Abstract

Background:

In high HIV burden settings, maximizing the coverage of prevention strategies is critical to achieving epidemic control. However, little is known about the reach and impact of these in some communities.

Methods:

We undertook a cross sectional community survey in the adjacent Greater Edendale and Vulindlela areas in the uMgungundlovu district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Using a multistage cluster sampling method, we randomly selected enumeration areas, households and individuals. One household member (15–49 years) selected at random was invited for survey participation. Following consent questionnaires were administered to obtain socio-demographic, psycho-social, behavioural information and exposure to HIV prevention and treatment programmes. Clinical samples were collected for laboratory measurements. Statistical analyses were performed accounting for multilevel sampling and weighted to represent the population. Multivariable logistic regression model assessed factors associated with HIV infection.

Findings:

Between June 11, 2014 to June 22, 2015, we enrolled 9812 individuals. The population-weighted HIV prevalence was 36·3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 34·8–37·8, 3969 of 9812); 44·1% (42·3–45·9, 2955 of 6265) in women and 28·0% (25·9–30·1, 1014 of 3547) in men (p<0·0001). HIV prevalence in women 15–24 years was 22·3% (20·2–24·4, 567 of 2955) compared to 7·6% (6·0–9·3, 124 of 1024) (p<0·0001) in men of the same age. Prevalence peaked at 66·4% (61·7–71·2, 517 of 760) in women 35–39 years and 59·6% (53·0–66·3, 183 of 320) in men 40–44 years. Consistent condom use in the last 12 months was 26·5% (24·1–28·8, 593 of 2356) in men and 22·7% (20·9–24·4, 994 of 4350) in women, (p=0·0033); 35·7% (33·4–37·9, 1695 of 5447) of women’s male partner and 31·9% (29·5–34·3, 1102 of 3547) of men were medically circumcised (MMC), (p<0·0001), whilst 45·6% (42·9–48·2, 1251 of 2955) of women and 36·7% (32·3–41·2, 341 of 1014) of men reported antiretroviral therapy (ART) use (p=0·0003). HIV viral suppression was achieved in 54·8% (52·0–57·5, 1574 of 2955) of women and 41·9% (37·1–46·7, 401 of 1014) of men (p<0·0001) and 87·2% (84·6–89·8, 1086 of 1251) of women and 83·9% (78·5–89·3, 284 of 341) (p=0·3670) men on ART. Age, incomplete secondary schooling, being single, having more than one lifetime sex partners (women), sexually transmitted infections and not being medically circumcised were associated with HIV positive status.

Interpretation:

The HIV burden in specific age groups, the suboptimal differential coverage, and uptake of HIV prevention strategies justifies a location-based approach to surveillance with finer disaggregation by age and sex. Intensified and customised approaches to seek, identify, and link individuals to HIV services are crucial to achieving epidemic control in this community.

Keywords: Surveillance, Community HIV prevalence, CD4 cell counts, HIV viral load, HIV prevention strategies, antiretroviral therapy (ART), KwaZulu-Nata

Background

South Africa contributes about 18% of the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) burden.1 In 2016, an estimated 7·1 million South Africans were living with HIV, 270 000 new HIV infections and 110 000 acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related deaths occurred, whilst over 3·9 million adults (age 15+ years) living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART).1 National and regional HIV prevalence surveys feed into the country’s information base and help monitor epidemic trends over time.2, 3 In 2002, HIV prevalence among South Africans was 11·4% and by 2012 increased to 12·6%, whilst prevalence among 15–49-year olds increased from 15·6% to 18·8% over the same period. Provincially, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) had the highest prevalence which increased from 15·7% in 2002 to 27·9% in 2012 compared to the Western Cape which showed a decline from 13·2% in 2002 to 7·8% in 2012.2

In response to the ongoing high HIV prevalence, the South African government, in 2010, launched a national campaign to increase4 access to HIV testing services (HTS) to enhance knowledge of HIV status and uptake of ART,5 prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV,6 medical male circumcision (MMC),7 provision of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and recently expanded the provision of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).8 To fast-track the response to HIV and AIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets9,10 and the universal test and treat11 strategy have been adopted. These collectively aimed at reducing HIV transmission potential to reduce new infections, AIDS related morbidity and mortality and increase life expectancy12–14 It is imperative that as programmes are scaled-up, HIV surveillance is similarly critical to provide comprehensive structural, behavioural and biological data to determine barriers and facilitators of programmatic impact on underlying dynamics of transmission within communities and geographical areas.1,15 These are fundamental to achieve the optimistic and sustainable goals towards HIV epidemic control;16 which is ending the AIDS epidemic by the year 20301 with the realisation of an AIDS-free generation.17

The HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System (HIPSS) has been established as a surveillance platform in a geographically defined region in KZN, South Africa to assess the impact of HIV prevention efforts in a “real world”, non-trial setting.18 We report on the baseline findings of gender and age specific HIV prevalence, sociodemographic, biological and behavioural factors associated with HIV and the contemporaneous coverage of HIV prevention strategies.

Methods

Survey setting and source population

The household survey was undertaken in rural Vulindlela and the adjacent peri-urban Greater Edendale area in the uMgungundlovu district of KZN, South Africa.18 Vulindlela has just over 150 000 people, is mainly rural and has limited employment opportunities through the commercial forestry projects and the neighbouring residential and manufacturing towns. The Greater Edendale area has a population of just over 210 000 people and consists of informal settlements, townships and peri-urban areas. Primary health care clinics and community-based organizations provide health care and psychosocial support, whilst district partners including the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) provide technical support to strengthen health services. Partnerships with stakeholders including health-service providers and traditional leaders from the community contribute to the development of research programmes in the area recognising the high HIV burden in the district.2,3

Survey design and procedures

We used multistage cluster sampling to randomly select 221 of the 591 enumeration areas followed by random selection of 50 households in each enumeration area. Households were located on maps and study staff approached the head or designate, provided study information, obtained verbal consent, confirmed the selected household with the Global Positioning System (GPS) co-ordinates, administered the general household questionnaire and enumerated household members. Since the potential to overestimate HIV prevalence through clustering of infections within households, only one household member (15–49 years) was selected at random and invited for survey participation. For participants agreeing to provide clinical samples and participate in the study, we obtained written informed consent for those 18 years and older, assent with parental consent for those <18 years in English or isiZulu followed by obtaining fingerprints using a mobile biometric scanner.

Questionnaires were programmed on handheld personal digital assistants (PDAs) by MobenziR Researcher (Durban, South Africa) and administered by study staff to obtain general socio-demographic, psychosocial and behavioural information. Information on HIV prevention and treatment exposures was obtained. This included access to and use of condoms, access to HTS, frequency of testing for HIV, knowledge of HIV status, self-reported ART use and male circumcision status ascertained with the aid of a chart with visual representation of traditional or medical circumcision and whether the procedure was carried out by professional health care personnel within health care facilities or as part of socio-cultural practices of rituals of passage into manhood undertaken in non-clinical settings by non-professional members. Clinical samples collected were peripheral blood, urine (men) and self-collected vulvo-vaginal swabs (women). Participants were assigned a unique study number that linked them to the household, samples and fingerprints. We tested samples for HIV antibodies using the 4th generation HIV enzyme Biomerieux Vironostika Uniform II Antigen / Antibody Microelisa system (BioMérieux, Marcy I’Etoile, France) and confirmed positive samples with the HIV 1/2 Combi Roche Elecys (Germany) (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) and HIV-1 Western Blot Biorad assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Redmond, WA, USA). All indeterminate results were resolved using ADVIA Centaur® HIV Antigen/Antibody Combo (CHIV) Assay (Siemens, Tarry Town, USA). We measured CD4 cell counts using Becton Dickinson (BD) FACS Calibur flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) and HIV viral load using the Roche COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 v2.0 assay (CAP /CTM HIV-1 V2.0). (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) with a dynamic range of 20 to 10 million copies/ml. Participants were provided with barcoded referral cards and advised to return to their health clinic to access results and follow-up care.

Regulatory Approvals

The protocol, informed consent and data collection forms were reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, (Reference number BF269/13), KZN Provincial Department of Health (HRKM 08/14) and the Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States of America.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). SAS SURVEY procedures which accounted for the multi-level sampling and study weights were used. Sampling weights were calculated taking into account the probabilities of selecting the enumeration area, the household in the enumeration area and the individual in the household, weighted for non-response and rescaled to the size of the population in the survey area using the StatsSA 2011 Census population19. Descriptive statistics using unweighted counts and population-weighted percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented. Taylor series linearization methods were used to estimate standard errors of estimates, from which Wald confidence limits were derived. A design-adjusted Chi-squared test was used to test for the association between sociodemographic, behavioural and biological factors and HIV prevalence. To identify factors associated with HIV infection we assessed individual-level predictors in a multivariable logistic regression model that corrected for sampling and non-response biases and used the Taylor series linearization method for estimation of standard errors. Missing values of a predictor were included as a separate category of the predictor as all predictors were categorical variables. To calculate the median and geometric mean viral load, samples with undetectable or <20 copies per mL of viral load were assigned a value of one (1) or ten (10) copies per mL respectively and reported as <20 copies per mL for the lower limit. We defined viral suppression as viral load <400 copies per mL

Role of the funding source

The funders of the survey contributed to the survey design and study monitoring; contribution, review and approval of publications. ABMK, LL and AG had full access to all the data. ABMK, CC and DK had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between June 11, 2014 to June 22, 2015, 15100 households were approached, 14618 were occupied, 11289 head or designate consented to household participation and 9812 individuals were enrolled. Overall, 14.7% of households and 5.1% of individuals refused participation, accounting for 69.1% of individuals from the occupied households participating and 86.7% participating from the enrolled households (Appendix 1).

Of the household members enumerated, 22369 (58.2%) were females and 16072 (41.8%) were males (Appendix 2). The average household size was 3·6 members (range 1–20). The median age of household members overall was 26·1 years [interquartile range (IQR) 13·4–45·4] for females and 20·7 years (10·1–35·4) for males. A total of 24701 (64·3%) of the household members were of working age (15–64 years). About a third (36·0%) had incomplete secondary schooling, a third (34·0%) were unemployed and a third (36·9%) of household members were financially reliant on social support grants. Overall, 98·6% of households were connected to electricity, 94·4% had access to piped water and 25·5% had their toilet connected to a public sewer system.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants. The median age of women was 27·4 years (IQR 20·6–36·2) and men was 26·4 years (20·1–35·0). Based on self-reported data, 41·3% of women and 38·1% men had completed secondary schooling. Excluding non-responses, for more than 90% of participants the total monthly household income was R6000 or less. Only 9·7% of women and 11·2% of men had been away from home for more than a month in the last year, yet 88.7% of men and 81.4% of women were single and not living with their partner. The median age at first sex for women and men was 17·5 years (16·1–19·1) and 16·5 years (15·1–17·9) respectively (p<0·0001); the median age of the first sex partner for women was 20·4 years (18·5–23·0) and for men it was 16·1 years (14·8–17·6), p<0·0001. Women had fewer lifetime sex partners [median 2 (1–3)], compared to men [median 3 (1–6)], p<0·0001.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of men and women (n=9812) in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015

| Women (n=6265) |

Men (n=3547) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 27·4 (20·6–36·2) | 26·4 (20·1–35·0) | ||

| Age group in years | ||||

| 15–19 | 958 | 18·2% | 658 | 19·6% |

| 20–24 | 1266 | 19·5% | 814 | 20·8% |

| 25–29 | 1087 | 17·9% | 602 | 18·2% |

| 30–34 | 833 | 13·7% | 461 | 13·9% |

| 35–39 | 760 | 12·3% | 405 | 12·3% |

| 40–44 | 660 | 9·6% | 320 | 8·6% |

| 45–49 | 701 | 8·9% | 287 | 6·5% |

| Education | ||||

| No schooling/pre-primary | 265 | 2·7% | 153 | 2·9% |

| Primary (Grade 1–7) | 375 | 5·5% | 232 | 6·5% |

| Incomplete secondary (Grade 8–11) | 2674 | 45·1% | 1547 | 47·0% |

| Completed secondary (Grade 12) | 2603 | 41·3% | 1406 | 38·1% |

| Tertiary (Diploma/degree) | 345 | 5·3% | 207 | 5·4% |

| No response | 3 | 0% | 2 | 0% |

| Total household income per month (ZAR15 = US$1) | ||||

| No income | 766 | 9·6% | 524 | 12·0% |

| ZAR 1–500 | 614 | 6·7% | 293 | 5·7% |

| ZAR 501–2 500 | 2720 | 42·7% | 1436 | 40·4% |

| ZAR 2501–6000 | 1197 | 24·2% | 705 | 24·4% |

| >ZAR 6000 | 432 | 7·5% | 242 | 6·9% |

| No Response | 536 | 7·7% | 347 | 8·7% |

| Living in community | ||||

| Always | 4890 | 77·7% | 2849 | 80·5% |

| Moved in <1 year ago | 183 | 2·5% | 71 | 1·6% |

| Moved in >1 year ago | 1180 | 19·7% | 621 | 17·8% |

| No response | 12 | 0·1% | 6 | 0·1% |

| Away from home >1 month in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 623 | 9·7% | 398 | 11·2% |

| No | 5620 | 90·1% | 3135 | 88·5% |

| No response | 22 | 0·2% | 14 | 0·2% |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single, not living with partner | 5055 | 81·4% | 3168 | 88·7% |

| Legally married | 682 | 11·7% | 180 | 5·9% |

| Single, but in stable relationship | 246 | 3·2% | 125 | 2·9% |

| Living together like husband and wife | 175 | 2·5% | 61 | 2·0% |

| Widowed | 76 | 0·8% | 6 | 0·2% |

| Divorced | 17 | 0·2% | 4 | 0·1% |

| Separated, but still legally married | 14 | 0·2% | 3 | 0·2% |

| Sexual behavioural characteristics | ||||

| Median age in years (IQR) at first sex | 17·5 (16·1–19·1) | 16·5 (15·1–17·9) | ||

| Median age in years (IQR) of partner at first sex | 20·4 (18·5–23·0) | 16·1 (14·8–17·6) | ||

| Median number (IQR) of lifetime sex partners | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–6) | ||

% = population-weighted percentage;

IQR= Interquartile range;

ZAR= South African Rand;

No response included in percentage calculation

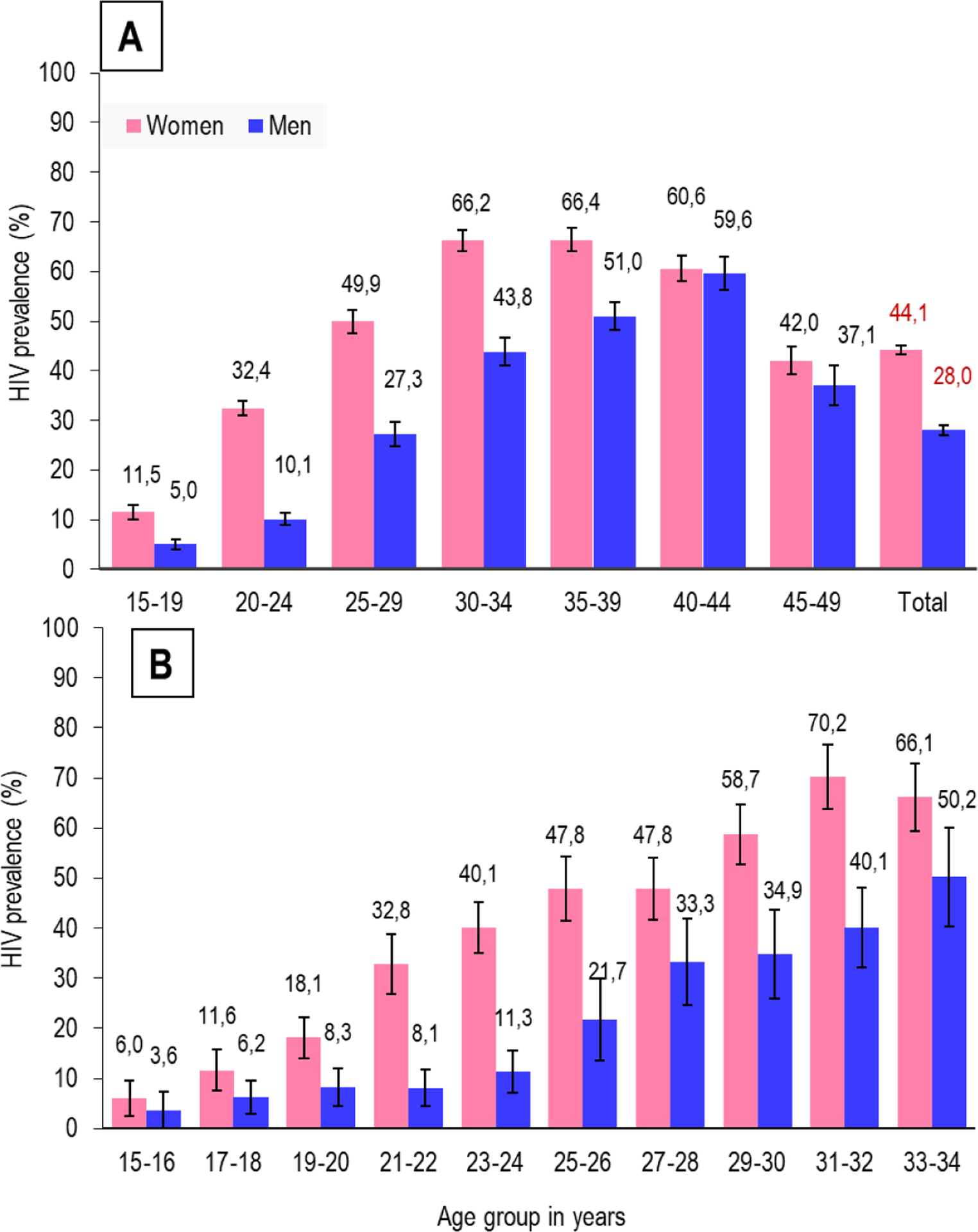

Figure 1A shows the overall population-weighted HIV prevalence of 36·3%; 44·1% in women and 28·0% in men (p<0·0001). In the age group 15–19 years, prevalence in women was 11·5% and 5·0% in men (p<0·0001), whilst among 20–24 years, HIV prevalence was threefold higher in women compared to men; 32·4% versus (vs) 10·1%, (p<0·0001). In men, HIV prevalence increased sharply from 10·1% in the age group 20–24 to 27·3% in the 25–29-year age group. Prevalence increased with age and was consistently higher in women across all age groups compared to men. Prevalence peaked at 66·4% in women in the age group 35–39 years and 59·6% in men in the age group 40–44 years. Figure 1B shows the HIV prevalence among 15–34 year olds by gender and by two-year age bands. In young women, 15–16 years-old, HIV prevalence was 6·0% and increased over 5-fold to 32·8% in the 21–22 year age group, and over 6-fold to 40·1% in the 23–24 year age group. HIV prevalence in similar age men was consistently lower than their female counterparts, however, HIV prevalence in men 15–16 years old was 3·6% and increased almost 3-fold to 8·3% in the age group 19–20 years and nearly 6-fold to 21·7% in the 25–26 year age group.

Figure 1: Population-weighted HIV sero-prevalence in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015.

(A) By gender and age (B) By gender in two-year age bands (Error bars=95% confidence interval)

Table 2 shows population-weighted HIV prevalence by sociodemographic, behavioural and biological characteristics stratified by gender. HIV prevalence was associated with age-25 years and older, incomplete education, lower household monthly income, relationship status, absence of condom-use at first sex, higher number of lifetime sex partners, ever used alcohol, history of pregnancy, and past diagnosis of tuberculosis and/or sexually transmitted infections (STI). However, being away from home and age of partner at first sex were not associated with HIV prevalence among men and women. Among men, HIV prevalence was lower in those reporting to be medically circumcised compared to those uncircumcised and traditionally circumcised, and higher among those with sexual debut ≥18 years.

Table 2:

HIV prevalence by baseline characteristics among men and women in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015

| Variable | Women (n=6265) | Men (n=3547) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | HIV prevalencea, f (95% CI) | n/N | HIV prevalencea, f (95% CI) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Overall | 2955/6265 | 44·1 | (42·3–45·9) | 1014/3547 | 28·0 | (25·9–30·1) |

| Age (years) specific | ||||||

| 15–19 | 131/958 | 11·5 | (8·6–14·4) | 36/658 | 5·0 | (3·1–70) |

| 20–24 | 436/1266 | 32·4 | (29·4–35·5) | 87/814 | 10·1 | (7·6–12·6) |

| 25–29 | 578/1087 | 49·9 | (45·2–54·5) | 171/602 | 27·3 | (22·4–32·2) |

| 30–34 | 561/833 | 66·2 | (62·0–70·4) | 215/461 | 43·8 | (38·2–49·4) |

| 35–39 | 517/760 | 66·4 | (61·7–71·2) | 209/405 | 51·0 | (45·3–56·7) |

| 40–44 | 426/660 | 60·6 | (55·5–65·7) | 183/320 | 59·6 | (53·0–66·3) |

| 45–49 | 306/701 | 42·0 | (36·5–47·6) | 113/287 | 37·1 | (29·1–45·2) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| No schooling/pre-primary | 136/265 | 46·1 | (39·2–53·0) | 49/153 | 33·0 | (24·5–41·4) |

| Primary (Grade 1–7) | 221/375 | 55·1 | (48·7–61·6) | 94/232 | 40·2 | (32·3–48·1) |

| Incomplete secondary (Grade 8–11) | 1304/2674 | 45·6 | (43·1–48·0) | 493/1547 | 30·8 | (27·1–34·5) |

| Completed secondary (Grade 12) | 1177/2603 | 42·3 | (39·7–44·8) | 348/1406 | 24·2 | (21·4–27·0) |

| Tertiary (Diploma/degree) | 116/345 | 33·4 | (26·6–40·2) | 30/207 | 13·8 | (7·3–20·3) |

| No response | 1/3 | 33·8 | (0–88·9) | 0/2 | - | |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Income per household per month (ZAR15 = US$1)C | ||||||

| No income | 387/766 | 46·2 | (40·7–51·7) | 140/524 | 27·6 | (22·8–32·5) |

| ZAR 1–500 | 334/614 | 51·0 | (45·7–56·4) | 116/293 | 45·0 | (38·0–52·1) |

| ZAR 501–2 500 | 1294/2720 | 45·3 | (42·6–48·0) | 435/1436 | 28·8 | (25·7–31·9) |

| ZAR 2501–6000 | 549/1197 | 43·1 | (39·9–46·3) | 183/705 | 25·6 | (20·9–30·3) |

| >ZAR 6000 | 169/432 | 36·5 | (28·7–43·2) | 51/242 | 23·3 | (17·4–29·2) |

| No Response | 222/536 | 40·8 | (35·5–46·2) | 89/347 | 25·2 | (20·1–30·2) |

| 0·0126b | 0·0002b | |||||

| Away from home for >1 month in the last 12 months | ||||||

| Yes | 311/623 | 46·1 | (40·3–52·0) | 113/398 | 31·6 | (24·5–38·7) |

| No | 2633/5620 | 43·9 | (42·0–45·8) | 899/3135 | 27·6 | (25·5–29·7) |

| 0·4492b | 0·2934b | |||||

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single, not living with partner | 2380/5055 | 44·2 | (42·4–46·1) | 840/3168 | 26·1 | (24·0–28·2) |

| Legally married | 258/682 | 34·8 | (30·0–39·7) | 68/180 | 35·8 | (26·1–45·4) |

| Single, but in stable relationship | 158/246 | 60·7 | (53·2–68·3) | 63/125 | 41·7 | (30·6–52·7) |

| Living as husband and wife | 97/175 | 53·2 | (44·4–62·1) | 39/61 | 71·1 | (57·1–85·1) |

| Widowed | 44/76 | 60·5 | (45·1–75·8) | 3/6 | 45·1 | (20·7–69·5) |

| Divorced | 10/17 | 68·8 | (45·5–92·2) | 0/4 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Separated, but still legally married | 8/14 | 57·2 | (26·7–87·7) | 1/3 | 8·2 | (0–26·8) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Sexual behaviour characteristics | ||||||

| Ever had sex | ||||||

| Yes | 2818/5447 | 49·6 | (47·6–51·6) | 944/2855 | 32·5 | (30·1–34·9) |

| No | 137/818 | 11·2 | (8·7–13·8) | 70/692 | 9·0 | (6·4–11·7) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Age at first sex | ||||||

| <18 years | 741/1441 | 49·2 | (45·5–52·9) | 292/1058 | 26·0 | (22·8–29·3) |

| ≥18 years | 1044/2123 | 47·7 | (44·8–50·6) | 210/670 | 32·0 | (27·8–36·1) |

| 0·5134b | 0·0229b | |||||

| Age of partner at first sex | ||||||

| <18 years | 150/304 | 47·4 | (39·8–54·9) | 313/1088 | 27·2 | (23·8–30·7) |

| ≥18 years | 1503/3025 | 47·5 | (45·1–49·9) | 164/541 | 31·4 | (26·3–36·5) |

| 0·9716b | 0·1914b | |||||

| Condom use at first sex | ||||||

| Yes | 381/860 | 38·5 | (33·8–43·1) | 87/538 | 15·1 | (10·8–19·4) |

| No | 2311/4337 | 52·0 | (49·9–54·1) | 800/2156 | 37·2 | (34·1–40·3) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Number of sex partners in the last 12 months | ||||||

| One | 1916/3837 | 47·5 | (45·3–49·8) | 566/1633 | 33·1 | (30·0–36·1) |

| More than one | 109/182 | 57·7 | (47·5–67·8) | 150/481 | 32·4 | (27·1–37·7) |

| 0·0515b | 0·8256b | |||||

| Lifetime sex partners | ||||||

| None | 137/818 | 11·2 | (8·7–13·8) | 70/692 | 9·0 | (6·4–11·7) |

| One | 533/1546 | 31·8 | (28·8–34·7) | 93/421 | 25·5 | (20·1–30·9) |

| One-to five | 1638/2853 | 56·1 | (53·5–58·7) | 373/1197 | 28·1 | (24·5–31·8) |

| More than five | 204/280 | 76·8 | (70·3–83·3) | 314/760 | 42·2 | (37·4–46·9) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Ever tested for HIV | ||||||

| Yes | 2513/4939 | 47·8 | (45·8–50·0) | 754/2326 | 31·5 | (28·8–34·2) |

| No | 442/1326 | 27·2 | (23·7–30·6) | 260/1221 | 20·4 | (17·5–23·4) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| HIV status (self-report) | ||||||

| Negative | 618/2989 | 19·1 | (17·3–21·0) | 205/1719 | 11·7 | (10·2–13·3) |

| Positive | 1833/1845 | 99·1 | (98·4–99·7) | 504/522 | 97·1 | (95·1–99·1) |

| Don’t know | 475/1385 | 28·3 | (24·9–31·8) | 297/1288 | 22·1 | (19·0–25·1) |

| No response | 29/46 | 66·5 | (47·0–86·0) | 8/18 | 36·8 | (13·0–60·5) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001 | |||||

| Ever used alcohol | ||||||

| Yes | 391/643 | 55·9 | (50·6–61·1) | 481/1432 | 32·1 | (29·3–35·0) |

| No | 2564/5622 | 42·9 | (41·0–44·9) | 533/2115 | 25·2 | (22·3–28·1) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0007b | |||||

| Condom use in the last 12 monthsd | ||||||

| Always | 594/994 | 55·9 | (50·6–61·1) | 196/593 | 31·9 | (26·8–36·9) |

| Never | 418/1032 | 42·9 | (41·0–44·9) | 165/469 | 32·9 | (26·1–39·8) |

| Sometimes | 1207/2324 | 55·9 | (50·6–61·1) | 439/1294 | 33·7 | (30·4–37·0) |

| <0·0001b | 0·8622b | |||||

| Biological or clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Ever diagnosed with tuberculosis | ||||||

| Yes | 251/274 | 93·1 | (89·8–96·5) | 150/203 | 72·1 | (62·6–81·7) |

| No | 994/1364 | 71·7 | (68·3–75·2) | 273/505 | 53·9 | (48·4–59·4) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0007b | |||||

| Ever diagnosed with any sexually transmitted infections (self-report) | ||||||

| Yes | 213/318 | 65·2 | (59·3–71·1) | 99/231 | 41·9 | (32–51·7) |

| No | 2742/5947 | 42·7 | (40·9–44·5) | 915/3316 | 26·9 | (24·6–29·1) |

| <0·0001b | 0·0065b | |||||

| Currently has a laboratory diagnosed sexually transmitted infectione | ||||||

| Yes | 2817/4919 | 55·3 | (53·3–57·3) | 913/1899 | 47·6 | (44·7–50·4) |

| No | 138 /1346 | 8·8 | (7·0–10·6) | 101/1648 | 6·0 | (4·6–7·4) |

| <0·0001b | <0·0001b | |||||

| Circumcised (men only) | ||||||

| Medical | NA | 158/1102 | 14·0 | (11·4–16·6) | ||

| Traditional | 49/139 | 35·4 | (24·6–46·1) | |||

| Don’t know | 3/6 | 57·6 | (13·1–100) | |||

| No | 800/2293 | 34·3 | (31·6–37·0) | |||

| 0·0035b | ||||||

| Ever pregnant (women only) | ||||||

| Yes | 2353/4391 | 52·2 | (50·0–54·4) | NA | ||

| No | 602/1872 | 25·1 | (22·1–28·2) | |||

| <0·0001b | ||||||

population-adjusted percentages;

p value for the association for variable with HIV status;

ZAR= South African Rand;

number of men and women who reported having sex in the last 12 months;

any laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and/or Mycoplasma genitalium DNA from self-collected swabs (women) and first-pass urine (men) samples and antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 2 and Treponema pallidum (syphilis);

Missing values were excluded from percentage calculation 95% CI= 95% confidence interval; NA= not applicable;

Table 3 presents the multivariable model exploring the association of factors with HIV positive status. Controlling for age, education, relationship status, number of lifetime partners and male circumcision status; a current laboratory diagnosis of any sexually transmitted infection (men: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 10·4, p<0·0001 and women: aOR 7·3, p<0·0001); one to five lifetime sex partners (aOR 1·7, p<0·0001); more than five lifetime sex partners (aOR of 3·9, p<0·0001), not being medically circumcised (aOR 1·7, p=0·0011) were associated with HIV. Completion of secondary schooling was protective for both men (aOR 0·6, p=0·0001) and women (aOR 0·8, p=0·0438).

Table 3:

Characteristics associated with HIV prevalence among men and women in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015

| Variable | Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | p value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | p value | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–19 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 20–24 | 2·1 (1·3–3·4) | 0·0016 | 2·2 (1·1–4·7) | 0·0339 |

| 25–29 | 3·9 (2·6–6·0) | <0·0001 | 5·3 (2·5–11·3) | <0·0001 |

| 30–34 | 7·5 (4·9–11·6) | <0·0001 | 9·9 (4·6–21·7) | <0·0001 |

| 35–39 | 7·9 (5·1–12·2) | <0·0001 | 13·2 (6·3–27·7) | <0·0001 |

| 40–44 | 6·3 (3·8–10·2) | <0·0001 | 14·9 (6·5–34·4) | <0·0001 |

| 45–49 | 2·8 (1·7–4·5) | <0·0001 | 5·7 (2·7–12·1) | <0·0001 |

| Education | ||||

| Incomplete secondary (Grade 8–11) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Completed secondary (Grade 12) | 0·8 (0·7–1·0) | 0·0438 | 0·6 (0·5–0·8) | 0·0001 |

| Tertiary (Diploma/degree) | 0·6 (0·4–0·9) | 0·0113 | 0·4 (0·2–0·8) | 0·0100 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Legally married | Ref | Ref | ||

| Single | 2·8 (2·2–3·7) | <0·0001 | 1·9 (1·2–2·9) | 0·0049 |

| Living as husband and wife | 2·1 (1·4–3·3) | 0·0011 | 3·6 (1·4–9·0) | 0·0071 |

| Widowed / Divorced | 2·8 (1·5–5·1) | 0·0011 | 0·4 (0·1–1·8) | 0·2295 |

| Lifetime sex partners | ||||

| One | Ref | |||

| One-to five | 1·7 (1·5–2·1) | <0·0001 | ||

| More than five | 3·9 (2·5–5·9) | <0·0001 | ||

| Refused or missing | 1·6 (1·3–2·0) | <0·0001 | ||

| Currently has a laboratory diagnosed sexually transmitted infectiona | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 7·3 (5·3–10·2) | <0·0001 | 10·4 (7·4–14·7) | <0·0001 |

| Circumcised (men only) | ||||

| Medical | NA | Ref | ||

| Traditional / Don’t Know | 1·1 (0·6–2·1) | 0·6875 | ||

| No | 1·7 (1·2–2·3) | 0·0011 | ||

any laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis and/or Mycoplasma genitalium DNA from self-collected swabs (women) and first-pass urine (men) samples and antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 2 and Treponema pallidum (syphilis).

Table 4 shows the CD4 cell counts and viral load distribution among HIV positive individuals. Overall, 8·0% of women and 17·2% of men (p<0·0001); those on ART, 5·6% of women and 17·0% men, (p<0·0001) and those not on ART, 10·1% women and 17·3% men, (p<0·0001) had CD4 cell counts below 200 cells per μl. The median viral load in women was 67 and in men 4940 copies per mL, whilst the geometric mean viral load in women was 163 and in men 811 copies per mL. In both women and men on ART the median and geometric mean viral load were below 20 copies per mL, whilst those not on ART the median viral load was 8177 and 27042 and the geometric mean was 1966 and 8084 copies per mL in women and men respectively. Overall, 54.8% of women and 41.9% of men (p<0.0001) and those on ART 87.2% of women and 83.9% men (p=0.3670) had achieved viral suppression.

Table 4:

CD4 cell count and HIV viral load in HIV positive men and women in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015

| Women (N=2955)a |

Men (N=1014)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Population-weighted %,(95% CI) | n | ||||

| Overall CD4 cell count (cells per μL) | ||||||

| <200 | 247 | 8·0 | (6·7–9·3) | 178 | 17·2 | (13·9–20·5) |

| 200–349 | 449 | 15·1 | (13·6–16·7) | 261 | 23·9 | (20·4–27·3) |

| 350–499 | 639 | 21·1 | (19·0–23·1) | 243 | 23·9 | (20·5–27·2) |

| >500 | 1594 | 55·8 | (53·6–58·1) | 327 | 35·1 | (31·3–38·9) |

| On antiretroviral therapy (cells per μL)b | ||||||

| <200 | 75 | 5·6 | (4·1–7·1) | 54 | 17·0 | (12·0–21·9) |

| 200–349 | 164 | 13·6 | (11·2–16·0) | 90 | 24·7 | (18·6–30·7) |

| 350–499 | 267 | 20·6 | (17·5–23·7) | 82 | 23·6 | (17·9–29·4) |

| >500 | 737 | 60·2 | (56·4–64·0) | 114 | 34·8 | (28·9–40·6) |

| Not on antiretroviral therapy (cells per μL)b | ||||||

| <200 | 172 | 10·1 | (8·1–12·1) | 124 | 17·3 | (12·8–21·8) |

| 200–349 | 285 | 16·4 | (14·1–18·7) | 171 | 23·4 | (19·3–27·4) |

| 350–499 | 372 | 21·5 | (18·7–24·3) | 161 | 24·0 | (19·3–28·8) |

| >500 | 856 | 52·0 | (49·0–55·0) | 213 | 35·3 | (30·3–40·3) |

CD4 cell count data are missing for 27 women and five men.

Self-report.

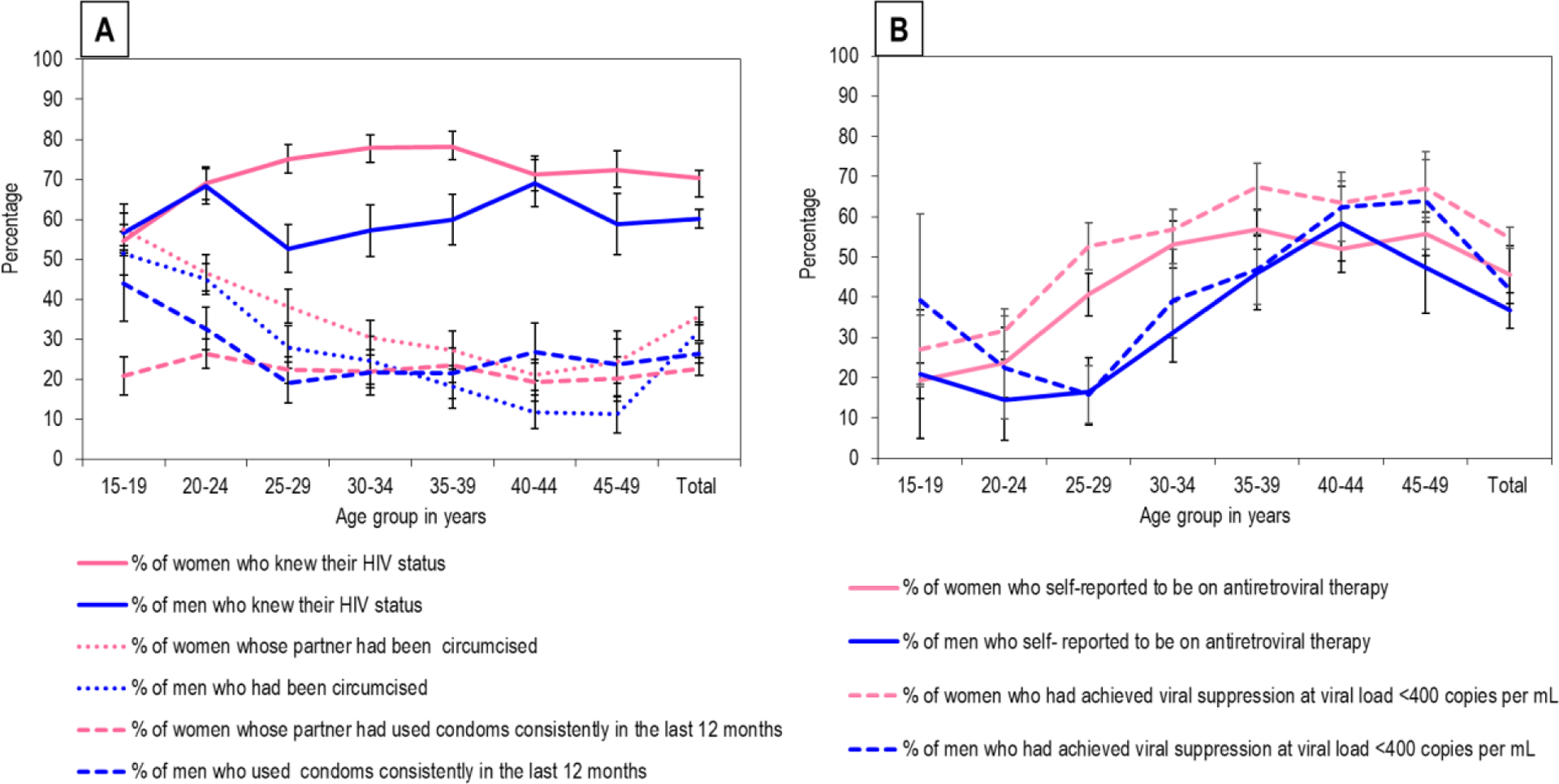

Figures 2 A and B (Appendix 3) show the self-reported coverage of HIV prevention and treatment strategies by gender and age. Knowledge of HIV status was 70·3% for women and 60·1% for men (p<0·0001). Consistent condom use use with sex acts in the last 12 months was 22·7% for women and 26·5% for men (p=0·0033), 35·7% of women reported that their male partner was circumcised whilst 31·9% of men were medically circumcised (p<0·0001). Knowledge of HIV status, consistent condom-use with sex acts in the last 12 months and being medically circumcised was higher among younger participants and declined among men 25 years and older. Among HIV positives, ART use was 45·6% in women and 36·7% in men, (p=0·0003), whilst 54·8% of women and 41·9% (p< 0·0001) of men had achieved viral suppression.

Figure 2: Coverage of HIV prevention strategies among men and women in a rural and peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–2015.

(A) Coverage of consistent condom use with sex acts in the last 12 months, medical male circumcision and knowledge of HIV status among all participants (n=9812) (B) Coverage of ART and associated viral suppression among HIV positive participants (n=3969); (*self- report; error bars =95% confidence interval)

Discussion

This first comprehensive community-based survey undertaken in Vulindlela and the Greater Edendale areas of the uMgungundlovu district, KZN, demonstrated substantially high HIV prevalence among 15–49-year old men and women (36·3%) and a disproportionate burden among women compared to men (44·1% vs 28·0%). Furthermore, prevalence in this community was twice the national average of 18·8% and exceeded the 27·9% reported provincially for the same age groups just three years prior.2 Current national and provincial HIV prevalence estimates mask the heterogeneity within the country and hence are less useful in the current context of geographic location-based approaches to a better understanding of the epidemic.15 The age-sex disaggregation of prevalence highlights the persistent features of the epidemic: young women across each two-year age band had higher prevalence compared to young men in the same age group and by age 24 years, one in three young women were HIV positive compared to one in nine young men. More importantly, these key features of the epidemic in this community in 2014 are concerning as we have failed to protect young women and alter these exceptionally high prevalence and patterns of infections.

Comprehensive packages of evidence-based approaches of consistent condom use, MMC, knowledge of HIV status and more recently the expanded use of HIV treatment to prevent transmission to sexual partners, are the main tools for reducing risk of HIV acquisition.20 However, these tools have not been scaled-up to maximise coverage and density to impact the epidemic. Further, condoms and MMC are male-centric strategies with little or no decision-making options for women. Scientific advances using PrEP to reduce HIV risk provides one of the first opportunities for a high-impact woman-initiated HIV prevention option in this generalized, hyper-endemic epidemic setting. Whilst South Africa became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to have full regulatory approval and included PrEP in the national HIV programme, PrEP was initially reserved for high risk individuals such as sex workers,8 but is expected to become increasingly available for all young women to benefit from.21

Our findings show that a high proportion of households had tangible infrastructure amenities of clean drinking water and electricity yet lacked adequate sanitation facilities. These factors may not have direct causal association with HIV acquisition and transmission but highlight the health and social development challenges facing communities, that could lead to risk-taking behaviours. Major structural and socioeconomic barriers potentially lead to psychological stress, poor living conditions and disrupted social cohesion within families and communities. Our study community is burdened with densely populated households, high rates of school attrition, low marriage rates, majority of individuals not living with their partners and extensive financial dependency on social support grants; these social factors likely contribute to high levels of unemployment and low levels of income.22 Although not directly measured in this study, these factors may motivate or discourage HIV related risk and protective behaviours, including the uptake of HIV services.

We identified several factors contributing to vulnerability to HIV. Independent risk factors among women and men included older age, being unmarried, current STIs (defined as laboratory diagnosed STIs), not completing secondary (high) schooling, having more than one lifetime sex partners and not being circumcised (men). Not completing high school is complex, as many structural level factors such as poverty, inadequate financial resources, single and or double parent orphans, child headed households, patriarchal societies could modify risk and influence retention in schools.23 Premature attrition from schools could lead to behaviours placing young women at risk for unintended pregnancies, STIs and HIV. Whilst these associations are significant and biologically plausible, highlighting the complex multilevel interaction across the life-course, the cross-sectional design of our study limits the temporal relationship of these factors with HIV positive status. For HIV prevention messaging our findings are important as they guide the messaging to address, educate and inform on risk behaviours, crucial to reducing HIV incidence, specifically among adolescent girls and young women.

Studies at the individual-level have shown MMC and ART to interrupt viral transmission and reduce HIV acquisition.24,25 However, at the population-level, the impact of MMC is dependent on coverage and risk behaviours, and the impact of ART is moderated by the percentage of HIV positive individuals who know their status, initiate treatment and achieve viral suppression. The present study revealed largely suboptimal coverage of biomedical strategies of MMC and ART as well as knowledge of HIV status and consistent condom use, notably substantially low among men 25–29 years. Yet, men medically circumcised were less likely to be HIV positive and those on ART more than 80% had achieved viral suppression. We also found that at least 40% men and 20% of women with HIV had low CD4 cell counts and were not on ART despite being eligible at the time of the study.5 It is possible that even with marked immunosuppression, a substantial proportion of individuals were not aware of their HIV positive status or had delayed seeking HIV care timeously; thus, improving coverage through universal test (through expanded and innovative HTS) and treat strategy11 would reduce transmission potential over time.12

The last several years have seen dramatic improvements in ART provision with several countries in sub-Saharan Africa reaching almost 80% coverage of adults 15 years and older.26,27 As ART is now a reasonably affordable and scalable intervention having the potential to almost instantaneously produce considerable improvements in population health, it is imperative that HIV programmes set targets with a focus on sustaining and scaling up ART provision to match the magnitude of the epidemic in the region. In this community social, economic and environmental challenges could potentially undermine the success of programmes; hence, understanding patient and provider perspective are necessary to minimise barriers to uptake of ART and, together with strong monitoring and evaluation to ensure sustainability of programmes. Furthermore, as ART is being rolled-out at a rapid rate and the overwhelming number expected to be on ART, novel strategies to encourage behaviours to sustain adherence and long term viral suppression will be crucial to potentially fast-tracking epidemic control.28

HIV surveillance has evolved substantially, and the inclusion of robust measurements provide a nuanced understanding of the evolving epidemic and guide programming and scale–up of prevention strategies. Whilst summary estimates are useful to understand the epidemic at an ecological level, disaggregation by gender and age provides a more precise understanding of the epidemic for targeted interventions.2,29,30 Furthermore, as ART coverage expands, population viral load increasingly becomes a powerful proxy for monitoring ART implementation. The population-level median and geometric mean viral load in diagnosed and undiagnosed individuals provide insights into dynamics of the epidemic and it is expected that the higher the coverage of ART, the larger the number of individuals with lower viral load in the population, and the lower the number of new infections. However, both the geometric mean and median mask individuals in sexual networks with excessively high viral load levels who potentially sustain the epidemic.31–33 This study demonstrates that across all age groups, men were less likely to know their HIV positive status, less likely to be on ART and less likely to have achieved viral suppression.10 Whilst it may be easier to reach out to young women through a public health approach such as integrated school health and family planning services with an offer of PrEP over the period of high risk, it is far more challenging to reach out to men through similar approaches and the importance of reaching out to men through strong messaging and targeted community and workplace programmes.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Whilst the large sample size was representative of the community and the robust sampling strategy minimised clustering of infections from households and overestimation of HIV prevalence, the differential recruitment of men and women may bias our overall HIV prevalence. Despite similar gender distribution of the study sample across all age groups and proportionately like the Census population,19 we analysed our data by gender to minimise potential bias from aggregated data. Our refusal rate at the household and the individual level was lower than most community-based surveys that require substantial adjustments for non-participation.34 Stigma and discrimination in this community may have influenced individuals’ decision on disclosure of ART use which could inadvertently disclose to family and community members and therefore self-reporting of ART use and sexual risk behaviours could be socially desirable rather than a true reflection of reality. It is also possible that the sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests could misclassify our HIV test results, however, we utilised multiple assays to minimise misclassification. The cross-sectional design of our study limits the ability to conclude the temporal relationship between the self-reported factors with HIV positive status. Furthermore, our findings are limited to Vulindlela and the Greater Edendale areas of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and not necessarily generalizable to other hyperendemic settings. Nevertheless, our data provides a reasonable representation of the community.

In conclusion, HIV prevalence in this community is among the highest in the world. Our findings of the large number of individuals already on ART underscores the importance on the extent of the future care burden for HIV positives. The sub-optimal coverage of HIV prevention strategies including ART, the risk for future onward HIV transmission remains elevated as individuals with high viral load potentially sustain the epidemic. It is vitally important to scale-up targeted risk-based HIV prevention strategies exponentially, to attain HIV epidemic control in the region.

Supplementary Material

Table 5:

HIV RNA viral load in HIV-positive men and women in a rural and periurban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2014–15

| Women (N=2955)a |

Men (N=1014)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall HIV RNA viral load | ||

| Median, IQRb | 67 (<20–13816) | 4940 (<20–45448) |

| Geometric mean copies per mL,(range) c | 163 (<20–5400000) | 811 (<20–2300000) |

| Viral suppressione (n/N, percentage, (95% CI) | 1574/2955 54·8 (52·0–57·5) | 401/1014 41·9 (37·1–46·7) |

| On antiretroviral therapyd | ||

| Median (copies per mL, IQR)b | <20 (<20–<20) | <20 (<20–36) |

| Geometric mean copies per mL, (range) c | <20 (<20–1000000) | <20 (<20–516440) |

| Viral suppressione (n/N, percentage, (95% CI) | 1086/1251 87·2 (84·6–89·8) | 284/341 83·9 (78·5–89·3) |

| Not on antiretroviral therapyd | ||

| Median (copies per mL, IQR)b | 8177 (179–30808) | 27042 (3434–76519) |

| Geometric mean copies per mL, (range) c | 1966 (<20–5400000) | 8084 (<20–2300000) |

| Viral suppressione (n/N, percentage, (95% CI) | 488/1704 27·4 (24·3–30·5) | 117/673 17·5 (13·5–21·6) |

Plasma viral load data are missing for nine women and four men

To calculate the geometric mean and median HIV RNA viral load, HIV-positive participants with undetectable viral load or <20 copies per mL were assigned a value of 1 or 10 copies per mL respectively and reported as <20 copies per mL (ie, the lower limit of quantification for the assay).

Viral suppression at viral load <400 copies per mL

Self-report. Percentages are population-weighted.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

South Africa with a national HIV prevalence of 18·8% in the age group 15–49 years experiences a special and unique typology of a generalised hyperendemic epidemic. To reduce the number of new HIV infections and associated morbidity and mortality the South African government has rolled-out intensified HIV prevention strategies towards epidemic control. We searched PubMed and MEDLINE up to June 20, 2017 for South African HIV surveillance studies that assessed HIV prevalence and the contemporaneous coverage of HIV prevention strategies such as knowledge of HIV status through HIV testing services (HTS), condom use, medical male circumcision (MMC), coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among people living with HIV (PLHIV) and HIV viral suppression. We used search terms individually and in combination. Search terms were “HIV”, “AIDS”, “surveillance”, “prevalence”, “HIV prevention strategies”, “knowledge of HIV status”, “condom use”, “ART uptake or coverage”, “antiretroviral therapy” and “viral suppression”. We identified reports or studies on the annual National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Prevalence Surveys, annual Africa Centre Demographic Information System in the Hlabisa district from northern KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) community surveys, the South African National household surveys of 2002, 2005, 2008 and 2012; the Mbongolwane and Eshowe HIV Impact Survey in KZN, South African Agincourt Health and Socio-demographic Surveillance in Mpumalanga and the South African Orange Farm survey, however, the findings from these surveys are not generalisable to communities beyond the survey areas. To guide targeted roll-out and scale-up of HIV prevention interventions more precisely and cost-efficiently, location-based HIV measures are vital.

Added value of this study

Our findings from the study area show a high overall population-level HIV prevalence of 36·3% among 15–49 year-old men and women; and a disproportionate burden among women (44·1%) compared to men (28·0%). The age-sex disaggregation of prevalence highlights the consistently higher prevalence in young women compared to young men and by age 24 years, one in three young women were HIV positive compared to one in nine young men. Whilst men and women self-reported engaging in HIV prevention strategies including HTS, condom use, MMC and sustainable ART with associated viral suppression, the coverage of these strategies were sub-optimal given the high HIV burden in this community.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results emphasise an important missed opportunity and gap in the coverage of HIV prevention strategies that potentially fuels new infections. Intensified approaches to seek, identify and link individuals to interventions will be critical to realise the goal of achieving epidemic control in this region.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to all household members and individual study participants who through their participation have contributed immensely to the understanding of the HIV epidemic in this region. We acknowledge the ongoing support of Ms May Zuma-Makhonza, District Manager the uMgungundlovu Health District, Members of the Provincial Department of Health, Mr Lesley S Sakuneka, the HIV/AIDS Programme Coordinator for uMgungundlovu District Municipality; Provincial Health Research and Knowledge Management, Local Traditional Leadership and community members for their support throughout the study. A special thanks to the study staff for the field work, laboratory and Primary Health Care clinic staff in the district. A special tribute to the late Dr Mark Colvin for his important contribution leading to this work.

Study sponsorship and funding Statement:

Supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of operative agreement 3U2GGH000372–02W1. ABMK is supported by the joint South Africa–US Program for Collaborative Biomedical Research from the National Institutes of Health (R01HD083343).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer:

Publisher's Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data. 2017; Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf: Accessed 8 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya D et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Cape Town, HSRC Press; 2014; Available at: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20final.pdf: Accessed 20 August 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.South Africa National Department of Health. The 2013 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Prevalence Survey South Africa. 2013; Available at: https://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Dept-Health-HIV-High-Res-7102015.pdf: (Accessed 15 December 2016).

- 4.Padayatchi N, Naidoo K, Dawood H, Kharsany ABM, Abdool Karim Q. A Review of Progress on HIV, AIDS and Tuberculosis South African Health Review eds Padarath A, Fonn S 2010; Available at http://www.hst.org.za/publications/south-african-health-review-201087-100 Accessed 20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Department of Health South Africa. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults 2015; Available at: http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/ART%20Guidelines%2015052015.pdf: Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 6.Horwood C, Vermaak K, Butler L, Haskins L, Phakathi S, Rollins N. Elimination of paediatric HIV in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: large-scale assessment of interventions for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Bull World Health Organ 2012; 90(3): 168–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynn A, Bristow CC, Ross D, Schenker I, Klausner JD. A program evaluation report of a rapid scale-up of a high-volume medical male circumcision site, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2010–2013. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekker L-G, Rebe K, Venter F, et al. Southern African guidelines on the safe use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in persons at risk of acquiring HIV-1 infection. S Afr J HIV Med 2016; Available at: http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/hivmed/article/view/455: Accessed 12 October 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90-90-90 An Ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014; http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf: Accessed 8 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grobler A, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Puren A, Kharsany ABM. Progress of UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets in a district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, with high HIV burden, in the HIPSS study: a household-based complex multilevel community survey. The Lancet HIV 2017: DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17) 30122–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.South African National Department of Health. Implementation of the Universal Test and Treat Strategy for HIV Positive patients and differentiated care for stable patients 2016; Available at: http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/22%208%2016%20Circular%20UTT%20%20%20Decongestion%20CCMT%20Directorate%20(2).pdf: Accessed 24 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(13): 921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(6): 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Strategy 2016–2021: On the Fast-Track to end AIDS. 2015; Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20151027_UNAIDS_PCB37_15_18_EN_rev1.pdf: Accessed 20 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Location, location: connecting people faster to HIV services. 2013; Available at: http://unaids.org.vn/en/location-location-connecting-people-faster-to-hiv-services/: Accessed 8 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones A, Cremin I, Abdullah F, et al. Transformation of HIV from pandemic to low-endemic levels: a public health approach to combination prevention. Lancet 2014; 384(9939): 272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR Blueprint: Creating an AIDS-free Generation. 2012; Available at: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/pepfar_blueprint_2012.pdf: Accessed 16 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharsany AB, Cawood C, Khanyile D, et al. Strengthening HIV surveillance in the antiretroviral therapy era: rationale and design of a longitudinal study to monitor HIV prevalence and incidence in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics South Africa. Census 2011; Statistical release P0301.4 Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2011; Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03014/P030142011.pdf: Accessed 10 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Department of Health South Africa. Guidelines for Expanding Combination Prevention and Treatment Options: Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Test and Treat (T&T). 2016, 8 December; Available at: http://www.google.co.za/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=5&ved=0ahUKEwi1q-L8ifHWAhVYGsAKHenGDQMQFgg4MAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.avac.org%2FSA_PrEP_National_Guidelines&usg=AOvVaw2yNcNlS839nRf_3HlOUcJH: Accessed 15 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cluver LD, Orkin FM, Meinck F, Boyes ME, Sherr L. Structural drivers and social protection: mechanisms of HIV risk and HIV prevention for South African adolescents. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19(1): 20646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kidman R, Anglewicz P. Why Are Orphaned Adolescents More Likely to Be HIV Positive? Distinguishing Between Maternal and Sexual HIV Transmission Using 17 Nationally Representative Data Sets in Africa. J Adolesc Health 2017; 61(1): 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaizot S, Huerga H, Riche B, et al. Combined interventions to reduce HIV incidence in KwaZulu-Natal: a modelling study. BMC Infectious Diseases 2017; 17(1): 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong X, Kigozi G, Ssekasanvu J, et al. Association of Medical Male Circumcision and Antiretroviral Therapy Scale-up With Community HIV Incidence in Rakai, Uganda. JAMA 2016; 316(2): 182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nsanzimana S, Kanters S, Remera E, et al. HIV care continuum in Rwanda: a cross-sectional analysis of the national programme. The Lancet HIV 2015; 2(5): e208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaolathe T, Wirth KE, Holme MP, et al. Botswana’s progress toward achieving the 2020 UNAIDS 90-90-90 antiretroviral therapy and virological suppression goals: a population-based survey. The Lancet HIV 2016; 3(5): e221–e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19(1): 21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huerga H, Van Cutsem G, Ben Farhat J, et al. Who Needs to Be Targeted for HIV Testing and Treatment in KwaZulu-Natal? Results From a Population-Based Survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73(4): 411–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Olivé FX, Angotti N, Houle B, et al. Prevalence of HIV among those 15 and older in rural South Africa. AIDS Care 2013; 25(9): 1122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbeck J, Tanser F. Community viral load as an index of HIV transmission potential. The Lancet HIV 2016; 3(4): e152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller WC, Powers KA, Smith MK, Cohen MS. Community viral load as a measure for assessment of HIV treatment as prevention. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13(5): 459–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira T, Kharsany AB, Graf T, et al. Transmission networks and risk of HIV infection in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a community-wide phylogenetic study. The Lancet HIV 2017; 4(1): e41–e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larmarange J, Mossong J, Barnighausen T, Newell ML. Participation dynamics in population-based longitudinal HIV surveillance in rural South Africa. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(4): e0123345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.