Main Text

Allostery is a common regulatory mechanism in proteins. Many proteins exist in dynamic equilibrium between active and inactive states (1). Transitions between these states are facilitated by a network of allosteric interactions that cannot be easily identified by comparative analysis of structure and dynamics of residues found in the end points. Current structure-based virtual screening and lead optimization protocols rely on static structures of these various states to predict the impact of substituent modifications on binding free energies (2). Coupling between substituents, nonadditivity, severely limits the accuracy of linear scoring functions (3, 4, 5). Although allostery is a frequent cause of nonadditivity, determining the effects of allostery on the energetic landscape of substrate binding presents a major challenge. Boulton et al. have started to address this in this issue of Biophysical Journal (6). By analyzing the thermodynamic cycle of the cAMP-binding domain (CNBD) of the HCN4 channel, they present a new NMR-based approach to characterize the allosteric mechanisms underlying nonadditivity resulting from simultaneous base substitution (adenine to guanine in cGMP) and phosphate substitution (equatorial exocyclic oxygen to sulfur in Rp-AMPS) of cAMP.

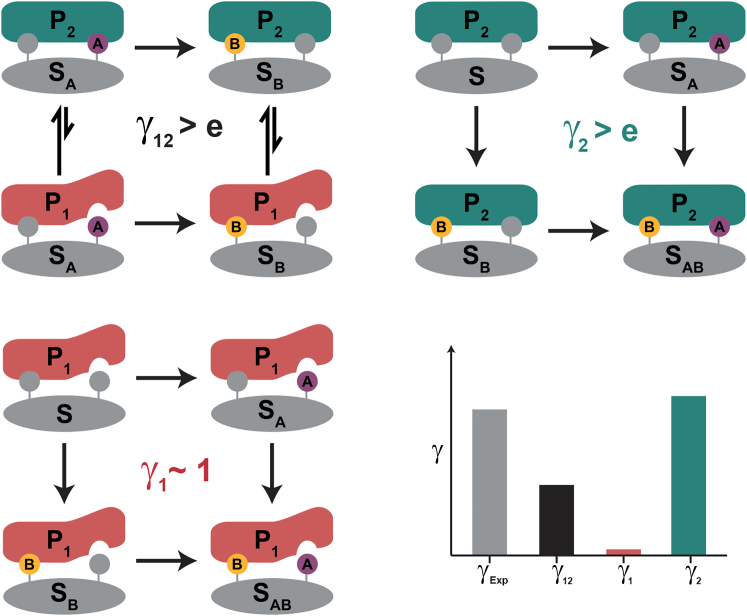

The CNBD apo state of HCN4 is a stereotypical allosteric switch, dynamically sampling both an autoinhibitory (P1) and an active (P2) state at a rate that is fast on the NMR timescale. cAMP binding selects and stabilizes the active state, whereas the three analogs of cAMP (Rp-AMPS, cGMP, and Rp-cGMPS) modulate the P1 ⇔ P2 equilibrium (Fig. 1; for details, please refer to manuscript). Therefore, nonadditivity could result purely from the P1 ⇔ P2 exchange (γ12) and/or from state-specific nonadditivity (γ1, γ2). This requires precise knowledge of the population of P1 () and P2 () when saturated with each ligand (Sj), which NMR is ideally suited to provide. In this case, because the exchange rate is fast, the observed chemical shift is a population-weighted average of P1 and P2 states, allowing for determination of the populations from two-dimensional spectra. They found that the conformational exchange (γ12) contributed to the dominant source of nonadditivity was due to unfavorable interactions in the active state conformation (γ2).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Observed Equilibria. To see this figure in color, go online.

Molecular dynamics simulations showed that Rp-AMPS induces “steric frustration” between F689 and L663 in the active state. Chemical shift covariance analyses (CHESCA), a method developed by the Melacini lab in 2011 (7,8), revealed the extensive allosteric network, including F689, regulating the P1 ⇔ P2 transition. A frustration-silencing mutation, F689A, was found to elevate both the γ12 and γ2 sources of nonadditivity. Subsequent CHESCA analysis of the F689A mutants revealed a dramatic reduction in the allosteric network. Although Boulton et al. do not discuss the implications of altering the allosteric network on the thermodynamic cycle, the effect is clear.

These results demonstrate a powerful first step in the development of a robust method for interrogating the thermodynamics of ligand binding to allosteric receptors in addition to breaking down the contributions of conformational exchange (γ12) and state-specific effects (γ1, γ2). Boulton et al. clearly demonstrate how changes in the allosteric network can directly affect substituent nonadditivity. It is clear that incorporation of the allosteric networks identified through CHESCA analysis into structure-based virtual screening could be highly beneficial. It will be interesting to see the application of this method to slow to intermediate exchange systems using chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) or relaxation dispersion (RD) experiments to determine populations (9,10).

Editor: Elizabeth Komives.

References

- 1.Saleh T., Rossi P., Kalodimos C.G. Atomic view of the energy landscape in the allosteric regulation of Abl kinase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:893–901. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guedes I.A., Pereira F.S.S., Dardenne L.E. Empirical scoring functions for structure-based virtual screening: applications, critical aspects, and challenges. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1089. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum B., Muley L., Klebe G. Non-additivity of functional group contributions in protein-ligand binding: a comprehensive study by crystallography and isothermal titration calorimetry. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;397:1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasief N.N., Hangauer D. Additivity or cooperativity: which model can predict the influence of simultaneous incorporation of two or more functionalities in a ligand molecule? Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;90:897–915. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherkasov A., Muratov E.N., Tropsha A. QSAR modeling: where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:4977–5010. doi: 10.1021/jm4004285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulton S., Van K., Melacini G. Allosteric mechanisms of non-additive substituent contributions to protein-ligand binding. J. Biophys. 2020;119:1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selvaratnam R., Chowdhury S., Melacini G. Mapping allostery through the covariance analysis of NMR chemical shifts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:6133–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017311108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulton S., Selvaratnam R., Melacini G. Implementation of the NMR CHEmical shift covariance analysis (CHESCA): a chemical biologist’s approach to allostery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1688:391–405. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7386-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallurupalli P., Sekhar A., Kay L.E. Probing conformational dynamics in biomolecules via chemical exchange saturation transfer: a primer. J. Biomol. NMR. 2017;67:243–271. doi: 10.1007/s10858-017-0099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallurupalli P., Hansen D.F., Kay L.E. Structures of invisible, excited protein states by relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11766–11771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804221105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]