Key Points

Question

In patients with platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial cancer, is nab-paclitaxel more effective and better tolerated than paclitaxel?

Findings

In this randomized phase 2 clinical trial with 199 patients randomized to nab-paclitaxel or paclitaxel, there was no significant difference between nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel for median progression-free survival (3.4 months vs 3.0 months, respectively).

Meaning

Nab-paclitaxel was not superior and had more toxic effects than paclitaxel; overall response rates of either taxanes, however, were higher than previously reported and comparable to the immune checkpoint inhibitors, suggesting that the taxanes remain a reasonable option in this setting.

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel in patients with platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment options for platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) are limited, and outcomes remain poor. Nab-paclitaxel is an albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel showing promising activity and tolerability in a prior single-arm trial.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel in platinum-refractory mUC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this investigator-initiated, open-label, phase 2 randomized clinical trial conducted across Canada and Australia from January 2014 to April 2017, eligible patients had histologically confirmed, radiologically evident mUC of the urinary tract. Mixed histologic findings, except small cell, were permitted provided UC was the predominant histologic finding. All patients had received platinum-based chemotherapy either in the metastatic setting or were within 12 months of perioperative chemotherapy. Patients with prior taxane chemotherapy were not included. Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) 0 to 2 and adequate organ function.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to nab-paclitaxel, 260 mg/m2, or paclitaxel, 175 mg/m2, every 3 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Among 199 patients, median age was 67 (range, 24-88) years; 144 (72%) were men; 167 (84%) were ECOG PS 0-1; 59 (30%) had liver metastases; and 110 (55%) were within 6 months of prior platinum-based chemotherapy. At a median follow-up of 16.4 months, there was no significant difference between nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel for median PFS (3.4 months vs 3.0 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.92; 90% CI, 0.68-1.23; 1-sided P = .31). Median overall survival was 7.5 months for nab-paclitaxel vs 8.8 months for paclitaxel (HR, 0.95; 90% CI, 0.70-1.30; 1-sided P = .40); and objective response rate (ORR) was 22% for nab-paclitaxel vs 25% for paclitaxel (P = .97). Grade 3/4 adverse events were more frequent with nab-paclitaxel (64/97 [66%]) compared with paclitaxel (45/97 [46%]), P = .009; but peripheral sensory neuropathy was similar (all grades, 72/97 [74%] vs 64/97 [66%]; grade 3/4, 7/97 [7%] vs 3/97 [3%]; P = .27). There were no apparent differences in scores for health-related quality of life.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this open-label, phase 2 randomized clinical trial of patients with platinum-refractory mUC, nab-paclitaxel had similar efficacy to paclitaxel; but worse toxic effects. The ORR with either taxane, however, was higher than previously reported and similar to those reported for the immune checkpoint inhibitors, suggesting that the taxanes remain a reasonable option in this setting.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02033993

Introduction

Urothelial cancer (UC) will account for almost 550 000 new cases of cancer worldwide annually.1 For patients with metastatic disease, platinum-based chemotherapy remains the primary treatment. Despite high response rates, cure rates remain low, reflecting a lack of effective and well tolerated salvage regimens and highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies.

Until the recent introduction of the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), paclitaxel and vinflunine were the most commonly used agents in the platinum-refractory setting.2 Paclitaxel acts by stabilizing microtubules, leading to cell cycle arrest and cell death. It is generally well tolerated, is not associated with nephrotoxic effects, and is relatively inexpensive.3,4

Nab-paclitaxel is an albumin-bound, solvent-free, formulation of paclitaxel that does not require steroid premedication and was designed to improve the therapeutic index of paclitaxel. Nab-paclitaxel was initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for metastatic breast cancer, where it showed superiority over paclitaxel.5 It was subsequently approved for metastatic pancreatic cancer in combination with gemcitabine,6 non–small cell lung cancer in combination with carboplatin,7 and most recently for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in combination with the ICI atezolizumab.8

In platinum-refractory metastatic UC (mUC), we have previously reported that nab-paclitaxel had an objective response rate (ORR) of 28%, a progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.0 months and a median overall survival (mOS) of 10.8 months in a single-arm, phase 2 clinical trial.9 To confirm these results, we conducted a multicenter, randomized phase 2 study in platinum-refractory mUC comparing the efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel to paclitaxel.

Study Design and Participants

This Canadian Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) trial, known as BL12, was an investigator-initiated, international, multicenter, open-label randomized phase 2 cooperative group study. It was designed by a protocol committee that included members of the CCTG and the Australian and New Zealand Urological and Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Group (ANZUP). The protocol is available in Supplement 1. The relevant institutional review boards approved the protocol and all participants gave written informed consent.

Patients

Eligible patients had histologically or cytologically confirmed mUC of the urinary tract (bladder, urethra, ureter, or renal pelvis). Mixed histologies, except small cell, were permitted as long as UC was the predominant histologic finding. Patients had to have locally advanced or metastatic UC with radiological evidence of disease. Prior platinum-based chemotherapy administered in the metastatic setting or within 12 months of the last dose administered in the perioperative setting was mandated prior to enrollment. Other key eligibility criteria included age 18 years or older, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 to 2, and adequate bone marrow, kidney, liver, and cardiac functions; no prior taxane chemotherapy; full recovery from prior treatments to less than grade 2 toxic effects, and no serious concurrent illnesses.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomized according to ECOG PS (0,1 vs 2), liver metastases (yes vs no), lymph node metastases only (yes vs no), hemoglobin levels (<100 vs ≥100 g/L), and interval from prior platinum-based chemotherapy (≤6 months vs >6 months), and medical center. They were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio, to either nab-paclitaxel or paclitaxel. Randomization was performed by the CCTG Statistical and Operations center, using a minimization method that dynamically balanced treatment allocation with equal weight to stratification factors in each center. The database was maintained by CCTG.

Treatments

Patients in arm 1 received nab-paclitaxel, 260 mg/m2, intravenously every 21 days. No premedication was required. Patients in arm 2 received paclitaxel, 175 mg/m2, intravenously every 21 days, with steroid premedication as per institutional standards.

Study Design

The primary objective was to compare PFS between arm 1 and arm 2, among all randomized patients. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from randomization to the first observation of disease progression or death due to any cause. Patients who stopped treatment with study drug and received alternative therapy for mUC prior to documentation of disease progression or death were censored on the last date of assessment without documented disease progression. If patients had not progressed, died, or received alternative therapy for mUC, PFS was censored on the date of the last disease assessment.

Assuming a median PFS of 4 months with paclitaxel, the study was designed to detect a one-third reduction in the hazard of disease progression with nab-paclitaxel (PFS, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.67), which corresponded to a 50% median PFS improvement of 2 months (ie, from 4 to 6 months). Using a 1-sided 5% significance test with 81% power, a minimum of 155 events were required to trigger the final analysis. The estimated sample size was approximately 199 patients, which accounted for a 5% loss to follow-up or withdrawal of consent.

Secondary objectives included comparing overall survival (OS), defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause; objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response defined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors guidelines; clinical benefit rate (ORR and stable disease [SD] >12 weeks), which included patients with only nonmeasurable disease, with noncomplete response (non-CR), nonprogressive disease (non-PD) status; and time to response, defined as the time from the first dose of study drug until the first objective assessment of CR/partial response (PR). Safety profiles of nab-paclitaxel and paclitaxel were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03. Quality of life (QoL) was assessed as time to deterioration by 10 or more points on physical function and global health status subscales of the European Organisation of Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL). Additional analyses were performed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT)-Taxane questionnaire, as well as a comparison of the proportion of patients experiencing a clinically important adverse change in neuropathy scores which was defined as a 10-point change in neuropathy score according to quality-of-life methodology.

All randomized patients were included in the PFS and OS analysis by intention to treat. Safety analysis was conducted on an as-treatment basis, including only patients who had at least 1 dose of nab-paclitaxel or paclitaxel. In the primary analysis, the comparison between the 2 treatment arms was tested using the log-rank stratified by ECOG PS (0,1 vs 2), liver metastases (yes vs no), lymph node metastases only (yes vs no), hemoglobin levels (<100 g/L vs ≥100 g/L) and interval from last platinum-based chemotherapy (≤6 months vs >6 months). Survival distribution for PFS and OS were estimated using Kaplan-Meier plots.10 Stratified Cox regression model was used to adjust for prognostic factors.11 Adverse event data were tested using the Fisher exact test, and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was used to compare RR between treatment arms.12 All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc), and all reported P values are 2-sided unless specified otherwise.

Results

Patient Characteristics

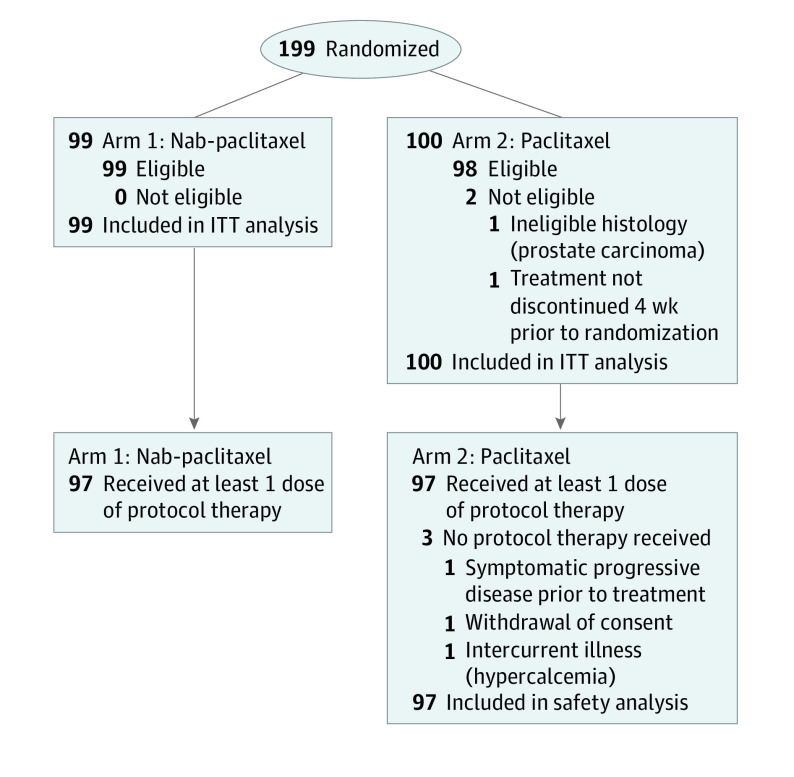

The trial was activated January 2014 and completed enrollment in April 2017 with a total of 199 patients randomized to the study, 160 from Canada, and 39 from Australia. Overall 99 patients received nab-paclitaxel and 100 patients received paclitaxel; 2 patients in the paclitaxel arm were ineligible as shown in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics were similar (Table 1).

Figure 1. Consort Diagram.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nab-paclitaxel (n = 99) | Paclitaxel (n = 100) | All (n = 199) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 67 (24-88) | 68 (35-84) | 67 (24-88) |

| Male | 70 (71) | 74 (74) | 144 (72) |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 or 1 | 83 (84) | 84 (84) | 167 (84) |

| 2 | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | 32 (16) |

| Primary tumor site bladder | 73 (73) | 75 (75) | 148 (74) |

| Hemoglobin level <100 g/L | 10 (10) | 10 (10) | 20 (10) |

| Liver metastasis | 30 (30) | 29 (29) | 59 (30) |

| Lymph node only metastasis | 19 (19) | 18 (18) | 37 (19) |

| Interval from prior platinum | |||

| >6 mo | 45 (46) | 44 (44) | 89 (45) |

| ≤6 mo | 54 (55) | 56 (56) | 110 (55) |

| Prior checkpoint inhibitor | 6 (6) | 6 (6) | 12 (6) |

| Prior cystectomy | 46 (46) | 37 (37) | 83 (42) |

| Prior lines multiagent chemotherapy | |||

| 1 | 89 (90) | 89 (89) | 178 (89) |

| 2 | 10 (10) | 11 (11) | 21 (11) |

Abbreviation: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Progression-Free Survival

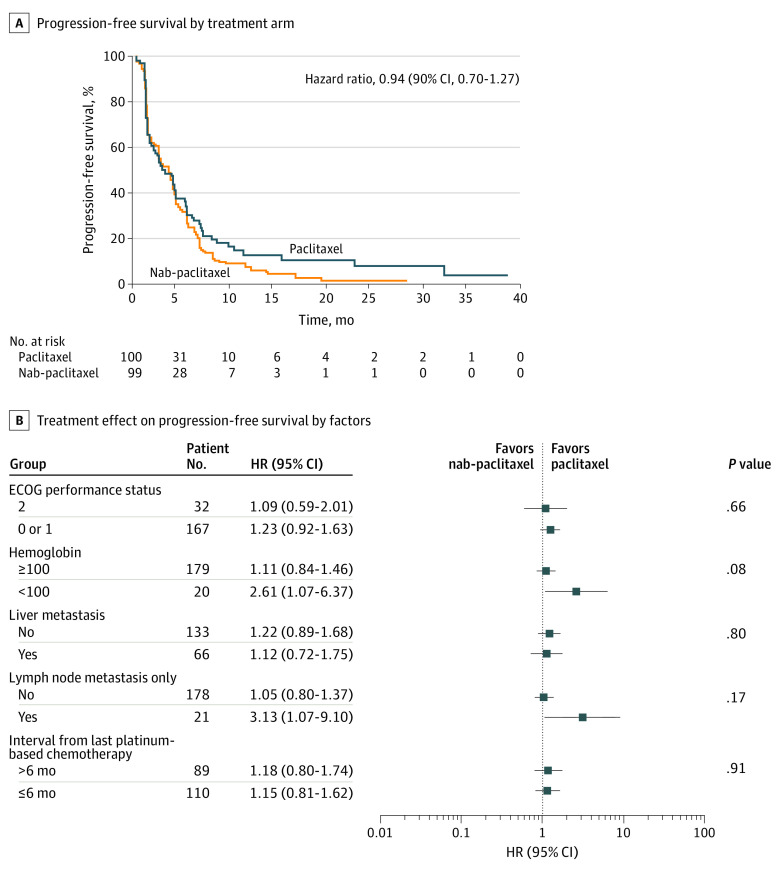

All 199 randomized patients were included in the PFS analysis by intention to treat. Median duration of follow-up was 16.4 months for PFS; 166 patients developed progressive disease (PD) or died without PD (88 nab-paclitaxel, 78 paclitaxel) by data cutoff date of June 30, 2017. Most patients (108) developed PD during treatment; 31 during follow-up; and 27 died without PD. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS distribution by treatment arm are displayed in Figure 2A; the log rank test stratified by a priori factors at randomization was used to test differences between treatment arms (1-sided P = .31). Median PFS was 3.35 months (90% CI, 2.69-4.30) for nab-paclitaxel, whereas it was 3.02 months (90% CI, 2.14-4.40) for paclitaxel. The estimated HR after adjustment for prespecified baseline factors was 0.94 (90% CI, 0.70-1.27) with a 1-sided P value of 0.36. The HR by stratification factors is illustrated in Figure 2B. Treatments after PD: 15 received chemotherapy (9, nab-paclitaxel; 6, paclitaxel), 12 received immunotherapy (6 in each arm).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves.

HR indicates hazard ratio. A, Estimates of progression-free survival distribution by treatment arm. B, Progression-free survival subgroup analysis by stratification factors.

Overall Survival

All 199 patients were included in the OS analysis by intention to treat, and were evaluable for OS and CR. At a median follow-up of 17.4 months, 139 patients had died (72, nab-paclitaxel; 67, paclitaxel) by data cutoff date. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS distribution by treatment arm are displayed in eFigure 1A in Supplement 2; the log rank test stratified by the a priori factors at randomization was used to test the difference between arms. The median survival was 7.46 months (90% CI, 6.44-8.64) in the nab-paclitaxel arm and 8.77 months (90% CI, 6.11-10.61) in the paclitaxel arm. Estimated HR was 0.95 (nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel) with a 90% CI, from 0.70-1.30 (1-sided P = .40). Similar results were seen after adjusting for prespecified baseline factors with an observed HR of 1.00 (90% CI, 0.72-1.37) and a 1-sided P value of 0.49.

Objective Response Rate and Duration

Overall 189 patients (96/99, nab-paclitaxel; 93/100, paclitaxel) had measurable disease and were assessed for PFS, PR, and CR; 39 patients (18, nab-paclitaxel; 21, paclitaxel) had a PR; and 5 (3, nab-paclitaxel; 2, paclitaxel) achieved a CR. The RR was 22% for nab-paclitaxel and 25% for paclitaxel (Table 2). No significant difference between treatments was seen, and RR was similar across the levels of each stratification factor. For the 21 patients who responded to nab-paclitaxel, the median duration of response was 4.4 months (95% CI, 3.4-9.4); for the 25 responding patients receiving paclitaxel, median duration of response was 4.3 months (95% CI, 4.2-9.2). Overall, median duration of treatment was 12 weeks; median relative dose intensity was 0.98. More patients receiving nab-paclitaxel (76/97 [78%]) had a relative dose intensity of 90% or more compared with patients receiving paclitaxel (65/97 [67%]). Treatment discontinuation was mostly attributed to disease progression or treatment-related adverse events (AE) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Response Rate in Patients With Measurable Diseasea.

| Variable | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nab-paclitaxel (n = 96) | Paclitaxel (n = 93) | All (n = 189) | |

| Overall response rate | 21 (22) (95% CI, 14%-30%) | 23 (25) (95% CI, 16%-35%) | 44 (23) |

| Best overall response | |||

| Complete response | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (3) |

| Partial response | 18 (19) | 21 (23) | 39 (21) |

| Stable disease | 34 (35) | 30 (32) | 64 (34) |

| Progressive disease | 33 (34) | 31 (34) | 64 (34) |

| Disease control rate | 55 (57) | 53 (57) | 108 (57) |

| Inevaluable | 8 (8) | 9 (10) | 17 (9) |

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) was used for disease assessments.

Safety

Adverse events were as expected: peripheral sensory neuropathy, fatigue, and alopecia (Table 3). There were more grade 3 or higher adverse events with nab-paclitaxel (64/97 [66%] vs 45/97 [46%], P = .009). There were no treatment related-deaths within 30 days of the last dose of nab-paclitaxel; 1 treatment-related death in a patient receiving paclitaxel, and this was related to gastric perforation. Grade 3 or higher neutropenia occurred among 13 of 97 (13%) in those receiving nab-paclitaxel and 7/97 (7%) among those receiving paclitaxel. The grade 3 or higher rates of anemia and thrombocytopenia were less than 10% (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Ten Most Frequently Reported Adverse Events in the nab-Paclitaxel Arm With Corresponding Frequency in the Paclitaxel Arm.

| All grade adverse eventsa | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nab-paclitaxel | Paclitaxel | |||

| All | ≥Gr 3 | All | ≥Gr 3 | |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 72 (74) | 7 (7) | 64 (66) | 3 (3) |

| Fatigue | 71 (73) | 15 (15) | 80 (83) | 12 (12) |

| Alopecia | 62 (64) | 0 | 62 (64) | 0 |

| Constipation | 58 (60) | 2 (2) | 55 (57) | 1 (1) |

| Nausea | 46 (47) | 1 (1) | 44 (45) | 1 (1) |

| Anorexia | 46 (47) | 2 (2) | 44 (45) | 4 (4) |

| Insomnia | 37 (38) | 1 (1) | 24 (25) | 1 (1) |

| Diarrhea | 34 (35) | 4 (4) | 27 (28) | 4 (4) |

| Dyspnea | 31 (32) | 1 (1) | 32 (33) | 1 (1) |

| Arthralgia | 25 (26) | 2 (2) | 26 (27) | 1 (1) |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4) was used to classify adverse events.

nab-Paclitaxel

Most frequently reported adverse events were peripheral sensory neuropathy (72/97 [74.2%]), fatigue (71/97 [73.2%]), and alopecia (62/97 [63.9%]); but were mostly grade 1 or 2. Other adverse events reported in more than 20% of participants were constipation (58/97 [59.8]%), nausea (46/97 [47.4%]), anorexia (46/97 [47.2%]), insomnia (37/97 [38.1%]), diarrhea (34/97 [35.1%]), dyspnea (31/97 [32.0%]), arthralgia (25/97 [25.8%]), vomiting (22/97 [22.7%]), edema (22/97 [22.7%]), urinary tract infection (21/97 [21.6%]), back pain (21/97 [21.6%]), and myalgias (21/97 [21.6%]).

Paclitaxel

Most frequently reported adverse events were fatigue (80/97 [82.5%]), peripheral sensory neuropathy (64/97 [66.0]%), and alopecia (62/97 [64.0%]), which were generally grade 1 or 2. Other adverse events reported by more than 20% of patients were constipation (55/97 [56.7%]), nausea (44/9 [45.4%]), anorexia (44/97 [45.4%]), back pain (34/97 [35.1%]), dyspnea (32/97 [33.0%]), abdominal pain (29/97 [29.9%]), pain in the extremities (28/97 [29.9%]), diarrhea (27/97 [27.8%]), cough (27/97 [27.8%]), arthralgia (26/97 [26.8%]), insomnia (24/97 [24.7%]), edema (22/97 [22.7%]), and myalgias (22/97 [22.7%]).

Quality of Life

Compliance rates for QoL assessments were similar between the arms. Compliance rates were 100% at baseline for both groups but declined quickly to below 70% at cycle 1 of treatment. For each domain/item, the mean (SD) of QoL scores at baseline and mean (SD) of QoL change in scores from baseline, at each assessment time point were calculated. Baseline QoL scores were generally comparable for each domain/item between arms. However, patients receiving nab-paclitaxel had slightly worse scores on fatigue (85 vs 75, P = .06), and insomnia (84 vs 74, P = .05). For the change from baseline at each assessment, there were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in any of the 3 functional domains.

Discussion

In this multicenter randomized phase 2 study, we aimed to demonstrate better efficacy and tolerability of nab-paclitaxel over paclitaxel. Despite encouraging single-arm phase 2 data, the primary objective of this study was not met.9 Nab-paclitaxel did not prolong mPFS compared with paclitaxel—mPFS was 3.35 months with nab-paclitaxel compared with 3.02 months for paclitaxel. Overall mOS was 7.46 months for the nab-paclitaxel group, compared with 8.77 months for the paclitaxel group. Patients with hemoglobin levels lower than 100 g/L did better with paclitaxel compared with nab-paclitaxel (P = .02), possibly owing to better tolerability, though the numbers were too small to draw definitive conclusions.

The mPFS reported here is similar to the chemotherapy arm of contemporary phase 3 trials in the platinum-refractory setting. In the Keynote 045 clinical trial,13 the mPFS for pembrolizumab was 2.1 months vs 3.3 months for chemotherapy; in the IMVIGOR 211 clinical trial,14 the mPFS was 2.1 months for atezolizumab vs 4.0 months for chemotherapy. These results suggest that in the platinum-refractory setting there is a consistent trend toward improved mPFS with chemotherapy compared with immunotherapy. This may be particularly important in patients with rapidly progressive disease.

The ORR for nab-paclitaxel was 21%, which was lower than reported on the single-arm clinical trial, highlighting the importance of randomized clinical trials.9 There are several potential reasons why nab-paclitaxel underperformed. The original trial was a smaller single-arm trial, not stratified, and was conducted at a time when no other treatment options existed; so patient selection and temporal drift may have played a role.9 Our findings are similar to a meta-analysis comparing nab-paclitaxel to solvent-based taxanes in patients with metastatic breast cancer, which showed equivalent response rates and survival rates.15 It is also important to note that the response rates reported here are higher than those in the older taxane studies. This could be owing to differences in baseline patient characteristics, dosing, and supportive care measures between these studies performed many years apart.

The spectrum of AEs seen in this study are generally consistent with taxane-based therapy. However, rates of grade 3 or 4 AEs, specifically peripheral neuropathy, were higher with nab-paclitaxel. This is contrary to what was anticipated, but similar to a meta-analysis15 of 24 trials showing higher rates of peripheral neuropathy with nab-paclitaxel. The exact mechanism underlying this remains unclear, but may be because of increased uptake of drug into neural cells.16 Weekly dosing strategies may be more effective and better tolerated, especially in this patient population.

One of the most important, yet understudied considerations in mUC, is QoL. In this study, the EORTC QLQ C30, EORTC-C15-PAL, and FACT-Taxane scores were incorporated. No differences in the key domains between nab-paclitaxel and paclitaxel were found. To better understand the effects of the disease on QoL in patients with mUC, standard assessments need to be routinely incorporated into ongoing and future clinical trials. Pharmacoeconomics will also play an increasingly important role as the cost of cancer drugs goes up. Because nab-paclitaxel was not superior to paclitaxel, pharmacoeconomic evaluations were deemed noncritical to inform the primary analysis.

As drug development in UC progresses, defining which patients are ideal for which treatment and how best to sequence treatments is an area where both biomarkers and correlative studies will play an important role. In this study, too few patients received prior ICI treatment to inform on optimal sequencing in the second- or third-line setting. Szabados et al17 recently reported that chemotherapy remains active after treatment with ICIs, though larger confirmatory studies are needed. Another emerging question is whether patients can be retreated with drugs used in earlier settings.

Although nab-paclitaxel was not associated with superior PFS compared with paclitaxel as hypothesized, this study confirms the activity of the taxanes, which have a well characterized adverse events profile and are accessible in most jurisdictions. The taxanes are also the main comparator arm of several ongoing phase 3 clinical trials in the platinum-refractory setting exploring fibroblast growth factor (FGFR) inhibitors (NCT03410693) and antibody drug conjugates (NCT03474107); there is also a recently completed study evaluating the combination of nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab in the platinum-refractory setting (NCT03464734).

The landscape of mUC is evolving rapidly but we are yet to find a cure. In the first-line setting, the combination of platinum-based chemotherapy and atezolizumab has shown a PFS benefit over chemotherapy alone.18 In patients with stable disease or response following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, maintenance ICIs have a PFS19 and an OS benefit.20 If the ICIs move into first line, either in combination or as maintenance, there will again be an unmet need in second line and beyond. Both erdafitinib, an FGFR inhibitor and enfortumab, an antibody drug conjugate, have been granted FDA accelerated approval for use after platinum-based chemotherapy and ICI treatment settings, respectively. These drugs, however, are not yet widely available, underscoring the importance of the taxanes, which are relatively well tolerated, effective, and affordable. Whether the taxanes can be used after erdafitinib or enfortumab remains to be seen, but close monitoring, especially for overlapping toxic effects like neuropathy, would be important.

Limitations

Although the dosing schedule (every 21 days) chosen for this study was based on the prior single-arm study and studies in metastatic breast cancer, a weekly dosing schedule, which was not formally evaluated in this study, may be better tolerated, especially in this patient population. Another limitation of this study was the fact that it was conducted before the availability of the ICIs, and so provides very little information about optimal sequencing strategies of treatments in the postplatinum treatment setting. Finally, correlative studies are not yet available to provide molecular insights into why some patients responded to treatment while others did not.

Conclusions

It has been an unprecedented time of drug development in the field of mUC. As our understanding of this disease at the molecular level increases and novel therapeutic strategies begin to enter the treatment paradigm, understanding the optimal drug combinations and sequencing of these new agents will be the next critical step to optimize outcomes for patients with this highly aggressive form of cancer.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Reason for Treatment Discontinuation n (%)

eTable 2. ≥ Grade 3 Hematologic Toxicities in Both Arms

eFigure 1A. Overall Survival in the nab-Paclitaxel and Paclitaxel Arms

eFigure 1B. Overall Survival Forest Plot

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund International London, UK: http://www.wcrf.org. Accessed February 12, 2020.

- 2.Zhou TC, Sankin AI, Porcelli SA, Perlin DS, Schoenberg MP, Zang X. A review of the PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint in bladder cancer: from mediator of immune escape to target for treatment. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(1):14-20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreicer R, Gustin DM, See WA, Williams RD. Paclitaxel in advanced urothelial carcinoma: its role in patients with renal insufficiency and as salvage therapy. J Urol. 1996;156(5):1606-1608. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65459-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, Mazumdar M, et al. Phase II trial of docetaxel in patients with advanced or metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):1853-1857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.5.1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gradishar WJ, Krasnojon D, Cheporov S, et al. Significantly longer progression-free survival with nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3611-3619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.5397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;31(18):1691-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socinski MA, Bondarenko I, Karaseva NA, et al. Weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: final results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2055-2062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. ; IMpassion130 Trial Investigators . Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2108-2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko YJ, Canil CM, Mukherjee SD, et al. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for second-line treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single group, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):769-776. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70162-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan EL and Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958; 53:457–481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1972; 34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719-748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. ; KEYNOTE-045 Investigators . Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1015-1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powles T, Durán I, van der Heijden MS, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):748-757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33297-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Ye G, Yan D, Zhang L, Fan F, Feng J. Role of nab-paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer; a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8(42):72950-72958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo X, Sun H, Dong J, et al. Does nab-paclitaxel have a higher incidence of peripheral neuropathy than solvent-based paclitaxel? Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;139:16-23. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabados B, van Dijk N, Tang YZ, et al. Response rate to chemotherapy after immune checkpoint inhibition in metastatic urothelial cancer. Eur Urol. 2018;73(2):149-152. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grande E, Galsky M, Arranz Arija JA et al. Efficacy and safety from a phase 3 study of Atezolizumab (atezo) as monotherapy or combined with platinum-based chemotherapy (PBC) vs placebo + PBC in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC). Annals of Oncology. 2019;30(Suppl 5). doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz394.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galsky MD, Pal SK, Mortazavi A et al. Randomized double-blind phase II study of maintenance pembrolizumab versus placebo after first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC): HCRN GU14-182. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(Suppl 4504). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bavencio Significantly Improved Overall Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma [press release]. Rockland, Massachusetts and New York, New York: Merck KGaA and Pfizer Inc; January 6, 2020. https://prn.to/36EBko5. Accessed January 6, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Reason for Treatment Discontinuation n (%)

eTable 2. ≥ Grade 3 Hematologic Toxicities in Both Arms

eFigure 1A. Overall Survival in the nab-Paclitaxel and Paclitaxel Arms

eFigure 1B. Overall Survival Forest Plot

Data Sharing Statement