Abstract

Summary

Identification of the amino-acid motifs in proteins that are targeted for post-translational modifications (PTMs) is of great importance in understanding regulatory networks. Information about targeted motifs can be derived from mass spectrometry data that identify peptides containing specific PTMs such as phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and acetylation. Comparison of input data against a standardized ‘background’ set allows identification of over- and under-represented amino acids surrounding the modified site. Conventionally, calculation of targeted motifs assumes a random background distribution of amino acids surrounding the modified position. However, we show that probabilities of amino acids depend on (i) the type of the modification and (ii) their positions relative to the modified site. Thus, software that identifies such over- and under-represented amino acids should make appropriate adjustments for these effects. Here we present a new program, PTM-Logo, that generates representations of these amino acid preferences (‘logos’) based on position-specific amino-acid probability backgrounds calculated either from user-input data or curated databases.

Availability and implementation

PTM-Logo is freely available online at http://sysbio.chula.ac.th/PTMLogo/ or https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/PTMLogo/.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

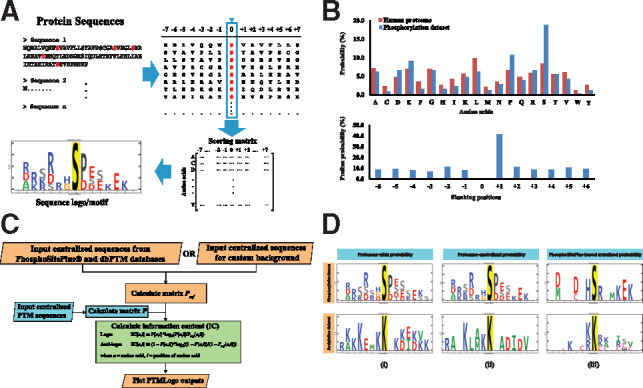

Protein mass spectrometry has undergone a dazzling increase in sensitivity, allowing deeper and deeper profiling of post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, acetylation and methylation, in biological tissues. In general, a proteomic dataset addressing a particular amino-acid modification consists of a list of peptide sequences that includes the amino acids flanking the modification (Fig. 1A). These sequences provide information relevant to the biological mechanism of the modification. For example, protein kinases exhibit preferences for certain flanking amino acids and this prior information helps to determine the kinases responsible for phosphorylation seen in a given phospho-proteomic experiment. To analyze the data, the list of sequences in a given dataset needs to be processed to identify position-dependent amino acid probabilities that are significantly greater (or smaller) than ‘expected values.’ The expected values are generally represented by a set of background amino acid probabilities, i.e. a background probabilities vector. Observed values are then examined against these expected values to determine enrichment for particular amino acids at positions flanking the modified site; these enrichments are graphically depicted as ‘logos’ (Fig. 1A). The simplest approach is to use the general probability of each amino acid in all proteins coded by the genome (here referred to as proteome-wide probabilities) (Douglass et al., 2012; Maddelein et al., 2015; Thomsen and Nielsen, 2012). However, data from our lab (Isobe et al., 2017) illustrates pitfalls with this approach. Here, analysis of mass spectrometry data showed that proline was present in phospho-enriched peptides at a level 70% higher than the total proteome (Fig. 1B). In this particular case, proline would be over-represented in calculations of kinase preference. An appropriate background should thus adjust for this distribution of amino acids. Another pitfall is seen in the fact that proline was found to be C-terminal adjacent to the phosphorylation site in 41% of all peptides. Even with the previous adjustment to proteome-wide probabilities, proline would still be over-represented at the +1 position relative to the phosphorylated site. Again, an adjustment should be made, with amino acid probabilities at each position being considered. It is therefore critical to adjust appropriately for position-specific amino acid probabilities. While the concept of position-specific probabilities dates back at least 20 years (Linding et al., 2007; Obenauer et al., 2003), we rigorously demonstrate the importance of using these probabilities as backgrounds against which input data is evaluated (see Supplementary Material). A final pitfall is illustrated in the finding that tyrosine and serine/threonine phosphorylation should be regarded as distinct modifications (Sharma et al., 2014). In this case, tyrosine-centered phosphorylation data should be separated from serine/threonine data prior to logo generation.

Fig. 1.

The work flow for generating sequence logos from centralized sequences (A). Bias of amino acid probabilities in phospho-enriched data (Isobe et al., 2017) (B). The PTMLogo workflow for generating sequence logos (C). The effects of different position specific backgrounds on the generated sequence logo (D, see Supplementary Material)

Here, we present new software, PTM-Logo, designed to determine significantly enriched amino acids flanking the modified site using appropriate position-specific backgrounds. Users are able to use their own data to create backgrounds or select from a variety of our predefined backgrounds. The program allows the option of automatic separation of serine-, threonine-, tyrosine- and lysine-centered input data.

2 Examples

An important feature of PTM-Logo is the ability to use predefined backgrounds against which input data is evaluated. One consideration in constructing these backgrounds concerns the ‘accessibility’ of potentially modified amino acids to modifying enzymes. Logically, inaccessible protein sequences should not be incorporated into backgrounds, as the modifying enzymes would not ‘see’ such sequences. We thus use known PTM sites from public databases (Hornbeck et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016) as proxies for accessible regions in constructing new backgrounds.

We generated logos based on three actual inputs from mass spectrometry datasets. The first is a phosphorylation dataset (Feric et al., 2011), the second is an acetylation dataset (Claxton et al., 2013) and third is a PKA knockout dataset (Isobe et al., 2017). The results are summarized in Supplementary Material.

3 Implementation and availability

PTM-Logo is implemented using the Java development kit (JDK 12.0.1). Installation files and databases are available online at http://sysbio.chula.ac.th/PTMLogo/ or https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/PTMLogo/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members in the Center of Excellence in Systems Biology, Chulalongkorn University and Epithelial Systems Biology Laboratory, NHLBI, National Institutes of Health for testing software, sharing knowledge, encouragement, criticism and valuable advice.

Funding

T.S. is supported by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Grant Number RA61/103. M.A.K. is supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the NHLBI, NIH (Projects HL-001285 and HL-006129). K.H. is supported by Ratchadapisek Somphot Fund for Postdoctoral Fellowship, Chulalongkorn University. T.P. is supported by Chulalongkorn Academic Advancement into Its 2nd Century (CUAASC) Project and Thailand Research Fund (RSA6280026).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Claxton J.S. et al. (2013) Endogenous carbamylation of renal medullary proteins. PLoS One, 8, e82655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass J. et al. (2012) Identifying protein kinase target preferences using mass spectrometry. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol., 303, C715–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feric M. et al. (2011) Large-scale phosphoproteomic analysis of membrane proteins in renal proximal and distal tubule. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol., 300, C755–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck P.V. et al. (2015) PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res., 43, D512–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.Y. et al. (2016) dbPTM 2016: 10-year anniversary of a resource for post-translational modification of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 44, D435–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe K. et al. (2017) Systems-level identification of PKA-dependent signaling in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, E8875–E8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linding R. et al. (2007) Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell, 129, 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddelein D. et al. (2015) The iceLogo web server and SOAP service for determining protein consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 43, W543–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer J.C. et al. (2003) Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 3635–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K. et al. (2014) Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep., 8, 1583–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M.C., Nielsen M. (2012) Seq2Logo: a method for construction and visualization of amino acid binding motifs and sequence profiles including sequence weighting, pseudo counts and two-sided representation of amino acid enrichment and depletion. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, W281–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.