Abstract

Previous studies of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have suggested that structural variants (SVs) play an important role but these were mainly studied in subjects of European ancestry and focused on coding regions. In this study, we sought to address the role of SVs in non-European populations and outside of coding regions. To that end, we generated whole genome sequence (WGS) data on 875 individuals, including 205 ADHD cases and 670 non-ADHD controls. The ADHD cases included 116 African Americans (AA) and 89 of European Ancestry (EA) with SVs in comparison with 408 AA and 262 controls, respectively. Multiple SVs and target genes that associated with ADHD from previous studies were identified or replicated, and novel recurrent ADHD-associated SV loci were discovered. We identified clustering of non-coding SVs around neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathways, which are involved in neuronal brain function, and highly relevant to ADHD pathogenesis and regulation of gene expression related to specific ADHD phenotypes. There was little overlap (around 6%) in the genes impacted by SVs between AA and EA. These results suggest that SVs within non-coding regions may play an important role in ADHD development and that WGS could be a powerful discovery tool for studying the molecular mechanisms of ADHD

Subject terms: Genomics, Mutation, Population genetics, Next-generation sequencing, Neuroscience

Introduction

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has a prevalence of ~ 6–8% in children with male patients outnumbering females by almost double1. Symptoms persist into adulthood in over two thirds of cases, causing significant life-long impairments2,3. In the last decade, multiple studies have attempted to investigate the genetic susceptibility of ADHD, most notably by assessing the enrichment of copy number variations (CNVs)4 and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) from genome-wide association studies (GWAS)5. However, the current understanding of this complex trait is incomplete and attempts to replicate previous studies have been inconsistent, due in part to the highly heterogenous phenotype of ADHD, as well as other factors, such as complicated molecular mechanisms underlying ADHD networks and limitations of genotyping arrays to study structural variations (SV)6. Previous studies also show that the susceptibility of ADHD is more likely to be impacted by biological pathways instead of a particular gene6–8, and by structural variations (SVs), such as copy number variations (CNVs), inversions, translocations that may play important roles in the regulation of ADHD gene networks9,10. Most of previously published studies have focused on coding regions and have been carried out primarily in patients of European ancestry while intronic and intergenic regions were often omitted from analyses. However, non-coding genomic structural variations and non-coding DNA sequences have been shown to play important roles in many human diseases, including neurodevelopmental diseases such as autism and intellectual disability11,12. In this regard, the most recent large GWAS studies on 55,374 individuals, including 20,183 ADHD patients, highlighted that variants in non-coding regions, such as non-coding RNA and intergenic region were significantly associated with ADHD susceptibility13. In addition, previous studies have largely focused on European Caucasian populations leaving out studies in African populations and other populations.

To address the limitations of the previous studies of ADHD, in this study we have generated deep whole genome sequencing (WGS) data on 875 individuals, including 205 ADHD patients and 670 non-ADHD controls, in order to explore the impact of SVs, especially SVs within non-coding regions, on the pathogenesis of ADHD. We have also included a significant number of African Americans in the study, including 116 cases and 408 controls, to expand the analysis into another population other than Europeans. The results suggest that SVs within non-coding regions play critical roles in the molecular mechanisms underlying ADHD and that population-specific SVs are present. This information would be useful for future studies of ADHD genetic network regulation and drug development.

Results

Exonic/splicing SVs impact structure of genes related to neurodevelopment procedures

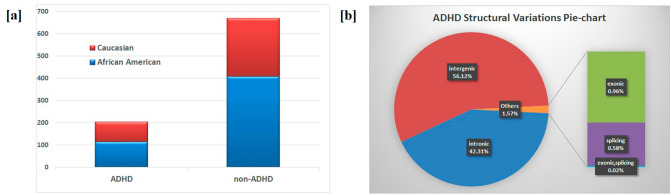

Approximately 160,000 structural variations (SVs) were identified in ADHD patients (Fig. 1b), of those, 0.96% were classified as exonic, 0.59% as splicing, 42.3% as intronic and 56.13% as intergenic. Exonic/splicing usually have more significant impacts since they alter the coding regions and splicing sites directly As expected, they accounted for a small proportion (~ 1.5%) of the total of which 37 were significantly with ADHD threshold 0.05 and 9 with threshold 0.01 (Table 1). In addition to the 37 exonic/splicing SVs that associated with ADHD we identified 451 rare ADHD-associated SVs in AA (Supplementary Table 2a) and 382 in EA (Supplementary Table 2b), 41 SVs are only existed in ADHD cases and were absent from controls (Table 2). A recurrent 320 bp long deletion was identified for three AA ADHD patients at chr5:171723712–171724032, at the splicing site of non-coding RNA LOC100288254.

Figure 1.

Patient summary and distribution of structural variations (SVs) for ADHD vs control. (a) represents the number of ADHD patients and non-ADHD controls with race information; (b) distribution of structural variations (SVs) for 206 ADHD patients based on whole genome sequencing (WGS). Intergenic and intronic variations accounted for over 98% of the SVs.

Table 1.

ADHD-associated Exonic/splicing SVs that passed the statistical threshold 0.01.

| Gene_ID | Structure | Type | Num in ADHD | Num in controls | OR | Chi-square p value | Adjusted Chi-square p value | Fisher's Exact p value | Adjusted Fisher's Exact p value | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPS53 | Exonic | Deletion | 18 | 20 | 3.55 | 2.57E−04 | 1 | 3.79E−04 | 1 | AA |

| MPEG1 | Exonic | Insertion | 9 | 7 | 4.8 | 2.61E−03 | 1 | 2.82E−03 | 1 | AA |

| SPATA9 | Exonic | Insertion | 29 | 44 | 2.39 | 3.84E−03 | 1 | 4.01E−03 | 1 | EA |

| DEPDC1 | Exonic | Translocation | 6 | 3 | 7.33 | 4.76E−03 | 1 | 5.07E−03 | 1 | AA |

| OR4N4 | Splicing | Deletion | 70 | 183 | 1.87 | 5.90E−03 | 1 | 4.62E−03 | 1 | AA |

| LOC101927079 | Splicing | Deletion | 70 | 183 | 1.87 | 5.90E−03 | 1 | 4.62E−03 | 1 | AA |

| LOC100134391 | Exonic | Deletion | 5 | 2 | 9.09 | 7.19E−03 | 1 | 7.22E−03 | 1 | AA |

| LINC00469 | Exonic | Deletion | 5 | 2 | 9.09 | 7.19E−03 | 1 | 7.22E−03 | 1 | AA |

| LMLN | Exonic, splicing | Deletion | 4 | 1 | 14.44 | 9.99E−03 | 1 | 9.79E−03 | 1 | AA |

Table 2.

Rare recurrent exonic/splicing SVs that were only found in ADHD patients.

| Gene_ID | Structure | Type | Occurrences in ADHD | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC100288254 | Splicing | Deletion | 3 | AA |

| ANO9 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| ARHGEF18 | Exonic | Insertion | 2 | EA |

| BPTF | Exonic | Translocation | 2 | AA |

| C20orf27 | Splicing | Deletion | 2 | EA |

| C20orf27 | Exonic | Translocation | 2 | EA |

| CASP8 | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | AA |

| CDHR5 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| DEAF1 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| DRD4 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| EPS8L2 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| FLG2 | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | EA |

| FLG-AS1 | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | EA |

| GCNT4 | Exonic | Insertion | 2 | EA |

| HMGB3 | Exonic | Translocation | 2 | AA |

| HRAS | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| IRF7 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| KHDC1 | Splicing | Translocation | 2 | AA |

| LMNTD2 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| LOC143666 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| LOC692247 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| LRRC56 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| MIR137 | Exonic | Insertion | 2 | EA |

| MIR210 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| MIR210HG | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| NOC2L | Splicing | Duplication | 2 | EA |

| PHRF1 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| PTDSS2 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| RASSF7 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| RNH1 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| SAMD11 | Splicing | Duplication | 2 | EA |

| SCT | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| SENP3 | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | EA |

| SENP3-EIF4A1 | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | EA |

| SLC35B3 | Splicing | Deletion | 2 | AA |

| SPART | Exonic | Insertion | 2 | AA |

| SV2B | Exonic | Deletion | 2 | AA |

| TMEM80 | Splicing | Inversion | 2 | AA |

| TSACC | Splicing | Deletion | 2 | AA |

| WDR72 | Exonic | Translocation | 2 | AA |

| ZNF585B | Exonic | Translocation | 2 | EA |

SVs within non-coding regions reveal known and possibly novel ADHD-associated genes

Beside exonic/splicing SVs, we also evaluated association of non-coding SVs in ADHD. The novel intronic SVs are listed in Supplementary Tables 3, 4, 5 for AA, EA, and meta-analysis, respectively. The majority of selected ADHD-associated SV-genes were impacted by SVs within non-coding regions (Table 3), furthermore based on the ADHDgene database14, there are no known exonic/splicing SV-genes from previous studies passed the statistic threshold. However, a novel exonic deletion in IQSEC3 passed the ethnicity meta-analysis (p value = 0.0083, Supplementary Table 6). IQSEC3 is a neuronal exchange gene related to speech, i.e. childhood apraxia of speech, and down-regulated in autism and schizophrenia15.

Table 3.

Selected SV-associated genes targets based on p value.

| Ethnicity | Gene_ID | Structure | Type | OR | Chi-square p value | adjusted Chi-square p value | Fisher's Exact p value | adjusted Fisher's Exact p value | Previous knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | RFTN1 | Intronic | Translocation | 2.88 | 2.19E−06 | 0.025 | 3.52E−06 | 0.041 | Novel |

| EA | GPD2 | Intergenic | Insertion | 3.12 | 1.61E−04 | 1 | 2.20E−04 | 1 | Novel |

| EA | PPEF1 | Intronic | Translocation | 4.15 | 1.80E−04 | 1 | 2.36E−04 | 1 | Novel |

| AA | VPS53 | Exonic | Deletion | 3.55 | 2.57E−04 | 1 | 3.79E−04 | 1 | Novel |

| AA | NOX4 | Intergenic | Insertion | 12.95 | 2.82E−04 | 1 | 5.65E−04 | 1 | Novel |

| AA | DEPDC1 | Exonic | Translocation | 7.33 | 4.76E−03 | 1 | 5.07E−03 | 1 | Novel |

| AA | OR4N4 | Splicing | Deletion | 1.87 | 5.90E−03 | 1 | 4.62E−03 | 1 | Novel |

| EA | GFOD1 | Intronic | Insertion | 3.06 | 7.86E−03 | 1 | 6.96E−03 | 1 | Known |

| meta | IQSEC3 | Exonic | Deletion | 1.82 | 8.30E−03 | 1 | 6.76E−03 | 1 | Novel |

| AA | LMLN | Exonic,splicing | Deletion | 14.44 | 9.99E−03 | 1 | 9.79E−03 | 1 | Novel |

| EA | CDH13 | Intronic | Deletion | 2.14 | 1.57E−02 | 1 | 1.23E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | SLC7A10 | Intronic | Insertion | 1.81 | 2.06E−02 | 1 | 1.99E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | NTRK2 | Intronic | Deletion | 1.72 | 2.33E−02 | 1 | 1.88E−02 | 1 | Known |

| EA | GRM5 | Intronic | Insertion | 3.58 | 2.90E−02 | 1 | 2.89E−02 | 1 | Known |

| EA | CLOCK | Intronic | Insertion | 1.99 | 3.57E−02 | 1 | 2.84E−02 | 1 | Known |

| EA | CHRNA3 | Intronic | Translocation | 2.48 | 3.70E−02 | 1 | 2.90E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | CTNNA2 | Intergenic | Deletion | 1.63 | 3.95E−02 | 1 | 3.81E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | NRSN1 | Intergenic | Duplication | 4.53 | 4.39E−02 | 1 | 2.95E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | GRIN2A | Intergenic | Translocation | 4.53 | 4.39E−02 | 1 | 2.95E−02 | 1 | Known |

| AA | HTR1F | Intronic | Deletion | 1.59 | 4.41E−02 | 1 | 4.32E−02 | 1 | Known |

An example network pathway of SVs within non-coding regions is neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, a pathway critical in neuronal brain function, known to be highly relevant to ADHD development and regulation of differential gene expression in different ADHD-related brain regions16,17. Non-coding SVs such as intronic deletion of HTR1F, intronic translocation of CHRNA3, intergenic translocation of GRIN2A, and intronic insertions of GRM5, were found significantly enriched in ADHD patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Non-coding SV-genes in neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway.

| Gene ID | Name | AA | EA |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHRNA3 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3 (neuronal) | Intronic translocation p value 0.037 | |

| CHRNA4 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 4 (neuronal) | Intronic insertion p value 0.078 | |

| GABRG1 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, gamma 1 | Intronic deletion p value 0.061 | |

| GRIN2A | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2A | Intergenic translocation p value 0.044 | |

| GRM5 | Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 5 | Intronic insertion p value 0.029 | |

| HTR1F | 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1F | Intronic deletion p value 0.044 | |

| HTR2C | 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C | Intronic deletion p value 0.073 | |

| MC4R | Melanocortin 4 receptor | Intergenic deletion p value 0.073 | |

| OPRM1 | Opioid receptor, mu 1 | Exonic deletion p value 0.052 | |

| OXTR | Oxytocin receptor | Intergenic deletion p value 0.085 |

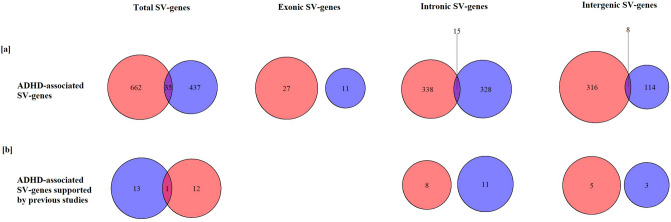

Structural variations show differences in two ethnicities

No obvious differences in SV prevalence types between the AA and EA (Supplementary Fig. 1), however, impacted ADHD-associated SV-genes, which reach statistical significance, are different between two ethnicities (Fig. 2). There were 686 ADHD-associated SV-genes for AA based on statistical tests (Supplementary Table 3), and 439 ADHD-associated SV-genes for EA (Supplementary Table 4). Only 34 genes shared between two ethnicities (Supplementary Table 5), which counted 5%/8% for entire SV-gene set. Meta-analysis identified 234 ADHD-associated SV-genes (Supplementary Table 6), and only four ADHD-associated SV-genes were found in previous literatures (Table 5). Actually, genes in meta-analysis results are still impacted by ethnicities, for example MYBPC1 has intergenic SVs with p value 0.017 in meta-analysis, and the p value is 0.79 in AA and 0.0032 in EA, in other words, this meta-significant SV-gene passed through meta-analysis because highly ADHD-associated in EA and not significant at all in AA.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of overlap SV-genes between AA and EA, including all SVs, exonic SVs, intronic SVs, and intergenic SV, respectively. (a) SV-genes which significantly associated with ADHD patients (chi-square p value < = 0.05); (b) SV-genes supported by previous ADHD studies and significantly associated with ADHD patients (chi-square p value < = 0.05).

Table 6.

Significant ADHD-associated non-coding SV-genes which have previously ADHD literature support in AA and EA, respectively.

| Gene | AA intronic SV significant associated with ADHD | EA intronic SV significant associated with ADHD | AA intergenic SV significant associated with ADHD | EA intergenic SV significant associated with ADHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGBL1 | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| CAMK1D | Yes | – | – | – |

| CDH13 | – | Yes | – | – |

| CDH23 | – | Yes | – | – |

| CHRNA3 | – | Yes | – | – |

| CLOCK | – | Yes | – | – |

| CTNNA2 | – | – | Yes | – |

| GFOD1 | – | Yes | – | – |

| GPC5 | – | Yes | – | – |

| GRIN2A | – | – | Yes | – |

| GRM5 | – | Yes | – | – |

| HCN1 | Yes | – | – | – |

| HTR1F | Yes | – | – | – |

| HTR3B | Yes | – | – | – |

| ITGAE | – | Yes | – | – |

| KCTD15 | – | – | – | Yes |

| LINGO2 | – | Yes | – | – |

| MYBPC1 | – | – | Yes | Yes |

| MYO5B | – | Yes | – | – |

| NCKAP5 | – | Yes | – | – |

| NRSN1 | – | – | Yes | – |

| NTRK2 | Yes | – | – | – |

| SLC6A1 | – | – | Yes | – |

| SLC7A10 | Yes | – | – | – |

| TCERG1L | Yes | – | – | – |

| TSPAN8 | Yes | – | – | – |

Small overlap between two ethnicities.

Discussion

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurobiological disorder in children, with a prevalence of 6–8%6. In this study, we identified 37 exonic/splicing SVs, several involving genes that have been previously reported in neurological and mental diseases, such as VPS53, which has been previously associated with a neurological conditions and Parkinson disease18. Consequently, we identified 40 novel recurrent SV genes associated with ADHD, where the SVs occurred exclusively in ADHD or have frequency less than 0.5% in non-ADHD controls. Those novel recurrent SVs could be also important in ADHD development. For example, we identified a novel 320 bp deletion at splicing sites of non-coding RNA LOC100288254, which is a recurrent SV in three independent ADHD patients and only seen in ADHD patients. Additional notable recurrent rare SVs included an exonic insertion of a non-coding RNA, MIR137, which has been shown to play a significant role in neural development and neoplastic transformation19, splicing inversion in DRD4 which has previously been implicated in ADHD20, and an exonic translocation of BPTF, which causes expressive language delay and intellectual disability21. BPTF, which exonic translocation was identified in two independent individuals, was considered as a candidate gene in neurodevelopmental disorder based on exome pool-seq22, and believed to be the cause of syndromic developmental, speech delay, postnatal microcephaly, and dysmorphic features in recent study21. We also observed that the non-coding RNA LINC00461, which wasone of the 12 significant loci in the study by Demontis et al.13, had an intronic insertion in six ADHD patients with chi-square p value = 0.02.

In addition, this study reveals that SVs within non-coding regions may be more critical in ADHD biological networks than they used to believe. One typical example is the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, a pathway critical in neuronal brain function, known to be highly relevant to ADHD pathogenesis. In this study, 17 SV genes were found significantly different between ADHD patients and controls, including four genes CHRNA3, GRM5, HTR1F, GRIN2A which were supported by previous literature4,23–25. All the identified structural variations related to this pathway are either intronic or intergenic. Similar situations were found in other neurodevelopmental pathways, such as MAPK signaling pathway and Axon guidance. Functional role of SVs in non-coding regions in ADHD therefore warrant further investigation. We also show that there is only a small portion of overlap between the two ethnicities of SV impacted genes, and the result was further replicated as we limited the SV-genes to known ADHD genes based on the ADHD gene database14. 25 ADHD-associated SV-genes have been previously studied and reported in the literature (Table 6), and only one gene, AGBL1, with intergenic SVs shows statistically significant difference in both ethnicities. AGBL1 was the top locus in the largest ADHD genome-wide meta-analysis done26 and mutation in this gene showed significant association with learning performance27. Taken together, the results suggest that impacted ADHD-associated genes differ between the two ethnicities, suggesting that ADHD analysis without population information could miss potential disease genes.

Table 5.

Significant ADHD-associated non-coding SV-genes which have previously ADHD literature support based on meta-analysis.

| Gene | Name | Intronic SV significant associated with ADHD | Intergenic SV significant associated with ADHD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYBPC1 | Myosin binding protein C, slow type | – | Yes |

| CDH23 | Cadherin-related 23 | Yes | – |

| KANSL1 | KAT8 regulatory NSL complex subunit 1 | – | Yes |

| CDH13 | Cadherin 13 | Yes | – |

While the majority of those ADHD-associated SVs are located in non-coding regions, the question is how these SVs impact ADHD pathways in the two ethnicity groups: are the pathways different or do the SVs impact same pathways but different gene modules? In order to explore the answers, we further mapped these SVs within non-coding regions into the highly studied ADHD pathways, including neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway. For the ADHD SV-genes which are significantly different in ADHD and non-ADHD controls (p value ≤ 0.05) or have a trend towards significance (p value ≤ 0.1), 10 of them belong to neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway and five genes are AA SV-genes and the left are EA specific SV-genes (Table 4). The results also suggest that SVs, especially SVs within non-coding regions, impact the same gene families but different gene members, such as intronic SVs of CHRNA3 in AA versus CHRNA4 in EA, and intronic SVs of HTR1F in AA versus HTR2C in EA. Based on the enrichment studies for those ADHD-associated pathways, it suggests that the SVs within non-coding regions impact the same ADHD-associated pathways for both ethnicities, but different genes in the same gene families.

In summary, we have conducted a genomic-level study in ADHD patients using whole genome sequencing that takes non-coding genes/regions and ethnicity factors into consideration. The results show that non-coding region SVs and non-coding genes may play a role in the development and progression of ADHD, and WGS may be a powerful tool to explore ADHD molecular mechanisms. Additionally, our study highlights that genomic-level population differences exist between Caucasian and African American patients, especially for non-coding SVs in neuronal genes and that these variants may influence response to specific medications. For the potential evolutional advantages of ADHD in human history28, the same ADHD-associated pathways though different genes were involved in the adaption to the environmental selection for survival in the two major human populations. On the other hand, we admit that the current study is limited by the sample size because of the significant expense of WGS. The SVs highlighted by our study warrant further study and confirmation.

Methods

Patient selection

The patients were randomly selected from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC), archived in the biobank of the Center for Applied Genomics (CAG) at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), with full electronic medical record (EMR). Psychopathology of the cohort was assessed using a computerized, structured interview (GOASSESS)29. The diagnosis of ADHD was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) originally, and later confirmed by DSM-V. There were 205 ADHD cases, including 116 African Americans (AA) and 89 European Americans (EA), and 670 controls, including 408 AA and 262 EA (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1a).

Structural variations (SVs) detections

The average coverage for WGS data is 30 ×. The structural variations (SVs), including insertions, deletions, duplications, inversions and translocations, were detected by MANTA Structural Variant Caller developed by Illumina30. For quality control, we only included SVs that passed MANTA’s default filters, which required the length of corresponding SVs to be at least 50 bp and rated “PASS” based on MANTA threshold. Passing SVs were stratified into different classes based on their sequence content. Using the hg19 GENCODE reference sequence, if the start and end points of a SV mapped within an exon, it was annotated as “exonic’; if the start and end points of a SV were located within an intronic region and the SV does not spanned an exon, it was annotated as “intronic”; if the SV was located across exon/intron border sites, it was annotated as “splicing”; and the remaining SVs were annotated as “intergenic”.

Exonic, intronic and splicing SVs were annotated with the impacted gene, and intergenic SVs were annotated with their closet gene based on genomic locus. The corresponding annotated gene, either the SVs impacted gene or the closet gene, was named as “SV-gene”. Association of SV-genes in ADHD were calculated for AA and EA independently using Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Bonferroni correction was used for correction of multiple testing by the number of tested variations or genes. Significance was set at 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. We only included risk variants in downstream analyses, i.e. SVs that had odd ratios greater than 1. Meta-analysis (combined Chi-square test) was applied when combing two ethnicities together. Pathway analysis is based on DAVID bioinformatics platforms.

Ethic statement

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all experimental protocols were approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects or, if subjects are under 18, from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Center for Applied Genomics (CAG) staff and supports from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

Author contributions

Y.L., X.C., P.M.A.S. and H.H. designed the study. L.T., D.L. and H.Q., P.M.A.S. and H.H. acquired the data, L.T., D.L. and H.Q., X.C. and Y.L. analyzed the data. Y.L., X.C., H.Q. and J.G. wrote the article and prepared figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yichuan Liu and Xiao Chang.

Contributor Information

Patrick M. A. Sleiman, sleimanp@email.chop.edu

Hakon Hakonarson, hakonarson@email.chop.edu.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-71307-0.

References

- 1.Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43:434–442. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visser SN, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2014;53:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbaresi WJ, et al. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2013;131:637–644. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elia J, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation study associates metabotropic glutamate receptor gene networks with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 2011;44:78–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lantieri F, Glessner JT, Hakonarson H, Elia J, Devoto M. Analysis of GWAS top hits in ADHD suggests association to two polymorphisms located in genes expressed in the cerebellum. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010;153B:1127–1133. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly JJ, Glessner JT, Elia J, Hakonarson H. ADHD & pharmacotherapy: past, present and future: a review of the changing landscape of drug therapy for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2015;49:632–642. doi: 10.1177/2168479015599811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta MT, Arcos-Burgos M, Muenke M. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): complex phenotype, simple genotype? Genet. Med. 2004;6:1–15. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000110413.07490.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akutagava-Martins GC, Rohde LA, Hutz MH. Genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2016;16:145–156. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2016.1130626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glessner JT, et al. Copy number variation meta-analysis reveals a novel duplication at 9p24 associated with multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Genome Med. 2017;9:106. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0494-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glessner JT, Connolly JJ, Hakonarson H. Rare genomic deletions and duplications and their role in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2012;12:345–360. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Lupski JR. Non-coding genetic variants in human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:R102–110. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulayeva K, et al. Genomic structural variants are linked with intellectual disability. J. Neural. Transm (Vienna) 2015;122:1289–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00702-015-1366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demontis D, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:63–75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, et al. ADHDgene: a genetic database for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1003–1009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thevenon J, et al. 12p13.33 microdeletion including ELKS/ERC1, a new locus associated with childhood apraxia of speech. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;21:82–88. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khadka S, et al. Multivariate Imaging Genetics Study of MRI Gray Matter Volume and SNPs Reveals Biological Pathways Correlated with Brain Structural Differences in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lima Lde A, et al. An integrative approach to investigate the respective roles of single-nucleotide variants and copy-number variants in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22851. doi: 10.1038/srep22851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kun-Rodrigues C, et al. A systematic screening to identify de novo mutations causing sporadic early-onset Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:6711–6720. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoudi E, Cairns MJ. MiR-137: an important player in neural development and neoplastic transformation. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:44–55. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tovo-Rodrigues L, et al. DRD4 rare variants in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): further evidence from a birth cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e85164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankiewicz P, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the chromatin remodeler BPTF causes syndromic developmental and speech delay, postnatal microcephaly, and dysmorphic features. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popp B, et al. Exome Pool-Seq in neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:1364–1376. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polina ER, et al. ADHD diagnosis may influence the association between polymorphisms in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes and tobacco smoking. Neuromol. Med. 2014;16:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s12017-013-8286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franke B, et al. The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:960–987. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JI, et al. The GRIN2B and GRIN2A Gene Variants Are Associated With Continuous Performance Test Variables in ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1087054716649665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neale BM, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:884–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta CM, Gruen JR, Zhang H. A method for integrating neuroimaging into genetic models of learning performance. Genet Epidemiol. 2017;41:4–17. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelley-Tremblay JF, Rosen LA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an evolutionary perspective. J. Genet. Psychol. 1996;157:443–453. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1996.9914877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calkins ME, et al. The Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort: constructing a deep phenotyping collaborative. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2015;56:1356–1369. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1220–1222. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.