Abstract

Cell-free mitochondrial DNA (cfmtDNA) is detectable in almost all human body fluids and has been associated with the onset and progression of several complex traits. In-life assessments indicate that reduced cfmtDNA is a feature of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. However, whether this feature is conserved across all neurodegenerative diseases and how it relates to the neurodegenerative processes remains unclear. In this study, we assessed the levels of ventricular cerebrospinal fluid-cfmtDNA (vCSF-cfmtDNA) in a diverse group of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) to determine if the in-life observations of reduced cfmtDNA seen in lumbar CSF translated to the post-mortem ventricular CSF. To investigate further, we compared vCSF-cfmtDNA levels to known protein markers of neurodegeneration, synaptic vesicles and mitochondrial integrity. Our data indicate that reduced vCSF-cfmtDNA is a feature specific to Parkinson’s and appears consistent throughout the disease course. Interestingly, we observed increased vCSF-cfmtDNA in the more neuropathologically severe NDD cases, but no association to protein markers of neurodegeneration, suggesting that vCSF-cfmtDNA release is more complex than mere cellular debris produced following neuronal death. We conclude that vCSF-cfmtDNA is reduced in PD, but not other NDDs, and appears to correlate to pathology. Although its utility as a prognostic biomarker is limited, our data indicate that higher levels of vCSF-cfmtDNA is associated with more severe clinical presentations; suggesting that it is associated with the neurodegenerative process. However, as vCSF-cfmtDNA does not appear to correlate to established indicators of neurodegeneration or indeed indicators of mitochondrial mass, further work to elucidate its exact role is needed.

Subject terms: Neurodegeneration, Neurodegenerative diseases

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disease (NDD) is an umbrella term that can be used to describe a diverse group of incurable nervous system disorders characterised by progressive loss of neuronal function and an overlapping spectrum of clinical phenotypes. The specific aetiology of many NDDs is complex and risk factors are multifactorial1,2, although there are often shared processes and pathological mechanisms3, such as the aggregation of misfolded proteins, proteotoxic stress and mitochondrial dysfunction4. NDDs can be difficult to diagnose and reliable biomarkers are needed to support early clinical diagnosis, to facilitate the delivery of effective treatments and improve patient welfare. Although some fluid-based biomarkers are established, for example, CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), biomarkers for other NDDs such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) have limited sensitivity and specificity5.

Circulating free nuclear DNA (cfDNA) was first identified in 19486, but rose to prominence as a biomarker of cancer in the 1970s7. Since then, cfDNA levels have been linked to a diverse range of phenotypes including sepsis8, myocardial infarction9 and autoimmune disease10. More recently, research has demonstrated an association between cell-free-mitochondrial DNA (cfmtDNA) and several complex traits11–23, particularly neurological and neurodegenerative diseases such as PD24,25, AD26,27 and multiple sclerosis (MS)14,28. Its stability in extracellular fluids such as plasma, serum and cerebrospinal fluid has led many studies to suggest that cfmtDNA has utility as a biomarker of disease onset and progression.

However, there remain several unresolved issues. For example, there is no convincing biological explanation for the differential cfmtDNA levels seen in NDDs. Various hypotheses have been suggested, such as that cfmtDNA may be a product of either apoptotic or necrotic cell death29,30, the result of active expulsion during increased oxidative or metabolic stress, where it acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern molecule (DAMP)31, or a product of organellar trafficking between cells in a bid for cell viability32. Thus, it might be expected that cfmtDNA would be elevated in diseases that are associated with broad cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, for NDDs at least, cfmtDNA is typically reduced compared to controls24–28. Further, few studies have shown correlations between cfmtDNA and the clinical and neurodegenerative hallmarks of disease. Whilst this does not necessarily diminish the usefulness of cfmtDNA as a biomarker, understanding the links between cfmtDNA and the neurodegenerative processes could improve our understanding of the pathology of NDDs. In the brain, cfmtDNA is likely to arise from the ependymal cells in the choroid plexus (CP), an area with abundant mitochondrial content33, specifically localised at the apical brush border34. Beyond AD35, the CP is not typically subject to gross neurodegeneration in NDD but does exhibit biological and pathophysiological changes associated with ageing and age-related disease36, including reduced CSF production and turnover, increased lipid (Biondi bodies) and protein (Aβ and α-synuclein) aggregates and reduced metabolic and enzymatic activity35,36. Furthermore, the CP appears to be particularly sensitive to mitochondrial dysfunction (a component of several NDDs26,28,37) commonly exhibiting physiological and anatomical changes in patients with Kearns-Sayre Syndrome38 and Leigh Syndrome39. Thus, although not directly implicated in NDD, the CP may also reflect disease-related changes within the CNS environment.

Here, to both expand upon the published observations in AD, PD and progressive MS and correlate cfmtDNA levels to established hallmarks of neurodegeneration, we assessed cfmtDNA levels in a large cohort of post-mortem ventricular CSF samples from a spectrum of NDDs.

Results

vCSF-cfmtDNA is reduced in PD, but not other NDDs

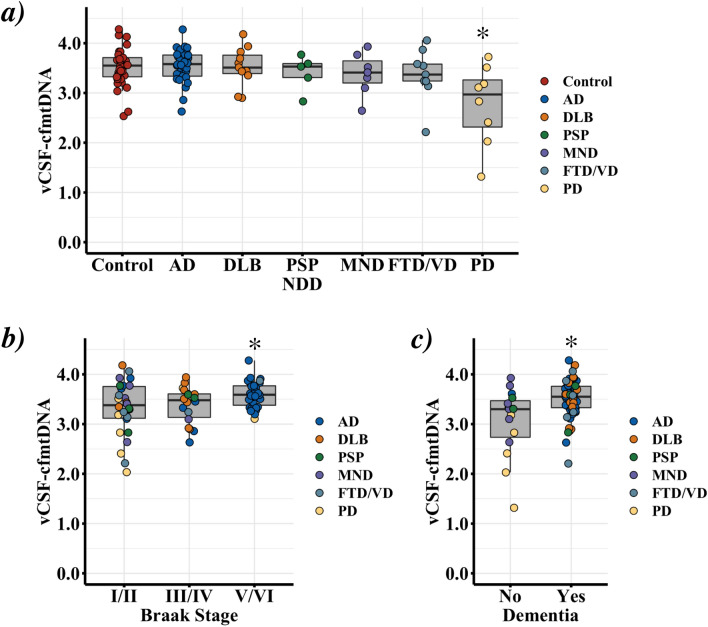

Similar to our previous cell-free mtDNA (cfmtDNA) work on lumbar CSF in PD37, we observed a significant reduction of ventricular CSF cfmtDNA (vCSF-cfmtDNA) in PD cases compared to controls (Fig. 1a, Dunnett’s p = 1.1 × 10−4). However, we observed no significant difference in vCSF-cfmtDNA levels between any other NDD group and controls (Dunnett’s p > 0.05, Fig. 1a) or when NDD patients were grouped and compared to controls (SFigure 1, TTEST p > 0.05). We also found no correlation between age of onset or disease duration and vCSF-cfmtDNA (r2 < 0.2, p < 0.05) (SFigures 2 and 3). We found no correlation between vCSF-cfmtDNA and postmortem delay when analysed as groups seperately or when combined.

Figure 1.

Comparison of vCSF-cfmtDNA levels in NDDs and matched controls. Boxplots of vCSF-cfmtDNA levels in NDD, showing vCSF-cfmtDNA levels in (a) each NDD and matched controls, (b) NDDs grouped and stratified by tau-Braak Stage and (c) NDDs stratified by dementia status. Where AD = Alzheimer’s Disease, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, MND = motor neuron disease, FTD/VD = frontotemporal lobar dementia/vascular dementia and PD = Parkinson’s disease. Boxes show median (thick line), 25th and 75th percentile and whiskers show 95% confidence interval. *indicates significance at p < 0.05 using ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (a, with control as reference & c, with I/II as reference) and Student’s TTEST of yes versus no (b).

vCSF-cfmtDNA is increased in patients exhibiting neocortical pathology

To assess the links between vCSF-cfmtDNA and neurodegenerative disease, we next compared vCSF-cfmtDNA levels to NDD cases stratified by tau pathology Braak staging40,41. We observed a significant correlation between Braak stage (I to VI) and vCSF-cfmtDNA levels (p = 0.028, Pearson’s correlation = 0.31). To simultaneously increase statistical power, and perform a focused regional analysis, we grouped our analysis into three neuropathological regions; early entorhinal (Braak I/II), a limbic (Braak III/IV), and a late neocortical (Braak V/VI) stage40,41. This stratification indicated patients with neocortical pathology showed significantly higher vCSF-cfmtDNA than patients with stage I/II pathology (Dunnett’s p < 0.05, Fig. 1b). It should be noted that this effect appears to be driven by AD patients (31/33 or 94% of individuals with Braak V/VI were AD).

vCSF-cfmtDNA is increased in patients with dementia

Around 80% of NDD patients (n = 65) were diagnosed with dementia before death. Similar to studies in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease42 and AD dementia27, we observed significantly higher vCSF-cfmtDNA levels in patients diagnosed with dementia when compared to non-demented cases (TTEST p = 0.024, Fig. 1c). Unlike the elevation of vCSF-cfmtDNA seen in Braak V/VI, where the subset of samples were largely AD cases, demented cases were a cross-section of the NDD cohort (38 AD, 11 DLB, 9 FTD/VD, 3 PD, 3 PSP and 1 MND), indicating that this result is somewhat independent of regional tau pathology.

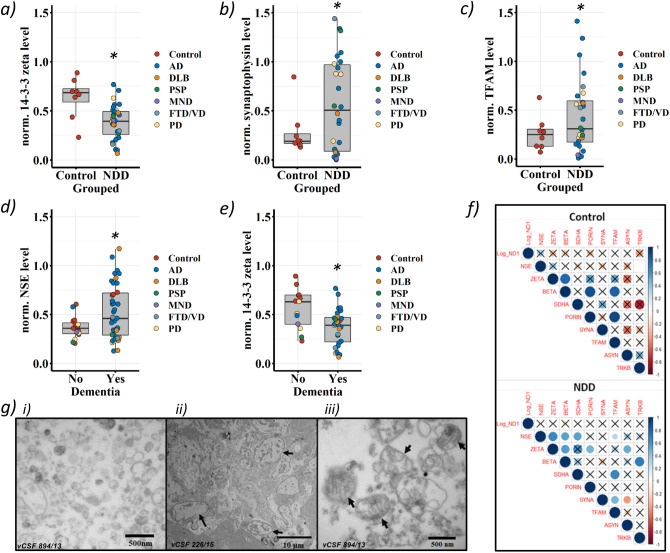

Neurodegenerative protein markers associate with NDD but do not correlate to vCSF-cfmtDNA levels

To further assess the links between vCSF-cfmtDNA and neurodegeneration we compared cfmtDNA levels to the abundance of CSF protein markers of neurodegeneration43,44, including neuron-specific enolase (NSE)45,46, 14–3-3 zeta and 14–3-3 beta47, alpha-synuclein48,49 and tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TRKB)50,51. To investigate potential associations with mitochondrial debris, extracellular and/or synaptic vesicles, vCSF-cfmtDNA was compared to the levels of the most abundant synaptic vesicle membrane protein synaptophysin52–54 and mitochondrial markers: SDHA (an inner mitochondrial membrane marker)55, TFAM (a mitochondrial transcription factor, the expression of which often reflects mtDNA level)56 and porin (to investigate mitochondrial mass)57.

We compared protein levels between each NDD and controls, revealing significant associations between 14–3-3 zeta protein and AD, DLB and FTD/VD cases, synaptophysin protein and PD, DLB, FTD/VD and PSP cases, TFAM protein and DLB and FTD/VD cases and 14–3-3 beta and TRKB proteins with PD cases (STable 1a). However, 95% confidence intervals showed great variability within disease groups which may be reflective of modest sample sizes. Thus, to improve statistical power, we combined all NDDs into one group and compared the protein levels to controls (STable 1b).

Although generally, vCSF markers of neurodegeneration were reduced in combined NDD cases compared to controls (STable 1b), only 14–3-3 zeta reached statistical significance (TTEST p = 0.011, Fig. 2a and STable 1b). Next, we compared synaptophysin, a synaptic vesicle marker58, between combined NDD cases and controls. Synaptophysin was significantly elevated in NDD cases compared to controls (TTEST p = 0.001) (Fig. 2b and Stable 1b). Finally, we observed no significant association between SDHA or porin and NDD (STable 1b), although TFAM levels were elevated in NDD cases compared to controls (TTEST p = 0.006) (Fig. 2c and STable 1b).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of neurodegenerative protein markers and vCSF-cfmtDNA in NDDs and matched controls. Boxplots of vCSF protein levels, showing, (a) 14–3-3 zeta, (b) synaptophysin and (c) TFAM protein levels in combined NDDs and matched controls. (d) and (e) shows NSE and 14–3-3 zeta protein levels respectively in combined NDDs stratified by the in-life diagnosis of dementia. Boxes show median (thick line), 25th and 75th percentile and whiskers show 95% confidence interval. *indicates significance at p < 0.05 Student’s TTEST. (f) Correlograms of vCSF-cfmtDNA level and protein levels in controls (upper) and combined NDDs (lower). Where, colour intensity depicts r2 and X indicates p > 0.05, Log_ND1 = vCSF-cfmtDNA, NSE = neuron specific enolase, ZETA/BETA = 14–3-3 zeta/beta, SDHA = succinate dehydrogenase, SYNA = synaptophysin, TFAM = transcription factor A, mitochondrial, ASYN = alpha synuclein, TRKB = tropomyosin receptor kinase B. (g) SEM images of vCSF pellets, indicating: (i) vesicular-like structures, (ii) proteinaceous material and (ii-iii) potential mitochondria-like structures (black arrows).

Stratification of cases by the diagnosis of dementia revealed both a significant elevation of NSE (TTEST p = 0.038, Fig. 2d and STable 2a) and a significant reduction of 14–3-3 zeta in NDD cases with dementia when compared to NDD cases without dementia (TTEST p = 0.006, Fig. 2e and STable 2a). However, we observed no significant association between protein levels and Braak staging (STable 2b).

We did observe several novel interprotein correlations (Fig. 2f). Interestingly, the 14–3-3 proteins, zeta and beta, appear correlated (r2 > 0.5) in both NDD cases and controls. However, all other interprotein correlations appeared dependent on disease status. For example, NSE appears correlated (p < 0.05) to 14–3-3 zeta (r2 = 0.7), 14–3-3 beta (r2 = 0.5), SDHA (r2 = 0.5) and TFAM (r2 = 0.3) in NDD cases, but not controls. In NDD cases only, synaptophysin correlated (p < 0.05) to TFAM (r2 = 0.5) and alpha synuclein (r2 = -0.4), whereas in control only 14–3-3 beta correlated (p < 0.05) to porin (r2 = 0.9) and TFAM (r2 = 0.8). Whilst mitochondrial proteins SDHA and TFAM (r2 = 0.7, p < 0.05) correlated in NDD cases, porin and TFAM (r2 = 0.9, p < 0.05) correlated in controls.

Although several proteins were associated with NDD and dementia, we found no significant correlations between vCSF-cfmtDNA and protein levels in either combined NDD cases or controls (Fig. 2f), when NDDs were separated (STable 3), or when individuals were grouped by dementia status (STable 3).

Electron microscopy of the vCSF indicates extracellular mitochondria-like structures

Recent work has suggested that, in addition to cfmtDNA, intact mitochondria can be observed in extracellular fluids such as plasma59. To investigate this in vCSF, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of two vCSF-cfmtDNA samples with large volumes of vCSF available (> 500 µl). TEM indicated the presence of abundant proteinaceous material (Fig. 2g) and various small and larger vesicular structures, potentially microvesicles, (Fig. 2gi), but no cellular debris. Cell-free mitochondria-like structures could be detected with double membranes and remnants of cristae like morphology, however, these were scarce and showed gross morphological changes and partial membrane degradation (Fig. 2gii-iii).

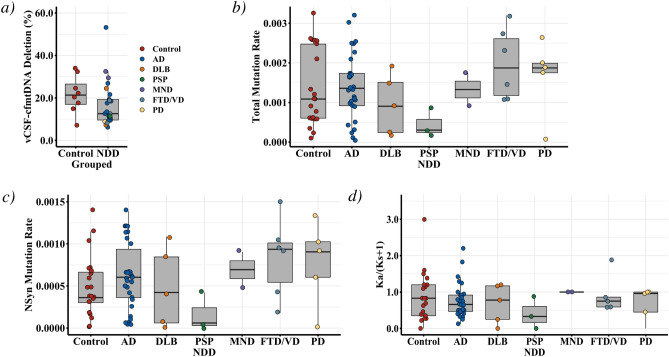

vCSF-cfmtDNA circulates as intact genomes, with low deletion and heteroplasmy levels

We next assessed the integrity of vCSF-cfmtDNA using both qPCR, to measure mtDNA deletion levels28, and next-generation-sequencing (NGS), to assess mtDNA mutational load28.

Only 31 samples (27%), 23 (29%) NDD and 8 controls (23%), harboured mtDNA deletions above the established detection threshold of 10%60, suggesting that in the majority of samples (73%) vCSF-cfmtDNA is intact and full length. Although mtDNA deletion levels appeared lower in NDD cases compared to controls (Fig. 3a) this did not reach statistical significance (TTEST p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Analysis on vCSF-cfmtDNA integrity in NDDs and matched controls. Boxplots of vCSF-cfmtDNA integrity in NDD, showing (a) vCSF-cfmtDNA deletion level in NDDs and matched controls, (b) the comparative total vCSF-cfmtDNA heteroplasmic mutation rate in each NDD and matched controls, (c) the comparative non-synonymous vCSF-cfmtDNA heteroplasmic mutation rate in each NDD and matched controls and (d) the vCSF-cfmtDNA Ka/Ks(+ 1) for in each NDD and matched controls. Where AD = Alzheimer’s Disease, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, MND = motor neuron disease, FTD/VD = frontotemporal lobar dementia/vascular dementia and PD = Parkinson’s disease. Boxes show median, 25th and 75th percentile and whiskers show 95% confidence interval.

Next, we performed NGS of vCSF-cfmtDNA from 72 samples (51 cases, or 71%, and 21 controls, 29%). Although we were able to detect heteroplasmic variants (average = 23.2 in NDD and 22.3 in controls), we observed no significant difference between NDDs and controls (Dunnett’s > 0.05) when analysed as total heteroplasmic mutation rate (Fig. 3b) or when comparing non-synonymous heteroplasmic (i.e. putatively functional) variation (Fig. 3c). Combining NDD cases, to improve statistical power, and comparing mutation rates to controls also failed to identify a significant difference (TTEST p > 0.05, SFigure 4a and b). In previous work28, we had observed an imbalance in the Ka/Ks ratio (an indication of variant selective bias) of vCSF-cfmtDNA between progressive MS patients and controls However, we observed no significant difference in the Ka/Ks ratio of vCSF-cfmtDNA in NDDs compared to controls when analysed individually (Fig. 3d, Dunnett’s > 0.05) or when grouped as NDD disease (SFigure 4c TTEST p > 0.05).

Discussion

Several studies have associated cell-free mtDNA (cfmtDNA) with human disease11–23, particularly neurodegenerative disease (NDD)26,28,37. Whilst these studies were typically aimed at identifying biomarkers of disease, they were unable to link cfmtDNA levels to pathology. In this study, we measured cfmtDNA in post-mortem ventricular CSF (vCSF), correlating vCSF-cfmtDNA levels to established markers of neurodegeneration to determine if the reported in-life cfmtDNA measurements in lumbar CSF would translate through to vCSF mtDNA levels and neuropathological assessment.

Our results indicate that, in line with our earlier observations in lumbar CSF25,61, vCSF-cfmtDNA is reduced in PD compared to controls, and this phenomenon appears to be specific to PD cases, rather than a feature of other NDDs. However, our data suggest that the relationship between vCSF-cfmtDNA and NDD may be more complex, possibly reflecting the diverse and multifaceted underlying pathoetiology of each disease. Intriguingly, a subsequent analysis indicates that elevated vCSF-cfmtDNA is associated with the degree of neuropathology, with higher levels of vCSF-cfmtDNA associated with late neocortical tau aggregations (Braak stage 5/6) and dementia.

In PD, the reduced vCSF-cfmtDNA we observed suggests that reduced cfmtDNA persists throughout the disease course with post-mortem vCSF-cfmtDNA levels comparable to those we observed in early-stage PD lumbar CSF25,37. How this relates to the neurodegenerative process in PD remains still unclear as we found no correlation between vCSF-cfmtDNA and neurodegenerative protein markers. However, the answers may reside in the relationship between cfmtDNA and neuronal mtDNA copy number. Previous work has shown that neuronal mtDNA copy-number is reduced in PD24,62, particularly in dopaminergic neurons63, and is correlated to mitochondrial dysfunction62. Thus, the reduced vCSF-cfmtDNA in PD may reflect an already depleted cellular mtDNA pool, with PD simply having less mtDNA to release. Further, reduced vCSF-cfmtDNA in PD may be a reflection of the treatment that PD patients have received, as our recent analysis indicates that reduced vCSF-cfmtDNA in PD correlates to levodopa effective daily dose25. Thus, as treatment in the latter stages of PD typically moves from symptom relief and prevention of motor symptoms (i.e. L-dopa) towards non-motor treatments and palliative care64, it is possible that the reduction of vCSF-cfmtDNA occurs early in the disease course and, for the majority of PD cases, remains reduced. However, this can only be tested in a longitudinal study that allows in-life lumbar CSF-cfmtDNA levels to be correlated with post-mortem vCSF-cfmtDNA levels.

Unlike PD, we did not observe a significant reduction in vCSF-cfmtDNA in the other NDDs.

Previous literature26 suggests that ‘probable’ AD cases (defined as those with low CSF amyloid beta1-42 and elevated tau levels) and high-risk for AD individuals (defined as asymptomatic but with low CSF amyloid beta1-42) exhibit significantly lower lumbar CSF cfmtDNA than controls. Conversely, a study of well-characterised AD patients reports significantly higher lumbar CSF cfmtDNA level than that of cognitively healthy controls27.

In our study, AD vCSF-cfmtDNA levels were not significantly different from matched controls. However, we did observe increased vCSF-cfmtDNA in NDD cases who exhibited extensive neocortical involvement (Braak V/VI40,41 when compared to Braak stages I/II) and individuals who had progressed to dementia. These results are likely self-confirmatory as AD cases made up 93% and 59% of all cases from both groups respectively (31/33 Braak stage V/VI cases and 38/65 dementia cases). When taken together, this suggests that in AD cfmtDNA levels may rise with disease severity and neuropathology, beginning at markedly low levels in pre-clinical stages and rising to exceed that of controls when dementia becomes severely debilitating and there is widespread neocortical pathology. However, longitudinal studies in AD would be needed to confirm this.

Elevated cfmtDNA has been observed in patients with traumatic brain injury65, relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis14 and Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis66, suggesting that elevated cfmtDNA may be a component of the inflammatory response14,65,66. The innate immune system is involved in the pathoetiology of many NDDs67 and can be activated by mtDNA. Circulating cfmtDNA is a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule that can trigger the antimicrobial and inflammatory response68 after shock, injury68, infection69 and cancer70. Thus, given the increased neuroinflammation observed in NDDs71, our data suggest that the increase in vCSF-cfmtDNA we observed in chronic NDD may be a component of this response and may be a component of the pathogenesis of NDD and future work should attempt to link cfmtDNA to CSF markers of neuroinflammation.

To investigate the links between cfmtDNA and neurodegeneration further, we compared vCSF-cfmtDNA levels to the levels of reported CSF protein markers of NDD. Similar to others72, we hypothesised that vCSF-cfmtDNA levels would correlate to indicators of neuronal cell death, which may, in turn, explain the origins of vCSF-cfmtDNA. However, although we observed associations between protein levels and disease, we did not observe associations between these proteins and vCSF-cfmtDNA. This suggests that vCSF-cfmtDNA levels are not wholly coupled to apoptosis or derived from cellular debris. It must be noted, however, that we chose these proteins based on a priori assumption regarding their role in disease pathogenesis or pathology. Thus, further work should utilise an unbiased proteomic approach (i.e. mass spectrometry), potentially establishing novel protein interactions and further developing the understanding of underlying mechanisms involved in this biological phenomenon.

Previous work in serum indicates that cfmtDNA may be derived from circulating intact mitochondria59 and work in C. Elegans identified mitochondria in extracellular vesicles extruded under neurotoxic stress73. Similarly, we were able to detect the presence of cell-free mitochondria-like structures within vCSF. However, unlike the ‘in-life’ observations of intact and functionally competent mitochondrial made by Al Amir Dache et al. (2020), the mitochondrial structures we identified in NDD vCSF were sparse, grossly degraded and lacking defined membranes and cristae shape. Given that mitochondrial dysfunction is a component of many NDDs4,62,63, mitochondrial expulsion may be linked to pre-existing dysfunction, but it is also possible that the degraded morphology is a result of the post-mortem nature of the vCSF. To investigate further, we measured the abundance of the mitochondrial proteins SHDA55, TFAM56 and porin57. Although these mitochondrial markers were detectable in both NDD and controls they did not correlate to vCSF-cfmtDNA, further suggesting vCSF-cfmtDNA levels are independent of cell-free mitochondrion abundance. TEM of post-mortem CSF suggested the presence of extracellular vesicles within the vCSF, in line with similar reports74,75, which may point towards a possibility of an active release of cellular mitochondria to CSF via the extracellular vesicles route. Elevated CSF synaptophysin a synaptic vesicle marker, has been observed in patients with traumatic brain inury75, and its release into CSF is associated with neuronal cytotoxicity76. Similarly, in our study synaptophysin was significantly enriched in vCSF of NDDs, however, we found no correlation between vCSF-cfmtDNA and synaptophysin protein levels. Taken together, these data suggest that further work, specifically focusing on vCSF extracellular vesicles and quantifying their ccf-mtDNA content, could be vital in elucidating the origin and release of ccf-mtDNA.

MtDNA lesions and mutations are a hallmark of many NDDs77, with high levels of mtDNA deletions and somatic (heteroplasmic) mutations identified in disease-specific brain regions of PD78,79 and AD80 patients. Similar to previous work81, we used qPCR and NGS to interrogate the integrity of vCSF-cfmtDNA under the hypothesis that increased vCSF-cfmtDNA release linked to mtDNA maintenance mechanism, where mutated mtDNA is expelled from cells to maintain a ‘wild-type’ mtDNA pool. Our analysis indicates that although mtDNA deletions and point mutations were present in NDD vCSF-cfmtDNA, they were not significantly more frequent than in controls. Whilst this does not necessarily negate the hypothesis that vCSF-cfmtDNA is a mechanism for maintaining a healthy cellular mtDNA pool, our results do suggest that this mechanism is independent of disease status. However, it must be noted that a potential reason for this could be neuronal ‘survivor bias’; where, due to the end-stage of disease, only the cells with low-level mtDNA defects remain. This is somewhat supported by brain mtDNA heteroplasmy analysis82, whereby post-mortem, end-stage NDDs and controls show similar brain mtDNA heteroplasmy.

Our work is not without limitations. Firstly, the availability of post-mortem vCSF samples is limited and future work should expand the cohort sizes, particularly of non-AD NDDs. Secondly, although we were able to identify several protein-NDD associations, we were unable to link vCSF-cfmtDNA to established hallmarks of neurodegeneration. Thus, future work should take a more unbiased proteomics approach, for example using mass-spectrometry to identify all proteins with the vCSF. Finally, as discussed, neuroinflammation is demonstrated to be a key feature of many NDDs, most likely contributing to the pathogenesis of these disorders (as reviewed in83). Interestingly, cfmtDNA is also implicated in the inflammatory process, and previous studies have shown direct interplay between levels of this inflammatory molecule and important inflammatory cytokines in both human plasma84 and CSF66. This is a particularly crucial area for future study as it may reveal functional attributes of the cfmtDNA and its potential role in the mediation of the immune response in NDD.

Conclusions

We conclude that vCSF-cfmtDNA is reduced in PD, but not other NDDs. Although its utility as a prognostic biomarker is severely limited, our data indicate that higher levels of vCSF-cfmtDNA are associated with more severe clinical presentations; suggesting that it plays a role in the neurogenerative process. However, as vCSF-cfmtDNA does not appear to correlate to established indicators of neurodegeneration or indeed indicators of mitochondrial mass, further work to elucidate its exact role is needed.

Methodology

Ventricular CSF sample cohort

We used 115 ventricular cerebrospinal fluid (vCSF) samples, obtained from the Newcastle Brain Tissue Resource (NBTR) and the Imperial College Tissue Bank (80 Neurodegenerative disease cases: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) = 40, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) = 11, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) = 5, motor neurone disease (MND) = 7, frontal temporal/vascular dementia (FTD/VD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) = 8, and 35 controls). vCSF was collected post-mortem from hemisected brains and immediately stored at -80 °C in polypropylene cryovials, which do not influence biomarker outcome85. Samples were prepared via methods described previously86,87. Briefly, vCSF was centrifuged (2000 g for 10 min) at room temperature, aliquoted into CSF collection tubes and stored upright at − 80 °C. All cases were confirmed in life by a local clinician and re-assessed neuropathologically post-mortem. All controls were negative for hallmarks of neurodegeneration or inflammation.

VCSF-cfmtDNA quantification

Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA was quantified by established triplex Taqman qPCR28,60,87. VCSF-cfmtDNA level was calculated as the absolute measurement of MTND1, derived from a triplicated standard curve and expressed as copies per 1 µl of CSF. mtDNA deletion level was expressed as a ratio of MTND1 to MTND4 as described previously28,60,87.

VCSF protein analysis

Protein markers of neuronal damage (neuron specific enolase, NSE; 14–3-3 beta; 14–3-3 zeta; tropomyosin receptor kinase B, Trkb), the synaptic vesicle membrane (synaptophysin) and mitochondrial components (SDHA; Porin; Tfam), were measured in all samples with sufficient vCSF (42 NDD patients; minimum in each disease group = AD 18, DLB 4, MND 1, FTD/VD 2, PSP 2, PD 5 and 14 controls; minimum 8), using western blot. Protein levels were normalised to total protein level measured with BLOT-FastStain™. Alpha-synuclein expression was measured by ELISA (LEGEND MAX™ Human alpha-synuclein ELISA kit) in the same samples as above, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

VCSF transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron microscopy was performed on a subset of vCSF samples. Briefly, vCSF was pelleted, fixed, dehydrated and then embedded into Taab medium epoxy resin, as described previously88. After polymerisation, ultrathin Sects. (70 nm) were collected, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and then imaged on a Philips CM100 Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM).

vCSF-cfmtDNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

Deep sequencing was performed on vCSF-cfmtDNA extracts from a subset (where volume and mtDNA concentration permitted), of vCSF samples (53 NDD patients and 21 controls) as described previously28,89. Briefly, mtDNA was extracted from vCSF using Ultrapure™ and ethanol precipitation, as per manufacturers guidelines, and enriched using three amplicon long-range PCR, covering the entire mtDNA genome. PCR products were purified, pooled and prepared using Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit. Sequencing was performed using the Illumina Miseq v3.0 platform in paired-end, 250 bp reads. Post-run FASTQ files were analysed using an established in-house bioinformatics pipeline, as described previously28.

Statistical analysis

Normality of vCSF-cfmtDNA distributions were assessed by Shapiro-Wilks and could not be rejected at the 0.05 level. Thus, all vCSF-cfmtDNA levels are expressed as log [10] copy-number per microliter. Data were analysed in R (v4.0)90 using data appropriate tests (detailed in the text). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All tests were two-tailed with α = 0.05. Correlograms of protein levels were created using corrplot (v0.84) in R.

Ethics approval

Donors or next of kin provided informed consent to donate tissue and all procedures were approved by the local UK National Health Service Research Ethics Committee. All procedures were approved by each Local Research Ethics Committee and appropriate informed consent was obtained from donors or next of kin for sample donation. Newcastle Brain Tissue Resource has been approved as a Research Tissue Bank by NRES Committee North East (Ref. No 08/H0906/136 + 5) and Parkinson's UK Brain Bank at the Imperial College London has been approved as a Research Tissue Bank by the Wales Research Ethics Committee (Ref. No. 08/MRE09/31 + 5). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

All data, genetic and proteomic, is available upon request.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the patients, who donated their tissues and samples, and their respective carers. The authors also thank the Newcastle Tissue Brain Resource (UK), for their assistance with the tissue selection and use, and Dr Kath White from the Newcastle University EM Research Service, for her guidance with the EM data. GH receives funding from the Wellcome PPMI and the Wellcome Trust (203105/Z/16/Z) Michael J Fox (ID-15643) Foundation and this work was funded in part by Parkinson’s UK (F-1202).

Author contributions

G.H., H.L. and A.P. conceived the project. H.L. and A.P. performed all of the vCSF-cfmtDNA experimental work. H.L. and M.K.A. designed and carried out the vCSF protein analysis. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72190-5.

References

- 1.Mandemakers W, Morais VA, De Strooper B. A cell biological perspective on mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:1707–1716. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jellinger KA. Recent advances in our understanding of neurodegeneration. J. Neural Transm. 2009;116:1111–1162. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan L, Cookson MR, Petrucelli L, La Spada AR. Converging pathways in neurodegeneration, from genetics to mechanisms. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:1300–1309. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0237-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golpich M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis and treatment. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017;23:5–22. doi: 10.1111/cns.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cova I, Priori A. Diagnostic biomarkers for Parkinson's disease at a glance: where are we? J. Neural Transm. 2018;125:1417–1432. doi: 10.1007/s00702-018-1910-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandel P, Metais P. Not Available. C. R. Seances Soc. Biol. Fil. 1948;142:241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leon SA, Shapiro B, Sklaroff DM, Yaros MJ. Free DNA in the serum of cancer patients and the effect of therapy. Cancer Res. 1977;37:646–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes A, Wort SJ, Thomas H, Collinson P, Bennett ED. Plasma DNA concentration as a predictor of mortality and sepsis in critically ill patients. Crit. Care. 2006;10:R60. doi: 10.1186/cc4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rainer TH, et al. Plasma beta-globin DNA as a prognostic marker in chest pain patients. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2006;368:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duvvuri B, Lood C. Cell-free DNA as a biomarker in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:502. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, et al. Circulating cell free mitochondrial DNA is a biomarker in the development of coronary heart disease in the patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Lab. 2015;61:661–667. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2014.141132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarado-Vasquez N. Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA as the probable inducer of early endothelial dysfunction in the prediabetic patient. Exp. Gerontol. 2015;69:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindqvist, D., et al. Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA, but not leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number, is elevated in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Varhaug KN, et al. Increased levels of cell-free mitochondrial DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mitochondrion. 2017;34:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudakov NP, et al. Level of blood cell-free circulating mitochondrial DNA as a novel biomarker of acute myocardial ischemia. Biochem. Mosc. 2015;80:1387–1392. doi: 10.1134/S000629791510020X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantham S, Srivastava AK, Gulati S, Rajeswari MR. Plasma circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA in the assessment of Friedreich's ataxia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016;365:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Santiago J, et al. Cell-free mitochondrial DNA in CSF is associated with early viral rebound, inflammation, and severity of neurocognitive deficits in HIV infection. J. Neurovirol. 2016;22:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0384-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Santiago J, et al. Increased cell-free mitochondrial DNA is a marker of ongoing inflammation and better neurocognitive function in virologically suppressed HIV-infected individuals. J. Neurovirol. 2017;23:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0497-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry W, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirate-derived preclinical pancreatic cancer models reveal panitumumab sensitivity in KRAS wild-type tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;140:2331–2343. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu HB, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of circulating cell-free genomic and mitochondrial DNA fragments in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2016;452:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zachariah RR, et al. Levels of circulating cell-free nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in benign and malignant ovarian tumors. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;112:843–850. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181867bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohler C, et al. Levels of plasma circulating cell free nuclear and mitochondrial DNA as potential biomarkers for breast tumors. Mol. Cancer. 2009;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahmoud EH, Fawzy A, Ahmad OK, Ali AM. Plasma circulating cell-free nuclear and mitochondrial DNA as potential biomarkers in the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:8299–8305. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.18.8299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pyle A, et al. Reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number is a biomarker of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;38:216.e7–216.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowes H, Pyle A, Santibanez-Koref M, Hudson G. Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA levels in Parkinson's disease are influenced by treatment. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020;15:10. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00362-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podlesniy P, et al. Low cerebrospinal fluid concentration of mitochondrial DNA in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74:655–668. doi: 10.1002/ana.23955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cervera-Carles, L., et al. Cerebrospinal fluid mitochondrial DNA in the Alzheimer's disease continuum. Neurobiol Aging53, 192 e191–192 e194 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lowes, H., Pyle, A., Duddy, M. & Hudson, G. Cell-free mitochondrial DNA in progressive multiple sclerosis. Mitochondrion (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Bisharyan Y, Clark TG. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial extrusion in ciliated protozoa. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Mitochondrial DNA is released by shock and activates neutrophils via P38 map kinase. Shock. 2010;34:55–59. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cd8c08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkins HM, et al. Extracellular mitochondria and mitochondrial components act as damage-associated molecular pattern molecules in the mouse brain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2016;11:622–628. doi: 10.1007/s11481-016-9704-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torralba D, Baixauli F, Sanchez-Madrid F. Mitochondria know no boundaries: mechanisms and functions of intercellular mitochondrial transfer. Frontiers Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;4:107. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornford EM, Varesi JB, Hyman S, Damian RT, Raleigh MJ. Mitochondrial content of choroid plexus epithelium. Exp. Brain Res. 1997;116:399–405. doi: 10.1007/pl00005768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spector R, Keep RF, Robert Snodgrass S, Smith QR, Johanson CE. A balanced view of choroid plexus structure and function: focus on adult humans. Exp. Neurol. 2015;267:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balusu S, Brkic M, Libert C, Vandenbroucke RE. The choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid interface in Alzheimer's disease: more than just a barrier. Neural Regen. Res. 2016;11:534–537. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.180372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serot JM, Bene MC, Faure GC. Choroid plexus, aging of the brain, and Alzheimer's disease. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s515–521. doi: 10.2741/1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pyle A, et al. Reduced cerebrospinal fluid mitochondrial DNA is a biomarker for early-stage Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 2015;78:1000–1004. doi: 10.1002/ana.24515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanji K, Schon EA, DiMauro S, Bonilla E. Kearns-sayre syndrome: oncocytic transformation of choroid plexus epithelium. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000;178:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohama E, Ikuta F, Nakamura N. Mitochondrial abnormalities in choroid plexus of Leigh disease. Brain Dev. 1988;10:30–35. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(88)80042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, et al. Detection of cell-free mitochondrial DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of Creutzfeldt-Jakob patients. Front Neurol. 2019;10:645. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robey TT, Panegyres PK. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in neurodegenerative disorders. Future Neurol. 2019;14:FNL6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katayama T, et al. Molecular biomarkers of Parkinson disease and neurodegenerative disorders in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017;381:359–359. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haque A, Polcyn R, Matzelle D, Banik NL. New insights into the role of neuron-specific enolase in neuro-inflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuroprotection. Brain Sci. 2018;8:33. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8020033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt FM, Mergl R, Stach B, Jahn I, Schonknecht P. Elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid neuron-specific enolase (NSE), but not S100B in major depressive disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;16:106–113. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.952776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foote M, Zhou Y. 14-3-3 proteins in neurological disorders. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;3:152–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mollenhauer B, et al. Alpha-Synuclein and tau concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of patients presenting with parkinsonism: a cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:230–240. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohrfelt A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein in neurodegenerative disorders-a marker of synapse loss? Neurosci. Lett. 2009;450:332–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Everitt BJ, et al. The effects of excitotoxic lesions of the substantia innominata, ventral and dorsal globus pallidus on the acquisition and retention of a conditional visual discrimination: implications for cholinergic hypotheses of learning and memory. Neuroscience. 1987;22:441–469. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin W. Regulation of BDNF-TrkB signaling and potential therapeutic strategies for Parkinson's disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:257. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon SE, Chapman ER. Synaptophysin regulates the kinetics of synaptic vesicle endocytosis in central neurons. Neuron. 2011;70:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiedenmann B, Franke WW, Kuhn C, Moll R, Gould VE. Synaptophysin: a marker protein for neuroendocrine cells and neoplasms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:3500–3504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewczuk P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers for neurodegenerative dementias: an update of the Consensus of the Task Force on Biological Markers in Psychiatry of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. World J. Biol. Psychia. 2018;19:244–328. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1375556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuhlbrandt W. Structure and function of mitochondrial membrane protein complexes. BMC Biol. 2015;13:89. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0201-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, Kaufman BA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1819:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, et al. Investigation of mitochondrial biogenesis defects in single substantia nigra neurons using post-mortem human tissues. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020;134:104631. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewczuk P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers for neurodegenerative dementias: an update of the Consensus of the Task Force on Biological Markers in Psychiatry of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;19:244–328. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2017.1375556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al Amir Dache Z, et al. Blood contains circulating cell-free respiratory competent mitochondria. FASEB J. 2020;34:3616–3630. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901917RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grady JP, et al. Accurate measurement of mitochondrial DNA deletion level and copy number differences in human skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pyle A, et al. Reduced mitochondrial DNA is not a biomarker of depression in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2016;31:1923–1924. doi: 10.1002/mds.26825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dolle C, et al. Defective mitochondrial DNA homeostasis in the substantia nigra in Parkinson disease. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13548. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grunewald A, et al. Mitochondrial DNA depletion in respiratory chain-deficient parkinson disease neurons. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:366–378. doi: 10.1002/ana.24571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lokk J, Delbari A. Clinical aspects of palliative care in advanced Parkinson's disease. BMC Palliat. Care. 2012;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walko TD, 3rd, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid mitochondrial DNA: a novel DAMP in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Shock. 2014;41:499–503. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peng Y, et al. Cell-free mitochondrial DNA in the CSF: a potential prognostic biomarker of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:103. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amor S, Woodroofe MN. Innate and adaptive immune responses in neurodegeneration and repair. Immunology. 2014;141:287–291. doi: 10.1111/imm.12134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Q, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–U115. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakahira K, Hisata S, Choi AM. The roles of mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;23:1329–1350. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ellinger J, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA in serum: a universal diagnostic biomarker for patients with urological malignancies. Urol. Oncol. 2012;30:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker KA. Inflammation and neurodegeneration: chronicity matters. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;11:3–4. doi: 10.18632/aging.101704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aucamp J, Bronkhorst AJ, Badenhorst CPS, Pretorius PJ. The diverse origins of circulating cell-free DNA in the human body: a critical re-evaluation of the literature. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2018;93:1649–1683. doi: 10.1111/brv.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melentijevic I, et al. C. elegans neurons jettison protein aggregates and mitochondria under neurotoxic stress. Nature. 2017;542:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nature21362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Emelyanov A, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy of extracellular vesicles from cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0227949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manek R, et al. Protein biomarkers and neuroproteomics characterization of microvesicles/exosomes from human cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:6112–6128. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0821-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar D, Manek R, Raghavan V, Wang KK. Protein characterization of extracellular microvesicles/exosomes released from cytotoxin-challenged rat cerebrocortical mixed culture and mouse N2a cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:2112–2124. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Keogh MJ, Chinnery PF. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1847:1401–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Turnbull D. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease, aging, and neurodegeneration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:21–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coxhead, J., et al. Somatic mtDNA variation is an important component of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Aging38, 217 e211–217 e216 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Alzheimer's brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10726–10731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lowes H, Pyle A, Duddy M, Hudson G. Cell-free mitochondrial DNA in progressive multiple sclerosis. Mitochondrion. 2019;46:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wei W, et al. Mitochondrial DNA point mutations and relative copy number in 1363 disease and control human brains. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017;5:17. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0419-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen WW, Zhang X, Huang WJ. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases (Review) Mol. Med. Rep. 2016;13:3391–3396. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kageyama Y, et al. The relationship between circulating mitochondrial DNA and inflammatory cytokines in patients with major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;233:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teunissen CE, et al. A consensus protocol for the standardization of cerebrospinal fluid collection and biobanking. Neurology. 2009;73:1914–1922. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c47cc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mollenhauer B, et al. Direct quantification of CSF alpha-synuclein by ELISA and first cross-sectional study in patients with neurodegeneration. Exp. Neurol. 2008;213:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pyle, A., et al. Reduced CSF mitochondrial DNA is a biomarker for early-stage Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Chou SH, et al. Extracellular mitochondria in cerebrospinal fluid and neurological recovery after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2017;48:2231–2237. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coxhead J, et al. Somatic mtDNA variation is an important component of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2016;38(217):e211–217.e216. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data, genetic and proteomic, is available upon request.