Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has contributed to an increase in intimate partner violence (IPV), posing challenges to health care providers who must protect themselves and others during sexual assault examinations. Victims of sexual assault encountered in prehospital and emergency department (ED) settings have legal as well as medical needs. A series of procedures must be carefully followed to facilitate forensic evidence collection and law enforcement investigation. A literature review detected a paucity of published guidance on the management of sexual assault patients in the ED, and no information specific to COVID-19.

Objective

Investigators sought to update the San Diego County sexual assault guidelines, created in collaboration with health care professionals, forensic specialists, and law enforcement, through a consensus iterative review process. An additional objective was to create a SAFET-I Tool for use by frontline providers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

The authors present a novel SAFET-I Tool that outlines the following five components of effective sexual assault patient care: stabilization, alert system activation, forensic evidence consideration, expedited post-assault treatment, and trauma-informed care. This framework can be used as an educational tool and template for agencies interested in developing or adapting existing sexual assault policies.

Conclusions

There is a lack of clinical guidance for ED providers that integrates the many aspects of sexual assault patient care, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. A SAFET-I Tool is presented to assist emergency health care providers in the treatment and advocacy of sexual assault patients during a period with increasing rates of IPV.

Keywords: sexual assault, sexual assault examination, sexual assault guidelines, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, COVID-19, coronavirus, trauma-informed care, forensics

INTRODUCTION.

Sexual assault can affect people of any age or gender, with lasting effects on patients and their families. In addition to medical evaluation, patients require trauma-informed care, appropriate and timely post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and emotional support (1, 2, 3). Diverse groups can become involved in sexual assault cases, including physicians; specially trained forensic nurses; law enforcement; and patient advocates, such as social workers, case managers, Child Welfare Services (CWS), and Adult Protective Services personnel (4). An understanding of each group's role will facilitate better communication and improve patient care.

There is a paucity of literature directed toward emergency physicians, triage nurses, and health care staff that addresses the management of patients who are victims of sexual assault and includes PEP recommendations. To address this gap, San Diego County developed up-to-date, evidence-based guidance as a collaborative initiative between emergency, forensic, and law-enforcement experts. Subsequently, the investigators adapted the San Diego County guidelines and created a SAFET-I clinical management tool to assist and integrate emergency department (ED) health care providers into the workflow of forensic examiners. The SAFET-I Tool provides general, evidence-based guidance that can be incorporated into existing hospital, county, state, and national protocols.

This article presents the components of the SAFET-I framework for use by frontline health care professionals in the management of sexual assault patients. Although protocols differ by community, an understanding of the key concepts outlined by the San Diego County model will lead to appropriate medical interventions that preserve the ability to collect forensic evidence while concurrently protecting patients. The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has increased the frequency of intimate partner violence (IPV) and affected the availability of in-person counseling resources, increasing the need for updated guidelines (5). Health care providers must modify assessment and examination procedures during COVID-19 to protect themselves, investigators, and patients.

Definitions

According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), the country's largest anti-sexual violence organization, definitions of sexual assault, rape, and other terminology related to sexual violence and sex crimes vary by state (6). For the purposes of this article, sexual assault will refer to any form of sexual violence in which there was an unwanted attempted or completed interaction that was sexual in nature. This includes rape, sodomy, forcible penetration, sexual battery, and other similar types of incidents.

When speaking about the patient involved in a sexual assault incident, it is important to use clear terminology. Depending on the context of the discussion, the words used to refer to the affected person may change. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) providers and emergency department staff may refer to the individual as a “patient.” Law enforcement officials may refer to the person as a “victim.” In a court of law, the person may be called the “plaintiff.” That same person may also be referred to as a “survivor,” when being discussed within the realm of advocacy. Each term has nuances and connotations. For clarity and consistency, and coming from a medical perspective, this paper will refer to these individuals as “patients.”

The proper preservation and collection of forensic evidence is of paramount importance to the patient to support future legal proceedings. Forensic evidence is defined as anything that could potentially be used in a court of law. Traditional forensic evidence includes clothing, bed sheets, debris, foreign fibers, or any other material item that has come into contact with the patient and could help corroborate the history (3,7). More recent forms of forensic evidence include samples of blood or fluid collected during a forensic examination and photos taken by investigators. Regardless of the source or quantity, health care providers must respect the “chain of evidence” and be cognizant of disturbing potential evidence on initial patient contact before examination by a forensic team.

Background

San Diego Sexual Assault Response Team Program

In 1990, San Diego County implemented a Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) responsible for interdisciplinary work with sexual assault patients. When SART is activated, the program brings together a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) nurse, a law-enforcement officer, and a patient advocate. The SANE nurse is charged with forensic evidence collection and medical care; the officer pursues the criminal investigation; and the patient advocate provides support and resources for the patient. Each team member follows relevant best-practice and national guidelines, in addition to undergoing extensive and ongoing training. Although each team member has specific tasks, the overall goal of providing streamlined, trauma-informed care for the patient is the same. As of December 2019, the San Diego SART program has assisted thousands of sexual assault patients (1).

Guideline Development

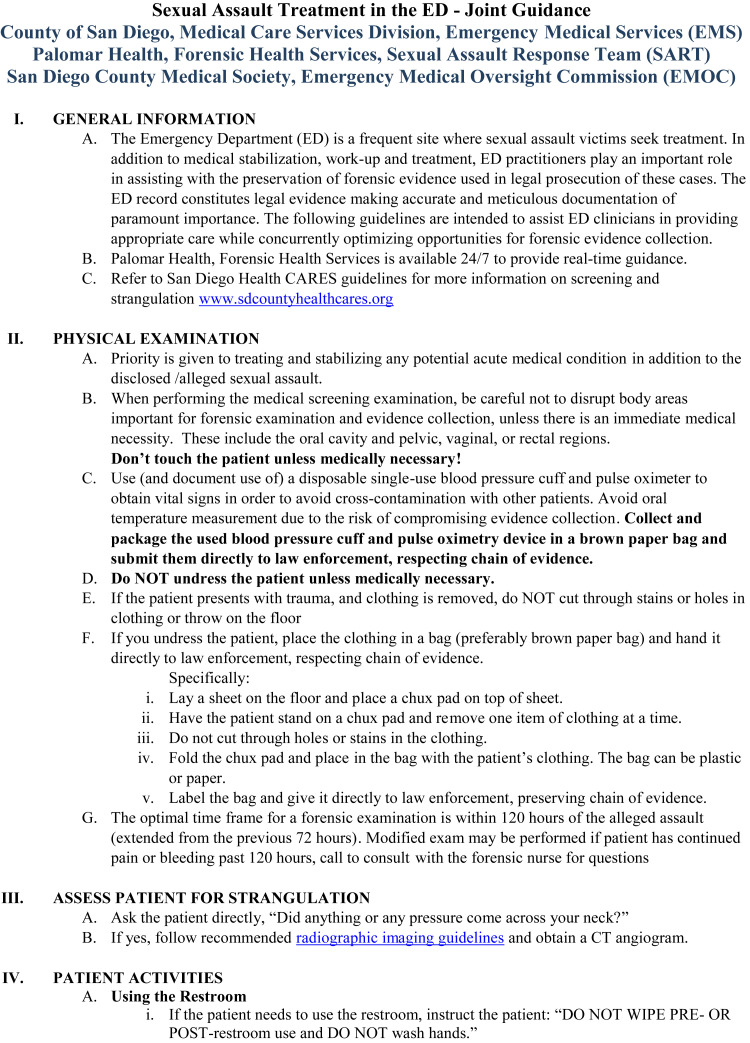

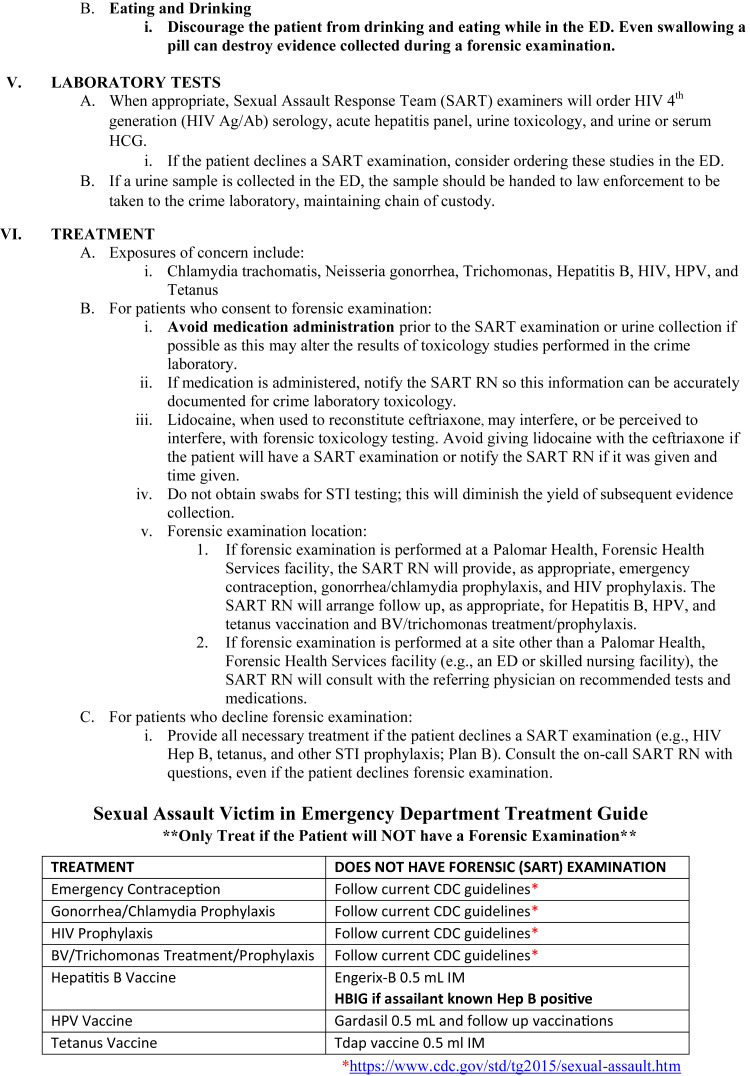

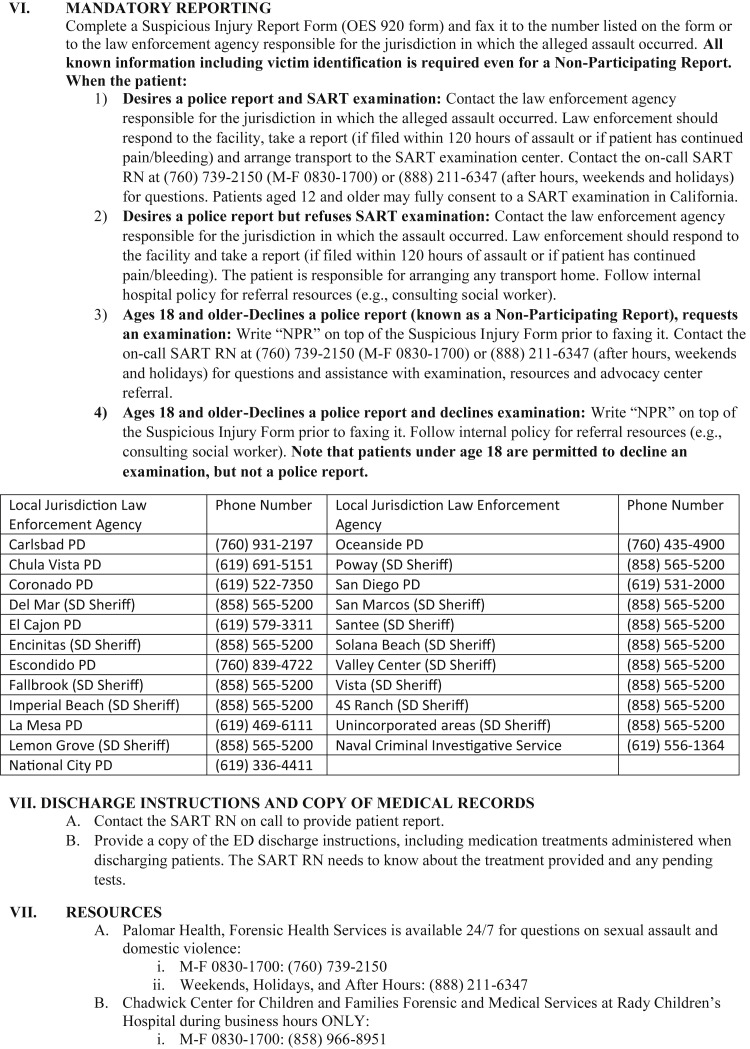

After determining a need for standardized sexual assault guidelines, experts in San Diego County drafted evidence-based, trauma-informed guidelines for frontline emergency practitioners (Figure 1 ). The County of San Diego County Emergency Medical Oversight Commission used an iterative process involving law enforcement, forensic evidence technicians, and health care professionals to develop consensus guidelines that were ultimately presented to the San Diego County Medical Society Executive Committee for endorsement. Input was collected from various groups, such as RAINN and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as from different medical specialties. After this endorsement, the model guidelines were shared with all 21 county emergency department directors for distribution to emergency clinicians.

Figure 1.

Model sexual assault guidelines from San Diego County, CA. The included San Diego County patient management guidelines were originally distributed in September 2019. BV = bacterial vaginosis; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CT = computed tomography; HBIG = hepatitis B immune globulin; HCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; Hep B = hepatitis B; HIV Ag/Ab = human immunodeficiency virus antigen/antibody; HPV = human papillomavirus; RN = registered nurse; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

SAFET-I Components

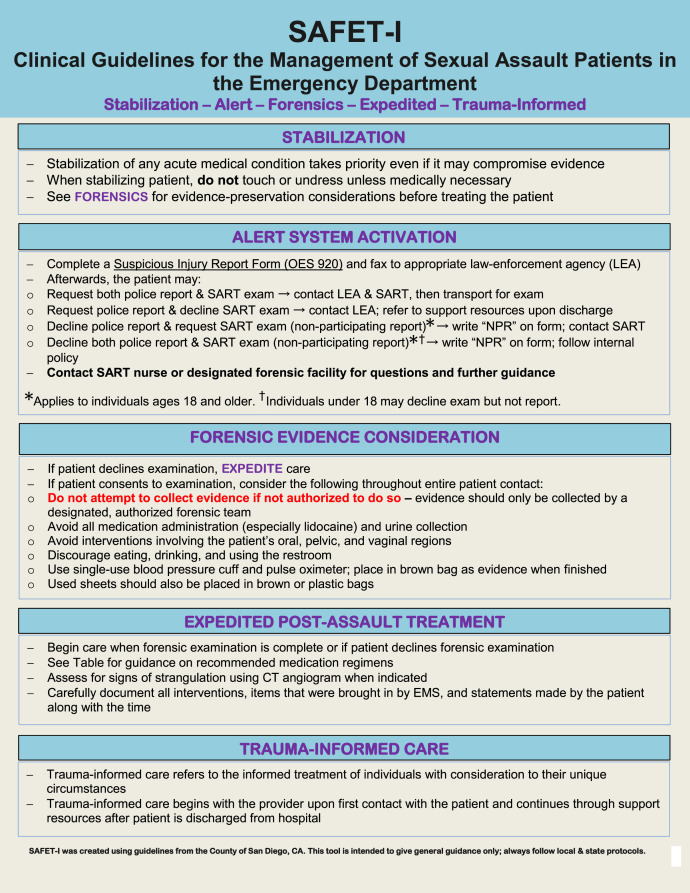

There are five components of the SAFET-I system: stabilization, alert system activation, forensic evidence consideration, expedited post-assault treatment, and trauma-informed care (Figure 2 ). SAFET-I is organized both temporally and by treatment priority.

Figure 2.

SAFET-I: Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Sexual Assault Patients in the Emergency Department. The SAFET-I framework is based on the San Diego County guidelines and consists of five main components: stabilization, alert system activation, forensic evidence consideration, expedited post-assault treatment, and trauma-informed care. CT = computed tomography, EMS = Emergency Medical Services, SART = Sexual Assault Response Team.

SAFET-I: Stabilization

Prehospital care

Some patients self-present to the ED and others are transported by ambulance. In the prehospital setting, EMS providers have the first opportunity to help sexual assault patients and are the first health care providers to contribute to the patient's medical record. During medical stabilization, EMTs and paramedics should minimize their contact with the patient to reduce the risk of compromising forensic evidence. However, evidence collection is always secondary to time-sensitive patient care—providers should not delay or withhold life-sustaining medical assessments and treatments in an effort to avoid contaminating forensic evidence.

ED care

To preserve forensic evidence, unless medically necessary (such as for management of potentially life-threatening injuries), health care providers should refrain from touching the patient until a decision can be made regarding the patient's willingness to be examined and file a police report. Once the patient has decided, the proper authorities, including the appropriate law enforcement agency and SART or equivalent, should be alerted immediately. The law enforcement agency is typically the one located in the jurisdiction where the alleged assault occurred; however, it is important to be aware of special circumstances, for example, if the patient is on active military duty.

SAFET-I: Alert System Activation

Mandated reporting

In certain US states, ED personnel are mandated reporters of sexual assault and IPV (7). Although the patient might choose not to speak with police, law enforcement must still be contacted. If an interpreter is needed, it is best to use a professional. A friend or family member of the patient could unintentionally or intentionally bias or mistranslate the information being presented.

A patient can request a medical forensic examination without a concomitant legal investigation (7). If the patient chooses to have a sexual assault forensic examination (sometimes referred to as a SAFE examination) or a sexual assault evidence kit, a forensic specialist will perform the examination. If the patient does not want to press charges, the kit can be collected anonymously regardless of the patient's choice to participate with law enforcement. This allows the patient to be evaluated for possible sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and the evidence will remain stored in case the patient wishes to involve law enforcement in the future.

Each state has different qualification requirements for specialized health care workers performing SAFE examinations. This provider might have the title of registered SANE, sexual assault forensic examiner (SAFE), Sexual Assault Forensic Medical Examiner (SAMFE) for the military, or sexual assault examiner (SAE) (7,8).

In over 70% of US emergency medicine residency programs, trainees had either no specific requirements regarding the SAFE, or only had to observe one SAFE during residency (9). This might not satisfy the American Board of Emergency Medicine's Model of Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine, which states that competency regarding assessment and examination of sexual assault patients is required (10).

SAFET-I: Forensic Evidence Consideration

Prehospital care

Health care providers should not attempt to collect forensic evidence unless specially trained and authorized to do so. If a patient's clothes must be removed in the prehospital setting to evaluate or treat traumatic injuries, care should be taken to avoid cutting through any holes or rips caused during the incident. Removed clothing should be placed into a paper bag. The sheet on the EMS gurney should also be preserved in a paper bag, as it can retain fibers or foreign materials that were on the patient. In addition, any ropes, cords, ligatures or other material tied around the patient's neck or body should be carefully removed in a way that preserves the knot for later forensic examination (11).

ED

On arrival to the ED, all collected evidence should be handed off and documented in the patient's chart. There should not be any gaps in the documentation as to when the evidence was collected and who handled it. Any gaps in the chain of evidence might introduce confounding factors that could result in evidence being disregarded in court. Standardized collection of forensic evidence will better serve the patient in future prosecution (12,13).

A SAFE examination can take several hours and includes a history and thorough physical examination. The patient might opt out of any portion of the examination, for any reason (7,8). The US Federal Violence Against Women Act, initially passed in 1994, ensures that sexual assault patients are not financially responsible for forensic examinations (i.e., “rape kits”) or PEP. If patients are unsure whether they want to pursue legal action against the perpetrator, the kit can be collected anonymously. This allows gathering of evidence without the patient having to make an on-the-spot decision about whether to pursue legal action (13).

Policies that address the management of an incapacitated or unconscious sexual assault patient are essential. Collection of forensic evidence can be time-sensitive; however, the sexual assault forensic examination is invasive and extensive, so ideally the patient must be able to consent (14).

Patient activities

Even if they have no apparent traumatic injuries, it is important that patients refrain from certain activities, such as drinking, bathing, using the restroom, hair brushing, or any other activity that could disrupt or damage the evidence before their examination. Water or any other drinks can wash away evidence that would have otherwise been detected by a swab. Every time the patient voids, evidence can be wiped away or become contaminated (2,3,8). Withholding water or not allowing a traumatized patient to shower can seem cruel and diminish the patient's ED experience. Health care providers should explain to the patient that certain activities are temporarily prohibited to preserve evidentiary integrity. This also illustrates why sexual assault patients should be considered priority patients.

Suspect examinations

If a suspect is taken into custody and needs a forensic examination or medical treatment, the individual should not be treated in the same facility as the victim. Although in the custody of law enforcement, a statement will be taken from the suspect and a forensic examination initiated by SART. Law enforcement will be present to observe a suspect examination in contrast to the patient's examination. Even if there is little or no information from law enforcement regarding the suspect's status, it is crucial that providers practice trauma-informed care by carefully considering how emerging information could negatively affect the patient's mental state.

Certain factors related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic must be considered, including use of appropriate personal protection equipment (PPE). The physical location of the examination must be within a space large enough to accommodate social distancing among the law enforcement officer, provider, and suspect. Due to the need to protect evidence from contamination, PPE worn by forensic providers is generally sufficient to protect against virus transmission when examining a patient who may infected with COVID-19; however, additional precautions must still be taken.

SAFET-I: Expedited Post-Assault Treatment

Assessment for patient strangulation

The patient should be asked, “Did anything or any pressure come across you neck?” The patient might not show any outward signs of neck trauma. Even with no physical signs, if the patient affirms the history, a computed tomography angiogram of the neck should be obtained. Life-threatening injuries have been detected in patients with minimal or no signs of external trauma (15).

Laboratory tests and treatment

Guidelines published by CDC in 2017 describe appropriate nonoccupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) treatment for victims of sexual assault (Table 1 ). Sexual assault patients are at risk for contracting Chlamydia trachomat is, Neisseria gonorrhea, Trichomonas spp., Clostridium tetani, hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human papillomavirus (HPV). CDC guidelines outline specific factors that may impact nPEP recommendations (16).

Table 1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Recommendations

| Medication | Dose | Route | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone plus | 250 mg | i.m. | Once |

| Azithromycin plus | 1g | p.o. | Once |

| Metronidazole or | 2 g | p.o. | Once |

| Tinidazole | 2 g | p.o. | Once |

i.m. = intramuscular; p.o. = per os.

Some experts have expressed concern that reconstituting ceftriaxone with lidocaine could cause a false-positive cocaine toxicology screen, given that both cocaine and lidocaine are “-caine” drugs (17). A false-positive screen could imply the patient had been using drugs, which could bias legal proceedings. However, research has shown that a false-positive toxicology screen is unlikely to occur, as lidocaine is an amide anesthetic and cocaine is an ester anesthetic, resulting in structurally distinct chemical compositions (18).

On arrival to the ED, some patients might be intoxicated with alcohol. To prevent a disulfiram-like drug reaction, it is recommended that the patient be given a prescription for metronidazole or tinidazole to take at home with precautions against concurrent drinking, rather than being administered these medications in the ED.

To determine whether HBV PEP is indicated, a patient's HBV immunization status must first be determined. For an unvaccinated patient in a case in which the alleged perpetrator is known to be HBV-positive, start the HBV vaccine series, and administer hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG). Ideally, this should be completed within 24 hours of exposure. The patient will need additional doses of the HBV vaccine at 1 and 6 months. If the patient is unvaccinated and the perpetrator is of unknown status, the patient should receive the first dose of the HBV vaccine series in the ED, and the subsequent doses as an outpatient. Finally, if the patient has documented vaccination and immunity, then neither the HB vaccine nor HBIG are indicated.

For the HPV prophylaxis, recommendations as of 2020 are that the HPV vaccine should be given to female patients aged 9 to 26 years old and male patients aged 9 to 21 years old if they have not been vaccinated previously. If the patient is a male and has had sex with other men, the HPV vaccine is recommended up through age 26 years.

Initially, HPV vaccination was a series of 3 injections for all patients. If a patient is between 9 and 14 years old when starting the vaccine, a newer recommendation is to give 2 doses of the vaccine. Patients who are immunocompromised or between 15 and 26 years old when starting the HPV vaccine series should receive 3 doses. For EDs that do not have access to the HPV vaccine, it is recommended that patients be advised to obtain the vaccine as an outpatient as soon as possible. PEP for HIV is most effective when initiated as soon as possible—preferably within 72 hours after the incident (Table 2 ) (19).

Table 2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Human Immunodeficiency Virus Post-Exposure Prophylaxis∗

| Medication | Dose | Route | Frequency | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus | 300 mg | p.o. | Once daily | 28 days |

| Emtricitabine plus | 200 mg | p.o. | Once daily | 28 days |

| Raltegravir or | 400 mg | p.o. | Twice daily | 28 days |

| Dolutegravir | 50 mg | p.o. | Once daily | 28 days |

p.o. = per os. ∗Preferred 28-day regimen for individuals ≥13 years, inclduing pregnant women, with creatinine clearance ≥60 mL/min. See full CDC guidelines for treatment variations.

Per CDC guidelines, confirmed and probable cases of chlamydia, chancroid, gonorrhea, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and syphilis are reportable to the state health department (20). Part of PEP also includes prevention of unwanted pregnancy through emergency contraception. After obtaining a pregnancy test, there are several potential options. Ulipristal, which has shown the highest oral efficacy when used within 120 hours of the incident, is given as a one-time 30 mg oral dose. The most effective form of emergency contraception is insertion of a copper intrauterine device, but this might not be readily available in the ED. In addition, placement can be uncomfortable for a patient who has just experienced a sexual assault. A third option is to give a single oral dose of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg, which can be used up to 72 hours after the incident. Other PEP includes offering tetanus vaccine if indicated based on the specific injuries found on examination (12).

Pregnant women

In addition to their medical and trauma care and subsequent SAFE examination, pregnant patients might need additional prenatal monitoring in labor and delivery. The same post-assault testing is recommended as for nonpregnant patients, including HIV, syphilis, and HBV serologies. The HIV PEP medications, which are pregnancy category B and C, are appropriate for pregnant women (Table 2) (12).

SAFET-I: Trauma-Informed Care

Emotional support

Sexual assault can have a lasting impact on emotional and psychological well being. A patient-centered, trauma-informed approach to care helps mitigate the psychological and emotional impact of the event (8,14). The practice of trauma-informed care has been developed as a way to approach traumatic events, including sexual assault, from a behavioral health standpoint. Trauma-informed care encompasses key principles, such as encouraging safety and empowerment of the patient, providing transparency and peer support, collaborating with other agencies (such as law enforcement), and being sensitive to a patient's culture and gender (21). In addition to supporting the patient, parents and other caregivers will also need emotional support and resources. The impact that these cases may have on health care providers should not be overlooked, and support should also be available to prehospital personnel and ED staff.

In the aftermath of a sexual assault, a distressed and traumatized patient can display a range of emotional reactions, from anger to denial to complete dismissal of the event. The patient might be hesitant to speak about the incident or to agree to an examination. Each reaction is valid and does not indicate whether a sexual assault occurred. Providing a consistent message of support, such as by telling patients that the event was not their fault, is helpful.

Special victim considerations

Some sexual assault patients are children or adolescents, developmentally delayed adults, or elderly patients with dementia. These are examples of special populations who might not have the capacity to understand what has occurred. Maintaining a high level of suspicion when there is an unclear story or unexplained injuries, pregnancy, or STIs can help a provider uncover that a sexual assault has occurred. If available, these patients would benefit from being evaluated by a SANE/SAE with special training in pediatrics or other relevant populations (14).

Pediatric patients might benefit from age-appropriate explanations as to why they need an examination in the ED. It is important to tell patients that they are not in trouble, and that the event was not their fault. However, it is prudent to minimize the number of times the child is interrogated after an initial disclosure. Providers in the ED should not ask any questions that could appear to be leading. The local Child Advocacy Center should be contacted and an interview conducted by a specially trained forensic interviewer. A specialized forensic examination will also be performed and STI tests initiated for prepubescent children.

In every US state, it is permissible to treat adolescents for STIs without parental consent. It is important to provide counseling about safe sex practices and verify whether sexual activity was consensual. If a prepubescent child is found to have an infection such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis, there should be a strong suspicion of sexual assault and the incident must be investigated further (12).

For patients suspected to have experienced sexual assault, maintain a high level of suspicion for sex trafficking. Certain red flags should trigger additional investigation by appropriate authorities, such as law enforcement, social workers, or child protective services (CPS). These red flags include multiple visits with similar symptoms; recurrent STIs or unwanted pregnancies; being dressed inappropriately for the weather; an inconsistent history or unexplained injuries; being accompanied by someone who does not allow the patient to speak for themselves and will not leave the patient's side; patients not being in possession of their own documents or knowing their addresses or whereabouts; or if they display behavior that seems overtly fearful, hostile, or detached (22). On examination, the patient might have tattoos that are related to currency, such as dollar signs, money bags, a diamond, a bar code, or the phrases “for sale,” or “Property of…” (23). When a patient is suspected to be a victim of sex trafficking, the National Human Trafficking Resource Center is available at 1-888-373-7888 to provide assistance. Their 24-hour support center includes resources about local shelters, law enforcement, and other social support services (22).

Discussion

There is a lack of literature directed toward EMS and ED health care providers regarding sexual assault patient management and evidence-preservation guidance. On first patient contact, whether in the prehospital setting or the ED, the goals of medical stabilization and treatment versus evidence collection for later prosecution might conflict with one another. In addition, health care providers must not only consider their own well being, but what is most medically and psychologically necessary for the patient at the time, even if it means potentially compromising forensic evidence. Although the guidelines presented in this article apply to practice before COVID-19, there are several special considerations that would not be present before the pandemic. These include the increased concern about IPV with stay-at-home orders and general situational stress (e.g., uncertainty, loss of income, food insecurity), as well as more practical issues like PPE and physical distancing requirements. Implementation of SAFET-I guidelines should be made with consideration to events caused by COVID-19 and existing services for sexual assault patients.

Special Considerations for COVID-19

As of April 2020, many countries have implemented shelter-in-place mandates and have temporarily banned all nonessential outside activities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although these policies have proven beneficial in slowing the spread of the virus, they have also unintentionally exposed vulnerable individuals to a greater risk of IPV by limiting their movement and contact with others. In addition, other psychological factors, including elevated stress from losing one's job and loss of financial security, are likely to exacerbate these conditions (24).

Early reports indicate higher levels in IPV across many countries, including the United States, France, and South Africa, that parallel the implementation of stay-at-home orders (25). Data are evolving regarding what forms of IPV are increasing and in what proportion of cases sexual assault is a component. In the era of COVID-19, it is critical for health care providers to screen for signs of suspected IPV and to treat sexual assault victims as priority patients.

Many hospitals are observing historically low numbers of non-COVID patients, including myocardial infarction and stroke cases. In addition, individuals might avoid accessing health care services out of fear of contracting COVID. Health care providers can represent the first and last point of support for IPV victims and sexual assault patients who cannot seek help elsewhere for any reason. Therefore, during the ongoing pandemic, health care providers have a greater responsibility to advocate for sexual assault and IPV patients. Providers should familiarize themselves with local current events and the availability of resources to better support patients during times of increased external stressors, such as is the case during a global pandemic.

Implementation Considerations

San Diego County distributed its model consensus guidelines in September 2019 (Figure 1). Before implementing guidelines, knowledge of available local programs and how to activate them is of paramount importance to prehospital and ED providers. In general, SART partners should also follow their own agency guidelines but may defer to SAFE program requirements if a higher level of protection is needed. Guidelines should also be used in conjunction with up-to-date information from CDC.

In the event of system-wide disruptions, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, health care providers should be made aware of any operational changes to SAFE examinations. Patients seeking treatment, and the community at large, should be informed that the health care system is still able to provide medical forensic examinations. In addition, providers should offer guidance regarding the measures used to keep patients safe and the steps to obtain an examination (26).

Limitations

Specific guidelines involving each component of SAFET-I can differ at the facility, local, state, and national levels. Variable cultural norms in different countries might also necessitate adaptation of the tool for local customs. In addition, legal frameworks vary by locality. The best-practice guidelines contained within this article are recommendations and do not constitute legal advice.

Conclusions

The SAFET-I Tool and model San Diego County ED consensus guidelines provide a standardized approach for trauma-informed management of the sexual assault patient, beginning from first patient contact until discharge. The model presented also accounts for special circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. An understanding and application of the evidence-based, trauma-informed principles summarized in the SAFET-I tool will benefit ED clinicians in the management of sexual assault patients, lessening the psychological impact on the patient and increasing opportunities for successful prosecution.

References

- 1.Straight J.D., Heaton P.C. Emergency department care for victims of sexual offense. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1845–1850. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton M. The forensic aspects of sexual violence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexual Assault and Abuse and STDs—2015 STD Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/sexual-assault.htm Available at:

- 4.San Diego County District Attorney. San Diego County Health—CARES. www.sdcountyhealthcares.org Available at:

- 5.Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) What is a sexual assault forensic exam? https://www.rainn.org/articles/rape-kit Available at:

- 7.Riviello R.J., Rozzi H.V. Know the legal requirements when caring for sexual assault victims. ACEP Now. 2018;37(11) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingemann-Hansen O., Charles A.V. Forensic medical examination of adolescent and adult victims of sexual violence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sande M.K., Broderick K.B., Moreira M.E. Sexual assault training in emergency medicine residencies: a survey of program directors. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14:461–466. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.2.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Physician’s Weekly Sexual assault training for ED residents. https://www.physiciansweekly.com/sexual-assault-training-emergency-department/ Available at:

- 11.Linden J.A. Care of the adult patient after sexual assault. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:834–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1102869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Justice A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations: Second Edition. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ovw/241903.pdf Available at:

- 13.H.R.1585 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1585/text Available at:

- 14.Association of Child Life Professionals Sexual assault examinations in a pediatric emergency setting. https://www.childlife.org/membership/aclp-bulletin/fall-2018-table-of-contents/sexual-assault-examinations-in-a-pediatric-emergency-setting Available at:

- 15.Family Justice Center Recommendations for the medical/radiographic evaluation of acute adult, non-fatal strangulation. https://www.familyjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Recommendations-for-Medical-Radiological-Eval-of-Non-Fatal-Strangulation-v4.9.19.pdf Available at:

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/sexual-assault.htm Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.White R.M., Eisenhart P.F. Drug testing and ‘caine’ drugs. Chem Eng News. 2009;87(47):4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim E., Murray B.P., Salehi M. Does lidocaine cause false positive results on cocaine urine drug screen? J Med Toxicol. 2019;15:255. doi: 10.1007/s13181-019-00720-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and US Department of Health and Human Services, Updated Guidelines for Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV–United States, 2016. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/programresources/cdc-hiv-npep-guidelines.pdf Available at:

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National notifiable conditions. 2019. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/notifiable/2019/ Available at:

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf Available at:

- 22.National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) What to look for in a healthcare setting. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/resources/what-look-healthcare-setting Available at:

- 23.Fang S., Coverdale J., Nguyen P. Tattoo recognition in screening for victims of human trafficking. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206:824–827. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Domestic Violence Hotline Staying Safe During COVID-19. https://www.thehotline.org/2020/03/13/staying-safe-during-covid-19/ Available at:

- 25.United Nations News UN Chief calls for domestic violence ‘ceasefire’ amid ‘horrifying global surge. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061052 Available at:

- 26.Cal-SAFE COVID-19 guidance. http://www.calsafe.net/covid-19-guidance.html Available at: