Abstract

Upon Ca2+ influx, synaptic vesicles fuse with the presynaptic plasma membrane (PM) to release neurotransmitters. Membrane fusion is triggered by synaptotagmin-1, a transmembrane protein in the vesicle membrane (VM), but the mechanism is under debate. Synaptotagmin-1 contains a single transmembrane helix (TM) and two tandem C2 domains (C2A and C2B). This study aimed to use molecular dynamics simulations to elucidate how Ca2+-bound synaptotagmin-1, by simultaneously associating with VM and PM, brings them together for fusion. Although C2A stably associates with VM via two Ca2+-binding loops, C2B has a propensity to partially dissociate. Importantly, an acidic motif in the TM-C2A linker competes with VM for interacting with C2B, thereby flipping its orientation to face PM. Subsequently, C2B readily associates with PM via a polybasic cluster and a Ca2+-binding loop. The resulting mechanistic model for the triggering of membrane fusion by synaptotagmin-1 reconciles many experimental observations.

Significance

Ca2+-induced synchronous neurotransmitter release is essential for the integrity of neurotransmission. It was nearly three decades ago that synaptotagmin-1 was identified as the Ca2+ sensor, but despite numerous efforts, how it triggers neurotransmitter release has remained controversial. Here, molecular dynamics simulations led to a promising model that reconciles many experimental observations. A conserved acidic motif in a disordered linker, which has received scant attention, plays a key role: by competing with the vesicle membrane for interacting with the Ca2+-binding loops of the C2B domain, it flips C2B over for subsequent association with the plasma membrane. This mechanistic insight may prove useful for other synaptotagmin isoforms and extended synaptotagmins.

Introduction

At the synapse, fast synchronous release of neurotransmitters upon Ca2+ influx is essential for the integrity of neurotransmission. Neurotransmitter release results from fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic plasma membrane (PM). The fusion process is driven by the assembly of the trans-SNARE complex, comprising synaptobrevin tethered to the vesicle membrane (VM) and syntaxin and SNAP25 tethered to PM (1). However, it is synaptotagmin-1 (Syt1), a transmembrane protein in VM, that acts as the Ca2+ sensor and triggers the fusion of VM and PM (2). How Syt1 carries out this function is still hotly debated (1,3, 4, 5, 6). This study aimed to use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of full-length Syt1 (FL) associating with VM and PM to provide crucial missing information and develop a complete mechanism for the triggering of membrane fusion by Syt1.

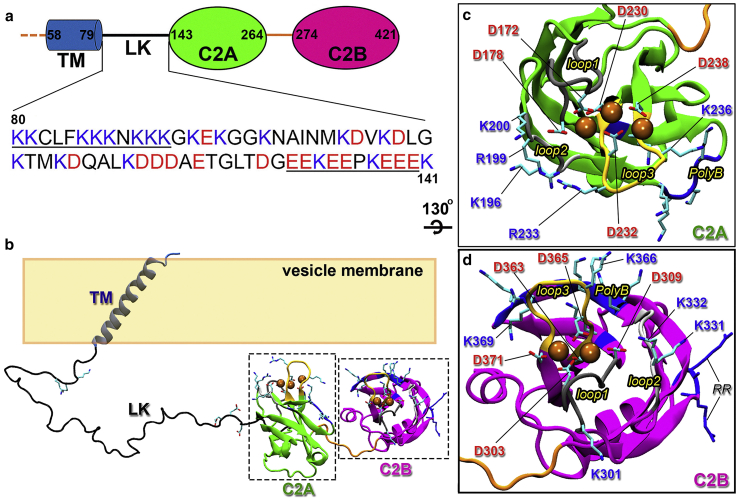

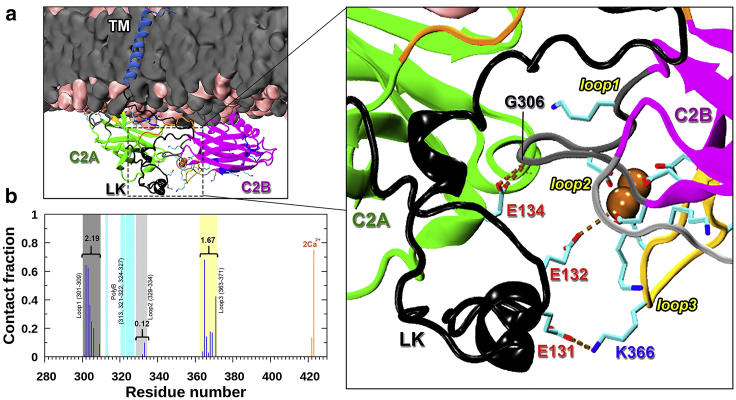

Syt1 contains an N-terminal single transmembrane helix (TM; for tethering to VM), a disordered linker (LK), and two cytoplasmic, Ca2+-binding C2 domains termed C2A and C2B (Figs. 1 a and S1). Each C2 domain folds into an eight-stranded β-sandwich, and two loops (referred to as loops 1 and 3) at the top form the Ca2+-binding site (Fig. 1, b–d; (7, 8, 9)). C2A binds three Ca2+ ions, whereas C2B binds two. Upon Ca2+ binding, these loops penetrate into acidic membranes (10, 11, 12, 13). Although phosphatidylserine (PS) is the major acidic lipid present in both VM and PM at >10% levels, the highly acidic phosphatidylinositol(4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2; Fig. S2) is also present in the inner leaflet of PM and reaches as much as 6% at the site of fusion (14,15). In addition to the Ca2+-binding loops, other sites of Syt1 have been recognized as important for binding with membranes or SNARE, including a conserved polybasic cluster (K324KKK327) on the side of C2B and a conserved RR motif (residues 398–399) at the bottom of C2B. Moreover, LK harbors a conserved TM-proximal basic motif and a conserved C2A-proximal acidic motif (Fig. 1 a).

Figure 1.

Sequence and domain structures of Syt1. (a) Syt1 domain decomposition, containing a transmembrane helix (TM), a disordered linker (LK), and two C2 domains (C2A and C2B). LK contains a basic motif and an acidic motif (underlined sequence). (b) Positioning of the domains of Ca2+-bound Syt1 relative to VM. Selected acidic and basic side chains in LK, C2A, and C2B are shown as sticks; bound Ca2+ ions are shown as spheres. (c) Enlarged view of C2A, highlighting the two Ca2+-binding loops (loops 1 and 3, with the backbone in dark gray and yellow, respectively). Aspartates coordinating Ca2+ ions and basic residues in loop 1, loop 3, loop 2 (backbone in light gray), and the polybasic cluster (backbone in blue) are shown as sticks. (d) Corresponding drawing for C2B. In addition to those with counterparts in C2A, the RR motif is shown with both the backbone and side chains in blue. To see this figure in color, go online.

The identities of the interaction partners of the foregoing sites, the relevance of these interactions to membrane fusion, and the time sequence of these interactions during fusion are a mix of consensus and controversy. Using isolated C2A and C2B domains and membranes containing either PS or PIP2 as the only acidic lipid, Bai et al. (11) obtained fluorescence intensity data to show that the Ca2+-binding loops of C2A penetrated PS-containing membranes only, whereas those of C2B penetrated PIP2-containing membranes only, implying that C2A and C2B might be specialized in binding to VM and PM, respectively. The preference of C2A for PS-containing membranes has been confirmed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (16), but supporting evidence for the preference of C2B for PIP2-containing membranes is less direct, especially in the context of FL tethered to a PS-containing membrane (17). There is evidence that the polybasic cluster of C2B contributes to its binding with PIP2-containing membranes (13,16,18, 19, 20, 21, 22). It has also been suggested that the RR motif of C2B, at the end opposite to the Ca2+-binding loops, may also bind acidic membranes (4,13,23, 24, 25). Both the polybasic cluster and RR motif have also been proposed to interact with SNARE (9,22,25,26), therefore raising the possibility that membranes and SNARE may compete for the same sites on Syt1. Wang et al. (22) have contended that the RR-PS binding is weak and is replaced by RR-SNARE binding during fusion. It should be noted that C2A also has a conserved polybasic cluster (K189KKK192; Figs. 1 c and S1; (7)), but its role has been less studied (26, 27, 28).

Based on its membrane-binding properties, different groups have proposed that Syt1 may trigger fusion by bridging VM and PM (4,13,17,20,21,23, 24, 25,28, 29, 30, 31). The bridging can be achieved with C2A bound to VM and C2B bound to PM, or with C2B simultaneously bound to VM and PM, or with C2A bound to VM while C2B bound to both VM and PM. The bridging may simply shorten the distance between the two membranes or reduce potential electrostatic repulsion between the acidic membranes or direct the final step of the assembly of the SNARE complex. Syt1 has also been proposed to bend membranes for fusion (32, 33, 34, 35). In addition, there is evidence supporting the involvement of Syt1 in the docking and priming of vesicles before Ca2+ influx (1,3,4).

Many of the fusion assays have used isolated C2 domains or the tandem C2 construct (termed C2AB). These constructs may miss crucial elements and therefore mislead mechanistic understanding (36). For example, by tethering to VM via TM, cis-binding of the C2 domains in the FL is kinetically favored over trans-binding to PM, which involves diffusion of the membranes toward each other (37). This distinction between cis- and trans-binding is lost when using the C2AB construct. Moreover, the linker between TM and C2A has been found to be important. Noting the conserved TM-proximal basic and C2A-proximal acidic motifs, Lai et al. (38) showed that charge inversion of either motif suppressed fusion. They suggested that electrostatic attraction kept the two motifs at a close distance, but a recent EPR study found that that was not the case (17). In any event, Lee and Littleton (39) found that deletion of the linker abolished synchronous neurotransmitter release, whereas duplicating the linker maintained normal function. In addition, both switching the order of the two C2 domains and tethering of Syt1 to PM also abolished synchronous release. On the computational side, electrostatic modeling and MD simulations have only been done on isolated C2 domains at membranes (21,35,40,41) or in water (42) or the C2AB construct in water (43).

Here, for the first time to our knowledge, we carried out MD simulations of FL to probe their membrane association. When tethered to VM (containing only PS as acidic lipids) by TM, C2A stably associates with VM via the two Ca2+-binding loops, but C2B has a propensity to partially dissociate. The dissociation is helped in part by the acidic motif in LK transiently interacting with the Ca2+-binding loops of C2B, thereby flipping it to potentially face PM. In comparison, C2A and C2B both stably associate with PM (containing both PIP2 and PS). When a C2B flipped from VM is placed near PM, C2B quickly associates with PM, hence bridging the space between the two membranes with C2A bound to VM and C2B bound to PM. This bridged configuration can facilitate the full assembly of the trans-SNARE complex, thereby accelerating membrane fusion.

Methods

System preparations

Two types of membranes (VM and PM) were generated using the CHARMM-GUI membrane-builder server (44). Each leaflet was composed of 400 lipids (see Fig. S2 for molecular structures of the different types of lipids used). VM was symmetric, with the following composition: 40% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS), 30% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 20% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), and 10% cholesterol. The 40% DOPS level was based on the following considerations. First, the overall PS level in the native VM was determined to be 12%; other acidic lipids were at 3% (14). Nearly all of the acidic lipids are expected to reside in the cytoplasmic leaflet (45); therefore, the level of acidic lipids that can participate in binding the cytoplasmic regions of Syt1 is ∼30% in the native VM. Second, in many experimental studies using reconstituted liposomes, the PS levels ranged from 20 to 45% (10, 11, 12, 13,21,23, 24, 25,34,37,46,47). In two previous computational studies, the PS level was even at 50% (35,41). PM was asymmetric, with the following composition for the inner leaflet: 4% PIP2, 15% DOPS, 51% DOPC, 20% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, and 10% cholesterol. For the outer leaflet, PIP2 was eliminated and made up by DOPC. The asymmetric PIP2 level is in line with reported experimental values at fusion sites (15).

The Syt1 sequence was that from rats (GenBank: NP_001028852.2), which was the one studied in many experimental works. Residues W58…C79 (corresponding to TM) was modeled as an α-helix, whereas upstream residues I53–P57 and downstream residues K80–K141 (corresponding to LK) were modeled as extended. The structure of C2AB was from PDB: 5KJ7 (chain E; residues K141–A418) (48) but with three Ca2+ ions bound to C2A based on superposition to PDB: 1BYN (8). TM was inserted into VM manually in VMD (49), and clashed lipids were removed.

MD simulations

Amber ff14SB (50), Lipid17 (51), and TIP4PD (52) (https://github.com/ajoshpratt/amber16-tip4pd) were used for modeling the proteins, lipids, and water, respectively. Lipid17 did not have parameters for PIP2, which we produced using the general Amber force field (GAFF) (53). Specifically, GAFF supplied all parameters except for atomic charges, which we obtained by restrained fitting to the quantum mechanical (Gaussian 16 at the HF/6–31G∗ level) electrostatic potential (Fig. S3). For LK in solution, the simulation box had dimensions of 100 × 100 × 70 Å (3), allowing at least 12 Å of solvent between the solute and the nearest box boundary. For the LK and FLΔC2AB at VM, the box dimensions were 172 × 172 × 160 Å (3); for FLΔC2B and FL, the dimensions were increased to 172 × 172 × 200 Å (3). The box dimensions for C2AB at PM were similar at 173 × 173 × 190 Å (3). All the systems were neutralized by replacing water with K+ and Cl−, and the final KCl concentration was 150 mM. The solvation was done using the leap module of AMBER17 tools.

The systems were equilibrated in NAMD (54). For those containing either VM or PM, a CHARMM-GUI-recommended protocol (44) was largely followed. After 10,000 cycles of energy minimization, each system was simulated at constant NVT with a timestep of 1 fs for 50 ps with the protein and lipid headgroups restrained (the strength of lipid restraints was reduced to half in the second half of the simulation). Subsequently, the simulation switched to constant NPT, initially (for 25 ps) with the lipid restraints further reduced by half but thereafter (for 600 ps) with the lipid restraints removed all together, and the timestep increased to 2 fs. All the while, the protein restraints were gradually reduced. The system was last equilibrated at constant NPT for 8 ns without any restraint.

Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated by the particle mesh Ewald method (55), with nonbonded cutoff at 12 Å. All bonds connected to hydrogens were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm (56). The temperature was maintained at 303 K using the Langevin thermostat with a damping coefficient of 1 ps−1, and the pressure was maintained at 1 atm using the Langevin piston method (57).

The simulations for all the VM systems (and for LK in solution) were continued using pmemd.cuda on GPUs (58). For each system, four replicate runs were generated with different random seeds, and after a 200-ns equilibration period, the production period of each run was 1000 ns. For the PM system, two replicate production runs were collected in NAMD, each for 500 ns.

For C2AB in the presence of both VM and PM, the system was prepared by taking C2AB and VM from a snapshot in the FL-VM simulations (at 222 ns of sim1) and PM from the C2AB-PM simulations. The two membranes were trimmed down to ∼280 lipids per leaflet. The separation between them was selected by trial and error in short simulations to approximate the 50-Å-value determined by Lin et al. (31) when Syt1 was associated with the two membranes. In the final selected setup, the inner phosphate planes of VM and PM were separated by 60.6 Å, water and ions within 3.5 Å of the protein and lipids were removed, and the dimensions of the simulation box were 140 × 160 × 218 Å (3). The voids left by the solvent removal around the protein would lead to contraction of the inner solvent chamber. The system was energy minimized for 5000 cycles and equilibrated at constant NVT for 50 ps and constant NPT for 50 ps with a timestep of 1 fs, the first half with both the protein and lipids fixed and the second half with them free. In the second half, the intermembrane separation gradually reduced to 52.6 Å as the inner solvent chamber contracted. The production run then continued with a timestep of 2 fs at constant NPT for 700 ns, during which the VM-PM separation settled around 50.3 Å, nearly identical to the experimental value of Lin et al. Four additional simulations were carried out, with the production run for each accumulating 259 ns.

Trajectory analyses

MD trajectories were analyzed using CPPTRAJ (59) and the VMD tcl scripts (49). Snapshots at 1-ns intervals were analyzed. A contact was defined as formed when the distance between any heavy atom of a residue was within 3.5 Å of any heavy atom of a membrane or the linker acidic motif. For each snapshot, the total number of residues in a C2 domain that formed contacts with a membrane (or the linker) is termed the contact number. A C2 domain was considered to be associated with a membrane (or the linker) if the contact number was ≥1; otherwise, they were said to be dissociated from each other. For each residue, the membrane contact fraction was calculated as the ratio between the number of snapshots in which the residue was in contact with the membrane and the total number of snapshots analyzed. For linker-C2B interactions, however, the contact fraction of a residue was calculation among the snapshots in which C2B was associated with the linker. For some motifs (e.g., loop 3), we also report the sum of the contact fractions of the constituent residues.

For a residue that was in frequent contact with a membrane, we recorded the time series of its contact state in each trajectory as a binary number (1 for being in membrane contact and 0 for not in contact). The lifetimes of the membrane contact, as indicated by the length of a contiguous stretch of 1s (with minimal length set to 2), were averaged and reported as the mean lifetime. Lifetimes were not calculated for residues that less frequently contacted the membrane because of poorer statistics.

Hydrogen bonds were defined as formed when the donor-acceptor distance was less than 3.5 Å and the donor-hydrogen-acceptor angle was greater than 135°. Hydrogen bonds were collected between nitrogen and oxygen atoms of a residue (both side chain and backbone) as donors and oxygen atoms of phospholipids as acceptors. The buried surface area was calculated by subtracting the solvent accessible surface area of the complex between a C2 domain and a membrane from the sum of the surface areas of the domain and the membrane.

To assess sampling convergence over simulation time, we calculated the mean values of a property (e.g., contact number or distance between two groups of atoms) over two segments of a trajectory, 200–600 and 600–1000 ns. For each time segment, the set of four mean values of the replicate simulations was treated as a sample, and a two-sample t-test was conducted to see whether the difference in mean value between the two time segments was statistically significant (at 95% confidence level). If not, then we concluded that convergence was reached over simulation time.

Results

We carried out MD simulations of FL (actually, residues 53–418 without the lumenal N-terminus and missing the C-terminal three residues) as well as several shorter constructs: LK (residues 80–141), FL with the C2 domains truncated (FLΔC2AB; residues 53–141), FL with C2B truncated (FLΔC2B; residues 53–264), and the two tandem C2 domains (C2AB; residues 143–418). These constructs were tethered to or at VM (composition: PS/PC/PE/cholesterol = 40:30:20:10), PM (PIP2/PS/PC/PE/cholesterol = 4:15:51:20:10 for inner leaflet), or both. We ran four replicate simulations (referred to as sim1 to sim4), each 1 μs long, for constructs (FL, FLΔC2B, FLΔC2AB, and LK) interacting with VM only; two replicate simulations, each 0.5 μs long, for a construct (C2AB) interacting with PM only; and five simulations (one for 0.7 μs and four for 259 ns each) for C2AB interacting with both VM and PM.

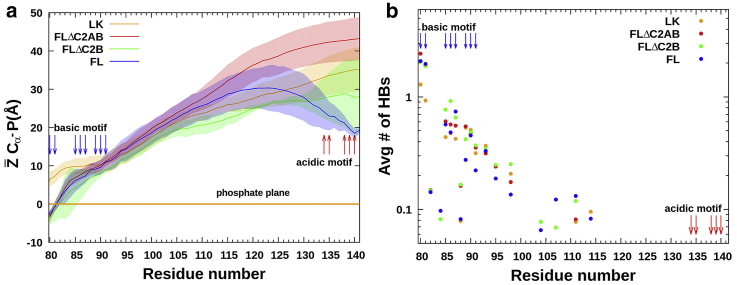

The linker has minimal VM association and self-interaction

We first probed the extent to which LK associates with VM when Syt1 is tethered to this membrane via TM. According to the average distances () of Cα atoms from the plane of lipid phosphate atoms (Fig. 2 a), only the very TM-proximal lysines are frequently in contact with VM. At the neutral residue N88, the linker starts to peel off from the membrane. This pattern for the first half of the linker holds regardless of the sequence truncations beyond the linker. Indeed, it remains true even for the isolated linker, except for the somewhat larger -values for the first two lysines because of the lack of TM tethering. For most of the simulation time, the other end of the linker does not come into contact with VM because of electrostatic repulsion by the acidic motif (Videos S1 and S2). However, -values do progressively reduce as the constructs get longer because of VM association of the C2 domains (see below). In line with the results, the average number of hydrogen bonds per residue with VM is high (>0.5) for the first five lysines but decays rapidly after N88, with only occasional hydrogen bonds formed by lysines in the middle of the linker sequence (Fig. 2 b). These results agree well with recent EPR data of Nyenhuis et al. (17), showing that a spin label attached to residue 86 is in contact with lipids but those beyond (at 90, 95, 123, and 136) are in aqueous environments.

Figure 2.

VM association of LK. (a) Z̄Cα-P, the average distance of each Cα atom from the phosphate plane. Shaded bands represent standard deviations among four replicate simulations. (b) The average number of hydrogen bonds between a linker residue and lipids. The lysines and glutamates near the linker termini are indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

Lai et al. (38) suggested that the basic and acidic motifs attract each other to compact the linker, but EPR data of Nyenhuis et al. showed that these motifs, at most, form transient interactions. Our MD simulations are consistent with the EPR data. For LK in solution, the basic and acidic motifs do frequently come into contact (Video S3); the distances between the centers of geometry of K85KKNKKK91 and E134EPKEEE140 average at 27 Å (Fig. S4). Near VM, the contact between the basic and acidic motifs becomes much less frequent for LK, with the average distance between them increasing to 46 Å because the basic motif is now engaged with VM and the acidic motif is repelled by acidic lipids (Video S1). When tethered to VM via TM, any contact between the basic and acidic motifs is very transient, and their average distance further increases to around 65 Å (Video S2).

C2A, but not C2B, stably associates with VM

In our FL-VM simulations, C2A stably associates with the membrane (Fig. 3 a), with the membrane contact number, i.e., the number of residues in contact with lipids, averaging around 12 (Fig. S5 a). In contrast, C2B on average has only about half the membrane contact number and sometimes dissociates from the membrane altogether (Fig. S6 a). This contrast between C2A and C2B is also shown by the buried surface area (Figs. S5 b and S6 b) and the number of hydrogen bonds formed with VM (Figs. S5 c and S6 c).

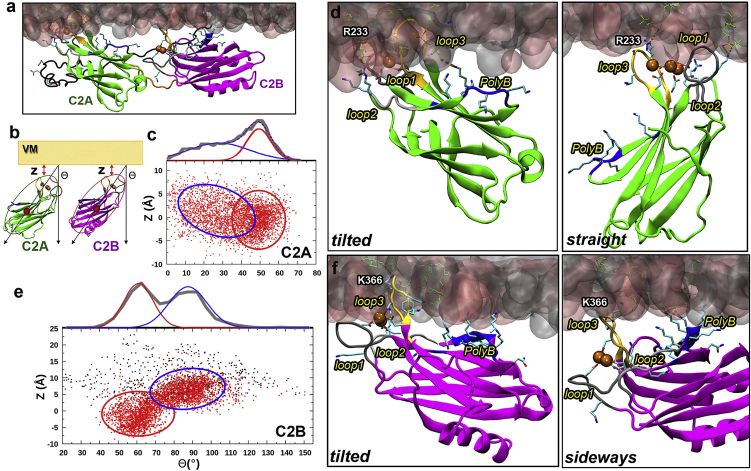

Figure 3.

VM-associated configurations of C2A and C2B in FL simulations. (a) A snapshot from the FL-VM simulations. (b) Illustration of the smallest displacement (Z) of any Cα atom in a C2 domain from the phosphate plane and the tilt angle (Θ) of the domain. (c) Scatter plot of C2A Θ and Z collected from the simulations. The red and blue ovals indicate ensembles in the tilted and straight poses, respectively. The histogram in Θ was fitted to a sum of two Gaussians, corresponding to the two types of poses. (d) Left: enlarged view of C2A in the tilted pose shown in (a). Right: C2A in the straight pose from a different snapshot. R233 in loop 3 is labeled. (e) Scatter plot of C2B Θ and Z. Red and black dots represent VM-associated and -dissociated snapshots, respectively; red and blue ovals indicate ensembles in the tilted and sideways poses, respectively, of VM-associated C2B. The Θ histogram of VM-associated C2B was fitted to a sum of two Gaussians. (f) Right: enlarged view of C2B in the sideways pose shown in (a). Left: C2B in the tilted pose from a different snapshot. K366 in loop 3 is labeled. To see this figure in color, go online.

We defined two parameters to characterize the position and orientation of each C2 domain relative to VM: the smallest displacement (Z) of any Cα atom in the domain from the phosphate plane and the angle (Θ) between the membrane normal and the vector from the Ca2+ ions to the center of the domain (Fig. 3 b). The angle-displacement scatter plot of C2A shows two overlapping ensembles, one around Θ = 50° and Z = −0.5 Å and the other around Θ = 25° and Z = 2 Å (indicated by ovals and a fit of the Θ-histogram to a sum of two Gaussians; Fig. 3 c), which will be called “tilted” and “straight,” respectively (Fig. S7, a and b). In the simulations, C2A readily transitions between the straight and tilted poses (Fig. S5 d). In the straight pose (approximately half of all snapshots, estimated from the areas under the two Gaussians), VM association of C2A is stabilized by contacts with lipids by the three loops at the top; in the tilted pose, the polybasic cluster, in which we now include K182, participates in interacting with lipids, and meanwhile, loop 1 becomes somewhat less important (Fig. 3 d). The VM contact numbers of C2A are approximately the same in the straight and tilted poses (Fig. S5 a). Overall, the three loops and the polybasic cluster of C2A provide nearly all the stabilization of VM association (Fig. 4 a).

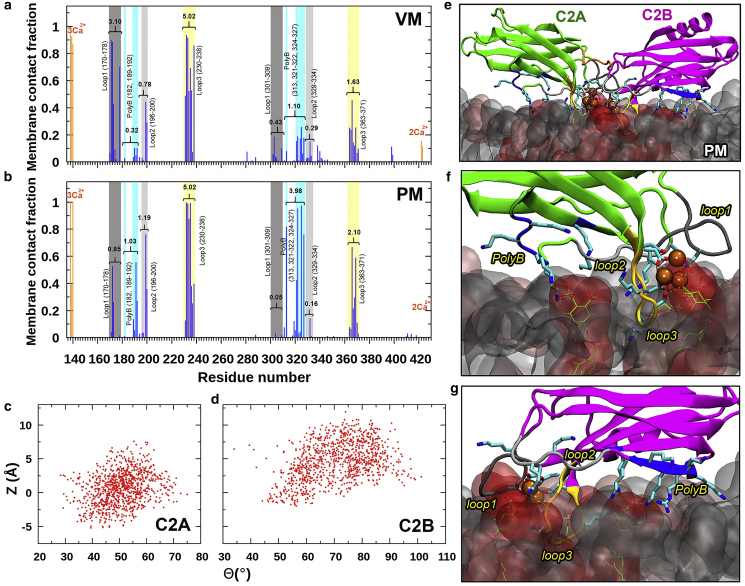

Figure 4.

Comparison of VM and PM association of C2AB. (a) Fractions of snapshots in which individual C2AB residues form membrane contacts in the FL-VM simulations. The sums of membrane contact fractions of residues in some motifs (e.g., loop 3) are indicated. (b) Counterparts for the C2AB-PM simulations. (c) Scatter plot of C2A Θ and Z collected from the C2AB-PM simulations. (d) Scatter plot of C2B Θ and Z. (e) A snapshot from the C2AB-PM simulations. (f) Enlarged view of C2A showing PM interactions. (g) Enlarged view of C2B. To see this figure in color, go online.

In the dissociated snapshots of C2B (13.5% of total), Θ and Z are randomly scattered over wide ranges (21–148° in Θ and 2.0–24.0 Å in Z; Fig. 3 e); below, we will revisit C2B partial dissociation from VM. On the other hand, the VM-associated snapshots form two dense ensembles, one centered around Θ = 60° and Z = −2 Å and the other around Θ = 90° and Z = 6 Å. We refer to these two types of poses as tilted and sideways (Fig. S7, c and d). In the tilted pose (approximately half of the snapshots with VM contacts), loop 3 of C2B penetrates inside the phosphate plane, and there are opportunities for VM engagement by loops 1 and 2 and especially by the polybasic cluster, which we now widen to include K313, K321, and R322 (Fig. 3 f, left panel). In the sideways pose, mostly it is the polybasic cluster, followed by loop 3, that interacts with lipids (Fig. 3 f, right panel), but the membrane association is not very stable, and C2B tends to roll on its side. Consequently, other residues, including R281, K288, Y338, N340, and the RR motif (see below), also participate in lipid interactions occasionally. The VM contact number of C2B in the sideway pose is less than that in the tilted pose (averaging 3 and 8, respectively; Fig. S6 a). Overall, loop 3 and the polybasic cluster make the dominant contributions to C2B-VM association (Fig. 4 a).

The contrast in VM-association stability between C2A and C2B can be illustrated by the four residues in each C2 domain with the highest membrane contact fractions (i.e., a fraction of snapshots in which a given residue is in membrane contact; Fig. 4 a). For C2A, the top four comprises loop 1 residues Leu171–Asp172 and loop 3 residues Asp232–Arg233. Their membrane contact fractions average to 0.91, and their mean lifetimes range from 22 to 44 ns. In comparison, the top four for C2B comprises polybasic residue Lys325 and loop 3 residues Tyr364, Lys366, and Lys369. Their membrane contact fractions average only to 0.31, and their mean lifetimes are only 4–7 ns. Note that the contrast in VM contact between C2A and C2B did not arise from any bias in the initial setups, in which neither C2A nor C2B formed many VM contacts (Fig. S8, a and b). Rather, the contact number of C2A grew significantly during a 200-ns equilibration period, whereas that of C2B stayed relatively low, and this difference persisted in the subsequent 1000-ns production period (Figs. S5 a and S6 a). To further confirm that the difference in VM contact is intrinsic to the C2 domains, we started a fresh set of replicate simulations, starting from a snapshot in the previous FL-VM simulations, in which C2B had a greater contact number than C2A (15 vs. 11). Within 10 ns, the contact number of C2B reduced to its typical low value of around 6, whereas that of C2A remained at a high level around 12 (Fig. S8, d and e).

The more stable VM association of C2A relative to C2B seen in our MD simulations is supported by several experimental studies. Using isolated C2 domains (Ca2+ bound), Hui et al. (46) found that C2A complexes with PS membranes were much stronger than C2B complexes. The same study also found that a KAKA mutation, i.e., mutation of K326 and K327 in C2B to alanine, significantly weakened C2B-PS binding. Li et al. (19) likewise obtained a destabilizing effect for the KAKA mutation on C2AB-PS binding, and an even greater effect for mutating R233 in C2A loop 3 to glutamine, but a minimal effect for a corresponding mutation of the C2B loop 3 residue K366. The destabilizing effect of the KAKA mutation is in line with the significant involvement of the polybasic cluster of C2B in VM association in our simulations (Figs. 3 f and 4 a). The greater destabilization of the R233Q mutation validates our simulation result that loop 3 of C2A contributes the highest sum of VM contact fractions among all the motifs that potentially interact with VM (Fig. 4 a). Lastly, the contrasting effects of the R233Q and K366Q mutations provide direct confirmation of the different extents of VM engagement by the loop 3s of the two C2 domains in our simulations. Like its counterpart in C2A, loop 3 in C2B also contributes the highest sum of VM contact fractions within C2B, but the C2B sum is three times lower (5.02 for C2A vs. 1.63 for C2B). Of the two residues mutated by Li et al., R233 is the second most frequent VM-contacting residue in C2A (barely exceeded by the neighboring Ca2+-coordinating D232) (Figs. 3 d and 4 a), whereas K366 is the runaway number one VM-contacting residue in C2B (Figs. 3 f and 4 a). Still, R233 is two times more likely to contact VM than K366.

In contrast to the stable VM association of C2A in FL, upon deletion of C2B, C2A has a tendency to dissociate from VM (Fig. S9 a). Note that C2A was in exactly the same configuration in the initial setups of the FL-VM and FLΔC2B-VM systems, and the difference in VM contact for C2A developed in the 200-ns equilibration period (Fig. S8, a and c). In the production period of the FLΔC2B-VM system, dissociation of C2A occurs in 36% of all snapshots. In the nondissociated snapshots, ∼80% are in the tilted pose, and the other 20% are in the sideways pose (Fig. S9, b and c). Therefore, the presence of a C2B that is not even stably associated with VM can still strengthen the association of C2A with VM. This stabilization also has direct experimental support. For example, Hui et al. (46) found that the C2AB construct bound to PS membranes much more strongly than the isolated C2A domain. C2B provided stabilization even when its PS binding ability was reduced by loop 3 mutations that interfered with Ca2+ binding, although the extent of stabilization was commensurately reduced. Likewise, EPR data of Herrick et al. (12) suggested that C2AB positioned more deeply into PS membranes than the isolated C2A domain. Lastly, kinetic measurements of Tran et al. (47) showed that C2AB dissociated from PS membranes much more slowly than the isolated C2A domain. The stabilization provided by C2B can be rationalized theoretically as a linkage effect, which results in an increase in the effective concentration of C2A (60).

C2B stably associates with PM because of polybasic cluster-PIP2 interactions

Our C2AB-PM simulations show that both C2A and C2B stably associate with PM (Figs. 4, b–g, S8, f and g, and S10). PM-associated C2A adopts an orientation very similar to the tilted pose of VM-associated C2A (compare Fig. 3 c, region outlined by a red oval, and Fig. 4 c; also compare Fig. 3 d, left panel, and Fig. 4 f). Meanwhile, the tilt of PM-associated C2B moves toward a sideways orientation but without the rolling of VM-associated C2B (compare Figs. 3 e and 4 d; also compare Figs. 3 f and 4 g). This stable sideways pose comes from a much greater participation of the polybasic cluster in interacting with PM (Fig. 4 b compared with Fig. 4 a), which is directly supported by EPR data of Kuo et al. (13) PM interactions of C2B are overwhelmingly with PIP2 (Fig. 4 g).

Although C2A stably associates with PM in the C2AB construct, it should be recognized that, in the context of FL that is tethered to VM via TM, C2A association with VM is favored over PM both kinetically (37) and thermodynamically (60) because of the TM-C2A linkage. Indeed, recent EPR data of Nyenhuis et al. (17) demonstrated that C2A in FL preferentially associated in cis with PS-containing membranes even when PIP2-contaning membranes were present in trans.

Interactions with linker acidic motif stabilize C2B when partially dissociated from VM

We more closely investigated why C2B in FL would partially dissociate from VM. The snapshot at 218 ns in sim1 in which C2B has the largest tilt angle of 150.4° (Video S1. LK-VM Simulation, Video S2. FLΔC2AB-VM Simulation, Video S3. Simulation of an LK in Solution, Video S4. A Segment of an FL-VM Simulation, Video S5. Simulation of C2AB Associating with Both the VM and PM), meaning that this domain is flipped to have its bottom facing VM, caught our attention. In this snapshot, the Ca2+-binding loops at the top face the acidic motif of the TM-C2A linker, whereas the RR motif at the bottom interacts with VM (Fig. S6 e). We therefore looked for interactions between the acidic motif and the Ca2+-binding loops of C2B and found that they started to make contact at 152 ns. Fig. 5 a presents their interactions at 193 ns of sim1. A video showing the simulation from 150 to 225 ns (Video S4) gives the appearance that the contact with the acidic motif tips over C2B.

Figure 5.

Interactions of the linker acidic motif with C2B Ca2+-binding loops. (a) Snapshot at 193 ns of FL-VM sim1. Shown on the right is an enlarged view that illustrates the interactions of Glu131, Glu132, and Glu134 interacting with loops 1 and 3 and a Ca2+ ion in C2B. (b) The fractions of snapshots in which individual C2B residues form contacts with acidic residues in the linker, among all snapshots in which at least one such contact is formed. To see this figure in color, go online.

Contact of C2B with the acidic motif is actually quite prevalent, occurring in 10% of all snapshots in the FL-VM simulations (Fig. S11). Nearly all the interactions of the acidic motif are with loops 1 and 3 of C2B (Fig. 5 b). There is little chance for the acidic motif to interact with the polybasic cluster, in line with the EPR data of Nyenhuis et al. (17) Thus, it seems that the acidic motif of the TM-C2A linker competes with VM for C2B interaction, stabilizing C2B when it is partially dissociated from VM. The RR motif of C2B may also play a minor role by interacting with VM.

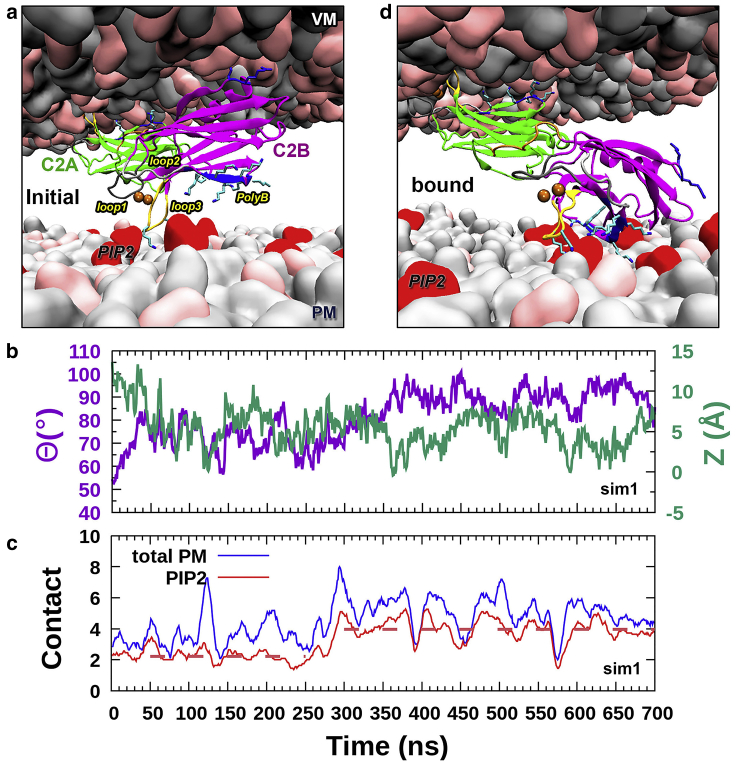

C2B released from VM readily associates with PM

To fully mimic the physiological situation of membrane fusion, we placed PM next to a C2B that was partially dissociated from VM (Fig. 6 a; see Video S5 for the simulation). The simulation started with C2B flipped to face PM. Although C2A remains stably associated with VM (Fig. S12 a, left panel), C2B quickly (within ∼50 ns) approaches PM, and its tilt moves toward a sideways orientation (Fig. 6 b; compare with C2B tilt angles in the C2AB-PM simulations shown in Fig. 4 d). Around 290 ns, more PIP2 molecules come near C2B (Fig. S12 b, left panel), and C2B responds by further increasing its tilt angle (Fig. 6 b) to form more interactions between the polybasic cluster and PIP2, thereby driving up the total number of membrane contacts (Fig. 6 c). From 350 ns onward, C2B is stably associated with PM (Figs. 6 d and S12 c). These observations are all reproduced in four additional simulations (Figs. S12, a and b and S13).

Figure 6.

PM association of C2B released from VM. (a) An initial snapshot in which C2B released from VM is placed near PM. (b) Time traces of C2B Θ and Z. (c) Time trace of C2B contacts with PIP2 molecules or with all PM lipids; each trace is smoothed using the running average in a 11-ns window. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the average C2B-PIP2 contact numbers from 50 to 250 ns and from 300 to 700 ns. (d) A snapshot in which C2B becomes stably associated with PM, showing the polybasic cluster and loop 3 (side chains shown as sticks) interacting with PIP2 molecules (shown as the red surface). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Through extensive MD simulations of FL and several shorter constructs at both VM and PM, we have gained unprecedented information and insight on the membrane association and conformational transition that are likely to be relevant for the triggering of membrane fusion by Syt1. When associated with either VM or PM, Syt1 is highly dynamic, with distinct poses (e.g., tilted and straight for C2A) and each comprising a broad ensemble of configurations, and sometimes C2B even dissociates from VM. Given this dynamic nature, MD simulations are uniquely able to characterize the biophysical properties of the Syt1-membrane system. Still, our simulation results are directly supported by multiple experimental studies, including those reporting EPR data, membrane-binding assays, and kinetic measurements.

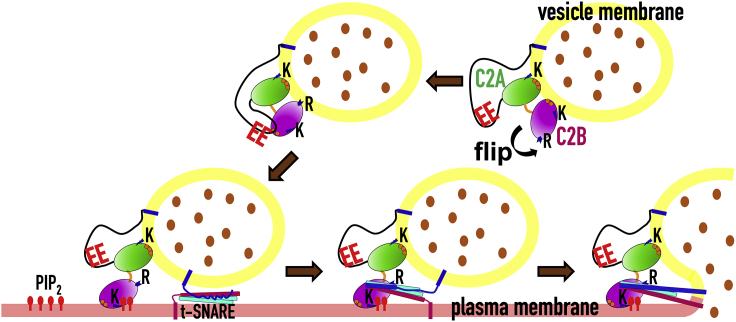

The most interesting finding from the MD simulations is that the conserved acidic motif in the TM-C2A linker can compete with VM for interacting with the Ca2+-binding loops of C2B, thereby flipping its orientation toward PM (Fig. 7, top row). A speculation that the acidic motif may help compact the linker by interacting with the upstream basic motif (38) turned out to be inconsistent with subsequent EPR data (17). Nevertheless charge inversion of the acidic motif suppressed membrane fusion (38). Moreover, deletion of the linker abolished synchronous neurotransmitter release, whereas duplicating the linker had no effect (39). These observations support the importance of the acidic motif, and interactions with the Ca2+-binding loops of C2B can explain this importance.

Figure 7.

For a Figure360 author presentation of this figure, see https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.008.

Proposed model for the triggering of membrane fusion by Syt1. By interacting with the Ca2+-binding loops, the linker acidic motif flips C2B from VM-facing to PM-facing. C2B then quickly associates with PM, providing a platform for the complete assembly of the trans-SNARE complex. To see this figure in color, go online.

Our simulations further showed that, when flipped from VM, C2B quickly associates with PM (Fig. 7, bottom row). Syt1 now bridges the space between the two membranes, with C2A bound to VM and C2B bound to PM. In this bridged configuration, C2B, especially through its RR motif (9), presents a platform for the trans-SNARE complex to complete its assembly. Membrane fusion then finally ensues. Our bridging model, in contrast to those relying on C2B simultaneously binding to both VM and PM, explains why it is important to preserve the order of C2A followed by C2B along the amino acid sequence and to tether Syt1 to VM, as both switching the order of the two C2 domains and tethering of Syt1 to PM abolished synchronous release of neurotransmitters (39).

Although this work has focused on Ca2+-bound Syt1, it will be interesting to apply MD simulations to characterize the interactions of Syt1 before Ca2+ influx. Likewise, it would be fruitful to compare and contrast Syt1, the primary Ca2+ sensor in synchronous neurotransmitter release, with other synaptotagmin isoforms, such as Syt7 (41,47), which plays a prominent role in asynchronous neurotransmitter release (61). Lastly, MD simulations such as those presented here can also help to understand the lipid transport mechanisms of extended synaptotagmins, which are tethered to the endoplasmic reticulum and associate with PM via C2 domains (62).

Author Contributions

H.-X.Z. and R.P. designed the research. R.P. performed the research and analyzed the data. H.-X.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alan Hicks for technical help.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM118091.

Editor: Michael Grabe.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.008.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Jahn R., Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brose N., Petrenko A.G., Jahn R. Synaptotagmin: a calcium sensor on the synaptic vesicle surface. Science. 1992;256:1021–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1589771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunger A.T., Choi U.B., Zhou Q. Molecular mechanisms of fast neurotransmitter release. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018;47:469–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-034117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S., Trimbuch T., Rosenmund C. Synaptotagmin-1 drives synchronous Ca 2+-triggered fusion by C 2 B-domain-mediated synaptic-vesicle-membrane attachment. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:33–40. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park Y., Ryu J.-K. Models of synaptotagmin-1 to trigger Ca 2+ -dependent vesicle fusion. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:3480–3492. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowers M.R., Reist N.E. Synaptotagmin: mechanisms of an electrostatic switch. Neurosci. Lett. 2020;722:134834. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.134834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton R.B., Davletov B.A., Sprang S.R. Structure of the first C2 domain of synaptotagmin I: a novel Ca2+/phospholipid-binding fold. Cell. 1995;80:929–938. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao X., Fernandez I., Rizo J. Solution structures of the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound C2A domain of synaptotagmin I: does Ca2+ induce a conformational change? Biochemistry. 1998;37:16106–16115. doi: 10.1021/bi981789h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Q., Lai Y., Brunger A.T. Architecture of the synaptotagmin-SNARE machinery for neuronal exocytosis. Nature. 2015;525:62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature14975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández-Chacón R., Königstorfer A., Südhof T.C. Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium regulator of release probability. Nature. 2001;410:41–49. doi: 10.1038/35065004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai J., Tucker W.C., Chapman E.R. PIP2 increases the speed of response of synaptotagmin and steers its membrane-penetration activity toward the plasma membrane. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nsmb709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrick D.Z., Sterbling S., Cafiso D.S. Position of synaptotagmin I at the membrane interface: cooperative interactions of tandem C2 domains. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9668–9674. doi: 10.1021/bi060874j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo W., Herrick D.Z., Cafiso D.S. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate alters synaptotagmin 1 membrane docking and drives opposing bilayers closer together. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2633–2641. doi: 10.1021/bi200049c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takamori S., Holt M., Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James D.J., Khodthong C., Martin T.F. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:355–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez-Lara Á., Thapa A., Jahn R. PtdInsP2 and PtdSer cooperate to trap synaptotagmin-1 to the plasma membrane in the presence of calcium. eLife. 2016;5:e15886. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyenhuis S.B., Thapa A., Cafiso D.S. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate controls the cis and trans interactions of synaptotagmin 1. Biophys. J. 2019;117:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai J., Chapman E.R. The C2 domains of synaptotagmin--partners in exocytosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L., Shin O.H., Rosenmund C. Phosphatidylinositol phosphates as co-activators of Ca2+ binding to C2 domains of synaptotagmin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15845–15852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Bogaart G., Thutupalli S., Jahn R. Synaptotagmin-1 may be a distance regulator acting upstream of SNARE nucleation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:805–812. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honigmann A., van den Bogaart G., Jahn R. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate clusters act as molecular beacons for vesicle recruitment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:679–686. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S., Li Y., Ma C. Synaptotagmin-1 C2B domain interacts simultaneously with SNAREs and membranes to promote membrane fusion. eLife. 2016;5:e14211. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araç D., Chen X., Rizo J. Close membrane-membrane proximity induced by Ca(2+)-dependent multivalent binding of synaptotagmin-1 to phospholipids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrick D.Z., Kuo W., Cafiso D.S. Solution and membrane-bound conformations of the tandem C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin 1: evidence for bilayer bridging. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;390:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brewer K.D., Bacaj T., Rizo J. Dynamic binding mode of a synaptotagmin-1-SNARE complex in solution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:555–564. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courtney N.A., Bao H., Chapman E.R. Synaptotagmin 1 clamps synaptic vesicle fusion in mammalian neurons independent of complexin. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4076. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12015-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mace K.E., Biela L.M., Reist N.E. Synaptotagmin I stabilizes synaptic vesicles via its C(2)A polylysine motif. Genesis. 2009;47:337–345. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi H., Shahin V., Edwardson J.M. Interaction of synaptotagmin with lipid bilayers, analyzed by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2550–2558. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu K., Carroll J., Davletov B. Vesicular restriction of synaptobrevin suggests a role for calcium in membrane fusion. Nature. 2002;415:646–650. doi: 10.1038/415646a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seven A.B., Brewer K.D., Rizo J. Prevalent mechanism of membrane bridging by synaptotagmin-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3243–E3252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310327110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C.C., Seikowski J., Walla P.J. Control of membrane gaps by synaptotagmin-Ca2+ measured with a novel membrane distance ruler. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5859. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martens S., Kozlov M.M., McMahon H.T. How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science. 2007;316:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hui E., Johnson C.P., Chapman E.R. Synaptotagmin-mediated bending of the target membrane is a critical step in Ca(2+)-regulated fusion. Cell. 2009;138:709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai A.L., Tamm L.K., Cafiso D.S. Synaptotagmin 1 modulates lipid acyl chain order in lipid bilayers by demixing phosphatidylserine. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:25291–25300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Z., Schulten K. Synaptotagmin’s role in neurotransmitter release likely involves Ca(2+)-induced conformational transition. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1156–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z., Liu H., Chapman E.R. Reconstituted synaptotagmin I mediates vesicle docking, priming, and fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:1159–1170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai J., Earles C.A., Chapman E.R. Membrane-embedded synaptotagmin penetrates cis or trans target membranes and clusters via a novel mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:25427–25435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M906729199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai Y., Lou X., Shin Y.K. The synaptotagmin 1 linker may function as an electrostatic zipper that opens for docking but closes for fusion pore opening. Biochem. J. 2013;456:25–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J., Littleton J.T. Transmembrane tethering of synaptotagmin to synaptic vesicles controls multiple modes of neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420312112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray D., Honig B. Electrostatic control of the membrane targeting of C2 domains. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermaas J.V., Tajkhorshid E. Differential membrane binding mechanics of synaptotagmin isoforms observed in atomic detail. Biochemistry. 2017;56:281–293. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hempel T., Plattner N., Noé F. Coupling of conformational switches in calcium sensor unraveled with local Markov models and transfer entropy. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:2584–2593. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bykhovskaia M. Calcium binding promotes conformational flexibility of the neuronal Ca(2+) sensor synaptotagmin. Biophys. J. 2015;108:2507–2520. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jo S., Lim J.B., Im W. CHARMM-GUI membrane builder for mixed bilayers and its application to yeast membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westhead E.W. Lipid composition and orientation in secretory vesicles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;493:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb27186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hui E., Bai J., Chapman E.R. Ca2+-triggered simultaneous membrane penetration of the tandem C2-domains of synaptotagmin I. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1767–1777. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tran H.T., Anderson L.H., Knight J.D. Membrane-binding cooperativity and coinsertion by C2AB tandem domains of synaptotagmins 1 and 7. Biophys. J. 2019;116:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyubimov A.Y., Uervirojnangkoorn M., Brunger A.T. Advances in X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) diffraction data processing applied to the crystal structure of the synaptotagmin-1 / SNARE complex. eLife. 2016;5:e18740. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gould I.R., Skjevik A.A., Walker R.C. Lipid17: a comprehensive AMBER force field for the simulation of zwitterionic and anionic lipids. in prep. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piana S., Donchev A.G., Shaw D.E. Water dispersion interactions strongly influence simulated structural properties of disordered protein states. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:5113–5123. doi: 10.1021/jp508971m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feller S.E., Zhang Y.H., Brooks B.R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salomon-Ferrer R., Götz A.W., Walker R.C. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:3878–3888. doi: 10.1021/ct400314y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roe D.R., Cheatham T.E., III PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou H.X. The affinity-enhancing roles of flexible linkers in two-domain DNA-binding proteins. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15069–15073. doi: 10.1021/bi015795g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacDougall D.D., Lin Z., Anantharam A. The high-affinity calcium sensor synaptotagmin-7 serves multiple roles in regulated exocytosis. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018;150:783–807. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bian X., Saheki Y., De Camilli P. Ca 2+ releases E-Syt1 autoinhibition to couple ER-plasma membrane tethering with lipid transport. EMBO J. 2018;37:219–234. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.