Abstract

Cancer survivors are at risk for poor subjective well-being, but the potential beneficial effect of daily spiritual experiences is unknown. Using data from the second and third wave of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study, we examined the extent to which daily spiritual experiences at baseline moderate the association between subjective well-being at baseline and approximately 10 years later in cancer survivors (n = 288). Regression analyses, controlled for age, educational attainment, and religious/spiritual coping, showed that daily spiritual experiences moderated the association between life satisfaction at baseline and follow-up. Specifically, high spiritual experiences enhanced life satisfaction over time in cancer survivors with low life satisfaction at baseline. Also, daily spiritual experiences moderated the association between positive affect at baseline and follow-up, though this moderating effect was different for women and men. No moderating effect emerged for negative affect.

Keywords: spiritual experiences, gender, cancer survivors, life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, moderation

Coping with and recovering from a life-threatening illness, such as cancer, is a major stressor. There is by now abundant evidence that cancer survivors report poorer health-related quality of life and life satisfaction, greater distress, and more psychological problems relative to those with no cancer history (e.g., Baker, Haffer, & Denniston, 2003; Hewitt, Rowland, & Yancik, 2003; Rabin et al., 2007; Seitz et al., 2011). Cancer survivors often highlight the importance of religiosity or spirituality as resources for coping with cancer and its treatment (e.g., Gall & Cornblat, 2002; Henderson, Gore, Davis, & Condon, 2003; Renz et al., 2015; Simon, Crowther, & Higgerson, 2007). However, findings from studies examining the impact of religiosity or spirituality on cancer survivors’ well-being are mixed. For instance, Stefanek, McDonald, and Hess (2005) reviewed studies with cancer survivors and found several showing no substantial association between spirituality and aspects of quality of life and life satisfaction. Likewise, the review by Schreiber and Brockopp (2012) revealed inconclusive results for the relationship between religious practices or coping and components of well-being, including quality of life, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being, with some studies showing a positive effect and others showing no effect. Finally, Thuné-Boyle, Stygall, Keshtgar, and Newman (2006) reviewed potential beneficial or harmful effects of religious/spiritual coping with cancer and found mixed results for quality of life or life satisfaction. It has been argued that these mixed findings are due to the way how spirituality or religiosity and religious/spiritual coping are conceptualized and measured and the preponderance of cross-sectional research on this topic (e.g., Stefanek et al., 2005; Thuné-Boyle et al., 2006).

Underwood and Teresi (2002) assume that “mundane” or ordinary spiritual experiences of the transcendent, a connection with other people, or a connection with nature might be particularly salient for one’s health. They developed the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Fetzer Institute, 1999; Underwood, 2006; Underwood & Teresi, 2002) that attempts to measure intrapsychic experiences rather than particular beliefs or behaviors regardless of specific manifestations of religiosity. Specifically, the authors suggest that certain feelings tapped by the DSES, such as inner peace or harmony, may reduce feelings of psychological stress, thereby moderating the link between stressors and subsequent health and well-being outcomes. In addition, they posit that these experiences may reduce feelings of anxiety and depression and enhance personal morale and, thereby, elevate mood and promote positive psychological outcomes. While daily spiritual experiences seem to be conceptually different from other types of religiosity, there is some evidence that they correlate strongly with positive religious coping, private religious practices, religious intensity, and spiritual values and beliefs (Idler et al., 2003; Neff, 2006).

Research on well-being is theoretically derived from two perspectives, the hedonic and the eudaimonic approach (Ryan & Deci, 2001). The hedonic approach focuses on happiness or pleasure and defines subjective well-being in terms of greater positive affect, lower negative affect, and greater life satisfaction (Diener, 1984); each of which have been found to be moderately stable over long periods of time (e.g., Lucas & Donnellan, 2007; Watson & Walker, 1996). In contrast, the eudaimonic approach focuses less on affective experiences like happiness, distress or frustration and more on qualities of life presumed to give life meaning such as having deep intimate relationships, having meaning in life, and some semblance of mastery over personal situations (Ryff, 1989). In the present article, we focus on subjective well-being as described in the hedonic approach.

The theory of religiosity as a tertiary adaptation suggests that a person’s well-being is affected by his or her religiosity (Kanazawa, 2015). There is now ample evidence that religious people report higher levels of subjective well-being (Ellison, 1991; Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011; Dolan, Peasgood, & White, 2008). However, relatively few studies have examined the relationship between daily spiritual experiences and subjective well-being, and all were cross-sectional. Underwood and Teresi (2002) analyzed data of young adults from the Loyola study and of women from the Chicago site of the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN) study and found that in the Loyola study more frequent daily spiritual experiences were associated with higher levels of positive affect, but no association was found for negative affect. Results from the SWAN indicated that greater daily spiritual experiences were associated with better quality of life and fewer depressive symptoms. Using cross-sectional data from the 1998 US General Social Survey, Maselko and Kubzansky (2006) found that greater frequency of spiritual experiences was associated with greater happiness with life among both men and women. Ellison and Fan (2008) used data from the 1998 and 2004 US General Social Survey and reported that greater frequency of daily spiritual experiences was associated with greater actual happiness and general excitement with life. However, there was no evidence linking daily spiritual experiences with negative aspects of well-being, such as psychological distress. These authors further analyzed theistic (e.g., feeling God’s presence) and non-theistic daily spiritual experiences (e.g., a connection to all of life) separately and found that psychological distress was independent on the object (i.e., theistic versus not) of daily spiritual experiences.

Only one study could be located that focused on the putative benefit of daily spiritual experiences for cancer survivors. Park, Edmondson, Hale-Smith, and Blank (2009) studied young-adult cancer survivors and found that greater frequency of daily spiritual experiences was related to greater performance of health behaviors, such as following doctor’s advice, getting five servings of fruits or vegetables a day, or drinking no or only a moderate amount of alcohol. The current study aimed to add to this literature by determining the extent to which daily spiritual experiences and gender relate to cancer survivors’ subjective well-being over time. Using the MIDUS II data, Greenfield, Vaillant, and Marks (2009) found that more frequent spiritual experiences were related to higher levels of positive affect and lower levels of negative affect in the general population. In line with this finding and those from previous research (e.g., Ellison & Fan, 2008; Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006; Underwood & Teresi, 2002), we hypothesized that daily spiritual experiences at baseline are positively associated with cancer survivors’ well-being at follow up, and that daily spiritual experiences at baseline moderate the change in well-being between baseline and follow up. Consistent with the hedonic conceptualization, life satisfaction and positive and negative affect are used to measure well-being. We did not formulate a hypothesis for negative affect due to mixed findings.

Method

Participants

Data are from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS; Radler & Ryff, 2010; Ryff et al., 2018) study, a national longitudinal study of health and well-being. Participants were a sample of English-speaking adults aged 25 to 74 years who were recruited via random digit dialing in 1995–1996 (MIDUS I, n = 7108) and then followed-up in 2004–2006 (MIDUS II, n = 4963), and again in 2013–2014 (MIDUS III, n = 3294). The current study used data from MIDUS II and III because daily spiritual experiences were not measured at MIDUS I (see Ryff et al., 2018; for a list of the variables that were collected). Participants who responded affirmatively to the question “Have you ever had cancer?” at both time points (i.e., MIDUS II and III) in the telephone interview and with complete data for all study variables were selected for the analyses, resulting in a sample of 288 adults. The vast majority (96.2%) identified as White, 0.7% as Black or African American, 0.3% as Native American or Alaska Native Aleutian Islander/Eskimo, 2.4% as other, and 0.3% refused to answer the question.

Procedure and measures

Religious/Spiritual Coping

Spiritual or religious coping was assessed by two questions: “When you have problems or difficulties in your family, work, or personal life, how often do you seek comfort through religious or spiritual means such as praying, meditating, attending a religious or spiritual service, or talking to a religious or spiritual advisor?” and “When you have decisions to make in your daily life, how often do you ask yourself what your religious or spiritual beliefs suggest you should do?”. The participants were asked to respond on a 4-point scale ranging from “often” (1) to “never” (4). The two items were reverse-coded and summed up so that higher scores indicate greater religious or spiritual coping (Cronbach’s α = .87).

Daily spiritual experiences

Daily spiritual experiences were measured by five items taken from the original 16-item Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES; Fetzer Institute, 1999; Underwood, 2006; Underwood & Teresi, 2002). The original scale was designed to measure ordinary or “mundane” spiritual experiences as opposed to mystical experiences (e.g., near death experiences, hearing voices). In this shorter version, items referring explicitly to “God”, “religion”, “creation”, and “blessings” were excluded. The five items were: “A feeling of deep inner peace or harmony,” “A feeling of being deeply moved by the beauty of life,” “A feeling of strong connection to all of life,” “A sense of deep appreciation,” and “A profound sense of caring for others.” Participants were asked to indicate how often, on a daily basis, they have those spiritual experiences on a 4-point scale from “often” (1) to “never” (4). All items were reverse-coded and summed up so that higher scores indicate more daily spiritual experiences (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction across domains was assessed with 6 items, namely life overall, work, health, relationship with spouse/partner, relationship with children, and financial situation. The first five items were taken from Prenda and Lachman (2001) and the sixth item was added to include satisfaction with the financial situation. Participants were asked to rate each domain on a 11-point scale ranging from “the worst possible” (0) to “the best possible” (10) for these days. The scores for relationship with spouse/partner and relationship with children were averaged to create one “item” which reflects satisfaction with the family relationships. Then, this score was used along with the remaining four items to calculate an overall mean score with higher scores indicating higher levels of overall life satisfaction (Cronbach’s α = .64 at baseline and .62 at follow-up). In the case that participants did not have some aspect of the items (e.g., no children), the score was calculated using the mean of the remaining items.

Positive Affect

Positive affect was measured with 4 items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The items were: “enthusiastic”, “attentive”, “proud”, and “active”. The participants were asked to rate the extent to which they have experienced each particular emotion during the past 30 days on a 5-point scale ranging from “all of the time” (1) to “none of the time” (5). All items were reverse-coded and a mean score was calculated with higher scores reflecting higher levels of positive affect (Cronbach’s α = .86 at baseline and .85 at follow-up).

Negative Affect

Negative affect was measured with 5 items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The items were: “afraid”, ‘jittery”, “irritable”, “ashamed” and “upset”. The participants were asked to rate the extent to which they have experienced each particular emotion during the past 30 days on a 5-point scale ranging from “all of the time” (1) to “none of the time” (5). All items were reverse-coded and a mean score was calculated with higher scores indicating higher levels of negative affect (Cronbach’s α = .79 at baseline and .76 at follow-up).

Statistical analyses

The PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018) was used to assess the moderating role of spiritual experiences and gender on the relationship between subjective well-being at baseline and approximately 10 years later in cancer survivors. Three longitudinal models were estimated, all using spiritual experiences at baseline as moderator. The first model tests the effect of life satisfaction over time, the second model positive affect, and the third model negative affect. In addition, a binary group variable was included as second moderator to compare women (coded −1) and men (coded 1) since some studies found that women have higher DSES scores than men (Kalkstein & Tower, 2009; Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006; Skarupski, Fitchett, Evans, Mendes, & Leon, 2010). The continuous predictor and moderator variables were mean-centered prior to the analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) and then multiplied to form the interaction terms. In addition to controlling for the other outcome variables at baseline (e.g., controlling for positive and negative effect in the model with life satisfaction), we controlled for participants’ age, educational attainment, and religious/spiritual coping. Previous research suggests that educational attainment is associated with less frequent daily spiritual experiences (Kalkstein & Tower, 2009) and that pleasant affect tends to decline with age, but not life satisfaction and negative affect (Diener & Lucas, 2000). Using an alpha level of .05 and a power level of .80, the current sample size of 288 cancer survivors allows the detection of an incremental effect of as small as ΔR2 = .040 or f2 = .042 (GPower; Erdfelder, Faul, & Buchner, 1996).

Results

Preliminary analyses

The types of cancer for men and women reported at follow-up are given in Table 1. The most frequent types of cancer were skin/melanoma and prostate cancer for men and skin/melanoma and breast cancer for women.

Table 1.

Type of cancer for the men and women at follow-up

| Type of cancer | Men (n = 108) |

Women (n = 180) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Prostate | 34 | 31.5 | - | - |

| Cervical | - | - | 14 | 7.8 |

| Ovarian | - | - | 4 | 2.2 |

| Uterine | - | - | 18 | 10.0 |

| Breast | 0 | 0.0 | 59 | 32.8 |

| Colon | 8 | 7.4 | 8 | 4.4 |

| Lung | 2 | 1.9 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Lymphoma/leukemia | 3 | 2.8 | 8 | 4.4 |

| Skin/melanoma | 48 | 44.4 | 71 | 39.4 |

| Other | 25 | 23.1 | 37 | 20.6 |

Mean age at baseline was 63 years (SD = 11.32) for men and 60 years (SD = 10.25) for women (Table 2). The mean level of education at baseline was 8 (SD = 2.68) for men and 7 (SD = 2.69) for women, referring to “graduated from a two-year college or vocational school, or associate’s degree” and “3 or more years of college, no degree yet”, respectively. Several gender differences emerged, with men being significantly older on average and reporting higher levels of life satisfaction at baseline and women reporting, in average, higher levels of religious/spiritual coping and spiritual experiences than men (see Table 2). The effect sizes of these significant differences ranged from 0.24 to 0.38 and were considered small.

Table 2.

Correlations for the men above and the women below, means, standard deviations, and empirical ranges for the study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | −.24* | .11 | .38** | .32** | .10 | .23* | .03 | −.21* | −.07 |

| 2. Education | −.09 | - | −.04 | −.02 | −.04 | .12 | −.10 | .10 | .13 | .06 |

| 3. Religious/Spiritual Coping | .07 | −.08 | - | .44** | .15 | .04 | .09 | .10 | .02 | .00 |

| 4. Spiritual Experiences Baseline | .31** | −.01 | .38** | - | .39** | .21* | .38** | .27** | −.23* | −.17 |

| 5. Life Satisfaction Baseline | .27** | .19** | .08 | .27** | - | .61** | .57** | .38** | −.47** | −.43** |

| 6. Life Satisfaction Follow-up | .10 | .18* | .11 | .23** | .51** | - | .30** | .44** | −.31** | −.43** |

| 7. Positive Affect Baseline | .33** | .05 | .01 | .36** | .41** | .27** | - | .55** | −.53** | −.43** |

| 8. Positive Affect Follow-up | .13 | −.08 | .09 | .25** | .24** | .43** | .57** | - | −.24* | −.31** |

| 9. Negative Affect Baseline | −.28** | −.12 | .01 | −.22** | −.51** | −.37** | −.41** | −.31** | - | .57** |

| 10. Negative Affect Follow-up | −.17* | −.14 | −.05 | −.15* | −.37** | −.53** | −.22** | −.37** | .62** | - |

| Men | ||||||||||

| M | 62.53 | 7.71 | 5.69 | 15.60 | 7.78 | 7.51 | 3.64 | 3.45 | 1.47 | 1.44 |

| SD | 11.32 | 2.68 | 2.13 | 3.15 | 1.16 | 1.47 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.43 |

| Range | 35–83 | 3–12 | 2–8 | 5–20 | 3.8–10 | 3–10 | 1.3–5 | 1–5 | 1–3 | 1–3 |

| Women | ||||||||||

| M | 59.91 | 7.11 | 6.29 | 16.76 | 7.46 | 7.45 | 3.58 | 3.50 | 1.58 | 1.50 |

| SD | 10.25 | 2.69 | 1.95 | 2.87 | 1.15 | 1.24 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| Range | 37–81 | 2–12 | 2–8 | 6–20 | 4.3–10 | 2.2–10 | 1.5–5 | 1–5 | 1–3.8 | 1–5 |

| t test | 2.02* | 1.84 | 2.43* | 3.18** | 2.31* | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 1.77 | 1.01 |

| df | 286 | 286 | 285 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 273.52 |

| Cohen’s d | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

Note. M = Mean, SD = Standard deviation. Possible ranges: 1–12 for highest level of education completed (1 = no school/some grade school, 12 = PhD, MD, or other professional degree), 2–8 for religious/spiritual coping, 5–20 for spiritual experiences, 0–10 for life satisfaction, 1–5 for positive affect, 1–5 for negative affect.

p < .05.

p < .01. (2-tailed).

Table 2 also presents the product-moment correlations among the study variables for women and men as well as the descriptive statistics. For both, women and men, the correlations at baseline of spiritual experiences with life satisfaction and with positive affect were positive, while the correlation with negative affect was negative, ranging from small to medium in size.

Moderation Analyses

The results of the three moderation models for life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the regression analyses for cancer survivors

| Life Satisfaction Follow-up |

Positive Affect Follow-up |

Negative Affect Follow-up |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE |

| Age | −0.010 | 0.007 | −0.009* | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Education | 0.050* | 0.025 | −0.010 | 0.015 | −0.007 | 0.010 |

| Religious/Spiritual Coping | 0.008 | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.021 | −0.009 | 0.014 |

| Life Satisfaction Baseline | 0.565*** | 0.077 | 0.028 | 0.042 | −0.052 | 0.028 |

| Positive Affect Baseline | −0.010 | 0.102 | 0.468*** | 0.065 | 0.005 | 0.040 |

| Negative Affect Baseline | −0.261 | 0.151 | −0.083 | 0.088 | 0.529*** | 0.065 |

| Spiritual Experiences Baseline (S) | 0.015 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| Gender (G) | −0.056 | 0.075 | 0.010 | 0.043 | 0.001 | 0.029 |

| X × S | −0.041* | 0.018 | −0.025 | 0.015 | −0.013 | 0.018 |

| X × G | 0.107 | 0.068 | −0.054 | 0.058 | −0.075 | 0.058 |

| S × G | −0.026 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| X × S × G | −0.012 | 0.018 | −0.038* | 0.015 | −0.014 | 0.018 |

| Intercept | 8.091*** | 0.736 | 3.896*** | 0.472 | 1.823*** | 0.281 |

| R2 | .351 | .354 | .382 | |||

| F(12, 274) | 12.476*** | 12.522*** | 14.114*** | |||

Note. SE = standard error; X = outcome variable measured at baseline. N = 288.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. (2-tailed).

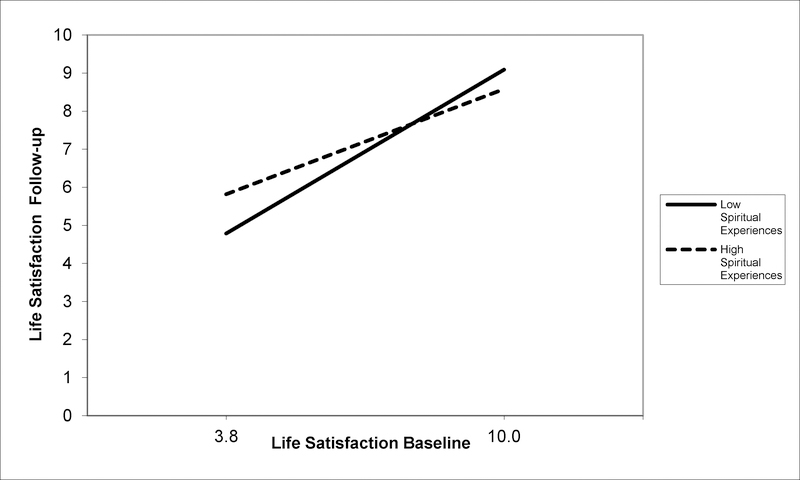

Life Satisfaction

As expected, life satisfaction at baseline predicted life satisfaction ten years later. However, daily spiritual experiences at baseline did not predict life satisfaction at follow-up. In line with our hypothesis, the interaction effect between life satisfaction and spiritual experiences was statistically significant, indicating that change in life satisfaction between baseline and follow-up was moderated by the level of spiritual experiences. Figure 1 illustrates this interaction for low spiritual experiences, defined as the mean minus 1 SD (i.e., −3.03), and high spiritual experiences, defined as the mean plus 1 SD (i.e., 3.03). The x-axis represents the current range of life satisfaction at baseline and the y-axis the life satisfaction at follow-up. Simple slope analysis revealed that the effects of life satisfaction at baseline on life satisfaction at follow-up were positive and significant for both men and women and for low and high spiritual experiences. The strongest effect occurred for women reporting low spiritual experiences (b = 0.83) and the weakest effect occurred for men reporting high spiritual experiences (b = 0.37). Educational attainment, a control variable, contributed to the model such that a higher level of completed education was associated with greater life satisfaction at follow-up. The total explained variance was 35% and the variance explained by the interaction effects above and beyond the simple effects was 2.8%, F(4, 274) = 2.935, p = .021.

Figure 1.

Regression lines of the cancer survivors showing the moderating effect of spiritual experiences for life satisfaction at baseline and follow-up

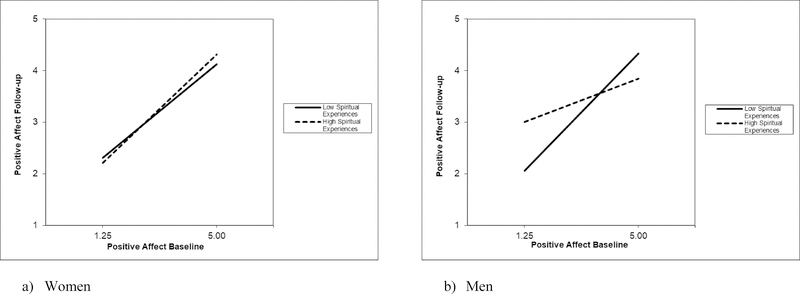

Positive Affect

Positive affect at baseline was a significant predictor of positive affect ten years later, and spiritual experiences at baseline did not predict positive affect at follow-up. The interaction effect between positive affect, spiritual experiences, and gender emerged as significant, indicating that the change of positive affect between baseline and follow-up was moderated by the level of spiritual experiences and that this moderating effect was significantly different between women and men. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between positive affect at baseline and follow-up for low spiritual experiences, defined as the mean minus 1 SD (i.e., −3.03), and high spiritual experiences, defined as the mean plus 1 SD (i.e., 3.03). The effects of positive affect at baseline on positive affect at follow-up were positive and significant with the exception of the effect for women reporting high spiritual experiences, which was not significant (b = 0.22, p = 112). The strongest effect occurred for women reporting low spiritual experiences (b = 0.61). The control variable age was statistically significant, revealing that the younger the individual the higher the positive affect at follow-up. The total explained variance was 35% and the variance explained by the interaction effects above and beyond the simple effects was 2.1%, F(4, 274) = 2.247, p = .064. Although the incremental variance explained by the interaction effects was substantial, it was not significant, suggesting that the sample size was too small.

Figure 2.

Regression lines of the cancer survivors showing the moderating effect of spiritual experiences and gender on positive affect at baseline and follow-up

Negative Affect

In line with the findings for life satisfaction and positive affect, negative affect at baseline was a positive and significant predictor for negative affect at follow up and spiritual experiences at baseline did not predict negative affect at follow-up. Moreover, none of the interaction effects was significant indicating that neither spiritual experiences nor gender had a moderating influence on negative affect over time. The total explained variance was 38%, and the variance explained by the interaction effects above and beyond the simple effects was 0.4%, F(4, 274) = 0.481, p = .750.

Discussion

Cancer survivors face many challenges, including coping with the diagnosis, dealing with side effects of the treatment, or transitioning back to life after treatment, and are therefore vulnerable to low subjective well-being. Underwood and Teresi (2002) posit that daily spiritual experiences, such as inner peace, harmony, and appreciation, may provide a resource for dealing with various forms of illnesses. The present study builds on this notion and examined the influence by which daily spiritual experiences contribute to the enhancement of subjective well-being over time in cancer survivors. We found that daily spiritual experiences alone did not have an effect on subjective well-being approximately 10 years later in cancer survivors, but that these experiences have a moderating effect on life satisfaction and positive affect. Specifically, daily spiritual experiences enhanced life satisfaction over time in women and men with low life satisfaction at baseline. In addition, daily spiritual experiences enhanced positive affect over time in men with low positive affect at baseline. In contrast, daily spiritual experiences did not moderate the effect of negative affect at baseline on negative affect at follow-up.

The current findings extend previous cross-sectional work with adults from the general population (Ellison & Fan, 2008; Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006; Underwood & Teresi, 2002) that suggest that daily spiritual experiences are positively associated with general excitement with life, quality of life, happiness, or positive affect. We found that daily spiritual experiences was associated with greater positive affect over time in men, yet women, on average, reported more daily spiritual experiences than men. This is in line with other studies that found that women have more daily spiritual experiences than men (Kalkstein & Tower, 2009; Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006; Skarupski et al., 2010), whereas men obtain more health benefits than women from religious involvement or church-based support (e.g., Krause, Ellison, & Marcum, 2002; McFarland, 2009). Given this finding, it seems to be crucial for men, especially those reporting low positive affect at baseline, that they get informed by their health professionals about potential ways to elicit daily spiritual experiences in order to strengthen positive affect. Strengthening positive affect may be of particular importance in preventing depression, a common problem in cancer survivors (Osborn, Demoncada, & Feuerstein, 2006). Underwood and Teresi (2002) mention many potential ways to enrich daily spiritual experiences, such as, for instance, choral singing, hiking in nature, natural views from hospital rooms, and private reading, any of which may help cancer survivors at different stages. However, our study did not find evidence that daily spiritual experiences have a positive effect on negative affect over time, which corroborates findings of Underwood and Teresi (2002). That is, a high level of negative affect cannot be reduced by daily spiritual experiences.

The current study has several strengths. One is that this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study examining the role of daily spiritual experiences on subjective well-being in cancer survivors over time. Another one is the large sample size of 288 cancer survivors from a nationally representative U.S. sample. There are also some limitations that may prompt future research. First, our sample consisted of individuals with different types of cancer and specific information about the cancer trajectory were not available. It may be that the moderating effect of daily spiritual experiences is not equally beneficial for all types of cancer and that it interferes with the stage of the cancer ranging from the diagnosis until reintegration into the workplace. Second, the scale used to measure daily spiritual experiences excluded reference to religiosity, which is a strength as it does not exclude people with spiritual experiences not related to Judeo-Christian religion. However, the use of this adapted version limits the comparison with other studies that used the original Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (Fetzer Institute, 1999; Underwood, 2006; Underwood & Teresi, 2002) because the modified version relates to a spiritual experience of being interconnected with all of life, which includes appreciation, gratitude, and caring for others. Third, all information was based on self-report and the cancer survivors participated voluntary, so biases in response and selection might be possible. Fourth, our sample consisted of predominantly White people. In future studies it would be interesting to examine the role of daily spiritual experiences in cancer survivors from diverse races. For instance, there is evidence that older Black people are more likely to experience health-related benefits of religion than older White people do (Krause, 2002).

In summary, our results showed that daily spiritual experiences moderated the change in life satisfaction in both women and men and in positive affect in men. It is hoped that many cancer survivors, especially those with low life satisfaction and men with low positive affect, get informed about possibilities to foster daily spiritual experiences and that further research will examine its effect and explore creative ways to enhance daily spiritual experiences in cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported through support from the National Institute on Aging (1U19AG051426-01).

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Haffer SC, & Denniston M (2003). Health-related quality of life of cancer and noncancer patients in medicare managed care. Cancer, 97, 674–681. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, & Lucas RE (2000). Subjective emotional well-being In Lewis M & Haviland JM (Eds.). Handbook of Emotions (pp. 325–370). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Tay L, & Myers DG (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1278–1290. doi: 10.1037/a0024402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, Peasgood T, & White M (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32, 80–99. doi: 10.2307/2136801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Fan D (2008). Daily spiritual experiences and psychological well-being among us adults. Social Indicators Research, 88, 247–271. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9187-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erdfelder E, Faul F, & Buchner A (1996). GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers, 28, 1–11. doi: 10.3758/BF03203630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL, & Cornblat MW (2002). Breast cancer survivors give voice: A qualitative analysis of spiritual factors in long-term adjustment. Psycho-Oncology, 11, 524–535. doi: 10.1002/pon.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Vaillant GE, & Marks NF (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being?, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196–212. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson PD, Gore SV, Davis BL, & Condon EH (2003). Breast cancer: A qualitative analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, 641–647. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.641-647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Rowland JH, & Yancik R (2003). Cancer survivors in the United States: Age, health, and disability. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 58, 82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.M82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL,Musick M.a, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, … Williams DR (2003). Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research. Research on Aging, 25, 327–365. doi: 10.1177/0164027503252749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkstein S, & Tower RB (2009). The daily spiritual experiences scale and well-being: Demographic comparisons and scale validation with older Jewish adults and a diverse internet sample. Journal of Religion and Health, 48, 402–417. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa S (2015). Where do Gods come from?. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7, 306–313. doi: 10.1037/rel0000033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2002). Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 57B, S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.S332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Ellison CG, & Marcum JP (2002). The effects of church-based emotional support on health: Do they vary by gender?. Sociology of Religion, 63, 21–47. doi: 10.2307/3712538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, & Donnellan MB (2007). How stable is happiness? Using the STARTS model to estimate the stability of life satisfaction. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, & Kubzansky LD (2006). Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 2848–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ (2009). Religion and mental health among older adults: Do the effects of religious involvement vary by gender?. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65, 621–630. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA (2006). Exploring the dimensionality of “religiosity” and “spirituality” in the Fetzer Multidimensional Measure. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 449–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00318.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, & Feuerstein M (2006). Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 36, 13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Edmondson D, Hale-Smith A, & Blank TO (2009). Religiousness/spirituality and health behaviors in younger adult cancer survivors: Does faith promote a healthier lifestyle? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 582–591. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9223-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenda KM, & Lachman ME (2001). Planning for the future: A life management strategy for increasing control and life satisfaction in adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 16, 206–216. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin C, Rogers ML, Pinto BM, Nash JM, Frierson GM, & Trask PC (2007). Effect of personal cancer history and family cancer history on levels of psychological distress. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler BT, & Ryff CD (2010). Who participates? Accounting or longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 307–331. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz M, Mao MS, Omlin A, Bueche D, Cerny T, & Strasser F (2015). Spiritual experiences of transcendence in patients with advanced cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 32, 178–188. doi: 10.1177/1049909113512201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A Review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, Almeida DM, Ayanian JS, Carr DS, Cleary PD, Coe C, . . . Williams D (2018, November 15). National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II), 2004–2006 (ICPSR04652-v6). Ann Arbor, MI: Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. Retrieved from ; 10.3886/ICPSR04652.v7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JA, & Brockopp DY (2012). Twenty-five years later—what do we know about religion/spirituality and psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors? A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 6, 82–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz DCM, Hagmann D, Besier T, Dieluweit U, Debatin KM, Grabow D, … Goldbeck L (2011). Life satisfaction in adult survivors of cancer during adolescence: What contributes to the latter satisfaction with life? Quality of Life Research, 20, 225–236. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9739-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CE, Crowther M, & Higgerson HK (2007). The stage-specific role of spirituality among African American Christian women throughout the breast cancer experience. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 26–34. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarupski KA, Fitchett G, Evans DA, Mendes CF, & Leon D (2010). Daily spiritual experiences in a biracial, community-based population of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 14, 779–789. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanek M, McDonald PG, & Hess SA (2005). Religion, spirituality and cancer: Current status and methodological challenges. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 450–463. doi: 10.1002/pon.861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuné-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, & Newman SP (2006). Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG (2006). Ordinary spiritual experience: Qualitative research, interpretive guidelines, and population distribution for the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale. Archive for the Psychology of Religion/Archiv für Religionspsychologie, 28, 181–218. doi: 10.1163/008467206777832562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood LG, & Teresi JA (2002). The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Walker LM (1996). The long-term stability and predictive validity of trait measures of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 567–577. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]