Abstract

Background

The mortality effects of COVID-19 are a critical aspect of the disease’s impact. Years of life lost (YLLs) can provide greater insight than the number of deaths by conveying the shortfall in life expectancy and thus the age profile of the decedents.

Methods

We employed data regarding COVID-19 deaths in the USA by jurisdiction, gender and age group for the period 1 February 2020 through 11 July 2020. We used actuarial life expectancy tables by gender and age to estimate YLLs.

Results

We estimated roughly 1.2 million YLLs due to COVID-19 deaths. The YLLs for the top six jurisdictions exceeded those for the remaining 43. On a per-capita basis, female YLLs were generally higher than male YLLs throughout the country.

Conclusions

Our estimates offer new insight into the effects of COVID-19. Our findings of heterogenous rates of YLLs by geography and gender highlight variation in the magnitude of the pandemic’s effects that may inform effective policy responses.

Keywords: COVID-19, years of lost life, mortality

Introduction

Mortality is a primary means to measure the impact of COVID-19. Information regarding the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 can help policy makers and health care providers to understand the extent of the outbreak. Mortality comparisons can provide insight into the impact of the disease across geographic areas and sociodemographic variables. Mortality measures can also be crucial in understanding past and future trends of the pandemic.

Measuring COVID-19 deaths has been difficult due to evolving diagnosis criteria,1 testing supply constraints2 and the ‘fog of war’ in over-burdened intensive care units.3 However, even if correctly measured, the number of deaths is an imperfect measure of mortality as it does not provide insight into the age distribution of deaths or how risk levels vary by age. Therefore, the number of deaths cannot offer sufficient information as to how much many years of life was lost due to the disease.

In contrast, years of life lost (YLLs) are based on both the number of deaths and the age of those who died. YLLs estimate the number of years that those who died would have lived if they did not contract the specified condition. Higher YLLs can be due to larger numbers of death, younger decedents or some combination of the two. If the necessary data are available, YLLs are a flexible measure which have been used to measure the effects of overall mortality,4 non-communicable diseases,5–8 drug misuse9,10 and suicide,11,12 among other areas.

The relatively older profile of COVID-19 decedents13 would suggest that YLLs due to COVID-19 would be relatively low. However, there have been a considerable number of deaths of younger individuals. The variation in how COVID-19 has affected different areas may have caused subsequent variation in YLL estimates across areas. There are few existing studies of COVID-19 that have employed YLLs. Per-capita YLLs in the USA were roughly 13% greater than those in Italy and more than six times as large as those in Germany.14 The combined YLLs of African Americans and Latinos are more than that of whites, despite the population of whites being significantly larger.15 A model was developed for the UK that based the estimates of YLLs on the observed morbidities of those who died of COVID-19 in Italy.16 Based on this adjustment, the modeled YLLs per COVID-19 death were 13 for men and 11 for women.

The goal of this study was to investigate the relationship between the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 and the associated YLLs in the USA for the period 1 February 2020 through 11 July 2020. YLLs were compared across jurisdictions and genders.

Methods

Data

Information regarding COVID-19 deaths was obtained from the dataset ‘Provisional COVID-19 Death Counts by Sex, Age, and State’ published by the National Center for Health Statistics in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).17 Below we use the term jurisdiction rather than state to refer the geographic entities as the CDC data included observations for the non-state areas New York City, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. The data employed in the analysis were as of 22 July 2020. For confidentiality reasons, the number of deaths was suppressed in the dataset for a given jurisdiction/gender/age group if the value ranged from one to nine. Out of 60 570 female deaths, 429 did not include information regarding age. The corresponding values for male deaths were 69 675 and 420. For each jurisdiction-gender that had an age group with suppressed deaths, we applied the national proportions of deaths by age group for each gender to the number of suppressed deaths. There were five deaths for which the gender was unknown and which were excluded from the analysis.

Life expectancies by age and gender were obtained from actuarial life tables published by the US Social Security Administration.18 The most recent year available was 2017. Appendix Table 1 reports the mapping of age groups used in the COVID-19 deaths data to ages for which the life expectancy was used.

‘Annual State Resident Population Estimates’ published by the US Census Bureau was the source of our state-level population data.19 The data were as of 1 July 2019 and were obtained by gender. Following the COVID-19 deaths data, we estimated the population of New York City and the remainder of New York state separately. We obtained the population of New York City and the percentage of population by gender as of 1 July 2019 from ‘QuickFacts: New York City, New York’ published by the US Census Bureau.20

Our initial sample consisted of 49 states, New York state excluding New York City, New York City, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico. Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Wyoming were excluded from the analysis as they did not report deaths by gender.

Statistical analysis

We approximated the age of death for each age group based on the single-age values reported in Appendix Table 1. For each death, we calculated the approximated age of death from the life expectancy for that gender-age cohort. We obtained population-level YLL estimates by summing these differences for the deaths in the relevant population. Per-capita YLLs were calculated per 10 000 residents for the respective jurisdiction-gender population.

A significant aspect of COVID-19 deaths in calculating YLLs is that many of those who died of the disease had significant pre-existing medical conditions. Such deaths could be considered as displaced mortality in that these individuals on average would likely not reach the full life expectancy reported in actuarial tables. In their forecast model of COVID-19 deaths in the UK based on data from Italy, Hanlon et al. (2020) estimated that the greater pre-existing morbidity of those who died of COVID-19 reduced the estimated YLLs per COVID-19 death from 14 to 13 for men and 12 to 11 for women.15 In our analysis, we conservatively reduced the expected life expectancy by 25% to reflect the typically greater morbidity of COVID-19 decedents.

Results

Table 1 reports by jurisdiction the number of deaths and YLLs for each jurisdiction included in the sample. The top row shows that the US total and the jurisdictions are sorted in descending order of YLLs. During our sample period, there were roughly 130 000 deaths which translated to approximately 1.2 million YLLs. New York City alone accounted for roughly one-sixth of the deaths and YLLs. The top 10 jurisdictions represented roughly three-quarters of all YLLs. As expected, the rankings of jurisdictions by the number of deaths and YLLs are similar, with Massachusetts, an exception among the top 10 (fourth in the number of deaths and seventh in YLLs).

Table 1.

Number of deaths and YLLs by jurisdiction

| Jurisdiction | Number of deaths | YLLs |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 130 088 | 1 215 265 |

| New York City | 20 457 | 217 599 |

| New Jersey | 13 809 | 128 887 |

| New York (excl NYC) | 11 242 | 100 200 |

| California | 7100 | 70 972 |

| Illinois | 6649 | 65 382 |

| Pennsylvania | 7226 | 56 719 |

| Massachusetts | 7752 | 54 890 |

| Michigan | 5594 | 54 036 |

| Texas | 3703 | 42 033 |

| Florida | 4340 | 39 188 |

| Maryland | 3621 | 34 325 |

| Louisiana | 3088 | 31 023 |

| Connecticut | 4028 | 30 103 |

| Arizona | 2441 | 26 137 |

| Georgia | 2545 | 25 779 |

| Indiana | 2731 | 22 900 |

| Ohio | 2700 | 22 280 |

| Virginia | 2067 | 17 883 |

| Colorado | 1640 | 13 951 |

| Alabama | 1264 | 13 218 |

| Mississippi | 1204 | 13 035 |

| North Carolina | 1220 | 11 366 |

| Minnesota | 1482 | 10 936 |

| Washington | 1234 | 10 574 |

| South Carolina | 965 | 9471 |

| Missouri | 1013 | 8438 |

| Wisconsin | 823 | 7868 |

| District of Columbia | 642 | 7371 |

| Iowa | 790 | 7268 |

| Tennessee | 670 | 7024 |

| Rhode Island | 935 | 6769 |

| Nevada | 575 | 6212 |

| New Mexico | 515 | 5843 |

| Kentucky | 655 | 5653 |

| Delaware | 513 | 4499 |

| Oklahoma | 417 | 3794 |

| Arkansas | 359 | 3755 |

| Nebraska | 283 | 2924 |

| Kansas | 312 | 2906 |

| New Hampshire | 380 | 2539 |

| Utah | 216 | 2329 |

| Oregon | 255 | 2255 |

| South Dakota | 112 | 1016 |

| Maine | 127 | 938 |

| North Dakota | 102 | 823 |

| Idaho | 114 | 803 |

| West Virginia | 101 | 773 |

| Vermont | 52 | 388 |

| Montana | 25 | 190 |

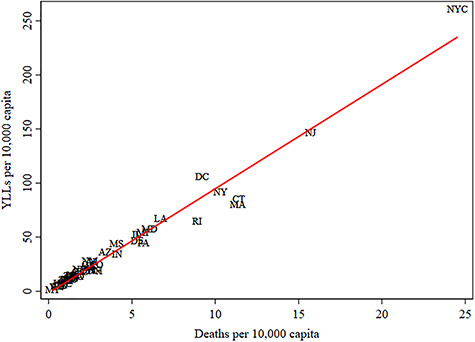

The scatterplot in Fig. 1 shows the number of deaths and YLLs per capita. Jurisdictions above the trend line had higher rates of YLLs to deaths relative to average, while the reverse was true for jurisdictions below the trend line. The vast majority of jurisdictions lie on or very near the trend line. New York City is the greatest departure from the trend line and had a relatively younger age profile of COVID-19 deaths, as did Washington, D.C. In contrast, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island were considerably below the line.

Fig. 1.

YLLs and deaths per 10 000 capita.

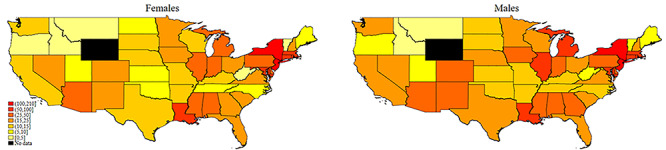

Figure 2 contains maps of YLLs per capita by gender, where the darker shading reflects higher YLLs per capita. New York excluding New York City, and New York City are combined in the maps. The highest YLLs per capita are generally located in the northeast, with Louisiana as the one jurisdiction outside the region with the darkest shade in both maps. All of the jurisdictions on the map for males are as darkly or more darkly shaded than the corresponding jurisdictions on the females map. The jurisdictions in the northeast generally have the same shading for both genders.

Fig. 2.

YLLs per 10 000 capita by gender.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the robustness of our estimates. Appendix Table 2 reports our findings when we assumed that the life expectancy of COVID-19 decedents was 50% less (rather than 25% less) of average. While the values were obviously less, the total YLLs was over 800 000.

Discussion

The main findings

The goal of this study was to use YLLs to gain insight into the mortality effects of COVID-19 in the USA. We found that from 1 February 2020 through 11 July 2020, COVID-19 was responsible for roughly 1.2 million YLLs. We observed a rough congruence of jurisdiction rankings in the number of deaths and YLLs. The two cities in our sample (New York City and Washington, D.C.) had younger age profiles of COVID-19 decedents than the national average. Jurisdiction maps by gender revealed that throughout the USA, the YLLs per capita for males were at least as large and often larger than those for females.

What is already known on this topic

Despite its importance, there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of COVID-19 mortality. As noted above, there are significant impediments that can prevent the correct identification of COVID-19 deaths. The data are further muddled by difference across jurisdictions in how COVID-19 deaths are identified. Some jurisdictions rely on reports to local health officials, while others use information recorded on death certificates. Excess mortality analyses can potentially provide more accurate counts of COVID-19 deaths.21–23 However, these studies typically have limited ability to associate demographic characteristics with deaths.

While imperfect, the data on reported COVID-19 deaths suggest several seemingly established patterns. For instance, the data employed in this study suggest extensive variation in deaths across states. Table 1 showed that the northeast region of the USA had especially large numbers of deaths, but other jurisdictions had relatively few. In five jurisdictions, there were over 10 deaths per 10 000 capita, while in eight jurisdictions, there were fewer than one death per 10 000 capita. COVID-19 deaths are largely centered on older individuals, with nearly 80% of deaths nationwide occurring among those aged 65 or greater.13 Deaths occurred more frequently among males at roughly 55% of all deaths,13 which may reflect increased rates among males of certain pre-existing medical conditions and/or differences in pre-COVID-19 management of heath conditions.24

What this study adds

While data on the number of COVID-19 deaths are informative, YLLs can add critical texture to our understanding. However, to date, the use of YLLs to measure the effects of COVID-19 has been very limited. While the existing studies on overall YLLs,13 racial and ethnic disparities,14 and models to predict YLLs15 provide important insight, there are additional important aspects that have not been investigated.

Our analysis provides critical new insight into COVID-19 deaths by employing YLLs to identify the varying effects of COVID-19 across jurisdictions, genders and age groups. We found that deaths in New York City were responsible for roughly one-sixth of the YLLs in the USA. Furthermore, the sum of the YLLs in the top six jurisdictions was greater than the sum of the remaining 43 jurisdictions. Our comparisons of YLLs and deaths per capita indicated significant variation in the distribution of ages across jurisdictions. For instance, New York City and Washington, D.C. had per-capita YLLs that were above the national trend line. A potential explanation for this finding is that New York City and Washington, D.C. are both cities and their younger age profile reflects the age of residents and population density in cities.

We improved upon existing studies by using actuarily based life expectancy estimates by age group rather than using somewhat arbitrary cut-off ages. We attempted to account for the typically worse pre-existing health status of COVID-19 decedents by discounting life expectancy in our calculations. Our jurisdiction-level analysis was especially appropriate given the extensive variation across states in the number of deaths and outbreak phases of COVID-19. Our jurisdiction-level maps by gender demonstrate that throughout the country, generally male deaths have led to greater YLLs than female deaths.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. We were unable to investigate jurisdiction-level racial and ethnic disparities due to data availability. We employed national life expectancy estimates as jurisdiction-level data were not available. As noted above, the COVID-19 deaths data were provisional and thus incomplete. The reporting delays can range from 1 to 8 weeks and vary by jurisdiction. An implication of these delays was that it was not feasible to analyze YLLs over time due to delays.

We had to employ a rough approximation for the pre-existing reduced expected life expectancy of those who died from COVID-19. While our use of a 25% reduction is conservative, especially in light of earlier estimates,15 a more precise estimate based on US data would provide greater clarity.

Conclusions

This study of the roughly first 5 months of the COVID-19 epidemic in the USA calculated the YLLs by jurisdiction and gender. Our national estimates of 1.2 million YYLs due to COVID-19 deaths provide important context to the effects of the disease. Our findings of differential effects by jurisdiction and gender indicate important heterogeneities in the mortality effects of COVID-19. It will be vital to continue to monitor YLLs due to COVID-19 to inform policy and clinical responses to the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Troy Quast, Professor

Ross Andel, Professor

Sean Gregory, Associate Professor

Eric A. Storch, Professor

Contributor Information

Troy Quast, University of South Florida, College of Public Health, Tampa, FL 33612, USA.

Ross Andel, University of South Florida, College of Behavioral and Community Sciences, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; Department of Neurology, Charles University and Motol University Hospital, Prague, 150 06, Czechia; International Clinical Research Center, St. Anne’s University Hospital, Brno, 656 91, Czechia.

Sean Gregory, Department of Politics and International Affairs, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA.

Eric A Storch, Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

References

- 1. Council of State & Territorial Epidemiologists Position Statement: Standardized surveillance case definition and national notification for 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/2020ps/Interim-20-ID-01_COVID-19.pdf(5 April 2020, date last accessed).

- 2. Resnick B, Scott D. America’s shamefully slow coronavirus testing threatens all of us. Vox; https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/3/12/21175034/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-usa(12 March 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goh KJ, Wong J, J-CC T et al. Preparing your intensive care unit for the COVID-19 pandemic: practical considerations and strategies. Crit Care 2020;24:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vienonen MA, Jousilahti PJ, Mackiewicz K et al. Preventable premature deaths (PYLL) in northern dimension partnership countries 2003–13. Eur J Public Health 2019;29(4):626–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Kush SJ et al. Life expectancy and years of life lost in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: findings from the NHANES III follow-up study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:137–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martinez R, Soliz P, Caixeta R et al. Reflection on modern methods: years of life lost due to premature mortality—a versatile and comprehensive measure for monitoring non-communicable disease mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48(4):1367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de VE, Meneses MX, Piñeros M. Years of life lost as a measure of cancer burden in Colombia, 1997-2012. Biomedica 2016;36(4):547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alva ML, Hoerger TJ, Zhang P, Cheng YJ. State-level diabetes-attributable mortality and years of life lost in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28(11):790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Imtiaz S, Shield KD, Roerecke M et al. The burden of disease attributable to cannabis use in Canada in 2012. Addiction 2016;111(4):653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salazar A, Moreno S, Sola HD et al. The evolution of opioid-related mortality and potential years of life lost in Spain from 2008 to 2017: differences between Spain and the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2020;36(2):285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jung Y-S, Kim K-B, Yoon S-J. Factors associated with regional years of life lost (YLLs) due to suicide in South Korea. IJERPH 2020;17(14):4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Izadi N, Mirtorabi SD, Najafi F et al. Trend of years of life lost due to suicide in Iran (2006–2015). Int J Public Health 2018;63(8):993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wortham JM, Lee JT, Althomous S et al. Characteristics of persons who died with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(28):923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitra AK, Payton M, Kabir N et al. Potential years of life lost due to COVID-19 in the United States, Italy, and Germany: an old formula with newer ideas. IJERPH 2020;17(12):4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basset M, Chen J, Krieger N. The unequal toll of COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: Quantifying racial/ethnic disparities. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1266/2020/06/20Bassett-Chen-Krieger_COVID-19_plus_age_working-paper_0612_Vol-19_No-3_with-cover.pdf (20 June 2020, date last accessed).

- 16. Hanlon P, Chadwick F, Shah A et al. COVID-19 – exploring the implications of long-term condition type and extent of multimorbidity on years of life lost: a modelling study. Wellcome Open Res 2020;5:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Provisional COVID-19 death counts by sex, age, and state. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Death-Counts-by-Sex-Age-and-S/9bhg-hcku(22 July 2020, date last accessed).

- 18. U.S. Social Security Administration Actuarial Life Table. [undated] https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html

- 19. U.S. Census Bureau State Population by Characteristics: 2010–2019. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-state-detail.html#par_textimage_673542126

- 20. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: New York City, New York. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork

- 21. Weinberger DM, Chen J, Cohen T et al. Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020. JAMA Intern Med. Published online 1 July 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT et al. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March-April 2020. JAMA. Published online 1 July 2020 . doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Excess mortality in men and women in Massachusetts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet 2020;395(10240):1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in health. EMBO Rep 2012;13(7):596–603. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.