Abstract

The use of faecal microbial markers as non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer (CRC) has been suggested, but not fully elucidated. Here, we have evaluated the importance of Parvimonas micra as a potential non-invasive faecal biomarker in CRC and its relation to other microbial biomarkers. The levels of P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria were quantified using qPCR in faecal samples from a population-based cohort of patients undergoing colonoscopy due to symptoms from the large bowel. The study included 38 CRC patients, 128 patients with dysplasia and 63 controls. The results were validated in a second consecutive CRC cohort including faecal samples from 238 CRC patients and 94 controls. We found significantly higher levels of P. micra in faecal samples from CRC patients compared to controls. A test for P. micra could detect CRC with a specificity of 87.3% and a sensitivity of 60.5%. In addition, we found that combining P. micra with other microbial markers, could further enhance test sensitivity. Our findings support the potential use of P. micra as a non-invasive biomarker for CRC. Together with other microbial faecal markers, P. micra may identify patients with “high risk” microbial patterns, indicating increased risk and incidence of cancer.

Subject terms: Cancer, Biomarkers, Gastroenterology

Introduction

The prognosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) depends to a large extent on tumour stage at diagnosis and advanced disease is associated with poorer life expectancy. Current screening strategies are primarily based on detection of human faecal haemoglobin (F-Hb) and colonoscopy, with the latter being both time consuming, costly and uncomfortable for the patient. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of the gut microbiota in CRC development1–5, and a better understanding of the microbial patterns connected to CRC may serve to improve the accuracy and accessibility of today’s CRC screening.

Accumulating evidence suggests that dysbiosis of the gut increases the risk of developing CRC6–11. Studies have shown a structural segregation of bacterial species between CRC patients and healthy subjects. Some bacteria are altered or more frequently present in patients with CRC, whereas some species are suppressed compared to healthy individuals12. Lately, a microbial driver-passenger model for carcinogenesis has been suggested, where some bacteria promote cancer while others accumulate due to higher fitness in the resulting altered microenvironment13. Bacteria associated with carcinogenesis (drivers) often produce genotoxins that cause double stranded DNA breakage and mutations that can lead to tumour initiation and progression. Bacteria associated with inflammatory responses accelerating tumour progression can be drivers, but are more often thought to be passengers14.

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a part of the commensal gut and oral cavity flora, but has been linked to pathological conditions including appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), periodontitis and CRC15–18. Preclinical models have demonstrated multiple mechanisms by which F. nucleatum may promote CRC progression, including E-cadherin-mediated activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling15. F. nucleatum has also been suggested to negatively regulate the anti-tumor immune response19. Colibactin toxin-producing (clbA +) bacteria have been suggested to promote CRC development through inducing double-stranded DNA breaks and cellular senescence20. However, recently the role of colibactin as a potential driver has been debated21. Parvimonas micra is, like F. nucleatum, commensal in the oral cavity and has been linked to pathogenesis leading to intracranial abscesses, pericarditis and necrotising fasciitis, as well as CRC4,14,22–25. However, the role of P. micra in CRC progression is still largely unknown, and the potential of P. micra as a faecal marker for CRC detection has not been fully elucidated.

Using faecal microbiota in CRC screening would serve as a non-invasive complement to today’s F-Hb screening and could further identify patients that would benefit from colonoscopy. Our group has earlier published a study showing associations between F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria and CRC2. In the present study, we investigated the potential of P. micra as a non-invasive faecal marker for detection of CRC using the same cohort. Our findings were further validated in a second larger cohort. The diagnostic performance of combined tests of P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria were also evaluated.

Results

P. micra is more abundant in faeces of patients with CRC

The level of P. micra was analysed in faecal samples from 38 cancer patients, 128 patients with dysplasia, and 63 matched controls from the FECSU cohort, which is a population-based cohort of patients undergoing colonoscopy due to large bowel symptoms. Our findings were further validated using faecal samples from 238 CRC patients and 94 matched controls from the U-CAN cohort of consecutive CRC patients. The clinical characteristics of the study patients from the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts can be found in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study patients from the FECSU cohort.

| Total | Control | Dysplasia | Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 229 | n = 63 | n = 128 | n = 38 | |

| Age (%) | ||||

| ≤ 59 | 33 (14.4) | 6 (9.5) | 23 (18.0) | 4 (10.5) |

| 60–69 | 88 (38.4) | 21 (33.3) | 55 (43.0) | 12 (31.6) |

| 70–79 | 82 (35.8) | 26 (41.3) | 39 (30.5) | 17 (44.7) |

| ≥ 80 | 26 (11.4) | 10 (15.9) | 11 (8.6) | 5 (13.2) |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Female | 103 (45.0) | 30 (47.6) | 55 (43.0) | 18 (47.4) |

| Male | 126 (55.0) | 33 (52.4) | 73 (57.0) | 20 (52.6) |

| Location (%) | n = 166 | |||

| Right colon | 45 (27.1) | n.a | 34 (26.6) | 11 (28.9) |

| Left colon | 74 (44.6) | n.a | 57 (44.5) | 17 (44.7) |

| Rectum | 47 (28.3) | n.a | 37 (28.9) | 10 (26.3) |

| Stage (%) | ||||

| I | n.a | n.a | 2 (5.4) | |

| II | n.a | n.a | 20 (54.1) | |

| III | n.a | n.a | 8 (21.6) | |

| IV | n.a | n.a | 7 (18.9) | |

Abbreviations: n.a., not applicable.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of study patients from the U-CAN cohort.

| Total | Control | Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 332 | n = 94 | n = 238 | |

| Age (%) | |||

| ≤ 59 | 56 (16.9) | 15 (16.0) | 41 (17.2) |

| 60–69 | 120 (36.1) | 33 (35.1) | 87 (36.6) |

| 70–79 | 113 (34.0) | 33 (35.1) | 80 (33.6) |

| ≥ 80 | 43 (13.0) | 13 (13.8) | 30 (12.6) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 136 (41.0) | 41 (43.6) | 95 (39.9) |

| Male | 196 (59.0) | 53 (56.4) | 143 (60.1) |

| Location (%) | |||

| Right colon | n.a | 48 (20.2) | |

| Left colon | n.a | 41 (17.2) | |

| Rectum | n.a | 149 (62.6) | |

| Stage (%) | |||

| I | n.a | 46 (20.4) | |

| II | n.a | 77 (34.2) | |

| III | n.a | 65 (28.9) | |

| IV | n.a | 37 (16.4) | |

n.a., not applicable.

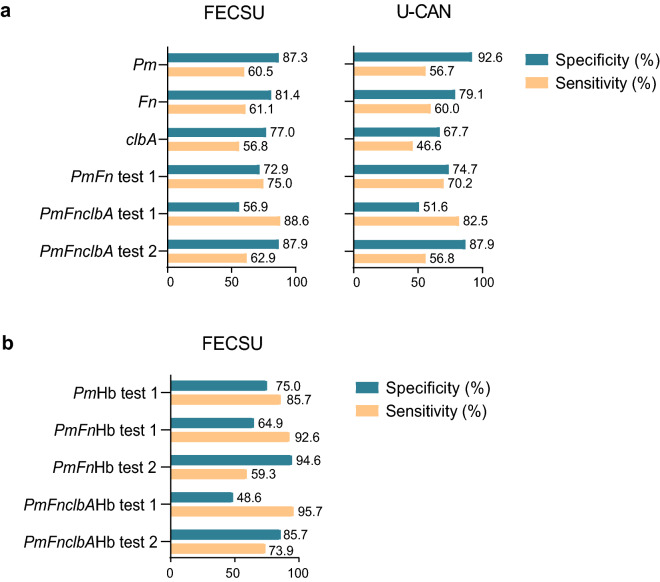

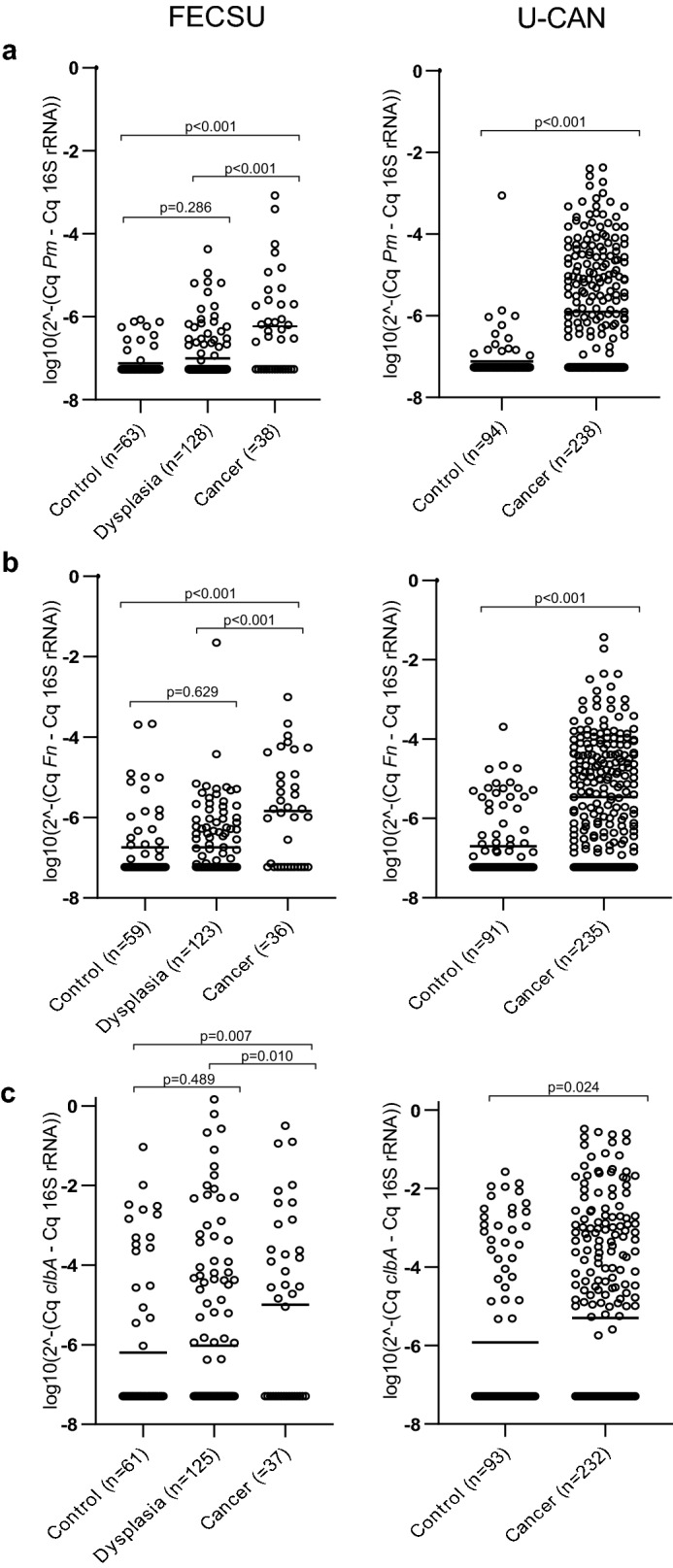

A qPCR assay targeting the rpoB gene was used to detect P. micra. P. micra was significantly more abundant in faecal samples from CRC patients compared to controls in the FECSU cohort (P < 0.001; Fig. 1A). No significant difference was found between patients with dysplasia and controls (P = 0.286), and significantly higher levels of P. micra were found in samples from CRC patients compared to patients with dysplasia (P < 0.001). The finding of significantly higher levels of P. micra in faecal samples from CRC patients compared to controls could be validated in the U-CAN cohort (P < 0.001; Fig. 1A). The area under the ROC curve for detection of CRC for the FECSU cohort was 0.726 (Fig. 2). A cut-off (2.5 × 10^-7) for a positive detection of P. micra was selected using Youden’s index. Using the optimised cut-off, a test for P. micra could detect cancer with a sensitivity of 60.5% and a specificity of 87.3% in the FECSU cohort (Table 3; Fig. 3A). For the U-CAN cohort, the sensitivity was 56.7% and the specificity was 92.6% (Fig. 3A). No clear associations of P. micra with clinical characteristics of CRC patients of the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts were found, including tumour stage and site (Supplementary Table S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

Increased levels of specific microbial markers are detected in faeces of CRC patients. Scatter plots are used to illustrate the relative levels of (A) P. micra (Pm), (B) F. nucleatum (Fn), and (C) clbA + bacteria (clbA) in faeces of control patients, and patients diagnosed with dysplasia or CRC from the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts. Horizontal lines indicate mean relative expression calculated by the 2-ΔCq method with the total microbial 16S rRNA gene DNA as reference.

Figure 2.

ROC curves displaying the specificity and the sensitivity for P. micra (Pm), F. nucleatum (Fn), and clbA + bacteria (clbA) to detect CRC. ROC-curves were calculated using the levels for the specific marker as indicated and cancer/no cancer. The levels of a specific marker in each sample was given as a relative quantification calculated by the 2-ΔCt method with the total microbial 16S rRNA gene DNA as reference.

Table 3.

Microbial alterations in faeces of study patients from the FECSU cohort.

| Total | Control | Dysplasia | Cancer | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 229 | n = 63 | n = 128 | n = 38 | ||

| P. micra (%) | |||||

| Low | 177 (77.3) | 55 (87.3) | 107 (83.6) | 15 (39.5) | < 0.001 |

| High | 52 (22.7) | 8 (12.7) | 21 (16.4) | 23 (60.5) | |

| F. nucleatum (%) | |||||

| Low | 166 (76.1) | 48 (81.4) | 104 (84.6) | 14 (38.9) | < 0.001 |

| High | 52 (23.9) | 11 (18.6) | 19 (15.4) | 22 (61.1) | |

| clbA + bacteria (%) | |||||

| Low | 154 (69.1) | 47 (77.0) | 91 (72.8) | 16 (43.2) | 0.001 |

| High | 69 (30.9) | 14 (23.0) | 34 (27.2) | 21 (56.8) | |

χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables.

Figure 3.

Performance of single faecal microbial markers or combinations of markers in CRC detection. Sensitivity and specificity for CRC detection is displayed for a test of (A) P. micra (Pm), F. nucleatum (Fn), or clbA + bacteria (clbA), as well as combined tests using several microbial markers for the FECSU and U-CAN cohort, and (B) for combined tests using microbial markers and immunochemical F-Hb (Hb) for the FECSU cohort. For test 1, a positive test result was given to samples with at least one positive marker. For test 2, a positive test result was given to samples with at least two positive markers.

The relative abundance of P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria in CRC patients

F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria have been previously assessed in the FECSU cohort2. Here, DNA was extracted from another aliquot of the same stool sample using an improved technique as described below. Furthermore, in this study we used other established PCR assays from the literature to detect both F. nucleatum and the 16S rRNA gene. While the clbA assay is the same as in the previous study, we here present a relative quantification using the 16S rRNA gene. Previous findings of significantly enriched levels of F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria in faeces of CRC patients could be replicated in the current study and validated in the U-CAN cohort (Fig. 1B, C). The area under the ROC-curve was for this study 0.707 for F. nucleatum and 0.630 for clbA + bacteria (Fig. 2). Using the cut-offs of 9.5 × 10^-7 for F. nucleatum and 8.8 × 10^-6 for clbA + bacteria, F. nucleatum could detect CRC with a sensitivity of 61.1% and a specificity of 81.4%, and clbA + bacteria detected CRC with a sensitivity of 56.8% and a specificity of 77.0% in the FECSU cohort (Table 3; Fig. 3A). These results were further validated in the U-CAN cohort, with F. nucleatum showing a sensitivity of 60.0% and specificity of 79.1% to detect CRC, and clbA + bacteria showing a sensitivity of 46.6% and specificity of 67.7% (Fig. 3A).

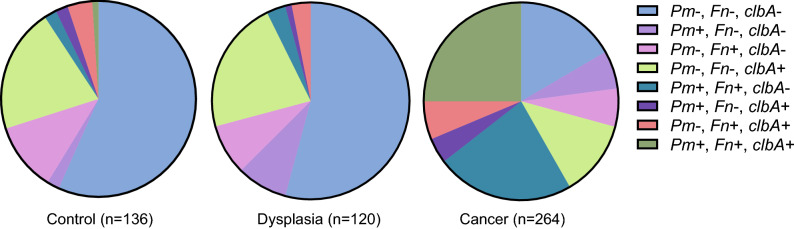

When dissecting the relative abundance of P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria in faecal samples, we found a quite similar pattern between controls and dysplasias, and a severely altered pattern in CRC patients (Fig. 4). P. micra was rarely detected as the sole bacterial marker in faecal samples from CRC patients, but was instead often found in combination with F. nucleatum (rs 0.620; P < 0.001), with or without clbA + bacteria. Faecal samples in which P. micra or F. nucleatum were found in combination with clbA + bacteria alone were rare. These findings may indicate a cooperative effect between some bacterial markers, P. micra and F. nucleatum in particular, in the carcinogenic process.

Figure 4.

The distribution of specific microbial markers in faeces of CRC patients. Circle diagrams are used to illustrate the abundance of P. micra (Pm), F. nucleatum (Fn) and clbA + bacteria (clbA) in faecal samples with all three markers evaluated of control patients, and patients diagnosed with dysplasia or CRC from the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts.

A combined test of faecal P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria predicts CRC

We further explored the performance of combined tests of P. micra with other microbial markers. A combined test of P. micra with F. nucleatum, or F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria, where a positive test result was described as one or more positive marker, enhanced sensitivity to 75.0%, or 88.6%, respectively, but with the corresponding decrease in specificity to 72.9% and 56.9%, respectively (Fig. 3A). Similar results were found also for the U-CAN cohort, with a sensitivity of 70.2%, and 82.5%, and a specificity of 74.7% and 51.6%, respectively for P. micra in combination with F. nucleatum alone or together with clbA + bacteria (Fig. 3A). A more restricted test, where a positive test result was given to faecal samples positive for two or more markers, did not improve the quality of detection compared to P. micra alone (Fig. 3A).

The performance of P. micra in combined tests with microbial markers and/or F-Hb

We previously reported the diagnostic performance of immunochemical F-Hb for CRC detection in the FECSU cohort2. Here, we further analysed if the performance for a test of P. micra alone or with additional microbial markers could be enhanced by the addition of F-Hb. Since F-Hb was only available for the FECSU cohort, these studies were restricted to this cohort. We found that addition of F-Hb could enhance the sensitivity of the test for P. micra to 85.7%, while decreasing the specificity to 75.0% (Fig. 3B). Addition of F-Hb to the test of P. micra and F. nucleatum, as well as F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria, further enhanced the sensitivity to 92.6% and 95.7%, respectively (Fig. 3B). However, the addition of F-Hb reduced specificity of these tests to 64.9% and 48.6%, respectively (Fig. 3B). A more restricted test, where a positive test result was given to faecal samples with two or more positive markers, restored specificity to 94.6% and 85.7%, respectively, but with the consequence of reduced sensitivity to 59.3% and 73.9%, respectively, for the combination of F-Hb with P. micra in combination with F. nucleatum alone or together with clbA + bacteria (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

In this study, we used targeted qPCR assays to investigate faecal microbial markers for CRC detection and applied a second larger cohort for validation. To apply qPCR for detection is an affordable and clinically very relevant approach. We found a significantly higher abundance of P. micra in faecal samples from CRC patients compared to controls. A test for P. micra in faeces could detect cancer with a sensitivity of 60.5% or 56.7% and a specificity of 87.3% or 92.6% in the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts, respectively. We further showed that the sensitivity of the assay could be enhanced by adding microbial markers F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria, as well as F-Hb, but with a resulting decrease in specificity. This study thereby suggests P. micra as a candidate microbial marker for a non-invasive screening panel, with the potential of improving the diagnostic performance.

Our findings are supported by previous studies showing an alteration of P. micra in both faeces and tissue samples from CRC patients compared to controls. Findings of P. micra in faeces were mainly based on 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing4,22–26, but a few studies have also applied targeted qPCR assays25,27. In a study by Yu et al., a microbial signature was identified, including P.micra, which could distinguish CRC metagenomes from controls in several independent cross-ethnic cohorts25. They further employed qPCR measurements of P. micra and F. nucleatum, and demonstrated that combined analyses of these two markers could accurately classify patients with CRC. In the present study, we proceed from a population-based cohort better representing a true screening cohort. This cohort, in addition to CRC patients, also included patients with dysplasia. However, no significant difference in levels of P. micra between faecal samples from controls and dysplasias could be found. This suggests that P. micra is not present in pre-cancerous lesions and is more likely a passenger rather than a driver of tumourigenesis, a conclusion also supported by findings of Wong et al.27 Our results therefore indicate that P. micra represents as a poor detection marker of pre-cancerous lesions, which is not optimal from a screening perspective. P. micra is however found evenly distributed throughout all stages of CRC, suggesting that early stages of CRC can be identified, which was also suggested in the study by Yu et al.25.

In this study, P. micra was found to detect CRC with a similar sensitivity as F. nucleatum. However, fewer control samples presented with a positive test result for P. micra, resulting in a higher specificity of testing. Interestingly, P. micra was found to be highly correlated to F. nucleatum in faeces, and similar findings were presented by Yu et al.25 These bacteria, both being oral pathogens, may therefore interact in the carcinogenic process. The pathogenicity of F. nucleatum in CRC has been suggested to be mediated partly through stimulation of inflammatory processes28. Little is known about the role of P. micra in CRC progression, but it may be that P. micra and F. nucleatum interact to potentiate a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Interestingly, P. micra and F. nucleatum have been shown to aggregate and form biofilms in vitro.29 Additionally, one study on periodontitis indicated that P. micra may stimulate immunity through interactions with pattern-recognition NOD2 receptors30. Further studies are needed to elucidate a possible pro-tumourigenic role of P. micra.

The population-based cohort used in this study included patients who had undergone a colonoscopy at the University Hospital in Umeå, Sweden. Indications for colonoscopy were gastrointestinal symptoms of large bowel disease, visible blood in faeces and/or positive F-Hb. Thus, even though regarded as healthy, patients in the control group still manifested with bowel symptoms that could be linked to an altered gut microbiota. Therefore, it is possible that the specificity of a combined test of microbial markers would be improved in a randomized screening cohort. There is considerable inter-individual variation of the gut flora, and many factors including lifestyle, age, genetics and medication, especially antibiotics treatment, affect the composition. In order to avoid this type of possible bias, we designed control groups matched in age and gender. Also, no patients included had ongoing antibiotic treatment, even though a previous antibiotic treatment could still have altered the gut microbiota. Furthermore, our study included a validation cohort, which increases the chance for true positive results. The microbial composition is also affected by the faecal sampling and sample storage. In this study, faeces from a single randomly taken sample was used. Even though appealing from a clinical perspective, using a single sample from a small amount of stool increases the risk of a non-representative result. In order to achieve more reliable results, repetitive faecal samples would be preferred. It should be noted also that this study was not based on a randomized screening cohort, and the efficacy of a test quantifying P. micra in CRC screening therefore remains to be evaluated.

Using faecal samples for screening provides an easy non-invasive method. If used in the clinic, screening participation would likely increase and thereby also the potential for early detection and patient survival. Today, F-Hb is the most used non-invasive screening method. Tests for immunochemical F-Hb (FIT) are however poor at detecting non-bleeding lesions and do not have high enough sensitivity to detect advanced adenoma or cancer31. In this study, a test for P.micra alone had a slightly decreased sensitivity compared to immunochemical F-Hb to detect CRC2. A combined test of P.micra and F-Hb had superior sensitivity compared to F-Hb alone, which could further be enhanced by additional microbial markers. Combined analyses of P. micra and F-Hb in faecal samples from CRC patients has been assessed by Wong et al., showing similar results27. Microbial markers could thereby serve as a complement to F-Hb screening in order to find non-bleeding lesions, to increase the sensitivity of the test, and to better specify patients for further colonoscopy examination. Finding risk patterns using a larger number of microbial markers is likely to increase the accuracy of the method. If a patient would be identified by a high-risk microbial pattern, a colonoscopy would however still be needed in order to verify the diagnosis. Patients without colonoscopy findings, would need to be followed regularly by repetitive colonoscopy exams, which may lead to an unnecessary psychological burden.

In conclusion, P. micra is a promising candidate for a future faecal non-invasive combined CRC screening test including microbial markers and F-Hb. We suggest that detection of “high risk” microbial patterns may facilitate the finding of patients with increased CRC cancer risk. Future studies combining different microbial markers could possibly enhance the tests accuracy. These studies may also lead to a better understanding of the role of bacteria in CRC tumour development and progression.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

This study is based on cohorts from the Faecal and Endoscopic Colorectal Study in Umeå (FECSU) and the Uppsala-Umeå Comprehensive Cancer Consortium (U-CAN). The FECSU cohort includes patients who underwent colonoscopy at the University Hospital in Umeå, Sweden, between the years 2008–2013, and has been previously described2. In brief, indications for colonoscopy were gastrointestinal symptoms that may indicate large bowel disease, visible blood in faeces and/or positive F-Hb. Exclusion criteria were colonoscopy within one week, dementia and low performance status, including mental and physical disabilities. All colonoscopies were performed according to standard routines at the endoscopy unit. Biopsies were taken when clinically relevant and evaluated by a pathologist in clinical routine handling. All neoplastic lesions were further subdivided into low grade dysplasia, high grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. In cases where multiple lesions were found, the most severe was used for classification. In total, 1997 patients were invited to participate in the FECSU study. 861 patients denied participation, leaving 1,136 patients included. Of these, 39 were diagnosed with CRC and 135 with low or high grade dysplasia. The U-CAN project is a collaboration between Umeå University and Uppsala University, which longitudinally collects blood, tissue, faeces, radiological data, and clinical data over time from all enrolled CRC patients. In Umeå, more than 1,200 patients with CRC have been recruited since the start in 2010. Stool sample collection was performed during the years 2010 to 2014. During these years a total of 684 patients were included, out of which 260 CRC patients (38%) left a stool sample prior to the start of treatment.

Few patients (n = 14) were included in both cohorts, but separate stool samples were collected for the different studies and therefore these patients were not excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden (dnr 08-184 M and dnr 2016/219–31), and in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All included individuals have signed a written form of consent.

Study patients included

For FECSU2, depletion of faecal samples from some patients resulted in inclusion of a total of 38 cancer patients, 128 patients with dysplasia and 63 controls for this study. Controls were selected from the patients recorded with no pathological findings and were matched by age and gender. Patients with IBD and hyperplastic polyps were excluded from the controls.

For U-CAN, limiting amounts of DNA extracted from the faecal samples resulted in a total of 238 patients included in the study. One hundred controls were density matched by age and gender and selected from the FECSU cohort, using the criteria described above. After exclusions due to depleted faecal samples or limited amounts of DNA extracted, 94 controls remained in the study.

Stool sample collection and storage

Stool samples were collected by the patients in their home. Tubes for stool sample collection and study information were either sent by post together with the invitation for colonoscopy (for FECSU patients, as previously described2) or given to the patients at the time of diagnosis (U-CAN patients). For the FECSU cohort, included patients were asked to leave stool samples before starting the pre-colonoscopy cleansing procedure. Stool samples from CRC patients of the U-CAN cohort were collected before the start of cancer treatment. For both cohorts, stool tubes assigned for DNA extraction and microbial analyses contained 5 ml of preservative buffer, RNAlater (Ambion), and were stored for a maximum of 7 days at room temperature prior to centrifugation for 20 min at 2000 rpm, disposal of excess fluid, and freezing at -80 °C. According to previous results, RNAlater was shown to preserve both DNA yield and quality of stool samples stored at room temperature2.

Detection of microbial markers in faeces using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

DNA was extracted from approximately 0.2 g stool using the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA kit.

(Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In previous work of the FECSU cohort2, DNA was extracted using a different kit. Since the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA kit showed superior DNA yield and quality, DNA was re-extracted from another aliquot of the stool sample for the FECSU cohort. P. micra, F. nucleatum and clbA + bacteria were detected in the DNA by qPCR. All reactions were run in duplicates utilising the QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). In case of discrepancies in Cq values between duplicates (standard deviation > 0.5), the sample was rerun in duplicates 1–2 times until a stable duplicate was obtained. Samples with poor PCR performance consistently showing discrepant duplicates were excluded from the analysis. These exclusions included 11 and 6 faecal samples from FECSU and U-CAN cohorts, respectively, for the F. nucleatum assay, and 6 and 7 faecal samples from the FECSU and U-CAN cohorts, respectively, for the clbA assay. Primers and probes used for the different assays have been previously described and are listed with references in Supplementary Table S3. The performance of the qPCR assays was verified by analyses of replicates, serial dilutions, melting curves, and separation on agarose gels. qPCR efficiencies were stable and comparable between different amplicons and between SYBR Green I and TaqMan probe based assays. Markers not amplified within 38 cycles were defined as negative. P. micra 20,468 (DSZM), F. nucleatum subsp. nucleatum Knorr (ATCC 25,586), and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 were used as positive controls for the respective PCR reactions. The levels of P. micra, F. nucleatum, and clbA + bacteria were presented as a relative quantification with the total microbial content using the 16S rRNA gene as reference as validated in the literature (Supplementary Table S3) and calculated using the 2—ΔCt method. Cycle conditions used were as follows: For P. micra and F. nucleatum – 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 45 s: For clbA + bacteria—2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min: For 16S rRNA,—2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of: 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (SPSS Inc.). χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences in continuous variables between groups. Correlations between continuous variables were analysed using the Spearman´s rank correlation test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated using the variable for P. micra, F. nucleatum or clbA + bacteria and cancer diagnosis/no cancer diagnosis. The Youden´s index was used to identify the cut-off for the different assays, resulting in an optimal trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in the detection of cancer. This cut-off was used to identify faecal samples as positive (with high levels of the indicated marker) or negative (with low levels of the indicated marker).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the patients who participated in the study and to the staff of the Endoscopy unit, Umea University Hospital, Umea, Sweden, for invaluable assistance. We further thank Åsa Stenberg and Rolf Claesson for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden, and the County Council of Vasterbotten. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: T.L., A.L.B., C.Z., V.E., M.D., S.N.W., P.L., I.L., S.E., R.P.; acquisition of data: T.L., A.L.B., C.Z., V.E.; data analyses: T.L., A.L.B., C.Z., S.E.; drafting of the manuscript: T.L., A.L.B., S.E. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: T.L., A.L.B., C.Z., V.E., M.D., S.N.W., P.L., I.L., S.E., R.P. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Umeå University.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72132-1.

References

- 1.Liang Q, et al. Fecal bacteria act as novel biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;23:2061–2070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eklof V, et al. Cancer-associated fecal microbial markers in colorectal cancer detection. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141:2528–2536. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie YH, et al. Fecal clostridium symbiosum for noninvasive detection of early and advanced colorectal cancer: test and validation studies. EBioMedicine. 2017;25:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter NT, Ruffin MTT, Rogers MA, Schloss PD. Microbiota-based model improves the sensitivity of fecal immunochemical test for detecting colonic lesions. Genome Med. 2016;8:37. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amitay EL, Krilaviciute A, Brenner H. Systematic review: Gut microbiota in fecal samples and detection of colorectal neoplasms. Gut Microbes. 2018;9:293–307. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1445957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu N, et al. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients. Microb. Ecol. 2013;66:462–470. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan CA, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, inflammation, and colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;70:395–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hale VL, et al. Shifts in the fecal microbiota associated with adenomatous polyps. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:85–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flemer B, et al. Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:633–643. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakatsu, G. et al. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun.6, 8727. 10.1038/ncomms9727 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Feng, Q. et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun.6, 6528. 10.1038/ncomms7528 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC. Linking gut microbiota to colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 2017;8:3378–3395. doi: 10.7150/jca.20497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjalsma H, Boleij A, Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:575–582. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong SH, et al. Gavage of fecal samples from patients with colorectal cancer promotes intestinal carcinogenesis in germ-free and conventional mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1621–1633. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhinai, E. A., Walton, G. E. & Commane, D. M. The role of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer causation. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 5295; 10.3390/ijms20215295 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Cochrane, K., Robinson, A. V., Holt, R. A. & Allen-Vercoe, E. A survey of Fusobacterium nucleatum genes modulated by host cell infection. Microb. Genom.6, e000300. 10.1099/mgen.0.000300 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Liang JQ, et al. A novel faecal Lachnoclostridium marker for the non-invasive diagnosis of colorectal adenoma and cancer. Gut. 2020;69:1248–1257. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zorron Cheng Tao Pu, L. et al. Microbiota profile is different for early and invasive colorectal cancer and is consistent throughout the colon. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 433–437 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gur C, et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015;42:344–355. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalmasso G, Cougnoux A, Delmas J, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Bonnet R. The bacterial genotoxin colibactin promotes colon tumor growth by modifying the tumor microenvironment. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:675–680. doi: 10.4161/19490976.2014.969989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wassenaar, T. M. E. coli and colorectal cancer: a complex relationship that deserves a critical mindset. Crit. Rev. Microbio.l44, 619–632 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Drewes JL, et al. High-resolution bacterial 16S rRNA gene profile meta-analysis and biofilm status reveal common colorectal cancer consortia. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2017;3:34. doi: 10.1038/s41522-017-0040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purcell, R. V., Visnovska, M., Biggs, P. J., Schmeier, S. & Frizelle, F. A. Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep.7, 11590. 10.1038/s41598-017-11237-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Shah MS, et al. Leveraging sequence-based faecal microbial community survey data to identify a composite biomarker for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2018;67:882–891. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:70–78. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saffarian, A. et al. Crypt- and mucosa-associated core microbiotas in humans and their alteration in colon cancer patients. mBio.10, 4. 10.1128/mBio.01315-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wong SH, et al. Quantitation of faecal Fusobacterium improves faecal immunochemical test in detecting advanced colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2017;66:1441–1448. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostic AD, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horiuchi, A., Kokubu, E., Warita, T. & Ishihara, K. Synergistic biofilm formation by Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Anaerobe.62, 102100. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102100 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Marchesan J, et al. TLR4, NOD1 and NOD2 mediate immune recognition of putative newly identified periodontal pathogens. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2016;31:243–258. doi: 10.1111/omi.12116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, J. K., Liles, E. G., Bent, S., Levin, T. R. & Corley, D. A. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med.160, 171. 10.7326/M13-1484 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.