Salmonella is a zoonotic pathogen that causes gastroenteritis and other disease presentations in both humans and animals. Serovars of S. enterica commonly cause foodborne disease in Australia and globally. In 2016-2017, S. Hvittingfoss was responsible for an outbreak that resulted in 110 clinically confirmed human cases throughout Australia. The origin of the contamination that led to the outbreak was never definitively established. Here, we identify a migratory shorebird, the bar-tailed godwit, as an animal reservoir of S. Hvittingfoss. These birds were sampled in northwestern Australia during their nonbreeding period. The presence of a genetically similar S. Hvittingfoss strain circulating in a wild bird population, 2 years after the 2016-2017 outbreak and ∼1,500 km from the suspected source of the outbreak, demonstrates a potentially unidentified environmental reservoir of S. Hvittingfoss. While the birds cannot be implicated in the outbreak that occurred 2 years prior, this study does demonstrate the potential role for wild birds in the transmission of this important foodborne pathogen.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella Hvittingfoss, shorebirds, zoonotic potential, enteric pathogens, wildlife

ABSTRACT

Salmonella enterica serovar Hvittingfoss is an important foodborne serotype of Salmonella, being detected in many countries where surveillance is conducted. Outbreaks can occur, and there was a recent multistate foodborne outbreak in Australia. S. Hvittingfoss can be found in animal populations, though a definitive animal host has not been established. Six species of birds were sampled at Roebuck Bay, a designated Ramsar site in northwestern Australia, resulting in 326 cloacal swabs for bacterial culture. Among a single flock of 63 bar-tailed godwits (Limosa lapponica menzbieri) caught at Wader Spit, Roebuck Bay, in 2018, 17 (27%) were culture positive for Salmonella. All other birds were negative for Salmonella. The isolates were identified as Salmonella enterica serovar Hvittingfoss. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a close relationship between isolates collected from godwits and the S. Hvittingfoss strain responsible for a 2016 multistate foodborne outbreak originating from tainted cantaloupes (rock melons) in Australia. While it is not possible to determine how this strain of S. Hvittingfoss was introduced into the bar-tailed godwits, these findings show that wild Australian birds are capable of carrying Salmonella strains of public health importance.

IMPORTANCE Salmonella is a zoonotic pathogen that causes gastroenteritis and other disease presentations in both humans and animals. Serovars of S. enterica commonly cause foodborne disease in Australia and globally. In 2016-2017, S. Hvittingfoss was responsible for an outbreak that resulted in 110 clinically confirmed human cases throughout Australia. The origin of the contamination that led to the outbreak was never definitively established. Here, we identify a migratory shorebird, the bar-tailed godwit, as an animal reservoir of S. Hvittingfoss. These birds were sampled in northwestern Australia during their nonbreeding period. The presence of a genetically similar S. Hvittingfoss strain circulating in a wild bird population, 2 years after the 2016-2017 outbreak and ∼1,500 km from the suspected source of the outbreak, demonstrates a potentially unidentified environmental reservoir of S. Hvittingfoss. While the birds cannot be implicated in the outbreak that occurred 2 years prior, this study does demonstrate the potential role for wild birds in the transmission of this important foodborne pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonellosis is a disease caused by bacteria of the genus Salmonella and is a major public health concern worldwide (1). Salmonella is an important zoonotic pathogen that causes disease in humans and in both domestic and wild animal populations (2, 3). Globally, Salmonella spp. are estimated to cause 93.8 million cases of gastroenteritis each year (4) and are one of the most common causes of human mortality associated with foodborne disease (3). The largest burden of salmonellosis is in young children in low- and middle-income countries, with the greatest impacts in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Eastern Mediterranean (3). In Australia, an estimated 40,000 salmonellosis cases per year are attributed to contaminated food (5).

The majority of foodborne disease outbreaks are associated with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica; serovars of this subspecies are found predominantly in humans and animals and account for ∼99% of Salmonella infections in humans (2). Globally, the three serovars most commonly isolated from infections in humans are Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Salmonella enterica serovar Newport, which account for 65%, 12%, and 4% of clinical isolates, respectively (6).

Salmonella enterica serovar Hvittingfoss has caused outbreaks of salmonellosis in the United States (7) and over the past 2 decades has been responsible for several outbreaks in Australia, most recently an outbreak in 2016 caused by contaminated cantaloupes (8, 9). In Australia, S. Hvittingfoss is isolated from human, animal, and environmental sources in northern Australia (5, 10), but during outbreaks, the organism can be disseminated through the distribution of fresh produce to all states, including as far south as Tasmania (9).

Here, we report a high incidence of S. Hvittingfoss recovered from premigratory bar-tailed godwits (Limosa lapponica menzbieri) captured in Roebuck Bay, Broome, Western Australia, Australia, in March 2018. The study was a part of broader research investigating pathogenic and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in Australian shorebirds, and the high prevalence of Salmonella led to the further characterization of these isolates and the determination of their genetic relationship to other isolates.

RESULTS

A total of 326 birds were sampled (190 in 2017, 136 in 2018), representing six species of wild Australian shorebirds: ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres; n = 23), curlew sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea; n = 114), pied oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris; n = 9), bar-tailed godwit (n = 130), red-necked stint (Calidris ruficollis; n = 17), and greater sand plover (Charadrius leschenaultia; n = 33). All were screened for Salmonella spp. No individual from the 2017 expedition returned a positive Salmonella spp. culture.

All but one of the bar-tailed godwits caught in 2018 (n = 63) were caught from a single flock at Wader Spit, Roebuck Bay (−17.979327, 122.336533), on 1 March 2018. Seventeen (27%) of these birds were positive for Salmonella as determined by culture, with isolates confirmed by PCR. None of the other sampled shorebirds (n = 73) were positive for Salmonella. All 17 isolates were susceptible to the tested antibiotics. All isolates carried the aminoglycoside resistance gene aac(6’)-Iaa, which is conserved in all Salmonella organisms but not normally expressed (11). There was no significant difference in Salmonella carriage rates in the godwits based on the sex (χ2 = 1.104, df = 2, P = 0.576), weight (χ2 = 8.456, df = 8, P = 0.390), or age (χ2 = 1.036, df = 2, P = 0.596) of the bird. Serotype prediction using whole-genome sequencing analysis revealed all isolates to be S. Hvittingfoss, and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) showed that all isolates belonged to the same sequence type (ST), ST2062.

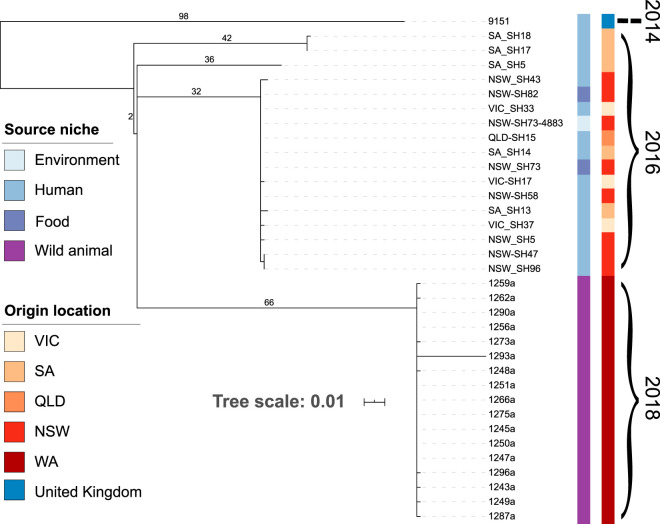

The 17 sequenced isolates were determined to be closely related via single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) comparisons, with 0 or 1 SNP between isolates for 16 of them. For isolate 1293a, there were 23 SNPs between it and all other godwit isolates; however, these SNPs were likely to be due to recombination. The isolates obtained in this study were compared to 198 publicly available S. Hvittingfoss genomes, which were from a variety of different sources of global origin (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree showing the relationship between isolates collected from bar-tailed godwits (this study) and 198 globally sourced and publicly available S. Hvittingfoss genomes on Enterobase (11). The tree was outgroup rooted with S. Paratyphi ATCC 9150 strain. Color coding of rings is based on geographic origin, source niche, and sequence type of the isolates. Australian isolates are indicated within the wild-animal section labeled “Godwits.” The tree scale represents the number of substitutions per site. The raw data for this tree can be viewed in Microreact at https://microreact.org/project/PB7XPUPsv/.

Of the 198 S. Hvittingfoss genomes that were available, 186 were uploaded to Enterobase by the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Public Health, University of Sydney. These publicly available Australian isolates were collected during the 2016 S. Hvittingfoss outbreak and formed a clade separate from all other global isolates. The genomes of isolates from the bar-tailed godwits collected in March 2018 (this study) clustered with these outbreak genomes. One non-Australian S. Hvittingfoss isolate also occupied this same genetic clade. Nevertheless, diversity was noted among the Australian S. Hvittingfoss isolates, with three different STs identified (ST434, ST446, and ST2062). No other genome sequence from an Australian S. Hvittingfoss isolate from any other year, or from any other animal, was available for comparison.

As all the bar-tailed godwit samples belonged to ST2062, a phylogenetic tree was constructed of all available ST2062 genomes. When only these isolates were examined, SNP analysis showed two distinct linages, one associated with the 2016 S. Hvittingfoss outbreak in humans and the other encompassing the 2018 godwit isolates. Sixty-eight SNPs separated the godwit isolates from the 2016 outbreaks at the nearest common ancestor (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of ST2062 S. Hvittingfoss isolates. The SNPs are noted on major branches of the tree. Color coding is based on the source niche and geographical location of each isolate. Tree scale represents number of substitutions per site.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that S. Hvittingfoss can be present in shorebirds. We detected a high prevalence of S. Hvittingfoss in bar-tailed godwits during a sampling event at a single location in northwestern Australia. These isolates were genetically similar to those causing a foodborne outbreak in humans who consumed tainted cantaloupes in 2016. While no direct link between shorebirds and foodborne outbreaks has been established in this study, the relatedness of the respective strains suggests there may be an as-yet-unknown avenue of introduction of this pathogen into the wider environment.

When the genomes of S. Hvittingfoss isolates collected from the godwits were compared pairwise, all except one genome were separated by at most a single SNP. A small amount of recombination was noted in a single isolate, resulting in a total of 23 SNPs; however, all isolates are considered clonal. This was based upon the findings of Octavia et al. (12), who determined a cutoff of four SNPs for an outbreak caused by a single strain of Salmonella spp. The close relatedness of these isolates suggests a recent colonization event in the godwits, likely from a single source.

Genetic analysis of the S. Hvittingfoss isolated from the bar-tailed godwits sampled in northwestern Australia demonstrated that the isolates were related to isolates of S. Hvittingfoss responsible for the 2016-2017 outbreak linked to contaminated cantaloupes in Australia. There were 68 SNPs relative to the most recent common ancestor. The foodborne outbreak of 2016-2017 was traced back to a single farm in the Northern Territory; however, no vector was identified that introduced S. Hvittingfoss onto the farm initially (13, 14). It is noteworthy that within the cantaloupe outbreak lineage, there is some diversity (Fig. 2). This may be due to other S. Hvittingfoss strains circulating independently of the outbreak strains during the 2016-2017 time frame, as is commonly the case in Australia and various other countries where surveillance is conducted. Nonetheless, there is a group of closely related S. Hvittingfoss strains linked to the cantaloupe outbreak, and those isolates are closely related to the godwit isolates detected in this study.

The godwit isolates clearly have a shared ancestry with the cantaloupe outbreak strains, but we are not suggesting a direct epidemiological link between wild birds and foodborne outbreaks. Rather, there is likely an unidentified common ancestor from which the 2016 and 2018 isolates descended. The S. Hvittingfoss isolates from godwits were isolated after the 2016 outbreak; thus, there is sufficient temporal and genetic difference to rule out a direct link. Despite the importance of the outbreak, the original source of the outbreak strain remains undetermined (i.e., how Salmonella got onto or into the cantaloupes) (8, 15). The presence of closely related S. Hvittingfoss in birds suggests that there may be an as-yet-unknown animal and/or environmental reservoir of this serotype.

Outside this study, the recovery of S. Hvittingfoss from wild animals has been rare. There have been only three previous reports of S. Hvittingfoss recovered from wild birds: a single species of waterfowl (two plumed whistling ducks [Dendrocygna eytoni] out of 42 birds in total) in Australia (16) and in two migrating crane species (hooded crane [Grus monacha] and white-naped crane [Antigone vipio]; nine birds out of 359) in Japan (17). Within Australia, S. Hvittingfoss has also been recovered from reptiles (two positive of 97 sampled) and feral pigs (five of 139) (16, 18, 19).

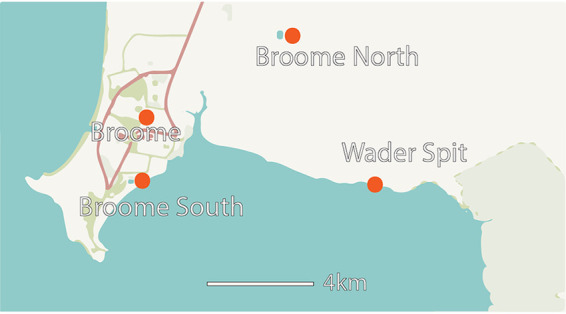

As previously mentioned, the close genetic relatedness of all isolates present in the godwits is suggestive of recent colonization from a single source. One possible source of contamination is wastewater spills that occurred in Roebuck Bay in January-February 2018. During two separate events, both the Broome South and Broome North wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) overflowed (Fig. 3). While the spills at Broome North were contained on-site, the Broome South WWTP released 39.8 million liters of treated wastewater into Roebuck Bay (20). However, there is insufficient data to state with any certainty that these wastewater spills had an impact on the Salmonella carriage in bar-tailed godwits. A direct anthropogenic transmission is unlikely, as bar-tailed godwits do not have regular human contact. They feed mainly on marine invertebrates from broad expanses of tidal mudflats in areas with low human populations (e.g., Roebuck Bay) (21).

FIG 3.

Location of the Broome North and South sewerage plants and location of the beach Wader Spit, where the flock of bar-tailed godwits was caught originally. (Adapted from OpenStreetMap.)

Salmonella infections can affect the health of avian populations, with higher mortality reported in infected birds than uninfected birds (22). Mass mortality events have been recorded due to Salmonella infections; one such event in New Zealand saw elevated mortality in many passerine (perching bird) species, from an outbreak of Salmonella Typhimurium DT160 (23). The Limosa lapponica menzbieri subspecies of the bar-tailed godwit is listed as nationally critically endangered (24) with a downward population trend. Although the birds in this study were considered healthy, there are potential negative impacts of Salmonella infection, including the possibility of salmonellosis, which could hamper conservation and population recovery.

S. Hvittingfoss is present in Australian bar-tailed godwits, suggesting that godwits, and possibly other wild birds, are able to acquire infectious agents associated with human illness. It is possible that S. Hvittingfoss was present in other shorebird species sampled in the area, but it was not detected; a contributing factor was that this study was restricted to two short sampling events across 2 years. Long-term surveillance of shorebird populations, and their environment as a whole, is needed to better understand the ecology of S. Hvittingfoss and wild bird populations (particularly godwits) and to determine the potential health threat for both wild bird populations and humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Shorebirds were captured by the Australasian Wader Study Group (AWSG) in two separate expeditions: 24 to 28 February 2017 and 23 February to 3 March 2018. These expeditions were conducted in a designated Ramsar site approximately 15 km from Broome township in the northern region of Western Australia, as part of ongoing scientific and conservation efforts involving shorebirds throughout the East Asian-Australasian flyway. Birds were captured with the aid of cannon nets, and focal species were subject to cloacal swabbing before release. Cloacal swabs were taken from these birds on specimen swabs (minitip Amies with charcoal; Copan). Transit time from sample collection to culture varied from 9 to 20 days, due to the remote nature of the fieldwork. During transit, samples were stored at ∼5°C in a portable refrigeration unit. This work was conducted under animal ethics permits issued by Federation University Australia (permit no. 16-002) and the Department of Parks and Water (permit no. 01-000179-1).

Bacterial culture, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and statistical analysis.

In the laboratory, swab tips were aseptically transferred to 5 ml of brain heart infusion broth and incubated at 35°C for 24 h for pre-enrichment. Aliquots of 100 μl were subsequently used to inoculate mannitol broth (Oxoid), azide dextrose broth (Oxoid), and selenite broth (Becton, Dickinson [BD]). All selective enrichment broths were incubated at 35°C for 18 to 48 h and then plated onto MacConkey II agar (Oxoid) or xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) agar (BD) as appropriate. All plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 to 48 h. Suspected Salmonella isolates were subcultured for purity on XLD, and preliminary testing included Gram reaction, catalase, and oxidase testing. Presumptive Salmonella isolates were confirmed by a PCR assay targeting the invA gene (25).

Confirmed Salmonella isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method (26). The antimicrobials (Oxoid) tested included ampicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20/10 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μ), imipenem (10 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (1.25/23.75 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), and colistin (10 μg). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25).

Serotyping, MLST, and phylogenetics.

DNA extraction was performed on the 17 positive Salmonella isolates, with DNA being collected from overnight colonies using a Qiagen DNeasy kit and quantified using an Invitrogen Qubit 2. The in silico serotype was inferred from whole-genome sequencing by the Microbiological Diagnostic Unit Public Health Laboratory, Doherty Institute, at the University of Melbourne. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was also conducted for the other Salmonella isolates via this service. Sequencing was conducted at the Australian Genome Research Facility using the Illumina MiSeq system, with Illumina genomic DNA shotgun library preparation with bead size selection protocol, generating 150-bp paired-end reads.

Raw sequences were uploaded to the Galaxy web platform, and data were analyzed via the public server at https://usegalaxy.org (27). Genomes were assembled using Unicycler (28), and genome assembly quality was analyzed using QUAST (29). Online services hosted by the Centre for Genetic Epidemiology were used to determine antimicrobial resistance genes (30), pathogenicity islands (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SPIFinder/), and sequence type for multilocus sequencing typing (31). Serotyping for the three sequenced isolates was determined using SeqSero (32).

Raw reads were also uploaded to Enterobase (33) for purposes of phylogenetic analysis. Phylogenetic trees were constructed in Enterobase, using their SNP Projects option. This method uses the maximum-likelihood estimation to create phylogenies. The uploaded S. Hvittingfoss isolates were compared to a data set of 183 additional publicly available whole-genome S. Hvittingfoss sequences in the database. Using the inbuilt dendrogram option, a phylogenetic tree of the genetic relationship between the 17 bar-tailed godwit isolates and all other global S. Hvittingfoss isolates was created (34). Trees were then visualized and edited in FigTree 1.4.2 (35), Microreact (36), and iTOL (37). Tree color schemes were created by Color Brewer 2.0 (38).

SNPs in the collected isolates were identified via ParSNP and visualized in Gingr (https://harvest.readthedocs.io/en/latest/content/harvest-tools.html). SNP analysis of the ST2062 subgroup was performed using the alignment matrix generated by EnteroBase’s SNP Projects in IQtree v1.6.12 (39), using a GTR (generalized time reversible) substitution model with 100 bootstrap replicates. SNPpar (https://github.com/d-j-e/SNPPar) was used to map SNPs back onto the ST2062 tree.

Data availability.

All sequences have been uploaded to NCBI. All isolates have been deposited in SRA under BioProject no. PRJNA602163. Individual S. Hvittingfoss isolate data were deposited under accession numbers SAMN13884698 (1243a), SAMN13884699 (1245b), SAMN13884700 (1247a), SAMN13884701 (1248a), SAMN13884702 (1249a), SAMN13884703 (1250a), SAMN13884704 (1251a), SAMN13884705 (1256a), SAMN13884706 (1259a), SAMN13884707 (1262a), SAMN13884708 (1266a), SAMN13884709 (1273a), SAMN13884711 (1275a), SAMN13884712 (1287a), SAMN13884713 (1290a), SAMN13884714 (1293a), and SAMN13884715 (1296a).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work would not have been possible without the generous funding provided by Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment (grant HLS-18-005) and the Stuart Leslie Bird Research Award provided by Birdlife Australia (grant FOST-18-416).

We thank the AWSG, Rosalind Jessop, and the late Clive Minton for their help with this project; assistance with permits, access to captured birds, and a deep understanding of the behavior and movements of the shorebird species in Roebuck Bay have proved invaluable. We acknowledge the Yawuru People, via the offices of Nyamba Buru Yawuru Limited, for permissions granted to AWSG to capture birds on the shores of Roebuck Bay, the traditional lands of the Yawuru people. Kathryn Holt provided helpful insight on the manuscript, and the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology–Public Health granted permission to utilize their isolates in our phylogenetic analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yan SS, Pendrak ML, Abela-Ridder B, Punderson JW, Fedorko DP, Foley SL. 2004. An overview of Salmonella typing: public health perspectives. Clin Appl Immunol 4:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cair.2003.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton PM, Nair S, Peters TM, Bale JA, Powell DG, Painset A, Tewolde R, Schaefer U, Jenkins C, Dallman TJ, de Pinna EM, Grant KA, Salmonella Whole Genome Sequencing Implementation Group. 2016. Identification of Salmonella for public health surveillance using whole genome sequencing. PeerJ 4:e1752. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR, Gibb HJ, Hald T, Lake RJ, Praet N, Bellinger DC, de Silva NR, Gargouri N, Speybroeck N, Cawthorne A, Mathers C, Stein C, Angulo FJ, Devleesschauwer B, World Health Organization Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group. 2015. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med 12:e1001923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A, Hoekstra RM, International Collaboration on Enteric Disease 'Burden of Illness' Studies. 2010. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis 50:882–889. doi: 10.1086/650733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford L, Glass K, Veitch M, Wardell R, Polkinghorne B, Dobbins T, Lal A, Kirk MD. 2016. Increasing incidence of Salmonella in Australia, 2000–2013. PLoS One 11:e0163989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eng SK, Pusparajah P, Ab Mutalib NS, Ser HL, Chan KG, Lee LH. 2015. Salmonella: a review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front Life Sci 8:284–293. doi: 10.1080/21553769.2015.1051243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh M. 2010. Salmonella lawsuit filed against Subway. Food Safety News https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2010/06/salmonella-lawsuit-filed-against-subway/.

- 8.Flynn D. 2016. How did Salmonella Hvittingfoss get on Aussie rockmelons? Food Safety News https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2016/08/130219/.

- 9.Munnoch S, Irwin M, Oxenford C, Hanson R, Owen R, Black A, Bell R. 2005. Investigation of a multi-state outbreak of Salmonella Hvittingfoss using a web-based case reporting form. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 29:379–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fearnley EJ, Lal A, Bates J, Stafford R, Kirk MD, Glass K. 2018. Salmonella source attribution in a subtropical state of Australia: capturing environmental reservoirs of infection. Epidemiol Infect 146:1903–1908. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818002224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnet S, Courvalin P, Lambert T. 1999. Activation of the cryptic aac(6′)-Iy aminoglycoside resistance gene of Salmonella by a chromosomal deletion generating a transcriptional fusion. J Bacteriol 181:6650–6655. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.21.6650-6655.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Octavia S, Wang Q, Tanaka M, Kaur S, Sintchenko V, Lan R. 2015. Delineating community outbreaks of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by use of whole-genome sequencing: insights into genomic variability within an outbreak. J Clin Microbiol 53:1063–1071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03235-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Associated Press. 2016. Rockmelon industry devastated by salmonella outbreak linked to NT farm. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/05/rockmelon-industry-devastated-by-salmonella-outbreak-linked-to-nt-farm. Accessed 15 August 2019.

- 14.Keen B. 2017. Stories from the frontline: investigating causes of salmonellosis in Australia. New South Wales Government, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claughton D, Kontominas B, Logan T. 2018. Rockmelon listeria: Rombola Family Farms named as source of outbreak. ABC Rural. https://www.hortidaily.com/article/41795/Rockmelon-listeria-Rombola-Family-Farms-named-as-source-of-outbreak/. Accessed 18 August 2019.

- 16.Hoque MA, Burgess GW, Greenhil AR, Hedlefs R, Skerratt LF. 2012. Causes of morbidity and mortality of wild aquatic birds at Billabong Sanctuary, Townsville, North Queensland, Australia. Avian Dis 56:249–256. doi: 10.1637/9863-072611-Case.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitadai N, Ninomiya N, Murase T, Obi T, Takase KJ. 2010. Salmonella isolated from the feces of migrating cranes at the Izumi Plain (2002–2008): serotype, antibiotic sensitivity and PFGE type. J Vet Med Sci 72:939–942. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iveson JB, Mackay-Scollay EM, Bamford V. 1969. Salmonella and Arizona in reptiles and man in Western Australia. J Hyg (Lond) 67:135–145. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400041516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward MP, Cowled BD, Galea F, Garner MG, Laffan SW, Marsh I, Negus K, Sarre SD, Woolnough AP. 2013. Salmonella infection in a remote, isolated wild pig population. Vet Microbiol 162:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Water Corporation. 2018. Broome high rainfall events January-February 2018: water quality sampling results report, p 1–65. Water Corporation, Osborne Park, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins PJ, Davies SJJF (ed). 1996. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds, vol 3. Snipe to pigeons. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Risely A, Klaassen M, Hoye BJ. 2018. Migratory animals feel the cost of getting sick: a meta-analysis across species. J Anim Ecol 87:301–314. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alley MR, Connolly JH, Fenwick SG, Mackereth GF, Leyland MJ, Rogers LE, Haycock M, Nicol C, Reed CE. 2002. An epidemic of salmonellosis caused by Salmonella Typhimurium DT160 in wild birds and humans in New Zealand. N Z Vet J 50:170–176. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2002.36306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birdlife Australia. 2019. Bar-tailed Godwit. http://birdlife.org.au/bird-profile/bar-tailed-godwit.

- 25.Malorny B, Hoorfar J, Bunge C, Helmuth R. 2003. Multicenter validation of the analytical accuracy of Salmonella PCR: towards an international standard. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:290–296. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.290-296.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-second informational supplement, vol. 32, p 188 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afgan E, Baker D, Batut B, van den Beek M, Bouvier D, Cech M, Chilton J, Clements D, Coraor N, Grüning BA, Guerler A, Hillman-Jackson J, Hiltemann S, Jalili V, Rasche H, Soranzo N, Goecks J, Taylor J, Nekrutenko A, Blankenberg D. 2018. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W537–W544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler GJB. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV. 2012. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang S, Yin Y, Jones MB, Zhang Z, Kaiser BL, Dinsmore BA, Fitzgerald C, Fields PI, Deng X. 2015. Salmonella serotype determination utilizing high-throughput genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 53:1685–1692. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00323-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Z, Alikhan NF, Mohamed K, Agama Study Group, Achtman M. 2019. The Enterobase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res 30:138–152. doi: 10.1101/gr.251678.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rambaut A. 2014. FigTree 1.4.2 software. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Argimón S, Abudahab K, Goater RJE, Fedosejev A, Bhai J, Glasner C, Feil EJ, Holden MTG, Yeats CA, Grundmann H, Spratt BG, Aanensen DM. 2016. Microreact: visualizing and sharing data for genomic epidemiology and phylogeography. Microb Genom 2:e000093. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Letunic I, Bork P. 2019. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res 47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brewer C. 1994. Color use guidelines for mapping and visualization, p 123–147. In MacEachren AM, Fraser Taylor DR (ed), Visualization in modern cartography, vol 2 Elsevier Science Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen L, Schmidt H, von Haeseler A, Minh B. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All sequences have been uploaded to NCBI. All isolates have been deposited in SRA under BioProject no. PRJNA602163. Individual S. Hvittingfoss isolate data were deposited under accession numbers SAMN13884698 (1243a), SAMN13884699 (1245b), SAMN13884700 (1247a), SAMN13884701 (1248a), SAMN13884702 (1249a), SAMN13884703 (1250a), SAMN13884704 (1251a), SAMN13884705 (1256a), SAMN13884706 (1259a), SAMN13884707 (1262a), SAMN13884708 (1266a), SAMN13884709 (1273a), SAMN13884711 (1275a), SAMN13884712 (1287a), SAMN13884713 (1290a), SAMN13884714 (1293a), and SAMN13884715 (1296a).