Abstract

Striated muscle contraction is the result of sarcomeres, the basic contractile unit, shortening because of hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by myosin molecular motors. In noncontracting, “relaxed” muscle, myosin still hydrolyzes ATP slowly, contributing to the muscle’s overall resting metabolic rate. Furthermore, when relaxed, myosin partition into two kinetically distinct subpopulations: a faster-hydrolyzing “relaxed” population, and a slower-hydrolyzing “super relaxed” (SRX) population. How these two myosin subpopulations are spatially arranged in the sarcomere is unclear, although it has been proposed that myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C) may stabilize the SRX state. Because MyBP-C is found only in a distinct region of the sarcomere, i.e., the C-zone, are SRX myosin similarly colocalized in the C-zone? Here, we imaged the binding lifetime and location (38-nm resolution) of single, fluorescently labeled boron-dipyrromethene-labeled ATP molecules in relaxed skeletal muscle sarcomeres from rat soleus. The lifetime distribution of fluorescent ATP-binding events was well fitted as an admixture of two subpopulations with time constants of 26 ± 2 and 146 ± 16 s, with the longer-lived population being 28 ± 4% of the total. These values agree with reported kinetics from bulk studies of skeletal muscle for the relaxed and SRX subpopulations, respectively. Subsarcomeric localization of these events revealed that SRX-nucleotide-binding events are fivefold more frequent in the C-zone (where MyBP-C exists) than in flanking regions devoid of MyBP-C. Treatment with the small molecule myosin inhibitor, mavacamten, caused no change in SRX event frequency in the C-zone but increased their frequency fivefold outside the C-zone, indicating that all myosin are in a dynamic equilibrium between the relaxed and SRX states. With SRX myosin found predominantly in the C-zone, these data suggest that MyBP-C may stabilize and possibly regulate the SRX state.

Significance

Muscle contraction is driven by sarcomere shortening and powered by myosin molecular motors that hydrolyze adenosine triphosphate (ATP). However, myosin in relaxed muscle continues to slowly hydrolyze ATP, analogous to an idling engine. Utilizing superresolution microscopy to directly image single-molecule-fluorescent ATP turnover in relaxed skeletal muscle sarcomeres, we observed two rates of myosin ATP consumption that differed fivefold. These distinct hydrolysis rates were spatially segregated, with the slower or “super relaxed” rate localized predominantly to the sarcomere C-zone. Because myosin-binding protein C, a known modulator of muscle contractile function, is found only in the C-zone, it may also serve to sequester myosin motors into the super relaxed state and thus regulate resting muscle metabolism and force generation upon activation.

Main Text

In skeletal muscle’s most basic contractile unit, the sarcomere (Fig. 1, A and B), force and motion are generated by “active” myosin molecular motors of the thick filament cyclically interacting with actin thin filaments. To power this contractile process, myosin motors hydrolyze adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Fig. 1 E), with some of the chemical energy lost as heat. Under noncontracting or “relaxed” conditions, myosin is prevented from interacting with actin because of the presence of calcium-dependent regulatory proteins on the thin filament (Fig. 1 D). Even when muscle is relaxed, the myosin motors continue to hydrolyze ATP but at a rate two to three orders of magnitude slower than during contraction (1), analogous to the consumption of fuel by an idling car. Because skeletal muscle composes ∼40% of an adult human’s mass, muscle’s energy expenditure and heat generated while relaxed are major contributors to an individual’s resting metabolic rate and thermogenesis.

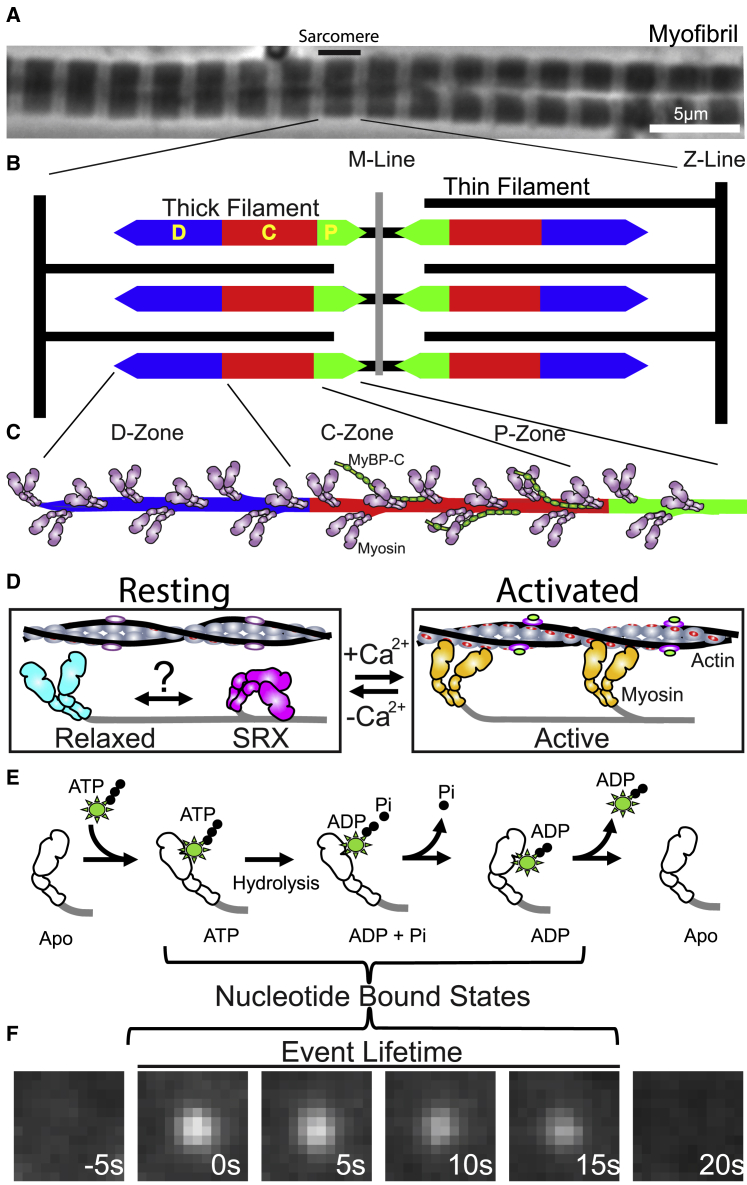

Figure 1.

Skeletal muscle myofibrils, sarcomeres, and myosin states. (A) Phase contrast image of rat soleus myofibrils with sarcomere identified. (B) Sarcomere illustration, highlighting interdigitating myosin-based thick filaments and actin-based thin filaments. Thick filaments are bipolar with the M-line at their center. Each thick filament half is described by a D-, C-, and P-zone indicated by different colors. (C) Half-thick filament illustration, with myosin motors protruding from the thick filament backbone and MyBP-C only in the C-zone. (D) In the resting condition (−Ca2+), binding sites on thin filament are blocked by troponin-tropomyosin. Myosin can adopt either a disordered “relaxed” or folded “SRX” state that are in a potential (?) dynamic equilibrium. Under activated conditions (+Ca2+), thin filament binding sites are exposed (red), and “active” myosin is free to bind actin and cause filament sliding. (E) Myosin ATP hydrolysis cycle. Upon binding a fluorescently labeled ATP, the immobilized fluorophore can be visualized as in (F). The duration of the observed fluorescence spot is a readout of the total lifetime of the nucleotide bound states. To see this figure in color, go online.

Curiously, myosin’s basal ATPase rate in the absence of actin is fivefold greater in vitro than measured in muscle fibers (2), implying an additional inhibitory mechanism must exist to lower energy usage in relaxed muscle. Thus, recent models, based on muscle fiber ATP consumption, suggest that two myosin populations exist at rest and have kinetically distinct hydrolysis rates: 1) a relaxed myosin population (Fig. 1 D), consistent with the previously described in vitro basal rate and 2) a significantly inhibited myosin population, termed “super relaxed” or “SRX” myosin (Fig. 1 D; (3)). SRX myosin may represent a “sequestered” or “off” state, which is stabilized by intramolecular interactions formed when myosin molecules in the sarcomere are packed into thick filaments (Fig. 1, C and D; (4)). Thus, the SRX state may represent a mechanism for conserving energy in relaxed muscle and for regulating force generation in active muscle through sequestration of myosin motors. Is the SRX state itself regulated? Myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C), a thick filament-associated protein localized to the sarcomere C-zone (Fig. 1, B and C; (5)), may serve this regulatory role by its proposed stabilization of myosin into the SRX state (6). If so, are SRX myosin similarly limited to the C-zone and not to flanking regions of the thick filament, which are devoid of MyBP-C (i.e., D- and P-zones; Fig. 1, B and C)? To address this question, we spatially resolved myosin’s hydrolysis of individual fluorescently labeled ATP in relaxed skeletal muscle sarcomeres, allowing us to identify the presence of SRX myosin motors and their location in the thick filament.

Myosin’s ATPase rate in the absence of actin is rate limited by the release of its hydrolysis products, inorganic phosphate (Pi), followed by the subsequent release of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (Fig. 1 E; (7)). Thus, fluorescently labeled ATP, in demembranated, relaxed skeletal muscle fibers, was used previously to monitor myosin ATPase rates, either by measuring the uptake of fluorescent ATP or the release of the hydrolysis product, fluorescent ADP (3). By this approach, the myosin SRX state was discovered (3). However, in these large muscle fibers, it was impossible to resolve the spatial location of SRX myosin motors in the sarcomere. Therefore, we isolated myofibrils from slow-twitch, rat soleus muscle. Myofibrils are contractile organelles and consist of long, repeating arrays of sarcomeres that are clearly visible as alternating light and dark bands using phase contrast microscopy (Fig. 1 A).

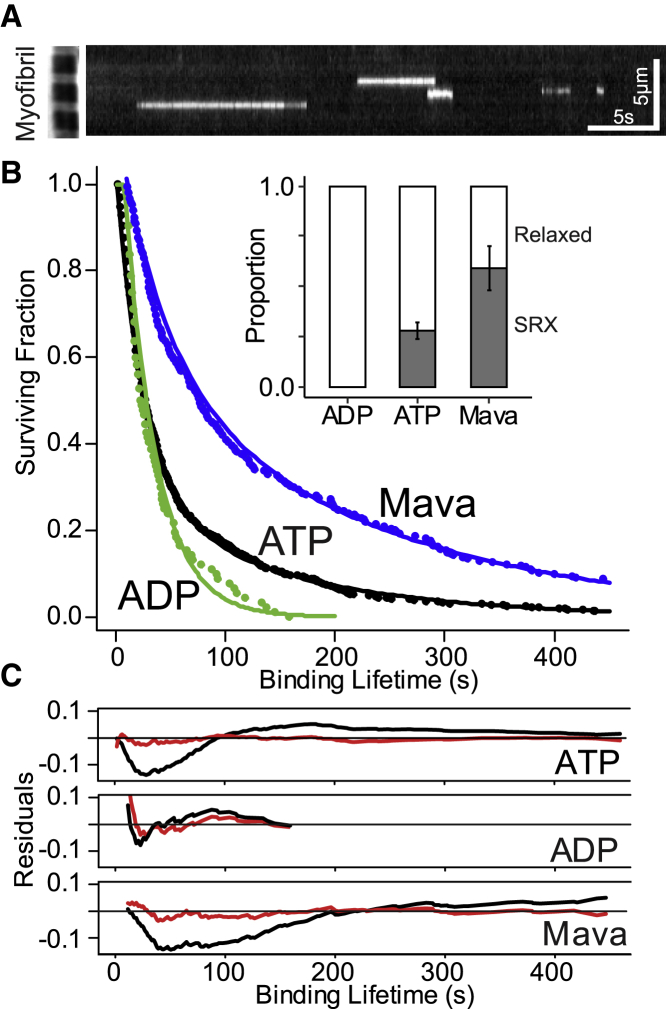

Relaxed myofibrils, adhered to a glass coverslip at room temperature (see Supporting Materials and Methods), were exposed to a limited concentration (10 nM) of fluorescent boron-dipyrromethene-labeled ATP (BODIPY-ATP) and an excess (4 mM) of nonfluorescent ATP, so that 1 out of every 400,000 ATP molecules were fluorescent. This permitted single-molecule imaging of transient fluorescent nucleotide binding in the myofibril (Fig. 1 F; Video S1). Because fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events were only seen in myofibrils in which myosin is the predominant ATPase, these events directly report the nucleotide-bound states of myosin’s ATPase cycle (Fig. 1, E and F). Specifically, appearance of a stationary BODIPY-ATP reflects its binding to myosin’s apo state, whereas the fluorescence event lifetime encompasses hydrolysis, Pi release, and ultimately the release of BODIPY-ADP (Fig. 1, E and F). As product release is rate limiting for the hydrolytic cycle, the fluorescence event lifetime (Fig. 1 F; white streaks in kymograph, Fig. 2 A) serves to estimate the myosin ATPase cycle time. The fit to the survival plot of fluorescence event lifetimes (n = 734 events from 259 sarcomeres from 20 myofibrils) was best described by the sum of two exponential populations (ATP, Fig. 2 B), as shown by reduced residuals from the fits (Fig. 2 C). The time constants differ by fivefold (i.e., 26 ± 2 and 146 ± 16 s), with the longer lifetime population accounting for 28 ± 4% of the total (inset, Fig. 2 B; Table S1). These time constants are in agreement with rabbit soleus fiber-level measurements (3), suggesting the longer lifetime population is reflective of SRX myosin.

Figure 2.

Fluorescent-nucleotide-binding lifetimes. (A) Kymograph of multiple fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events (individual streaks), with phase contrast image of a myofibril provided (left side) for scale. (B) Survival plot of fluorescent-nucleotide-binding lifetimes for myofibrils incubated in ADP (green), ATP (black), or ATP + Mavacamten (Mava) (blue). Lines are double exponential fits to each data set and inset shows relative proportions of relaxed (white) and SRX (gray) events for each experimental condition. Error bars indicate standard error for double exponential fits. (C) Residuals from fitting each experimental condition are reduced and lack clear structure when fit with double (red) versus single (black) exponential. To see this figure in color, go online.

Rat soleus myofibrils, labeled with anti-myomesin antibodies (red), incubated in Relaxing Buffer (see Materials and Methods). Transient binding of single molecules of BODIPY-ATP (green transient spots) are visible. Video is of 5 minutes of observation, playback is 30X real-time. Field of view measures 32 x 15 microns.

Upon muscle activation, SRX myosin must rapidly transition to the “relaxed” state and subsequently to the “active” state (Fig. 1 D) to generate force and motion (8). In fact, in experiments in which 4 mM unlabeled ATP was replaced with 4 mM unlabeled ADP so that myosin strong-binding was favored (9), myofibrils were unable to relax, thus preventing myosin from entering the SRX state (3). When these myofibrils were exposed to 10 nM BODIPY-ATP, myofibrils slowly contracted at 0.002 sarcomere lengths/s. Under these nonrelaxing conditions, the fluorescence event lifetimes (n = 116 events from 159 sarcomeres from six myofibrils) were best fitted by a single population with lifetimes (i.e., 25 ± 2 s) equal to the shorter lifetimes measured in relaxed myofibrils, with no evidence of SRX myosin (ADP, Fig. 2 B; Table S1). The observed kinetics suggest that the long-lived fluorescence lifetimes are sensitive to the myofibril’s activation state, as predicted for the SRX state, and not merely an artifact of nonspecific BODIPY-ATP binding. To further support the myosin-specific nature of these events, we used mavacamten: a myosin-selective, small molecule ATPase inhibitor (10) that stabilizes the myosin SRX state (11). When resting myofibrils were treated with 10 μM mavacamten, the fluorescence lifetime survival plot (n = 246 events from 328 sarcomeres from 31 myofibrils) was once again best fitted by two populations with time constants ∼50% longer than in the absence of mavacamten (Mava, Fig. 2 B). Additionally, the overall proportion of SRX events doubled from 28 ± 4 to 59 ± 11% (inset, Fig. 2 B; Table S1), confirming the SRX population originates from myosin and that mavacamten does enhance the presence of the SRX state.

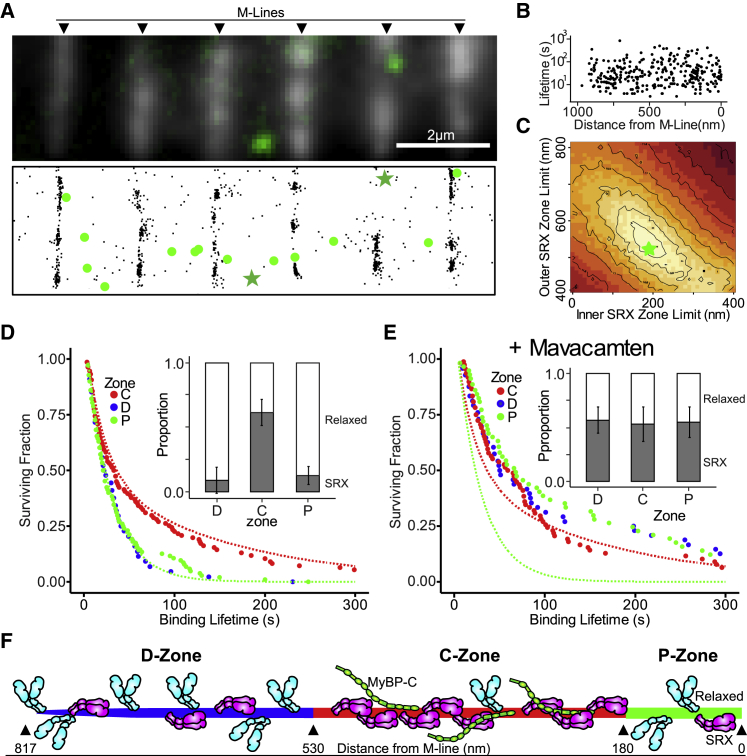

The myofibril’s well-defined structure allowed us to spatially localize SRX myosin in the sarcomere and thus determine if SRX myosins are confined to a specific location or distributed throughout the thick filament. Sarcomeres exhibit bilateral, structural symmetry about the M-line at the sarcomere center (Fig. 1 B), where myomesin, an Ig-superfamily protein, exists and connects adjacent thick filaments (12). By identifying sarcomere centers through myomesin immunofluorescence (Fig. 3 A), the center-to-center distance averaged 2.2 ± 0.2 μm, consistent with sarcomere lengths (2.3 ± 0.1 μm, N = 235 sarcomeres) measured from Z-line to Z-line in phase contrast images of myofibrils (Fig. 1 A). Then BODIPY-ATP-binding events and myomesin (M-line) were localized (Fig. 3 A) using superresolution detection algorithms (see Supporting Materials and Methods) so that the distance between each BODIPY-ATP-binding event and the M-line was measured with a combined error (σ) of 38 nm. Fluorescence binding events (n = 302 events) appeared randomly distributed up to 971 nm from the M-line (Fig. 3 B). With the distance from the M-line to the thick filament end being 817 nm (13) and allowing for localization error (σ), 97% of the BODIPY-ATP-binding events lie in the span of the myosin thick filament, providing further evidence for the myosin-specific nature of these events.

Figure 3.

Spatial localization of fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events. (A) Top panel shows fluorescence image of antimyomesin-labeled (M-line) myofibrils with an overlaid still frame showing two fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events (larger green spots). Bottom panel shows color- and drift-corrected subpixel localizations for myomesin (black points) and fluorescent-nucleotide events (green), with binding events from the upper panel denoted (green stars). (B) Scatterplot of fluorescent-nucleotide-binding event lifetimes versus distance from nearest M-line. (C) Root mean-square deviation heatmap comparing a simulated SRX-containing zone of variable width (i.e., bounded by inner and outer limits) to experimental data (see Supporting Materials and Methods). Lighter colors denote better fits, with best fit (green star; SRX Zone Limits: Inner, 180 nm; Outer, 530 nm). (D) Survival plots of binding event lifetimes localized to D-, C-, and P-zones. Dashed lines indicate theoretical curves if a zone contained only relaxed events (green) or entirety SRX events (red). Inset bar chart shows proportions of relaxed (white) and SRX (gray) events by zone. Error bars indicate standard error for double exponential fits. (E) As in (D), but for myofibrils incubated in ATP with Mavacamten. (F) Cartoon illustrating that C-zone contains the preponderance of sequestered SRX myosin (magenta, folded), whereas D- and P-zones contain predominantly relaxed myosin (cyan, extended). Distances for zones determined by modeling effort in (C). To see this figure in color, go online.

Although no spatial bias was apparent for the BODIPY-ATP-binding events (Fig. 3 B), could the long-lived SRX event population be localized to a specific sarcomeric region and thus the thick filament? To address this objectively, we developed a simple “Monte Carlo-style” model that simulated fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events along a half thick filament length (see Supporting Materials and Methods). By comparing experimental data to simulated results, a landscape emerges where the best fit to the experimental data suggests that SRX events occurred between 180 and 530 nm from the M-line (Fig. 3 C). This predicted 350 nm SRX-containing zone agrees with the C-zone location we recently reported in rat soleus fibers, based on MyBP-C immunofluorescence (13). Using this model prediction, we parsed the experimentally observed nucleotide binding events into the C-zone (180–530 nm from the M-line, n = 111) and its flanking D-zone (>530 nm from the M-line, n = 125) and P-zone (<180 nm from the M-line, n = 66), which are both devoid of MyBP-C (Fig. 3 F). We then fit fluorescence lifetime survival plots for each of these zones to double exponentials (Fig. 3 D). Based on these fits, the C-zone had 61 ± 12% SRX events, whereas the flanking D- and P-zones had 9 ± 12 and 13 ± 8% SRX, respectively (Fig. 3 D; Table S1). Thus, the SRX state appears enriched in the C-zone. However, as the slower SRX myosin population cycles through approximately fivefold less ATP in the same time as the faster “relaxed” myosin population, the SRX proportion of observed fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events (Figs. 2 B and 3, D and E), must underestimate the true SRX myosin population. Therefore, we developed a simple model (see Supporting Material) to account for this discrepancy, wherein the observed frequency of fluorescent-nucleotide-binding events is a function of both the underlying proportion of the myosin populations (relaxed or SRX), as well as the ratio of those populations’ hydrolytic rates. Using this model, we estimate that 89% of myosin in the C-zone are in the SRX state, compared to ∼40% in each of the D- and P-zones (Table S1) as illustrated in Fig. 3 F. Across the entire sarcomere, we estimate that 68% of myosin is in the SRX state, which is in close agreement with the 56% reported in prior skinned fiber studies (3).

When myofibrils were treated with 10 μM mavacamten, the proportion of SRX events doubled (Fig. 2 B; Table S1). So, where along the thick filament length did the increased SRX population originate? When BODIPY-ATP-binding events (n = 246 from 222 sarcomeres and 20 myofibrils) were spatially mapped by their distance from the M-line, the proportion of SRX events in the C-zone (53 ± 12%) was not significantly different compared to untreated myofibrils (p > 0.05, Table S1). However, the events in the D- and P-zones demonstrated a marked shift toward the SRX state (Fig. 3, D and E; Table S1). In fact, when the ATPase turnover model (see above) was used to calculate the SRX myosin population for the various zones, the D- and P-zones estimates of 88 and 87%, respectively, were nearly equal to the 86% predicted for the C-zone (Table S1), which is visually discernable by comparing the fluorescence lifetime plots in Fig. 3 D versus Fig. 3 E. Thus, the increased SRX myosin population with mavacamten was restricted to the C-zone flanking regions, confirming that myosin along the entire thick filament length can enter the SRX state. However, without pharmacologic intervention, SRX myosin state are enriched only in the C-zone, supporting MyBP-C’s putative role in stabilizing this state.

With the majority of SRX myosin motors being spatially segregated to the C-zone in resting myofibrils, what are the functional implications of this spatial segregation? In skeletal muscle, MyBP-C is believed to be a critical modulator of contractility, with its modulatory effects limited to the C-zone (13), where MyBP-C may sequester myosin into the SRX state. Interestingly, patients with skeletal MyBP-C mutations exhibit distal arthrogryposis, a condition with extreme muscle contractures (14), suggesting an impaired ability of mutant MyBP-C to sequester myosin motors into the SRX state. In fact, mutations in the cardiac isoform of MyBP-C do result in reduced proportions of SRX myosin, which may explain the hypercontractility and impaired relaxation that are characteristic of these cardiomyopathies (15,16). Therefore, focus on MyBP-C as a therapeutic target to modulate muscle metabolism and force generation is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge George Osol and Marilynn Cipolla (University of Vermont) for contribution of biological samples and insightful conversations early on with Michael Geeves and Neil Kad (University of Kent).

Funding: National Institutes of Health Grants AR067279, HL126909, and HL150953 (to D.M.W.) and supported in part by a generous gift to D.M.W. from Arnold and Mariel Goran.

Editor: Samantha Harris

Footnotes

Amy Li’s present address is Department of Pharmacy & Biomedical Sciences, La Trobe University, Bendigo, Victoria, Australia.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.036.

Author Contributions

S.R.N. methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing (original draft, review, and editing), and visualization. A.L. investigation and resources. S.B.-P. investigation and resources. G.G.K. methodology, resources, and visualization. D.M.W. conceptualization, writing (review and editing), supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. Data and materials availability: all data are available in the manuscript or the Supporting Materials and Methods. Software available upon request.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Weeds A.G., Taylor R.S. Separation of subfragment-1 isoenzymes from rabbit skeletal muscle myosin. Nature. 1975;257:54–56. doi: 10.1038/257054a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushmerick M.J., Paul R.J. Relationship between initial chemical reactions and oxidative recovery metabolism for single isometric contractions of frog sartorius at 0 degrees C. J. Physiol. 1976;254:711–727. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart M.A., Franks-Skiba K., Cooke R. Myosin ATP turnover rate is a mechanism involved in thermogenesis in resting skeletal muscle fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:430–435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909468107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alamo L., Pinto A., Padrón R. Lessons from a tarantula: new insights into myosin interacting-heads motif evolution and its implications on disease. Biophys. Rev. 2018;10:1465–1477. doi: 10.1007/s12551-017-0292-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett P., Craig R., Offer G. The ultrastructural location of C-protein, X-protein and H-protein in rabbit muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1986;7:550–567. doi: 10.1007/BF01753571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNamara J.W., Li A., Cooke R. Ablation of cardiac myosin binding protein-C disrupts the super-relaxed state of myosin in murine cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016;94:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawas R.F., Anderson R.L., Rodriguez H.M. A small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin acts on multiple stages of the myosin chemomechanical cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:16571–16577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.776815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke R. The role of the myosin ATPase activity in adaptive thermogenesis by skeletal muscle. Biophys. Rev. 2011;3:33–45. doi: 10.1007/s12551-011-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lymn R.W., Taylor E.W. Mechanism of adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis by actomyosin. Biochemistry. 1971;10:4617–4624. doi: 10.1021/bi00801a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green E.M., Wakimoto H., Seidman C.E. A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science. 2016;351:617–621. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson R.L., Trivedi D.V., Spudich J.A. Deciphering the super relaxed state of human β-cardiac myosin and the mode of action of mavacamten from myosin molecules to muscle fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E8143–E8152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809540115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eppenberger H.M., Perriard J.C., Strehler E.E. The Mr 165,000 M-protein myomesin: a specific protein of cross-striated muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1981;89:185–193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li A., Nelson S.R., Warshaw D.M. Skeletal MyBP-C isoforms tune the molecular contractility of divergent skeletal muscle systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:21882–21892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910549116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha K., Buchan J.G., Gurnett C.A. MYBPC1 mutations impair skeletal muscle function in zebrafish models of arthrogryposis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:4967–4977. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamara J.W., Li A., Dos Remedios C.G. MYBPC3 mutations are associated with a reduced super-relaxed state in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toepfer C.N., Wakimoto H., Seidman C.E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in MYBPC3 dysregulate myosin. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaat1199. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Rat soleus myofibrils, labeled with anti-myomesin antibodies (red), incubated in Relaxing Buffer (see Materials and Methods). Transient binding of single molecules of BODIPY-ATP (green transient spots) are visible. Video is of 5 minutes of observation, playback is 30X real-time. Field of view measures 32 x 15 microns.