Abstract

Background

The association between metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and disease progression in patients with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are unclear.

Aims

To explore the association between MAFLD and the severity of COVID-19 by meta-analysis.

Methods

We conducted a literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, Medline (OVID), and MedRxiv from inception to July 6, 2020. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and Stata 14.0 were used for quality assessment of included studies as well as for performing a pooled analysis.

Results

A total of 6 studies with 1,293 participants were included after screening. Four studies reported the prevalence of MAFLD patients with COVID-19, with a pooled prevalence of 0.31 for MAFLD (95CI 0.28, 0.35, I2 = 38.8%, P = 0.179). MAFLD increased the risk of COVID-19 disease severity, with a pooled OR of 2.93 (95CI 1.87, 4.60, I2 = 34.3%, P = 0.166).

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, we found that a high percentage of patients with COVID-19 had MAFLD. Meanwhile, MAFLD increased the risk of disease progression among patients with COVID-19. Thus, better intensive care and monitoring are needed for MAFLD patients infected by SARS-COV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Metabolic associated fatty liver disease

1. Introduction

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to more than 23 million confirmed cases and 800 thousand deaths worldwide as of August 24, 2020 (https://covid19.who.int/). Emerging data suggest that hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are highly prevalent among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, and that these may be associated with an increased risk of mortality due to the virus. Metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is a well-known risk factor for CVDs and diabetes, and has been closely related to mortality due to these diseases [1,2]. MAFLD was reported to affect approximately 20–30% of people worldwide [3], [4], [5]. Several studies demonstrated that MAFLD could increase disease severity in patients with COVID-19. However, Zhou et al. found that MAFLD was not significantly associated with a higher risk of disease severity in young patients [6]. Therefore, in order to clarify the role of MAFLD among patients with COVID-19, we conducted a meta-analysis to summarize the existing evidence about the pooled prevalence of MAFLD, as well as the association between MAFLD and disease severity among patients with COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We conducted a literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, Medline(OVID), and MedRxiv from inception to July 6, 2020. We used keywords and MeSH terms to retrieve potential suitable papers, including “SARS-COV-2”, “COVID-19”, “metabolic associated fatty liver disease”, “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)”, and “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)”. The detail of the search strategy used is shown in the Supplementary information.

2.2. Study selection

We screened the titles and abstracts of papers. For potential eligible papers, we obtained the full text. The progression of screening was determined independently by (Pan Lu and Xia Xie). Disagreements were resolved through further discussions or third-party arbitration.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

We included studies investigating the association between MAFLD and disease severity among patients with COVID-19. We excluded studies when it was a review or if the study was not in English. MAFLD was defined by criteria based on hepatic steatosis, in addition to meeting one of the following clinical parameters, such as being overweight, having type 2 diabetes mellitus, or exhibiting metabolic dysregulation [5,7]. All of studies evaluated the severity of COVID-19 according to the criteria in Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7). Patients were regarded as severe cases when they meet any of following conditions: (i)significantly increased respiration rate; (ii)hypoxia; (iii)consciousness disorders: apathy, somnolence, coma, and convulsions; (iv)food refusal or feeding difficulty and dehydration; (v)other manifestations: such as bleeding and coagulation disorders, myocardial damage, gastrointestinal dysfunction, raised level of liver enzyme, and rhabdomyolysis; (vi)critical cases [8].

2.4. Data extraction

Two authors (Xia Xie and Jiang Yuan) independently extracted the following information from the included studies: country, investigation time, age, study design, sample number, percentage of males, and prevalence of MAFLD.

2.5. Quality assessment of the included studies

Study quality was independently performed by (Jiachen Xu and Dawei Guo) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). The NOS scale for cross-sectional studies includes selection, comparability, and outcome. A high score indicates a high quality.

2.6. Statistical analysis

We performed pooled analysis using Stata 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A fixed effects model was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between MAFLD and disease severity among patients with COVID-19. Heterogeneity was examined using the I2 value and Cochran's Q test. A lower I2 value indicated lower heterogeneity. We also calculated the pooled prevalence of MAFLD among patients with COVID-19.

3. Results

3.1. Included studies

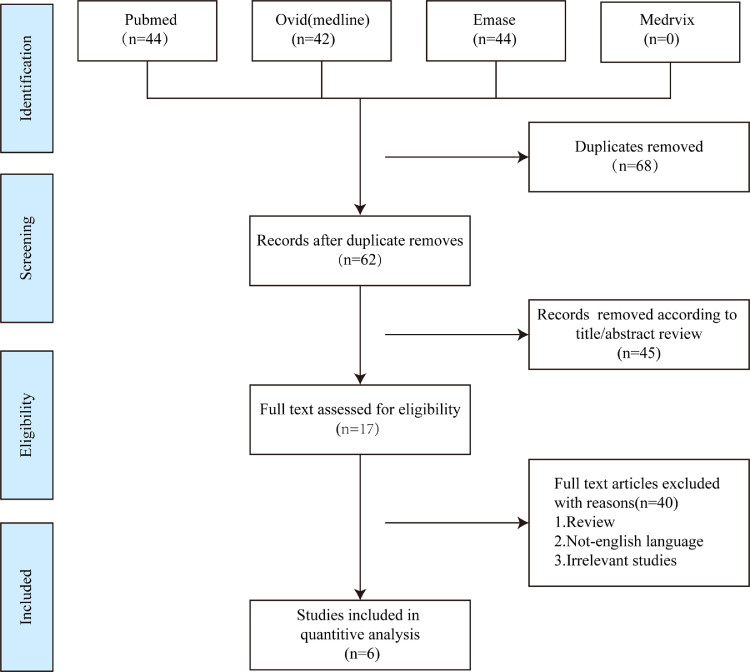

A total of 6 studies with 1293 participants were included after screening (Fig. 1 ) [1,6,[9], [10], [11], [12]. All of these studies were performed in China, and included four cross-sectional studies and two case-control studies (Table 1 ). All studies evaluated the severity of COVID-19 according to the criteria listed in the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 7). The NOS score ranged from 8 to 9 (Table S1–2).

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of research screening.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Region | Age | Sample | Study design | Male | MAFLD% | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou Y(a) 2020 | China | – | 327 | cross-sectional study | – | 28.4% | 9 |

| Zhou YJ(b) 2020 | China | 42.1 ± 11.4 | 101 | case-control study | 0.745 | – | 8 |

| Targher G 2020 | China | 47 | 310 | cross-sectional study | 0.481 | 30.3% | 8 |

| Ji D 2020 | China | 44.5(34.8–54.1) | 202 | cross-sectional study | 0.559 | 37.6% | 9 |

| Zheng K 2020 | China | 47 | 214 | cross-sectional study | 0.258 | 30.8% | 8 |

| Gao F 2020 | China | 46.0 ± 13.0 | 130 | case-control study | 0.631 | – | 9 |

Abbreviations:NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; MAFLD, Metabolic associated fatty liver disease;.

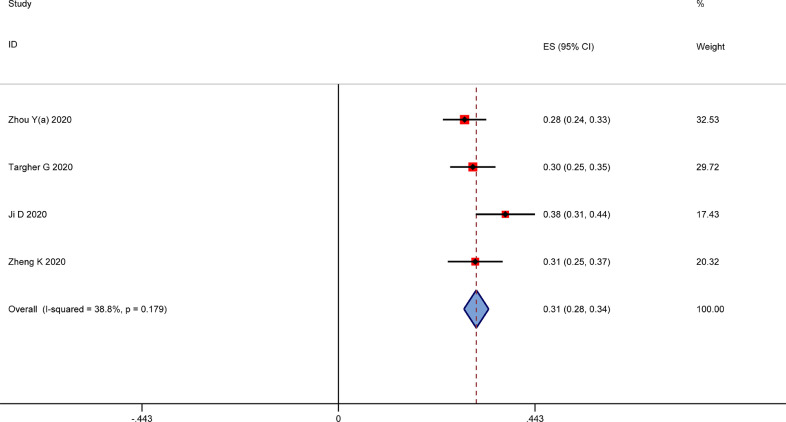

3.2. The pooled prevalence of MALFD among patients with COVID-19

Four studies reported the prevalence of MAFLD patients with COVID-19, with pooled prevalence of MAFLD found to be 0.31(95CI 0.28, 0.35, I2=38.8%, P = 0.179) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

The pooled prevalence of MAFLD among patients with COVID-19.

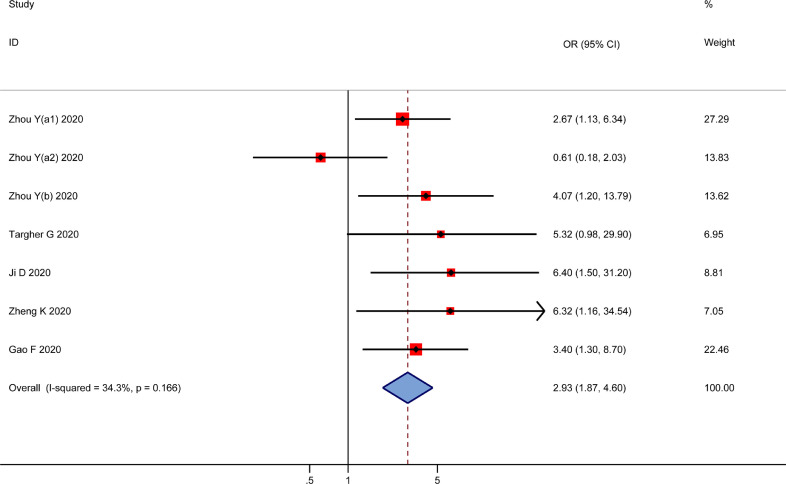

3.3. MALFD increases the risk of disease severity among patients with COVID-19

Six studies investigated the association between MAFLD and disease severity risk in patients with COVID-19. MAFLD increased the risk of COVID-19 disease severity, with a pooled OR of 2.93 (95CI 1.87, 4.60, I2=34.3%, P = 0.166) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

The association of MAFLD with disease severity among patients with COVID-19.

4. Discussion

In the present study, patients with COVID-19 had high percentage of MAFLD, with MAFLD found to increase the risk of disease progression in patients with COVID-19. MAFLD was defined by criteria based on hepatic steatosis, in addition to metabolic diseases, these studies had a high percentage among patients with COVID-19. For instance, Richardson et al. reported a prevalence of 41.7% for obesity and 33.8% for diabetes among 5700 patients with COVID-19 in New York [13]. Meanwhile, metabolic diseases were significantly associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 [14], [15], [16]. Recently, several meta-analyses demonstrated that diabetes and obesity were associated with increased risk for mortality and disease severity of COVID-19 [17,18].

For COVID-19 infection to occur, SARS-CoV-2 must bind to the host cell surface's ACE2 receptor, which initiates the host defense response and disease process [19,20]. The expression of ACE2 was higher in the animal model of hepatic steatosis [21], which may increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 entry into the hepatocytes, thus leading to liver injury. Meanwhile, liver injury was reported to be significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality among patients with COVID-19 [22], [23], [24]. In addition, patients with MAFLD were characterized by impaired hepatic innate immunity, such as having macrophage in polarization stages, as well as exhibiting increased levels of inflammatory mediators and cytokines [25,26]. Therefore, the status of inflammation associated with MAFLD further exacerbates the infection in patients with COVID-19 and can even lead to a cytokine storm, which greatly increases mortality risk.

There are several limitations in our present study. First, the sample number included studies which were small and conducted only in China, which may have affected the extrapolation of the results. Fortunately, we conducted retrieval of systematic references using several open databases and medRxiv. However, the results still need to be further validated using large-scale studies involving a variety of regions and races. Second, there were only six studies included in our final analysis, with only one study having a sub-group analysis, which may have impacted our pooled results. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the studies was reasonably acceptable, thus ensuring the reliability of outcomes in the studies. Finally, the included studies were cross-sectional studies and case-control studies, which are considered to be inferior to prospective cohort studies.

In conclusion, patients with COVID-19 had high percentage of MAFLD. In addition, MAFLD increased the risk of disease progression in patients with COVID-19. Thus, better intensive care and monitoring are needed for MAFLD patients infected by SARS-COV-2.

Sources of funding, grant support

None

Financial disclosure

None

Declaration of Competing Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

None

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dld.2020.09.007.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Gao F., Zheng K.I., Wang X.B., et al. Metabolic associated fatty liver disease increases coronavirus disease 2019 disease severity in nondiabetic patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jgh.15112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciardullo S., Monti T., Perseghin G. Prevalence of liver steatosis and fibrosis detected by transient elastography in adolescents in the 2017-2018 national health and nutrition examination survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou F., Zhou J., Wang W., et al. Unexpected rapid increase in the burden of NAFLD in China from 2008 to 2018: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2019;70:1119–1133. doi: 10.1002/hep.30702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J., Zhou F., Wang W., et al. Epidemiological features of NAFLD from 1999 to 2018 in China. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2020;71:1851–1864. doi: 10.1002/hep.31150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eslam M., Sanyal A.J., George J. MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1999–2014.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y.J., Zheng K.I., Wang X.B., et al. Younger patients with MAFLD are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness: a multicenter preliminary analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:719–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eslam M., Newsome P.N., Sarin S.K., et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miao H., Li H., Yao Y., et al. Update on recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis: Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03973-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Y.J., Zheng K.I., Wang X.B., et al. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease is associated with severity of COVID-19. Liver Int: Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2020 doi: 10.1111/liv.14575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Targher G., Mantovani A., Byrne C.D., et al. Detrimental effects of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on severity of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng K.I., Gao F., Wang X.B., et al. Letter to the Editor: obesity as a risk factor for greater severity of COVID-19 in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Metab Clin Exp. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji D., Qin E., Xu J., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. J Hepatol. 2020;73:451–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu L., She Z.G., Cheng X., et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021. 1068-77.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J., Hu J., Zhu C. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang I., Lim M.A., Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q., Zhang Y., Wu L., et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W., Li C., Liu B., et al. Pioglitazone upregulates hepatic angiotensin converting enzyme 2 expression in rats with steatohepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:892–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phipps M.M., Barraza L.H., LaSota E.D., et al. Acute liver injury in COVID-19: prevalence and association with clinical outcomes in a large US cohort. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.31404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei F., Liu Y.M., Zhou F., et al. Longitudinal association between markers of liver injury and mortality in COVID-19 in China. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.31301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazankov K., Jørgensen S.M.D., Thomsen K.L., et al. The role of macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:145–159. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musso G., Cassader M., Gambino R. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: emerging molecular targets and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:249–274. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.