Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing allows quantitative determination of disease prevalence, which is especially important in high-risk communities. We performed anonymized convenience sampling of 200 currently asymptomatic residents of Chelsea, the epicenter of COVID-19 illness in Massachusetts, by BioMedomics SARS-CoV-2 combined IgM-IgG point-of-care lateral flow immunoassay. The seroprevalence was 31.5% (17.5% IgM+IgG+, 9.0% IgM+IgG−, and 5.0% IgM−IgG+). Of the 200 participants, 50.5% reported no symptoms in the preceding 4 weeks, of which 24.8% (25/101) were seropositive, and 60% of these were IgM+IgG−. These data are the highest seroprevalence rates observed to date and highlight the significant burden of asymptomatic infection.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, antibodies, serosurveillance, epidemiology, validation, lateral flow assay, immunoassay, seroprevalence, Chelsea Massachusetts

The diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) illness is based on clinical symptoms and detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and serological testing may aid in diagnosis and in estimating disease prevalence. We have validated the BioMedomics SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin M/immunoglobulin G (IgM/IgG) lateral flow immunoassay (LFA) point-of-care (POC) as a laboratory-developed test in a high-complexity laboratory. This assay identifies anti-receptor binding domain IgM and IgG.

Motivated by a clinical observation that COVID-19 inpatients were enriched for residents from the City of Chelsea and public data showing Chelsea had the highest cumulative COVID-19 case rate in Massachusetts (1890 per 100 000 persons; 712 cases) on 14 April 2020 [1], we performed a rapid, pilot, seroprevalence study at a mobile testing site in Chelsea.

METHODS

Patient Enrolment and Study Design

Over 2 consecutive afternoons (14–15 April 2020), at a mobile testing site at Bellingham Square, a central square in the City of Chelsea that abuts a bus commuter junction, we enrolled 200 interested consenting participants who were Chelsea residents, aged ≥18 years, with no current symptoms and no history of a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. We obtained verbal consent for an anonymized questionnaire and serological testing with no return of results. To minimize ascertainment bias, we did not have any prior advertisement for the study and did not actively recruit individuals locally or online. An information poster in English, Spanish, and Portuguese was available at our site (Supplementary Figure 1). Prospective participants were given a surgical mask and directed to a spaced queue to await discussion with a study investigator and given a copy of the information poster. We had substantial interest within minutes of commencing testing and estimate an average queue length of 7 individuals and a <5% drop-out rate. We did not systematically document the refusal/decline frequency nor the fraction of individuals on day 2 who attended through referral as this was not feasible.

Participants were provided advice on precautions, hand sanitizer or soap, and face masks, and were compensated with a USD $5 voucher. The study was performed with approval of the Partners institutional review board (No. 2020P001081) and the city manager.

Questionnaire

The brief COVID-19–focused anonymized questionnaire was available in 3 languages (English, Spanish and Portuguese, Supplementary Figure 2) and administered in the participant’s preferred language by 2 trilingual doctors (M.G.A. and J.A.V.).

Serological Testing

Participants were tested with the BioMedomics SARS-CoV-2 combined IgM/IgG LFA, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations [2]. Twenty microliters of blood were obtained using a fingerstick lancet (BD microtainer lancet) and applied immediately to the device. This was read after 10 minutes by 1 of 2 trained doctors. Positive, weak positive, and negative bands for control, IgM, and IgG were recorded and a photograph obtained. A second reader reviewed the photographs blinded to the field results and agreement calculated, and consensus was reached on discrepant readings. Our inability to return results was reiterated prior to the fingerstick.

To assess LFA cross-reactivity we used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in which purified receptor binding domain proteins from 2 common cold coronaviruses (HKU1 and NL63) and SARS-CoV-2 were coated on ELISA plates. Detailed methods have been presented elsewhere [3].

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and analyzed by R (version 4.0; the R Foundation). Descriptive summary statistics and regression models were used for the overall group and to compare those who were seropositive to those who were seronegative. We adjusted estimates of prevalence for the sensitivity and specificity of the assay per methods described by Larremore et al [4], using an online tool: https://larremorelab.github.io/covid-calculator1.

RESULTS

Over 2 consecutive afternoons totaling approximately 9 hours, we recruited 200 currently asymptomatic Chelsea residents, who had not previously tested positive for COVID-19, to participate in this anonymous study.

Patient Demographics and Symptoms in the Last 4 Weeks

The median age was 46 years (interquartile range [IQR], 27–55) and 40% were female (Table 1). The median number of cohabiting adults was 2 and the median number of cohabiting children was 1. Nearly half, 42.4% (84/198), had to continue to leave home for work during the COVID-19 epidemic and nearly a quarter, 23.6% (47/199), reported a known COVID-19 contact.

Table 1.

Questionnaire Responses According to Serological Results

| Total (n = 200) |

Antibody Positive, IgM+ and/or IgG+ (n = 63) |

Antibody Negative, IgM−IgG− (n = 137) |

Univariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 46 (27–55) | 44 (36–50) | 47 (37–56) | 0.995 (.990–.999) | .024 |

| Sex (n, % Female) | 80 (40.0) | 33 (52.4) | 47 (34.3) | 1.176 (1.033–1.340) | .015 |

| Cohabiting children, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 1.085 (1.033–1.139) | <.001 |

| Cohabiting adults, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–4) | 1.037 (1.000–1.075) | .045 |

| Left home for work during epidemic, n (%)a | 84 (42.4) | 24 (39.3) | 60 (43.8) | 1.044 (.919–1.187) | .508 |

| Known COVID-19 contact, n (%)b | 47 (23.6) | 20 (31.75) | 27 (19.9) | 1.153 (.991–1.342) | .067 |

| Symptoms in last 4 weeks (n, %) | |||||

| None | 101 (51.5) | 25 (39.7) | 76 (55.5) | 0.873 (.768–.992) | .038 |

| Any | 99 (48.5) | 38 (60.3) | 61 (44.5) | 1.146 (1.008–1.303) | .038 |

| Cough | 53 (26.5) | 23 (36.5) | 30 (21.9) | 1.176 (1.017–1.359) | .030 |

| Runny nose | 48 (24.0) | 17 (27.0) | 31 (22.6) | 1.053 (0.905–1.225) | .505 |

| Sore throat | 47 (23.5) | 15 (23.8) | 32 (23.4) | 1.005 (.863–1.171) | .945 |

| Muscle aches | 46 (23.0) | 19 (30.2) | 27 (19.7) | 1.136 (.975–1.323) | .104 |

| Fever | 40 (20.0) | 21 (33.3) | 19 (13.9) | 1.111 (1.300–1.522) | .001 |

| Reduced level of energy | 36 (18.0) | 17 (27.9) | 19 (13.9) | 1.211 (1.026–1.431) | .025 |

| Reduced sense of smell or taste | 26 (13.0) | 18 (28.6) | 8 (5.8) | 1.543 (1.285–1.852) | <.001 |

| Diarrhea | 19 (9.5) | 10 (15.9) | 9 (6.6) | 1.015 (1.263–1.571) | .037 |

| Shortness of breath | 18 (9.0) | 10 (15.9) | 8 (5.8) | 1.303 (1.042–1.628) | .021 |

| Days since symptom onset, median (IQR)a | 11 (5–14) | 14 (8–21) | 8 (3–14) | 1.0141 (1.0006–1.022) | <.001 |

| Thought they may have/have had COVID-19, n (%)c | 33 (16.9) | 14 (23.3) | 19 (14.1) | 1.151 (.968–1.367) | .113 |

P values less than .05 are shown in bold.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IQR, interquartile range.

aThree missing values.

bOne missing value.

cFive invalid answers.

While all reported no current symptoms, 99 (48.5%) participants reported COVID-19–like symptoms in the preceding 4 weeks, occurring a median of 11 (IQR, 5–14) days prior. The most common symptoms reported were cough (26.5%), rhinitis (24.0%), sore throat (23.5%), and myalgia (23.0%) (Table 1); 13.0% reported a reduced sense of smell or taste. Only 16.9% thought they had or have had COVID-19 illness.

SARS-CoV-2 Serology

We validated the Biomedomics LFA assay using blood samples from 57 inpatients admitted for COVID-19 with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and observed an overall sensitivity of 80% for IgM, 85% for IgG, and 90% for combined IgM or IgG more than 14 days after symptom onset. The fraction testing seropositive increased steadily over these first 14 days. Assay specificity was determined to be >99% based on testing of 263 pre–COVID-19 outbreak specimens and 114 asymptomatic blood donors during the early outbreak (Supplementary Table 1). We did not identify evidence of cross-reactivity (Supplementary Figure 3).

The overall seroprevalence (IgM+ and/or IgG+) was 31.5% (63/200) (Table 1). In detail, 17.5% were positive for both IgM and IgG (IgM+IgG+), 9.0% were IgM+IgG−, and 5.0% were IgM−IgG+. Overall, 26.5% of the cohort were IgM+ and 14.0% IgG+. Interreader agreement was 97%. Adjusting for the sensitivity and specificity of the assay, the estimated prevalence was 32.7% (90% credible interval, 26.4%–39.4%) for IgM, 16% (90% credible interval, 11.4%–21.0%) for IgG, and 32.8% (90% credible interval, 27.2%–38.8%) for combined IgM or IgG.

Seropositive participants had a female predominance, a higher median number of cohabiting children, symptomatology in the last 4 weeks, with a more distant onset of symptoms (Table 1). A reduced sense of smell or taste was reported in 28.6% vs 5.8% in the seropositive and seronegative participants, respectively.

In a multivariable regression model, the number of cohabiting children was an independent risk factor for seropositivity (odds ratio [OR], 1.057; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.001–1.117; P = .049; Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate analysis of the symptoms confirmed reduced sense of smell or taste as an independent risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity (OR, 1.519; 95% CI, 1.208–1.910; P < .001; Supplementary Table 3).

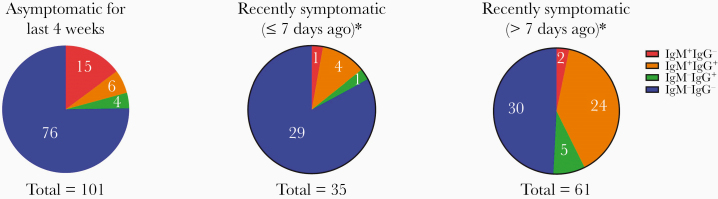

SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity was seen in 24.7% (25/101) of participants who were asymptomatic for the last 4 weeks, in 17.1% (6/35) who were symptomatic ≤7 days ago, and in 50.8% (31/61) who were symptomatic >7 days ago (Figure 1). Indeed, 20.8% (21/101) of participants who reported no symptoms in the preceding 4 weeks had a positive IgM antibody. The predominant seropositive pattern in those who reported no symptoms in the last 4 weeks was IgM+IgG− (15/25, 60%). Of the seropositive individuals reporting symptoms in the last 4 weeks, the IgM+IgG+ pattern predominated (28/37, 75.7%). In contrast, only 3 (8.1%) were IgM+IgG− (Figure 1). Five of 6 participants who were symptomatic in the last 7 days had already developed IgG.

Figure 1.

Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) results according to presence of and recency of symptoms. *Three persons who were previously symptomatic did not provide information on duration of symptoms (2 were IgM−IgG− and 1 was IgM+IgG+).

DISCUSSION

This study, performed in a convenience sample of currently asymptomatic adults at a busy commuter junction with no previous diagnosis of COVID-19, has the highest reported seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to date at 31.5%. This is 16.7-fold higher than the 1.89% case rate based on symptomatic PCR-based testing at that time. About half were asymptomatic for the last 4 weeks. These data indicate significant community transmission and asymptomatic infection, notwithstanding that this was not a population representative sample.

Massachusetts had the fifth highest number of COVID-19 cases in the United States [5] and has since recorded 100 000 confirmed cases [6]. Within Massachusetts, Chelsea remains the city with the highest cumulative case rate, at 7.23% (27 May 2020) [7]. Notably, 40.2% of 6742 tests performed were PCR positive [7]. The city of Chelsea is 4 miles from the city of Boston, and is the smallest city in Massachusetts at 2.21 square miles (sq mi) and a high population density at 17 959.28/sq mi in comparison to that of Massachusetts (883.64/sq mi) or Boston (16 381.27/sq mi) [8]. Based on population estimates from 2019, 66.9% were Hispanic or Latino, 45.5% were foreign born, and 70.3% spoke a language other than English at home [8]. The per capita income was $24 338, 18.8% persons were in poverty, and 17.5% held a bachelor’s degree and above [8]. Our results suggest that, at least amongst the tested population, many individuals may not be able to effectively socially distance due to high population density, continued work attendance as essential workers, poor access to care, and other socioeconomic barriers.

Classically, following viral infection, IgM detection is followed by IgG detection that persists even after IgM wanes. This study corroborates recent reports of serological testing in SARS-CoV-2 that challenge this dogma, with early detection of IgG (as early as day 4 after symptom onset and only 1 day later than IgM) and occasionally detectable IgG prior to IgM [9]. A recent preprint integrated data from 22 studies, finding significant variation in seroconversion with a mean of 12.6 and 13.3 days (standard deviation 5.7–5.8 days) post symptom onset for IgM and IgG, and notably both IgM and IgG may be detected as early as day 0 [10]. IgM titer peaked at around day 25 and decreased significantly shortly thereafter, whereas IgG peaked around day 25–27 and remained high for the reportable duration (up to 60 days) [10]. We noted that persons recently symptomatic had already developed IgG, and an IgM+IgG− response predominated in the 4-week asymptomatic group. While the latter may reflect early infection, it may also be plausible that their viral burdens were low, perhaps affecting the kinetics of class switching. If IgG is durable and protective against future reinfections, these asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic individuals may remain susceptible.

Of the passers-by tested here, 31.5% were seropositive and 26.0% were positive for IgM. Indeed 20.8% (21/101) of participants who reported no symptoms in the preceding 4 weeks were IgM positive, indicating a concerning significant burden of asymptomatic infection. Importantly, patients with COVID-19 have been shown to have a positive nasopharyngeal PCR for a median of 20 days in survivors (longest 37 days) [11]. Thus, there is likely a substantial pool of unrecognized, mobile, asymptomatic carriers in the community. The number of household contacts for the 63 seropositive participants totaled to 291, thus the pool of persons at risk is at least 5-fold. Indeed, 20 of the 47 participants (42%) who reported a known COVID-19 contact, demonstrated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. None had been previously tested, reflecting missed opportunities in contact-tracing strategies.

Several US population-based COVID-19 seroprevalence studies were conducted in March–April 2020 with varying methodologies, patient populations, and contrasting results. The Santa Clara study tested 1702 residents with the Premier Biotech IgM-IgG POC LFA, of whom 4.65% were seropositive [12]. Using the Abbott Architect IgG test, seroprevalence was 1.79% in 4865 Boise, Idaho residents [13] and 0.1% in 1000 blood donors in San Francisco Bay [14]. In contrast, this was 12.5% in 15 101 New York State and 22.7% in New York City residents based on dry-blood spots [15].

This mobile pilot study was limited by its sample size and random sampling; it was not designed to represent population structure. At the time of this study, there were no issued management guidelines for seropositive individuals. Furthermore, sensitivities around undocumented migrants compelled anonymized testing. Thus, we could not deliver, confirm, nor follow these results. We excluded children from this pilot, but our data suggest asymptomatic infection in children may play a role in transmission dynamics and deserves further study. We were careful to reiterate that serological tests were not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and remain a research tool. We emphasize that antibody detection does not equate to antibody function and the questions of reinfection and seroprotection remain unanswered. Acknowledging all the unknowns of herd immunity in this new disease, 31.5%, although high, is still far from the estimated seroprevalence consistent with herd protection.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated a remarkably high seroprevalence of 31.5% in a vulnerable urban population despite being currently asymptomatic. Serological testing can aid in understanding community prevalence, and uncover the substantial burdens of missed, mild, or asymptomatic infections, particularly in settings where PCR tests are limited. Enhanced testing, contact tracing, social distancing, and isolation are particularly needed in vulnerable communities.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We acknowledge the participants of the study. We thank the manager of the City of Chelsea, Tom Ambrosino, Mimi Graney, and the city volunteers and security personnel provided during the conduct of study.

Financial support. This work was support by Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Pathology; an anonymous donor; the Lambertus Family Foundation National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 AI146779); Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogenesis Readiness grant to A. G. S.; and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (training grant numbers T32 GM007753 to B. M. H. and T. M. C. and T32 AI007245 to J. F.). C. C. C. is supported by an Early Career Fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant number APP1092160).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: local meeting involving the City of Chelsea and the leadership of Partners Healthcare via Zoom meeting, 17 April 2020; and summarized on video for the community via the Chelsea Community Cable on 20 April 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYwIRweeHAE.

References

- 1. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cases in MA As of April 14, 2020.https://www.mass.gov/doc/confirmed-covid-19-cases-in-ma-by-citytown-january-1-2020-april-14-2020/download. Accessed 25 April 2020.

- 2. Li Z, Yi Y, Luo X, et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis [published online ahead of print 27 February 2020]. J Med Virol doi: 10.1002/jmv.25727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Black MA, Shen G, Feng X, et al. Analytical performance of lateral flow immunoassay for SARS-CoV-2 exposure screening on venous and capillary blood samples. medRxiv 20098426 [Preprint]. 13. May 2020. [cited 12 September 2020]. Available from: 10.1101/2020.05.13.20098426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larremore DB, Fosdick BK, Bubar KM, et al. Estimating SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and epidemiological parameters with uncertainty from serological surveys. medRxiv 20067066 [Preprint]. 15. April 2020. [cited 12 September 2020]. Available from: 10.1101/2020.04.15.20067066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nart J. COVID19 trend tracker.https://public.tableau.com/profile/jonas.nart#!/vizhome/COVID19_15844962693420/COVID19-TrendTracker. Accessed 12 September 2020.

- 6. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Dashboard - Monday, June 01, 2020.https://www.mass.gov/doc/covid-19-dashboard-june-1-2020/download. Accessed 12 September 2020.

- 7. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. COVID-19 Dashboard -Weekly COVID-19 Public Health Report Wednesday, May 27, 2020.https://www.mass.gov/doc/weekly-covid-19-public-health-report-may-27-2020/download. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- 8. United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts—Chelsea city, Massachusetts.https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/chelseacitymassachusetts. Accessed 12 September 2020.

- 9. Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med 2020; 26:845–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borremans B, Gamble A, Prager KC, et al. Quantifying antibody kinetics and RNA shedding during early-phase SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv 20103275 [Preprint]. 15. May 2020. [cited 12 September 2020]. Available from: 10.1101/2020.05.15.20103275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sood N, Simon P, Ebner P, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies among adults in Los Angeles County, California, on April 10–11, 2020. JAMA 2020; 323:2425–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bryan A, Pepper G, Wener MH, et al. Performance characteristics of the Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay and seroprevalence testing in Idaho. medRxiv 20082362 [Preprint]. 27. April 2020. [cited 12 September 2020]. Available from: 10.1101/2020.04.27.20082362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ng D, Goldgof G, Shy B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and neutralizing activity in donor and patient blood. Nat Commun 2020; 11:4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenberg ES, Tesoriero JM, Rosenthal EM, et al. Cumulative incidence and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in New York. Ann Epidemiol 2020; 48:23–29.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.