Highlights

-

•

The dermis of Ichthyophis beddomei bounds with mucous and granular glands.

-

•

Dermal scales, with squamulae, are embedded in the scale pockets.

-

•

GC–MS analysis of skin secretion revealed 27 compounds.

Keywords: Ichthyophis beddomei, TEM, SEM, Dermal scales, Skin glands

Abstract

The caecilian amphibians are richly endowed with cutaneous glands, which produce secretory materials that facilitate survival in the hostile subterranean environment. Although India has a fairly abundant distribution of caecilians, there are only very few studies on their skin and secretion. In this background, the skin of Ichthyophis beddomei from the Western Ghats of Kerala, India, was subjected to light and electron microscopic analyses. There are two types of dermal glands, mucous and granular. The mucous gland has a lumen, which is packed with a mucous. The mucous-producing cells are located around the lumen. In the granular gland, a lumen is absent; the bloated secretory cells, filling the gland, are densely packed with granules of different sizes which are elegantly revealed in TEM. There is a lining of myo-epithelial cells in the peripheral regions of the glands. Small flat disk-like dermal scales, dense with squamulae, are embedded in pockets in the dermis, distributed among the cutaneous glands. 1–4 scales of various sizes are present in each scale pocket. Scanning electron microscopic observation of the skin surface revealed numerous glandular openings. The skin gland secretions, exuded through the pores, contain fatty acids, alcohols, steroid, hydrocarbons, terpene, aldehyde and a few unknown compounds.

1. Introduction

In view of the limited distribution confining to the rain-fed tropical regions, the concealed fossorial life, and mistaken identity with snakes, caecilians are the least studied vertebrates (Gomes et al., 2012). Only 212 caecilian species are known, and are assigned to 10 families (www.amphibiaweb.org, 8th March 2019). Being a tropical country, India is home to diverse forms of caecilians (Taylor, 1968). Out of the 39 species of caecilians reported from India, 26 are from Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot (Daniels, 1992, Kotharambath et al., 2013, Kotharambath et al., 2017).

Icthyophis beddomei is a comparatively small-bodied oviparous caecilian belonging to the family Ichthyophiidae. It is commonly called yellow-striped caecilian. The brownish body has two prominent lateral yellow stripes which become broad towards the head. Caecilians are a much-neglected group of animals in terms of research, little has been done with regard to this species. Its structural variation of oviduct in relation to the annual cycle (Masood-Parveez and Nadkarni, 1991), inter-renal gland structure and function (Masood-Parveez et al., 1992), ovarian cycle (Masood-Parveez and Nadkarni, 1993a), ovary (Masood-Parveez and Nadkarni, 1993b) and pituitary gland (Masood-Parveez et al., 1994) have been studied. Thus, I. beddomei became the animal of choice in this study.

Amphibian skin is an exocrine organ that produces skin secretion, which contributes to several aspects of biology, especially homeostasis, cutaneous respiration, conspecific communication, offence and defence (Fox, 1986, Duellman and Trueb, 1986). These roles are generally assigned to the wide variety of bio-active molecules that are present in the skin gland secretions (Zasloff, 1987, Zasloff, 2002, Erspamer, 1994, Fredericks and Dankert, 2000, Gomes et al., 2007, Pereira et al., 2018, Siano et al., 2018). Several bioactive peptides, amines (Erspamer, 1994) and over 800 alkaloids have been reported from anurans and salamanders (Daly et al., 2005). Since the caecilian amphibians are fossorial, the skin secretions from the cutaneous glands viz., mucous glands and poison/granular glands, play all these critical roles very efficiently (Jared et al., 2018). The cutaneous glands of Ichthyophis orthoplicatus and Ichthyophis kohtaoensis have been elaborately studied (Fox, 1983). Arun et al. (2018) reported the ultrastructural organization of the cutaneous glands of Ichthyophis tricolor and Uraeotyphlus cf. oxyurus. Unlike the skin of urodeles and anurans, the caecilian skin does not show any glandular accumulations (macro-glands) such as parotoids typically found in salamanders and toads (Brodie and Gibson, 1969, Jared et al., 1999, Jared et al., 2018, Regis-Alves et al., 2017). The secretions of the granular glands in Ichthyophis glutinosus were found to be non-venomous (Gabe, 1971), whereas a report that followed suggested that the granular gland secretion has a defensive role, as it contains repellent or toxic compounds that would distract the predators (Breckenridge and Murugapillai, 1974). There is no literature on the metabolomic study of the skin secretion of caecilians. In view of the several potential roles of the bio-active molecules, and the scope for research applications, it was conceived that it would be pertinent to investigate I. beddomei from this perspective.

Unlike the anurans and urodeles, most of the caecilian amphibians possess dermal scales which have been investigated in fair detail in the genera Dermophis, Ichthyophis, Hypogeophis, Uraeotyphlus, Geotrypetes, Herpele, etc. (Wake, 1975, Casey and Lawson, 1979, Zylberberg et al., 1980, Perret, 1982, Wake and Nygren, 1987, Zylberberg and Wake, 1990, Arun et al., 2018, Arun et al., 2019). The caecilian dermal scales are composed of a basal plate with layers of unmineralized collagen fibres. They are topped with mineralized squamulae (Zylberberg and Wake, 1990, Arun et al., 2019). The dermal scales of I. beddomei have not yet been looked into.

Therefore, the present study investigates the dermal glands, scales and secretome of I. beddomei using microscopic and metabolomics approaches.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

Specimens of I. beddomei (Fig. 1) were collected from Wayanad district, Kerala (1.7923° N, 76.1663° E) under permission from the Kerala State Forest Department (Order No-WL10-23554/2015). During transport to the lab, animals were kept in plastic bottles, with air holes, containing the humid soil collected from the area of collection, with earthworms as feed. Three animals (415 ± 17 mm long, independent of sex) were maintained in a terrarium in the lab. The mid-dorsal, ventral and lateral skins were dissected under 25% MS-222 (Tricaine methane sulfonate) anaesthesia. The procedures and practices of animal care and handling were in strict adherence to the policies of the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee.

Fig. 1.

I. beddomei.

2.2. Light and transmission electron microscopic (LM and TEM) observations of skin

The animal handling techniques were adopted from Beyo et al., 2008, Arun et al., 2018. The dissected skin samples (n = 3) were washed in amphibian Ringer solution [6.6 g NaCl, 0.15 g KCl, 0.15 g CaCl2, and 0.2 g NaHCO3 added to 1L distilled water], followed by fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution, post-fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide, and embedding in methacrylate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). One-micron thick sections (semithin) were stained with toluidine blue O (TBO) and observed in an Axio-3 research microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Leica ultra-microtome (Jena, Germany) was used to cut ultrathin sections, which were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and subjected to observation in a Tecnai 12G2 Biotwin transmission electron microscope.

2.3. Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) analysis of skin surface morphology

The skin samples, as mentioned vide supra, and dermal scales on dorsal side from three specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and dehydrated for SEM (Robinson and Gray, 1990). The samples were dried adopting critical-point method, and mounted to visualize the skin surface morphology. After coating with gold palladium, the samples were observed in a Field Emission scanning electron microscope (SEM; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.4. GC MS analysis

Dichloromethane was used as solvent to extract out the skin gland secretion (Nowack et al., 2017). The dissected skin samples (n = 3) were separately kept in dichloromethane for 48 h. Thereafter, the skin was trashed and the dichloromethane was filtered to remove the debris (Poth et al., 2012, Poth et al., 2013) and injected to GC MS. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis was done on Agilent Technologies 7890A GC (Germany) with Column db5 MS (30 m 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 µm), flow rate 1.5 mL/min and helium as carrier gas. Splitless injection was done at 250 ⁰C. The MS transfer line was maintained at 300⁰ C, the ion source at 250 ⁰C and was operated with 70 eV ionization energy. The mass spectrum was recorded in full scan mode. Identification of the compounds was achieved by comparison with MS-spectra provided by the software AMDIS/NIST/ NIH Mass Spectral Database.

3. Results

3.1. Light microscopic observations of cutaneous glands and dermal scales

There are two types of skin glands, mucous and granular, present in the dermis of I. beddomei (Fig. 2A, B). The mucous gland appears oval in shape and the prominent mucous-producing cells are arranged around a distinct lumen, which is filled with mucous. The granular glands, which lack a lumen, are considerably larger than the mucous glands and are round or elliptical in shape (Fig. 2B). The secretory epithelial cells are compactly arranged, much in the form of cords, around the periphery, and the cytoplasm of cell body extends into the core of the gland. Granules of different sizes and densities are densely present in the granular glands (Fig. 2B). The dermal scales are arranged in the scale pockets along with the cutaneous glands (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Light micrographs of cutaneous glands and dermal scales in the skin of I. beddomei. A, B: Sections of mucous, granular glands and dermal scales of I. beddomei. Ep, Epidermis; D, Dermis; Gr, Granules; MyC, Myoepithelial cells; GPC, Granule producing cells; MPC, Mucous producing cells; Mu, Mucous vesicle; S, Scale.

3.2. TEM observations of cutaneous glands

There are myo-epithelial cells stretching along the lining of both granular and mucous glands (Fig. 3A, C). The granule-producing cells are located along the periphery of the gland (Fig. 3A). Granules of various sizes are present in the cytoplasm towards the core of the gland (Fig. 3A, B). The mucous gland is densely packed with mucous vesicles (Fig. 3C). The mucous-producing cells are darkly stained and located in the periphery of the gland (Fig. 3C). A few mucous vesicles are collapsed and the mucoid material is dispersed in the lumen, probably in preparation for discharge outside (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

TEM images of cutaneous glands in the skin of I. beddomei. A: Granular gland. B: Enlarged view of granules in the granular gland. C: Discharge of mucous droplet into the lumen of the mucous gland. Gr, Granules; MyC, Myoepithelial cells; GPC, Granule Producing Cells; MPC, Mucous producing cells; Mu, Mucous vesicle.

3.3. SEM observations of skin surface

The epithelial cells of the skin surface have micro-ridges with round, oval and polymorphic glandular openings (Fig. 4A, B). The latter are funnel type, where the epithelial cells lining the rim descend into the funnel (Fig. 4A, B, 5C, D). The glandular contents are released through these openings to be spread along the body surface (Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 4.

SEM images of the skin surface of I. beddomei. A, B: Dorsal and ventral skin, respectivey, showing glandular openings (GO).

Fig. 5.

SEM images of the glandular openings of I. beddomei. Dorsal (A, B) and ventral (C, D) skin showing glandular openings (GO).

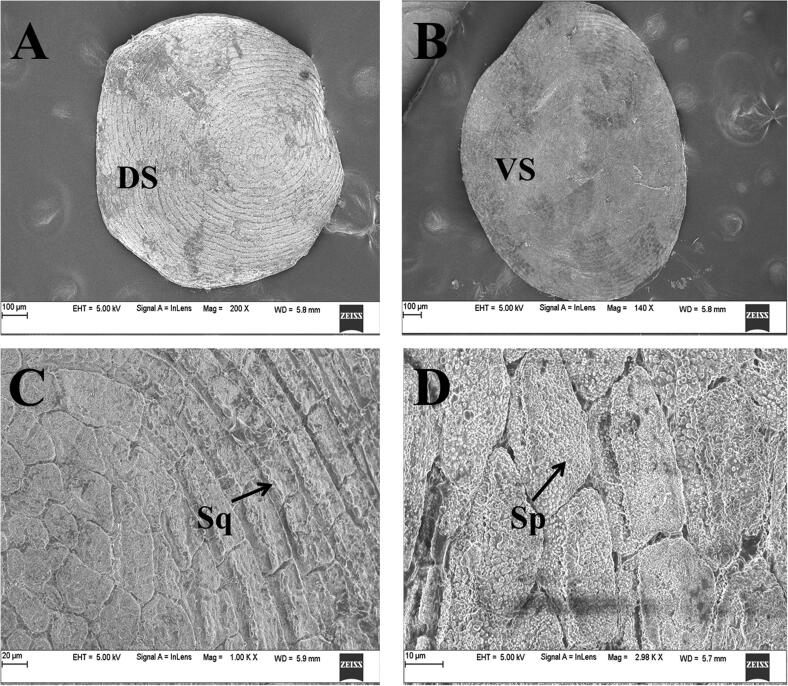

3.4. SEM observations of dermal scales

The scales are embedded in scale pockets amidst the cutaneous glands in the dermis. The scales are oval in shape and measure a diameter of 700 – 1000 µm. Squamulae are present along the dorsal surface of the scale and are organized in a ring-like arrangement (Fig. 6A). The ventral surface of the scale lacks squamulae (Fig. 6B). The squamulae are irregular in shape at the centre, and rectangular along the periphery (Fig. 6C). There are spherules located on the squamulae (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

SEM images of dermal scales of I. beddomei. A: Dorsal surface of the dermal scale. B: Ventral surface of the dermal scale. C: Enlarged view of a dermal scale showing squamulae. D: Enlarged view of a dermal scale showing spicules. DS, Dorsal surface; VS, Ventral surface; Sq, Squamule; Sp, Spicules.

3.5. GC–MS analysis

The GC–MS analysis of skin extracts of I. beddomei yielded 27 compounds (Fig. 7, Table 1), which included three fatty acids, six alcohols, one terpene, five hydrocarbons, one steroid, one aldehyde and ten unidentified compounds (Table 1).

Fig. 7.

7A. GC MS chromatogram of I. beddomei skin secretion. 7B. Overview of the compounds identified from the skin secretions of I. beddomei using GC MS.

Table 1.

Compounds identified from the skin secretions of I. beddomei using GC MS.

| No | Name | Class | RT* | Formula | MW (Da)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown 1 | – | 7.60 | – | – |

| 2 | Unknown 2 | – | 8.09 | – | – |

| 3 | Unknown 3 | – | 8.18 | – | – |

| 4 | Unknown 4 | – | 8.82 | – | – |

| 5 | Unknown 5 | – | 8.90 | – | – |

| 6 | 1-Tridecene | Hydrocarbon | 16.58 | C13H26 | 182.35 |

| 7 | Pentanedioic acid | Fatty acid | 17.45 | C5H8O4 | 132.15 |

| 8 | 8-Heptadecene- 9-octyl | Hydrocarbon | 18.49 | C25H50 | 350.69 |

| 9 | Unknown 6 | – | 19.50 | – | – |

| 10 | Unknown 7 | – | 20.65 | – | – |

| 11 | Hexadecane | Hydrocarbon | 20.78 | C16H34 | 226.26 |

| 12 | 1-Bromo tridecane | Hydrocarbon | 21.97 | C13H27Br | 263. 29 |

| 13 | Unknown 8 | – | 22.50 | – | – |

| 14 | 2-Isopropyl-5-methyl-1-heptanol | Alcohol | 22.61 | C11H24O | 172.18 |

| 15 | E-15-Heptadecenal | Aldehyde | 24.31 | C17H32O | 252. 45 |

| 16 | Octadecane | Hydrocarbon | 24.42 | C18H38 | 254.49 |

| 17 | Unknown 9 | – | 26.16 | – | – |

| 18 | 1-Eicosanol | Alcohol | 27.98 | C20H42O | 298.52 |

| 19 | Hexadecanoic acid | Fatty acid | 28.41 | C16H32O2 | 256.47 |

| 20 | 1-Dodecanol, 2-octyl | Alcohol | 30.25 | C20H42O | 298.52 |

| 21 | Behenic alcohol | Alcohol | 30.68 | C22H46O | 326.35 |

| 22 | Octadecanoic acid | Fatty acid | 31.34 | C18H36O2 | 284.31 |

| 23 | n-Tetracosanol | Alcohol | 33.48 | C24H50O | 354.68 |

| 24 | Unknown 10 | – | 34.81 | – | – |

| 25 | Octacosanol | Alcohol | 37.42 | C28H58O | 410.44 |

| 26 | Squalene | Terpene | 37.54 | C30H50 | 410.71 |

| 27 | Cholesterol | Steroid | 38.68 | C27H46O | 386.65 |

Retention Time.

Molecular Weight.

4. Discussion

The amphibian skin in general, and the topic of research in this article in particular, contains mainly two types of cutaneous glands. The mucous glands, possessing a central lumen, secrete a mucoid substance which until discharge accumulates in the cytoplasm in mucous vesicles and then released into the lumen. The vesicles at some stage mucify so as to be discharged outside as the mucous (Jared et al., 2018, Arun et al., 2018, Arun et al., 2019). Jared et al. (2018) reported two types of mucous glands in Siphonops annulatus each possessing two types of cells taking up stains differently. The mucous glands produce mucoproteoglycans and mucopolysaccharides (Heiss et al., 2009). The granular glands, sometimes known as poison glands (Jared et al., 2018), secrete a granular material (Duellman and Trueb, 1994, Toledo and Jared, 1995). The granular gland secretory material is rich in bioactive substances such as peptides, amines and alkaloids (Erspamer, 1994).

From the functional point of view, the mucous secreted by the mucous gland helps to keep the skin moist and controls the pH of the body surface (Fox, 1994, Toledo and Jared, 1995). Since mucous is a viscous material, it makes the animal slimy and slippery so as to render it difficult for predators to seize (Toledo and Jared, 1995, Stebbins and Cohen, 1997). The mucous in the skin of frog Rana catesbeiana is known to help in keeping the body cool via evaporation of moisture during high temperatures (Lillywhite, 1971). According to Gabe (1971) the mucus of Ichthyophis glutinosus contains a hydrophilic mucin, which helps in maintaining the skin moist and, thereby, facilitate cutaneous respiration. Breckenridge and Murugapillai (1974) found the caecilian mucous gland secretion to be acidic, with sulphate and carboxyl groups, and contain vicinal glycols. According to Jared et al. (2018), as the granular gland matures, the number of vesicles in the granular glands increases and the cytoplasm becomes poorer in organelles, and it is ready to discharge the content. The cell membrane disappears from the core of the gland during the final stage of maturation. It results in a syncytial gland (Navas et al., 1982, Reyer et al., 1992). Williams and Larsen (1986) reported that the granular glands of Ambystoma macrodactylum may play role in poison production as well as nutrient storage. The secretory material of the granular glands is rich in biologically active molecules which would play eco-physiological roles such as antimicrobial and antipredatory (Duellman and Trueb, 1986). There are only a few reports on bioactive properties of caecilian skin secretion till now. Bioactive properties of the skin secretion of a caecilian amphibian Siphonops annulatus have been reported (Pinto et al., 2014). Schwartz et al. (1997) studied the haemolytic and cardiotoxic properties of the skin secretions of another caecilian – Siphonops paulensis. We also found the antimicrobial properties of skin secretions of I. tricolor and U. cf. oxyurus (unpublished data). The numerous funnel-shaped glandular openings with polymorphic profile on the surface have been reported in the tree frog Hyla arborea (Witalmska and Kubiczek, 1998), and caecilians I. tricolor, U.cf. oxyurus and G. ramaswamii (Arun et al., 2018, Arun et al., 2019).

The dermis of caecilian amphibians is unique in possessing scales in dermal pockets (Fox, 1983). The morphology of caecilian dermal scales has been described in Dermophis mexicanus (Ochoterena, 1932), Ichthyophis orthoplicatus and Ichthyophis kohtaoensis (Fox, 1983), I. tricolor and U. cf. oxyurus (Arun et al., 2018), Dermophis species (Cockerell, 1912), Ichthyophis glutinosus (Gabe, 1971) and Dermophis mexicanus and Microcaecilia unicolor (Zylberberg and Wake, 1990). Species belonging to Scoleomorphidae and Typhlonectidae do not possess dermal scales, though Typhlonectes compressicauda apparently possesses minute scales in the hinder region of the body (Wake, 1975). A common feature of squamulae in all species examined so far is the mineralized material deposited as globules in the dermal scales. We also found mineralization in I. beddomei. Mineralization does not occur in the basal plate (Casey and Lawson, 1979). The shapes and distribution of squamulae in the dorsal surface of the scales in I. beddomei are similar to the other Ichthyophis sp. reported. The peripheral squamulae in Ichthyophis are rectangular (Zylberberg et al., 1980, Arun et al., 2018) while in Geotrypetes (Perret, 1982) and Dermophis (Wake and Nygren, 1987) they are circular. The squamulae are almond shaped in G. Ramaswamii (Arun et al., 2019). The squamule present in the dermal scales of I. tricolor and U. cf. oxyurus are rectangular in the peripheral region and irregular centrally and scales are present from the anterior to posterior region of the body (Arun et al., 2018), the same as in I. beddomei found in this study.

In the present study we adopted metabolomics profiling of I. beddomei skin secretion using GC MS. Communication within and between species is fundamental to life at all levels (Wyatt, 2003). How caecilians communicate with each other is a mystery. The caecilians are fossorial in nature. They may communicate through sensory tentacles and/or volatiles. We found five hydrocarbons in the skin secretion of I. beddomei. Hydrocarbons like decane,2,3,5,8-tetramethyl, 1-nonene,4,6,8-trimethyl and tetradecane,2,6,10-trimethyl have been reported in the skin secretions of the Brazilian frog Bokermannohyla alvarengai (Centeno et al., 2015). So far, role of hydrocarbons in chemical communication is not yet reported in any amphibian species. However, in insects air-borne communication occurs mainly through cuticular hydrocarbons (Wyatt, 2003, Leonhardt et al., 2016).

Squalene is an intermediate metabolite in the synthesis of cholesterol (Gregory and Kelly, 1999). It is an effective oxygen scavenging agent (Bargossi et al., 1994). Therefore, it may be suggested that squalene present in the skin secretion of I. beddomei may act as an antioxidant and protect the skin from oxidative damages. Achiraman et al. (2011) reported that squalene produced from the clitoral gland of the rat acts as a semi-volatile and may serve as a chemo-signal. According to Centeno et al. (2015) the major lipid components present in the skin secretion of Bokermannohyla alvarengai are hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and octadecanoic acid methyl ester. Hexadecanoic acid, pentanedioic acid, octadecanoic acid and cholesterol were also identified in the skin secretions of I. beddomei. Kupfer et al. (2006) also found skin secretions of the caecilian amphibian Boulengerula taitanus as rich in lipids. The lipids present in Rana tigerina skin play an important role during the proliferative phase of wound healing (Sai and Babu, 1998).

Alkanols and lactones as pheromonal compounds were reported in the femoral gland secretion of mantellid frogs by Poth et al., 2012, Poth et al., 2013. Alcohols, sesquiterpenes and macrolides may have an important role in sexual communication of hyperoliids (Starnberger et al., 2013). We report six alcohols from the skin secretion of I. beddomei. Aromatic alcohol, methyl branched alcohols and straight-chain primary alcohols were reported from the skin secretion of two species of hypsiboas tree frogs (Brunetti et al., 2015).

There are two mechanisms which can explain the presence of secretory compounds in the skin of an amphibian, (i) dermal uptake, and (ii) dietary uptake (Smith et al., 2004). Some caecilians (Afrocaecilia taitana) were found to have vegetable matter in their diet (Hebrard et al., 1992). Similar observations were made in Chthonerpeton indistinctum by Gudynas and Williams (1986) and Typhlonectes compressicaudus by Exbrayat et al. (1985). We also found the presence of plant materials along with ants, mites, soil and remnants of earthworms in the gut. Thus, we suggest that the dermal uptake, dietary uptake or both mechanisms may exist in I. beddomei.

Our study revealed the presence of alcohols, hydrocarbons, cholesterol, aldehyde, fatty acids and terpene in the skin secretion of I. beddomei. Further, there were few compounds that were not identified. The fact is that, the unidentified portion may contain potential volatile molecules. We conclude that caecilian skin glands in general, and those of I. beddomei in particular, secrete substances which would play multiple roles including cutaneous respiration, offence and defence, free radical scavenging and conspecific communication. Since very little is known about the volatile compounds present in the skin secretions of caecilian amphibians, investigation of skin secretion of these amphibians adopting secretomic approach offers enormous scope.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Central University of Kerala for the infrastructural facility. We heartily acknowledge the TEM facility of Wellcome Trust Laboratory of Christian Medical College & Hospital, Vellore, India. We thank Dr. T. B. Sridharan and Mr. Alwin Patrik, Department of Bioscience, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India, for assistance in the SEM analysis. Finally, we thank IISc Bangalore for providing the GC MS facility.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Achiraman S., Archunan G., Abirami B., Kokilavani P., Suriyakalaa U., Sankar G.D., Kamalakkannan S., Kannan S., Habara Y., Sankar R. Increased squalene concentrations in the clitoral gland during the estrous cycle in rats: an estrus-indicating scent mark? Theriogenology. 2011;76:1676–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arun D., Reston S.B., Kotharambath R., Akbarsha M.A., Oommen O.V., Lekha D. Light and electron microscopic observations on the organization of skin and associated glands of two caecilian amphibians from Western Ghats of India. Micron. 2018;106:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arun D., Akbarsha M.A., Oommen O.V., Divya L. Light and transmission electron microscopic structure of skin glands and dermal scales of a caecilian amphibian Gegeneophis ramaswamii, with a note on antimicrobial property of skin gland secretion. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2019:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargossi A.M., Battino M., Gaddi A. Exogenous CoQ10 preserves plasma ubiquinone levels in patients treated with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 1994;24:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02592449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyo R.S., Divya L., Oommen O.V., Akbarsha M.A. Accumulation of yolk in a caecilian (Gegeneophis ramaswamii) oocyte: A light and transmission electron microscopic study. J. Morphol. 2008;269:1412–1424. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie E.D., Jr., Gibson L.S. Defensive behaviour and skin glands of the northwestern salamander, Ambystomagracile. Herpetologica. 1969;25:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge W.R., Murugapillai R.M. Mucous glands in the skin of Ichthyophis glutinosus (Amphibia: Gymnophiona) Ceylon J. Sci. 1974;11:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti A.E., Merib J., Carasek E. Frog volatile compounds: application of in vivo SPME for the characterization of the odorous secretions from two species of tree frogs. J. Chem. Ecol. 2015;41:360–372. doi: 10.1007/s10886-015-0564-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J., Lawson R. Amphibians with scales: The structure of the scale in the caecilian Hypogeophis rostratus. British J. Herpetol. 1979;5:831–833. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno F.C., Antoniazzi M.M., Andrade D.V., Kodama R.T., Sciani J.M., Pimenta D.C., Jared C. Anuran skin and basking behavior: The case of the tree frog Bokermannohyla alvarengai (Bokermann, 1956) J. Morphol. 2015;276:1172–1182. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerell T.D.A. The scales of Dermophis. Science. 1912;36:631. doi: 10.1126/science.36.933.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J.W., Spade T.F., Garraffo H.M. Alkaloids from amphibian skin: A tabulation of over eight hundred compounds. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1556–1575. doi: 10.1021/np0580560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R.J.R. Geographical distribution patterns of amphibians in the Western Ghats, India. J. Biogeogr. 1992;19:521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Duellman W.B., Trueb L. McGraw-Hill; New York. p: 1986. Biology of Amphibians; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Duellman W.E., Trueb L. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 1994. Biology of Amphibians. [Google Scholar]

- Erspamer V. Bioactive secretions of the amphibian integument. In: Heatwole H., Barthalmus G.T., editors. Amphibian Biology. The Integument. Surrey Beatty and Sons; Chipping Norton, NSW: 1994. pp. 179–350. [Google Scholar]

- Exbrayat J.M., Delsol M. Reproduction and growth of Typhlonectes compressicaudus, a viviparous gymnophione. Copeia. 1985;4:950–955. [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. The skin of Ichthyophis (Amphibia:Caecilia): An ultrastructural study. J. Zool. 1983;199:223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. Dermal glands. In: Bereiter-Hahn J., Matoltsky A.G., Richards K.S., editors. Vol. 2. Springer; Berlin: 1986. pp. 116–135. (Biology of the Integument. Vertebrates). [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. The structure of the integument. In: Heatwole H., Barthalmus G.T., editors. Amphibian Biology, The Integument. Surrey Beatty and Sons; Chipping Norton, NSW: 1994. pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks L.P., Dankert J.R. Antibacterial and haemolytic activity of the skin of the terrestrial salamander Plethodon cinereus. J. Exp. Zool. 2000;287:340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabe M. Doneeshistologiques sure le tegument d’Ichthyophis glutinosus L. (Batracien Gymnophione) Annales des sciences Naturelles, Zoologie Paris, 12eme series. 1971;13:573–608. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A., Giri B., Saha A., Mishra R., Dasgupta S.C., Debnath A., Gomes A. Bioactive molecules from amphibian skin: their biological activities with reference to therapeutic potentials for possible drug development. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2007;45:579–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A.D., Antoniazzi M.M., Navas C.A., Moreira R.G., Jared C. Review of the reproductive biology of caecilians. South Am. J. Herpetol. 2012;7:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory S., Kelly N.D. Squalene and its potential clinical uses. Alternative Med. Rev. 1999;4:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudynas E., Williams J.D. The southernmost population of a caecilian, Chthonerpeton indistinctum, in Uruguay. J. Herpetol. 1986;20:250–253. [Google Scholar]

- Heiss E., Natchev N., Rabanser A., Weisgram J., Hilgers H. Three types of cutaneous glands in the skin of the salamandrid Pleurodeles waltl. A histological and ultrastructural study. J. Morphol. 2009;70:892–902. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrard J.J., Maloiy G.M.O., Alliangana D.M.I. Notes on the habitat and diet of Afrocaecilia taitana (Amphibia: Gymnophiona) J. Herpetol. 1992;26:513–515. [Google Scholar]

- Jared C., Navas C.A., Toledo R.C. An appreciation of the physiology and morphology of the caecilians (Amphibia:Gymnophiona) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1999;123:313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Jared C., Mailho-Fontana P.L., Marques-Porto R., Sciani J.M., Pimenta D.C., Brodie E.D., Jr., Antoniazzi M.M. Skin gland concentrations adapted to different evolutionary pressures in the head and posterior regions of the caecilian Siphonops annulatus. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotharambath R., Reston S.B., Divya L., Akbarsha M.A., Oommen O.V. Caecilians - The limbless elusive amphibians: In the backdrop of Kerala region of the Western Ghats. In: Singaravelan N., editor. Rare Animals of India. Bentham Science Publishers; Oak Park, USA: 2013. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kotharambath R., Laladhas K.P., Oommen V.O. In: Caecilian (Amphibia: Gymniophiona) diversity of Kerala. Oommen V.O., Laladas K.P., editors. Kerala State Biodiversity Board; Thiruvananthapuram Kerala: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer A., Muller H., Antoniazzi M.M., Jared C., Greven H., Nussbaum R.A., Wilkinson M. Parental investment by skin feeding in a caecilian amphibian. Nature. 2006;440:13. doi: 10.1038/nature04403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt S.D., Florian Menzel F., Nehring V., Schmitt T. Ecology and evolution of communication in social insects. Cell. 2016;164:1277–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillywhite H.B. Thermal modulation of cutaneous mucous discharge as a determinant of evaporative water loss in the frog Rana catesbeiana. Comparative Biochem. Physiol. - Part A. 1971;73:84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Masood-Parveez U., Nadkarni V.B. Morphological, histological, histochemical and annual cycle of the oviduct in Ichthyophis beddomei (Amphibia: Gymnophiona) J. Herpetol. 1991;25:234–237. [Google Scholar]

- Masood-Parveez U., Nadkarni V.B. The ovarian cycle in an oviparous gymnophione amphibian, Ichthyophis beddomei (Peters) J. Herpetol. 1993;27:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Masood-Parveez U., Nadkarni V.B. Morphological, histological and histochemical studies on the ovary of an oviparous caecilian, Ichthyophis beddomei (Peters) J. Herpetol. 1993;27:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Masood-Parveez U., Bhatta G.K., Nadkarni V.B. Inter renal of a female gymnophione amphibian, Ichthyophis beddomei, during the annual reproductive cycle. J. Morphol. 1992;211:201–206. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052110208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood-Parveez U., Bhatta G.K., Nadkarni V.B. The pituitary gland of the oviparous caecilian, Ichthyophis beddomei. J. Herpetol. 1994;28:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Navas P., Bueno C., Hidalgo J., Aijon J., Lopez-Campos J.L. Secretion and secretory cycle of integumentary serous glands in Pleurodeles waltl. ii. Mich. Bas Appl. Histochem. 1982;26:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack C., Peram P.S., Wenzel S., Rakotoarison A., Glaw F., Poth D., Schulz S., Vences M. Volatile compound secretion coincides with modifications of the olfactory organ in mantellid frogs. J. Zool. 2017;303:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira K.E., Crother B.I., Sever D.M., Fontenot C.L., Jr., Pojman J.A., Sr., Wilburn D.B., Woodley S.K. Skin glands of an aquatic salamander vary in size and distribution and release antimicrobial secretions effective against chytrid fungal pathogens. J. Exp. Biol. 2018;221:jeb183707. doi: 10.1242/jeb.183707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret J. Les Bcailles dedeux Gymnophione africains (Batraciensapodes), observk au microscope 6lBctronique a bdayage. Bonnkl Beitr. 1982;33:343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto E.G., Antoniazzi M.M., Jared C., Tempone A.G. Antileishmanial and antitrypanosomal activity of the cutaneous secretion of Siphonops annulatus. J. Venomous Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2014;20:50. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-20-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poth D., Wollenberg K.C., Vences M., Schulz S. Volatile amphibian pheromones: macrolides from mantellid frogs from Madagascar. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2012;51:2187–2190. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poth D., Peram P.S., Vences M., Schulz S. Macrolides and alcohols as scent gland constituents of the Madagascan frog Mantidactylus femoralis and their intraspecific diversity. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1548–1558. doi: 10.1021/np400131q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regis-Alves E., Jared S.G.S., Mauricio B., Mailho-Fontana P.L., Antoniazzi M.M., Fleury-Curado M.C., Brodie E.D., Jr., Jared C. Structural cutaneous adaptations for defence in toad (Rhinella icterica) parotoid macroglands. Toxicon. 2017;137:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyer R.W., Liou W., Pinkstaff C.A. Morphology and glycoconjugate histochemistry of the palpebral glands of the adult newt, Notophthalmus viridescens. J. Morphol. 1992;211:165–178. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052110205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G., Gray T. Electron microscopy: specialized techniques. In: Bancroft J.D., Stevens A., editors. Theory and practice of histological techniques. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1990. pp. 566–567. [Google Scholar]

- Sai K.P., Babu M. Growth potential of Rana tigerina skin lipids in cell cultures in vitro. Cellular and Developmental Biology –. Animal. 1998;34:561–567. doi: 10.1007/s11626-998-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E.F., Schwartz C.A., Sebben A., Mende E.G. Cardiotoxic and hemolytic activities of the caecilian Siphonops paulensissk in secretion. J. Venomous Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 1997;3:190. [Google Scholar]

- Siano A., Humpola M.V., de Oliveira E., Albericio F., Simonetta A.C., Lajmanovich R., Tonarelli G.G. Leptodactylus latrans amphibian skin secretions as a novel source for the isolation of antibacterial peptides. Molecules. 2018;23:29–43. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.P., Hayasaka Y., Tyler M.J., Williams B.D. βcaryophyllene in the skin secretion of the Australian green tree frog, Litoria caerulea: an investigation of dietary sources. Aust. J. Zool. 2004;52:521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Starnberger I., Poth D., Saradhi Peram P., Schulz S., Vences M., Knudsen J., Barej M.F., Rodel M.O., Walzl M., Hodl W. Take time to smell the frogs: vocal sac glands of reed frogs (Anura: Hyperoliidae) contain species-specific chemical cocktails. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2013;110:828–838. doi: 10.1111/bij.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins R.C., Cohen N.W. Princeton University Press; New Jersey, West Sussex: 1997. A Natural History of Amphibians. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.H. University of Kansas Press; Lawrence, Kansas, USA: 1968. Caecilians of the World: A Taxonomic Review. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo R.C., Jared C. Cutaneous granular glands and amphibian venoms. Comparative Biochem. Physiol. - Part A. 1995;111:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- www.amphibiaweb.org, 8th March, 2019.

- Wake M.H. Another scaled caecilian (Gymnophiona: Typhlonectidae) Herpetologica. 1975;31:134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wake M.H., Nygren K.M. Variation in scales in Dermophis mexicanus (Amphibia: Gymnophiona): Are scales of systematic utility? Fieldiana. 1987;1378:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T.A., Larsen J.H., Jr. New function for the granular skin glands of the eastern long-toed salamander, Ambystoma macrodactylum columbianum. J. Exp. Zool. 1986;239:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Witalmska L.G., Kubiczek U. The structure of the skin of the tree frog (Hyla arboreaarborea L.) Annals of Anatomy. 1998;180:237–246. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(98)80080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt T.D. Cambrigde University Press. ISBI; 2003. Pheromones and Animal Behaviour, Communication by Smell and Taste. [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: Isolation, characterization of two active forms, and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1987;84:5449–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylberberg L., Castanet J., de Ricqles A. Structure of the dermal scales in Gymnophiona (Amphibia) J. Morphol. 1980;165:41–54. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051650105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylberberg L., Wake M.H. Structure of the scales of Dermophis and Microcaecilia (Amphibia: Gymnophiona), and a comparison to dermal ossifications of other vertebrates. J. Morphol. 1990;206:25–43. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052060104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]