Abstract

Introduction

Psychological factors such as fear avoidance beliefs, depression, anxiety, catastrophic thinking and familial and social stress, have been associated with high disability levels in people with chronic low back pain (LBP). Guidelines endorse the integration of psychological interventions in the management of chronic LBP. However, uncertainty surrounds the comparative effectiveness of different psychological approaches. Network meta-analysis (NMA) allows comparison and ranking of numerous competing interventions for a given outcome of interest. Therefore, we will perform a systematic review with a NMA to determine which type of psychological intervention is most effective for adults with chronic non-specific LBP.

Methods and analysis

We will search electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, SCOPUS and CINAHL) from inception until 22 August 2019 for randomised controlled trials comparing psychological interventions to any comparison interventions in adults with chronic non-specific LBP. There will be no restriction on language. The primary outcomes will include physical function and pain intensity, and secondary outcomes will include health-related quality of life, fear avoidance, intervention compliance and safety. Risk of bias will be assessed using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) tool and confidence in the evidence will be assessed using the Confidence in NMA (CINeMA) framework. We will conduct a random-effects NMA using a frequentist approach to estimate relative effects for all comparisons between treatments and rank treatments according to the mean rank and surface under the cumulative ranking curve values. All analyses will be performed in Stata.

Ethics and dissemination

No ethical approval is required. The research will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019138074.

Keywords: back pain, musculoskeletal disorders, psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review using an network meta-analysis (NMA) design to simultaneously compare different types of psychological interventions for improving physical function, pain intensity, health-related quality of life, fear avoidance and intervention compliance and assess their safety, in people with chronic non-specific low back pain.

The main strength is the NMA design will allow for the comprehensive comparison and ranking of multiple psychological interventions simultaneously, which was not possible with previous systematic reviews that only conducted pairwise meta-analyses.

An additional strength is that in comparison to previous pairwise systematic reviews, the NMA design will allow for the inclusion and synthesis of a larger number of studies investigating a wider range of psychological interventions.

The main limitation is that we anticipate numerous studies involving different combinations of psychological approaches (eg, cognitive behavioural therapy plus pain education, counselling-based interventions plus pain education), but small number of eligible studies per combination, hence we will lump combination interventions into one treatment node for practical reasons.

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the largest contributors to disability worldwide1 2 and is associated with substantial health and economic burden relating to increased healthcare utilisation costs, work absenteeism and productivity loss.3 The challenge associated with treating chronic non-specific LBP lies in the complex multifactorial interaction between genetic, biophysical, psychosocial, health and lifestyle factors which are largely individualistic.4 5 Particularly, psychological factors such as fear avoidance beliefs, depression, anxiety, catastrophic thinking and familial and social stress4 are often poorly identified and inadequately addressed,6 and have been shown to alter pain processing pathways, perceptions and coping responses.5 7 The influence of these factors in chronic non-specific LBP have been found to increase the risk of disability,8 9 which commonly manifests as reduced functional capacity, avoidance of usual activities including work and impaired societal and recreational participation.5 10

Psychological interventions in chronic pain conditions aim to reduce pain-related distress and disability by changing negative beliefs, behaviours and attitudes through a combination of principles and strategies informed by psychological theories. Psychological interventions commonly focus on targeting the specific environmental contingencies and maladaptive cognitive and emotional processes underpinning pain in order to promote self-efficacy and increased function.11 12 In clinical trials of psychological interventions for chronic LBP, psychological interventions are delivered either in isolation12 13 or as part of an integrated treatment programme that may involve non-psychological co-interventions such as exercise, passive treatment or physiotherapy.14–16 For the purposes of this review, we have defined five main categories of psychological interventions relevant to LBP: behavioural therapy-based interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy-based interventions, mindfulness-based interventions, counselling-based interventions and pain education-based interventions. These categories reflect the three ‘waves’ of how psychological interventions have evolved over time.17 Behavioural interventions are typically considered ‘first wave’ approaches,17 and include interventions focussed on altering maladaptive behaviours, and dysfunctional sensations or movements.18 Cognitive behavioural interventions are considered ‘second wave’ approaches,17 and include interventions that aim to modify harmful cognitions (eg, thoughts, beliefs) which may proliferate pain and disability.18 Mindfulness-based interventions, counselling-based interventions and pain education-based interventions represent different types of ‘third wave’ approaches.17 Unlike behavioural and cognitive behavioural interventions which focus on targeting psychological and emotional symptoms, ‘third wave’ interventions adopt a more holistic approach to promoting health and wellness.17 Key characteristics and examples of the psychological intervention categories that will be included in our review are summarised below in table 1.

Table 1.

Categories of psychological interventions for low back pain

| Category | Characteristics | Examples | |

| First wave | Behavioural therapy-based interventions | Behavioural interventions focus on the removal of positive reinforcement of pain behaviours and teach patients to overcome stressful situations through relaxation skills.17 | Biofeedback(17 18) |

| Second wave | Cognitive behavioural therapy-based interventions | Cognitive behavioural interventions aim to restructure negative cognitions (eg, thoughts, beliefs) and behaviours and promote emotion regulation and problem-solving capacity.17 | Graded activity(17) Graded exposure(17) |

| Third wave | Mindfulness-based interventions | Mindfulness-based interventions focus on promoting self-awareness, attention control and pain acceptance.13 52 | Mindfulness-based stress reduction(17 52) Acceptance and commitment therapy(17) |

| Counselling-based interventions | Counselling-based interventions focus on using supportive communication and active listening techniques to build interpersonal clinician-patient relationships. | Health coaching(54 55) Motivational interviewing(54 55) |

|

| Pain education-based interventions | Pain education-based interventions target a patient’s understanding and knowledge of pain to reduce fear associated with low back pain. Pain education interventions move away from the traditional biomechanical explanation of pathology and pain, and instead focus on the reconceptualisation of the pain experience. Some pain education interventions specifically aim to desensitise the nervous system. | Pain neuroscience education(82) |

Previous systematic reviews have shown promising evidence that psychological interventions can improve overall functioning, pain experience, depression, cognitive appraisal, health-related quality of life and decreased healthcare utilisation in people with chronic LBP.11 12 15 Psychological interventions can also reduce fear avoidance beliefs and behaviours (eg, kinesiophobia),19 which are associated with increased disability and pain in people with chronic LBP.20 21 Based on the evidence and LBP research experts, international clinical guidelines consistently endorse the integration of psychological interventions with exercise in the management of chronic LBP.22–27

However, LBP guideline recommendations remain vague regarding the specific types of psychological approaches that clinicians should consider incorporating into treatment.22–27 This may be due to the fact that previous systematic reviews, which have informed these guidelines, have mainly focussed on a small selection of available approaches—namely cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural approaches such as biofeedback.11 12 15 18 28 29 Emerging psychological interventions such as cognitive functional therapy (a combination of psychological approaches involving cognitive behavioural strategies, pain education and exercise)5 and acceptance and commitment therapy have been neglected from these reviews, despite recent evidence for their effectiveness in reducing LBP-related disability.30 31 Importantly, previous reviews have only conducted multiple independent pairwise meta-analyses, and to our knowledge, no attempts have been made to synthesise the separate results. Ultimately, the comparative effectiveness of the wider collection of psychological interventions available for managing chronic LBP is unknown and clinical guidelines remain unclear. This represents an important gap in the evidence. Subsequently, there is an increased reliance on a clinician’s expertise to select the most appropriate psychological approach for people with chronic LBP. Given that clinicians such as physiotherapists report a perceived lack of training and confidence in addressing psychological factors,32–34 and tend to be biassed towards a biomedical approach despite increasing efforts to adopt a biopsychosocial, person-centred approach,34 35 the gap in evidence must be addressed. A network meta-analysis (NMA) design will allow us to determine the comparative effectiveness of psychological interventions for managing chronic LBP, while addressing the limitations identified from previous reviews.

A NMA is an extension of a traditional pairwise meta-analysis and involves the synthesis of direct and indirect evidence to simultaneously compare numerous competing interventions within a single, coherent treatment network.36 Direct evidence refers to data obtained from studies directly comparing competing interventions in head-to-head trials. Direct evidence can be used to indirectly estimate the effect of interventions that have not been previously compared in head-to-head trials but have been compared with a common comparator (indirect evidence). Integrating direct and indirect evidence increases the precision of treatment effect estimates, provided that the assumptions of transitivity (balanced distribution of potential effect modifiers across all comparisons within a network)37–39 and consistency (statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for each comparison)39 40 are satisfied. Treatment effect estimates are used to generate relative treatment rankings to rank all the competing interventions for a particular outcome measure. As such, the current research aims to perform a NMA to investigate the comparative effectiveness and safety of psychological interventions for chronic LBP and determine which specific type is most effective for improving physical function, pain intensity, health-related quality of life, fear avoidance and intervention compliance in chronic non-specific LBP.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This protocol was written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement for systematic reviews41 and the PRISMA extension for developing review protocols (PRISMA-P)42 and for NMA (PRISMA-NMA).43 The systematic review protocol has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42019138074.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

We will include published parallel and cluster randomised controlled trials (RCT). We will also include the first phase of cross-over RCTs. There will be no restriction on length of follow-up. Observational studies, non-randomised trials, short reports, research letters, conferences abstracts or studies that have not been published as full-length articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals will be excluded. In accordance with the Cochrane handbook,44 we will only include data from cluster RCTs which account for the cluster design (eg, data analysed at the level of allocation). If cluster-level data is not reported for a given cluster RCT study, we will attempt to use the approximate approaches described in the Cochrane handbook to adjust the results,44 otherwise the study will be excluded.

Types of participants

Eligible studies will include adults experiencing chronic non-specific LBP, with or without the presence of leg pain. Chronic non-specific LBP will be defined according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) UK guidelines as pain in the back between the bottom of the rib cage and buttocks crease with no known pathoanatomical cause, for greater than 12 weeks in duration.22 45 Studies including participants with serious pathologies (eg, spinal stenosis, malignancy, trauma, vertebral fracture, infection, inflammatory disorders) will be excluded. We will include studies involving a combination of acute, subacute or chronic LBP populations, provided that >50% of participants have chronic LBP and the results are reported separately for chronic LBP populations. We will also include studies of chronic LBP participants combined with other chronic pain conditions, provided that >50% of participants have a single diagnosis of chronic LBP and the results are reported separately for chronic LBP populations. If it is unclear, study eligibility will be determined by consensus among reviewers.

Types of interventions

We will include studies of psychological interventions. Expanding on the definition provided by Hoffman et al,12 we will consider an intervention as ‘psychological’ if it is conceived by the authors of the study as a psychological intervention, or if it is clearly based on any of the following approaches: cognitive behavioural therapeutic strategies (relaxation, graded exposure (desensitisation), imagery (distraction), goal setting, operant conditioning), mindfulness-based stress reduction, acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive functional therapy, health-coaching, biofeedback (delivered with a therapeutic intent to promote muscle relaxation), pain education and counselling directly employing principles of psychological theory. Interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapeutic strategies and biofeedback were purposely included based on their inclusion across a variety of previous relevant systematic reviews.12 15 17 18 Additional approaches such as cognitive functional therapy, health coaching and acceptance and commitment therapy were included as they have been neglected in previous reviews. If our search identifies other psychological interventions which are not explicitly listed above but meet our definition for a psychological intervention, we will consider including them in our review. Disagreements regarding their eligibility for inclusion will be resolved by consensus.

We will include studies of combinations of psychological interventions, defined as interventions that contain two or more psychological approaches delivered together, with or without additional non-psychological co-interventions. There will be no restriction on the non-psychological co-interventions or comparison interventions identified by our search strategy.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest are physical function and pain intensity:

Physical function, defined as lower back specific physical function, measured at the end of treatment. Physical function is commonly measured by continuous, self-report scales (eg, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI), Quebec Back Pain Disability Index (QBPDI)) or rating scales within a composite measure (eg, 12-Item or 36-Item Short Form (SF-12, SF-36)). We will not exclude studies that use other measurement tools.

Pain intensity, measured at the time point closest to the end of treatment. Pain intensity is commonly measured by continuous, self-report scales (eg, Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)) or a rating scale within a composite rating scale (eg, McGill Pain Questionnaire). We will not exclude studies that use other measurement tools.

Secondary outcomes of interest include:

Health-related quality of life, measured at the end of treatment. It is commonly measured by the SF-12, SF-36, EuroQol five-dimension (EQ-5D), Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) and 10-Item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health Short Form (PROMIS-GH-10). We will not exclude studies that use other measurement tools.

Fear avoidance, defined as fear of pain and consequent avoidance of movement, measured at the end of treatment. Fear avoidance is commonly measured by the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ), Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) and Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FPQ). We will not exclude studies that use other measurement tools.

Intervention compliance, measured as the proportion of participants who complete their assigned intervention (psychological or comparison) during the intervention period.

Safety, defined as the proportion of participants who experience at least one adverse effect during the intervention period. Adverse effects will be broadly defined as any ‘adverse event,’ ‘side effect,’ ‘complication’ or event resulting in discontinuation of treatment, associated with the intervention (psychological or comparison) under investigation.

Study selection

Electronic searches

The following databases will be searched for eligible studies via Ovid from inception until 22 August 2019: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, SCOPUS and CINAHL. Search concepts will include language and keywords for: randomised controlled trial, low back pain and terms relating to psychological interventions, according to the eligibility criteria defined earlier in the protocol. A full MEDLINE search strategy can be found in online supplementary appendix A of this protocol. There will be no restriction on language.

bmjopen-2019-034996supp001.pdf (99.8KB, pdf)

Additional search strategies

We will search reference lists and perform citation tracking of included studies and relevant systematic reviews11 12 15 17 18 28 29 and clinical guidelines22–24 to identify additional eligible studies.

Identification and selection of studies

Citations identified by our search strategy will be managed using EndNote X946 and screened using Covidence.47 Eligibility screening will be conducted independently by two reviewers in two independent stages: (1) citation titles and abstracts and (2) full text. Disagreements will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer. A PRISMA flow-diagram will be presented to map the number of records included and excluded during the study selection process, with reasons for exclusions reported.

Data extraction

Two reviewers will independently extract data from the included studies using a pre-designed Microsoft Excel data extraction form. We will pilot-test the form on a small number of articles. Disagreements will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer.

Publication characteristics

We will extract data on the following publication characteristics: first author, publication year, journal, funding and location.

Study design characteristics

We will extract data related to the study design, including number of participants randomised and durations of follow-up.

Participant characteristics

We will extract data on the individual study sample, including age, male/female, body mass index, baseline pain intensity, socioeconomic status and comorbidities.

Interventions and comparators

We will extract data on the interventions of interest and any comparation interventions. We will extract the key components of the psychological intervention (eg, details of the specific psychological principles or approaches used, qualifications of the personnel delivering the intervention, co-interventions involved) and comparison intervention. We will extract all available data on intervention dosage and frequency, and intervention duration including duration of any washout.

Outcomes

We will extract the definitions provided for our primary and secondary outcomes of interest. We will also extract the type and dimensions of the measurement tools used to assess our primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Results

For intervention compliance, we will extract the number of participants randomised to each intervention group (psychological or comparison), as well as the number of participants who complete their assigned intervention (ie, provide data at the time point closest to the end of treatment). If this data is not available, we will extract the number of participants in each group who discontinued treatment for any reason (ie, all-cause discontinuation) within the intervention period, to calculate the number of participants who completed their assigned intervention. We will express this data as a proportion of the total number of participants randomised to each group respectively. For studies comparing a psychological intervention to a non-intervention comparison (ie, waitlist control, no intervention), we will assume that the intervention compliance for the non-intervention comparison is 100%.

For safety, we will extract all available data on adverse effects, broadly encompassing adverse and serious adverse events, side effects, complications and all-cause discontinuation. We will extract authors’ definitions and reasons for any adverse effects. We will also extract all available data, including authors’ definitions, on alternative measures of safety reported in the included studies. We will extract the number of participants who experience at least one adverse effect related to the psychological or comparison intervention under investigation and express this as a proportion of the total number of participants randomised to each group respectively. We will also extract data on adherence if reported.

For all other outcome measures, we will be preference extracting the mean baseline and outcome scores (at the time point closest to end of treatment) for each group, and the accompanying measures of variance or statistics to impute these values. Otherwise, we will extract the change in outcome from baseline and the accompanying measures of variance for each group. If neither are available, we will extract between-group differences in scores and the accompanying measures of variance. For the following outcomes, we will extract all available data in the order which the measurement tools are listed, in accordance with the proposed hierarchy for analysis. If a given outcome is measured by several measurement tools not explicitly listed, the hierarchy for analysis will be decided by consensus from the reviewers.

For studies measuring physical function: ODI; RMDQ; COMI; QBPQI; rating scale for disability from a composite measure of physical function (eg, SF-12, SF-36); other measurement tools.48 49 For studies measuring pain intensity: NRS; 100 mm VAS; 10 cm VAS; rating scale for pain intensity from a composite measure of pain intensity; other measurement tools.48 49 We will extract data on pain intensity at the time point closest to randomisation and end of treatment, in the order of average pain intensity (preferred); worst pain intensity, alternative measures of pain intensity. If several alternative measures of pain intensity are reported, we will calculate an average score. For studies measuring health-related quality of life: PROMIS-GH-10; EQ-5D; SF-36 or SF-12 (physical component summary subscore); SF-36 or SF-12 (mental component summary subscore); SF-36 (overall score); NHP;48 49 rating scale from a composite measure of health-related quality of life; other measurement tools. If only an overall score for the SF-36 is provided, we will contact authors for the physical and mental component summary subscores. For studies measuring fear avoidance: FABQ (physical activity scale); FABQ (work scale); FABQ (overall score); PCS, TSK; FPQ; rating scales of fear avoidance from a composite measure of fear avoidance; other measurement tools.50 If only an overall score for the FABQ is provided, we will contact authors for the physical activity and work subscores. Authors will be contacted for additional information where necessary.

Data will be classified and assessed at the following time points: (1) pre-intervention; (2) post-intervention (ie, time point closest to end of treatment); (3) short-term treatment sustainability (≥2 months but <6 months post-intervention); (4) mid-term treatment sustainability (≥6 months but <12 months post-intervention); (5) long-term treatment sustainability (≥12 months post-intervention), and NMA will be performed at each time point separately.

Network treatment nodes

Using the framework proposed by Caldwell et al,51 we will use a splitting approach to classify the psychological interventions. A splitting approach was chosen because psychological interventions are typically complex and heterogeneous in nature. For example, two separate trials involving cognitive behavioural therapy may focus on using different psychological principles or strategies and incorporate different additional co-interventions (eg, exercise, passive therapies). Failing to adequately account for the variability, as best as possible, may potentially result in inaccurate estimates of treatment effects. In attempts to account for heterogeneity, we will first scrutinise intervention descriptions to classify the psychological interventions into five treatment nodes based on five key approaches (behavioural, cognitive behavioural, mindfulness-based, counselling-based and pain education). We will also form a separate treatment node using a lumping method to account for combination approaches (eg, two or more psychological approaches delivered together). Then, we will further differentiate whether additional non-psychological co-interventions are involved, which will be subclassified as exercise, passive treatments or physiotherapy. If present, the combination of the psychological approach with a non-psychological co-intervention will form a separate treatment node (eg, cognitive behavioural therapy plus exercise).

The following treatment nodes will be formed for the psychological interventions:

Behavioural therapy-based interventions (eg, relaxation-based interventions, biofeedback, operant conditioning), which we will consider as psychological approaches focussed on facilitating the removal of positive reinforcement of pain behaviours and promoting health behaviours, in the absence of cognitive strategies;17 18

Cognitive behavioural therapy-based interventions, which we will consider as the combination of behavioural therapies with an additional focus of changing unhelpful cognitions (ie, thoughts, beliefs and attitudes), and/or promoting emotion regulation and problem-solving;17

Mindfulness-based interventions, which we will consider as psychological approaches focussed on practicing techniques such as meditation, non-judgemental attention control and awareness (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction, acceptance and commitment therapy);52 53

Counselling-based interventions, which we will consider as psychological approaches focussed on using supportive communication and active listening techniques to facilitate healthy behaviour change (eg, health coaching, motivational interviewing);54 55

Pain education-based interventions, which we will consider as psychological approaches focussed on improving understanding and knowledge about pain. These interventions may involve a biomechanical explanation of LBP, but are clearly focussed on the reconceptualisation of beliefs about the pain experience;56

Combinations of psychological interventions (eg, pain education combined with behavioural therapy), which we will consider as the delivery of two or more psychological approaches together, in the absence of a non-psychological co-intervention.

Non-psychological co-interventions will be classified into the following treatment nodes:

Exercise, which we will define as interventions that formally prescribe a structured exercise programme (eg, consisting of aerobic, strengthening, stretching, stabilisation, motor control exercises) and/or direct instructions to increase physical activity levels;

Passive treatment, including but not limited to spinal manipulative therapy, massage and electrotherapies;

Physiotherapy, which we will define as interventions delivered by a physiotherapist, which may involve a combination of exercise and passive treatments.

Comparison interventions will be classified into the following treatment nodes:

Exercise, defined above;

Passive treatment, defined above;

Physiotherapy, defined above;

General practitioner care, which we will define as interventions considered as standard care provided by general practitioners;

Advice, which we will consider as interventions providing general advice that is not psychologically-informed;

No intervention (eg, waitlist control, no intervention).

For comparison interventions described as ‘usual care’ by study authors, we will scrutinise the authors’ descriptions of the intervention to classify them into the above treatment nodes.

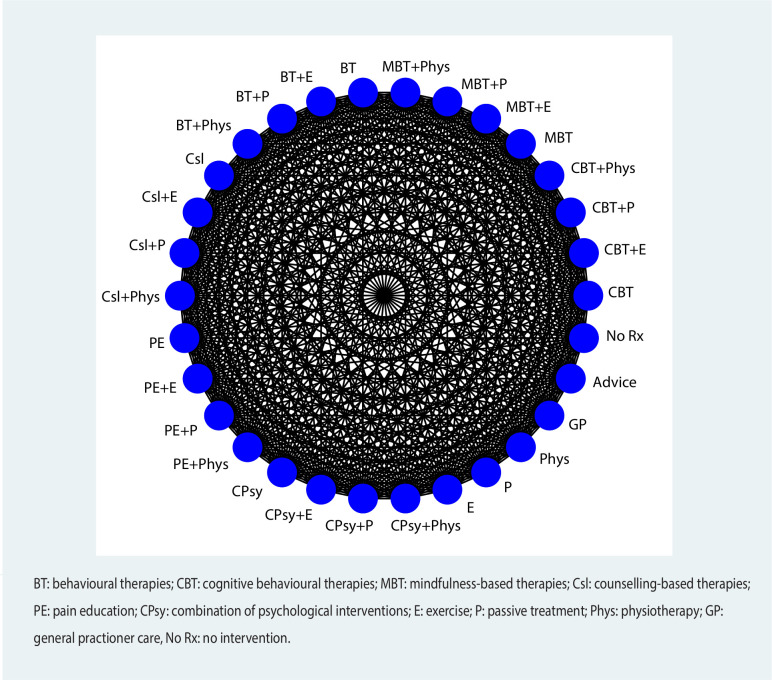

Figure 1 represents all possible combinations of treatment nodes. Consensus will be sought regarding accurate classification of interventions prior to conducting statistical analyses.

Figure 1.

Network plot of all theoretically possible network comparisons.

Prior to data analysis, we will consult clinical experts from the review team to establish the appropriateness of further lumping treatment nodes together if there are inadequate number of studies are available for a given treatment node (eg, less than two studies available). Any post-hoc alternative network geometrics formed using this approach will be clearly identified and justified in the final review. A decision set and supplementary set will be formulated for the final review.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Two reviewers will independently assess risk of bias in the included studies using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2).57 58 We will use the licensed Microsoft Excel tool to implement the RoB 2. We will pilot-test the risk of bias assessment procedure on a small number of articles. Authors will be contacted for additional information where necessary. The RoB 2 assesses five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomisation process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in measurement of the outcome; and (5) bias in selection of the reported result. Each domain will be graded as low risk of bias, some concerns or high risk of bias, and the results will be summarised in a table. For cluster RCTs, we will use the Cochrane cluster RCT variant of the RoB 2 tool, which assesses an additional domain: bias arising from identification or recruitment of individual participants within clusters.59 An overall risk of bias judgement (low risk of bias, some concerns, or high risk of bias) will be made based on the five (or six) domain-level judgements, as described in Sterne et al.57 Generally, the overall risk of bias judgement corresponds to the worst risk of bias in any of the five (or six) domains, however studies with multiple domains graded as ‘some concerns’ may be judged as high risk of overall bias.57 Disagreements will be resolved through consensus or a third reviewer.

Data analysis

Characteristics of the publications, study designs, study populations, interventions and comparators and outcome measures will be summarised descriptively and presented in a table. Pairwise meta-analysis and NMA will be performed in Stata60 using the metan command (with Knapp-Hartung adjustment applied), and the network package61–63 and network graphs package,64 65 respectively.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes that use the same rating scale across all studies, we will use mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs. If different rating scales are used for comparable outcomes, all continuous data for the given outcome will be converted to a common standardised 0 to 100 scale. If data is reported as dichotomous, we will use ORs and 95% CI.

Dealing with missing outcome data and missing statistics

For continuous outcomes, we will impute missing data by converting standard errors, p values or CI into SD.44 If a study only reports the median or IQR, SD will be calculated by dividing the IQR by 1.35, and we will consider the median to be equivalent to the mean. If relevant information is provided in figures, we will extract data from the graphs. If data cannot be obtained, we will attempt to contact authors.

Geometry of the network

The network diagram will be used to graphically depict the available evidence. Nodes will be used to represent the different interventions and comparators, and the weight of the edges will be used to visually represent the proportional number of studies comparing two connected nodes within the network.

Pairwise meta-analysis

We will perform traditional pairwise meta-analyses of all direct comparisons for which there are at least two studies available. We will apply the khartung command to adjust for the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman random-effects method, which has less error rates compared with the DerSimonian and Laird approach in particular across comparisons with greater heterogeneity and when the number of studies is small.66 We will assume the heterogeneity variance for each pairwise comparison is different. We will use the Q statistic to test for statistical heterogeneity in pairwise comparisons. We will use alpha <0.10 as we anticipate a few studies per comparison. We will calculate Higgins I2 statistic to indicate the proportion of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity and interpret I2 >50% as suggesting substantial heterogeneity.44 Forest plots will be created to graphically depict individual and pooled effect sizes. Narrative analysis will be performed if we are unable to impute missing data or cannot contact authors for data, inadequate number of studies are available for a given comparison (eg, <2 studies), or there is substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of transitivity assumption

Transitivity implies the assumption that distribution of clinical and methodological variables that could potentially act as effect modifiers across available treatment comparisons is balanced within a network.37–39 67 Given the lack of conclusive evidence on treatment effect modifiers for LBP68 or psychological interventions,12 69 70 we will consider the following factors to be potential effect modifiers: age,68 gender,71 sample size,72 baseline physical function, baseline pain intensity, baseline fear avoidance,73 sciatica (leg pain with nerve root compromise). We anticipate that we will have difficulty assessing the distribution of effect modifiers, due to insufficient reporting the potential effect modifiers within individual studies and few studies available per pairwise comparison to make reasonable judgements.74 To assess transitivity, we will use Stata to adjust the weight of the edges within the network plot, proportional to the baseline distribution of the pre-specified effect modifier and visually inspect comparability within the network.67 If minor intransitivity is suspected (ie, minor or negligible dissimilarities in the distribution of a given effect modifier across comparisons based on clinical judgement), we will proceed with the NMA and perform network meta-regressions or subgroup analyses (or both) to explore the influence of suspected factors on the results. If the distribution of a given effect modifier is clearly dissimilar across comparisons, we will exclude network nodes. If intransitivity persists, we will consider not proceeding with NMA.

Network meta-analysis

A NMA will be performed using a frequentist approach to simultaneously compare direct and indirect evidence. We will assume the heterogeneity variance across different comparisons within the NMA model will be the same.75 We will use heterogeneity variances from the NMA model as an index of global network heterogeneity. Mean rank and relative treatment rankings will be estimated for each intervention node according to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) values.

Assessment of inconsistency

Valid NMA results rely on the assumption of consistency, which describes statistical agreement between direct and indirect evidence for each comparison within a network.39 40 Global inconsistency of the entire network will be assessed using the design-by-treatment interaction model,76 which is a goodness-of-fit test. The presence of inconsistency will be inferred based on p<0.10. Local inconsistencies within closed loops will be assessed with the loop specific approach (Bucher method),77 and by fitting side-splitting models.61 The loop specific approach (Bucher method) will be implemented in Stata using the ifplot command. We will infer the presence of local inconsistencies using a threshold of p<0.10 for either approach. If inconsistencies are identified, we will first check for errors in data extraction. Then, we will examine the potential influence of the pre-specified effect modifiers within inconsistent loops using network meta-regression models or subgroup analyses, and conduct sensitivity analyses excluding studies that may be the source of inconsistency (eg, high risk of bias, studies measuring physical function using the SF-12 or SF-36). If substantial inconsistency remains and the origin remains unexplained, we will consider not proceeding with NMA.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

To examine robustness of results, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies with high risk of bias, provided that the original network structure remains the same. We will also perform a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies measuring physical function using the SF-12 or SF-36, which may be a potential source of heterogeneity, provided that sufficient data for physical function is available and the original network structure remains the same. We will also perform network meta-regressions or subgroup analyses on the following covariates, if sufficient data is available: age, gender, sample size, baseline physical function levels, baseline pain levels, baseline fear avoidance, sciatica (leg pain with nerve root compromise). We will assume that for each network meta-regression model, the regression co-efficient for each covariate will be the same across all comparisons in the network. We specify the following assumptions about the direction of effect for each covariate:

Age (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Gender (continuous): Gender will be summarised as the proportion (percentage) of males. Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Sample size (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Baseline physical function (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate increases the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Baseline pain intensity (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Baseline fear avoidance (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Sciatica (leg pain with nerve root compromise)(continuous): Presence of sciatica will be summarised as the proportion (percentage) of participants reporting sciatica at baseline. Increasing magnitudes of the covariate reduces the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

Further, subject to the availability of data, we will attempt to perform meta-regressions to explore the effects of intervention parameters relating to dosage and/or frequency (eg, total length (in weeks) of the intervention, total intended hours of the intervention during the intervention period). We make the following assumption about the direction of effect for intervention dosage and/or frequency (continuous): Increasing magnitudes of the covariate increases the differences in effect sizes between the intervention and comparator (compared with trials in which the covariate is less).

We will also perform the following subgroup analyses, provided that sufficient data is available and the original network structure remains the same:

Delivery format of psychological intervention (eg, face-to-face, telephone-administered, web-based, self-help booklets), the hypothesis is that face-to-face delivery format will result in greater improvements in disability and pain intensity.

Individual versus group-based intervention delivery, the hypothesis is that group-based interventions will result in greater improvements in disability and pain intensity.

Publication bias

Publication bias in the NMA will be evaluated by visual inspection of comparison-adjusted funnel plots for asymmetry. As described above, meta-regression using sample size and effect estimates will be performed to detected small study effect.78

Confidence in cumulative evidence

Judgements of the confidence in cumulative evidence will be evaluated using the Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) framework,79–81 a web application of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation ratings approach. The framework assesses six domains: within-study bias, across-studies bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity and incoherence.

Patient and public involvement

Patients will not be involved.

Contributions to literature

To date, there is no conclusive consensus regarding the most effective psychological approach for managing chronic non-specific LBP. Previous studies have only investigated a small portion of available psychological interventions and have only conducted multiple independent pairwise meta-analyses which have not been synthesised. As such, clinical guidelines for chronic LBP, which are based on these reviews, remain vague regarding the specific type of psychological intervention which should be incorporated into treatment for the condition. This systematic review with NMA will synthesise direct and indirect evidence for a comprehensive variety of psychological interventions with respect to improving physical function, pain intensity, health-related quality of life and fear avoidance in people with chronic non-specific LBP. The review will also assess the proportion of compliance to different psychological interventions in this population, as well as the safety of such interventions. The NMA will compare the competing interventions within the network and produce treatment effect estimates. Effect estimates will be used to generate relative treatment rankings, allowing us to rank the different types of psychological approaches for each outcome. Findings from this review will provide pragmatic support for clinical guideline recommendations regarding the use of psychological interventions for adults with chronic non-specific LBP.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical review will not be required as the systematic review will only involve the use of previously published data for analysis. Our intention is to publish the completed research in a peer-review journal and present our findings at national and international conferences.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors (EKH, MF, LC, MS, CA-J, JC, JAH, PF) conceived the study. EKH drafted the manuscript. EKH, LC and JC participated in the search strategy development. PF assisted in the initial protocol design, and all authors (EKH, MF, LC, MS, CA-J, JC, JAH, PF) assisted in the protocol revision. LC provided statistical expertise. CA provided expertise on psychological interventions. All authors (EKH, MF, LC, MS, CA-J, JC, JAH, PF) read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sebbag E, Felten R, Sagez F, et al. The world-wide burden of musculoskeletal diseases: a systematic analysis of the world Health organization burden of diseases database. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:844–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet 2018;392:1789–858. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J 2008;8:8–20. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018;391:2356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O'Keeffe M, et al. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther 2018;98:408–23. 10.1093/ptj/pzy022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Keeffe M, George SZ, O'Sullivan PB, et al. Psychosocial factors in low back pain: letting go of our misconceptions can help management. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:793–4. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikemoto T, Miki K, Matsubara T, et al. Psychological treatment strategy for chronic low back pain. Spine Surg Relat Res 2019;3:199–206. 10.22603/ssrr.2018-0050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wertli MM, Eugster R, Held U, et al. Catastrophizing-a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2639–57. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge K, et al. Symptoms of depression as a prognostic factor for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2016;16:105–16. 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet 2018;391:2384–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30488-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane back review group. Spine 2000;25:2688–99. 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman BM, Papas RK, Chatkoff DK, et al. Meta-Analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychol 2007;26:1–9. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012;12:162. 10.1186/1472-6882-12-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson S, Cramp F. Combining a psychological intervention with physiotherapy: a systematic review to determine the effect on physical function and quality of life for adults with chronic pain. Physical Therapy Reviews 2018;23:214–26. 10.1080/10833196.2018.1483550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 2001;322:1511–6. 10.1136/bmj.322.7301.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva Guerrero AV, Maujean A, Campbell L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological interventions delivered by physiotherapists on pain, disability and psychological outcomes in musculoskeletal pain conditions. Clin J Pain 2018;34:1–57. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitoula K, Venneri A, Varrassi G, et al. Behavioral therapy approaches for the management of low back pain: an up-to-date systematic review. Pain Ther 2018;7:1–12. 10.1007/s40122-018-0099-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic Low‐Back pain. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2010;7:CD002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Calderon J, Flores-Cortés M, Morales-Asencio JM, et al. Conservative interventions reduce fear in individuals with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020;101:329–58. 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.08.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung EJ, Hur Y-G, Lee B-H. A study of the relationship among fear-avoidance beliefs, pain and disability index in patients with low back pain. J Exerc Rehabil 2013;9:532–5. 10.12965/jer.130079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrari S, Chiarotto A, Pellizzer M, et al. Pain self-efficacy and fear of movement are similarly associated with pain intensity and disability in Italian patients with chronic low back pain. Pain Pract 2016;16:1040–7. 10.1111/papr.12397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Campos TF. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management NICE Guideline [NG59]. J Physiother 2017;63:120. 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–30. 10.7326/M16-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:493–505. 10.7326/M16-2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Ailiet L, et al. Low back pain and radicular pain: assessment and management.. KCE Report. 2017;287. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toward Optimized Practice (TOP) and Low Back Pain Working Group Evidence-Informed primary care management of low back pain: clinical practice guideline. 3rd edn Edmonton, AB, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018;391:2368–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain 1999;80:1–13. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00255-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielson WR, Weir R. Biopsychosocial approaches to the treatment of chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2001;17:S114–27. 10.1097/00002508-200112001-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Keeffe M, O'Sullivan P, Purtill H, et al. Cognitive functional therapy compared with a group-based exercise and education intervention for chronic low back pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). Brit J Sport Med 2020;54:782–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godfrey E, Wileman V, Galea Holmes M, et al. Physical therapy informed by acceptance and commitment therapy (PACT) versus usual care physical therapy for adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain 2020;21:71–81. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Synnott A, O'Keeffe M, Bunzli S, et al. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother 2015;61:68–76. 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexanders J, Anderson A, Henderson S. Musculoskeletal physiotherapists' use of psychological interventions: a systematic review of therapists' perceptions and practice. Physiotherapy 2015;101:95–102. 10.1016/j.physio.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holopainen R, Simpson P, Piirainen A, et al. Physiotherapists' perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain 2020;161:1150–68. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner T, Refshauge K, Smith L, et al. Physiotherapists' beliefs and attitudes influence clinical practice in chronic low back pain: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. J Physiother 2017;63:132–43. 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for decision making 1: introduction. Med Decis Making 2013;33:597–606. 10.1177/0272989X13487604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:80–97. 10.1002/jrsm.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansen JP, Naci H. Is network meta-analysis as valid as standard pairwise meta-analysis? it all depends on the distribution of effect modifiers. BMC Med 2013;11:159. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagg MK, Salanti G, McAuley JH. Comparing interventions with network meta-analysis. J Physiother 2018;64:128–32. 10.1016/j.jphys.2018.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efthimiou O, Debray TPA, van Valkenhoef G, et al. GetReal in network meta-analysis: a review of the methodology. Res Synth Methods 2016;7:236–63. 10.1002/jrsm.1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.Ann Intern Med 2009;151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hutton B, Catalá-López F, Moher D. [The PRISMA statement extension for systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analysis: PRISMA-NMA]. Med Clin 2016;147:262–6. 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JP, Chandler J, Cumpston M. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0, 2019. Available: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Accessed Jul 2019].

- 45.Savigny P, Kuntze S, Watson P, et al. Low back pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Analytics C. Endnote X9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Covidence Covidence systematic review software. veritas health innovation. Melbourne, Australia. Available: https://www.covidence.org/

- 48.Chiarotto A, Boers M, Deyo RA, et al. Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain. Pain 2018;159:481–95. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clement RC, Welander A, Stowell C, et al. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop 2015;86:523–33. 10.3109/17453674.2015.1036696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.George SZ, Valencia C, Beneciuk JM. A psychometric investigation of fear-avoidance model measures in patients with chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40:197–205. 10.2519/jospt.2010.3298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caldwell DM, Welton NJ. Approaches for synthesising complex mental health interventions in meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:16–21. 10.1136/eb-2015-102275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anheyer D, Haller H, Barth J, et al. Mindfulness-Based stress reduction for treating low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:799–807. 10.7326/M16-1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semple RJ. Does mindfulness meditation enhance attention? A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2010;1:121–30. 10.1007/s12671-010-0017-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holden J, Davidson M, O'Halloran PD. Health coaching for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:950–62. 10.1111/ijcp.12444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boehmer KR, Barakat S, Ahn S, et al. Health coaching interventions for persons with chronic conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev 2016;5:146. 10.1186/s13643-016-0316-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, et al. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine 2014;39:1449–57. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Savovic J, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2016;10:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eldridge S, Campbell M, Campbell M, et al. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (rob 2.0): additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 60.StataCorp Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61.White IR. Network meta-analysis. Stata J 2015;15:951–85. 10.1177/1536867X1501500403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White IR. Multivariate Random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J 2009;9:40–56. 10.1177/1536867X0900900103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White IR. Multivariate Random-effects meta-regression: updates to Mvmeta. Stata J 2011;11:255–70. 10.1177/1536867X1101100206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, et al. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013;8:e76654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chaimani A, Salanti G. Visualizing assumptions and results in network meta-analysis: the network graphs package. Stata J 2015;15:905–50. 10.1177/1536867X1501500402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:25. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gurung T, Ellard DR, Mistry D, et al. Identifying potential moderators for response to treatment in low back pain: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2015;101:243–51. 10.1016/j.physio.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang RAH, Nelson-Coffey SK, Layous K, et al. Moderators of wellbeing interventions: why do some people respond more positively than others? PLoS One 2017;12:e0187601. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DasMahapatra P, Chiauzzi E, Pujol LM, et al. Mediators and moderators of chronic pain outcomes in an online self-management program. Clin J Pain 2015;31:404–13. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rojiani R, Santoyo JF, Rahrig H, et al. Women benefit more than men in response to College-based meditation training. Front Psychol 2017;8:551. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Faber T, et al. Empirical evaluation of which trial characteristics are associated with treatment effect estimates. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;77:24–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2658–78. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cipriani A, Higgins JPT, Geddes JR, et al. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:130–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chaimani A, Caldwell DM, Li T. Chapter 11: undertaking network meta-analyses In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., eds Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0, 2019. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 76.Higgins JPT, Jackson D, Barrett JK, et al. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:98–110. 10.1002/jrsm.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chaimani A, Salanti G. Using network meta-analysis to evaluate the existence of small-study effects in a network of interventions. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:161–76. 10.1002/jrsm.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine CINeMA: Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis, 2017. Available: cinema.ispm.unibe.ch

- 80.Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003082. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papakonstantinou T, Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, et al. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta‐analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2020;16:e1080 10.1002/cl2.1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wood L, Hendrick PA, Systematic Review A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain neuroscience education for chronic low back pain: short-and long-term outcomes of pain and disability. Eur J Pain 2019;23:234–49. 10.1002/ejp.1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034996supp001.pdf (99.8KB, pdf)