This cross-sectional survey study examines whether Black and White men with prostate cancer differ in their willingness to discuss clinical trials with their physicians, and if so, whether patient-level barriers are associated with racial differences.

Key Points

Question

Are Black men with prostate cancer less willing than White men to discuss clinical trials with their physicians, and are patient-level barriers associated with racial differences?

Findings

In this cross-sectional survey study of 205 patients with prostate cancer, most participants reported being willing to discuss trials, but Black men were significantly less willing than White men. Racial differences were associated with greater medical suspicion among Black men.

Meaning

Addressing Black patients’ medical suspicion may promote equity in clinical trial participation.

Abstract

Importance

Black individuals are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials.

Objective

To examine whether Black and White men with prostate cancer differ in their willingness to discuss clinical trials with their physicians and, if so, whether patient-level barriers statistically mediate racial differences.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional survey study used baseline data from Partnering Around Cancer Clinical Trials, a randomized clinical trial to increase Black individuals’ enrollment in prostate cancer clinical trials. Data were collected from 2016 through 2019 at 2 National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer centers; participants were Black and White men with intermediate-risk to high-risk prostate cancer. In mediation analysis, path models regressed willingness onto race and each potential mediator, simultaneously including direct paths from race to each mediator. Significant indirect effect sizes served as evidence for mediation.

Exposures

Race was the primary exposure. Potential mediators included age, education, household income, perceived economic burden, pain/physical limitation, health literacy, general trust in physicians, and group-based medical suspicion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the answer to a single question: “If you were offered a cancer clinical trial, would you be willing to hear more information about it?”

Results

A total of 205 participants were included (92 Black men and 113 White men), with a mean (range) age of 65.7 (45-89) years; 32% had a high school education or lower, and 27.5% had a household income of less than $40 000. Most (88.3%) reported being definitely or probably willing to discuss trials, but White participants were more likely to endorse this highest category of willingness than Black participants (82% vs 64%; χ22 = 8.81; P = .01). Compared with White participants, Black participants were younger (F1,182 = 8.67; P < .001), less educated (F1,182 = 22.79; P < .001), with lower income (F1,182 = 79.59; P < .001), greater perceived economic burden (F1,182 = 42.46; P < .001), lower health literacy (F1,184 = 9.84; P = .002), and greater group-based medical suspicion (F1,184 = 21.48; P < .001). Only group-based medical suspicion significantly mediated the association between race and willingness to discuss trials (indirect effect, −0.22; P = .002).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study of men with prostate cancer, most participants were willing to discuss trials, but Black men were significantly less willing than White men. Black men were more likely to believe that members of their racial group should be suspicious of the health care system, and this belief was associated with lower willingness to discuss trials. Addressing medical mistrust may improve equity in clinical research.

Introduction

Black people are disproportionately affected by cancer incidence and mortality yet underrepresented in cancer clinical trials.1,2 Black individuals may be less willing to participate in trials owing to barriers that disproportionately affect this group, such as low health literacy, financial burden, mistrust in clinicians, and group-based medical suspicion (ie, belief that members of one’s racial group should be suspicious of the health care system).3,4 However, minorities who are eligible and invited to participate in a trial are as likely to enroll as White patients, suggesting that enrollment disparities may stem from clinician-level or system-level factors, such as restrictive eligibility criteria or physicians’ reluctance to discuss trials with Black patients.3,5,6

This cross-sectional exploratory analysis reports patient baseline data from the first phase of Partnering Around Cancer Clinical Trials (PACCT),6 a randomized clinical trial of a communication intervention to increase Black men’s participation in prostate cancer clinical trials. The current study examines (1) whether Black men are less willing to discuss clinical trials than White men and (2) potential mediating roles of other sociodemographic characteristics, financial burden, health literacy, pain/physical limitation, general trust in clinicians, and group-based medical suspicion.

Methods

Participants, Setting, and Procedures

Data were collected from November 2016 through January 2019 at Karmanos Cancer Institute (KCI) and Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center (SKCCC). Procedures were approved by sites’ institutional review boards, and participants provided written informed consent. Eligible patients (n = 205) had intermediate-risk to high-risk prostate cancer and self-identified as Black/Black or White. This study examines PACCT patient participants’ baseline data, collected at enrollment. Complete PACCT procedures are available elsewhere.6

Measures

One item measured willingness to discuss clinical trials, “If you were offered a cancer clinical trial, would you be willing to hear more information about it?” (1 = definitely not; 5 = definitely yes).7

Patients reported sociodemographic characteristics (race, age, education, household income), perceived economic burden (3 items; α = .86),8 pain/physical limitation (4 items; α = .76),9 health literacy (3 items; α = .74),10 general trust in physicians (5 items; α = .80),11 and group-based medical suspicion (6-item subscale of the Group Based Medical Mistrust Scale; α = .88).12

Data Preparation and Analysis

Three participants indicated being unwilling to discuss clinical trials. We excluded these outliers and conducted analyses with the remaining categorical responses (unsure, probably yes, definitely yes). A χ2 test of associations tested whether there were significant racial differences in willingness.

Two full factorial 2 (race) by 2 (site) multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) tested racial differences in potential mediators, accounting for site. The first included age, education, income, and perceived economic burden as correlated outcomes; the second included pain/physical limitation, health literacy, general trust in physicians, and group-based medical suspicion. The MANOVAs indicated significant main effects of race and site on the first (Wilks λ = 0.66; F4,179 = 23.12; P < .001; Wilks λ = 0.89; F4,189 = 5.53; P < .001, respectively) and second linear combinations (Wilks λ = 0.87; F4,181 = 6.72; P < .001; Wilks λ = 0.95; F4,181 = 2.53; P = .04, respectively), but no significant race by site interaction for either (Wilks λ = 0.97; F4,179 = 1.10; P = .36; Wilks λ = 0.99; F4,181 = 0.69; P = .60). Univariate ANOVAs clarified associations between race and potential mediators.

We used ordered probit to model the willingness outcome via path models with lavaan using R, version 3.6.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Path models regressed willingness onto race and onto each potential mediator, simultaneously including direct paths from race to each mediator. Statistically significant indirect effect sizes provide evidence for mediation. We first fit a path model including all mediators that differed by race in ANOVAs described above, followed by a trimmed model excluding mediators if the indirect effect was nonsignificant (P > .05), controlling for site. Sample size was determined based on power analyses for PACCT intervention outcomes; current analyses were sufficiently powered.6

A sensitivity analysis included outliers and participants who were missing responses to the outcome measure (perhaps indicating passive refusal to discuss trials) as “unsure” of their willingness to discuss clinical trials. Results did not differ from those reported below.

Results

Participants were Black (n = 92) and White (n = 113) men of mean (range) age of 65.7 (45-89) years. Participants were well distributed across education and income levels (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics by Race.

| Variable | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 205) | White men (n = 113) | Black men (n = 92) | |

| Site | |||

| KCI | 110 (53.7) | 53 (46.9) | 57 (62.0) |

| SKCCC | 95 (46.3) | 60 (53.1) | 35 (38.0) |

| Age, mean (range), y | 65.7 (45-89) | 66.9 (47-89) | 64.2 (45-89) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 66 (32.2) | 23 (20.4) | 43 (46.7) |

| Some college or 2-y degree | 43 (21.0) | 20 (17.7) | 23 (25.0) |

| College degree | 37 (18.0) | 23 (20.4) | 14 (15.2) |

| Graduate/professional | 59 (28.8) | 47 (41.6) | 12 (13.0) |

| Household income, $ | |||

| <20 000 | 37 (18.0) | 2 (1.8) | 35 (38.0) |

| 20 000-39 999 | 20 (9.8) | 7 (6.2) | 13 (14.1) |

| 40 000-59 999 | 30 (14.6) | 16 (14.2) | 14 (15.2) |

| 60 000-79 999 | 22 (10.7) | 12 (10.6) | 10 (10.9) |

| ≥80 000 | 86 (42.0) | 71 (62.8) | 15 (16.3) |

| Missing | 10 (4.9) | 5 (4.4) | 5 (5.4) |

| Economic burden (4-point scale), mean (SD) | 1.66 (0.82) | 1.34 (0.52) | 2.06 (0.94) |

| Pain/physical limitation (4-point scale), mean (SD) | 1.54 (0.53) | 1.49 (0.46) | 1.61 (0.60) |

| Health literacy (5-point scale), mean (SD) | 4.02 (0.99) | 4.27 (0.81) | 3.72 (1.12) |

| General trust in physicians (5-point scale), mean (SD) | 3.58 (0.75) | 3.63 (0.75) | 3.52 (0.75) |

| Group-based medical suspicion (5-point scale), mean (SD) | 1.87 (0.70) | 1.67 (0.62) | 2.14 (0.72) |

| Willing to discuss clinical trials | |||

| Definitely not | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (2.2) |

| Probably not | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Unsure | 15 (7.3) | 5 (4.4) | 10 (10.9) |

| Probably yes | 36 (17.6) | 15 (13.3) | 21 (22.8) |

| Definitely yes | 145 (70.7) | 91 (80.5) | 54 (58.7) |

| Missing | 6 (2.9) | 2 (1,8) | 4 (8.7) |

Abbreviations: KCI, Karmanos Cancer Institute; SKCCC, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Racial Differences in Willingness

White participants were more likely to be definitely willing to discuss clinical trials than Black participants (82% vs 64%; χ22 = 8.81; P = .01). There were no differences in endorsement of other categories.

Racial Differences in Potential Mediators

Univariate ANOVAs following the 2 MANOVAs described above indicated that Black participants were younger, less educated, had lower income, and greater perceived economic burden (Fs1,182 ranged from 8.67-79.59; P < .01 for all), as well as lower health literacy (F1,184 = 9.84; P = .002) and greater group-based medical suspicion (F1,184 = 21.48; P < .001); eTable in the Supplement). Because there were no significant racial differences in pain/physical limitation or general trust in physicians, these were excluded from path analysis.

Path Analysis

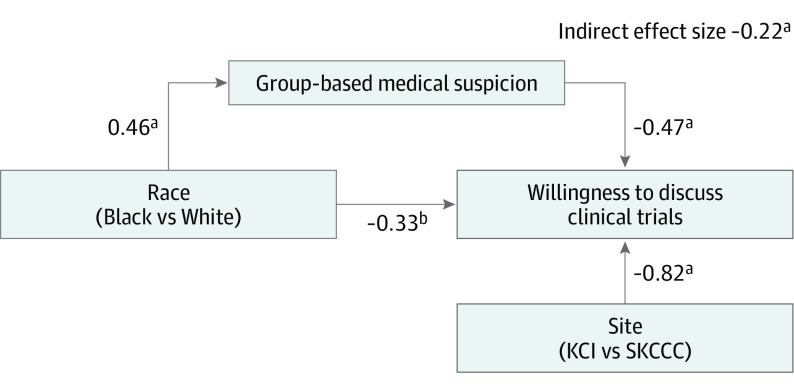

Results of the untrimmed model indicated that only group-based medical suspicion significantly mediated the association between race and willingness to discuss clinical trials (Table 2). The trimmed model, including only race, site, and group-based medical suspicion, exhibited good fit (model χ21 = 1.67; P > .05; comparative fit index, 0.95; Tucker-Lewis index, 0.95; root mean square error of approximation, 0.06). Black participants reported greater medical suspicion, which, in turn, was associated with lower willingness to discuss clinical trials (indirect effect size, −0.22; P = .002; Figure).

Table 2. Full and Trimmed Path Model Results.

| Full model | Trimmed model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | P value | Estimate (SE) | P value | |

| Regression parameters | ||||

| Willingness | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | −0.58 (0.33) | .08 | −0.33 (0.20) | .09 |

| Site (reference: SKCCC) | −0.74 (0.23) | .001 | −0.82 (0.22) | <.001 |

| Age | −0.02 (0.01) | .04 | NA | NA |

| Education | 0.08 (0.06) | .21 | NA | NA |

| Income | −0.06 (0.08) | .48 | NA | NA |

| Economic burden | 0.14 (0.13) | .29 | NA | NA |

| Health literacy | 0.02 (0.10) | .81 | NA | NA |

| Suspicion | −0.40 (0.13) | .001 | −0.47 (0.11) | <.001 |

| Age | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | −3.06 (1.21) | .011 | NA | NA |

| Education | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | −1.25 (0.29) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| Income | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | −1.69 (0.23) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| Economic burden | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | 0.71 (0.12) | <.001 | NA | NA |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Race (reference: White) | −0.47 (0.15) | .001 | NA | NA |

| Suspicion | ||||

| Race (refence: White) | 0.49 (0.10) | <.001 | 0.46 (0.10) | <.001 |

| R2 | ||||

| Willingness | 0.31 | NA | 0.29 | NA |

| Age | 0.04 | NA | NA | NA |

| Education | 0.13 | NA | NA | NA |

| Income | 0.32 | NA | NA | NA |

| Economic burden | 0.20 | NA | NA | NA |

| Health literacy | 0.06 | NA | NA | NA |

| Suspicion | 0.12 | NA | 0.11 | NA |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Race*age | 0.07 (0.04) | .11 | NA | NA |

| Race*education | −0.09 (0.08) | .23 | NA | NA |

| Race*income | 0.10 (0.14) | .48 | NA | NA |

| Race*economic burden | 0.10 (0.10) | .30 | NA | NA |

| Race*health literacy | −0.01 (0.05) | .81 | NA | NA |

| Race*suspicion | −0.20 (0.07) | .007 | −0.22 (0.07) | .002 |

Abbreviations: KCI, Karmanos Cancer Institute; NA, not applicable; SKCCC, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Figure. Trimmed Path Model.

Graphic representation of the trimmed path model, in which group-based medical suspicion significantly mediates the association between race and willingness to discuss clinical trials.

aP < .001.

bP = .09.

Discussion

Of more than 200 Black and White men with intermediate-risk to high-risk prostate cancer, 88.3% were willing to discuss clinical trials with their physicians. However, Black men were significantly less willing than White men. Black men were more likely than White men to believe that members of their racial group should be suspicious of the health care system, and this suspicion was associated with lower willingness to discuss clinical trials. This finding is consistent with work highlighting medical suspicion as a barrier to minority accrual in clinical trials.4 However, past work has also shown that Black and White men are equally likely to enroll in clinical trials if given the opportunity.3 One possibility is that clinicians are less likely to discuss trials with Black patients they perceive as more suspicious. Importantly, most Black individuals in this sample reported being willing to discuss trials, suggesting that clinicians may find higher acceptance than they expect.

Limitations

One limitation of this research is that while patient willingness likely affects whether trials are discussed, disparities in clinical trial enrollment may accrue at several steps between trial discussion and actual participation, including trial availability, eligibility criteria, and patient access. Also, patients in our sample had a potentially life-threatening cancer diagnosis, had access to care in academic medical centers where trials are offered, and had agreed to participate in this study. Patients with these characteristics or circumstances may report being more willing to discuss clinical trials than is true of the general population. Furthermore, high willingness to discuss clinical trials in this sample may have limited our ability to detect significant mediating associations. A useful direction for future research is to examine willingness to discuss clinical trials among groups of patients for whom there is likely to be greater variability.

Conclusions

Increasing trustworthiness of clinical trial research and earning Black patients’ trust may promote equity in clinical trial participation. At the system level, engaging community members in research and increasing transparency around research practices will likely contribute to greater equity in enrollment.13,14 Clinicians can enhance communication skills to initiate trial discussions with Black patients, address patients’ concerns, and discuss potential benefits and risks of participation.15 These efforts will help ensure that all patients have access to the best available prostate cancer treatments and that the knowledge accumulated in clinical trials is generalizable to a diverse patient population.

eTable. MANOVA Results

References

- 1.Chen MS Jr, Lara PN, Dang JH, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2014;120(suppl 7):1091-1096. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. . Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;e191870. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langford AT, Resnicow K, Dimond EP, et al. . Racial/ethnic differences in clinical trial enrollment, refusal rates, ineligibility, and reasons for decline among patients at sites in the National Cancer Institute’s Community Cancer Centers Program. Cancer. 2014;120(6):877-884. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A. The role of clinical trial participation in cancer research: barriers, evidence, and strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:185-198. doi: 10.14694/EDBK_156686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. . Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3(2):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggly S, Hamel LM, Heath E, et al. . Partnering around cancer clinical trials (PACCT): study protocol for a randomized trial of a patient and physician communication intervention to increase minority accrual to prostate cancer clinical trials. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):807. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3804-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen PB, Wells KJ, Meade CD, et al. . Effects of a brief multimedia psychoeducational intervention on the attitudes and interest of patients with cancer regarding clinical trial participation: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2516-2521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, et al. . Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: another long-term effect of cancer? Cancer. 2015;121(8):1257-1264. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson T, Sizmur S, Whatling J, Arikan S, McDonald D, Ingram D. Evaluation of a new short generic measure of health status: howRu. Inform Prim Care. 2010;18(2):89-101. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v18i2.758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz KL, Bartoces M, Campbell-Voytal K, et al. . Estimating health literacy in family medicine clinics in metropolitan Detroit: a MetroNet study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):566-570. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.130052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):209-218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks SE, Muller CY, Robinson W, et al. . Increasing minority enrollment onto clinical trials: practical strategies and challenges emerge from the NRG Oncology Accrual Workshop. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(6):486-490. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.005934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkins CH, Mapes BM, Jerome RN, Villalta-Gil V, Pulley JM, Harris PA. Understanding what information is valued by research participants, and why. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):399-407. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Heath E, Gwede CK, Eggly S. Barriers to clinical trial enrollment in racial and ethnic minority patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):327-337. doi: 10.1177/107327481602300404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. MANOVA Results