Abstract

Persistent inward currents (PICs) are responsible for amplifying motoneuronal synaptic inputs and contribute to generating normal motoneuron activation. Delta-F (ΔF) is a well-established method that estimates PICs in humans indirectly from firing patterns of individual motor units. Traditionally, motor unit firing patterns are obtained by manually decomposing electromyography (EMG) signals recorded through intramuscular electrodes (iEMG). A previous iEMG study has shown that in humans the elbow extensors have higher ΔF than the elbow flexors. In this study, EMG signals were collected from the ankle extensors and flexors using high-density surface array electrodes during isometric sitting and standing at 10–30% maximum voluntary contraction. The signals were then decomposed into individual motor unit firings. We hypothesized that comparable to the upper limb, the lower limb extensor muscles (soleus) would have higher ΔF than the lower limb flexor muscles [tibialis anterior (TA)]. Contrary to our expectations, ΔF was higher in the TA than the soleus during sitting and standing despite the difference in cohort of participants and body positions. The TA also had significantly higher maximum discharge rate than the soleus while there was no difference in rate increase. When only the unit pairs with similar maximum discharge rates were compared, ∆F was still higher in the TA than the soleus. Future studies will focus on investigating the functional significance of the findings.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY With the use of high-density surface array electrodes and convolutive blind source separation algorithm, thousands of motor units were decomposed from the soleus and tibialis anterior muscles. Persistent inward currents were estimated under seated and standing conditions via delta-F (∆F) calculation, and the results showed that unlike the upper limb, the flexor has higher ∆F than the extensor in the lower limb. Future studies will focus on functional significance of the findings.

Keywords: delta-F, EMG, motor control, motor neuron, PICs

INTRODUCTION

All motor commands act through motoneurons to activate muscles. Studies in animal preparations, however, have shown that the electrical properties of motoneurons are complex. For example, voltage-dependent persistent inward currents (PICs) allow spinal motoneurons to continuously discharge action potentials even after the input to the cell ceases (Eken et al. 1989; Powers and Binder 2001). Moreover, PICs are capable of amplifying motoneuronal synaptic inputs three- to fivefold (Binder et al. 2002; Lee and Heckman 2000; Prather et al. 2001) and it is hypothesized that PICs play a role in maintaining postural muscle activation (Brownstone 2006; Heckman et al. 2009; Johnson and Heckman 2010).

PICs are strongly facilitated by monoamines such as serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE), which are released by axons originating in the brainstem (Hounsgaard et al. 1988; Lee and Heckman 1999). Kiehn et al. (1996) showed that selective depletion of 5-HT and NE in the lumbar spinal cord of rats induce postural deficits (Kiehn et al. 1996). Cats with monoamine depletion also have severe deficits in posture and balance, despite unaffected stepping and locomotion (Steeves and Jordan 1980). Considerable evidence demonstrates the importance of PICs in motor control and pathological motor behaviors, emphasizing the importance of studying the functional role of PICs in humans (Gorassini et al. 2002a, 2002b, 2004). However, investigating the role of PICs in human motor control is challenging because it is too invasive to directly measure the synaptic inputs of human spinal motoneurons.

To record the discharge of human spinal motoneurons, we exploited their key property, which is a 1-to-1 ratio between the discharge rate of a motoneuron and the activation of muscle fibers that it innervates (Buchthal and Schmalbruch 1980). Due to a large number of muscle fibers innervated by each motoneuron, the individual waveform of muscle fibers reflects an amplified version of the discharge pattern of the parent motoneuron. The electromyography (EMG) signals from muscle fibers can be recorded using intramuscular electrodes, making the spinal motoneurons the only cells in the central nerouvs system (CNS) whose individual firing patterns can be routinely measured in intact humans. A 64-channel high-density surface array electrodes (HD-sEMG) combined with automated decomposition algorithms can capture several tens of concurrently active motor units (Holobar et al. 2010; Nawab et al. 2010; Negro et al. 2016).

Gorassini and colleagues (Gorassini et al. 1998, 2002a, 2002b) developed an indirect method to estimate the amplitudes of PICs in humans, termed delta-F (ΔF). ΔF is calculated from pair-wise comparison of decomposed motor units from EMG signals, and it quantifies PIC activation during voluntary contractions (Gorassini et al. 2002a). Previously, ΔF has been calculated in humans from EMG signals collected through fine-wire intramuscular electrodes (iEMG) (Stephenson and Maluf 2011; Wilson et al. 2015). However, iEMG is not only invasive in nature but also can only capture EMG signals from a small number of motor units per contraction (Duchateau and Enoka 2011). This study attempted to apply the noninvasive HD-sEMG technology to a well-established ΔF approach to estimate PIC magnitude in humans. The extensive data provided by HD-sEMG have potential to study motoneuron properties more in depth than iEMG (Collins et al. 2002; Farina and Negro 2015; Muceli et al. 2015).

PIC magnitude may not be equal between motor pools. For example, in cat motoneurons, plateau potentials of extensor motoneurons are more easily evoked than in the flexors (Hounsgaard et al. 1988). A recent study showed that the neck extensor motoneurons in cats have higher dendritic contacts from 5-HT and NE boutons than the flexor motoneurons (Maratta et al. 2015). Consistent with findings in cat motoneurons, we have shown that, in the human upper limb, the elbow extensors have higher ΔF than the flexors (Wilson et al. 2015). The goal of this study was to establish the ankle flexor-extensor relationship in the human lower limb, using the latest motor unit decomposition technology. Characterized as ΔF, the magnitude of PICs during isometric force generation in the soleus and the tibialis anterior (TA) was measured in sitting and standing conditions. Because of the potentially important role of PICs in posture (Eken et al. 1989) and the greater PICs in extensors than flexors in the cat and human upper limb data, we hypothesized that the soleus would have higher ΔF than the TA in both sitting and standing positions.

METHODS

Participants and Ethical Approval

A total of 23 young subjects with no history of neurological or motor disorders participated in the study. Twelve subjects (aged 25 ± 3.6 yr, 4 women) participated in the sitting down experiment and 11 subjects (aged 32.6 ± 14.4 yr, 4 women) participated in the standing up experiment. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University. All subjects signed informed consent form before participating in the study.

Experimental Procedures

Seated experiment.

Participants were asked to sit in a Biodex experimental chair (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) and secured with shoulder and thigh straps to minimize change in position. Each participant’s dominant foot (2 left, 10 right) was attached to an ankle attachment, which was anchored to Systems 2 Dynanometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY) to measure the dorsi- and plantarflexion torque. Unless the participant expressed discomfort, the ankle was positioned at 10° plantarflexion and the knee was positioned at 20° flexion. EMG signals were recorded from the soleus and TA muscles. Before the surface arrays were applied, any excess hair was removed, and the skin was lightly abraded and cleaned. After electrodes were applied, each participant was asked to plantarflex and dorsiflex to the participant’s maximum effort in an isometric condition up to three times. If one of the trials was less than 90% of the highest trial or the last trial was clearly the highest, another maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) was performed. MVC was calculated by taking the mean of three trials with the highest MVCs. Participants were provided with a target line as well as live feedback of their torque (LabVIEW, National Instruments, Austin, TX), and their task was to trace the target line with their torque feedback. Depending on the trial, the peak of the target varied between 10% and 30% of each participant’s MVC. Before data collection, participants practiced until they were able to smoothly trace the target line to the best of their abilities. During data collection, participants generated two identical ramps (10 s ascending and 10 s descending) per trial interleaved with 10 s rest. Each trial was repeated up to 3 times and there were total of 12 trials (3 × 10% MVC dorsiflexion and plantar flexion each, 3 × 30% MVC dorsiflexion and plantar flexion each). The trials were presented in a randomized order.

Standing experiment.

Participants were fitted into multiple degree of freedom (DOF), lower extremity isometric device (the MultiLEIT, Sánchez et al. 2015) and secured with a harness and bracing. The foot of the tested leg was casted and secured to two 6 DOF load cells to collect joint torque. Participants were positioned to 10° hip abduction, 20° hip flexion, 25° knee flexion, and neutral angle about the ankle. Before the surface arrays were applied, any excess hair was removed, the skin was lightly abraded, and cleaned. EMG signals were collected from the soleus and TA muscles. Each participant’s MVC was measured during ankle plantarflexion and dorsiflexion, and real-time visual feedback was provided (MATLAB, MathWorks, Natick, MA). Participants were asked to reach their MVC as rapidly as possible and stay at the peak for at least 1 s. Participants were then asked to generate two isometric ramp contractions (10 s ascending and 10 s descending) to 20% of their respective MVC. Each trial was repeated up to three times.

Data Collection

Surface EMG.

Surface EMG recordings were collected through a 64-channel high-density surface array electrode (HD-sEMG) from the soleus and the TA muscles. The array consisted of 64 (13 rows × 5 columns) gold-coated electrodes with a 1-mm diameter and 8-mm interelectrode distance (ELSCH064NM2, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy). The location of the muscles was identified through palpation before arrays were placed. The arrays were attached to the skin by biadhesive foam (KITAD064, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy), and the skin to electrode contact was optimized by filling the wells of the adhesive foam with conductive cream (CC1, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy). The HD-sEMG signals were collected in differential mode, through one of two amplifiers: a 12-bit A/D with ×1,000 amplification (USB2, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy) or a 16-bit A/D with ×150 amplification (Quattrocento, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy). Both amplifiers filtered the signal at 10–900 Hz and digitized at a rate of 2,048 Hz.

Intramuscular EMG.

From three of the seated experiment participants, intramuscular EMG signals (iEMG) were collected simultaneously with HD-sEMG signals. Up to three pairs of perpendicularly cut, bared, 75-μm stainless-steel fine wires (Charlgren Enterprises, Gilroy, CA) were inserted into the soleus and TA via a 23-gauge needle. HD-sEMG were placed over the wires for simultaneous EMG collection between the two sources. iEMG signals are amplified (1–10 k) and sampled at 10,240 Hz (Quattrocento, 384-channel EMG amplifier, OT Bioelettronica, Turin, Italy).

Motor Unit Decomposition

Surface EMG.

Before decomposition, HD-sEMG signals were visually inspected and any channels with substantial artifacts or noise were removed. The remaining HD-sEMG data were decomposed based on convolutive blind source separation to provide motor unit spike train (Negro et al. 2016). The silhouette (similar to normalized measure of signal to noise ratio, see Negro et al. 2016) threshold for decomposition was 0.87.

Intramuscular EMG.

iEMG signals were decomposed into individual motor units using the open source EMGLab software (McGill et al. 2005). During decomposition, signals were high-pass filtered (1,000 Hz) and a template-matching algorithm automatically created templates, classified individual motor unit action potentials, and presented the residual signal. The remaining signals were manually inspected and decomposed to match either an existing template or into a new template. Spike times were then converted into instantaneous firing rates by calculating the reciprocal of the interspike interval.

Data Analysis

PIC estimation.

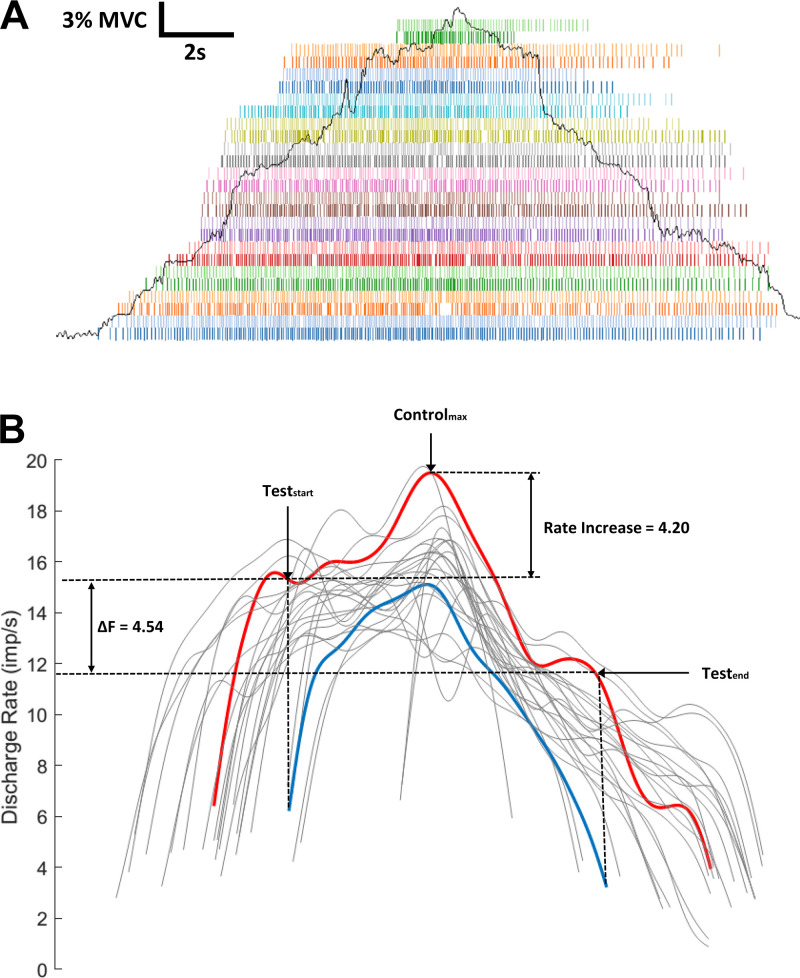

A pairwise motor unit comparison technique, termed ΔF, was employed in this study to indirectly estimate the level of PICs in motoneurons that innervate the soleus and the TA. Figure 1B shows smoothed discharge rates of 26 motor units from the human TA in response to a slow isometric ramp contraction. Units in red and blue illustrate ΔF calculation of pairwise comparison. The earlier recruited unit is termed the control unit (red), and the later recruited unit is termed the test unit (blue). The control unit was used as a reporter of changes in the net excitatory synaptic input to the motoneuron pool, and ΔF was calculated by taking the frequency difference between the onset and the offset of the test unit in terms of the control unit (Bennett et al. 2001; Gorassini et al. 1998). This paired motor unit analysis technique has been used extensively (Herda et al. 2016; Mottram et al. 2009; Stephenson and Maluf 2011; Udina et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2015) and validated by experiments in animal preparations (Powers et al. 2008).

Fig. 1.

Pairwise comparison example. A: firing pattens of 26 motor units from the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle during a single 30% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) plantarflexion contraction. The ramp represents the torque trace produced by the participant and lasted for 20 s (10 s ascending and 10 s descending). B: discharge rates of 26 motor units after smoothed by 2-s hanning window. Delta-F (ΔF) was calculated as the difference in discharge rate between the onset and offset of the test unit (blue) in terms of the control unit (red). Rate increase is the difference between the onset of test unit (Teststart) and the peak of control unit (Controlmax).

Parameters to estimate PICs.

The pairwise comparison technique assumes that the control and test units share common synaptic drive, and several studies have reported the coefficient of determination (r2) as a measure of common synaptic modulation between the two concurrently firing units (Gorassini et al. 2004; Powers et al. 2008; Stephenson and Maluf 2011; Udina et al. 2010). Previous studies have commonly used r2 value of 0.5–0.7 as a threshold, and in this study, any pairs with r2 value of less than 0.7 were excluded from data analysis (Foley and Kalmar 2019; Wilson et al. 2015).

A simulation study has shown that there is a large variability in ΔF when the recruitment time difference between the test and control units is less than 500 ms (Powers and Heckman 2015). The high variability is possibly due to the initial acceleration phase of motor unit firing, which signifies activation of PICs (Johnson et al. 2017). Therefore, any unit pairs with a recruitment time difference less than 500 ms were excluded from analysis.

The rate-rate slope of each motor unit pair was also analyzed to gain understanding of the distribution of synaptic input to the motor unit pool (Gorassini et al. 2002a; Johnson et al. 2017; Powers et al. 2012; Powers and Binder 2001). The instantaneous firing rates of both motor units were first smoothed by 2-s hanning window. The rate-rate slope was then calculated by plotting firing rate of the test unit against the firing rate of the control unit during the descending phase of ramp contraction (Monster and Chan 1977). The higher the rate-rate slope, the greater the tendency for synaptic inputs to be relatively larger in high than low threshold units (Johnson et al. 2017).

To ensure the difference in ∆F is not due to difference in firing rate ranges of motor units, a bootstrap technique was applied. We randomly selected 10 soleus unit pairs and compared their mean maximum discharge rates to mean maximum discharge rates of 10 randomly selected TA unit pairs. If the difference was within ±0.02 imp/s, we noted their mean ∆F values. If the difference was bigger than ±0.02 imp/s, we repeated the comparison up to 10,000 times (each time is 10 randomly selected TA unit pairs). This was repeated 5,000 times with replacement.

Rate of agreement.

The rate of agreement (RoA) between HD-sEMG and iEMG decomposition was used as a conservative estimate of accuracy and was defined by the following equation (Negro et al. 2016):

DC represents the number of discharges common to the both sources within 0.5 ms of one another. DA represents the number of discharges identified only by HD-sEMG. DW represents the number of discharges identified only by iEMG. This approach treats each discharge equally, without any bias toward either sources, and provides a normalized value, where 100% is a perfect correspondence between HD-sEMG and iEMG.

Statistical Analysis

Values are reported as means ± SD, unless otherwise noted. The mean ΔF and rate increase were calculated in each muscle in each subject and then averaged across subjects. Differences in the average ∆F and rate increase of each subject were evaluated by using a mixed linear model with muscles as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. Post hoc analyses were conducted with the Tukey honestly significant difference test. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05, and the Cohen’s d was used to estimate the effect size (ES) (Cohen 1988).

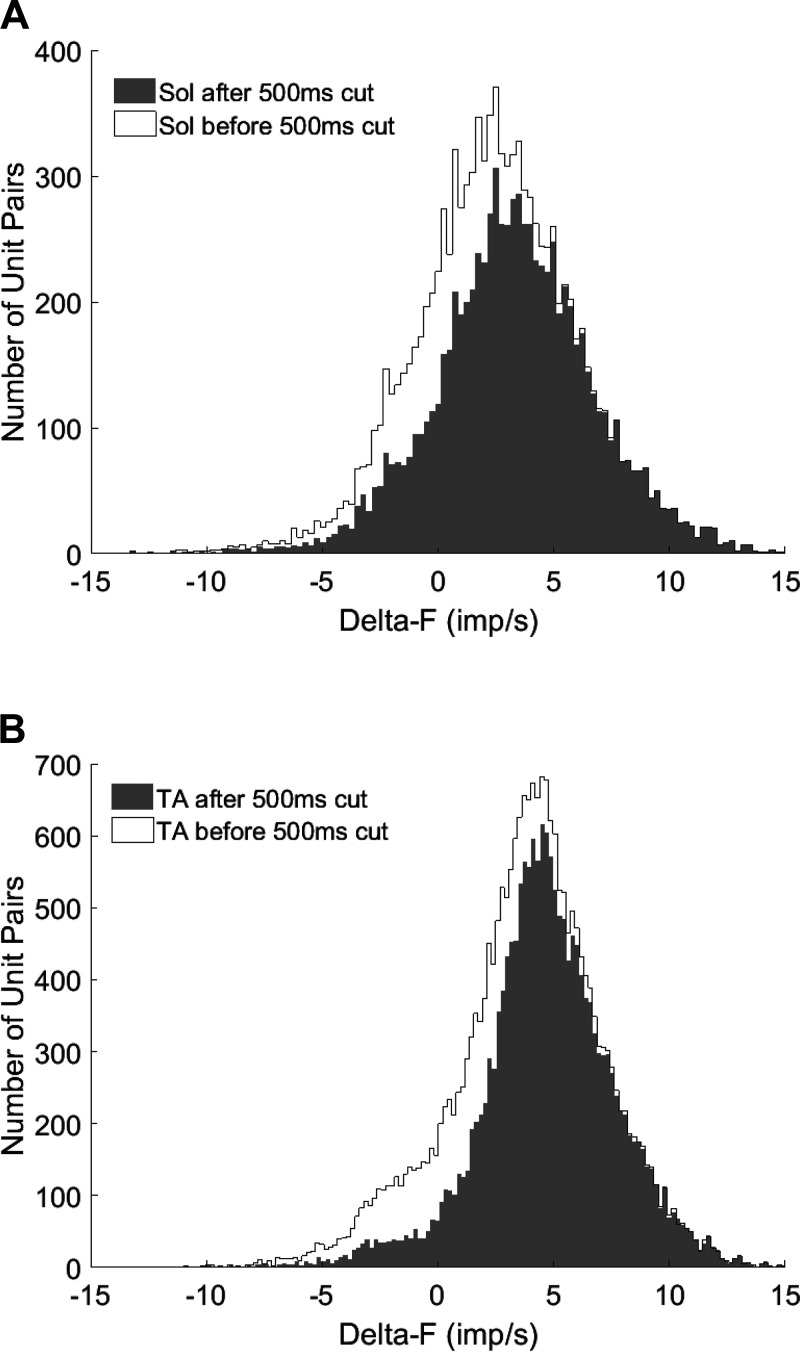

RESULTS

Motor Unit Yield

For the seated experiment, a total of 1,259 (8.7 ± 3.0 per contraction) and 1,699 (10 ± 6.5 per contraction) motor units were collected from the soleus and the TA, respectively. From these spike trains 10,819 and 23,121 motor unit pairs had r2 values greater than 0.7. After we eliminated pairs with less than 500-ms recruitment time difference, 8,443 soleus and 17,987 TA motor unit pairs remained for final analysis (Fig. 2). For the standing experiment, a total of 756 (8.7 ± 5.3 per contraction) and 1,395 (17.7 ± 6.8 per contraction) motor units were collected from the soleus and TA. After controlling for r2 values, 2,379 soleus and 8,637 TA motor unit pairs remained, and 1,749 soleus and 6,486 TA motor unit pairs were included in the final analysis after controlling for 500-ms recruitment time difference.

Fig. 2.

Delta-F (ΔF) distribution before and after eliminating unit pairs with less than 500 ms recruitment time difference. A: before controlling for the recruitment time difference, 10,819 unit pairs were observed from the soleus. After making the 500-ms recruitment time difference cut, 8,443 unit pairs remained for analysis. B: there were 23,121 unit pairs observed from the tibialis anterior (TA) before controlling for the recruitment time difference. After, 17,987 unit pairs remained for analysis. For both muscles, eliminated unit pairs mostly had lower ΔF than remaining unit pairs. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test verified that the ΔF distributions are not statistically different than normal (P < 0.0001).

Silhouette Values

During seated experiment, the soleus units had a mean silhouette values of 0.97 ± 0.0067 and 0.92 ± 0.0049 at 10% and 30% effort levels. The TA units had a mean silhouette values of 0.92 ± 0.0048 and 0.92 ± 0.0040 at 10% and 30% effort levels. During standing experiment, the soleus had 0.93 ± 0.0049 and the TA had 0.93 ± 0.0030 silhouette values at 20% effort level.

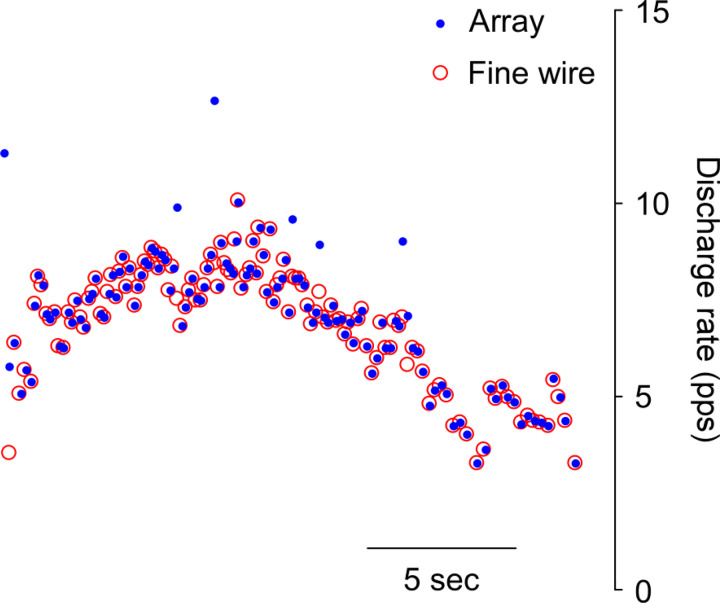

Rate of Agreement

Through fine-wire recordings, a total of 252 soleus (7 ± 5.6 units per trial) and 65 TA units (1.8 ± 1.3 units per trial) were collected during sitting isometric force generation. A total of 34 soleus units were identified from both HD-sEMG and iEMG, whereas only 5 TA units were detected from the both sources. Figure 3 represents a common motor unit to both iEMG and HD-sEMG with RoA of 93.9%, during a single contraction in the soleus. On average, RoA between the two sources was 86.0 ± 10.6% and 90.8 ± 4.5% for the soleus and TA, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Example of a motor unit identified from both sources during a 10% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) trial in the soleus. The rate of agreement (RoA) between intramuscular EMG (iEMG) and surface EMG (sEMG) in this example is 93.9%.

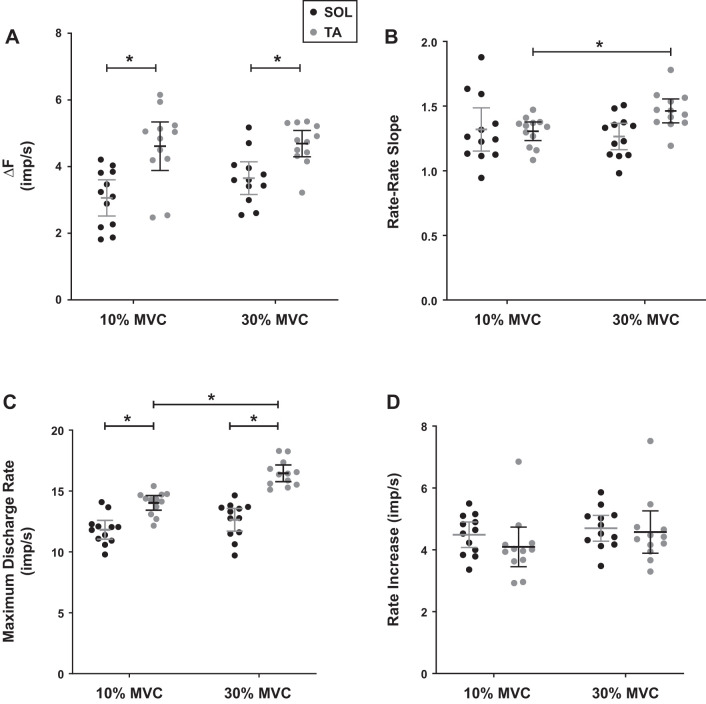

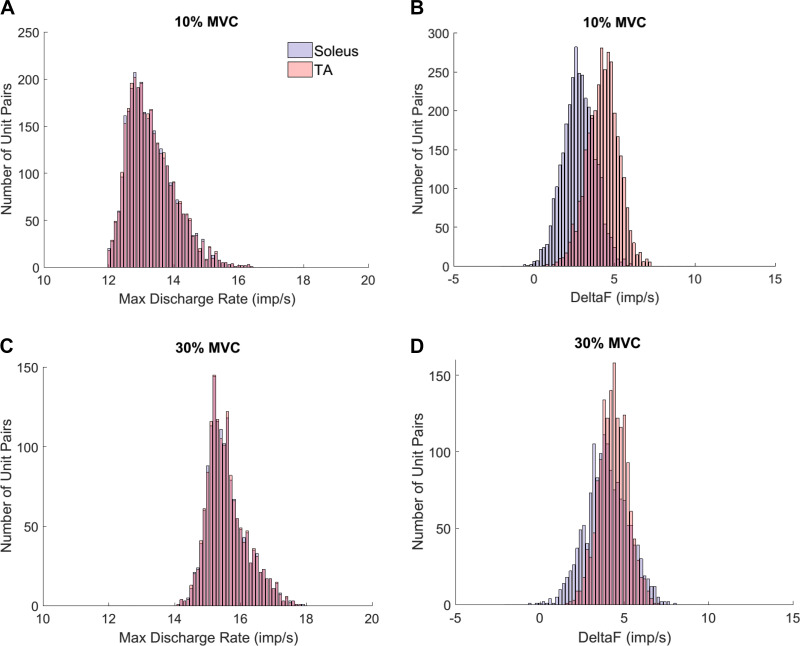

Sitting Isometric Force Generation

Under 10% effort level, the soleus and the TA showed ΔF values of 3.06 ± 0.86 imp/s and 4.61 ± 1.15 imp/s, and under 30% effort level, they were 3.65 ± 0.77 imp/s and 4.69 ± 0.62 imp/s, respectively. The results showed that during sitting isometric force generation, the TA exhibited significantly higher ΔF than the soleus in both 10% (P < 0.0001; ES = 1.53) and 30% (P = 0.0039; ES = 1.49) effort levels (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, within muscles, there was no statistical significance in ΔF between 10% and 30% effort levels (soleus P = 0.089; ES = 0.72; TA P = 0.82; ES = 0.087).

Fig. 4.

Mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) is shown for sitting experiment. A: delta-F (ΔF) was significantly higher in the tibialis anterior (TA) than the soleus during 10% (P < 0.0001) and 30% (P < 0.0039) maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) conditions. Increasing the effort level did not change ∆F values in both muscles. From left to right, the mean ∆F values were 3.06 ± 0.86 imp/s, 4.61 ± 1.15 imp/s, 3.65 ± 0.77 imp/s, and 4.69 ± 0.62 imp/s. B: the mean rate-rate slopes of the soleus and TA at 10% MVC were 1.31 ± 0.26 and 1.32 ± 0.11 and at 30% MVC were 1.26 ± 0.16 and 1.46 ± 0.15. The rate-rate slope of the soleus did not change significantly between effort levels (P = 0.43), but the rate-rate slope of the TA did (P = 0.0254). Statistical difference was observed between the muscles at 30% MVC (P = 0.0056) but not at 10% MVC (P = 0.84). C: the mean maximum discharge rates of the test units at 10% MVC were 11.82 ± 1.21 imp/s and 14.03 ± 0.95 imp/s and at 30% MVC were 12.64 ± 1.47 imp/s and 16.46 ± 1.07 imp/s. The maximum discharge rate of the soleus did not change significantly between effort levels (P = 0.063), while statistical significance was observed in the TA (P < 0.0001). The maximum discharge rates between muscles were also significantly different at both effort levels (P < 0.0001). D: rate increase did not change significantly between conditions. From left to right, the values were 4.48 ± 0.65 imp/s, 4.09 ± 1.01 imp/s, 4.70 ± 0.66 imp/s, and 4.60 ± 1.10 imp/s.

Figure 4B shows the soleus rate-rate slope was 1.31 ± 0.26 at 10% effort level and when the effort level was increased to 30%, there was no significant change in the slope (1.26 ± 0.16) (P = 0.43; ES = 0.23). On the contrary, the TA rate-rate slope significantly increased from 1.32 ± 0.11 at 10% to 1.46 ± 0.15 at 30% effort level (P = 0.0254; ES = 1.064). There was no statistical difference between the rate-rate slope of the soleus and the TA at 10% effort level (P = 0.84; ES = 0.050), but the difference exceeded the threshold for statistical significance when the effort level was increased to 30% (P = 0.0056; ES = 1.29). These results were consistent with a previous study showing that rate-rate slopes are generally greater than 1.0 (Bennett et al. 2001; Monster and Chan 1977).

During sitting isometric force generation, the test units of the soleus had an average maximum discharge rates of 11.82 ± 1.21 imp/s at 10% and 12.64 ± 1.47 imp/s at 30% MVC. Despite a slight increase in maximum discharge rates, there was no statistical significance between effort levels (P = 0.063; ES = 0.61). The test units of the TA had average maximum discharge rates of 14.03 ± 0.95 imp/s at 10% and 16.46 ± 1.07 imp/s at 30%. Unlike the soleus, there was a statistical difference between effort levels in the TA (P < 0.0001; ES = 2.40). The maximum discharge rates were statistically different between the muscles at both effort levels with large effect sizes, with soleus tending to have lower rates (P < 0.0001 for soleus and TA; ES = 2.03 at 10%; ES = 2.97 at 30%) (Fig. 4C). The results showed that the soleus rate increase values were 4.48 ± 0.65 imp/s at 10% effort level and 4.09 ± 1.01 imp/s at 30% effort level. There was no statistical difference between effort levels (P = 0.53; ES = 0.26). The TA rate increase values were 4.70 ± 0.66 imp/s at 10% effort level and 4.60 ± 1.10 imp/s at 30% effort level. There was no statistical difference between effort levels in TA either (P = 0.15; ES = 0.38). There was also no statistical difference between muscles (P = 0.24; ES = 0.41 at 10% and P = 0.71; ES = 0.12 at 30% effort level).

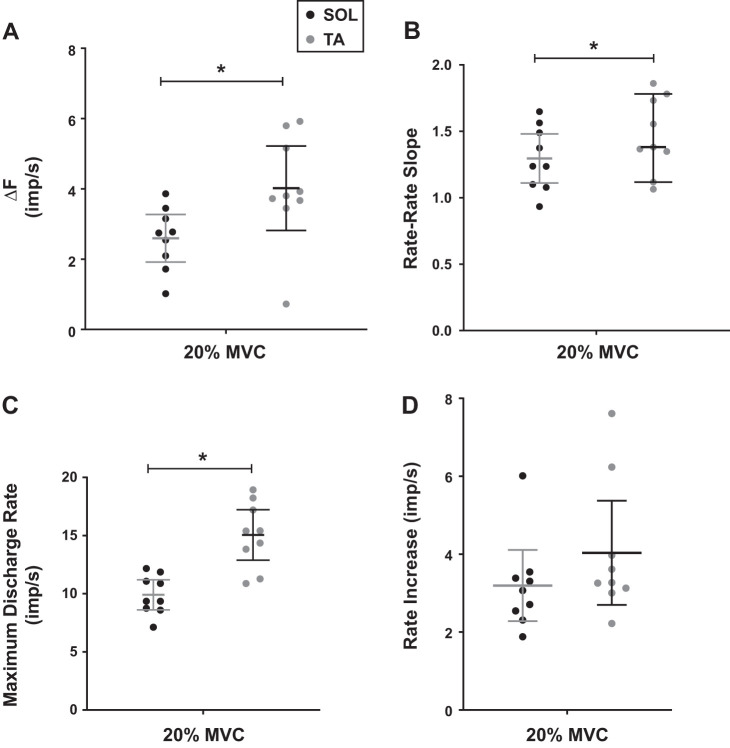

Standing Isometric Force Generation

Figure 5A shows that during standing isometric force generation at 20% MVC, the TA (ΔF = 4.02 ± 1.56 imp/s) exhibited significantly higher ΔF than the soleus (ΔF = 2.59 ± 0.88 imp/s) (P = 0.022; ES = 1.13). Figure 5B shows that the TA rate-rate slope during standing (1.47 ± 0.28) was significantly higher than the rate-rate slope of the soleus (1.30 ± 0.24) (P = 0.0042; ES = 0.65). As shown in Fig. 5C, the soleus and the TA test units had mean maximum discharge rates of 9.90 ± 1.69 imp/s and 15.05 ± 2.82 imp/s, with statistical significance between them (P < 0.0001; ES = 2.22). Figure 5D shows the rate increase in the soleus was 3.19 ± 1.19 imp/s and in the TA was 4.04 ± 1.74 imp/s. No statistical significance was observed between the muscles (P = 0.44; ES = 0.56).

Fig. 5.

Mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) is shown for standing experiment. *Statistically significant (P < 0.05). A: at 20% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), the mean delta-F (ΔF) of the soleus was 2.59 ± 0.88 imp/s and the tibialis anterior (TA) was 4.02 ± 1.56 imp/s, and there was a statistical significance between them (P = 0.022). B: at 20% MVC, the mean rate-rate slopes of the soleus and the TA were 1.30 ± 0.24 and 1.47 ± 0.28 and they were statistically different (P = 0.0042). C: at 20% MVC, the mean maximum discharge rates of the test units were 9.90 ± 1.69 imp/s for the soleus and 15.05 ± 2.82 imp/s for the TA and they were statistically different (P < 0.0001). D: the mean rate increase did not show statistical difference between muscles. Their values were 3.19 ± 1.19 imp/s for the soleus and 4.04 ± 1.74 imp/s for the TA (P = 0.44).

Comparisons at Matched Firing Rates

The lack of difference in firing rate increase between soleus and TA indicates that the higher peak firing rate of TA was not the source of its higher delta ∆F amplitudes. To further investigate this issue, ∆F was compared between the muscles with the unit pairs that had similar maximum discharge rates in control units. After 5,000 comparisons, 3,196 (10% MVC sitting), 1,524 (30% MVC sitting), and 40 (20% MVC standing) unit pairs had qualifying matching maximum discharge rates. As shown in Fig. 6, A and C, the unit pairs included in the analysis had almost identical mean maximum discharge rates between the soleus and TA (13.35 ± 0.75 imp/s for 10% effort level and 15.64 ± 0.62 imp/s for 30% effort level). However, in both effort levels, ∆F was still significantly higher (P < 0.00001) in the TA than the soleus (Fig. 6, B and D). Also, during standing, the mean maximum discharge rates of the unit pairs were almost identical (14.02 ± 0.38 imp/s) and ∆F was still significantly higher (P = 0.0037) in the TA (3.87 ± 0.82 imp/s) than the soleus (3.23 ± 0.85). These results for matching firing rates are consistent with the lack of difference in rate increase (Figs. 4D and 5D), making it unlikely that higher peak firing rates accounted for the larger values for ∆F in TA compared with soleus.

Fig. 6.

Delta-F (ΔF) after matching maximum discharge rates. A: under 10% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) condition, there was no statistical difference between the maximum discharge rates of the matched soleus (13.35 ± 0.75 imp/s) and tibialis anterior (TA) (13.35 ± 0.75 imp/s) unit pairs (P = 0.50). B: the matched ∆F values of the soleus (2.87 ± 1.00 imp/s) and TA (4.38 ± 0.97 imp/s) units were significantly different (P < 0.00001). C: there was no statistical difference (P = 0.33) in maximum discharge rates between the muscles under 30% MVC condition (soleus = 15.64 ± 0.62; TA = 15.64 ± 0.62). D: statistical significance was observed between the matched ∆F values of the soleus (4.06 ± 1.27) and TA (4.44 ± 0.84) (P < 0.00001).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to estimate the contribution of PICs during isometric force generation and explore the flexor-extensor relationship in the ankle muscles. HD-sEMG signals were recorded from young adults, and the EMG signals were decomposed into discharge patterns of individual motor units for pair-wise comparison. The results suggest that contrary to our hypothesis, the TA has significantly higher ΔF values than the soleus.

ΔF Indirectly Measures PICs

In anesthetized cats, triangular current injection generates a relatively linear firing response in motoneurons. However, in decerebrate cats when PICs are facilitated by tonic descending monoaminergic drive, motoneurons respond in three distinct phases: initial acceleration, saturation, and hysteresis (Heckman and Enoka 2012; Powers and Binder 2001). Because PIC amplitude is directly proportional to the level of monoaminergic inputs, any of the three phases can be used to estimate PICs (Johnson et al. 2017). Estimates of ΔF are however highly variable when the acceleration phase is included (Kim et al. 2017), and the saturation phase is sensitive to the relative distribution of synaptic input on high versus low threshold motoneurons (Johnson et al. 2017). We thus focused on the ΔF calculation to indirectly quantify hysteresis generated by PICs (Gorassini et al. 1998, 2002a, 2002b; Kiehn and Eken 1997).

One of the assumptions of the ΔF calculation is that the motor unit pairs receive a common synaptic input. In order for the control unit to act as a reporter of changes in the net excitatory synaptic input to the motoneuron pool, the changes in discharge rate of the test unit should be highly correlated with the changes in the control unit. Therefore, it is generally assumed that the correlation coefficient r2 value greater than 0.7 would adequately estimate the excitatory net synaptic input to the motoneuron pool shared with the test unit (Gorassini et al. 2004; Powers et al. 2008; Stephenson and Maluf 2011; Udina et al. 2010).

Simulation of motor unit pairs has shown that when the control and test units have a recruitment time difference of less than 500 ms, there is a large variance in ΔF values (Powers and Heckman 2015). The initial acceleration phase of a motor unit discharge pattern indicates activation of the PIC, and if the pair-wise comparison is computed before the acceleration phase of the control unit is terminated, it can cause a large variance in ΔF. For the same reason, unit pairs with less than 500-ms recruitment time difference generally have lower ΔF values because they were captured prematurely (i.e., before PICs were fully activated). As shown in Fig. 2, any unit pairs that did not meet the criterion were excluded from further analysis.

Two Source Validation

The most stringent method of validating motor unit decomposition is recording the same motor unit from two separate sources and to compare their discharge patterns (Mambrito and De Luca 1984). This method assumes that it is highly unlikely to identify a faulty motor unit from two separate methods of recording and decomposition. The RoA values observed in this study as well as the proportion of the matched units are similar to previously reported values (Yavuz et al. 2015). The lower number of matched units can be attributed to the bias of sEMG decomposition toward more superficial units (Holobar et al. 2009). In addition, it has been previously shown that as the contraction speed increases, the number of lower threshold unit decomposed is decreased with sEMG (Hassan et al. 2019), which has not been reported in iEMG yet.

Greater ΔF in the TA than the Soleus

Our results showed that ΔF of the ankle flexors (i.e., TA) is larger than the ankle extensors (i.e., soleus), regardless of effort levels or body positions. These results were surprising for two reasons. First, the findings of the current study were contradictory to previous findings in the upper limb that showed that the extensor (i.e., triceps) had higher ΔF than the flexors (i.e., biceps) (Wilson et al. 2015), a relationship that is consistent with previous findings in decerebrate cat and neonatal rat preparations (Cotel et al. 2009; Hounsgaard et al. 1988). Surprisingly, our results showed that in the human lower limb, the flexor and extensor relationship was reversed. Moreover, this “reversed” relationship continued to hold during standing, a finding consistent with recent results showing that the ΔF of soleus motor units remains the same as a subject goes from sitting to standing (Foley and Kalmar 2019).

Second, the soleus exhibits tonic activation during postural control and PICs are important for maintaining prolonged self-sustaining firing (Hounsgaard et al. 1988; Sinkjaer et al. 2000). Our findings were especially surprising because the prolonged firing would seem to be a major advantage for maintenance of posture (Heckman and Johnson 2014). During standing in humans, the soleus is tonically active but TA is not (Day et al. 2013). Furthermore, during the sitting/isometric condition of our experiment, reciprocal Ia inhibition is much stronger onto TA than the soleus synergist medial gastrocnemius (Yavuz et al. 2018). Reciprocal inhibition is especially relevant because PICs are highly sensitive to this form of inhibition, with even small increases in length of antagonists causing large reductions in PIC amplitudes (Hyngstrom et al. 2007). Thus it is possible that L-type CaV1.3 channels or monoaminergic boutons are more highly expressed in the TA than the soleus in humans. In addition, these results might also suggest that TA motoneurons receive substantially stronger monoaminergic synaptic drive from the brainstem, more so than soleus motoneurons. It is possible that ∆F values can be limited by firing rate ranges of motor unit populations, and it might partly explain why ∆F was lower in the soleus than the TA. This possibility was explored by measuring rate increase, which is the maximum possible ∆F of a motor unit pair minus actual ∆F (Fig. 1B). As the rate increase approaches zero, the possibility of limiting ∆F gets bigger due to saturation. However, our results showed that there were large rate increases for every condition we measured, without any significant difference between them.

It is also possible that higher ∆F in the TA than the soleus is due to difference in overall firing rate ranges of the two motor unit populations. This difference however does not appear to affect our measurements of ∆F in the two muscles. Our analysis of rate increase (which is the increase in firing rate of the control unit from recruitment of the test unit to peak firing; see methods) was not different between TA and soleus (Figs. 4D and 5D). In addition, we compared ∆F values of motor unit pairs with similar maximum discharge rates (Fig. 6). The results showed that the TA still had significantly higher ∆F than the soleus under all conditions.

The Difference Between Bipeds and Quadrupeds

Although the difference between cat and human motoneurons is unexpected, it is not unwarranted. The muscle fiber composition of the soleus and the TA is a lot more similar in humans than cats (Johnson et al. 1973). Additionally, it has already been shown that cat and human ankle muscles respond differently to stimulation. For example, the spinal motoneurons of cats only show suppression during fictive locomotion (Gosgnach et al. 2000; Ménard et al. 2003; Perreault et al. 1999). However, in humans, during rhythmic arm movement, the TA H-reflex amplitude is modulated bidirectionally (suppression and facilitation), while the soleus only exhibits suppression (Dragert and Zehr 2009). It is possible that these differences are due to the fact that the ankle muscles of bipeds and quadrupeds serve different functional roles.

No Change in ΔF Between Effort Levels

Another surprising finding from this study was that during sitting isometric force generation, there was no statistical significance in ΔF between effort levels. A previous study has shown that with increasing background EMG, the H-reflex amplitude of the soleus increases (Capaday and Stein 1986, 1987; Edamura et al. 1991; Kido et al. 2004), and we expected to observe increase in ΔF as well due to increasing monoaminergic drive from the brainstem. Our results suggested that monoaminergic drive might stay approximately constant as the drive from other descending systems, such as the corticospinal tract, increases to produce more motor output. However, it is also possible that the difference in rates of rise (Revill and Fuglevand 2011) and/or activated motor unit populations between effort levels minimized the increased in ∆F.

Maximum Discharge Rates

Along with ∆F, the mean maximum discharge rate of the TA was significantly higher than the soleus under all conditions. Increasing effort level from 10% to 30% also significantly increased the mean maximum discharge rate of the TA, and although statistical significance was not reached, the mean maximum discharge rate of the soleus also increased. As descending commands strengthen, muscles produce more output by recruiting more units and increasing discharge rates. It is possible TA relies more on the latter strategy while increasing force output from 10% to 30% effort level. It is also unlikely that the higher maximum discharge rate of TA affected ∆F measurements for two reasons. First, there was no difference in rate increase between the muscles. Second, even after motor unit pairs were normalized by their maximum discharge rates, ∆F was still significantly higher in the TA than the soleus.

The Rate-Rate Slope and Its Sensitivity to Changes in Synaptic Inputs

As shown in Fig. 4B, the soleus rate-rate slope did not significantly change between effort levels. However, as the effort level increased, the rate-rate slope of the TA slightly, but significantly, increased. Rate-rate slope measures two factors: the relative share of the synaptic input to the two units and the relative behaviors of their intrinsic frequency to current slopes (including PIC effects) (Gorassini et al. 2002a; Powers et al. 2012; Powers and Binder 2001). If both factors are equivalent, rate-rate slope will be equal to 1.0 (Johnson et al. 2017). A slope greater than 1.0 indicates that either the higher threshold unit is more sensitive to a given increment in drive, due to a higher frequency-current slope, or it receives more excitatory input than the lower threshold unit. A tendency to generate greater synaptic current in F vs. S motoneurons is a hallmark of several descending systems, including the corticospinal and vestibulospinal inputs, whereas Ia input from the periphery has the opposite effect (Powers and Binder 2001). Thus a rate-rate slope greater than 1 may indicate a dominance of descending inputs in the overall motor command for increasing volitional torque. Because of this slope interact with intrinsic current slopes and PIC effects, it is however likely that spacing between the recruitment thresholds of motoneurons is a better index of synaptic distribution (Johnson et al. 2017). We plan further analyses using this approach.

Conclusion

In this study, we estimated the contribution of PICs during sitting and standing using the latest HD-sEMG technology. This study showed that, regardless of body position, the TA has higher ΔF than the soleus during isometric force generation. These results indicated the motoneurons that innervate TA receive more neuromodulatory inputs from the brainstem and generate stronger PICs. These results were surprising because they were contradictory to the results shown in human elbow and cat ankle muscles (Hounsgaard et al. 1988; Wilson et al. 2015). However, the difference between motoneuron excitability in humans and cats has been previously reported and therefore is not completely surprising (Dragert and Zehr 2009; Gosgnach et al. 2000; Ménard et al. 2003; Perreault et al. 1999). Increased effort levels did not significantly change ΔF values in either of the muscles, implying that the monoaminergic drive stays relatively constant as the descending drive from other systems such as the corticospinal tract increases to produce higher torque levels. Although statistical significance was not reached in the soleus, the maximum discharge rate increased in both muscles as the effort level increased. It is possible that the TA especially relies on increasing discharge rate to increase motor output from 10% to 30% effort level. The results after normalizing for the mean maximum discharge rate showed that the difference in discharge rate range was not the cause of difference in ∆F between the muscles. The rate-rate slopes were greater than 1 across all conditions, consistent with a previous study (Monster and Chan 1977), suggesting a greater distribution of synaptic input onto high versus low threshold units. In conclusion, the soleus and the TA exhibit a substantial magnitude of PICs, characterized as ΔF, during isometric force generation. Despite the findings in the upper limb and the soleus’ tonic EMG activity during postural control, the TA exhibits significantly higher ΔF. Although the data were taken from two different cohorts of participants, the same trend was observed in both sitting and standing conditions. In the future, the functional significance of the findings will be explored by directly comparing ∆F values during sitting and standing from the same cohort of participants.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01-NS-098509.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.H.K., J.M.W., and C.K.T. performed experiments; E.H.K. analyzed data; E.H.K. interpreted results of experiments; E.H.K. and C.K.T. prepared figures; E.H.K. drafted manuscript; E.H.K., J.M.W., C.K.T., and C.H. edited and revised manuscript; E.H.K., J.M.W., C.K.T., and C.H. approved final version of manuscript; J.M.W. and C.H. conceived and designed research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Randy Powers for providing vital recommendations on data analysis and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bennett DJ, Li Y, Harvey PJ, Gorassini M. Evidence for plateau potentials in tail motoneurons of awake chronic spinal rats with spasticity. J Neurophysiol 86: 1972–1982, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder MD, Heckman CJ, Powers RK. Relative strengths and distributions of different sources of synaptic input to the motoneurone pool: implications for motor unit recruitment. Adv Exp Med Biol 508: 207–212, 2002. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0713-0_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstone RM. Beginning at the end: repetitive firing properties in the final common pathway. Prog Neurobiol 78: 156–172, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchthal F, Schmalbruch H. Motor unit of mammalian muscle. Physiol Rev 60: 90–142, 1980. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Stein RB. Amplitude modulation of the soleus H-reflex in the human during walking and standing. J Neurosci 6: 1308–1313, 1986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-05-01308.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Stein RB. Difference in the amplitude of the human soleus H reflex during walking and running. J Physiol 392: 513–522, 1987. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins D, Gorassini M, Bennett D, Burke D, Gandevia S. Recent evidence for plateau potentials in human motoneurons. Adv Exp Med Biol 508: 227–235, 2002. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0713-0_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotel F, Antri M, Barthe JY, Orsal D. Identified ankle extensor and flexor motoneurons display different firing profiles in the neonatal rat. J Neurosci 29: 2748–2753, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3462-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JT, Lichtwark GA, Cresswell AG. Tibialis anterior muscle fascicle dynamics adequately represent postural sway during standing balance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 1742–1750, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00517.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragert K, Zehr EP. Rhythmic arm cycling modulates Hoffmann reflex excitability differentially in the ankle flexor and extensor muscles. Neurosci Lett 450: 235–238, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchateau J, Enoka RM. Human motor unit recordings: origins and insight into the integrated motor system. Brain Res 1409: 42–61, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edamura M, Yang JF, Stein RB. Factors that determine the magnitude and time course of human H-reflexes in locomotion. J Neurosci 11: 420–427, 1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00420.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eken T, Hultborn H, Kiehn O. Possible functions of transmitter-controlled plateau potentials in alpha motoneurones. Prog Brain Res 80: 257–267, 1989. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Negro F. Common synaptic input to motor neurons, motor unit synchronization, and force control. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 43: 23–33, 2015. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley RC, Kalmar JM. Estimates of persistent inward current in human motor neurons during postural sway. J Neurophysiol 122: 2095–2110, 2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.00254.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini M, Yang JF, Siu M, Bennett DJ. Intrinsic activation of human motoneurons: possible contribution to motor unit excitation. J Neurophysiol 87: 1850–1858, 2002a. doi: 10.1152/jn.00024.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini M, Yang JF, Siu M, Bennett DJ. Intrinsic activation of human motoneurons: reduction of motor unit recruitment thresholds by repeated contractions. J Neurophysiol 87: 1859–1866, 2002b. doi: 10.1152/jn.00025.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ, Yang JF. Self-sustained firing of human motor units. Neurosci Lett 247: 13–16, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini MA, Knash ME, Harvey PJ, Bennett DJ, Yang JF. Role of motoneurons in the generation of muscle spasms after spinal cord injury. Brain 127: 2247–2258, 2004. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosgnach S, Quevedo J, Fedirchuk B, McCrea DA. Depression of group Ia monosynaptic EPSPs in cat hindlimb motoneurones during fictive locomotion. J Physiol 526: 639–652, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AS, Kim EK, Khurram OK, Cummings M, Thompson CK, Miller-McPherson L, Heckman CJ, Dewald JP, Negro F. Properties of motor units of elbow and ankle muscles decomposed using high-density surface EMG. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2019: 3874–3878, 2019. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2019.8857475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Enoka RM. Motor unit. Compr Physiol 2: 2629–2682, 2012. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Johnson MD. Reconfiguration of the electrical properties of motoneurons to match the diverse demands of motor behavior. Adv Exp Med Biol 826: 33–40, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1338-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Mottram C, Quinlan K, Theiss R, Schuster J. Motoneuron excitability: the importance of neuromodulatory inputs. Clin Neurophysiol 120: 2040–2054, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herda TJ, Miller JD, Trevino MA, Mosier EM, Gallagher PM, Fry AC, Vardiman JP. The change in motor unit firing rates at de-recruitment relative to recruitment is correlated with type I myosin heavy chain isoform content of the vastus lateralis in vivo. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 216: 454–463, 2016. doi: 10.1111/apha.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Farina D, Gazzoni M, Merletti R, Zazula D. Estimating motor unit discharge patterns from high-density surface electromyogram. Clin Neurophysiol 120: 551–562, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.10.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Minetto MA, Botter A, Negro F, Farina D. Experimental analysis of accuracy in the identification of motor unit spike trains from high-density surface EMG. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 18: 221–229, 2010. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2010.2041593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J, Hultborn H, Jespersen B, Kiehn O. Bistability of alpha-motoneurones in the decerebrate cat and in the acute spinal cat after intravenous 5-hydroxytryptophan. J Physiol 405: 345–367, 1988. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD, Miller JF, Heckman CJ. Intrinsic electrical properties of spinal motoneurons vary with joint angle. Nat Neurosci 10: 363–369, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nn1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Polgar J, Weightman D, Appleton D. Data on the distribution of fibre types in thirty-six human muscles. An autopsy study. J Neurol Sci 18: 111–129, 1973. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(73)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Frigon A, Hurteau MF, Cain C, Heckman CJ. Reflex wind-up in early chronic spinal injury: plasticity of motor outputs. J Neurophysiol 117: 2065–2074, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00981.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Heckman CJ. Interactions between focused synaptic inputs and diffuse neuromodulation in the spinal cord. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1198: 35–41, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido A, Tanaka N, Stein RB. Spinal excitation and inhibition decrease as humans age. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 82: 238–248, 2004. doi: 10.1139/y04-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Eken T. Prolonged firing in motor units: evidence of plateau potentials in human motoneurons? J Neurophysiol 78: 3061–3068, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Erdal J, Eken T, Bruhn T. Selective depletion of spinal monoamines changes the rat soleus EMG from a tonic to a more phasic pattern. J Physiol 492: 173–184, 1996. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EH, Heckman CJ, Wilson JM. Comparison of the intrinsic excitability of human motoneurons in lower limb flexor and extensor muscles. Neuroscience 2017 Washington, DC, November 11–15, 2017, 781.04. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Enhancement of bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo by the noradrenergic alpha1 agonist methoxamine. J Neurophysiol 81: 2164–2174, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Adjustable amplification of synaptic input in the dendrites of spinal motoneurons in vivo. J Neurosci 20: 6734–6740, 2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06734.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mambrito B, De Luca CJ. A technique for the detection, decomposition and analysis of the EMG signal. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 58: 175–188, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratta R, Fenrich KK, Zhao E, Neuber-Hess MS, Rose PK. Distribution and density of contacts from noradrenergic and serotonergic boutons on the dendrites of neck flexor motoneurons in the adult cat. J Comp Neurol 523: 1701–1716, 2015. doi: 10.1002/cne.23765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill KC, Lateva ZC, Marateb HR. EMGLAB: an interactive EMG decomposition program. J Neurosci Methods 149: 121–133, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard A, Leblond H, Gossard JP. Modulation of monosynaptic transmission by presynaptic inhibition during fictive locomotion in the cat. Brain Res 964: 67–82, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)04067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monster AW, Chan H. Isometric force production by motor units of extensor digitorum communis muscle in man. J Neurophysiol 40: 1432–1443, 1977. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.6.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram CJ, Suresh NL, Heckman CJ, Gorassini MA, Rymer WZ. Origins of abnormal excitability in biceps brachii motoneurons of spastic-paretic stroke survivors. J Neurophysiol 102: 2026–2038, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00151.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muceli S, Poppendieck W, Negro F, Yoshida K, Hoffmann KP, Butler JE, Gandevia SC, Farina D. Accurate and representative decoding of the neural drive to muscles in humans with multi-channel intramuscular thin-film electrodes. J Physiol 593: 3789–3804, 2015. doi: 10.1113/JP270902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawab SH, Chang SS, De Luca CJ. High-yield decomposition of surface EMG signals. Clin Neurophysiol 121: 1602–1615, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro F, Muceli S, Castronovo AM, Holobar A, Farina D. Multi-channel intramuscular and surface EMG decomposition by convolutive blind source separation. J Neural Eng 13: 026027, 2016. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/2/026027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault MC, Shefchyk SJ, Jimenez I, McCrea DA. Depression of muscle and cutaneous afferent-evoked monosynaptic field potentials during fictive locomotion in the cat. J Physiol 521: 691–703, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Binder MD. Input-output functions of mammalian motoneurons. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 143: 137–263, 2001. doi: 10.1007/BFb0115594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Elbasiouny SM, Rymer WZ, Heckman CJ. Contribution of intrinsic properties and synaptic inputs to motoneuron discharge patterns: a simulation study. J Neurophysiol 107: 808–823, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00510.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Heckman CJ. Contribution of intrinsic motoneuron properties to discharge hysteresis and its estimation based on paired motor unit recordings: a simulation study. J Neurophysiol 114: 184–198, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00019.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RK, Nardelli P, Cope TC. Estimation of the contribution of intrinsic currents to motoneuron firing based on paired motoneuron discharge records in the decerebrate cat. J Neurophysiol 100: 292–303, 2008. doi: 10.1152/jn.90296.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather JF, Powers RK, Cope TC. Amplification and linear summation of synaptic effects on motoneuron firing rate. J Neurophysiol 85: 43–53, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill AL, Fuglevand AJ. Effects of persistent inward currents, accommodation, and adaptation on motor unit behavior: a simulation study. J Neurophysiol 106: 1467–1479, 2011. doi: 10.1152/jn.00419.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez N, Acosta AM, Stienen AH, Dewald JP. A multiple degree of freedom lower extremity isometric device to simultaneously quantify hip, knee, and ankle torques. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 23: 765–775, 2015. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2348801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkjaer T, Andersen JB, Ladouceur M, Christensen LO, Nielsen JB. Major role for sensory feedback in soleus EMG activity in the stance phase of walking in man. J Physiol 523: 817–827, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves JD, Jordan LM. Localization of a descending pathway in the spinal cord which is necessary for controlled treadmill locomotion. Neurosci Lett 20: 283–288, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson JL, Maluf KS. Dependence of the paired motor unit analysis on motor unit discharge characteristics in the human tibialis anterior muscle. J Neurosci Methods 198: 84–92, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udina E, D’Amico J, Bergquist AJ, Gorassini MA. Amphetamine increases persistent inward currents in human motoneurons estimated from paired motor-unit activity. J Neurophysiol 103: 1295–1303, 2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00734.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Thompson CK, Miller LC, Heckman CJ. Intrinsic excitability of human motoneurons in biceps brachii versus triceps brachii. J Neurophysiol 113: 3692–3699, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00960.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz US, Negro F, Diedrichs R, Farina D. Reciprocal inhibition between motor neurons of the tibialis anterior and triceps surae in humans. J Neurophysiol 119: 1699–1706, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00424.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz US, Negro F, Sebik O, Holobar A, Frömmel C, Türker KS, Farina D. Estimating reflex responses in large populations of motor units by decomposition of the high-density surface electromyogram. J Physiol 593: 4305–4318, 2015. doi: 10.1113/JP270635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]