Key Points

Question

Is adjuvant chemotherapy associated with survival in patients with node-negative, early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with vs without high-risk clinicopathologic features?

Findings

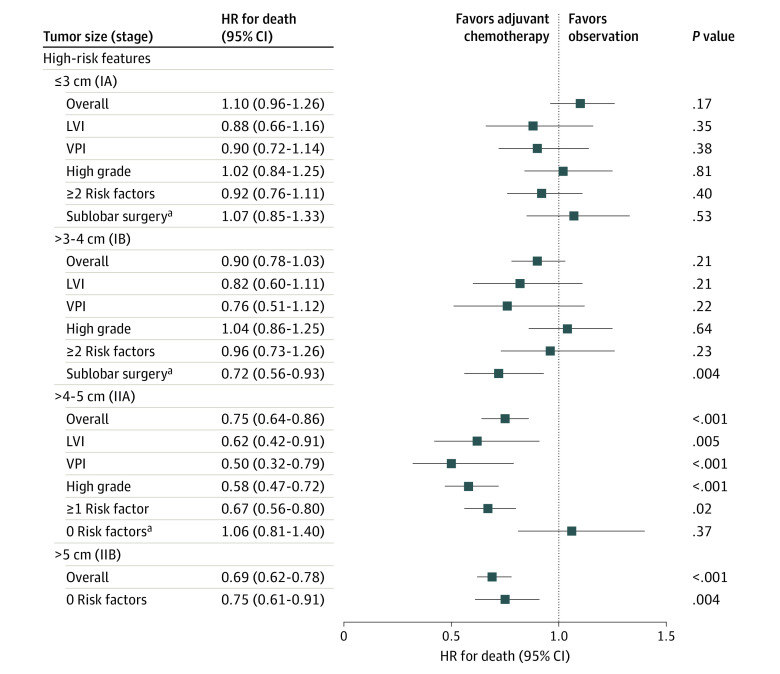

In this cohort study of 50 814 patients with NSCLC, adjuvant chemotherapy use was associated with a survival benefit if the tumor was larger than 3 to 4 cm and sublobar resection was performed, the tumor was larger than 4 to 5 cm and at least 1 high-risk pathologic feature was present, or the tumor was larger than 5 cm irrespective of high-risk pathologic features.

Meaning

The findings suggest that high-risk pathologic features, extent of resection, and tumor size should be simultaneously considered when evaluating patients with early-stage NSCLC for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Abstract

Importance

Tumor size larger than 4 cm is accepted as an indication for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Treatment guidelines suggest that high-risk features are also associated with the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with early-stage NSCLC, yet this association is understudied.

Objective

To assess the association between adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in the presence and absence of high-risk pathologic features in patients with node-negative early-stage NSCLC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study using data from the National Cancer Database included 50 814 treatment-naive patients with a completely resected node-negative NSCLC diagnosed between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2015. The study was limited to patients who survived at least 6 weeks after surgery (ie, estimated median time to initiate adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery) to mitigate immortal time bias. Statistical analysis was performed from December 1, 2018, to February 29, 2020.

Exposures

Adjuvant chemotherapy use vs observation, stratified according to the presence or absence of high-risk pathologic features (visceral pleural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and high-grade histologic findings), sublobar surgery, and tumor size.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The association of high-risk pathologic features with survival after adjuvant chemotherapy vs observation was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Results

Overall, 50 814 eligible patients with NSCLC (27 365 women [53.9%]; mean [SD] age, 67.4 [9.5] years]) were identified, including 4220 (8.3%) who received adjuvant chemotherapy and 46 594 (91.7%) who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Among patients with tumors 3 cm or smaller, chemotherapy was not associated with improved survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.10; 95% CI, 0.96-1.26; P = .17). For patients with tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a survival benefit among patients who underwent sublobar surgery (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.56-0.93; P = .004). For tumors larger than 4 cm to 5 cm, a survival benefit was associated with adjuvant chemotherapy only in patients with at least 1 high-risk pathologic feature (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.80; P = .02). For tumors larger than 5 cm, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a survival benefit irrespective of the presence of high-risk pathologic features (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.91; P = .004).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, tumor size alone was not associated with improved efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage (node-negative) NSCLC. High-risk clinicopathologic features and tumor size should be considered simultaneously when evaluating patients with early-stage NSCLC for adjuvant chemotherapy.

This cohort study uses data from the National Cancer Database to assess the association between adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in patients with node-negative early-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with vs without high-risk pathologic features.

Introduction

Lung cancer represents a significant global health problem, accounting for more than 1.7 million deaths worldwide in 2018.1 Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can take a particularly aggressive course, and even patients with early-stage NSCLC are at risk of death.2,3 Complete surgical resection, historically associated with the highest cure rates with locoregionally confined tumors, may not suffice for some patients with NSCLC.2 More specifically, up to 30% of patients with stage I NSCLC will die within 5 years of surgery.3 As a result, there has been considerable effort to identify patients with early-stage NSCLC who may benefit from additional treatment after surgery.

The addition of adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection has demonstrated a survival advantage in several subsets of patients with NSCLC, including those with node-positive disease.4,5,6,7,8 Multiple randomized clinical trials have attempted to define a role for adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery for node-negative, early-stage lung cancer but have been unsuccessful.9,10 The unplanned subset analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9633, however, observed an association of improved survival with adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with tumors 4 cm or larger.11 Since that time, tumor size has become a common criterion for the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative NSCLC.12,13,14 More recently, several high-risk histopathologic features (eg, visceral pleural invasion [VPI], lymphovascular invasion [LVI], and high-grade histologic findings) and treatment factors such as the use of sublobar resection have been proposed as potential independent indications for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC.14 However, there are few data to support these recommendations.

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a comprehensive data resource that captures the care of approximately 70% of newly diagnosed patients with NSCLC in the US.15 Using data from the NCDB, we assessed the association of adjuvant chemotherapy with survival in patients with early-stage NSCLC stratified by tumor size, high-risk features, and resection type.

Methods

Data Source

This cohort study used data from the NCDB, a hospital-based tumor registry jointly managed by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.16 The Yale University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent because data were deidentified.

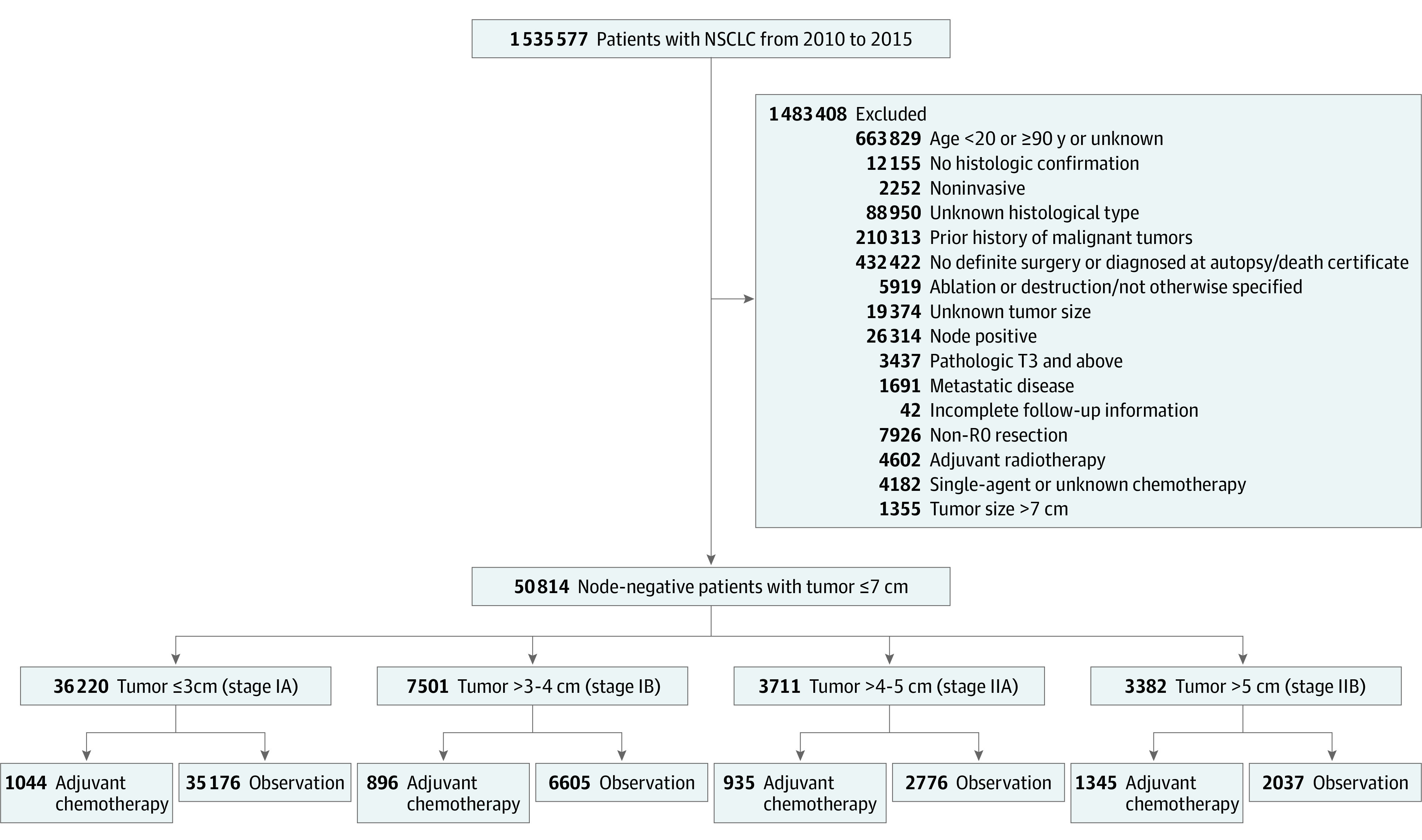

Study Population

A query of the NCDB Participant User File from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2015 (data on VPI and LVI were not collected for cases diagnosed before 2010), was performed for treatment-naive patients 20 years or older with completely resected (R0, negative margins) invasive NSCLC. Only patients with lymph node–negative tumors with complete pathologic staging and pathologic T1 and T2 stages (ie, without locoregional invasion or satellite tumor nodules) for whom the diagnosis of NSCLC represented their first malignant neoplasm were included. Among patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, only those who received multiagent chemotherapy were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of the Primary Study Cohort Selection Steps.

NSCLC indicates non–small cell lung cancer.

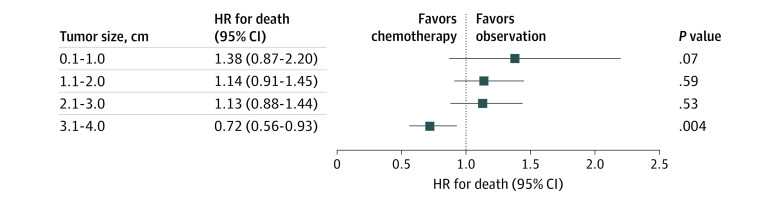

Sublobar resection (wedge resection and segmentectomy) is listed as a high-risk feature and indicator for adjuvant chemotherapy by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.14 However, the population in the primary study cohort who underwent sublobar resection was small (n = 8220). To increase study power, an extended cohort was created over a longer time frame (2004-2015). The frequency of sublobar resection was low in patients with tumors larger than 4 cm, which likely reflects the challenge and potential compromise of margins by taking less lung parenchyma in this context. Therefore, this secondary analysis was limited to tumors that were 4 cm or smaller.

Data Elements

The following high-risk pathologic features were selected in accordance with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines14: VPI, LVI, and high-risk histologic findings (high grade or undifferentiated). Sublobar resection was defined as wedge resection and nonanatomic segmentectomy. Other independent variables included the following: age; sex; race/ethnicity; insurance status; median household income; educational level; area of residence; distance from facility; facility type and location; Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index score; year of diagnosis; tumor primary site, laterality, histologic type, and size; and type of surgical resection.17 Cohorts were stratified by 1-cm tumor size initially but presented as the following to reflect guideline recommendations and current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual 8th edition18 staging nomenclature and for simplicity: stage IA, 3 cm or less; stage IB, greater than 3 to 4 cm; stage IIA, greater than 4 to 5 cm; and stage IIB, greater than 5 to 7 cm. No restriction was applied with regard to the interval between surgery and receipt of chemotherapy (>95% patients received adjuvant chemotherapy within 12 weeks after surgery). More important, within the comparison group (observation without chemotherapy), patients for whom chemotherapy was not recommended or administered because it was contraindicated owing to patient risk factors were excluded.

For the primary analyses, disease stage was captured in accordance with the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th edition.19 For the secondary analysis of sublobar resection, the study set was expanded to include 2004 to 2015, which spanned the transition from the 6th edition to the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual lung cancer staging system, reflected in the NCDB starting in 2010. Because information on patients coded before 2010 did not contain sufficient staging data for conversion to the staging criteria of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th edition, a homogenous study group was created by converting patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2015 to the corresponding 6th edition disease stage to mitigate the transition between stages. Because there were no changes in the staging nomenclature from 2010 to 2015, no corrective measures were necessary for the analysis of the primary cohort.

The primary outcome included overall survival (OS), which was assessed from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up. A sensitivity analysis was performed examining OS from the date of diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from December 1, 2018, to February 29, 2020. Bivariate analyses were performed using the χ2 test for categorical variables (or Fisher exact test when appropriate) and the t test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to provide estimates for OS.

Missing Data Strategy

Multiple imputation via chained equations was used to address missing data.20 Review of the patterns of missing data did not identify any indication that data were not missing at random. We attempted to account for all variables that might be associated with missing data for covariates of interest in our multiple imputation model and achieved similar results for our Cox proportional hazards regression models using complete cases and multiple imputation analyses.20 The Rubin rules were used to generate pooled effect estimates and variance across imputed data sets.21

Survival Analysis

The survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-risk features was assessed using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models. These models included all relevant variables (age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, income, educational level, area of residence, distance from facility, facility type and location, tumor primary site, histologic type, type of resection, and Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index score) and a hospital-specific random effect to account for hospital-level clustering (Table).22,23 Age and distance were modeled as continuous variables. To mitigate the effects of improvement in health care and other changes during the study period, we included year of diagnosis in all the Cox proportional hazards regression models. Visual inspections of log-log plots of the survival functions were performed to ensure proportionality assumptions.24 The study was landmarked at 6 weeks, meaning only patients who survived at least 6 weeks were included (median time to adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery), to mitigate immortal time bias.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy vs Observation for Node-Negative Tumors of 7 cm or Smaller.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%)a | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation (n = 46 594) | Adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 4220) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 68 (62-75) | 64 (57-70) | <.001 |

| Age category, y | |||

| <65 | 15 789 (33.9) | 2145 (50.8) | <.001 |

| 65-74 | 19 014 (40.1) | 1681 (39.8) | |

| ≥75 | 11 791 (25.1) | 394 (9.3) | |

| Male | 21 357 (45.4) | 2092 (49.6) | <.001 |

| White race | 40 753 (87.5) | 3675 (87.1) | .48 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 43 804 (94.0) | 3984 (94.4) | .53 |

| Hispanic | 1221 (2.6) | 107 (2.5) | |

| Unknown | 1569 (3.4) | 129 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Not insured | 867 (1.9) | 110 (2.6) | <.001 |

| Private insurance | 13 020 (27.9) | 1675 (39.7) | |

| Medicaid | 2370 (5.1) | 294 (7.0) | |

| Medicare | 29 313 (62.9) | 2035 (48.2) | |

| Other government insurance | 498 (1.1) | 54 (1.3) | |

| Unknown | 526 (1.1) | 52 (1.2) | |

| Facility type | |||

| Nonacademicb | 30 608 (65.7) | 2848 (67.5) | .02 |

| Academic | 15 986 (34.3) | 1372 (32.5) | |

| Facility location | |||

| Northeast | 9332 (20.0) | 868 (20.6) | .001 |

| Midwest | 12 252 (26.3) | 1131 (26.8) | |

| South | 19 262 (41.3) | 1794 (42.5) | |

| West | 5748 (12.3) | 427 (10.1) | |

| Area of residencec | |||

| Rural | 982 (2.1) | 109 (2.6) | .01 |

| Urban | 7238 (15.5) | 692 (16.4) | |

| Metropolitan | 37 246 (79.9) | 3339 (79.1) | |

| Unknown | 1128 (2.4) | 80 (1.9) | |

| Distance from facility, km | |||

| ≤16.1 | 21 556 (46.3) | 1974 (46.8) | <.001 |

| 16.2-32.2 | 9733 (20.9) | 889 (21.1) | |

| 32.3-80.5 | 9704 (20.8) | 934 (22.1) | |

| 80.6-161.0 | 3731 (8.0) | 316 (7.5) | |

| >162.0 | 1870 (4.0) | 107 (2.5) | |

| Median annual income, $ | |||

| <38 000 | 8583 (18.4) | 810 (19.2) | .06 |

| 38 000-47 999 | 11 506 (24.7) | 1083 (25.7) | |

| 48 000-62 999 | 12 497 (26.8) | 1143 (27.1) | |

| >63 000 | 13 910 (29.9) | 1179 (27.9) | |

| Unknown | 98 (0.2) | NRd | |

| Educational level, %e | |||

| ≥21 | 7907 (17.0) | 731 (17.3) | .06 |

| 13-20.9 | 12 989 (27.9) | 1229 (29.1) | |

| 7-12.9 | 15 641 (33.6) | 1418 (33.6) | |

| <7 | 9977 (21.4) | 839 (19.9) | |

| Unknown | 80 (0.2) | NRd | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2010 | 6901 (14.8) | 646 (15.3) | .07 |

| 2011 | 7344 (15.8) | 605 (14.3) | |

| 2012 | 7370 (15.8) | 705 (16.7) | |

| 2013 | 7925 (17.0) | 688 (16.3) | |

| 2014 | 8288 (17.8) | 746 (17.7) | |

| 2015 | 8766 (18.8) | 830 (19.7) | |

| Histologic type | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 29 653 (63.6) | 2332 (55.3) | <.001 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 14 963 (32.1) | 1502 (35.6) | |

| Large cell | 923 (2.0) | 247 (5.9) | |

| Otherf | 1055 (2.3) | 139 (3.3) | |

| Laterality | |||

| Unknown | 124 (0.3) | 28 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Right | 27 795 (59.7) | 2529 (59.9) | |

| Left | 18 675 (40.1) | 1663 (39.4) | |

| Primary site | |||

| Main bronchus | 102 (0.2) | 23 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Lobe | |||

| Upper | 28 259 (60.7) | 2516 (59.6) | |

| Middle | 2320 (5.0) | 200 (4.7) | |

| Lower | 15 000 (32.2) | 1343 (31.8) | |

| Overlapping lesion | 340 (0.7) | 79 (1.9) | |

| Lung, NOS | 573 (1.2) | 59 (1.4) | |

| VPI | |||

| Absent | 33 737 (72.4) | 3159 (74.9) | <.001 |

| Present | 4578 (9.8) | 794 (18.8) | |

| Unknown | 9143 (19.6) | 267 (6.3) | |

| LVI | |||

| Absent | 37 660 (80.8) | 3075 (72.9) | <.001 |

| Present | 5715 (12.3) | 858 (20.3) | |

| Unknown | 3219 (6.9) | 287 (6.8) | |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 7798 (16.7) | 262 (6.2) | <.001 |

| Moderately differentiated | 19 433 (41.7) | 1278 (30.3) | |

| Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | 17 253 (37.0) | 2447 (58.0) | |

| Unknown | 2110 (4.5) | 233 (5.5) | |

| Surgical resection | |||

| Sublobar resection | 7921 (17.0) | 299 (7.1) | <.001 |

| Lobectomy | 38 123 (81.8) | 3735 (88.5) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 550 (1.2) | 186 (4.4) | |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index score | |||

| 0 | 21 981 (47.2) | 2214 (52.5) | <.001 |

| 1 | 16 475 (35.4) | 1412 (33.5) | |

| ≥2 | 8138 (17.5) | 594 (14.1) | |

| Length of stay after surgery, wk | |||

| ≤2 | 41 477 (89.0) | 3713 (88.0) | <.001 |

| >2 | 2609 (5.6) | 158 (3.7) | |

| Unknown | 2508 (5.4) | 349 (8.3) | |

| Readmission within 30 d after discharge | |||

| No | 42 927 (92.1) | 3552 (84.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1919 (4.1) | 136 (3.2) | |

| Unknown | 1748 (3.8) | 532 (12.6) | |

| Died within 90 d after surgery | |||

| No | 45 417 (97.5) | 4145 (98.2) | .007 |

| Yes | 502 (1.1) | 27 (0.6) | |

| Unknown | 675 (1.5) | 48 (1.1) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; NOS, not otherwise specified; NR, not reported; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; VPI, visceral pleural invasion.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated. Percentages might not total 100% owing to approximation.

Includes community cancer program, comprehensive community cancer program, integrated network cancer program, and other specified types of cancer programs.

Based on patient’s zip code area.

Frequencies less than 10 not reported per National Cancer Database guidelines.

Percent of people in the patient’s zip code area with no high-school diploma.

Non–small cell cancer not further defined.

To minimize the potential of spurious treatment-effect findings owing to large imbalances in risk factors, we used inverse propensity score weighting25 in which the propensity score was the conditional probability of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy vs observation given a vector of covariates. The propensity score was created using logistic regression and included all relevant clinicopathologic and sociodemographic variables. The weights for adjuvant chemotherapy cases were defined as 1/propensity score. The covariate balance after propensity score weighting was checked by comparing raw and weighted standardized differences (eTables 1-4 in the Supplement).

Because the proportion of patients with small tumors (<3 cm) was small, we performed a supplementary analysis in this group in which we included all significant interactions between treatment and patient covariates. This analysis allowed us to assess whether there was any heterogeneity of effect across patient subgroups.

All tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Among the 50 814 patients (27 365 women [53.9%]; mean [SD] age, 67.4 [9.5] years) who met the initial inclusion criteria, 4220 (8.3%) received adjuvant chemotherapy and 46 594 (91.7%) were treated with observation alone (Figure 1). Patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy were younger than those undergoing observation (median age, 64 [interquartile range, 57-70 years] vs 68 years [interquartile range, 62-75 years]; P < .001), more likely to have private insurance (1675 [39.7%] vs 13 020 [27.9%]; P < .001), more likely to have high-grade histologic features (2447 [58.0%] vs 17 253 [37.0%]; P < .001), and less likely to be readmitted within the first 30 days after admission for surgical resection (136 [3.2%] vs 1919 [4.1%]; P < .001) (Table).

Association of Chemotherapy With Survival Based on Tumor Size and High-Risk Features

Tumor Size of 3 cm or Less

Among patients with tumors 3 cm or less, chemotherapy was not associated with improved survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.10; 95% CI, 0.96-1.26; P = .17). The lack of association persisted irrespective of the presence of high-risk pathologic features or sublobar resection (Figure 2 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Inverse propensity score–weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models and sensitivity analyses examining interactions also showed similar results (eTables 1 and 6 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Association of Survival With Adjuvant Chemotherapy Based on the Presence of High-Risk Pathologic Features or Sublobar Resection in Patients Stratified by the 4 Tumor Size Categories or Stages.

Overall refers to all comers in the size category irrespective of high-risk features; high-grade indicates poor differentiation or undifferentiated. HR indicates hazard ratio; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; and VPI, visceral pleural invasion.

aFor sublobar surgery, a larger cohort from 2004 to 2015 was used to increase power.

In the secondary analysis to evaluate the association of chemotherapy after sublobar resection with survival, the extended study set including patients with smaller tumors (≤3 cm) was examined (ie, 2004-2015). In patients with tumors 3 cm or less managed by sublobar resection, adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with improved survival (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.85-1.33; P = .53) (Figure 3 and eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Association of Survival With Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Tumors 4 cm or Smaller Who Underwent Sublobar Resection.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

Tumors Larger Than 3 cm to 4 cm

Among patients with tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm and VPI, LVI, or high-grade histologic findings, adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with an increase in survival (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.78-1.03; P = .21). Among patients with 2 or more high-risk features, no significant increase in survival was associated with adjuvant chemotherapy (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.73-1.26; P = .23) (Figure 2). Inverse propensity score–weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models showed similar results. A survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy for tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm was seen in a subset of patients who had undergone sublobar resection, but the analysis was potentially underpowered (only 57 patients who underwent sublobar resection had received chemotherapy) in the primary cohort.

In the extended cohort, sublobar resection was performed in 1172 patients, including 145 (12.4%) who received adjuvant chemotherapy. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis demonstrated survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy compared with observation (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.56-0.93; P = .004) (Figure 3).

Tumors Larger Than 4 cm to 5 cm

In patients with tumors larger than 4 cm to 5 cm and at least 1 high-risk factor, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant survival benefit (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.80; P = .02). However, in the absence of these high-risk features in patients with tumors larger than 4 cm to 5 cm (1654 of 3711 in the cohort with tumors larger than 4-5 cm [44.6%]), adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with improved survival.

Tumors Larger Than 5 cm to 7 cm

In all patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with significant survival benefit (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.91; P = .004), which was also seen in the inverse propensity score–weighted multivariable models. This association was seen even in the absence of any pathologic high-risk features. Sensitivity analyses performed examining OS from the date of diagnosis (instead of OS from the date of surgery) showed similar results in all categories (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our objective was to evaluate the association between adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in patients with node-negative, early-stage NSCLC stratified by high-risk clinicopathologic features and tumor size. We found that the association of adjuvant chemotherapy with survival benefit was strongest when tumor size, high-risk features, and perhaps the extent of resection were simultaneously considered in this cohort with node-negative disease.

The association between the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy and several individual tumor attributes has been examined previously.26,27 Platinum-based chemotherapy has been demonstrated to be associated with survival benefit when used after surgical resection for patients with node-positive tumors.4 In patients with node-negative NSCLC, to our knowledge, only tumor size has been well studied as a factor associated with survival after adjuvant chemotherapy. Because the unplanned subset analysis of CALGB 9633 suggested a survival advantage associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative tumors 4 cm or larger,11 multiple studies28,29 have sought to refine size-specific chemotherapy indications. In an earlier population-based study from the NCDB, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a survival benefit in all patients with tumors larger than 3 cm, including 3.1- to 3.9-cm tumors.28 However, the authors did not examine other characteristics, such as high-risk pathologic features, that might also be associated with outcomes. A separate cohort study in a Japanese population examined the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-negative tumors 3 cm or smaller with vs without of high-risk features (VPI, LVI, or invasive components >2 cm).29 A survival advantage was seen in patients with high-risk features but only if chemotherapy was not platinum based; this finding counters the standard management of NSCLC in non-Japanese patients for whom platinum-based chemotherapy has the most robust data from randomized clinical trials. In contrast to the findings from these 2 observational studies, in the current study, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved survival only in tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm managed by sublobar resection. The differences in results from prior studies and our study could reflect differences in periods, study population, or type of chemotherapeutic agents used. The Japanese study predominately used oral fluoropyrimidines, such as tegafur-uracil, which makes a cross-study comparison difficult because platinum doublets are the most commonly used chemotherapy regimen in the US.30,31 Our results are, however, consistent with other retrospective studies involving patients with tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm that failed to show any significant association between disease-free survival and OS and adjuvant chemotherapy (although, to our knowledge, other studies have not examined the population that underwent sublobar resection).32,33,34

For tumors larger than 4 cm, our findings both support and contradict prior studies. Similar to other studies, we found a survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy for node-negative tumors larger than 4 cm to 5 cm.28,35 However, our data support a refined indication for chemotherapy, limiting it only to patients with at least 1 high-risk feature (which included 55% of tumors in this size category in our study). We believe that this refinement is not trivial because many patients may be able to avoid the potential toxic effects, adverse effects, and inconvenience of adjuvant chemotherapy if it is not associated with a survival benefit. Our study was exploratory and might not change practice at this point. However, if our results are validated, we estimate that approximately 400 US patients each year could potentially avoid chemotherapy based on the NCDB case mix. In patients with larger node-negative tumors (>5 cm), our study suggests a survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy irrespective of the presence of other high-risk features, which is similar to the results of prior studies.28

Sublobar resection (wedge resection and segmentectomy) as an indication for adjuvant chemotherapy may have interesting implications. More specifically, identifying a survival benefit associated with sublobar resection that is not associated with lobectomy could be the consequence of incomplete tumor removal or nodal evaluation.36 In other words, the chemotherapy could be mitigating a cancer risk that lobectomy alleviates (ie, chemotherapy is not needed), but sublobar resection does not.37 This finding would support earlier studies that suggest that lobectomy is the preferred approach for early-stage lung cancer.38 However, more recent studies have challenged the superiority of lobectomy.39,40,41 A recently accrued clinical trial (CALGB 140503) designed to answer this question may inform this debate in the near future.42 There are also a number of biological factors that may distinguish segmentectomy and wedge-amenable tumors (more peripheral, perhaps more likely well differentiated) from lobectomy-requiring tumors.43 If and where this finding fits into the ongoing debate over the role of sublobar and lobar NSCLC resection is unclear and beyond the scope of the study.

We also observed low rates of chemotherapy use in our study; even among patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, only 40% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy despite prior studies showing a survival benefit associated with chemotherapy in this group. On the other hand, up to 3% patients with tumors 3 cm or smaller received adjuvant chemotherapy despite lack of survival data for these patients. Our results should, however, be considered exploratory, and further studies of adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage NSCLC are warranted.

During the past decade, the indications for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with surgically managed NSCLC have been confirmed, challenged, and extended through an increasing number of observational studies.34,44,45 Clinicians are left trying to place findings of another such study into the care of specific patients, particularly as further predictive stratifications are likely to be found (eg, genetic factors). In this regard, our findings should not be the practice standard but should inform the practice standard.

Limitations

This study has some limitations in addition to those traditionally associated with observational studies. Although our study population was limited to patients who received multiagent chemotherapy, we were unable to account for differences in specific regimens and doses used because these data are not captured in the NCDB. Therefore, it is possible that patients who were given chemotherapy failed to receive an effective regimen, which could have obscured the benefit of chemotherapy. Similarly, the NCDB does not capture data on specific comorbidities, performance status, smoking, or pulmonary function that could have influenced not only the decision to assign patients to sublobar surgery but also the decision to offer adjuvant chemotherapy. Although segmentectomy is believed to offer outcomes similar to lobectomy, we were unable to perform further analyses to compare the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy after segmentectomy vs wedge resection owing to limitations in sample size.46,47 Similarly, evaluation of the association of neuroendocrine histologic characteristics with survival was not possible owing to limited sample size. In scenarios in which chemotherapy use was rare (eg, patients with ≤3-cm tumors), it is possible that the impact of chemotherapy was obscured by the negative prognostic implications of the clinical feature that motivated the use of chemotherapy but were not captured by the database (such as the fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on positron emission tomographic scan). Our study was sufficiently powered (>0.95) to detect the difference in survival for patients associated with the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in all groups except for the group with tumors larger than 3 cm to 4 cm (in which the power was 0.71). In addition, we were unable to evaluate cancer-specific survival and recurrence rates, which might have added more insight given the possibility of competing mortality risk in the adjuvant setting.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that tumor size alone is not associated with the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage, node-negative NSCLC. We believe that consideration should be given to tumor size, high-risk features, and potentially the extent of resection when discussing the role of adjuvant chemotherapy with this subset of patients.

eTable 1. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors ≤3 cm

eTable 2. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >3-4 cm

eTable 3. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >4-5 cm

eTable 4. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >5-7 cm

eTable 5. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Different Tumor Size Categories (≤3 cm, >3-4 cm, >4-5 cm and >5-7 cm)

eTable 6. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ≤3 cm Tumors After Adjustments for Clinically Significant Interactions

eTable 7. Association of Sublobar Surgery With Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ≤4 cm Cohort According to 1-cm Tumor Size Increments

eTable 8. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival (Measured From the Date of Diagnosis) After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Different Tumor Size Categories (≤3 cm, >3-4 cm, >4-5 cm and >5-7 cm)

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedor D, Johnson WR, Singhal S. Local recurrence following lung cancer surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Surg Oncol. 2013;22(3):156-161. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 8th ed Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon J-P, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. ; LACE Collaborative Group . Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3552-3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arriagada R, Auperin A, Burdett S, et al. ; NSCLC Meta-analyses Collaborative Group . Adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: two meta-analyses of individual patient data. Lancet. 2010;375(9722):1267-1277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60059-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douillard J-Y, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(9):719-727. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70804-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J; International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group . Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(4):351-360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. ; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group; National Cancer Institute of the United States Intergroup JBR.10 Trial Investigators . Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(25):2589-2597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waller D, Peake MD, Stephens RJ, et al. Chemotherapy for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the surgical setting of the Big Lung Trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(1):173-182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scagliotti GV, Fossati R, Torri V, et al. ; Adjuvant Lung Project Italy/European Organisation for Research Treatment of Cancer-Lung Cancer Cooperative Group Investigators . Randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage I, II, or IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(19):1453-1461. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss GM, Herndon JE II, Maddaus MA, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel plus carboplatin compared with observation in stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer: CALGB 9633 with the Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, and North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(31):5043-5051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kris MG, Gaspar LE, Chaft JE, et al. Adjuvant systemic therapy and adjuvant radiation therapy for stage I to IIIA completely resected non-small-cell lung cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology/Cancer Care Ontario clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(25):2960-2974. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.4401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv1-iv21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Non-small cell lung cancer. Version 3.2020. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- 15.Mallin K, Browner A, Palis B, et al. Incident cases captured in the National Cancer Database compared with those in U.S. population based central cancer registries in 2012-2014. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(6):1604-1612. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07213-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K, et al. Using the National Cancer Database for outcomes research: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(12):1722-1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Surgeons Welcome to the 2016 PUF Data Dictionary. Accessed January 1, 2020. http://ncdbpuf.facs.org

- 18.Amin MB, Gress DM, Vega LRM, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinze G, Wallisch C, Dunkler D. Variable selection—a review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom J. 2018;60(3):431-449. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201700067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, Bach PB, Begg CB. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(8):658-665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellera CA, MacGrogan G, Debled M, de Lara CT, Brouste V, Mathoulin-Pélissier S. Variables with time-varying effects and the Cox model: some statistical concepts illustrated with a prognostic factor study in breast cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661-3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SY, Lee JG, Kim J, et al. Efficacy of platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy in T2aN0 stage IB non-small cell lung cancer. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:151. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang L, Liang W, Shen J, et al. The impact of visceral pleural invasion in node-negative non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;148(4):903-911. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgensztern D, Du L, Waqar SN, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with T2N0M0 NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1729-1735. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsutani Y, Imai K, Ito H, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer with high-risk factors for recurrence: a multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15, suppl):8500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.8500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langer CJ, Moughan J, Movsas B, et al. Patterns of care survey (PCS) in lung cancer: how well does current U.S. practice with chemotherapy in the non-metastatic setting follow the literature? Lung Cancer. 2005;48(1):93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stinchcombe TE, Detterbeck FC, Lin L, Rivera MP, Socinski MA. Beliefs among physicians in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(9):819-826. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f478a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HJ, Park HS, Cha YJ, et al. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage IB non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(4):2279-2287. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.03.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Zhang C, Sun Z, et al. Propensity-matched analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:75-82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Wu N, Lv C, Yan S, Yang Y Should patients with stage IB non-small cell lung cancer receive adjuvant chemotherapy? a comparison of survival between the 8th and 7th editions of the AJCC TNM staging system for stage IB patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145(2):463-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roselli M, Mariotti S, Ferroni P, et al. Postsurgical chemotherapy in stage IB nonsmall cell lung cancer: long-term survival in a randomized study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(4):955-960. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khullar OV, Liu Y, Gillespie T, et al. Survival after sublobar resection versus lobectomy for clinical stage IA lung cancer: an analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(11):1625-1633. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veluswamy RR, Mhango G, Bonomi M, et al. Adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with early-stage lung cancer treated with limited resection. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(6):622-628. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-127OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV; Lung Cancer Study Group . Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60(3):615-622. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yendamuri S, Sharma R, Demmy M, et al. Temporal trends in outcomes following sublobar and lobar resections for small (≤2 cm) non-small cell lung cancers—a Surveillance Epidemiology End Results database analysis. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):27-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao C, Gupta S, Chandrakumar D, Tian DH, Black D, Yan TD. Meta-analysis of intentional sublobar resections versus lobectomy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3(2):134-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada M, Koike T, Higashiyama M, Yamato Y, Kodama K, Tsubota N. Radical sublobar resection for small-sized non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(4):769-775. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altorki NK, Wang X, Wigle D, et al. Perioperative mortality and morbidity after sublobar versus lobar resection for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: post-hoc analysis of an international, randomised, phase 3 trial (CALGB/Alliance 140503). Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(12):915-924. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30411-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Speicher PJ, Gu L, Gulack BC, et al. Sublobar resection for clinical stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer in the United States. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17(1):47-55. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora RK, Gibson AW, Bebb DG, Cheung WY. The population-based impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on outcomes in T2N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43(7):496-503. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmad U, Crabtree TD, Patel AP, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with improved survival in locally invasive node negative non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(1):303-307. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.01.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dziedzic R, Zurek W, Marjanski T, et al. Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of lobectomy versus sublobar resection from the Polish National Lung Cancer Registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(2):363-369. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedetti B, Bertolaccini L, Rocco R, Schmidt J, Solli P, Scarci M. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(6):1615-1623. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors ≤3 cm

eTable 2. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >3-4 cm

eTable 3. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >4-5 cm

eTable 4. Propensity Score–Adjusted Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Overall Survival in Tumors >5-7 cm

eTable 5. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Different Tumor Size Categories (≤3 cm, >3-4 cm, >4-5 cm and >5-7 cm)

eTable 6. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ≤3 cm Tumors After Adjustments for Clinically Significant Interactions

eTable 7. Association of Sublobar Surgery With Survival After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in ≤4 cm Cohort According to 1-cm Tumor Size Increments

eTable 8. Association of High-Risk Features and Survival (Measured From the Date of Diagnosis) After Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Different Tumor Size Categories (≤3 cm, >3-4 cm, >4-5 cm and >5-7 cm)