Abstract

Background

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic, many health care workers (HCWs) have been exposed to infected persons, leading to suspension from work. We describe a dynamic response to exposures of HCWs at Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem, to minimize the need for suspension from work.

Methods

We performed an epidemiological investigation following each exposure to a newly diagnosed COVID-19 patient or HCW; close contacts were suspended from work. During the course of the epidemic, we adjusted our isolation criteria according to the timing of exposure related to symptom onset, use of personal protective equipment, and duration of exposure. In parallel, we introduced universal masking and performed periodic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 screening for all hospital personnel. We analyzed the number of HCWs suspended weekly from work and those who subsequently acquired infection.

Results

In the 51 investigations conducted during March–May 2020, we interviewed 1095 HCWs and suspended 400 (37%) from work, most of them, 251 (63%), during the first 2 weeks of the outbreak. The median duration of exposure (interquartile range) was 30 (15–120) minutes. Only 5/400 (1.3%) developed infection, all in the first 2 weeks of the epidemic. After introduction of universal masking and despite loosening the isolation criteria, none of the exposed HCWs developed COVID-19.

Conclusions

Relatively short exposures of HCWs, even if only either the worker or the patient wears a mask, probably pose a very low risk for infection. This allowed us to perform strict follow-up of exposed HCWs in these exposures, combined with repeated testing, instead of suspension from work.

Keywords: COVID-19, exposure, health care workers, personal protective equipment, suspension from work

As of May 2020, Israel has experienced more than 19 000 cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19; 1777 cases/million) and more than 300 deaths (33 deaths/million) [1]. Jerusalem and its surrounding area are is the area with the highest prevalence of COVID-19 patients in Israel [2]. Health care workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of exposure to infected persons [3], and concern was raised early in the course of the epidemic that a substantial number of HCWs might need to be suspended from work. This could seriously affect the functioning work force available at the hospital [4, 5].

Understanding of the mode of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and strict guidelines for personal protective equipment (PPE) during direct patient contact and any interactions between HCWs in the hospital are essential for ensuring staff protection and safety [6]. Furthermore, immediate epidemiological investigation and, if needed, early suspension from work of exposed HCWs are needed in order to limit the spread of infection to and between HCWs and patients [7, 8].

In this article, we describe the outcomes of our dynamic response to exposures of HCWs to newly diagnosed positive patients or personnel, aimed at minimizing infection of HCWs and cross-transmission during the COVID-19 outbreak.

METHODS

Setting

The study was performed at the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center in Jerusalem, Ein-Kerem Campus, a 750-bed inpatient tertiary hospital, during the first 2 and a half months of the COVID-19 epidemic in Israel (from March 8 to May 23). Preparedness in the hospital included building 5 new dedicated wards for COVID-19 patients with 114 beds, including 44 intensive care beds. The emergency department assigned a dedicated and isolated area for triage and treatment of suspected COVID-19 patients. Every patient with relevant COVID-19 symptoms or an exposure to a known patient was assessed in this dedicated area and tested by a nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2. The Unit for Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) established guidelines for the use of PPE in the different settings and updated them periodically during the course of the epidemic, according to accumulating knowledge (Supplementary Table 1). Especially at the beginning of the epidemic, in the second week of March, many health care workers (HCWs) were exposed to COVID-19 patients in the hospital or outside. Immediate epidemiological investigations of exposed HCWs were initiated in order to break the chain of cross-transmission between HCWs as well as avoiding transmission from HCWs to patients, thus keeping maximal work force available.

Epidemiological Investigations

The IPC team got a notice of any positive COVID-19 HCW or patient in the hospital, either from the Ministry of Health (within a few hours after positive test results) or automatically from the hospital laboratory through the computerized information system (immediately upon verification of a positive test). To identify every possibly exposed HCW, a thorough epidemiological investigation was initiated immediately, even during evening shifts and weekends. The IPC team interviewed every such HCW and recorded the exact circumstances and duration of the encounter.

We defined close contact as exposure of at least 15 minutes, in a proximity of <2 m, to a COVID-19-positive person [9]. In case of a contact of <1 m, we considered even 5 minutes of exposure to be close contact. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines [10], wearing of PPE by the index case and/or the exposed HCW should be taken into consideration when deciding upon the need for home isolation of the exposed HCW. If both the index case and the HCW wore a face mask (surgical mask or N95 respirator), there was no need for isolation. The same decision was applied if the index case did not wear a face mask but the HCW wore a face mask and a face shield (Table 1).

Table 1.

Rules for Deciding Whether There Is a Need for Isolation After Close Contact With a COVID-19-Positive Person, [10] Based on the Use of Personal Protective Equipment (According to CDC Guidelines)

| Health Care Worker | Positive COVID-19 Person | Is There a Need for Isolation? |

|---|---|---|

| Face mask | Face mask | No |

| Face mask | - | Yes |

| - | Face mask | Yes |

| Face mask & face shield | - | No |

“Face mask” indicates either a surgical mask or N95 respirator.

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

aClose contact was defined as exposure of at least 15 minutes in proximity of <2 m to a COVID-19-positive person, or <1 m for at least 5 minutes.

During the course of the epidemic, with the evolving understanding of the infectivity and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we adjusted our criteria for home isolation of exposed HCWs (Supplementary Table 1). During the first 2 weeks of the epidemic in Israel, all exposed HCWs meeting the criteria for close contact were suspended from work for 14 days. After 2 weeks (on March 20), during which >250 HCWs were suspended from work, the need for home isolation was redefined according to the following principles: (1) If the index case was symptomatic at the time of exposure (eg, fever or chills, respiratory symptoms, loss of smell or taste), all close contacts were sent to home isolation for 14 days after the exposure date. (2) If the exposure occurred >4 days before the index case developed symptoms, as most patients are only infective within 4 days before symptoms [11], isolation was not required. (3) If the exposure occurred ≤4 days before the index case developed symptoms (if the index case never had symptoms within 4 days before the positive SARS-CoV-2 test), isolation was required for 10 days after the last exposure, and return to work was approved after a negative nasopharyngeal PCR test on day 10 [12]. These principles are summarized in Table 2. We asked every exposed HCW to inform us immediately in case of any evolving symptoms. Needless to say that every exposed employee who developed any suspicious symptoms was tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 and suspended from work while the results were pending. After relief of symptoms and a negative test result, the employee was allowed back to work.

Table 2.

Guiding Principles for Decision-Making Regarding Isolation of Healthcare Workers Following Exposure to Newly Diagnosed COVID-19 Patient

| Timing of Exposure | Decision |

|---|---|

| >4 days before the onset of symptoms (or date of test for asymptomatic) | No need for isolation, monitoring symptoms |

| Within 4 days before the onset of symptoms (or date of test for asymptomatic) | 10 days of home isolation, PCR test on day 10; if negative, stop isolation |

| While the index case is symptomatic | 14 days of home isolation |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Personal Protective Equipment Guidelines and Behavioral Etiquette

In the beginning of the epidemic in Israel (March 2020), we recommended the use of PPE for direct contact with suspected or COVID-19-positive patients, according to the CDC and Israeli Ministry of Health guidelines at that time [13, 14]. COVID-19-positive patients were isolated in designated wards, and all HCWs entering the area wore full airborne isolation PPE, for example, waterproof gown, gloves, N95 respirator, face shield, and head cover. Patients with suspected COVID-19, according to symptoms or because of exposure to a positive person, were put in isolation rooms, and HCWs entered the room while wearing surgical mask, face shield, disposable gown, and gloves. In these patients, in case of severe respiratory symptoms or aerosol-producing procedures, PPE was upgraded to full airborne protection as described above. In the light of many exposed HCWs, during the last week of March 2020, the IPC team required the use of surgical masks by hospital personnel during every patient contact. In addition, staff meetings were restricted to 10 attendees and allowed only while adhering to rules of social distancing, and interaction between staff during shifts was kept to a minimum. In parallel, a routine periodic screening program for SARS-CoV-2 of all HCWs was introduced at the hospital [15]. This included summoning all employees for PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 performed on nasopharyngeal swabs. The employees were asked to undergo a second test after 5 days. Periodic screening of all HCWs is still being employed at the hospital currently. On April 7, we changed our policy to universal masking of HCWs and visitors at all times and of patients during any contact with an HCW.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics for all investigations performed on HCWs who were exposed to a COVID-19 patient or colleague and their outcomes. Categorical variables are presented with percentages, and continuous variables are presented with median and interquartile range (IQR). We describe the number of HCWs suspended weekly from work and those subsequently acquiring infection over the course of the epidemic. Additionally, we examine the effect of the changing strategies of PPE and criteria for suspension from work on these outcomes. We used the extended Mantel-Haenszel test to compare the rates of HCWs whom we sent to home isolation in each investigation before and after the demand for masking of HCWs (WinPepi, version 11.60). Significance was 2-tailed and determined at P < .05.

RESULTS

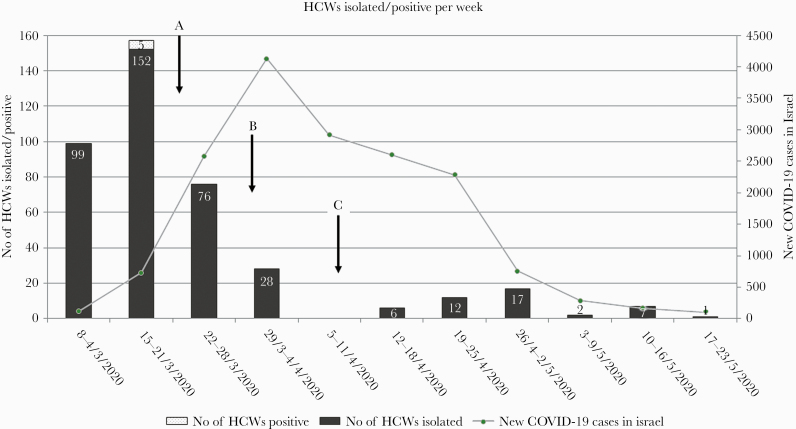

Between March 8 and May 23 (11 weeks), we performed 51 exposure investigations. In 23/51 (45%), the index case was an HCW, and in 28/51 (55%) a patient (emergency department, 8 [29%]; delivery room, 7 [25%]; medical, 8 [29%]; surgical, 3 [11%]; outpatient clinics, 2 [7%]). In 5 out of these exposure investigations (10%), the index case was asymptomatic throughout the course of his disease. Altogether, we interviewed 1095 HCWs (Table 3). Out of these, 400 (37%) HCWs had close contact as defined by the CDC [10]. Most of these were relatively short exposures (median [IQR], 30 [15–120] minutes). In most of these exposures, either the HCW and/or the index case was not fully protected as defined by the CDC guidelines (both without a mask, 360 [90%]; only 1 with a mask, 36 (9%); both masked but exposure >3 hours, 4 [1%]). These workers were suspended from work and sent to home isolation. The vast majority of HCWs, 251/400 (63%), were sent to home isolation during the first 2 weeks of the outbreak. Of all HCWs sent to home isolation following these investigations, only 5/400 (1.3%) developed infection with COVID-19 during the period of isolation, all at the very beginning of the epidemic (Figure 1). None of the HCWs investigated because of potential exposure but not sent to isolation developed COVID-19.

Table 3.

Detailed Results of 51 Investigations of Health Care Workers’ Exposures to COVID-19-Positive Patients or Colleagues During 11 Weeks of the Pandemic

| Sector | Investigated | Isolated | Infected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Average per Investigation (Range) | No. (%)a | Average per Investigation (Range) | No. (%)b | |

| Nurse | 545 | 10.7 (0–47) | 205 (38) | 4.0 (0–47) | 2 (0.97) |

| Physician | 292 | 5.7 (0–23) | 99 (34) | 1.9 (0–16) | 2 (2.02) |

| Other HCW | 258 | 5.1 (0–34) | 96 (37) | 1.9 (0–21) | 1 (1.04) |

| Total | 1095 | 21.5 (0–70) | 400 (37) | 7.8 (0–70) | 5 (1.25) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HCW, health care worker.

aPercentage of HCWs isolated out of those investigated.

bPercentage of HCWs who became positive out of those isolated.

Figure 1.

Number of health care workers (HCWs) who were suspended from work (gray) or had a positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 test (dotted) each week, March–May 2020. The black arrows show the changes in personal protective equipment policy during the epidemic: (A) face mask during contact with every patient and during meetings of HCWs lasting 15 minutes or more (March 20); (B) avoiding unnecessary contact between HCWs (eg, meetings, shift transfer; March 29); (C) universal masking of HCWs and visitors at all times and of patients during any contact with an HCW (April 7) (Supplementary Table 1). The line shows the number of new coronavirus disease 2019 cases every week in Israel for comparison (data were taken from the Israel Ministry of Health official website: https://govextra.gov.il/ministry-of-health/corona/corona-virus/).

As our hospital performed routine screening for SARS-COV-2 on all HCWs, we were able to check and ascertain that we did not miss any positive HCW whom we might not have included in our investigations and follow-up. The compliance rate with routine testing among HCWs included in our investigations was 6487/7014 (92%).

After the IPC order for the need for a face mask for HCWs during every patient contact (March 20), the number of HCWs needed to be suspended from work declined sharply from a mean of 17.11 per investigation before the change to 2.79 per investigation after it (P = .001). Despite redefinition and loosening the criteria for suspension from work on March 22, no HCW who was exposed after this change was infected until the end of the study period (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Health care workers are at increased risk of acquiring COVID-19 from unrecognized patients or colleagues during work [16, 17]. At the very beginning of the epidemic in Israel, the IPC team of our hospital started epidemiological investigations of every exposure to a newly diagnosed SARS-CoV-2-positive patient or HCW. The first investigations resulted in the need to suspend a large number of HCWs from work, requiring home isolation. Serious concern was raised that departments would need to be totally shut down, threatening the ability of the hospital to keep functioning over time. As soon as we learned in mid-March 2020, from the CDC guidelines at that time, that wearing PPE (face mask with or without face shield) could reduce the need for excluding exposed HCWs from work [14], we updated our rules of protection. We introduced universal masking for hospital personnel, patients, and visitors and social distancing between HCWs. Later on, this approach was suggested also in the literature [6]. Since then, the number of HCWs whom we needed to suspend from work decreased significantly. As shown in figure 1, this decline happened while the epidemic in Israel was still on the rise. A single report from the Minnesota Department of Health (USA) also showed a reduction in HCW infections in the hospital following the introduction of universal masking [18].

In addition, and according to new accumulating knowledge, we redefined the criteria for suspension from work and duration of isolation required [14]. We differentiated between exposures to symptomatic or asymptomatic index cases and reduced the duration of home isolation needed after exposure to an asymptomatic index case. As 95% of exposed people who become infected do so within 10 days of exposure, we performed a SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal test on day 10 for isolated workers, before allowing them to return to work [12]. In so doing, we further reduced the number of HCWs excluded from work at any given time.

During 51 epidemiological investigations performed, out of 1095 potentially exposed HCWs whom we thoroughly interviewed, we defined 400 as close contacts, prompting suspension from work. Out of these, only 5 developed clinical signs of infection with SARS-CoV-2, all in the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak. Although we narrowed the criteria for isolation, none of the HCWs investigated, but not isolated, developed clinical signs of infection with COVID-19. Owing to the periodic universal screening of all HCWs performed at our hospital, we were assured that there were no eventual asymptomatic HCWs among those investigated or isolated. Additionally, the proactive screening allowed us to assume that we probably did not miss any close contacts during our investigation process who potentially could become positive.

Furthermore, the results of this study raise the question of whether the criteria for isolation were still too rigorous, as, after the initial phase, none of the HCWs excluded from work developed COVID-19. In light of these findings and in the presence of universal masking and social distancing, it might be worthwhile to consider substitution of suspension from work of exposed HCWs with rigorous follow-up of symptoms and repeated testing on days 5 and 10 after exposure. This approach was recently studied in a mathematical model performed by Peak et al. [19].

There are some limitations to this study: Due to the retrospective nature of the epidemiological investigations, there is a recall bias, and hence, in some cases it was not trivial to define each contact unequivocally. Our criteria for home isolation after exposure may need further specification. Accumulating knowledge on the infectivity of asymptomatic or presymptomatic patients might shed light on this issue [20]. In addition, despite periodic screening of all HCWs, as we did not test them every day, we still might have missed asymptomatic positive personnel; however, we assume that that chance is negligible. Our experience might be valid in hospitals with dedicated COVID-19 departments and universal masking, and we assume that this by now is the standard of care in most countries.

In conclusion, after introducing universal masking for HCWs, patients, and visitors, as well as social distancing, none of the exposed HCWs developed COVID-19. Based on the results of our study, we assume that relatively short exposures of HCWs, even if only either the worker or the patient wore a mask, probably pose a very low risk of infection. This allows us to consider performing strict follow-up of exposed HCWs for symptoms, together with repeated PCR testing, instead of suspending them from work.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Hadassah COVID-19 Investigations Working Group (presented alphabetically). Adiel Cohen, Ayelet Favor, Ilana Gross, Shahar Luski, Miriam Ottolenghi, Elchanan Parnasa, Nechamat Reichman, Naama Ronen, Einat Zeidel, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Potential conflict of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Patient consent. Our study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

Contributor Information

Hadassah COVID-19 Investigations Working Group:

Adiel Cohen, Ayelet Favor, Ilana Gross, Shahar Luski, Miriam Ottolenghi, Elchanan Parnasa, Nechamat Reichman, Naama Ronen, and Einat Zeidel

References

- 1. Coronavirus Worldometer Israel. Published 2020. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/israel/. Accessed 14 June 2020.

- 2. National Knowledge and Information Center for the Battle of Corona About: Israeli Government: Ministry of Health; Updated May 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/daily-report-16052020/he/daily-report_daily-report-16052020.pdf (Hebrew). Accessed 21 May 2020.

- 3. Zhou P, Huang Z, Xiao Y, et al. Protecting Chinese healthcare workers while combating the 2019 novel coronavirus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020; 41:745–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagesh S, Chakraborty S. Saving the frontline health workforce amidst the COVID-19 crisis: challenges and recommendations. J Glob Health 2020; 10:010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willan J, King AJ, Jeffery K, Bienz N. Challenges for NHS hospitals during COVID-19 epidemic. BMJ 2020; 368:m1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klompas M, Morris CA, Sinclair J, et al. Universal masking in hospitals in the Covid-19 era. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pung R, Chiew CJ, Young BE, et al. ; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team Investigation of three clusters of COVID-19 in Singapore: implications for surveillance and response measures. Lancet 2020; 395:1039–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Contact tracing: public health management of persons, including healthcare workers, having had contact with COVID-19 cases in the European Union Updated 25 February 2020 Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-public-health-management-contact-novel-coronavirus-cases-EU.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 9.Israel Ministry of Health. COVID-19 guidelines, procedures and information for professionals Updated 10 April 2020 Available at: https://govextra.gov.il/media/16100/mmk-202607320.pdf (Hebrew). Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. guidance for risk assessment and work restrictions for healthcare personnel with potential exposure to COVID-19 Updated on 19 May 2020 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 11. He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020; 26:672–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172:577–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel Ministry of Health. COVID-19 guidelines, procedures and information for professionals Updated 10 March 2020 Available at: https://govextra.gov.il/media/17976/coronavirus_med_guidelines.pdf (Hebrew). Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings Updated on 18 May 2020 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Accessed 21 May 2020.

- 15. Oster Y, Wolf DG, Olshtain-Pops K, et al. Proactive screening approach for SARS-CoV-2 among healthcare workers [published online ahead of print August 18, 2020]. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; S1198-743X(20)30491–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, Buiting AGM, Pas SD, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of health care workers with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 in 2 Dutch hospitals during an early phase of the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e209673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lai X, Wang M, Qin C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e209666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minnesota Department of Health, responding to and monitoring COVID-19 exposures in health care settings Updated 13 July 2020 Available at: https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/hcp/response.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2020.

- 19. Peak CM, Kahn R, Grad YH, et al. Individual quarantine versus active monitoring of contacts for the mitigation of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakurai A, Sasaki T, Kato S, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:885–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.