Graphical abstract

Keywords: Virtual reality, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Proteins, Drug-design

Abstract

The era of the explosion of immersive technologies has bumped head-on with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The proper understanding of the three-dimensional structures that compose the virus, as well as of those involved in the infection process and in treatments, is expected to contribute to the advance of fundamental and applied research against this pandemic, including basic molecular biology studies and drug design. Virtual reality (VR) is a powerful technology to visualize the biomolecular structures that are currently being identified for SARS-CoV-2 infection, opening possibilities to significant advances in the understanding of the disease-associate mechanisms and thus to boost new therapies and treatments. The present availability of VR for a large variety of practical applications together with the increasingly easiness, quality and economic access of this technology is transforming the way we interact with digital information. Here, we review the software implementations currently available for VR visualization of SARS-CoV-2 molecular structures, covering a range of virtual environments: CAVEs, desktop software, and cell phone applications, all of them combined with head-mounted devices like cardboards, Oculus Rift or the HTC Vive. We aim to impulse and facilitate the use of these emerging technologies in research against COVID-19 trying to increase the knowledge and thus minimizing risks before placing huge amounts of money for the development of potential treatments.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic that has emerged towards the end of 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of the Chinese province of Hubei [1], [2]. Prior to SARS-CoV-2, six coronaviruses were known to cause diseases in humans, four of them causing only mild to moderate symptoms and other two (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) provoking severe respiratory syndromes [1]. A large and still growing number of symptoms were ascribed to COVID-19, the most evident shared with other coronavirus infections: fever (87.9%), cough (67.7%), fatigue (38.1%) and, to a less extent, diarrhea (3.7%) and vomiting (5.0%) [3]. However, in contrast with other coronaviruses, COVID-19 frequently exhibits unexpected long-term severe consequences.

Each SARS-CoV-2 virion is a 50–200 nm diameter spherical-like capsule enclosed by a protein-decorated lipid bilayer that contains a single-stranded RNA chain. Some of the proteins encrusted in this membrane are the receptors employed to anchor target cells [4]. Four structural proteins have been reported to form part of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2: S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane), and N (nucleocapsid) proteins [5]. The protruding part of the membrane embedded S-proteins recognize specific receptors in target cells, thus being key for the different stages of the infection mechanism: recognition, attachment of the virus and membrane fusion. The human angiotension-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was identified as the natural receptor of the virus although it has been reported that the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) could also play a significant role [6]. Once the virus enters the cell, an acute infection takes place.

A huge effort has been performed to obtain structural information with atomic resolution of this virus, aiming to understand its infection mechanism and then to develop effective drugs against it. The structures of several COVID-19 proteins are already publicly available and specific sites have been created to facilitate the access to the corresponding entries: see for instance PDBj [7], [8] or the Spanish 3DBIONOTES-COVID19 tool [9]. Both sites contain SARS-CoV-2 protein models from different sources: PDB-Redo, SwissProt, AlphaFold, European Projects and the repository of the Coronavirus Structural Taskforce. Visual and quantitative analysis of these molecules are expected to provide key structural, biological, and pharmacological insights to understand their function that would be hardly accessible by other methods.

The growing implementation of augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and mixed reality (MR) technologies for many applications in a large variety of fields together with the increasingly easiness, quality and economic access to these technologies is clearly transforming the way we interact with digital information by enriching classical methods of communicating information. Traditional flat pictures can now be easily complemented by adding new dimensions, user interaction, movement and even sound. Although these technologies have existed for decades, it has not been until very recently that they are being successfully exploited, favored by the democratization of the access to the required technologies due to the quick reduction of cost during the last years to and the accelerated enhance of the performance [10]. These technologies are transforming media and entertainment and have already impacted Chemistry and Biology in education, research and dissemination, in particular for molecular visualization, where they have an obvious potential [11]. The use and advantages of using VR during COVID-19 pandemic have been reviewed recently [12]. VR has proved to be useful in a large number of applications such as telemedicine, planning, patient treatment, medical marketing, training & learning, contributing to prevent infections by disseminating information, and even to reduce the face to face interaction of medical doctors with the infected COVID-19 patients. In the present work we will deal with a different and more specific application of VR technologies that is expected to have a large impact in research, education and dissemination of information related with this virus: the immersive visualization of SARS-CoV-2 proteins and receptors involved in their infection mechanism. Molecular structures are naturally tridimensional, flexible and they are rarely isolated. Remarkably, they are typically represented as flat sets of circles (atoms) joined by rigid bars (bonds). Such a representation is not realistic and makes difficult to understand how molecules behave. The ability to properly visualize from different perspectives as well as to manipulate virtual representations of chemical structures is key to understand complex molecules. Thus, VR technologies applied to molecular visualization facilitate rational drug design and, in general, the understanding of molecular mechanisms in life science research. Of course, the same arguments can also be extrapolated to the design of molecules for other (bio)technological purposes [13]. Standard software for the visualization of 3D molecular structures, such as VMD [14] or PyMol [15] significantly improve their comprehension by projecting them onto 2D screens, allowing users to examine them in an artificial 3D environment. However, there is a qualitative difference between this visual approach to three-dimensional structures and the immersive visualization, with no limitation in the translational and rotational perspectives of the observer and even with the possibility to interact with the target system, provided by VR. When applied to COVID-19, VR affords a clear advantage compared to more conventional molecular visualization / interactive technologies. For example, being able to view and interact with the molecules involved in the SARS-CoV-2 infection as three-dimensional objects simplifies the task of modifying them so they fit better to protein binding sites. VR interaction is the more intuitive way to deal with viral proteins, human receptors and possible drugs, realistically sensing their 3D structure and providing a perception that cannot be achieved with more conventional techniques.

Different headsets have been designed to facilitate the natural movement and interaction in such virtual environments, with the quality and performance to cost ratio quickly increasing with time. Immersive environments to visualize molecules have been working for more than 20 years for educational purposes, dissemination, research and structural analysis but the required infrastructure (Cave Automatic Virtual Environments or CAVEs) was accessible only throughout educational or research centers [16], [17]. In these old systems, the images projected on the walls and the floor of confined spaces of different geometries were viewed in three dimensions by using different complementary devices that included headsets and pointer-tracking systems. Molecular dynamics simulations of relatively complex systems could be viewed and analyzed in these environments. Several examples have been reported including drug-protein binding studies [18], [19], comparison between structures of related proteins [20], [21], interactive docking between proteins [22], examination of NMR ensembles and constrains [23], Caffeine computational simulations at quantum–classical levels [24], design and construction of nanotube models [25], and education in the characterization of drug-receptor interactions [26].

More recently, VR technology has been used to visualize specific molecules and even to interact with them in much more portable devices based on smartphones. VR-based learning tools such as NanoOne (by Nanome, http://nanome.ai) or Molecular Zoo have been developed for students to efficiently handle biomomolecules in an affordable way [27]. In the same line, Peppy is a VR tool aimed at facilitating the teaching of the principles of relatively short polypeptides structure to undergraduate classes [28]. From a complementary perspective with educational and research applications, David R. Glowacki et al. developed a framework for interactive molecular dynamics in a multiuser VR environment. This framework allows the synchronized visualization and the cooperative manipulation of complex molecular structures (fullerene, carbon nanotubes, etc) “on the fly” by several users in the same virtual environment [29], [30]. Finally, the MolDRIVE system, developed at the TU Delft [31], allows interactive molecular dynamic simulations with artificial forces applied by the user. This could be useful to reach specific configurations of the studied molecules or molecular systems. MolDRIVE can be used in a variety of VR systems such as workbenches and CUBEs but it is not designed for more affordable devices. The official website of this application (http://graphics.tudelft.nl/Projects/MolDrive) has not been available during the preparation of this manuscript. Although all the previous applications are very interesting to visualize other type of molecules, in this review we will focus just on VR software that allows the visualization of molecular structures involved in the infection caused by SARS-CoV-2.

2. Virtual reality in the molecular visualization of SARS-CoV-2

Next, we will examine different VR implementations that allow the visualization of publicly available molecular structures related to COVID-19. This revision will cover desktop applications, web-based VR implementations and downloadable apps for smartphones.

3. Desktop applications

A number of desktop applications enable VR molecular visualization in combination with high-end VR devices (Oculus Rift, HTC VIVE, and Microsoft Mixed Reality). They can be really helpful for expert/professional users, allowing visualization, analysis and interaction options. Typically, the installation and effective use of these programs are not as straightforward as for applications developed for smartphones since they often require external dependences and some training. Most of them are based on the Unity3D video game engine (https://unity.com/). In general, these applications are properly optimized and quite stable. The most popular desktop applications of this group are:

Molecular Rift [32], [33] is an open-source molecular viewer that allows the interaction with the VR environment throughout hand gestures instead of standard VR controllers. It is based on Unity3D combined with the UnityMol open-source library to visualize molecules in Unity3D [34]. UnityMol [34], [35] is a molecular viewer developed to work with the Unity3D (https://unity.com/) game engine. It incorporates code to identify secondary structure of proteins as well as different visualization formats and specific selections. It is based on the VRTK [36] framework to support HTC Vive, Oculus headsets, and Windows Mixed Reality. UCSF ChimeraX [27], [37] is also based on Unity3D. It is well suited for visualization and analysis of biomolecular structures (even multi-person VR sessions), especially proteins and nucleic acids, using virtual reality headsets such as HTC Vive, Vive Pro, Oculus Rift, Samsung Odyssey and Windows Mixed Reality. However, one of the main limitations of Chimera X to visualize structures from the SARS-CoV-2 is that large molecular structures (more than a few thousand atoms) render too slowly and cause stuttering in the headset [38]. VMD is a classical molecular viewer with a large number of interesting features along with VR capabilities that is compatible with a wide variety of devices including flat screens, 6-degree-of-freedom input gadgets, and haptics accessories [39]. A number of general purpose VR toolkits such as CAVElib, FreeVR, VRPN and VR Juggler are well suited to work with VMD [40], [41], [42], [43]. A freely available software pipeline to transform molecular structures from VMD to 3D objects in the VR environment, has been recently released [44]. More recently, a GPU-accelerated ray tracing engine, so called TachyonL-OptiX, aimed to obtain stereoscopic panoramic and omnidirectional projections compatible with VMD has been developed, allowing the visualization of large molecules with head-mounted displays, as the Oculus Rift or even Google Cardboard compatible [45]. An example can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QPIyk0V6F7A&list=PL8XC6Vx8S1GBT311VIFLt84iuSRhPuXAB&index=2. Nanosimbox Research, currently inactive, was a commercial platform developed in C# that allows using VR to change molecular aesthetics and snapshot molecular structures [46]. It required a VR-compatible laptop and the HTC Vive virtual reality headset. On the other hand, the open-source BlendMol [47] plugin, written in Python, allows producing high quality images of protein structures from imported PyMol and VMD visualization states using the Blender software (Fig. 1) [48]. Once the structures are imported, third-party plugins can be employed to export the models to VR compatible formats that then can be visualized using, for instance, the BabylonJS engine that uses Javascript libraries to show 3D graphs in a web browser through HTML5. The whole process is not straightforward but allows modifying and decorating the representation of the molecule by using the advanced functions of Blender. RealityConvert [49] can also be used to transform molecular representations to VR and AR compatible format. The process is partially automated throughout a web app but only small molecular representations of less than 200 particles can be processed without additional third-party software: PyMol [15], Blender [48], Open Babel [50] and Molconvert [51], what makes the process non-trivial. AltPDB protein-viewer provides an immersive VR environment to visualize and to analyze complex molecular structures in a collaborative way [27]. This software admits any model from the Protein Data Bank. The source code is available in a public repository (https://github.com/AltPDB) and it can be executed in Windows and iOS through a free AltspaceVR account (https://account.altvr.com), although during the preparation of the manuscript this option was not available. It was developed using Unity3D and it is compatible with HTC Vive, Oculus Rift, and Samsung Odyssey. The highest limitation of this software is that it requires a pre-generated model by using third-party tools. Thus, as in the case of RealityConvert, the process is not trivial. Additionally, this project has not been updated during the last 3 years and the dedicated workspace seems to be inactive (https://account.altvr.com/spaces/altpdb). The Samson Connect module enables VR support in the SAMSON commercial platform for simulation of nanosystems [52], allowing to perform interactive simulations, visualize large scale models containing hundreds of thousands of atoms, design new molecules, build nanotube junctions, etc., all in VR). It is developed in C++ for the Windows Mixed Reality headset. The commercial program Nanome (Nanome Inc.) [53], developed in Unity 2017.4.3f and C#, allows molecular manipulation (e.g., in silico mutagenesis) in addition to molecular visualization. It uses VR to visualize, measure, and analyze drug molecules as 3D structural images. A possible limitation for some applications of this software is that the VR molecular scenes created using the free version are public. The software is compatible with Oculus Rift, HTC VIVE, and Microsoft Mixed Reality. Nanome is currently being used against COVID-19 by enabling scientists to gain insights into the molecular mechanics of the virus. In a recent paper [54], Insilico Medicine (https://insilico.com/) and Nanome applied deep learning methods and VR visualization to design treatments for COVID-19 infection (Fig. 1). They used the protease of COVID-19, required for the replication of the virus, as a target to develop new drugs, and took advantage of the knowledge acquired by artificial intelligence methods to propose potential candidates. Nanome contributes to structure-based design by integrating a 3D virtual reality viewing experience with molecular interaction and manipulation in a collaborative environment, allowing the input from various experts to be incorporated in real-time. The real time collaborative analysis in VR between the Insilico Medicine and the Nanome teams can be seen in at https://bit.ly/ncov-vr. The interaction between the Remdesivir antiviral treatment for COVID-19 [55] and the coronavirus RNA polymerase protein has also been analyzed by using Nanome [56]. Nanome is currently participating in the Covid Moonshot initiative [57] to design inhibitors against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

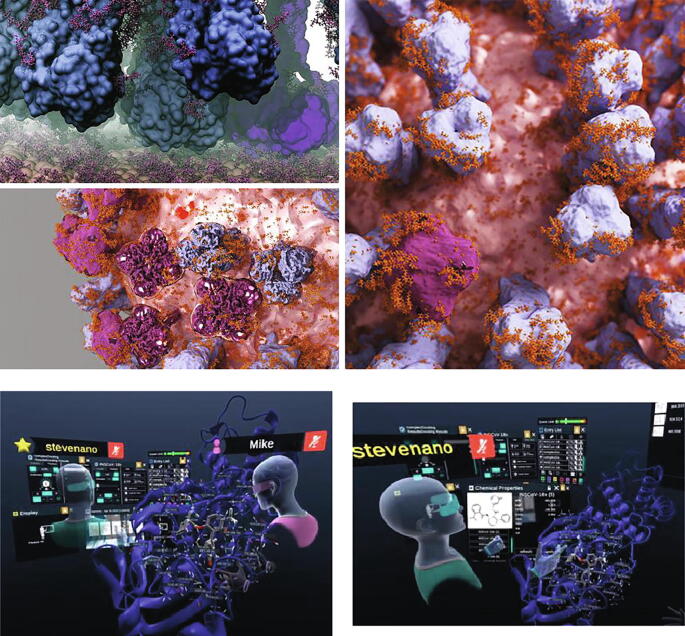

Fig. 1.

Snapshots of VR scenes including protein structures from the influenza virus or SARS-CoV-2, created using BlendMol [47], [58] (downloaded from https://git.durrantlab.pitt.edu/jdurrant/blendmol/-/tree/1_2/examples/web-files/virtual-reality, and carried out in Amaro Lab, UC San Diego) (top) and Nanome [53], [54] (bottom), respectively; Nanome images are obtained from Alex et al., 2020, under the license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

4. Web tools VR applications

In parallel to the advances in hardware, algorithms and software for visualization, it is possible to take advantage from internet to create VR scenes with protein and molecular structures, including those involved in SARS-CoV-2. Applications running from a server through a web browser exhibit two enormous advantages: (i) they are compatible with almost any operative system and device without special requirements or complementary software; and (ii) updates are instantaneous accessible to all the users. Using the Web Graphics Library (WebGL) [59], it is now possible to create web-based VR experiences that can be directly accessed with common web browsers. VRmol [60], is a molecular viewer with some analysis tools and a VR visualization mode (see Fig. 2). It is very well documented [61] and it is compatible with HTC, Vive, Oculus Rift, Microsoft Mix Reality and other VR devices that work with WebVR enabled web browsers (Microsoft Edge and Firefox Nightly, for instance). This application can read structures from different databases to facilitate drug design. ProteinVR [62], is a recently released 3D-VR molecular viewer that also works in modern web browsers without additional special requirements, as well as in a variety of electronic devices and VR headsets (see Fig. 2). It takes advantage of BabylonJS, an efficient alternative to Unity3D for this kind of applications (see description above). By using public URLs, collaborative work can also be done with ProteinVR. The code is available free of charge at http://durrantlab.com/protein-vr/, and it can be tested by using the following link: http://durrantlab.com/pvr/. Autodesk Molecular Viewer [63], is also a new web-based molecular viewer with VR capabilities and complementary analysis and edition tools that works in a large variety of devices. It allows visualizing very large molecular systems such as entire viruses. This program can generate input for different VR headsets just by accessing a shared URL. Unfortunately, the authors of this software decided to stop this project in 2018. Another web-based approach for online VR molecular-visualization systems that works also offline is iview [64]. Though a VR functionality is available in the software, we were not able to execute it. Additionally, the server where it is hosted seems to be unstable since we were not able to access during many of our tests. The group of Prof. Ricardo L. Mancera has recently developed a tool for the visualization of molecular dynamics simulations using a stereoscopic 3D Display [65]. Using the Unity game engine, and being developed in C#, this implementation allows a VR visualization of molecular dynamics trajectories carried out with different software (GROMACS, LAMMPS and NAMD) in a HIVE facility. Additionally, it is also possible to run the application on a Windows PC desktop for local demonstration and testing purposes. BioVR is a platform which allows the VR visualization of DNA, RNA and protein structures using Unity3D and C# using the Oculus Rift as headsets [66]. Finally, it is also worth to mention the AR and VR applications developed by EPAM Life Sciences (https://www.epam.com/our-work/videos/vr-ar-molecular-visualization-apps).

Fig. 2.

Snapshots of VR scenes including protein structures created using VRmol [60] (top) and ProteinVR [62] (bottom). The structures correspond to the SARS Spike Glycoprotein - human ACE2 complex (PDB ID: 6CS2) (left) and to the Dimeric DARPin A_angle_R5 complex with EpoR (PDB ID: 6MOJ) (right).

5. Downloadable apps for smartphones

VR applications for smartphones facilitates their use, mainly if they are compatible with cheap headset such as cardboards. On the other hand, this kind of applications are typically very intuitive since they take advantage of the device sensors to move and interact with the VR environment in a natural way. However, we were able to find only two applications able to visualize SARS-CoV-2 proteins. PROteinVR [67] allows the visualization of proteins from the PDB Data Bank directly in VR. It has been developed using the Unity3D engine. With a VR headset (Google Cardboard compatible) and an Android or iPhone cell phone, it is possible dive through the 3D chemical structures of proteins, including those important in COVID-19. Recently, we have developed a new app, Corona VRus Coaster, which allows sliding along the backbone of 22 protein structures from SARS-CoV-2, in its current version, as if they were a roller Coaster, providing unique perspectives of the protein (Fig. 3) [68]. The available structures in the current version are: 7BQY (COVID-19 main protease), 7BV1 (Cryo-EM structure of the apo nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex), 7BV2 (nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 complex bound to the template-primer RNA and triphosphate form of Remdesivir), 6WKP (RNA-binding domain of nucleocapsid phosphoprotein from SARS CoV-2), 6WLC (NSP15 Endoribonuclease from SARS CoV-2 in the Complex with Uridine-5′-Monophosphate), 6YB7 (SARS-CoV-2 main protease with unliganded active site), 6YHU (nsp7-nsp8 complex of SARS-CoV-2), 6YI3 (N-terminal RNA-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein), 6YLA (SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain in complex with CR3022 Fab), 6YM0 (SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain in complex with CR3022 Fab (crystal form 1), 6YOR (SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 protein in complex with CR3022 Fab), 6M0K (COVID-19 main protease in complex with an inhibitor 11b), 6M71 (SARS-Cov-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in complex with cofactors), 6W9C (papain-like protease of SARS CoV-2), 6W9Q (Peptide-bound SARS-CoV-2 Nsp9 RNA-replicase), 6W37 (SARS-CoV-2 ORF7A encoded accessory protein), 6W41 (SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain in complex with human antibody CR3022), 6WCF (ADP ribose phosphatase of NSP3 from SARS-CoV-2 in complex with MES), 6LZE (COVID-19 main protease in complex with an inhibitor 11a), 6WJI (C-terminal Dimerization Domain of Nucleocapsid Phosphoprotein from SARS-CoV-2), 6WIQ (co-factor complex of NSP7 and the C-terminal domain of NSP8 from SARS CoV-2) and 6WEY (SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 Macro X domain). The “PLAY” bottom starts the navigation mode. By clicking on the “PAUSE” bottom the navigation stops in the current residue and the camera may be rotated, allowing a 360° view of the protein from that point. It works for android and iOS devices and it does not require the installation of additional programs or libraries. The application is freely available from http://mduse.com/coronavruscoaster/. Periodic updates will be avialable at the same url address.

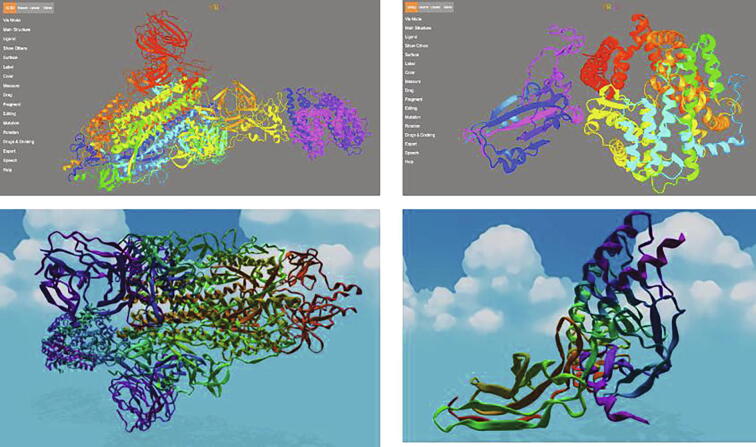

Fig. 3.

Snapshots of several SARS-CoV-2 molecular structures visualized with Corona VRus Coaster. This app, developed in our group [68], allows the visualization of several proteins involved in COVID-19, allowing also navigating throughout their backbone as if they were a roller coaster, providing unique perspectives.

6. Summary and outlook

In order to understand and develop effective treatments against SARS-CoV-2, responsible for global pandemic we are currently living, a deep knowledge of the molecular structures involved in the infection process is key. Virtual reality (VR) is a powerful tool for studying biomolecular structures, enabling their visualization in stereoscopic 3D. In this review, we have tried to gather and quickly describe the available VR tools enabling the visualization of the known molecular structures involved in COVID-19. The aim is to improve the understanding of the virus action mechanism as well as to contribute to accelerate the drug discovery process. We have examined the different implementations existent for VR, considering the complexity of the required infrastructure: Cave virtual environments, flat screens combined with specific headsets (Oculus Rift or HTC Vive), and extremely simple solutions such as Google Cardboard. Whereas the desktop applications allow the user to have a much more complete structural analysis, (i. e. Molecular Rift, UnityMol, Nanome, etc) such tools usually require the use of specific and not so affordable hardware. In contrast, web-based implementations are immediately accessible on a broad range of desktops, laptops, and mobile devices, without requiring the installation of any third-party programs or plugins. In turn, these applications typically loose functionality in structural analysis of the biomolecular structures (i. e. ProteinVR, VRmol, etc). Smartphone apps are still scarce (PROTeinVR and Corona VRus Coaster) but its development is expected to advance in giant steps at the short term. VR has been touted as a drug development tool for two decades but dismissed by some scientists as little more than a toy for looking at molecules and proteins, not a genuine research or education tool. However, the maturation of VR together with the increasingly easiness, quality and economic access of this technology is transforming the scope this technology can have in drug design and understanding of diseases. Despite the fact that further development is encouraged both in the number and in the usability of new VR applications that allow the visualization and manipulation of large biomolecules, the existing tools already urge their introduction into the conventional drug development processes addressed to COVID-19.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Martín Calvelo: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Ángel Piñeiro: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Rebeca Garcia-Fandino: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and the ERDF (RTI2018-098795-A-I00) by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2019-111327 GB-I00), Xunta de Galicia (Centro singular de investigación de Galicia accreditation 2019-2022, ED431G 2019/03), FCT- Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal, POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030579) and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund - ERDF). R.G.-F. thanks to Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades for a “Ramón y Cajal” contract (RYC-2016-20335). M.C. thanks to Xunta de Galicia for a predoctoral fellowship (ED481A-2017/068).

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P, Yang X Lou, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270–3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changeux J., Amoura Z., Rey F., Miyara M. A nicotinic hypothesis for Covid-19 with preventive and therapeutic implications. Qeios. 2020 doi: 10.5802/crbiol.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinjo A.R., Bekker G.-J., Suzuki H., Tsuchiya Y., Kawabata T., Ikegawa Y. Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj): updated user interfaces, resource description framework, analysis tools for large structures. Nucl Acids Res. 2016;45:D282–D288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinjo A.R., Bekker G.-J., Wako H., Endo S., Tsuchiya Y., Sato H. New tools and functions in data-out activities at Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj) Protein Sci. 2018;27:95–102. doi: 10.1002/pro.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segura J, Sanchez-Garcia R, Sorzano COS, Carazo JM. 3DBIONOTES v3.0: crossing molecular and structural biology data with genomic variations. Bioinformatics 2019;35:3512–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Oigara JN. Integrating virtual reality tools into classroom instruction. Handb. Res. Mob. Technol. Constr. meaningful Learn., IGI Global; 2018, p. 147–59.

- 11.Liu XH, Wang T, Lin JP, Wu M Bin. Using virtual reality for drug discovery: a promising new outlet for novel leads. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2018;13:1103–14. 10.1080/17460441.2018.1546286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Singh R.P., Javaid M., Kataria R., Tyagi M., Haleem A., Suman R. Significant applications of virtual reality for COVID-19 pandemic. DiabetesMetab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:661–664. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X.H., Wang T., Lin J.P., Bin WuM. Using virtual reality for drug discovery: a promising new outlet for novel leads. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2018 doi: 10.1080/17460441.2018.1546286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(27–28):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pymol DeLanoW.L. An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl Protein Crystallogr. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz-Neira C., Sandin D.J., DeFanti T.A., Kenyon R.V., Hart J.C. The CAVE: audio visual experience automatic virtual environment. Commun ACM. 1992;35:64–72. doi: 10.1145/129888.129892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Febretti A, Nishimoto A, Thigpen T, Talandis J, Long L, Pirtle JD, et al. CAVE2: a hybrid reality environment for immersive simulation and information analysis. In: Dolinsky M, McDowall IE, editors. Eng. Real. Virtual Real. 2013, vol. 8649, SPIE; 2013, p. 864903. 10.1117/12.2005484. [DOI]

- 18.Ai Z., Frohlich T. Molecular dynamics simulation in virtual environments. Comput Graph Forum. 1998;17:267–273. doi: 10.1111/1467-8659.00273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson A., Weng Z. VRDD: Applying virtual reality visualization to protein docking and design. J Mol Graph Model. 1999;17:180–186. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(99)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moritz E, Meyer J. Interactive 3D protein structure visualization using virtual reality. In: Proc. - Fourth IEEE Symp. Bioinforma. Bioeng. BIBE 2004, 2004, p. 503–7. 10.1109/BIBE.2004.1317384. [DOI]

- 21.Schulze J.P., Kim H.S., Weber P., Prudhomme A., Bohn R.E., Seracini M. Advanced applications of virtual reality 1 introduction. Adv Comput. 2011;82:218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Férey N., Nelson J., Martin C., Picinali L., Bouyer G., Tek A. Multisensory VR interaction for protein-docking in the CoRSAIRe project. Multisen-sory VR interaction for protein-docking in the CoRSAIRe Multisensory VR interaction for Protein-Docking in the CoRSAIRe project. Virtual Real. 2009;13:273–293. doi: 10.1007/s10055-009-0136-zï. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Block J.N., Zielinski D.J., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Claire E.C., Brady R. KinImmerse: macromolecular VR for NMR ensembles. Source Code Biol Med. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salvadori A., Del Frate G., Pagliai M., Mancini G., Barone V. Immersive virtual reality in computational chemistry: applications to the analysis of QM and MM data. Int J Quantum Chem. 2016;116:1731–1746. doi: 10.1002/qua.25207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doblack B.N., Allis T., Dávila L.P. Novel 3D/VR interactive environment for MD simulations, visualization and analysis. J Vis Exp. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson A., Bracegirdle L., McLachlan S.I.H., Chapman S.R. Use of a three-dimensional virtual environment to teach drug-receptor interactions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goddard T.D., Brilliant A.A., Skillman T.L., Vergenz S., Tyrwhitt-Drake J., Meng E.C. Molecular visualization on the holodeck. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:3982–3996. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doak D.G., Denyer G.S., Gerrard J.A., Mackay J.P., Peppy AllisonJ.R. A Virtual reality environment for exploring the principles of polypeptide structure. BioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/723155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor M., Deeks H.M., Dawn E., Metatla O., Roudaut A., Sutton M. Sampling molecular conformations and dynamics in a multiuser virtual reality framework. Sci Adv. 2018 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor MB, Bennie SJ, Deeks HM, Jamieson-Binnie A, Jones AJ, Shannon RJ, et al. Interactive molecular dynamics in virtual reality from quantum chemistry to drug binding: An open-source multi-person framework. J Chem Phys 2019;150. 10.1063/1.5092590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Computer Graphics and Visualization | TU Delft n.d. https://graphics.tudelft.nl/ (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 32.Norrby M., Grebner C., Eriksson J., Boström J. Molecular rift: virtual reality for drug designers. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:2475–2484. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grebner C., Norrby M., Enström J., Nilsson I., Hogner A., Henriksson J. 3D-Lab: a collaborative web-based platform for molecular modeling. Future. Med Chem. 2016 doi: 10.4155/fmc-2016-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv Z., Tek A., Da Silva F., Empereur-mot C., Chavent M., Baaden M. Game on, science – how video game technology may help biologists tackle visualization challenges. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pérez S., Tubiana T., Imberty A., Baaden M. Three-dimensional representations of complex carbohydrates and polysaccharides—SweetUnityMol: a video game-based computer graphic software. Glycobiology. 2014;25:483–491. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.VRTK - Virtual Reality Toolkit n.d. https://vrtoolkit.readme.io/ (accessed June 20, 2020).

- 37.Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Meng E.C., Pettersen E.F., Couch G.S., Morris J.H. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018;27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ChimeraX Virtual Reality n.d. https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/docs/user/vr.html (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 39.Stone JE, Kohlmeyer A, Vandivort KL, Schulten K. Immersive Molecular Visualization and Interactive Modeling with Commodity Hardware - Advances in Visual Computing. In: Bebis G, Boyle R, Parvin B, Koracin D, Chung R, Hammound R, et al., editors., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010, p. 382–93.

- 40.Cruz-Neira C, Sandin DJ, DeFanti TA. Surround-screen projection-based virtual reality: The design and implementation of the CAVE. Proc. 20th Annu. Conf. Comput. Graph. Interact. Tech. SIGGRAPH 1993, New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc; 1993, p. 135–42. 10.1145/166117.166134. [DOI]

- 41.Pape D, Anstey J, Sherman B. Commodity-based projection VR. ACM SIGGRAPH 2004 Course Notes, SIGGRAPH 2004, New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc; 2004, p. 19-es. 10.1145/1103900.1103919. [DOI]

- 42.Taylor RM, Hudson TC, Seeger A, Weber H, Juliano J, Helser AT. VRPN: a device-independent, network-transparent VR peripheral system. In: Proc. ACM Symp. Virtual Real. Softw. Technol. – VRST ’01, New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2001, p. 55. 10.1145/505008.505019. [DOI]

- 43.Bierbaum A., Just C., Hartling P., Meinert K., Baker A., Cruz-Neira C. VR Juggler: a virtual platform for virtual reality application development. Proc IEEE Virtual Real. 2001;2001:89–96. doi: 10.1109/VR.2001.913774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ratamero E.M., Bellini D., Dowson C.G., Römer R.A. Touching proteins with virtual bare hands: Visualizing protein–drug complexes and their dynamics in self-made virtual reality using gaming hardware. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2018;32:703–709. doi: 10.1007/s10822-018-0123-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone J.E., Sener M., Vandivort K.L., Barragan A., Singharoy A., Teo I. Atomic detail visualization of photosynthetic membranes with GPU-accelerated ray tracing. Parallel Comput. 2016;55:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.parco.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Connor M, Tew P, Sage B, McIntosh-Smith S, Glowacki DR. Nano simbox: An OpenCL-accelerated framework for interactive molecular dynamics. In: ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser., vol. 12-13- May-2015, New York, New York, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2015, p. 1–1. 10.1145/2791321.2791341. [DOI]

- 47.Durrant J.D. BlendMol: advanced macromolecular visualization in Blender. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:2323–2325. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kent BR. 3D Scientific Visualization with Blender® 2015. 10.1088/978-1-6270-5612-0. [DOI]

- 49.Borrel A., Fourches D. RealityConvert: a tool for preparing 3D models of biochemical structures for augmented and virtual reality. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3816–3818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A., Morley C., Vandermeersch T., Hutchison G.R. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.[51] Marvin | ChemAxon n.d. https://chemaxon.com/products/marvin (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 52.SAMSON Connect|Elements|Virtual Reality Portal n.d. https://www.samson-connect.net/element/64225415-0c58-6ef2-4b29-f6e78a01e460.html (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 53.Kingsley L.J., Brunet V., Lelais G., McCloskey S., Milliken K., Leija E. Development of a virtual reality platform for effective communication of structural data in drug discovery. J Mol Graph Model. 2019;89:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alex Z., Bogdan Z., Alexander Z., Vladimir A., Victor T., Quentin V. Potential Non-Covalent SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitors designed using generative deep learning approaches and reviewed by human medicinal chemist in virtual reality. ChemRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin W, Mao C, Luan X, Shen D-D, Shen Q, Su H, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. Science (80-) 2020:eabc1560. 10.1126/science.abc1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.How Remdesivir interacts with the Coronavirus RNA Polymerase protein - YouTube n.d. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5a8FrFRqZqM (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 57.PostEra | COVID-19 n.d. https://covid.postera.ai/covid (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 58.examples/web-files/virtual-reality · 1_2 · jdurrant / blendmol · GitLab n.d. https://git.durrantlab.pitt.edu/jdurrant/blendmol/-/tree/1_2/examples/web-files/virtual-reality (accessed June 22, 2020).

- 59.Khronos Releases Final WebGL 1.0 Specification - The Khronos Group Inc n.d. https://www.khronos.org/news/press/khronos-releases-final-webgl-1.0-specification (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 60.Xu K., Liu N., Xu J., Guo C., Zhao L., Wang H. VRmol: an integrative cloud-based virtual reality system to explore macromolecular structure. BioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/589366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tutorial for VRmol -- an Integrative Cloud-Based Virtual Reality System to Explore Macromolecular Structure n.d. https://vrmol.net/docs/ (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 62.Cassidy K.C., Šefčík J., Raghav Y., Chang A., Durrant J.D. ProteinVR: Web-based molecular visualization in virtual reality. PLOS Comput Biol. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balo A.R., Wang M., Ernst O.P. Accessible virtual reality of biomolecular structural models using the Autodesk Molecule Viewer. Nat Methods. 2017;14:1122–1123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H., Leung K.-S., Nakane T., Wong M.-H. iview: an interactive WebGL visualizer for protein-ligand complex. BMC Bioinf. 2014;15:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiebrands M, Malajczuk CJ, Woods AJ, Rohl AL, Mancera RL. Molecular Dynamics Visualization (MDV): stereoscopic 3D Display of Biomolecular Structure and Interactions Using the Unity Game Engine. J Integr Bioinform 2018;15:20180010. 10.1515/jib-2018-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Zhang J.F., Paciorkowski A.R., Craig P.A., Cui F. BioVR: a platform for virtual reality assisted biological data integration and visualization. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20:78. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.PROteinVR n.d. https://www.appmindedapps.com/proteinvr.html (accessed June 19, 2020).

- 68.Calvelo M, Porto C, Piñeiro Á, Garcia‐Fandino R. Corona VRus coaster: the virtual reality roller coaster of the proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Santiago de Compostela, Spain: 2020.