Abstract

Cryptococcus gattii is a species that has received more recognition in the recent past as distinct from Cryptococcus neoformans. C gattii is known to cause meningeal disease in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Patients may be clinically asymptomatic until immunosuppressive conditions occur such as corticosteroid treatment or an HIV infection. HIV-associated cryptococcal infections are most often due to C neoformans. C gattii is found in a minority. Speciation and subtyping of Cryptococcus are not always accomplished. In many parts of the world, there is no availability for speciation of Cryptococcus. Travel history may provide a clue to the most probable species. This case demonstrates a case of C gattii meningitis with a multiplicity of complications. These include advanced HIV disease secondary to nonadherence, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, and superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. The patient represented diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas over time. Headache was the primary symptom in cryptococcal meningitis, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, and superior sagittal sinus thrombosis. All are discussed in detail as potential etiologies for the primary disease. Isavuconazonium is a relatively new broad-spectrum antifungal azole that was used as salvage therapy.

Keywords: Cryptococcus gattii, cryptococcal meningitis, superior sagittal sinus thrombus, thrombus in HIV, IRIS, isavuconazonium, azoles

Introduction

There are approximately 1 million cases of cryptococcosis each year worldwide and an estimated 650 000 associated deaths. Patients with advanced HIV disease comprise the majority.1-3

Cryptococcus has 37 known species but only 2 have been identified as pathogenic for cryptococcosis: C neoformans and C gattii. In 1970, C gattii was first described in Australia as a subspecies of C neoformans. It is a fungus associated with several ecologic niches.4-6 In 1999, C gattii emerged in British Columbia and the northwest United States. C gattii was recognized as a separate species from C neoformans in 2002.7

C neoformans is globally ubiquitous and accounts for nearly all meningeal infections in patients with HIV. C gattii has a more restricted distribution and accounts up to 15% of cryptococcal meningeal infections in endemic areas. The geographic range appears to be expanding with the continued study of C gattii.6,8

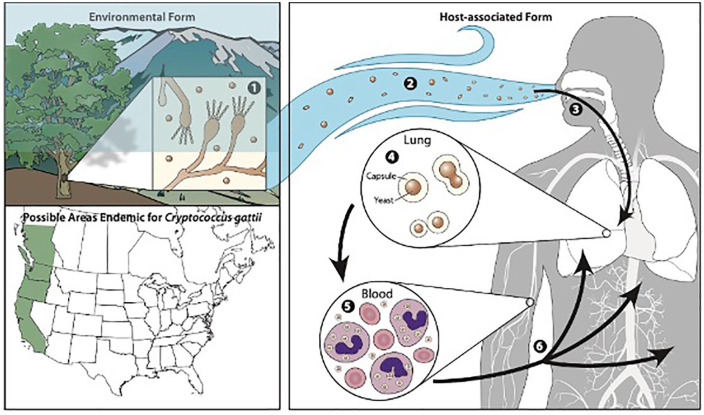

C neoformans and C gattii are encapsulated, heterobasidiomycetous fungi. The asexual form is recovered from clinical cases and is an encapsulated yeast that reproduces by budding.9 The respiratory tract is the primary portal of entry.9 Lymphohematogenous dissemination is responsible for seeding other organs including the meninges (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Encapsulated yeast inhaled into the respiratory tract. Lymphohematogenous dissemination.4

The lungs and the central nervous system (CNS) are the most common clinical sites of infection.2,9 Involvement of the parenchyma of the brain and meninges occurs in 40% to 86% of patients.10 Characteristic manifestations of CNS disease include meningitis, cryptococcomas, and spinal cord granulomas. Patients typically present with signs and symptoms of meningitis including fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, focal neurologic deficits, memory loss, or change in consciousness including cloudy/delirium, obtundation/stupor, and coma.9,11

One of the most critical determinants of outcome for cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is the control of intracranial pressure (ICP). Approximately 50% of HIV-infected patients with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis demonstrate an elevated baseline ICP >250 mm H2O of CSF. Lumbar puncture (LP) is recommended. An opening pressure of ≥250 mm H2O with symptoms warrants medical therapy. CSF drainage should be performed sufficiently to achieve a closing pressure of <200 mm H2O or 50% reduction of initial opening pressure.1,12

Neuroimaging is performed in patients with suspected cryptococcal meningitis.1,9 It does not alter management once cryptococcus is diagnosed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred in patients with HIV disease and may demonstrate leptomeningeal enhancement or focal brain disease.9 LP for high ICP is much more important to both follow and treat elevated ICP.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in cryptococcosis typically reveals a lymphocytic pleocytosis with elevated protein and decreased glucose levels. Cell counts vary from <20 cells/cmm to >100 cells/cmm.13,14 Low lymphocyte proliferative responses after stimulation with antigens are particularly noted in persons with active HIV disease. The CSF formula is that of chronic meningitis and is, therefore, the differential diagnosis.15

Mycologic diagnosis is accomplished by a variety of methods including positive India ink examination of CSF and blood, fungal cultures, and cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) detection in blood and spinal fluid.9,14

Management of C gattii meningitis is approached with consideration for 3 risk groups: HIV-infected individuals, organ transplant recipients, and ostensibly immune normal hosts. For each respective risk group, therapeutic algorithms have been articulated. This includes an induction phase, consolidation phase, and a maintenance phase. Induction therapy for meningoencephalitis involves fungicidal regimens, such as a polyene and flucytosine. It is followed by suppressive regimens using fluconazole. Recognition of increased ICP is critical and should be addressed as a separate problem from meningitis. See reference guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).1

The host response to C gattii depends on the competency of the host’s innate and adaptive immune systems. Host immunodeficiencies of the innate system may eventuate into clinical cryptococcal disease if there is macrophage failure. For the adaptive immune system, cryptococcal disease progression is facilitated in the setting of a predominately Th-2 response. There is a depletion of CD4+ T-helper (Th)-1 and Th-17 cells, as well as an increase in Th-2 cells. Failure to produce a Th-1 dominate response means failed host protection against cryptococcal infection.

HIV infection may be considered a failure of host cellular responses in the progressed phase of disease. Initially, however, HIV selectively infects CD4+ T-cells incognito and replicates intracellularly. It is undetected by the innate or the adaptive systems. There is pathogenic hyperactivation and proliferation of infected CD4+ T cells specific for antigens other than HIV. Eventually, CD4+ T-cell depletion results and accelerates HIV disease progression.16

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is an immunologic exacerbation based on improved host response to antiretroviral therapy. Potential treatment challenges related to IRIS are well described in HIV and cryptococcal meningeal coinfection.8,9 Similar to cryptococcal meningitis and HIV-encephalitis, the presenting symptoms commonly include headache, fever, and meningismus.8 Increased ICP, hydrocephalus, and systemic inflammation can also occur.

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is the rarest complication of venous thrombosis in cryptococcal meningitis and is difficult to diagnose.17,18 Complaints of headaches require cerebral vascular imaging for diagnosis. Evidence-based recommendations indicate anticoagulation treatment to reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications and death. The American Heart Association and American Stroke Association recommend anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months in provoked CVT, and 6 to 12 months in unprovoked CVT.18

CVT occurs at an annual incidence of 3 to 5 per million and tends to affect women and younger individuals.17 Risk factors for CVT include thrombophilia, infection, trauma, immobilization, reproductive (especially puerperium and pregnancy), malignancy, medications, inflammatory, hematological, endocrine, systemic, and intracranial abnormalities.18 Multiple risk factors of thrombosis may coexist as demonstrated in our case (advanced HIV disease, IRIS, and cryptococcus infection). The impact of multiple risk factors for venous thrombosis and its implications for management highlights the need for early comprehensive risk assessment.

Prophylactic strategies are considered. A heightened awareness of the potential difficulty in achieving adequate anticoagulation due to drug-drug interaction in patients on antiretroviral regimens is merited.

Methods

Kern Medical Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for review of the patient’s record. A literature search was conducted on PubMed, ResearchGate, Google Scholar, and major journal databases including Infectious Diseases Society of America, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Clinical Infectious Diseases. The following search terms were applied: Cryptococcus gattii, cryptococcal meningitis, superior sagittal sinus thrombus, cerebral venous thrombosis, thrombus in HIV, IRIS, isavuconazonium, azole side effects, ICP, and meningitis. Twenty-three reference articles were pulled.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old Caucasian man was diagnosed with HIV disease at another institution. He was nonadherent with antiretroviral therapy. One month after diagnosis, he presented to our institution with a severe headache and vomiting for 2 days.

On physical examination, his temperature was 37.3 °C, the pulse was 63 beats per minute, the respiratory rate was 21 breaths per minute, and the blood pressure was 140/91 mm Hg. The oxygen saturation was 97%, while the patient was breathing ambient air. He was in mild distress secondary to his headache. The general physical examination was unremarkable except for mild meningismus. The neurologic examination revealed normal mental status, cranial nerves, motor, gait, and balance.

Complete blood count with differential revealed lymphocytopenia (0.9 × 103 cells/µL) and routine chemistry was all normal except for mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase 56, alanine aminotransferase 141 units/L). His absolute CD4+ cell count was 38 cells/µL, and his HIV-1 RNA polymerase chain reaction revealed 35 284 copies/mL.

LP demonstrated an opening pressure of 340 mm H2O. The CSF analysis revealed a red blood cell count of 10 cells/cmm, a white blood cell count of 24 cells/cmm, lymphocytes of 73%, monocytes of 25%, neutrophils of 1%, and eosinophils of 1%. CSF glucose was 56 mg/dL and CSF protein was 75 mg/dL. Analysis of the CSF with India ink was positive for Cryptococcus species. Latex agglutination assay of CSF revealed a CrAg titer of 1:2046. Subsequently, the blood was positive for yeast. Serum assay revealed a CrAg titer of 1:4096.

Chest radiographs showed 2 irregular noncalcified densities of the right lower lobe with early central cavitation. Bron-choalveolar lavage confirmed Cryptococcus. Neuroimaging of the head was found to be negative.

Cryptococcal meningitis with pulmonary cryptococcoma was diagnosed. The patient was admitted and started on induction therapy with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (AmB) and oral flucytosine. After a 14-day course, he was discharged home on consolidation therapy with fluconazole and antiretroviral therapy. He was followed closely by the infectious disease clinic.1 Fungal isolates from blood and CSF were demonstrated to be C gattii.

The patient was hospitalized 9 times over a 12-month period for recurrence of fever, headache, and elevated ICP. Therapeutic LPs with CSF removal were intermittently required. A shunt was not placed due to inconsistent need for CSF drainage beyond a few days per episode.

The serum and CSF CrAg varied considerably over this time course. The maximum serum CrAg titer was 1:>4096 and the minimum was 1:256. The maximum CSF CrAg titer was 1:>2048 and the minimum was 1:8. Fluconazole levels were judged to be therapeutic (41.4 µg/mL serum fluconazole).

In the fourth hospitalization, a follow-up MRI of the brain demonstrated the development of cryptococcomas in the right posterior cerebellum and left temporal region. He was declared a therapeutic failure on fluconazole. Isolates were sent for sensitivity testing and results showed. Isolate sensitivity did not indicate drug resistance to any antifungal medications. Sensitivity results revealed AmB 0.5 µg/mL, fluconazole 4.0 µg/mL, natamycin 4.0 µg/mL, itraconazole 0.25 µg/mL, posaconazole 0.25 µg/mL, voriconazole 0.06 µg/mL, isavuconazole (ISA) 0.125 µg/mL. Induction therapy with AmB and flucytosine was reintroduced for 6 weeks. Subsequently, consolidation therapy with voriconazole 450 mg twice daily was initiated, at calculated dosing 6 mg/kg.

Salvage therapy with voriconazole, did not improve his fever, headache, or elevated ICP, prevent hospitalizations, or reduce the CSF or blood CrAg titers. He was adherent to therapy, but therapeutic levels were not achieved. After 3 months on voriconazole, the patient developed dysphagia that drew concern for possible onset of IRIS or worsening CNS cryptococcosis. Candida was not identified. The dysphagia self-resolved within 2 months, requiring no further workup.

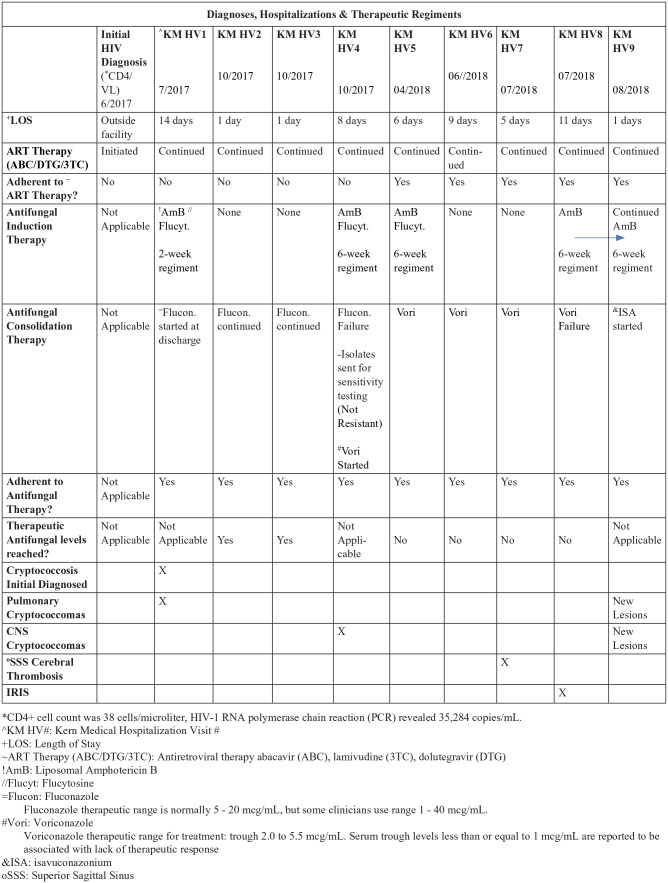

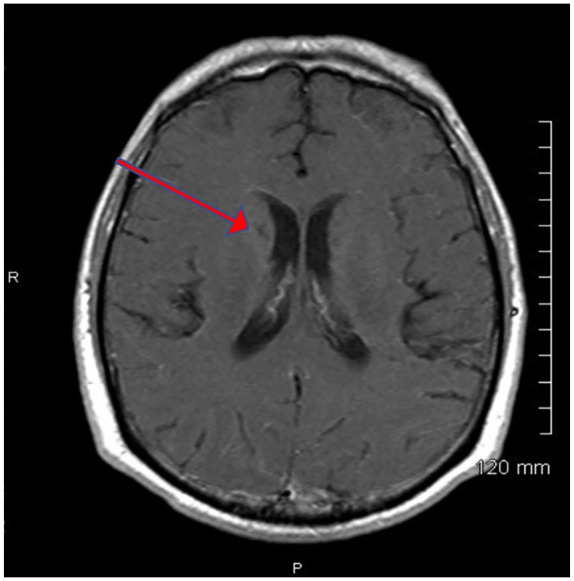

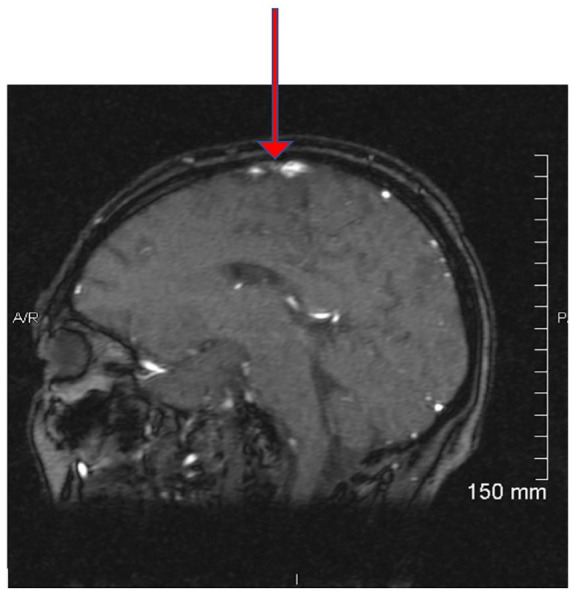

On the ninth hospitalization, and 1 year into treatment, an MRI of the head, revealed a new cryptococcoma (see Figure 2) and evidence of CVT. Magnetic resonance venography of the brain revealed a superior sagittal sinus thrombosis (see Figure 3). Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis was diagnosed and treated with anticoagulation therapy18 (see Figure 4 for diagnoses, hospitalizations and therapeutic regiments).

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of brain axial T1-weighted postcontrast with a red arrow showing the cryptococcoma.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance venography of brain showing a red arrow at the region of signal void of the sagittal 2-dimensional echo sequence source images, indicating a superior sagittal sinus thrombosis.

Figure 4.

Diagnoses, hospitalizations, and therapeutic regiments.

Most of the patient’s treatment was spent inpatient. He was started on multiple rounds of induction therapy, with regiment durations of 2 weeks or 6 weeks. Typically, he ended up in the emergency room with hospitalization for elevated ICP. Consolidation therapies included fluconazole and voriconazole, both of which failed, despite patient adherence. The therapeutic levels of antifungal medications were measured in the serum regularly throughout treatment. Therapeutic levels were achieved consistently with fluconazole antifungal treatment. Voriconazole was consistently identified at subtherapeutic in the serum despite patient adherence.

Isolate sensitivity did not suggest resistance, but his worsening condition warranted therapeutic modification. Antifungal therapy was switched from voriconazole to ISA 372 mg daily. Concern for IRIS was also increasing. Antifungal and antiretroviral therapies were continued in accordance to guidelines. No treatment holiday was taken. Treatment efforts were focused on ICP control, anticoagulation therapy for CVT, and continued adherence to antifungal therapy and medications for HIV.

The patient’s cryptococcal disease significantly improved since his transition to ISA. His headache and ICP improved. His absolute CD4+ cell count was 308 cells/µL. HIV-1 RNA polymerase chain reaction was not detected (<20 copies/mL: “not detected”) at his 1-year follow-up. The superior sagittal sinus thrombosis also resolved as demonstrated by magnetic resonance venography. There have not been any further hospitalizations since ISA therapy. He is adherent to ISA maintenance therapy and antiretroviral therapy 12 months after the ninth hospital discharge.

Discussion

Eight cases were found in the medical literature that recognize concomitant cryptococcal meningitis and CVT (Table 1). Five of these 8 cases involve individuals with HIV disease. Specifically, CVT was identified in the transverse sinus, superior sagittal sinus, and sigmoid sinuses in these 8 cases. C neoformans was found in half of the recorded cases, while 3 did not distinguish the species. We were unable to identify any instances of CVT involving C gattii. Additionally, none of these cases demonstrated the multiplicity of problems, extensive hospitalizations, and specific therapy as reported here.

Table 1.

Literature Review of Cryptococcal Meningitis.

| Study | Publishing type | Country | Age (years) | First symptom at presentation | Thrombosis location | IRIS | HIV disease (CD4+ count at time of diagnosis) | Cryptococcus meningitis and species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiansukhon et al19 | Poster | Thailand | 49 | Headache | Straight sinus Transverse and sigmoid venous sinuses bilaterally |

No | Yes CD4+ count: 70 cells/mm3 |

Yes Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Alejandra et al20 | Case report | Mexico | 21 | Headache | Left transverse sinus Bilateral sigmoid sinuses |

No | Yes CD4+ count: 96 cells/mm3 |

Yes No speciation |

| Senadim et al21 | Case report | Turkey | 19 | Headache | Right transverse sinus | No | No | Yes Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Kulkarni et al22 | Case report | India | 37 | Headache | Superior sagittal sinus Right transverse sinus Proximal internal jugular vein |

No | Yes CD4+ count: 24 cells/mm3 |

Yes No speciation |

| Ren et al23 | Case report | China | 31 | Headache | Bilateral transverse sinus Superior sagittal sinus Inferior longitudinal sinus |

No | No | Yes No speciation |

| Equiza et al24 | Case report | Spain | 45 | Headache, dizziness, nausea | Right transverse sinus Right sigmoid sinus |

No | Yes Unknown |

Yes Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Mohamed et al25 | Case report | Kenya | 40 | Headache, vomiting, blurred vision, painful Right eye | Distal superior sagittal sinus Left transverse sinus |

No | Yes CD4+ count: 9 cells/mm3 |

Yes No speciation |

| Kammeyer and Lehmann26 | Case report | United States | 61 | Headache, chills, night sweats | Left transverse and sigmoid sinus | No | No | Yes Cryptococcus neoformans |

| Heidari 2020 |

Case report | United States | 45 | Headache | Superior sagittal sinus | Yes | Yes CD4+ count: cells/mm3 |

Yes Cryptococcus gattii |

Abbreviation: IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

A failed induction or consolidation therapy requires a modification of dose, duration, or change of the therapeutic agent. Relapse of signs and symptoms during treatment should be carefully assessed to decipher between a failure to control fungal growth from drug resistance, or adherence, or IRIS. IRIS is an additional problem seen in HIV and can mimic therapeutic failure. Secondary resistance to fluconazole is an emerging problem in some geographical locations. This was not case in our patient as demonstrated by the sensitivity results (AmB 0.5 µg/mL, fluconazole 4.0 µg/mL, natamycin 4.0 µg/mL, itraconazole 0.25 µg/mL, posaconazole 0.25 µg/mL, voriconazole 0.06 µg/mL, isavuconazole 0.125 µg/mL). In persistent and relapse infections, isolates should be submitted for sensitivity testing and alternative agents should be considered.1

Low CD4+ counts (<200 cells/mm3), high viral load, and nonadherence to antiretroviral therapies are all risk factors for venous thrombosis. The most common risk factor is an ongoing infection. Proinflammatory cytokines, interluekin-6 and TNF-α, and endothelial activation have been implicated as underlying pathogenesis.27

Patients with advanced HIV disease with active C gattii meningitis appear to be at a higher risk for complications than persons without HIV disease. Individuals with Cryptococcus and HIV disease are at substantial risk for IRIS. IRIS is most probable in patients who have a very low CD4 count (<200 cells/mm3) when antiretroviral therapy is initiated. HIV therapy was difficult in this patient because he was not adherent at both the first institution and at our institution with initial therapies. With varying timelines of poor adherence and monitoring of his ART medications, all may have contributed to the development of IRIS. The timing of initiating antiretroviral therapy remains challenging.

Minor IRIS manifestations will typically resolve spontaneously in days to weeks. Major IRIS complications, such as CNS inflammation with increased ICP may require corticosteroids.1 The exactness of when to initiate antiretroviral therapy in the setting of cryptococcus and HIV coinfection to side skirt IRIS remains indeterminate. Recommendations propose a wide range of 2 to 10 weeks should be undertaken to accommodate this uncertainty.1

Conclusion

Patients with complex cryptococcal disease may have a multiplicity of complications that include increased ICP, hydrocephalus, and CVT. An additional complication is IRIS more common in HIV patients. The clinical presentation of these symptoms may overlap significantly. Significant effort is required to discern the appropriate therapeutic intervention to achieve resolution.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This case has been presented at the American Federation of Medical Research’s Western Conference, January 2019, as well as the Infectious Disease Association of California’s 34th Annual Fall Symposium, November 2019.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from the Kern Medical Institutional Review Board (Approval ID: 20026).

Informed Consent: Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was not obtained.

ORCID iD: Valerie F. Civelli  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1052-0144

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1052-0144

References

- 1. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322. doi: 10.1086/649858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pappas PG. Cryptococcal infections in non-HIV-infected patients. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2013;124:61-79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MacDougall L, Fyfe M, Romney M, Starr M, Galanis E. Risk factors for Cryptococcus gattii infection, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:193-199. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers Disease Control Prevention. Emergence of Crypto-coccus gattii—Pacific Northwest, 2004-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:865-868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Debess E, et al. Cryptococcus gattii in the united states: clinical aspects of infection with an emerging pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1188-1195. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39:155-168. doi: 10.1080/mmy.39.2.155.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kwon-Chung KJ, Boekhout T, Fell JW, Diaz M. (1557) Proposal to conserve the name Cryptococcus gattii against C hondurianus and C bacillisporus (Basidiomycota, Hymenomycetes, Tremellomycetidae). Taxon. 2002;51(4):804-806. doi: 10.2307/1555045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun HY, Alexander BD, Huprikar S, et al. Predictors of immune reconstitution syndrome in organ transplant recipients with cryptococcosis: implications for the management of immunosuppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:36-44. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis (Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2019:3146-3161. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-4801-3.00264-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aydin H, Kaya I. Raised intracranial pressure. In: Turgut M, Challa S, Akhaddar A, eds. Fungal Infections of the Central Nervous System. 1st ed. Springer; 2019:255. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-06088-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, Plum F, eds. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis and Treatment of Stupor and Coma. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; 2019:5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chayakulkeeree M, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. In: Hospenthal DR, Rinaldi MG, eds. Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Mycoses. 1st ed. Springer; 2007:273. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Satishchandra P, Mathew T, Gadre G, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic overviews. Neurol India. 2007;55:226-232. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.35683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SJ, Choi HK, Son J, Kim KH, Lee SH. Cryptococcal meningitis in patients with or without human immunodeficiency virus: experience in a tertiary hospital. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:482-487. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.3.482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bennett JE, Hoover SE. Chronic meningitis. In: Bennet J, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 1 9th ed. Elsevier; 2019:1220-1225. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-4801-3.00090-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deeks SG, Walker BD. The immune response to AIDS virus infection: good, bad, or both? J Clin Invest. 2004;113:808-810. doi: 10.1172/JCI21318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koopman K, Uyttenboogaart M, Vroomen PCAJ, Van Der Meer J, De Keyser J, Luijckx GJ. Risk factors for cerebral venous thrombosis and deep venous thrombosis in patients aged between 15 and 50 years. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:620-622. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosenwasser RH, Weigele JB. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous and dural sinus thrombosis. Neuro-interventional Manag Diagnosis Treat 2E. 2012;18:469-484. doi: 10.3109/9781841848075.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thiansukhon E, Potigumjon A, Smitasin N. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a rare complication in cryptococcal meningitis. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;21(suppl 1):291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.03.1023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alejandra G, Carla T, Laura M. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with cryptococcal meningitis in an HIV-positive patient. J Clin Case Rep. 2014;4:421. doi: 10.4172/2165-7920.1000421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Senadim S, Alpaydin Baslo S, Tekin Güveli B, et al. A rare cause of cerebral venous thrombosis: cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:1145-1148. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2550-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kulkarni A, Kumar M, Philip VJ. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a rare complication of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV/AIDS patient. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2018;17:22-24. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ren B, Guo Y, Chen K, Chen L. An anti-human immunodeficiency virus-negative pregnant woman was diagnosed with both cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and intracranial Cryptococcus simultaneously. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2018;2:55. doi: 10.21037/jeccm.2018.05.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Equiza J, Fernandez-Eulate G, Rodriguez-Antigüedad J, et al. Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis presenting as cerebral venous thrombosis. J Neurovirol. 2020;26:289-291. doi: 10.1007/s13365-019-00813-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohamed A, Ali S, Kanyi J, Gardner A. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with recurrent cryptococcal meningitis in an HIV infected patient. J Neurol Sci. 2019;405(suppl):51. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.10.861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kammeyer J, Lehmann N. Cryptococcal fungemia leading to cerebral venous thrombosis in a multiple sclerosis patient on fingolimod. (4951). Neurology. 2020;94(15 suppl):4951 http://n.neurology.org/content/94/15_Supplement/4951.abstract [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crum-Cianflone NF, Weekes J, Bavaro M. Review: thromboses among HIV-infected patients during the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:771-778. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]