and differentiation through regulation of multiple distinct checkpoints (Supplemental Fig. 4E) and that IRF5 disease-associated genetic variants modulate these outcomes.

To our knowledge, a role for IRF5 in mediating T cell trafficking to lymph nodes has not been reported. We found that IRF5 was required for optimal expression in lymph nodes of both homeostatic chemokines and chemokines induced during immunization and, in turn, for promoting T cell recruitment to lymph nodes. Myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 was sufficient to mediate these effects in vivo. IRF5 has been previously shown to contribute to induction of select chemokines in BAL in LPS-treated mice (8) and in the peritoneal cavity with pristine injection (6), with contributions of IRF5 to accumulation of certain cell subsets in these tissues (6, 8). We now identify that myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 is required for chemokine expression directly in lymph nodes in which immune responses are initiated. Although these studies clearly identify myeloid cells as important producers of chemokines regulating T cell recruitment to lymph nodes, IRF5 in additional cell subsets may also be contributing to T cell trafficking to lymph nodes, such as in stromal cells in which IRF5 is also expressed (32).

IRF5 in myeloid cells has been previously shown to regulate increased Th1 and Th17 differentiation and decreased Th2 differentiation in vitro (9, 13) and in vivo (7, 10, 11). We now extend these findings and define mechanisms contributing to these outcomes. Both Th1 and Th17 cells can cross-regulate Th2 differentiation (33), and we now find that complementation of the deficient Th1 (IL-12)– and Th17 (IL-23)–conditioning cytokines from Irf5−/− myeloid cells can restore Th1 and Th17 cells and reduce Th2 and Treg cells both in vitro and in vivo. The restoration in vivo was partial, likely in part because of complementation of only IL-12 and IL-23, whereas we conducted in vitro complementation with IL-12, IL-23, IL-1β, and IL-6, which were all deficient in Irf5−/− myeloid cells, and this led to more complete restoration. Moreover, we now find that myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 reduces Treg differentiation and that this is similarly in part due to cross-regulatory mechanisms through IRF5-dependent Th1 and Th17 conditioning cytokines. The increased Tregs were not due to increased IL-10 or TGF-β secretion from Irf5−/− myeloid cells, although some (13), but not all, studies (2, 34) have reported increased IL-10 in Irf5−/− myeloid cells. The IRF5-dependent IL-10 regulation in myeloid cells may also vary based on tissue site (e.g., intestine) (10). The level of Ag presentation can also modulate T cell differentiation (35), and we now find that IRF5 contributes to Ag presentation through the ability to regulate PDK1-dependent soluble Ag uptake and induction of costimulatory molecules. A prior study had identified that IRF5 can regulate CD40 induction in myeloid cells (M2 macrophages) (13), and we now find that IRF5 can regulate additional costimulatory molecules, including CD80, CD86, and ICAM1. We also find that consistent with the IRF5-dependent Ag presentation mechanisms we identify, myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 promotes IL-2 production from T cells, which, in turn, promotes T cell proliferation. That IRF5 promotes Th1 and Th17 differentiation while suppressing not only Th2 but also Treg differentiation provides a basis for a highly proinflammatory environment consistent with the multiple immune-mediated diseases that IRF5 is associated with.

We observed that IRF5 in myeloid cells regulates early (at 15 min) PRR-initiated MAPK, NF-κB, and PDK1 signaling pathways, which are important for the various IRF5-dependent checkpoints identified. Consistent with the ability to modulate these early signaling pathways, IRF5 undergoes rapid phosphorylation with PRR stimulation (2, 22, 36) and associates with signaling complexes assembled upon PRR stimulation (2, 15, 30, 31), thereby highlighting a potential scaffolding role for IRF5. Importantly, at later times after PRR stimulation (4 h), IRF5 translocates to the nucleus (2, 37), where it can function as a transcription factor; we observed IRF5 enrichment at the promoters of various genes regulating these checkpoints at this later time point. These studies highlight distinct cytoplasmic and nuclear functions for IRF5, which differ in their kinetics.

In this study, we define multiple distinct checkpoints through which myeloid cell–intrinsic IRF5 regulates T cell activation and differentiation, along with IRF5-dependent signaling pathways and mechanisms through which these checkpoints are regulated. Recent preclinical studies have demonstrated that delivery systems targeting IRF5 during inflammatory processes in vivo can improve outcomes. For example, nanoparticle-delivered IRF5 siRNA during acute myocardial infarction improved infarct healing (38) and during spinal cord injury reduced adverse outcomes and promoted functional recovery (39). Our findings therefore provide additional insight into the mechanisms through which the IRF5 genetic variants leading to increased IRF5 expression confer increased risk for immune-mediated diseases and into potential approaches for therapeutically targeting IRF5 so as to favorably restore T cell regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01AI120369 and R01DK099097 and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this article:

- BMDC

bone marrow–derived dendritic cell

- BMM

bone marrow–derived macrophage

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- MDDC

monocyte-derived dendritic cell

- PLN

peripheral lymph node

- PRR

pattern-recognition receptor

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Treg

regulatory T

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Graham RR, Kozyrev SV, Baechler EC, Reddy MV, Plenge RM, Bauer JW, Ortmann WA, Koeuth T, González Escribano MF, Pons-Estel B, et al. ; Argentine and Spanish Collaborative Groups. 2006. A common haplotype of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) regulates splicing and expression and is associated with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet 38: 550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedl M, Yan J, and Abraham C. 2016. IRF5 and IRF5 disease-risk variants increase glycolysis and human M1 macrophage polarization by regulating proximal signaling and Akt2 activation. Cell Rep 16: 2442–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, et al. ; International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC). 2012. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491: 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eames HL, Corbin AL, and Udalova IA. 2016. Interferon regulatory factor 5 in human autoimmunity and murine models of autoimmune disease. Transl. Res 167: 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng D, Yang L, Bi X, Stone RC, Patel P, and Barnes BJ. 2012. Irf5-deficient mice are protected from pristane-induced lupus via increased Th2 cytokines and altered IgG class switching. Eur. J. Immunol 42: 1477–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y, Lee PY, Li Y, Liu C, Zhuang H, Han S, Nacionales DC, Weinstein J, Mathews CE, Moldawer LL, et al. 2012. Pleiotropic IFN-dependent and -independent effects of IRF5 on the pathogenesis of experimental lupus. J. Immunol 188: 4113–4121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne AJ, Weiss M, Mathie SA, Walker SA, Eames HL, Saliba D, Lloyd CM, and Udalova IA. 2017. A critical role for IRF5 in regulating allergic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 10: 716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss M, Byrne AJ, Blazek K, Saliba DG, Pease JE, Perocheau D, Feldmann M, and Udalova IA. 2015. IRF5 controls both acute and chronic inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 11001–11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oriss TB, Raundhal M, Morse C, Huff RE, Das S, Hannum R, Gauthier MC, Scholl KL, Chakraborty K, Nouraie SM, et al. 2017. IRF5 distinguishes severe asthma in humans and drives Th1 phenotype and airway hyperreactivity in mice. JCI Insight 2: e91019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey SP, Yan J, Turner JR, and Abraham C. 2019. Reducing IRF5 expression attenuates colitis in mice, but impairs the clearance of intestinal pathogens. [Published erratum appears in 2019 Mucosal Immunol. 12: 1065.] Mucosal Immunol 12: 874–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalmas E, Toubal A, Alzaid F, Blazek K, Eames HL, Lebozec K, Pini M, Hainault I, Montastier E, Denis RG, et al. 2015. Irf5 deficiency in macrophages promotes beneficial adipose tissue expansion and insulin sensitivity during obesity. Nat. Med 21: 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paun A, Bankoti R, Joshi T, Pitha PM, and Stäger S. 2011. Critical role of IRF-5 in the development of T helper 1 responses to Leishmania donovani infection. PLoS Pathog 7: e1001246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krausgruber T, Blazek K, Smallie T, Alzabin S, Lockstone H, Sahgal N, Hussell T, Feldmann M, and Udalova IA. 2011. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat. Immunol 12: 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z, Xu L, Li W, Jin X, Song X, Chen X, Zhu J, Zhou S, Li Y, Zhang W, et al. 2017. Innate scavenger receptor-A regulates adaptive T helper cell responses to pathogen infection. Nat. Commun 8: 16035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takaoka A, Yanai H, Kondo S, Duncan G, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Kano S, Honda K, Ohba Y, Mak TW, and Taniguchi T. 2005. Integral role of IRF-5 in the gene induction programme activated by toll-like receptors. Nature 434: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedl M, and Abraham C. 2012. IRF5 risk polymorphisms contribute to interindividual variance in pattern recognition receptor-mediated cytokine secretion in human monocyte-derived cells. J. Immunol 188: 5348–5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng S, and Abraham C. 2013. NF-kB1 inhibits NOD2-induced cytokine secretion through ATF3-dependent mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol 33: 4857–4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn MD, Tangemann K, Tam C, Cyster JG, Rosen SD, and Williams LT. 1998. A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Förster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Müller I, Wolf E, and Lipp M. 1999. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunn MD, Kyuwa S, Tam C, Kakiuchi T, Matsuzawa A, Williams LT, and Nakano H. 1999. Mice lacking expression of secondary lymphoid organ chemokine have defects in lymphocyte homing and dendritic cell localization. J. Exp. Med 189: 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell JJ, Bowman EP, Murphy K, Youngman KR, Siani MA, Thompson DA, Wu L, Zlotnik A, and Butcher EC. 1998. 6-C-kine (SLC), a lymphocyte adhesion-triggering chemokine expressed by high endothelium, is an agonist for the MIP-3beta receptor CCR7. J. Cell Biol 141: 1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes BJ, Moore PA, and Pitha PM. 2001. Virus-specific activation of a novel interferon regulatory factor, IRF-5, results in the induction of distinct interferon alpha genes. J. Biol. Chem 276: 23382–23390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saliba DG, Heger A, Eames HL, Oikonomopoulos S, Teixeira A, Blazek K, Androulidaki A, Wong D, Goh FG, Weiss M, et al. 2014. IRF5:RelA interaction targets inflammatory genes in macrophages. Cell Rep 8: 1308–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langlet C, Tamoutounour S, Henri S, Luche H, Ardouin L, Grégoire C, Malissen B, and Guilliams M. 2012. CD64 expression distinguishes monocyte-derived and conventional dendritic cells and reveals their distinct role during intramuscular immunization. J. Immunol 188: 1751–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min J, Yang D, Kim M, Haam K, Yoo A, Choi JH, Schraml BU, Kim YS, Kim D, and Kang SJ. 2018. Inflammation induces two types of inflammatory dendritic cells in inflamed lymph nodes. [Published erratum appears in 2018 Exp. Mol. Med. 50: 33.] Exp. Mol. Med 50: e458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, Shen Y, Du J, Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY, et al. 2008. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature 453: 236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voo KS, Wang YH, Santori FR, Boggiano C, Wang YH, Arima K, Bover L, Hanabuchi S, Khalili J, Marinova E, et al. 2009. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 4793–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu M, Pokrovskii M, Ding Y, Yi R, Au C, Harrison OJ, Galan C, Belkaid Y, Bonneau R, and Littman DR. 2018. c-MAF-dependent regulatory T cells mediate immunological tolerance to a gut pathobiont. [Published erratum appears in 2019 Nature 566: E7.] Nature 554: 373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch MA, Tucker-Heard G, Perdue NR, Killebrew JR, Urdahl KB, and Campbell DJ. 2009. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat. Immunol 10: 595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paun A, Reinert JT, Jiang Z, Medin C, Balkhi MY, Fitzgerald KA, and Pitha PM. 2008. Functional characterization of murine interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF-5) and its role in the innate antiviral response. J. Biol. Chem 283: 14295–14308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inoue M, Arikawa T, Chen YH, Moriwaki Y, Price M, Brown M, Perfect JR, and Shinohara ML. 2014. T cells down-regulate macrophage TNF production by IRAK1-mediated IL-10 expression and control innate hyperinflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 5295–5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saigusa R, Asano Y, Taniguchi T, Yamashita T, Ichimura Y, Takahashi T, Toyama T, Yoshizaki A, Sugawara K, Tsuruta D, et al. 2015. Multifaceted contribution of the TLR4-activated IRF5 transcription factor in systemic sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: 15136–15141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abraham C, and Cho JH. 2009. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med 361: 2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkins AA, Yasuda K, Wilson GE, Aprahamian T, Xie Y, Maganto-Garcia E, Shukla P, Oberlander L, Laskow B, Menn-Josephy H, et al. 2015. IRF5 deficiency ameliorates lupus but promotes atherosclerosis and metabolic dysfunction in a mouse model of lupus-associated atherosclerosis. J. Immunol 194: 1467–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, and Bottomly K. 1995. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med 182: 1591–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez-Pelaez M, Lamont DJ, Peggie M, Shpiro N, Gray NS, and Cohen P. 2014. Protein kinase IKKβ-catalyzed phosphorylation of IRF5 at Ser462 induces its dimerization and nuclear translocation in myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 17432–17437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang Foreman HC, Van Scoy S, Cheng TF, and Reich NC. 2012. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 5 by site specific phosphorylation. PLoS One 7: e33098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courties G, Heidt T, Sebas M, Iwamoto Y, Jeon D, Truelove J, Tricot B, Wojtkiewicz G, Dutta P, Sager HB, et al. 2014. In vivo silencing of the transcription factor IRF5 reprograms the macrophage phenotype and improves infarct healing. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 63: 1556–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Liu Y, Xu H, and Fu Q. 2016. Nanoparticle-delivered IRF5 siRNA facilitates M1 to M2 transition, reduces demyelination and neurofilament loss, and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. Inflammation 39: 1704–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.