THE STORY OF COVID-19

In December 2019, a sequence of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology appeared in Wuhan, China.1 The National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China later announced that a novel coronavirus, now named Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization, was responsible for the outbreak.2 The number of new cases is rising every day despite the variability of the documented cases among countries and regions, reaching more than 14 million confirmed patients worldwide with approximately 618,017 patient deaths up to the writing of this article.3

Fever, cough, and sore throat are the most common symptoms encountered among the patients with confirmed COVID-19. The spectrum of symptomatic COVID-19 ranges from mild respiratory symptoms to a severe form of pneumonia that requires mechanical ventilation and ends with progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome or multi-organ failure.4 The difference in the registered number of cases in each country depends largely on the number of individuals tested.

Until now, Egypt saw a slowly rising curve with approximately 89,745 confirmed cases and 4440 deaths through the time of writing this manuscript. This number of registered cases, despite its continued rise, did not yet reach critical numbers that could affect medical services.5 However, regulations are established in Egyptian hospitals to limit elective admissions and halt unnecessary interventions.

Because medical professionals followed strict precautions and guidelines in dealing with patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Wuhan, China, no registered patients with IBD in one center were infected with COVID-19. In this group of 318 patients with IBD—most of whom were on immunosuppressive therapy—strict precautions and proper handling of patients resulted in a good outcome.6

THE SITUATION REGARDING IBD IN EGYPT

Unlike for diseases such as hepatitis C virus and cancer, Egypt presents no formal registry for patients with IBD.7 In fact, IBD always seemed to be rare in the Middle East and Northern Africa. In Mediterranean countries, the prevalence of patients with IBD was estimated at 5 per 100,000 in urban areas.8 That low number of IBD cases is accompanied by a small number of studies reporting on IBD in Egypt.

However in the past few years, the incidence of IBD in Egypt has increased, possibly due in part to increased awareness.7 This can also be attributed to the fact that as countries become westernized, they show an increased incidence of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD).9

In their study, Esmat et al10 reported that most of their patients with UC presented with mild distal or left-sided colitis (approximately 85%), whereas 11.9% of the patients presented with a severe form of UC. This agrees to some extent with another study8 based on the endoscopic diagnosis of UC, which showed that 27% of patients presented with severe UC.

The extent and severity of the disease naturally exhibit an impact on its management and treatment, with treatment ranging from topical therapies (aminosalicylates [5-ASAs] and steroids) to systemic therapies (steroids, 5-ASA, immunomodulators such as azathioprine, biological therapy such as anti-TNF agents [eg, infliximab and adalimumab], anti-adhesion molecules such as vedolizumab, and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as ustekinumab), and finally surgical options. The drugs used in IBD management generally exhibit an immunosuppressant effect, which might be associated with side effects.7, 8

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF IBD DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a very high need for hospitalization for symptomatic cases. European hospitals started to intensively reduce elective activities to prepare for high numbers of COVID-19-related admissions.1 This demonstrates an effect on patients with diseases that require regular and continuous follow-up, including IBD patients.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is able to use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) proteins as an entry receptor to ACE2-expressing cells but not other cells.11 Evidence exists that ACE2 proteins are expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelia, presenting them as host cells.12 The continuous positive detection of the viral RNA from feces suggests that the infectious virions are secreted from the virus-infected gastrointestinal cells, and therefore, the feco-oral route should be considered.13

As of March 20, 2020, 15 cases of IBD with COVID-19 were reported in the United States.14 Different societies involved in the management of IBD issued expert opinions and interim guidelines for treatment and endoscopy to ensure adequate management of IBD patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. These included China,15 Italy,16 and the United States.17

The use of steroids may lead to uncontrolled sepsis and intercurrent infections.18 Infliximab therapy is associated with an increased incidence of respiratory infections and, particularly, the potential reactivation of tuberculosis. Common side effects of adalimumab include respiratory infections and sinusitis.19 This poses the question of whether an increased risk for COVID-19 infection, complications, and mortality exists among patients with IBD.15 That is in addition to the fact that the IBD itself could cause immune dysfunction, as different studies confirmed that CD, for example, may lead to immunodeficiency owing to a malfunction of macrophages and defective response to bacteria in the intestine.20

The economic and political situation imposed by the exponential increase in COVID-19 cases should also be taken into consideration. As mentioned previously, the nature of IBD and the fact that our knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 is still lacking, with new information arising each day, reveal the need for international guidance concerning IBD during the pandemic. Most societies with incidence of IBD have an agreement regarding the fact that the risk of COVID-19 infection is mostly not different between the general population and patients with IBD. They share the advice that all patients in stable remission should continue their therapies and delay all nonurgent medical procedures, including colonoscopies.15–17

Issued guidelines place special emphasis on the role of social distancing and washing and sanitizing hands as a precaution for the general public to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Hospitals should adopt measures to continue medical care and prevent the spread of infection between patients and their medical staff.21

However, some differences exist between societies regarding the cessation of immunomodulators and/or biologics in patients with IBD, regardless of whether they were infected with SARS-CoV-2 or not. The primary recommendations of several IBD societies for dealing with patients with IBD are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Initial Recommendations by Different Societies for IBD Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| IBD Patients | IBD Patients Not Infected With SARS-CoV-2 | IBD Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention | In Remission | In Flare | Without COVID-19 Symptoms | With COVID-19 Symptoms | |

| China15 | - Continue treatment with caution. - A new prescription or increase in dose of an immunosuppressant is not recommended. Enteral nutrition might be used if biologics are not available. |

- Contact IBD doctor for suitable medicine. | - Screen for COVID-19 with serology and imaging before emergency surgery. | - Contact IBD doctor if temperature rises above 38°C. - Suspend immunosuppressants and biologics after consultation with IBD doctor. |

|

| Italy16 | - Low dose and short-term steroids are safe. - Thiopurines and JAK inhibitors: do not stop in patients following prevention strictly. Delay the start of new therapies. |

- Steroids can be used in case of need. | - Low-dose and short-term steroids are probably safe in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. | ||

| AGA17 | - Continue IBD therapies. - Continue infusion at appropriate centers. |

- Lower doses of prednisone (< 20mgmg/d) or transition to budesonide. - Halt thiopurines, methotrexate and tofacitinib temporarily. - Dosing of biologics should be delayed for 2 weeks while monitoring for symptoms. |

- Hold thiopurines, methotrexate, tofacitinib, and biologics during illness. - Restart after Complete resolution or, when follow-up viral testing is negative, or serology indicates convalescence. - Careful risk assessments for treatments of COVID-19. - Limit IV steroids to 3 days, at which point the decision to proceed with a calcineurin inhibitor or infliximab will be made in patients with active IBD. - Consider testing for CMV activation. |

||

| IOIBD14 (The International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases) |

- Reduce the dose or stop prednisone.- In case of an immune modulator with a biologic, dose may be reduced. | - Continue to receive infusions in an infusion center. | - Discontinue immune modulators. - Restart medications if patients do not show symptoms after 2 weeks. |

- Discontinue immune modulators. - Restart medications if symptoms have completely resolved or after 2 nasopharyngeal PCR tests are negative. |

|

| ECCO22 (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization) |

- Immunosuppressive and biological drugs should not be discontinued as a preventive strategy. - Discourage all nonessential travel and recommend protective aids. - Nonurgent outpatient visits should be postponed. |

- The start of new biological drugs should be allowed if adequate protective measures can be guaranteed. | - The SARS-CoV-2 test should not be performed in IBD patients without symptoms. |

OUR IBD UNIT

Our IBD unit in the Tropical Medicine Department, Ain Shams University Hospitals, Cairo, Egypt, which is one of the largest tertiary hospitals in Egypt, started its work in 2011.We follow approximately 200 patients with IBD per year from all over Egypt (rural and urban areas). Our unit offers all types of services for patients with IBD, beginning with diagnostic evaluation and all types of treatment, including some types of biological treatment in our infusion center, and follow-up of our patients.

Regarding our patients with IBD, 80.5% presented with UC, and 19.5% presented with CD. Most of the UC cases presented to our department as moderate disease (55.9%), according to the criteria of Trulove and Witts, whereas most of the CD cases presented to us as moderate to severe disease (66.7%), according to the CD Activity Index. Approximately 73% of our patients are maintained on azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg), and 19% of our patients with IBD are controlled on biological therapy (either infleximab or adalimumab).

Since the COVID-19 outbreak started, our hospital was involved in the management of patients with COVID-19, requiring many clinicians to be reassigned to manage COVID-19-infected inpatients.

Our patients with IBD were significantly worried regarding whether they were at a higher risk of contracting the COVID-19 infection, the effect of their IBD medications on the course of infection, and the expected prognosis. Fortunately, since the start of the outbreak up through the writing of this manuscript, only 2 patients with IBD in our department tested positive for COVID-19 infection.

At first, we began to phone our patients and send them regular messages to strictly follow the general recommendations of the World Health Organization for protection against COVID-19.23 These recommendations included the following:

Regularly and thoroughly clean hands with an alcohol-based hand rub or wash them with soap and water.

Clean surfaces with an alcohol-based sanitizer where infected droplets may lie.

Maintain at least 1 m (3 feet) distance from anyone who is coughing or sneezing.

Avoid touching eyes, nose, and mouth. A mask may help in preventing this.

One should stay at home if one feels unwell.

Wear a mask to protect yourself as well as to avoid infecting other people, even in case of mild symptoms and in any case in which the recommended distance cannot be kept.

Wear gloves when going shopping and all other outside activities to minimize the risk of hand contamination.

Avoid using public toilets as much as possible, as the toilet bowl, sink, and door handle can be contaminated.

By the middle of March 2020, all of our noncritically ill and stable patients with IBD were discharged from our unit with strict follow-up.

HOW DID THE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN PATIENTS AND IBD DOCTORS TAKE PLACE IN OUR UNIT?

Communication was managed through direct phone connection (calls and messages via What’s App). Patients in our IBD unit were provided with the official phone contact of the group for emergency situations and laboratory feeds at any time, saved by the patient’s name and his group ID number. Regular circulars are also sent to all patients, which include epidemic health precautions, warning signs, reminders for follow-up dates, and new treatment prescriptions (electronic prescriptions) or required labs.

In addition, a live weekly IBD team meeting was conducted through the Zoom app. The weekly meeting was held for all group members to discuss newly diagnosed cases and follow-up on existing patients to adjust treatment when indicated. A multidisciplinary approach in management is always guaranteed with the team, comprising members from colorectal surgery, pathology, radiology, and nutrition staff.

THE STRATEGY FOR MANAGING IBD PATIENTS IN OUR UNIT DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Patients in Stable Remission

Following general precautions was more important than ever. Patients were instructed to inform us immediately if they experienced any suspicious symptoms (fever, cough, sore throat) or exacerbation of their symptoms. Routine follow-up visits and endoscopies were postponed, and follow-up was conducted by phone.

We recommend continuing the same treatment for patients with IBD, including 5-ASA, azathioprine, and biological therapy, to avoid relapse, which might require an emergency room visit, hospitalization, or steroid induction. All of these could consequently increase a patient’s risk of contracting COVID-19 infection. Weekly follow-up and decision-making were replaced by online meetings to avoid face-to-face contact.

In Case of IBD Flare

When patients reported exacerbations of their symptoms, urgent laboratory investigations (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein) were requested to classify the degree of the disease (mild, moderate, or severe) according to the criteria of Trulove and Witts for UC and the Clinical Disease Activity Index for CD.

Then, patients were managed accordingly. In mild cases, we only adjusted the treatment regimens at home. In moderate cases, we applied an oral short course of steroid therapy along with oral ciprofloxacin (500 mg/12 h for 5 d) and oral metronidazole (500 mg/8 h for 5 d) with strict follow-up of the clinical situation by our IBD specialists through What’s App. In severe cases, we considered an urgent IBD clinic visit for the patient, with the possibility of admission.

The following steps illustrate a patient’s pathway upon entering our hospital:

-

•

In the triage emergency room, the patient was thoroughly asked about the history of contact with anyone with COVID-19, recent travel to endemic areas, respiratory symptoms, fever, or recent loss of taste or smell. If any of these were positive, the patient was transferred directly to a triage section where labs (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, ferritin, D dimer), chest computed tomography, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for COVID-19 were performed.

-

•

Patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were transferred directly to a special building within the hospital’s campus dedicated to isolating COVID-19-positive patients. To plan for an increase in cases, university authorities dedicated the university hospital in Alobour city as a back-up hospital for COVID-19 isolation, making this the largest isolation university hospital in Egypt.

-

•

Patients who tested negative for COVID-19 were admitted to the regular ward rooms following specific regulations established by the infection control unit, which include placing a single patient per room, use of full personal protective equipment (PPE) for doctors and nurses, no visitors allowed for the patients, and a daily evaluation to detect any suspicious symptoms of COVID-19.

-

•

If a patient presented with gastrointestinal flare alone (eg, diarrhea) with no other symptoms suspicious for COVID-19, that patient moved through the triage without COVID-19 testing unless any suspicious labs or symptoms developed. However, this differential diagnosis was kept in mind while managing patients presenting with flare in the ward (activity vs early COVID-19) with close follow-up.

All IBD staff was obliged to wear all PPE during contact with patients. From the beginning, our surgical team was engaged in follow-up and decision-making. Urgent lab investigations were performed to exclude causes of activity (Clostridium difficile invasion or other pathogens), along with blood and stool culture and sensitivity. Short unprepared sigmoidoscopy was also sometimes considered for newly diagnosed cases or to rule out cytomegalovirus infection after applying full PPE for our endoscopy staff. Cross-sectional abdominal imaging (pelviabdominal computed tomography) was also sometimes considered to exclude collections, fistulae, or abscesses.

We considered starting short-term intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg/6 h) along with appropriate antibiotics according to the culture and sensitivity. Thiopurines and methotrexate were avoided at this time. We considered early use of biological therapy for severe cases if they did not respond to intravenous hydrocortisone within 5 days.

The biological therapies available in our unit are infleximab, adalimumab, and golimumab. Vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and tofacitinib are not available in our unit. We preferred to start with adalimumab for newly diagnosed cases to avoid the need for inpatient infusion.

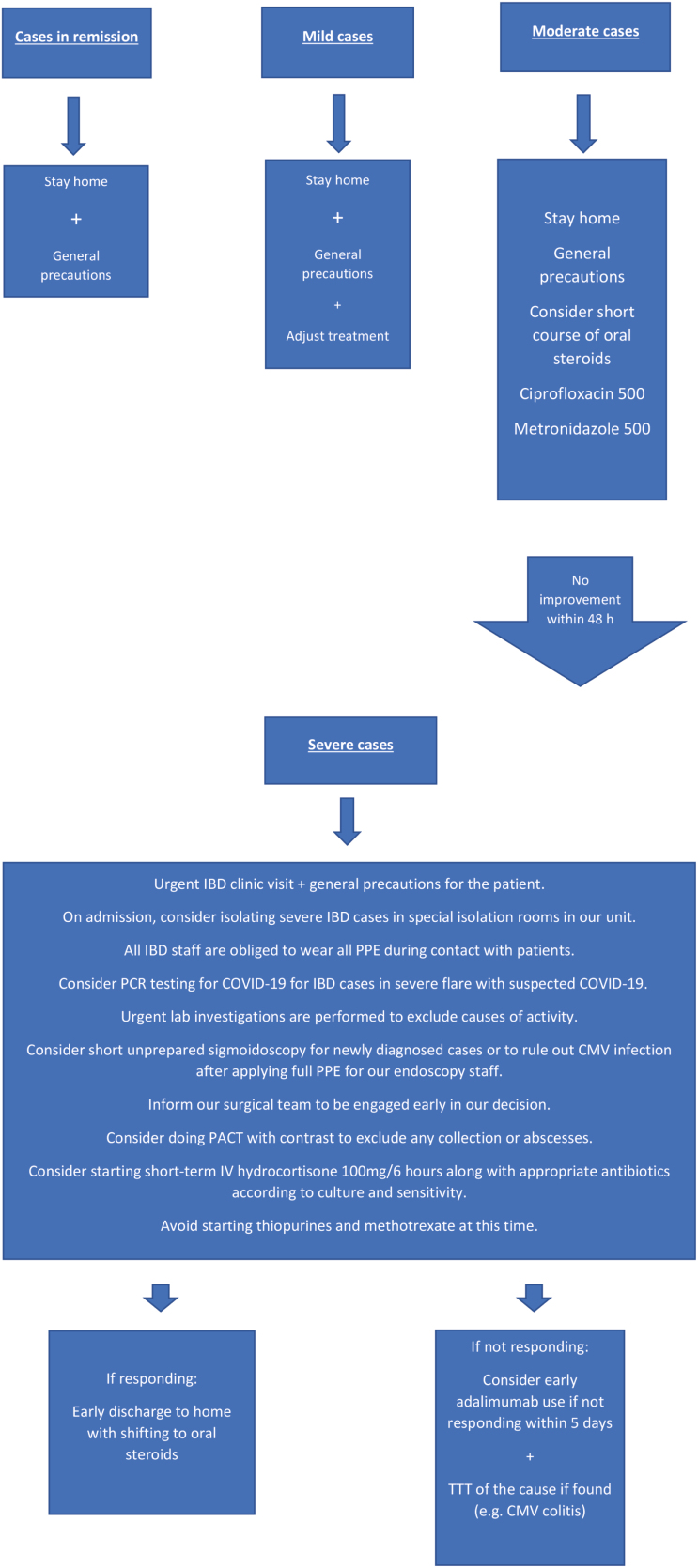

If the patient demonstrates improvement, we considered early home discharge with strict follow-up with our IBD specialists through direct phone connection using the IBD unit’s official phone number, which allows the receipt of follow-up feeds regarding the patient’s general condition, new labs, inquiries, and emergency calls if necessary. Each of these feeds is discussed weekly during our IBD team meeting through the Zoom app (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart showing the management of IBD cases according to disease severity.

CASE SERIES

In total, 11 patients with IBD presented to our unit in April and May 2020. Of these, 7 patients presented with UC, and the remaining 4 presented with CD. Of the 4 patients with CD, 1 was stable on adalimumab, whereas the 3 others presented with fistulizing CD (management will be discussed later) and were admitted at our unit at Ain Shams University Hospitals. All patients with CD presented with the ileocecal phenotype of the disease. Of the 7 patients with UC, 3 were on maintenance biological therapy (adalimumab or infliximab), 2 were started on a loading dose of biologics due to severe UC, and 2 presented with fever and respiratory symptoms suspicious of COVID-19. These 2 patients were subsequently tested, and the result was positive, so they were admitted to an isolation hospital. From the beginning of the outbreak in Egypt until the writing of this manuscript in May 2020, these 2 patients were the only IBD patients in our department with confirmed COVID-19 infection (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Cases Presented to our IBD Unit in April and May 2020

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of IBD | CD | CD | CD | CD | Left-sided UC |

| Sex | F | M | M | M | M |

| Medical therapy | Adalimumab (maintenance) | 5-ASA, prednisolone, and azathioprine | Adalimumab (maintenance) | Infliximab (maintenance) | 5-ASA, prednisolone, and azathioprine |

| History of bowel surgery | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| C/P | Symptom free | Abdominal pain and purulent discharge | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and purulent discharge | Abdominal pain and purulent discharge | Bloody diarrhea (steroid resistant UC) |

| Cause of presentation | Maintenance dose of adalimumab | Fistulizing CD Right iliac fossa abscess |

Fistulizing CD Left iliac fossa abscess |

Fistulizing CD Right iliac fossa collection |

Loading dose of adalimumab |

| Hospitalization | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | Cases 10 and 11 | |

| Type of IBD | Extensive UC | Extensive UC | Extensive UC | UC (pancolitis) | Left sided UC (10) ulcerative proctitis (11) |

| Sex | F | F | F | F | F |

| Medical therapy | 5-ASA, prednisolone, and azathioprine | Adalimumab (maintenance) | Adalimumab (maintenance) | 5-ASA and azathioprine | 5-ASA |

| History of bowel surgery | No | No | No | No | No |

| C/P | Bleeding per rectum and abdominal pain (steroid-dependent UC) | Mild abdominal pain | Symptom free | Bleeding per rectum (dependent UC) | Fever with dry cough No GIT related symptoms |

| Cause of presentation | Loading dose of infliximab | Maintenance dose of adalimumab | Maintenance dose of adalimumab | Loading dose of infliximab | Suspicion of IBD activity. Exclusion of COVID-19 infection (swab result was positive) |

| Hospitalization | No | No | No | No | The patients were admitted to an isolation hospital) |

Case 1

The first case positive for COVID-19 was a 40-year-old woman diagnosed with left-sided UC 2 years ago after developing attacks of chronic diarrhea of 6 months’ duration. She was in remission on oral 5-ASA (3 g/d). Unforunately, in the begining of April 2020, she developed a fever (high grade, constant through the day) with a dry cough and generalized fatigue, without any response to ordinary management. She presented with no history of close contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19 or recent history of traveling outside Egypt. She contacted our team by phone. The patient was asked to present to our emergency room, where she was triaged. Laboratory tests were ordered, which revealed marked lymphopenia, high ferritin level, and D dimer. High resolution chest computed tomography revealed peripheral ground glass apperance in both lung lobes. Polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 was positive. She was admitted to our isolation hospital. Personnel in the emergency room and triage system were protected with full PPE, nessiciating no isolation actions. The patient’s family was informed by a member of our IBD unit and given adequate isolation instructions and warning symptoms to report.

The patient received hydroxychlorochine (400 mg) twice as a loading dose on day 0, then 200 mg twice per day plus oseltamivir (75 mg) twice daily, along with low molecular weight heparin (prophylactic dose) and azithromycin (250 mg) twice per day with continuation of 5-ASA (3 g/d). She did not develop any gastrointestinal tract symptoms during this period. In the next few days after admission, her fever subsided, and her cough improved. Two successive negative PCR tests for COVID-19 were obtained on day 10 and 12. The patient was dischaged in very good condition with continued home isolation for 2 weeks.

Case 2

The second case positive for COVID-19 was a 36-year-old woman diagnosed with ulcerative proctitis 3 years ago. She was controlled on oral 5-ASA (3 g/d), along with a mesalamine supposatory (1000 mg) once per day. She developed a high-grade fever along with dry cough in mid-April 2020. The patient was instructed to present to our emergency room, where she was triaged. Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and D dimer tests were ordered. The results were compatible with COVID-19. Polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 was requested, and the result was positive. She was admitted to our isolation hospital and received the same protocol of treatment as described for Case 1, with continuation of her UC treatment. She improved with 2 successive negative PCR tests on days 7 and 9 and was then discharged to home.

MANAGEMENT OF 3 CASES WITH FISTULIZING ILEOCECAL CD HOSPITALIZED DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Case 3

Case 3 was a 32-year-old man with newly diagnosed ileocecal CD by biopsy. He was on prednisolone (40 mg) with gradual tapering and azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg). He developed a new onset of fever, abdominal pain, and purulent discharge at the right iliac fossa with no pulmonary symptoms. The patient was instructed to present to our emergency room, where he was triaged. After the exclusion of COVID-19 infection as mentioned previously, new pelvic abdominal computed tomography revealed active ileocecal penetrating CD complicated by abscess formation tracking to the abdominal wall and subsequent enterocutaneous fistula formation.

The surgical team in our unit recommended conservative treatment. We began empirical antibiotics and metronidazole. Intravenous hydrocortisone (100 mg/6 h) was started shortly after antibiotics. Over the next few days, the patient’s fever began to subside, and a decreasing amount of purulent discharge occurred. The patient did not require draining of the abscess transcutaneously.

After 10 days of conservative treatment, the collection was significantly drained. After discussion with our team and surgeons, we decided to prepare the patient for adalimumab. The patient started induction (160 mg) of adalimumab with gradual tapering of prednisolone (5 mg/week). The patient was discharged with strict follow-up with our team as described previously.

Case 4

Case 4 was a 38-year-old man with ileocecal CD maintained on adalimumab (40 mg/2 weeks). In mid-April 2020, the patient reported purulent discharge from the left iliac fossa. The patient was instructed to present to our emergency room, where he was triaged for exclusion of COVID-19 according to our hospital policy. Then the patient was admitted to our unit. Pelvic-abdominal computed tomography revealed multiple colonic wall mural thickening with fistula formation to the left anterior abdominal wall muscles forming encysted infected collection (abcsess) measuring approximately 5.9 cm × 2 cm with no other fistulous communications. After discussion with our surgeons, the patient underwent localized surgical drainage for the abscess. The patient was kept on strong antibiotics, on which he showed a good response with resuming of his scheduled dose of adalimumab. The length of hospitalization for this patient was 10 days including the surgical procedure.

Case 5

Case 5 was a 42-year-old man with iliocecal CD. He was maintained on infleximab (5 mg/kg/8 wk), along with azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg) beginning 1 year ago. The last dose of infleximab was given in December 2019. Due to administrative problems with his insurance approval at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in Egypt, the patient skipped his next dose of infleximab. In mid-April 2020, he presented to our unit with abdominal pain and right iliac fossa fistula formation. He was admitted to our unit after passing our hospital triage system for exclusion of COVID-19. Photoacoustic computed tomography revealed a right iliac fossa small abscess with small enterocutaneous fistulous track formation. The patient was managed conservatively with no radiological or surgical interference. He was kept on his regular biological therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 pandemic is still a major health problem worldwide, impacting every person, health care worker, and patient. Patients with IBD should follow the general recommendations and precautions for protection against COVID-19 infections. In general, patients with IBD should continue their therapies with strict follow-up with the IBD team through safer contact channels (ie, phone, online). Patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection should contact their IBD team for proper management of their therapies and immunomodulators.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article. No funding was received for this work from any organization.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. . Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. . A novel Coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. World Health Organization (WWW.WHO.INT), 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egypt cares. https://www.care.gov.eg/EgyptCare/Index.aspx. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 6. An P, Ji M, Ren H, et al. . Protection of 318 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients from the Outbreak and Rapid Spread of COVID-19 Infection in Wuhan, China https://ssrn.com/abstract=3543590. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 7. El-Bassyouni H, Elatrebi K. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) unit: an Egyptian experience. ECGDS. 2017;5.1:01. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mostafa EF, Metwally A, Hussein SA. Inflammatory bowel diseases prevalence in patients underwent colonoscopy in Zagazig University Hospitals. AEJI. 2018;8:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, et al. . Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esmat S, El Nady M, Elfekki M, et al. . Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of inflammatory bowel diseases in Cairo, Egypt. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:814–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. . A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. . Evidence for Gastrointestinal Infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. . Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rubin DT, Abreu MT, Rai V, et al. ; International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of an international meeting. Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mao R, Liang J, Shen J, et al. . Implications of COVID-19 for patients with pre-existing digestive diseases. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:426–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiorino G, Allocca M, Furfaro F, et al. . Inflammatory bowel disease care in the COVID-19 pandemic era: the Humanitas, Milan experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2020. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubin DT, Feuerstein JD, Wang AY, et al. . AGA clinical practice update on management of inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: expert commentary. Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farrell RJ, Murphy A, Long A, et al. . High multidrug resistance (P-glycoprotein 170) expression in inflammatory bowel disease patients who fail medical therapy. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pithadia AB, Jain S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glocker E, Grimbacher B. Inflammatory bowel disease: is it a primary immunodeficiency? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Danese S, Cecconi M, Spinelli A. Management of IBD during the COVID-19 outbreak: resetting clinical priorities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:253–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D’Amico F, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L; on behalf of the ECCO COVID taskforce . Inflammatory bowel disease management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a survey from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO). Gastroenterology. 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization. Q&A on Coronaviruses [COVID-19] 2020. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses.