Abstract

Aims:

To assess the biopsychosocial effects of participation in a unique, combined arts- and nature-based museum intervention, involving engagement with horticulture, artmaking and museum collections, on adult mental health service users.

Methods:

Adult mental health service users (total n = 46 across two phases) with an average age of 53 were referred through social prescribing by community partners (mental health nurse and via a day centre for disadvantaged and vulnerable adults) to a 10-week ‘creative green prescription’ programme held in Whitworth Park and the Whitworth Art Gallery. The study used an exploratory sequential mixed methods design comprising two phases – Phase 1 (September to December 2016): qualitative research investigating the views of participants (n = 26) through semi-structured interviews and diaries and Phase 2 (February to April 2018): quantitative research informed by Phase 1 analysing psychological wellbeing data from participants (n = 20) who completed the UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure pre–post programme.

Results:

Inductive thematic analysis of Phase 1 interview data revealed increased feelings of wellbeing brought about by improved self-esteem, decreased social isolation and the formation of communities of practice. Statistical analysis of pre–post quantitative measures in Phase 2 found a highly significant increase in psychological wellbeing.

Conclusion:

Creative green prescription programmes, using a combination of arts- and nature-based activities, present distinct synergistic benefits that have the potential to make a significant impact on the psychosocial wellbeing of adult mental health service users. Museums with parks and gardens should consider integrating programmes of outdoor and indoor collections-inspired creative activities permitting combined engagement with nature, art and wellbeing.

Keywords: creative activities, green prescriptions, mental health service user, mixed methods, museum intervention, psychological wellbeing, social prescribing

Introduction

The wide-ranging benefits of social prescription on psychological health have been well established.1,2 Consequently, there is a growing impetus for social interventions that support psychosocial health outcomes, such as community-based referral to non-clinical provision involving creative and cultural activities, physical exercise or educational opportunities.3,4 Given that a fifth of consultations with a general practitioner (GP) are for psychosocial rather than medical problems,5 social prescribing has become an important means by which healthcare professionals can ‘seek to address the non-medical causes of ill health with non-medical interventions’ (p. 5).3 As an illustration of current interest in the UK in non-medical interventions, a new independent not-for-profit organisation, the National Academy of Social Prescribing, has been set up by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. The Academy’s mission is to develop and advance social prescribing to promote health and wellbeing at local and national levels.6

As part of the National Health Service (NHS) Long Term Plan, NHS England has published a summary guide to social prescribing, regarded as a key component of Universal Personalised Care – the choice and control that people have over the way their care is planned and delivered.7 As part of its Long Term Plan for the next 10 years, NHS England aims to recruit over 1000 trained social prescribing link workers within primary care networks by 2020/2021 and to integrate social prescribing into the personalised care remit with the objective of referring 900,000 people to such schemes by 2023/2024 (p. 25).8 Furthermore, social prescribing in general practice, described as the use of referral and signposting to non-medical services in the community, is listed as one of 10 high impact actions needed to release time for GP care.9 Other high impact actions related to social prescribing include active signposting that provides patients with a first point of contact to direct them to an appropriate source of help, such as web and app-based portals, and supporting people to play a greater role in their own health.

Arts on Prescription has a long history in the UK and the evidence base continues to grow, demonstrating a range of psychosocial outcomes that include supporting mental health recovery; combatting social isolation for people with mild to moderate anxiety and depression; as well as increased levels of empowerment and improved quality of life.1,10 A review of Arts on Prescription studies illustrated a body of evidence indicating that participation in creative activities can promote health and wellbeing, quality of life, levels of empowerment and social inclusion, and positively impact people with mental ill-health.10 Furthermore, the authors proposed that creative arts contribute to the health of the wider community, not just the individual. There is also good evidence to show that creative engagement in museums supports health and wellbeing, quality of life, social inclusion and lifelong learning. An extensive Museums on Prescription study, that carried out 12, 10-week programmes of museum-based sessions in seven central London and Kent museums with 115 participants, found significant wellbeing improvements.3 Participants in the study, who were aged 65–94 and considered to be at risk of social isolation, rated highly the experiences of feeling absorbed and enlightened by the sessions and commented on the opportunities afforded by the museum activities to meet new people, learn new information and develop new skills.

Another type of social prescribing, ‘green prescription’ where outdoor spaces are used to improve health and wellbeing, is beginning to gain momentum, with a potential for impact across the life span.11 Green prescriptions work under the same premise as social prescriptions, focusing on therapeutic engagement with nature-based interventions. A Scandinavian systematic review of 38 nature-assisted therapy programmes located three main types of intervention: horticultural therapy, wilderness therapy and unspecified nature-assisted therapy.12 The authors found small but robust evidence to suggest that these different types of nature-based therapies were relevant public health interventions. Effects of these therapies included psychological, social and physical goals across diverse patient groups, with reduced measurable symptoms of disease in some cases, for instance, obesity and schizophrenia. An Australian review, using an expert elicitation process, categorised 27 distinct nature-based interventions.13 Interventions were split into two categories: those that aimed to promote general wellbeing and prevent chronic health conditions through interaction with nature and those that aimed to treat specific physical, mental or social health and wellbeing issues through behavioural and environmental change. The review found that a key characteristic of nature-based health interventions is that a single intervention can potentially improve wellbeing across a range of domains. Nature prescriptions can promote physical activity leading to positive health outcomes, while contact with nature can have an additional restorative effect on mental wellbeing. As such, nature prescriptions can have significant impact as not only do they have multiple effects, they may have potential in terms of protective factors. Across both reviews, the authors called for more research to investigate the effectiveness of such programmes to promote their wider usage across public health.

A 2013 review evaluated the published literature on nature-based activities and found reliable evidence of the positive effects of gardening for mental health. The evidence included reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety, and a range of self-reported benefits across emotional, social, physical, occupational and spiritual aspects of the lives of mental health service-users.14 Studies focused on mental health outcomes give further insight into the multiple effects of nature-based interventions that go beyond the benefits of contact with nature or physical exercise. Indeed, an additional potential positive effect of nature-based interventions is that they tend to be designed as social activities and therefore have the potential to mitigate social isolation and enable engagement with a person’s community.15 Qualitative studies further consolidate understanding of the psychotherapeutic mechanisms for how nature prescriptions can impact wellbeing, and mental health in particular. The social and occupational dimensions of activities are strongly associated with feelings of belonging allied with decreasing isolation and increasing social inclusion for people experiencing mental health issues.16 In addition, as meaningful activities with opportunities for knowledge and skills developments, nature-based interventions help to consolidate self-reliance and bolster self-esteem;17 factors known to improve individual psychosocial wellbeing.18 Conversely, poor self-esteem can be an indicator for the development of mental health disorders.19 Improvements in self-esteem can be supported by programme designs that enable self-expression, personal growth and connectedness (with self and others) through meaningful occupation.20

The current UK-based study utilised the trend by museums and art galleries starting to use their outdoor spaces with a wider focus on wellbeing activities.3,21 Since these activities are designed and delivered by museums, they are able to utilise the unique characteristics of their sites to bring together horticulture and gardening with creativity and culture. This article sets out to examine the potential of such a combination in a mental health intervention with adults, an area of practice not yet investigated. The current research was situated in a park adjoining an inner-city art gallery. It focused on a group project of dual engagement in green activity outdoors (including planting and clearing) and creative, arts-based activities indoors responding to collections with broad links to nature themes (including painting, print making and ceramics). The study was developed as a part of a larger research initiative called Not So Grim Up North, a collaboration between researchers at University College London and two museum partners, the Whitworth Art Gallery and Manchester Museum, part of the University of Manchester, and Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums. The current study reports on a project called ‘GROW: Art, Park & Wellbeing’, delivered by the Whitworth Art Gallery since 2015. The aim of this study was to explore the health and wellbeing outcomes derived from engagement in a combined programme of horticulture and creative, arts-based activities. In this sense, the study is unique and original in considering the dual effects of indoor and outdoor spaces, and the combination of arts- and nature-based activities. It was hypothesised for the quantitative phase of the study that measures of wellbeing would increase significantly reflecting positive improvements, such as social inclusion, that might be identified in the qualitative phase.

Methods

Design

The project used a two-stage design following exploratory sequential mixed methods (p. 16),22 where qualitative data collected in Phase 1 (September–December 2016) shaped quantitative data collection in Phase 2 (February–April 2018). Phase 1 used participant observation and in-depth, semi-structured interviews (Supplemental Appendix 1) derived from ethnographic methods to capture data in nature-based interventions.23 Qualitative data comprised researcher and facilitator observation, interviews with participants (n = 10 at programme-end; n = 1 at 3- and 6-month follow-up), facilitators (n = 2) and volunteers (n = 1); and structured diary entries from participants (n = 12) and facilitators (n = 2). Phase 2 used a quantitative within participants design with an independent variable of pre- and post-intervention (Weeks 1 and 10) and dependent variable of psychological wellbeing score on the UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure,24,25 specifically the positive generic wellbeing measure with high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .81).

Participants

Phase 1 participants (n = 26) and Phase 2 participants (n = 20), with a mean age of 53 and age range of 26 (44–70 years), comprised 60% White, 30% Black and 10% Mixed race, with approximately equal numbers of males and females. They were recruited on the basis of accessing local mental health or social services through a community mental health nurse or day centre providing support to vulnerable and disadvantaged adults. Attendance across the project was varied with no single participants attending all 10 sessions of the programme. A different group of participants took part in each phase. Participant attrition reduced the Phase 1 sample size (n = 16: males = 8); Phase 2 sample size remained constant (n = 20: males = 11).

Materials

Materials included the participant information leaflet, consent form, museum activity schedule, interview protocol, weekly diaries with guideline questions and the UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure, a positive mood scale where participants rate each of six mood items (Active, Alert, Enthusiastic, Excited, Happy and Inspired) on a 5-point scale (1 = ‘I don’t feel’; 2 = ‘I feel a little bit’; 3 = ‘I feel fairly’; 4 = ‘I feel quite a bit’; and 5 = ‘I feel extremely’).24,25

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained for the research (Health Research Authority Ethics ID 199643). Participants were referred to the dual programme of outdoor horticultural activities and indoor nature-based creative activities, and were sent the museum schedule, consent form and information leaflet in advance of the programme. Informed consent was obtained by the research team prior to the start. The programme was coordinated by the Whitworth Gallery Cultural Park Keeper and delivered by a horticultural specialist, an arts tutor and a museum volunteer. The groups met in Whitworth Park and used the museum spaces to connect the indoors with the outdoors and nature. The 2-h sessions, comprising talks, demonstrations and practical activities, were held on consecutive Tuesdays over 10 weeks. A typical session started with a 15-min briefing prior to group work, with a 15-min break halfway through followed by group or individual work. Outdoor sessions comprised practical demonstrations followed by hands-on activities (e.g. using and maintaining garden tools, then cutting back herbaceous perennials) whereas indoor sessions included gallery visits or object handling followed by producing creative responses (e.g. looking at texture in an artwork, then using textured painting techniques to produce studies of parkland trees). Participants, facilitators and researchers kept weekly diaries with guideline questions to record their experiences. In Phase 1, participants and staff were interviewed at programme end with one participant interviewed at 3- and 6-month follow-up (not discussed here due to the small sample). In Phase 2, measures were completed before Session 1 and after Session 10. Data were anonymised and stored in a secure database.

Results

For Phase 1, qualitative findings were derived from inductive thematic analysis of participant and facilitator diaries and interviews,26 using NVivo v11, and for Phase 2, quantitative findings resulted from statistical analysis of pre–post intervention scores from UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure,24,25 using IBM SPSS v25.

Phase 1: qualitative findings

An inductive approach was chosen as there are no other published studies on combined arts- and nature-based programmes. The inductive thematic analysis involved a six-phase approach consisting of familiarisation with interview transcripts and diaries, generation of initial codes, searching for themes among codes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and producing qualitative findings.26 Three themes were inductively generated: building a sense of community, decreasing social isolation and supporting self-esteem. These themes worked together in shaping the collective experience of the intervention. As one participant elaborated,

I did feel a lot happier, every time I finished the session. I felt a sense of achievement very much so, self-esteem. . . a sense of belonging as well and doing something that refers to myself and especially with other people. It just made me feel not only more solid within my beliefs in myself and what I can do but a lot more connected, because it was done in a group session as opposed to a one-to-one.

Examples of participant responses from across each of the three themes (Tables 1, 2 and 3) are discussed in turn below.

Table 1.

Codes and quotes associated with building a sense of community

| Theme | Codes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Building a sense of community | Groups forming Connections Shared experience Learning Positive mood Green Space Art |

‘Like I say, the […] group that came mostly seemed kind of

happy and, bubbly and connected with each other anyway from

the beginning right through to the end’.

(Facilitator) ‘Enjoyed mixing with group, growing with them’. ‘So how we feel and how we’re affected and so how our diagnosis or experiences of mental health issues might affect us and how we feel and how we act. So, quite important and still conversations that you wouldn’t normally have . . .’ ‘What I’ve learnt here, especially the herbs and the gardening, I loved that’. ‘Outside it’s a kind of big park, so you have . . . it’s just being close to nature in some ways. So, it feels alright, it’s great’. ‘Yes, because we were working . . . yes, the physical connection with the earth, the soil, I didn’t think I would like that at all, but it’s got an amazing satisfaction. I felt a lot more able to understand my mother being so fond of gardening after the sessions, or other people who are gardening obsessed’. ‘I learned about art as I say and how to produce prints and how to dry some flowers. How to have the nature and the flowers and the nature itself can be, can be a source of art and inspiration for art’. |

Table 2.

Codes and quotes associated with decreasing social isolation

| Theme | Codes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Decreasing social isolation | Connections with group members and

facilitators Routine and structure of getting out the house |

‘I always see a couple of the people at the group. Yeah. And

hopefully when the group opens again, I’d like to

return’. ‘I found out I could work as well in a team . . .’ ‘It’s just a feeling of doing something in a group really. It’s basically that, doing an activity in a group which gave me a little bit, improved my confidence a little bit as the weeks went by’. ‘Yes, yeah. It’s just a bit, just a tiny bit easier being with strangers, just a tiny bit though. But yeah it’s helped me a bit’. ‘I liked getting up in the morning. I liked the fact that I had something to do’. ‘It has provided some structure and an opportunity to be in a group with others while doing something interesting’. |

Table 3.

Codes and quotes associated with supporting self-esteem

| Theme | Codes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting self-esteem | Confidence Agency and ability Purpose Meaningful occupation Motivation Participation |

‘While I was doing the course, my self-esteem has been sort

of raised considerably to what it was’. ‘Confidence really. The confidence to get out and about again. To meet new people. It was really a kick up the backside to get out’. ‘I was feeling a bit nervous, a bit scared, not realising, it wasn’t anything really to worry about. So, actually taking part helped my confidence a lot more’. ‘Doing something I felt was worthwhile and sort of taking on board the praise I’d been getting from them, and, sort of just getting out of bed and coming here is a sort of reward in itself’. ‘I’ve come out my shell which is really major, do you know what I mean? ‘Cos usually I just curl up and feel sorry for myself and not go anywhere. Instead, I’ve been coming here, trying to get out the house, trying to get a life, there’s only so much you can do with my illness, you know, but, it’s great. I love it’. ‘Connected with other people and, and in the process you find. . . you learn about yourself also. Because it’s a group – other people become sort of a mirror and only in, in social situations a person can learn about himself’. ‘I can do things that I like’. ‘Don’t need to be negative. I can do’. ‘I am able to help others’. ‘If you are participating in life, that is interacting to other living beings, and then that enhances you. It doesn’t make you less in any way, you know, maintaining or enhancing [wellbeing], yeah’. |

Sense of community

Across interviews, participants described how the programme had fostered a sense of community over the 10 weeks that had helped them to feel relaxed and enjoy the programme, as many commented that they were nervous on first arrival. Participants noted how the sense of community was facilitated by a number of related characteristics of the programme, first from knowledge and reassurance of taking part in activities with other people with shared experience of mental health difficulties:

It was very important to relate to people, that we had a common ground factor and that was our mental health experiences. Any other art group that wasn’t focused around mental health, I would never be able to have the same chats and the same connection and the same understanding and empathy.

This shared understanding of each other played a key role in building a sense of community in the programme. Although mental health was not discussed explicitly in the sessions, participants were aware that they shared a tacit understanding of mental health experiences. Support and sharing tended to happen spontaneously during breaks or activities on participants’ own terms. Positive engagement was enhanced by facilitators and museum staff who recognised that participants were more than just their diagnosis.

Second, the programmes provided new, hands-on skills in both horticulture and arts-based practice, and this learning appeared to contribute to building a sense of community. In both set of activities, there were opportunities to learn together and further a common goal (e.g. planting) and for individual achievements (e.g. painting in response to a museum object or artwork). This unique combination of group and individual activities appeared to be key to producing positive outcomes for participants. As one participant reflected,

We all come together didn’t we so . . . so at the end of it we all come as one. We were all together singly. Like the flowers, I suppose.

Decreasing social isolation

Another effect of the intervention was related to enabling participants to gain motivation and a positive reason to leave their homes. Some participants led relatively isolated lives, while others reported spending a great deal of time at home alone, linked to unemployment and/or current mental health issues. Participants felt that the intervention gave them routine and structure with an opportunity to engage positively with others, which in turn decreased the sense of social isolation and was felt to support wellbeing and the potential of recovery. As one participant explained,

if you give people structure, then they don’t . . . they won’t get bored you see, and also it gives them some meaning, as well. And, especially if they are interacting with other people, that also helps people in their recovery, if people have to recover from something. Or, even maintaining wellbeing, interacting with others. I mean, nobody’s isolated, you know, because then that’s not helpful to the wellbeing.

The programme could also be said to have an effect beyond the sessions as it gave participants something positive to look forward to during the week.

Self-esteem

Another key area related in interviews was the development of self-esteem through the programme. Several participants noted this in relation to becoming more outgoing as the session progressed, for example:

I’ve come out my shell which is really major, do you know what I mean? ‘Cos usually I just curl up and feel sorry for myself and not go anywhere.

Self-esteem was derived through social interactions around group activities outdoors where participants would help and support one another in activities (e.g. helping someone to dig), as well as supporting each other through informal, social discussion around the activities, both giving participants a sense of purpose. This was further enabled by the facilitation that modelled inclusive, supportive practice. As one participant summarised,

This is the point, if you’re being supported, listened to, helped, it gives you self-confidence and self-worth and you try to do the same thing for [other participants].

Self-esteem was also derived from the new learning and skills development about art and horticulture. One participant reflected on how they felt proud that their work could be enjoyed by other visitors to the museum park:

I felt very useful because I was helping the nature first and then I was going to make some people happy when they come out and they look very nice in in the spring. And people will enjoy it, enjoy the flowers that I put down on the ground.

Phase 2: quantitative findings

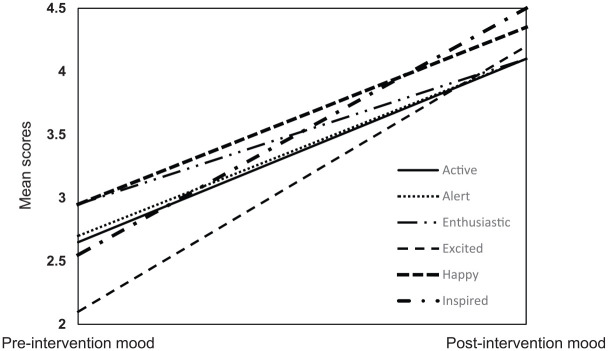

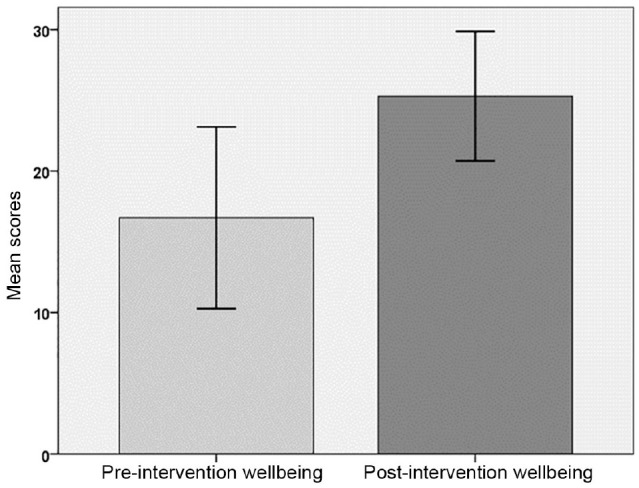

Pre–post intervention UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure total scores (out of 30) and individual mood item scores (each out of 5) were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistical tests. Descriptive statistics showed that mean total scores for wellbeing increased postintervention compared with preintervention (Table 4, Figure 1). An inferential statistical paired t test on approximately normal data showed that the pre–post increase in wellbeing was highly significant, t(19) = 6.96, p < .001, one-tailed. Scores for each of the six mood items (Active, Alert, Enthusiastic, Excited, Happy and Inspired) were examined separately (Table 5). There was no missing data. Each of the separate mood items increased highly significantly postsession compared with presession and t tests showed no significant differences between individual mood items. The largest improvement across the intervention was for the word ‘Excited’ closely followed by ‘Inspired’ (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Descriptive and inferential statistics for wellbeing

| N | Mean (SD) | t (df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention wellbeing | 20 | 16.70 (6.42) | ||

| Postintervention wellbeing | 20 | 25.30 (4.58) | ||

| Pre–post wellbeing improvement | 8.60 | 6.96 (19) | <.001 |

SD: standard deviation; df: degrees of freedom.

Figure 1.

Pre–post intervention wellbeing improvement (error bars ± 1 standard deviation (SD)).

Table 5.

Descriptive and inferential statistics for individual mood items

| N | Mean (SD) | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention Active | 20 | 2.65 (1.18) | |||

| Postintervention Active | 20 | 4.10 (0.91) | |||

| Pre–post Active improvement | 1.45 | 5.90 | 19 | <.001 | |

| Preintervention Alert | 20 | 2.70 (1.26) | |||

| Postintervention Alert | 20 | 4.10 (0.91) | |||

| Pre–post Alert improvement | 1.40 | 5.98 | 19 | <.001 | |

| Preintervention Enthusiastic | 20 | 2.95 (1.19) | |||

| Postintervention Enthusiastic | 20 | 4.10 (0.97) | |||

| Pre–post Enthusiastic improvement | 1.15 | 4.72 | 19 | <.001 | |

| Preintervention Excited | 20 | 2.10 (1.07) | |||

| Postintervention Excited | 20 | 4.20 (0.70) | |||

| Pre–post Excited improvement | 2.10 | 5.94 | 19 | <.001 | |

| Preintervention Happy | 20 | 2.95 (1.05) | |||

| Postintervention Happy | 20 | 4.35 (0.75) | |||

| Pre–post Happy improvement | 1.40 | 6.29 | 19 | <.001 | |

| Preintervention Inspired | 20 | 2.55 (1.20) | |||

| Postintervention Inspired | 20 | 4.50 (0.83) | |||

| Pre–post Inspired improvement | 1.95 | 7.94 | 19 | <.001 |

SD: standard deviation; df: degrees of freedom.

Figure 2.

Pre–post intervention individual mood item improvement.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the health and wellbeing outcomes derived from a combined programme of nature-based horticulture and arts-based responses to museum collections as part of a creative green prescription. As Phase 1 produced a range of positive responses, it was hypothesised for the quantitative analysis, Phase 2 of the study, conducted two years later with another group of participants, that psychological wellbeing would increase significantly and reflect positive improvements identified initially through thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis of participant and facilitator interviews in Phase 1 revealed three main themes: building a shared sense of community, decreasing social isolation and supporting self-esteem. Each of these interacted to form the collective experience of the intervention; the sense of community supported a decrease in social isolation while self-esteem was boosted through social interaction. The sense of community was enabled by knowledge of shared experience but notably, this was not the main focus of the programme; rather, it was the types of activity and the non-clinical indoor and outdoor spaces of the museum that supported a sense of community first and foremost. The new learning gained from the programme, across both nature and arts topics, also contributed to a shared sense of community and individual self-esteem, thereby reducing feelings of isolation commonly reported by participants before the start of the project.

Although mental wellbeing was not mentioned explicitly by all participants, most of the themes they expressed had positive outcomes with many related to improvements in quality of life and individual, psychological wellbeing; consequently, it was appropriate to use the positive mood UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure for Phase 2 of the study.24,25 Furthermore, support for self-esteem and allied confidence, agency, ability and sense of purpose are theorised to improve individual psychosocial wellbeing.15 It was interesting that all of the six mood items on the Wellbeing Measure increased significantly after the 10-week programme, particularly ‘Excited’ and ‘Inspired’, that linked into the overall creative and outdoor experience of the intervention. These increases in positive mood, specifically in enthusiasm, inspiration, excitement and happiness, are conjectured to have arisen through the social, interactive and creative content of the programme. ‘Active’ also contributed to overall wellbeing, which could be related to the physical elements of the programme, in particular the outdoor horticultural activities. As such, and drawing on the wider literature, it can be speculated that the combined programme also had some physical health benefits, though these were not measured directly.

As a creative green prescription for adults with mental health issues, this study focused on engagement with a dual, arts- and nature-based intervention, and found predominantly positive biopsychosocial outcomes. Findings from the research need to be interpreted tentatively, however, due to the small sample size and the lack of a control group experiencing life as usual without the intervention. The unique aspect of this programme was its delivery across two different environments, the park and the museum spaces. A future study, therefore, might compare the effects of a single intervention, arts- or nature-based with the effects of a combined programme. Currently, it can only be speculated that there were specific synergies between the dual aspects of the intervention, most notably in the creative and multisensory engagement,27 that are likely to have supported positive outcomes alongside the social aspects of the project and the opportunities for new learning.

Within the literature, both arts- and nature-based interventions independently have been found to mitigate social isolation and enable engagement with a person’s community.3,10,11 In this study, these activities were effectively combined to produce similar outcomes. At the same time, there is some indication that this unique combination of physical and creative activities, and the outdoor and indoor museum spaces, may allow for additional benefits, as participants were able to engage in individual and group pursuits. Another aspect of note from this study is the sharing of past and current experiences of mental health that appeared to enhance social ties. While this intra-group sharing did not necessarily improve participants’ relationships with people outside of their groups in the wider community, it could provide an area for further study.

A strong theme from this study was that the intervention bolstered self-confidence and self-esteem, aligning with other research.14 Given that poor self-esteem can be an indicator for the development of mental health disorders,16 it seemed pertinent that participants with mental health issues in this study should benefit from improved self-esteem. In addition, a challenge with common mental health disorder (anxiety and depression) is that it can co-occur with other factors such as social isolation, because people are reluctant to leave their homes, which in turn can lead to a lack of physical exercise from not going out. From this perspective, it is relevant to highlight the large significant pre–post increase in the feeling of being active, as shown in the UCL Museum Wellbeing Measure mood item analysis.

While there is limited previous research comparing arts- and nature-based interventions, these two forms of social prescribing appear to bring about similar health and wellbeing benefits, and further research is warranted to explain the underlying neuro-biopsychosocial mechanisms.27 Similarly, the creative and multisensory aspects of these seemingly different types of activity need to be better understood, as do the connections between creativity, health and wellbeing, especially in relation to the neuro-biopsychosocial mechanisms underpinning creative health.

Conclusion

The Creative Health report argues that the arts and creativity can encourage a healthy lifestyle, aid recovery and support major health and social care challenges including ageing, long-term conditions, loneliness and mental health.28 Research on engaging with nature shows similar advantages,11,12 and here we report on the benefits of an intervention that includes both arts- and nature-based activities. Given the positive improvements for the two groups of participants in this study, held in a museum with adjacent parkland, it appears that green prescriptions, combining creative arts- and nature-based activities, have the potential to significantly impact the lives of adult mental health service users. Museums with outdoor spaces need to recognise the health, wellbeing and quality of life benefits in green prescribing, and the opportunities for combining creative outdoor and indoor activities using their spaces and collections.27 The advantages that museums with outdoor spaces have over single green environments, such as forests or farms, is that they are not necessarily restricted by weather conditions, as collections-inspired activities can be continued indoors. Findings from this study link to the body of research on social prescribing,1 where community referral can be used to support psychosocial outcomes.2,3 Further research exploring interconnections between creativity, arts, nature, health and wellbeing outcomes is warranted to fully explain the dual, and potentially synergistic, benefits of creative arts and green prescriptions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix1_PPH_R1 for Art, nature and mental health: assessing the biopsychosocial effects of a ‘creative green prescription’ museum programme involving horticulture, artmaking and collections by LJ Thomson, N Morse, E Elsden and HJ Chatterjee in Perspectives in Public Health

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Whitworth Art Gallery’s Cultural Park Keeper, Francine Hayfron and the Arts for Health Manager, Wendy Gallagher; also the horticultural specialists and museum volunteers who supported the programmes, the community mental health and day centre staff who referred participants to the project, and in particular the participants who consented to take part in the research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Research and data collected from the Not So Grim Up North project and was approved by the University College London Ethics Committee (Study Ref.: 8297/001), and the Health Research Authority (IRAS IC 199643).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This study was conducted as part of the Not So Grim Up North project funded by Arts Council England (2015–2018; Grant: 29250851). The GROW Project and the Whitworth Gallery’s creation of the Art Garden has been funded by Jo Malone, London.

ORCID iDs: Linda J Thomson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9685-3678

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9685-3678

Esme Elsden  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3867-3588

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3867-3588

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

LJ Thomson, UCL Division of Biosciences, University College London, London, UK.

N Morse, School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

E Elsden, UCL Division of Biosciences, University College London, London, UK.

HJ Chatterjee, UCL Division of Biosciences, University College London, 507B Darwin Building, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

References

- 1. Chatterjee HJ, Thomson LJ, Lockyer B, et al. Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health 2017; 10: 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Polley M, Pilkington K. A review of the evidence assessing impact of social prescribing on healthcare demand and cost implications. London: University of Westminster; Available online at: https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/q1455/a-review-of-the-evidence-assessing-impact-of-social-prescribing-on-healthcare-demand-and-cost-implications (2017, accessed 4 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomson LJ, Lockyer B, Camic PM, et al. Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults. Perspect Public Health 2018; 138(1): 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. King’s Fund. What is social prescribing? Available online at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing (2017, accessed 8 November 2019).

- 5. Parkinson A, Buttrick J. The role of advice services in health outcomes: evidence review and mapping study. London: London Advice Services Alliance and The Low Commission; Available online at: https://www.scie.org.uk/prevention/research-practice/getdetailedresultbyid?id=a11G000000G6QAsIAN (2015, accessed 4 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Academy for Social Prescribing. Available online at: http://www.socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/about-us (2019, accessed 2 December 2019).

- 7. NHS England. Social prescribing and community-based support: summary guide. Available online at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/social-prescribing-community-based-support-summary-guide.pdf (2019, accessed 2 December 2019).

- 8. NHS England. The NHS long term plan. Available online at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (2019, accessed 2 December 2019).

- 9. NHS England. General practice forward view. Available online at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf (2016, accessed 2 December 2019).

- 10. Bungay H, Clift S. Arts on prescription: a review of practice in the UK. Perspect Public Health 2010; 130(6): 277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buck D. Gardens and health: implications for policy and practice. London: King’s Fund; Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David_Buck10/publication/303436076_Gardens_and_health_Implications_for_policy_and_practice/links/5742e22a08ae9ace8418b42e.pdf (2015, accessed 2 December 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Annerstedt M, Wahrborg P. Nature-assisted therapy: systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scand J Public Health 2011; 39(4): 371–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shanahan DF, Astell-Burt T, Barber EA, et al. Nature-based interventions for improving health and wellbeing: the purpose, the people and the outcomes. Sports 2019; 7(6): 141–61. Available online at: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4663/7/6/141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clatworthy J, Hinds JM, Camic P. Gardening as a mental health intervention: a review. Ment Health Rev J 2013; 18(4): 214–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Howarth M, Rogers M, Withnell N, et al. Growing spaces: an evaluation of the mental health recovery programme using mixed methods. J Res Nurs 2018; 23: 476–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamant E, Waterhouse A. Gardening and belonging: reflections on how social and therapeutic horticulture may facilitate health, wellbeing and inclusion. Brit J Occup Ther 2010; 73: 84–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barton J, Griffin M, Pretty J. Exercise-, nature- and socially interactive-based initiatives improve mood and self-esteem in the clinical population. Perspect Public Health 2012; 132(2): 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. New Economics Foundation (NEF). National accounts of wellbeing: bringing real wealth onto the balance sheet. London: NEF, 2008. Available online at: www.nationalaccountsofwellbeing.org [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mann M, Hosman CMH, Schaalma HP, et al. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ Res 2004; 19(4): 357–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hui A, Stickley T, Stubley Baker F. Project earth: participatory arts and mental health recovery, a qualitative study. Perspect Public Health 2019; 139(6): 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kidd J, McAvoy EN. Immersive experiences in museums, galleries and heritage sites: a review of research findings and issues. Cardiff: School of Journalism, Media and Culture, 2019. Available online at: https://pec.ac.uk/assets/publications/PEC-Discussion-Paper-Immersive-experiences-Cardiff-University-November-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creswell JW. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd edn. London: Sage, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Brien L, Varley P. Use of ethnographic approaches to the study of health experiences in relation to natural landscapes. Perspect Public Health 2012; 132(6): 305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomson LJ, Chatterjee HJ. Measuring the impact of museum activities on wellbeing: developing the Museum Wellbeing Measures Toolkit. Mus Manage Curat 2015; 30: 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomson LJ, Chatterjee HJ. Assessing well-being outcomes for arts and heritage activities: development of a Museum Well-being Measures Toolkit. J Appl Arts Health 2014; 5: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chatterjee HJ. Partnership for health: the role of cultural and natural assets in public health. In: O’Neill M, Hopper G.(eds) Connecting museums. Oxford and New York: Routledge; 2019, pp. 112–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts Health Wellbeing Inquiry Report. Creative health: the arts for health and wellbeing. Available online at: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf (2017, accessed 2 December, 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix1_PPH_R1 for Art, nature and mental health: assessing the biopsychosocial effects of a ‘creative green prescription’ museum programme involving horticulture, artmaking and collections by LJ Thomson, N Morse, E Elsden and HJ Chatterjee in Perspectives in Public Health