Abstract

This prospective observational study assesses changes in treatment plans for patients with lung cancer and qualifies the types of changes observed as a direct result of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Patients with cancer have higher mortality rates from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),1,2,3,4 particularly those with lung cancer.5 Therefore, efforts are ongoing to limit exposure of these patients to the health care system. As a result, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed cancer care provision, but the extent and type of these changes are unknown. The goal of this study was to evaluate the changes in lung cancer treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We prospectively assessed the treatment plan of all patients seen in the thoracic oncology clinic at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) between March 2 and May 30, 2020. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of either non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Those who had a diagnosis of COVID-19 were excluded. Primary end points were to describe the extent of changes in the treatment plan and qualify the types of changes observed as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Definition of change as a direct result of the pandemic was classified as such according to the patient’s medical record and not inferred. The study was determined to be exempt by the MUHC research ethics board and was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

A total of 289 patients at the thoracic oncology clinic were evaluated; 14 patients were excluded owing to the presence of other tumor histology or owing to COVID-19–positive status. Among the 275 patients included, 211 were receiving active treatment. Among the patients receiving active treatment, 121 (57%) patients experienced at least 1 change in their lung cancer treatment plan. Baseline characteristics are presented in the Table. Among the 238 patients (86.5%) with NSCLC, 172 (62.5%) had advanced disease. Among the 37 patients (13.5%) with SCLC, 11 (4%) had extensive disease.

Table. Baseline Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. | 275 |

| Age, median (range), y | 68 (34-96) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 130 (47.3) |

| Female | 145 (52.7) |

| Cancer type | |

| NSCLC | 238 (52.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 187 (78.5) |

| Squamous | 35 (14.7) |

| NSCLC nonspecified | 16 (6.7) |

| Small cell lung cancer | 37 (13.5) |

| Stage | |

| NSCLC | |

| I | 4 (1.5) |

| II | 17 (6.2) |

| III | 46 (16.7) |

| IV | 172 (62.5) |

| Small cell lung cancer | |

| Limited | 26 (9.5) |

| Extensive | 11 (4.0) |

| Active cancer therapy | |

| No | 64 (23.3) |

| Yes | 211 (76.7) |

| Type of cancer therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 74 (35.1) |

| Targeted | 46 (21.8) |

| Anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy | 67 (31.8) |

| Anti–PD-1/PD-L1/chemotherapy | 34 (16.1) |

| RECIST criteria at time of study | |

| Progressive disease | 53 (19.3) |

| Stable disease | 102 (37.1) |

| Partial response | 38 (13.8) |

| Complete response | 38 (13.8) |

| Not evaluable | 44 (16.0) |

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand-1; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumors.

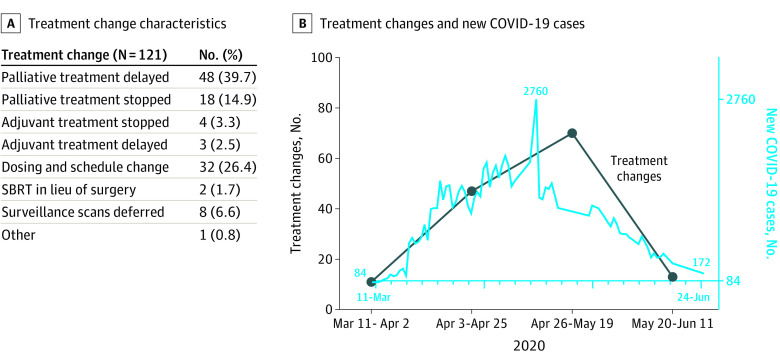

A total of 121 patients (57%) experienced at least 1 change in their lung cancer treatment plan as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 19 patients (9.0%) having more than 1 change. Change characteristics are presented in the Figure. Most changes encompassed delay or cessation of palliative chemotherapy (delay, 48 [39.7%]; cessation, 18 [14.9%]). Mean time-to-resumption of palliative chemotherapy was 36 days, and 4 patients (3%) stopped palliative treatment permanently. Changes in dosing and schedule, which were classified separately from therapeutic delays in treatment, occurred in 32 (26.4%), which included changing pembrolizumab every 6 weeks or durvalumab every 4 weeks. Three patients (2.5%) had delays in adjuvant chemotherapy administration, with a mean delay of 42 days. Lastly, 8 patients (6.6%) experienced deferrals or cancellations of surveillance visits owing to the pandemic. Among patients on active therapy who experienced a treatment change, 2.4% of these changes represented oral targeted agents, 17% represented cytotoxic chemotherapy, 30% represented immunotherapy, and 8% represented combination chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Figure. Characteristics of Treatment Changes for Patients With Lung Cancer During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

COVID-19 indicates coronavirus disease 2019. A. Treatment change characteristics for all patients. B. Treatment changes over time superimposed on new number of COVID-19 cases over time in Canada.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that a considerable proportion (121 [57%]) of patients experienced changes in their lung cancer treatment plan as a direct result of the pandemic. We chose to focus on the lung cancer population owing to their high risk regarding COVID-19, but also because of increasingly favorable therapeutic options, even in the palliative setting. Although changes were observed in the adjuvant and surveillance settings, most changes affected patients who were receiving palliative-intent therapy. Most of the changes occurred between April 26 and May 19, 2020, which represented the peak of the pandemic in Canada.6 Given preliminary findings that active cancer treatment is not associated with increased complications from COVID-19,3 lung cancer treatments and surveillance visits should proceed with caution, and clinicians should proceed with evidence-based care provision in lung cancer. Our study reinforces that all oncology clinics should track these changes occurring in cancer care because it will become important to evaluate the effect of these changes on clinical outcomes.

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(6):783-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. ; COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium . Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907-1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935-941. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC, et al. ; TERAVOLT investigators . COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):914-922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canada Go Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update 2020. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html?topic=tilelink.