Introduction

Primary social groups such as family and peers, and their associated informal support networks, are important resources in the lives of adolescents. One important but under-researched source of informal social support is church-based social networks. Church-based social networks can provide youth with tangible and psychosocial resources (e.g., information, services, emotional support) for coping with life challenges. Support from church members has been shown to promote adolescent thriving (Gooden & McMahon, 2016) and self-esteem (Maton, Corns, Vieira-Baker, Lavine, Gouze, & Keating, 1996). Adolescents’ involvement in church-based social support networks is important for the development of prosocial traits and orientations including empathy and perspective-taking, mutuality, interpersonal trust, and responsibility (Smith, 2003). Finally, involvement in church-based networks allow adolescents opportunities for social skills development and direct role modeling of supportive behaviors (Ellison & Levin, 1998).

Church support networks may be particularly important for African American adolescents. This is due to both the higher levels of religious participation among African American adolescents in comparison to white adolescents (Smith, Denton, Faris, & Regnerus, 2002), as well as the historical importance of churches in black communities. For instance, religion and faith communities have historically performed important roles in promoting the health and well-being of Black Americans and in the development of Black communities (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990; Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004). Formally organized initiatives and informal social support networks operating within faith settings provide a broad range of activities and resources (e.g., educational, political, health and cultural) for children and youth, older adults, and families (Levin & Chatters, & Taylor, 2005; Taylor, Chatters & Levin, 2004).

Research examining the sociodemographic correlates of church-based social support can address basic and important questions regarding which adolescents participate in these exchanges and whether sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., family income) make a difference in the types of assistance they receive and provide to others. However, because research focuses on adults and the elderly (Krause, 2008; Taylor et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2017), we know very little about adolescents’ involvement in church-based support networks and the sociodemographic factors associated with support exchanges. The present study addresses this gap in the literature by exploring church-based social support within a national sample of African American and Black Caribbean adolescents (aged 13–17 years). The focus on both African American and Black Caribbean adolescents permits the exploration of potential ethnic differences in church support and its correlates among Black adolescents. Further, this analysis not only investigates the degree to which adolescents receive support it also examines the correlates of providing assistance to their church support networks. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the correlates of the provision and receipt of church-based support among African American or Black Caribbean adolescents.

The literature review begins with a discussion of the importance of examining ethnic variation within the Black population. This is followed by a discussion of theoretical perspectives on social networks and social support in relation to churches. Available research on religious participation and church involvement within African American and Black Caribbean populations is then presented, including demographic factors that are associated with both providing and receiving support from church members. Due to the lack of information on Black adolescents, we review findings from studies of church-based support networks among African American and Black Caribbean adults. The section concludes with a statement of the purpose of the study and hypotheses.

Ethnic Variation within the Black U.S. Population

Social science research has, in large part, ignored questions of ethnic variation within the Black population. As a result, studies routinely fail to account for ethnic and cultural differences between African Americans who were born in the U.S. and Black Caribbean immigrants who were born abroad (1st generation) or to immigrant parents in the U.S. (2nd generation). Due to a shared racial classification (as ‘Black’), Black Caribbeans and African Americans are treated in similar ways and experience comparable life situations and social status (Goosby et al. 2012; Seaton et al. 2008; Taylor & Chatters, 2011; Waters,1999). Nonetheless, significant differences in terms of cultures, histories, countries of origin, and religious traditions and institutions argue for examining whether and how ethnicity is associated with church-based support and its correlates.

Social Support and Social Networks

Research on church social networks and support exchanges builds upon a long tradition of work examining the demographic and social correlates of social networks and their supportive functions (Berkman & Glass, 2000). Central to these frameworks is the recognition that social networks themselves are embedded within and shaped by a broader social context that influences their form and function. For example, historically, Black religious institutions’ emphasis on social supports, mutual assistance, and the development and maintenance of the community emerged, in part, as a response to the oppressive broader social context in which they were situated. Social networks themselves have distinctive structural (e.g., size, duration) and compositional features, as well as norms and rules that govern their operation. Compositionally, religious networks are unique among social networks in that they are comprised of members who typically share a very high degree of similarity (homogeneity) with respect to social characteristics and shared worldviews and orientations. Further, membership in a religious setting typically endures over an extended period of time, often over several generations in a family (Taylor & Chatters, 1988).

Norms for social relationships include reciprocity in support exchanges, social cohesion, and expected levels of contact and organizational investment and participation in the network. Social networks can be a direct source of various types of support (e.g., instrumental assistance, advice and encouragement, financial aid, appraisal) which represents one of their central functions. Social networks can also influence (through direct instruction or social modeling) members’ behaviors in ways that constrain or enable particular actions and establish and reinforce accepted behavioral norms. Finally, interactions within networks can affect psychosocial states and processes such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, and coping. All of these attributes and traits are evident within social networks within religious institutions (Ellison & Levin, 1998). Given that many Black adolescents spend a significant portion of their lives in faith settings, they represent dynamic and unique environments for psychological and social development.

African America adolescents rank faith higher in importance than their counterparts in other racial groups (Donahue, 1995; Smith et al., 2003) and attend church more frequently (Smith, Denton, Faris, & Regnerus, 2002). Further, they participate in youth-oriented programs provided by Black churches (Rubin, Billingsley, & Caldwell, 2004; Ball, Armistead, & Austin, 2003; Barnes, 2015). For both African American and Black Caribbean adolescents, the role of churches often extends beyond religious formation and organizational religious involvement. Churches have been shown to function protectively across a wide range of health outcomes for Black youth (Butler-Barnes, Martin, Copeland-Linder, Seaton, Matusko, Caldwell, & Jackson, 2016; Cole-Lewis, Gipson, Opperman, Arango, & King, 2016; Johnson, Jang, De Li, & Larson, 2000; Steinman & Zimmerman, 2004; McCree, Wingood, Davies, & Harrington, 2003). One specific way that church functions protectively for Black adolescents is through church support (Hope et al., 2017). However, research has not identified the correlates and mechanisms of this support.

African Americans, Black Caribbeans and Church Networks

Given the important historic position of African American faith communities, they are regarded as valued and trusted institution and pivotal partner in advocating and promoting personal and community health and well-being. Church-based support networks are an enduring and indispensable part of this social mission, providing tangible, psychosocial, and civic assistance to church members. Church support, because it occurs within a religious context imbued with specific values, beliefs and norms, is regarded as distinctive and complementary to assistance provided by family (Chatters, Nguyen, Taylor, & Hope, 2018; Taylor et al., 2013). Roughly two-thirds of African American adults report that they receive support from church members on a frequent basis in the form of counseling and advice, emotional support, services, help when ill, prayers, financial aid, and information (Taylor et al., 2004).

Black Caribbean religious institutions share similar attributes and supportive functions found in African American churches. Black Caribbean churches have been important resources for new immigrants and subsequent generations and have played a prominent role in Black Caribbean life (Waters, 1999). Black Caribbean churches are often ethnically rooted with congregations that are composed exclusively of Black Caribbeans or individuals from a specific Caribbean country, thereby providing continuing connections to culture and traditions from countries of origin. Functionally, Black Caribbean churches provide spiritual and emotional support, tangible services, and social assistance to congregation members. Churches often offer church programs and cultural activities that reinforce ethnic ties and foster social connections relationships with other immigrants.

Adolescents and Church Support Networks

Church support networks may be particularly important for African American and Black Caribbean adolescents. Research has shown that African American youth have higher rates of service attendance and religious participation than their white counterparts (Donahue, 1995; Smith et al., 2002; Chatters et al., 1999). As noted earlier, for many immigrant communities, religious congregations play a critical role in helping families adjust to living in the United States and they are a primary means of building a community with other immigrants from their country of origin (Nguyen et al., 2016). As such, Black Caribbean adolescents may participate in religious communities that incorporate cultural connections as a part of their worship and programming. To date, however, there are no investigations of the correlates of involvement in church support networks among African American or Black Caribbean adolescents. There have been some examinations of the impact of church support networks on various psychological outcomes, but the contributions and mechanisms of church support for Black adolescents have not been explored. The limited amount of research has found that for African American youth, church based social support promotes thriving (Gooden & McMahon, 2016) and self-esteem (Maton, Corns, Vieira-Baker, Lavine, Gouze, & Keating, 1996). Church support has also been a significant protective factor for mental health among both African American and Black Caribbean adolescents who report experiencing discrimination (Hope, Assari, Cole-Lewis, & Caldwell, 2017).

Focus of the Present Study

The current study addresses gaps in the literature concerning church-based support among Black adolescents, as well as ethnic variation in church support among African American and Black Caribbean adolescents (ages 13–17 years). Accordingly, a reasonable first step is to examine the prevalence of church-based social support networks and explore their sociodemographic and church involvement correlates among diverse samples of Black adolescents. Given the lack of prior studies for this group, study hypotheses for relationships are based on research derived from adult samples.

With respect to ethnic differences, we anticipate that African American and Black Caribbean adolescents will demonstrate similar levels of receiving and providing social support (no differences by ethnicity). For both adolescent groups, we anticipate that younger age will be associated with receiving support more frequently, while older age will be associated with providing support to others more frequently. Similarly, we anticipate that girls will be the recipients and providers of support to a greater degree than boys. Lower levels of household income will be associated with receiving financial assistance more frequently; household income will be unrelated to providing help to others. Research on regional differences among African Americans indicates that Southern residents are more likely to be involved in religious pursuits, including church-based social support. For Black Caribbean adolescents, no predictions are presented for either regional or country of origin differences. For both groups of adolescents, frequency of service attendance and frequency of participation in congregational activities will be positively associated with receiving and providing support.

Method

Participants

This study utilizes data from National Survey of American Life-Adolescent (NSAL-A). The NSAL-A is a supplemental study of adolescents who were attached to adult households from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). The NSAL-A includes 1,170 adolescent respondents: 810 African American and 360 Black Caribbean. It is important to note that consistent with research in this field, in the NSAL-A the church support network questions were asked of only adolescents who indicated that they attend religious services at least a few times a year (Chatters et al., 2018; Krause, 2006). Consequently, the analytic sample for this study is African American (n= 726) and Black Caribbeans (n=316) who attend religious services at least a few times a year.

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Average age for both African American and Black Caribbean adolescents is 15 years (SD=1.62 and SD=0.59, respectively). African American adolescents are evenly split between male and female participants, while girls make up a majority (59%) of Black Caribbean adolescents. Family incomes were slightly lower for African American households, with annual reported incomes of $39,547 (SD=55,1800) and $40,085 (SD=13,319) for Black Caribbean households. Most African American youth reside in the South (61.8%), with 13.4% in the Northeast, 15.7% in the North Central, and 9.1% in the West. Among Black Caribbeans 65.90% reside in the Northeast and 34.10% reside in other regions, mostly the South. This regional distribution is consistent with census data for this population (Logan, 2007). Lastly, there were more than 25 countries of origin for Caribbean adolescents. The majority were from Jamaica (26.88%), followed by Haiti (14.09%), Trinidad-Tobago (13.88%), and other countries (45.15%) (e.g., Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, St. Lucia, Martinique).

Table 1.

Distribution of Demographic and Church Support Variablesa

| Demographic Variables | African Americans | Black Caribbeans | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 14.93 | 726 | 15.27 | 316 |

| S.D. | 1.62 | 0.59 | ||

| Income | ||||

| Mean | 39547.61 | 723 | 40085.70 | 313 |

| S.D. | 55180.60 | 13319.73 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 49.48 | 350 | 40.96 | 139 |

| Female | 50.52 | 376 | 59.04 | 177 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 13.35 | 72 | 65.90 | 216 |

| North Central | 15.72 | 87 | -- | |

| South | 61.82 | 523 | -- | |

| West | 9.10 | 43 | -- | |

| Other | -- | 34.10 | 97 | |

| Families Country of Origin | ||||

| Jamaica | -- | 26.88 | 86 | |

| Haiti | -- | 14.09 | 78 | |

| Trinidad-Tobago | -- | 13.88 | 39 | |

| Other | -- | 45.15 | 106 | |

| Frequency of Service Attendance | ||||

| Mean | 2.40 | 726 | 2.21 | 313 |

| S.D. | 1.03 | 0.43 | ||

| Participation in Congregational Activities | ||||

| Mean | 2.64 | 726 | 2.35 | 313 |

| S.D. | 1.35 | 0.54 | ||

| Frequency of Receiving Overall Assistance | ||||

| % Very Often/Fairly Often | 69.84 | 64.24 | ||

| Mean | 2.93 | 683 | 2.82 | 288 |

| S.D. | 1.15 | 0.47 | ||

| Frequency of Receiving Financial Assistance | ||||

| % Very Often/Fairly Often | 39.78 | 29.22 | ||

| Mean | 2.14 | 636 | 1.90 | 243 |

| S.D. | 1.30 | 0.48 | ||

| Frequency of Receiving Emotional Support | ||||

| Mean | 8.98 | 724 | 8.88 | 313 |

| S.D. | 2.76 | 1.08 | ||

| Frequency of Providing Overall Assistance | ||||

| % Very Often/Fairly Often | 59.48 | 52.17 | ||

| Mean | 2.66 | 691 | 2.49 | 299 |

| S.D. | 1.10 | 0.44 | ||

| Frequency of Providing Chores | ||||

| % Very Often/Fairly Often | 42.92 | 35.74 | ||

| Mean | 2.28 | 664 | 2.11 | 263 |

| S.D. | 1.25 | 0.47 | ||

| Frequency of Providing Help During Illness | ||||

| % Very Often/Fairly Often | 47.23 | 40.77 | ||

| Mean | 2.33 | 667 | 2.31 | 260 |

| S.D. | 1.25 | 0.50 | ||

Percents are weighted; frequencies are unweighted.

Procedure

The National Survey of American Life-Adolescent (NSAL-A) was conducted by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research and is a stratified, multistage area probability sample of African American, Black Caribbean, and non-Hispanic White adults. Data collection for the NSAL was conducted from February 2001 to June 2003, resulting in a total of 6,082 interviews with persons aged 18 or older (3,570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic whites, and 1,621 Black Caribbeans). The NSAL includes the first national probability sample of Black Caribbeans. For the purposes of this study, Black Caribbeans are defined as persons who trace their ethnic heritage to a Caribbean country, but who now reside in the United States, are racially classified as Black, and who are English-speaking (but may also speak another language). In both the African American and Black Caribbean samples, it was necessary for respondents to self-identify their race as Black. Those self-identifying as Black were included in the Black Caribbean sample if they: 1) answered affirmatively when asked if they were of West Indian or Caribbean descent, b) said they were from a country included on a list of Caribbean area countries presented by the interviewers, or c) indicated that their parents or grandparents were born in a Caribbean area country. African American ancestry was defined as individuals who self-identified as Black but who did not identify ancestral ties to the Caribbean (see Jackson et al., 2004, for more detailed information about the NSAL).

The adolescent sample of the NSAL was drawn exclusively from African American and Caribbean Black households. Every household that included an adult participant in the NSAL was screened for an eligible adolescent living in the household and adolescents were selected using a randomized procedure. If more than one adolescent in the household was eligible, up to two adolescents were selected for the study, and when possible, the second adolescent was of a different gender (Seaton et al., 2008). This resulted in non-independence in some households. Consequently, the NSAL-A was weighted to adjust for non-independence of selection within households, as well as non-response rates across households and individuals. The weighted data were post-stratified to approximate the national population distributions for gender (males and females) and age (13, 14, 15, 16, and 17) subgroups among African American and Caribbean Black youth. The weighting process allows us to make accurate inferences about the national population of African American and Black Caribbean youth (Seaton et al., 2008).

The majority of the adolescent interviews were conducted face to face using a computer-assisted instrument in their homes, but about 18% were conducted either entirely or partially by telephone. The overall response rate was 80.6% (80.4% for African Americans and 83.5% for Black Caribbeans). Respondents were compensated for their time. Data collection for the NSAL Adolescent Supplement were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and it is available through the Inter-University Consortium of Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan (see Seaton et al., 2008 for a more detailed information about the NSAL-A).

Measures

Dependent Variables

Six dependent variables were used in this analysis; three variables assess how often respondents received support from the members of their congregations and three assess how often respondents provided support.

Receiving support.

Adolescents were asked the frequency with which they received overall assistance, financial assistance, and emotional help. Overall assistance was measured by the question: “How often do people in your place of worship help you out?” Financial assistance was measured by the question “How often do the people in your place of worship help you financially?” Response formats for both of these questions used a 4-point Likert scale with a response range of never =1 to very often = 4. Emotional support received from congregational members was assessed with 3 items which comprised an index of emotional support. These items were: How often do the people in your place of worship make you feel loved and cared for? How often do they listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns? and How often do they express interest and concern in your wellbeing? Each question used the same response format [Very often (4), fairly often (3), not too often (2), or never (1)?]. Values for the 3 questions were summed resulting in a range of index scores from 3 to 12; higher values represent more frequent emotional support received from congregational members. Cronbach’s alpha for the three-item index indicating receipt of emotional support is .72 for African American and .72 for Black Caribbean adolescents.

Providing support.

Adolescents were asked how often they provided help to congregational members in the form of overall assistance, help with chores, and help during an illness. Providing overall assistance was measured by the question “How often do you help out people in your place of worship?” The question for chores was worded: How often do you help the people in your place of worship with regular chores such as shopping, cleaning or yard work? The question for providing help during an illness was worded: How often do you help when they are sick or ill?” Response formats for these questions used a 4-point Likert scale with a response range of never =1 to very often = 4 [Would you say very often (4), fairly often (3), not too often (2), or never (1)?]. Higher values indicated providing support to congregational members more frequently.

Independent Variables

Our analysis examined several sociodemographic correlates (i.e., ethnicity, age, gender, family income level and region) of church support. Ethnicity is represented as a dichotomous variable (African American or Black Caribbean), age is coded in years, gender is a dichotomous variable and family income is continuous and coded in dollars. The categories of region are tailored to the respective demographic distribution of the African American and Black Caribbean populations in the U.S. There are four categories of region for African Americans (Northeast, North Central, South, West) and two categories for Black Caribbeans (Northeast, Other). These region categories reflect the geographic distribution of these two populations, with Black Caribbeans being highly concentrated in the Northeast (e.g., New York, Connecticut, Washington, D.C.) and only a few in the North Central and West regions. The analyses for Black Caribbeans includes a Caribbean-specific variable for country of origin. Black Caribbean respondents reported over 25 different countries of origin. This variable, country of origin, was recoded into four categories: Jamaica, Haiti, Trinidad & Tobago, and other English-speaking country (e.g., Barbados).

Our analysis also includes two measures of integration with congregations: frequency of service attendance and frequency of participating in congregational activities. Frequency of religious service attendance is measured by the question: “How often do you usually attend religious services? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or less than once a year?” (Nearly Everyday = 4), (at least once a week=3) (a few times a month=2), (a few times a year =1). Frequency of participating in congregational activities is measured by the question “Besides regular services, how often do you take part in other activities at your place of worship? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or never? (Nearly Everyday = 5), (at least once a week=4) (a few times a month=3), (a few times a year =2), (never = 1).

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1.3, which uses the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex design-based estimates of variance. The percentages represent weighted proportions to approximate the national population distributions of African American and Black Caribbean adolescents. Linear regression analyses investigated the impact of demographic and congregational integration factors on the receipt and provision of church support. Two regression models are presented for each dependent variable. The first regression model (Model 1) includes all of the independent variables and frequency of service attendance. The second regression model (Model 1a) includes all of those previously in Model 1 with the addition of frequency of congregational activities. All analyses utilize sampling weights to adjust for non-independence in selection probabilities within households, as well as non-response rates across households and individuals. Analyses also take into account the complex design of the NSAL-A sample to produce nationally representative population estimates and standard errors that are generalizable to the African American and Black Caribbean adolescent populations.

Results

Roughly 7 out of 10 African American and 6 out of 10 Black Caribbean adolescents report that they receive overall support from church members on a very or fairly often basis. Forty percent of African American and 30% of Black Caribbean youth indicate receiving financial assistance very/fairly often, while both groups indicate comparable mean values for receiving emotional support (M = 8.99 and 8.88). A little over half of both groups indicated that they provided overall assistance to others on a very/fairly often basis. African American youth were more likely than Black Caribbean youth to indicate that they provide help with chores and help during illness on a very/fairly often basis. The regression analysis of ethnic differences in receipt and provision of church support is presented in Table 2. Results indicate no significant ethnicity differences between African American and Black Caribbean adolescents for receiving church-based support (i.e., overall assistance, financial and emotional support) or providing (overall assistance, chores, and help during illness).

Table 2.

Regression Analysis of Ethnic Differences between African American Adolescents and Black Caribbean Adolescents on the Receipt and Provision of Church Based Social Support

| Independent Variables | Frequency of Receiving Overall Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Financial Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Emotional Support | Frequency of Providing Overall Assistance | Frequency of Providing Chores | Frequency of Providing Help during an Illness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| African American | 0.08(0.20) | 0.06(0.16) | 0.15(0.23) | 0.14(0.19) | −0.29(0.20) | −0.38(0.22) | 0.09(0.15) | 0.06(0.12) | 0.10(0.16) | 0.08(0.13) | −0.07(0.09) | −0.10(0.12) |

| Black Caribbean | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R-Square | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| F | 10.29*** | 13.37*** | 5.69*** | 20.88*** | 7.63*** | 24.25*** | 7.74*** | 18.19*** | 6.07*** | 12.62*** | 10.09*** | 30.01*** |

| df | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| N | 965 | 965 | 873 | 873 | 1031 | 1031 | 984 | 984 | 922 | 922 | 922 | 922 |

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

b=unstandardized coefficient; SE=standard error

Regressions control for: Gender, age, income, region, frequency or religious service attendance and participation in congregational activities.

Ethnicity: African Americans=1, Black Caribbeans=0

Table 3 presents the regression analysis for frequency of receiving support from congregational members. Age and region were significantly associated with overall assistance (Table 3). Older adolescents reported receiving less overall assistance. African American adolescents who resided in the South reported receiving overall assistance less frequently than residents of the North Central region, but more frequently than those who live in the West. African American adolescents who had higher family incomes received financial assistance from congregation members than their lower income counterparts. African American adolescents who resided in the North Central region received emotional support more frequently than Southerners. Lastly, both frequency of service attendance and frequency of congregational activities were positively associated with all three receipt of support variables. However, although frequency of service attendance was significant in Model 1, the addition of frequency of congregational activities in Model 1a rendered the relationship insignificant (for all three variables).

Table 3.

Regression Analysis of the Religion and Demographic Variables on the Receipt of Support from Church Members among African American Adolescents

| Independent Variables | Frequency of Receiving Overall Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Financial Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Emotional Support | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Age | −0.08(0.03)* | −0.06(0.03)* | −0.04(0.03) | −0.02(0.03) | 0.01(0.06) | 0.03(0.06) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.07(0.09) | −0.09(0.09) | 0.13(0.10) | −0.16(0.10) | −0.06(0.20) | −0.02(0.18) |

| Household Income | −0.00(0.00) | 0.00(0.00) | −0.01(0.01)* | −0.01(0.01)* | −0.00(0.01) | 0.00(0.01) |

| Region | ||||||

| North Central | 0.26(0.11)* | 0.25(0.12)* | −0.02(0.15) | −0.02(0.14) | 0.76(0.19)**** | 0.72(0.16)**** |

| Northeast | 0.16(0.15) | 0.15(0.13) | −0.01(0.19) | −0.01(0.19) | −0.31(0.33) | −0.37(0.38) |

| West | −0.21(0.11) | −0.27(0.12)* | −0.27(0.19) | −0.35(0.19) | −0.22(0.47) | −0.40(0.41) |

| South | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Frequency of Service Attendance | 0.27(0.04)*** | 0.09(0.05) | 0.21(0.06)** | 0.00(0.06) | 0.61(0.13)*** | 0.10(0.14) |

| Participation in Congregational Activities | ---- | 0.28(0.04)*** | ----- | 0.31(0.04)*** | ------- | 0.72(0.10)*** |

| R-Square | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| F | 10.48*** | 14.32*** | 5.66*** | 21.38*** | 6.12*** | 23.29*** |

| Df | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| N | 680 | 680 | 633 | 633 | 721 | 721 |

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

b=unstandardized coefficient; SE=standard error

Several independent variables are represented by dummy variables. Gender: 0=male, 1=female; Region: South is the comparison category.

The regression analysis for the provision of support to congregational members among African American adolescents is presented in Table 4. No sociodemographic variables were significantly associated with the provision of support in the full models (Model 1a); a previously significant negative association between household income and providing help during an illness was insignificant in the full model. Similar to receiving support, both frequency of service attendance and frequency of congregational activities were positively associated with all three provision of support variables. In each Model 1, frequency of service attendance was significant, but including frequency of congregational activities rendered service attendance insignificant.

Table 4.

Regression Analysis of the Religion and Demographic Variables on the Provision of Support to Church Members among African American Adolescents

| Independent Variables | Frequency of Providing Overall Assistance | Frequency of Providing Chores | Frequency of Providing Help during an Illness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Age | −0.04(0.03) | −0.02(0.02) | −0.04(0.03) | −0.03(0.03) | −0.04(0.03) | −0.04(0.03) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.01(0.08) | −0.03(0.08) | 0.13(0.08) | −0.15(0.09) | 0.04(0.09) | −0.07(0.09) |

| Household Income | 0.00(0.00) | 0.00(0.00) | −0.00(0.00) | −0.00(0.00) | −0.01(0.00)* | −0.01(0.00) |

| Region | ||||||

| North Central | 0.10(0.11) | 0.10(0.08) | 0.03(0.13) | 0.03(0.10) | 0.06(0.15) | 0.05(0.14) |

| Northeast | 0.02(0.12) | 0.01(0.11) | −0.02(0.20) | −0.03(0.20) | −0.00(0.13) | −0.02(0.12) |

| West | 0.04(0.21) | −0.02(0.23) | −0.08(0.20) | −0.15(0.20) | −0.06(0.14) | −0.12(0.14) |

| South | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Frequency of Service Attendance | 0.29(0.05)*** | 0.10(0.05) | 0.30(0.07)*** | 0.10(0.08) | 0.29(0.05)*** | 0.11(0.07) |

| Participation in Congregational Activities | ----- | 0.28(0.04)*** | ----- | 0.29(0.04)*** | ----- | 0.26(0.05)*** |

| R-Square | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| F | 7.16*** | 17.54*** | 7.20*** | 14.2*** | 11.01*** | 30.32*** |

| df | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| N | 688 | 688 | 661 | 661 | 664 | 664 |

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

b=unstandardized coefficient; SE=standard error

Several independent variables are represented by dummy variables. Gender: 0=male, 1=female; Region: South is the comparison category.

Table 5 presents the regression analysis for receiving church support for Black Caribbean adolescents. Household income, region, service attendance and congregational activities were significantly related to frequency of receiving overall assistance. Household income was positively associated with frequency of receiving overall assistance, and Black Caribbean adolescents in the Northeast were less likely to receive overall support compared to those residing in other regions. Both frequency of service attendance and frequency of congregational activities were positively associated with receiving overall support.

Table 5.

Regression Analysis of the Religion and Demographic Variables on the Receipt of Support from Church Members among Black Caribbean Adolescents

| Independent Variables | Frequency of Receiving Overall Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Financial Assistance | Frequency of Receiving Emotional Support | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Age | −0.10(0.05) | −0.07(0.05) | 0.00(0.05) | 0.05(0.06) | −0.28(0.07)** | −0.20(0.09)* |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.00(0.24) | −0.04(0.23) | 0.17(0.17) | −0.21(0.19) | −0.42(0.37) | 0.39(0.33) |

| Household Income | 0.04(0.02)* | 0.04(0.01)* | −0.04(0.01)* | −0.04(0.01)* | −0.02(0.06) | −0.02(0.06) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | −0.72(0.17)*** | −0.61(0.15)** | −0.28(0.41) | −0.25(0.34) | −0.92(0.45) | −0.71(0.38) |

| Country of Origin | ||||||

| Jamaica | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Haiti | −0.25(0.15) | −0.13(0.15) | −0.10(0.23) | −0.02(0.21) | −0.44(0.44) | −0.20(0.45) |

| Trinidad-Tobago | −0.14(0.31) | −0.09(0.32) | −0.19(0.34) | −0.11(0.36) | 0.45(0.41) | 0.61(0.42) |

| Other | 0.32(0.22) | 0.41(0.19) | 0.28(0.20) | 0.34(0.19) | 0.66(0.31) | 0.94(0.44)* |

| Frequency of Service Attendance | 0.33(0.07)*** | 0.22(0.07)** | 0.27(0.08)** | 0.16(0.09) | 0.48(0.15)** | 0.23(0.22) |

| Participation in Congregational Activities | ---- | 0.21(0.07)** | ----- | 0.18(0.06)** | ----- | 0.44(0.22)# |

| R-Square | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| F | 29.74*** | 159.51*** | 5.08** | 13.35*** | 12.90*** | 27.73*** |

| df | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| N | 282 | 282 | 237 | 237 | 306 | 306 |

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

p<.07

b=unstandardized coefficient; SE=standard error

Several independent variables are represented by dummy variables. Gender: 0=male, 1=female; Region: 0=Other, 1=Northeast; Country of Origin: Jamaica is the comparison category.

In terms of receiving financial assistance, household income was negatively associated with this form of support (Table 5). Both service attendance and congregational activities were positively associated with receiving financial assistance, but service attendance was not significant in the full model (Model 1a). In terms of emotional support, age was negatively associated, such that older adolescents reported less frequent emotional support than their younger counterparts. Service attendance was significantly associated with receiving emotional support in the reduced model (Model 1), but not the full model (Model 1a) and congregational activities only bordered significance (p<.07).

The regression analysis for frequency of providing church support (Table 6) indicates that age was significant for all three dependent variables; older adolescents provided support less frequently to congregation members than their younger counterparts. Boys were less likely to provide help during an illness than adolescent girls. Household income was positively associated with frequency of providing overall assistance and providing help during an illness. Black Caribbean adolescents living in the Northeast provided help during illness less frequently than those residing in all ‘Other’ regions. The sole country of origin finding indicates that Black Caribbean adolescents who indicated ‘Other’ provide overall assistance and help during illnesses more frequently than the comparison group (Jamaica). Service attendance was positively associated with providing overall assistance but was unrelated with the addition of congregation activities (Model 1a). Frequency of participation in congregational activities was positively related to providing overall assistance and providing help with chores, but not for help during an illness.

Table 6.

Regression Analysis of the Religion and Demographic Variables on the Provision of Support to Church Members among Black Caribbean Adolescents

| Independent Variables | Frequency of Providing Overall Assistance | Frequency of Providing Chores | Frequency of Providing Help during an Illness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | Model 1 | Model 1a | |

| b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |

| Age | −0.15(0.04)** | −0.10(0.02)*** | −0.18(0.04)*** | −0.14(0.05)* | −0.18(0.06)* | −0.14(0.05)* |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.01(0.07) | −0.04(0.09) | −0.16(0.08) | 0.15(0.10) | −0.28(0.06)*** | 0.27(0.07)** |

| Household Income | 0.03(0.01)* | 0.03(0.01)* | −0.01(0.02) | −0.01(0.02) | 0.06(0.02)** | 0.06(0.02)** |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | −0.49(0.43) | −0.34(0.31) | 0.12(0.30) | 0.22(0.20) | −0.58(0.27) | −0.49(0.18)* |

| Country of Origin | ||||||

| Jamaica | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Haiti | 0.03(0.21) | 0.18(0.14) | 0.05(0.22) | 0.17(0.25) | −0.05(0.16) | 0.06(0.14) |

| Trinidad-Tobago | −0.20(0.23) | −0.10(0.25) | −0.05(0.37) | 0.10(0.37) | 0.04(0.14) | 0.17(0.12) |

| Other | 0.33(0.14)* | 0.49(0.12)** | 0.46(0.44) | 0.59(0.43) | 0.58(0.11)*** | 0.69(0.10)*** |

| Frequency of Service Attendance | 0.27(0.08)** | 0.12(0.14) | 0.06(0.08) | −0.07(0.11) | 0.13(0.12) | 0.01(0.18) |

| Participation in Congregational Activities | ----- | 0.27(0.07)** | ----- | 0.21(0.05)** | ----- | 0.19(0.10) |

| R-Square | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.24 |

| F | 27.62*** | 187.23*** | 104.47*** | 62.73 | 22.31*** | 69.35*** |

| df | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| N | 293 | 293 | 257 | 257 | 254 | 254 |

p<.05

p< .01

p<.001

b=unstandardized coefficient; SE=standard error

Several independent variables are represented by dummy variables. Gender: 0=male, 1=female; Region: 0=Other,

1=Northeast; Country of Origin: Jamaica is the comparison category.

Discussion

This study investigated church support networks of African American and Black Caribbean adolescents. There is extremely limited research on religious participation among adolescents and even less research on church support networks regardless of race and ethnicity. Overall, we found that many Black adolescents report significant involvement with church networks and members as both the recipients and providers of various forms of assistance. Notably, 2 out of 3 Black adolescents report receiving overall assistance very or fairly often and more than half report providing overall assistance very or fairly often. An examination of the 3 emotional support indicators revealed that a greater percentage of adolescents reported that congregational members made them feel loved, followed by expressed interest in their well-being and then listen to you talk about your problems and concerns (data not shown). There were no significant differences between African American and Black Caribbean adolescents’ involvement in church support networks with both groups receiving support from and providing support to church networks at largely comparable levels. A brief review of multivariate findings indicates both expected and unanticipated findings.

One of the main limitations of research on the impact of religiosity is the over reliance of the frequency of service attendance as the sole indicator of religious involvement and as well as integration in congregations. Our analysis of African American adolescents shows that for each dependent variable service attendance is significantly related to all six dependent variables. The introduction of controls for congregational activities, however, eliminated the previously significant effects for service attendance. This overall pattern is similar but not as consistent for Black Caribbeans. Substantively, this indicates that while both variables are associated with greater involvement in support exchanges, African American and Black Caribbean adolescents’ actual involvement in congregation activities are more consequential for garnering and giving support than merely attending religious services. Parents and other family members may compel adolescents’ attendance at religious services so that being obligated to attend does not fully represent engagement with the people and activities in faith settings. For both adolescents and adults, some individuals fully engage with their congregations whereas others may attend religious services frequently, but not interact with fellow congregation members. It is important to note that religious service attendance has long been recognized as one of the most robust and positive correlates of health and social well-being outcomes (Koenig et al., 2012). However, these and other findings suggest that service attendance essentially functions as a proxy for other church activities and connections that are more directly relevant for outcomes (see Chatters et al., 2018). Our findings that participation in congregational activities and service attendance are consistent with other research on both African Americans (Taylor, Lincoln & Chatters, 2005) and Black Caribbean adults (Nguyen et al., 2016) that integration in church networks is positively associated with receiving and giving support on a more frequent basis. This is one of the most consistent findings in the church support, as well as the family support literatures (Chatters et al., 2002).

There were several demographic differences in church support networks with significant age differences among both Black Caribbeans and African Americans. Age was related was related to the provision of support among Black Caribbean adolescents such that older adolescents were less likely than their younger cohorts to provide support (overall, chores and help during illness) to others. This may be due to maturational and social changes evident among late adolescents. Presumably, this group has stronger links and associations with peer groups and outside activities (school) that compete for their discretionary time. Older Black Caribbean adolescents also received emotional support less frequently than their younger counterparts. Late adolescents are more cognitively sophisticated, aware, and independent which may result in weaker ties to church networks and communities as sources of emotional support. On the other hand, for African American adolescents, younger age was associated with receiving more overall assistance from church members which is in keeping with expectations for age differences in receiving assistance.

Surprisingly, gender differences in receiving and giving support were especially meager. This runs counter to general expectations that girls’ socialization to gender roles prepares them to be involved in support relationships, particularly in providing support to others (Flaherty & Richman, 1989). Interestingly, the only gender difference involved Black Caribbean girls who provided help during illness more frequently than did boys. It is noteworthy that this particular type of assistance, providing care during illness, is especially gendered and consistent with expectations that girls and women are involved in caregiving (Shumaker & Hill, 1991). Household income differences indicated that African American youth from higher income families were less likely to receive financial assistance and less likely to provide support during illness (marginal finding). Among Black Caribbean youth, higher household income was associated with receiving overall assistance, providing overall assistance, and providing help during illness on a more frequent basis. However, higher household income was associated with receiving financial assistance less frequently, presumably indicating that family monetary resources were sufficient. Contradicting findings for regional differences in religious involvement in adult samples, African American youth residing in the North Central received overall assistance and emotional support more frequently than did Southern youth. Future research on regional differences in religious participation among African American adolescents is needed to help understand these findings.

The collection of findings taken together demonstrates that Black Caribbean and African American adolescents are similar with respect to receiving and providing various forms of social support within their church-based networks. Findings from separate sets of multiple regression analyses were conducted to better understand the separate and unique correlates that characterize support relationships for these groups. Sociodemographic factors were largely meager overall in terms of explaining receiving and providing support. One notable exception is the impact of older age in curtailing frequency of support provision to others among Black Caribbean youth. Significant findings for service attendance and, particularly, involvement in non-service church activities, underscores the importance of involvement and engagement in the life of the church for both receiving and providing support. Consistent with other work, participation in church activities (e.g., service attendance, church groups) is associated with greater likelihood of receiving and providing assistance to church members (Nguyen et al., 2016).

Limitations & Next Steps

Limitations of the present study should be addressed. This study’s specific focus was to explore how sociodemographic and church involvement correlates were associated with receiving and providing church-based support among Black Caribbean and African American adolescents. Study strengths included the sample’s large numbers of Black youth representing both ethnic and social status diversity, the availability of survey items that tapped different forms of social support (general, financial, emotional, chores and illness care), and the use of multivariate procedures to assess the independent effects of sociodemographic and church involvement factors on support relationships. This study addressed the absence of Black adolescent involvement in church-based support networks in the literature; however, it represents only a beginning effort in understanding very complex and nuanced interactions and relationships.

Specific data on the sources of support or the duration of supportive relationships was not available. The church support given by a religious leader or figure (e.g., priest, pastor, imam, deacon) may function differently than that provided by a fellow peer or a lay church leader or member. Additional work is needed to ascertain whether these and other differences in support relationships are evident within specific ethnicity and congregational groups. Information is needed as to what types of support-yielding relationships may be more important for Black youth across ethnicity and in relation to their age, gender, and maturational level. For example, some Black Churches offer opportunities for formal mentoring, where ordained and lay congregational leaders serve as role models for congregational youth.

The cross-sectional design of the study allowed a broad assessment of Black youth’s involvement in church-based support networks. Black Caribbean and African American youth were similar with respect to involvement in church-based support. However, observed differences in the sociodemographic correlates of receiving and giving aid may be linked to broader issues associated with the history and purpose of their respective religious communities. For example, Black Caribbean churches may embody an identity and purpose as an ‘immigrant church’ with a focus on serving individuals and families experiencing geographic relocations, social transitions, and resettlement (Chaze, Thomson, George, & Guruge, 2015; Emerson, Korver-Glenn, & Douds, 2015; Shapiro, 2018). These churches also heavily incorporate the language and culture of the country of origin. Continuing work on Black youth involvement in church-based support networks will need to consider how support types and relationships are best matched with adolescents of different ethnicities and ages (young, middle and late adolescence) and who are experiencing ongoing developmental and maturational changes. Identifying the characteristics that contribute to a close goodness-of-fit between adolescents and their religious community may be a significant step toward understanding the ways in which religious contexts sustain support. Future research should also explore how different sources of support intersect. For example, some individuals may have strong congregation and extended family based support networks. Additionally, some adolescents may be heavily involved in church networks and youth-based congregational programs so that the majority of their friends and peers are also their congregation members. This initial investigation of the correlates of church-based social support networks for Black youth highlights the long-standing importance of church as a supportive institution for both African Americans and Black Caribbeans across the life span.

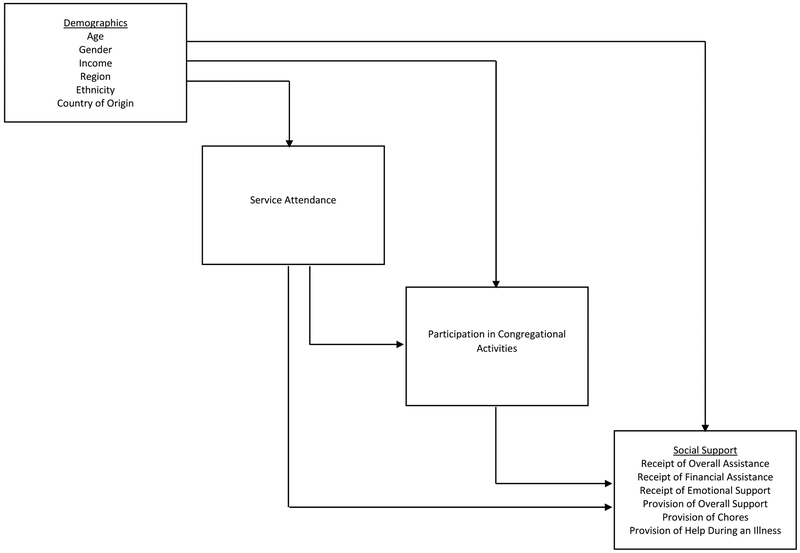

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the receipt and provision of church support for Black adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest:The data collection for this study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716), with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging to RJT (P30AG1528) and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences to LMC (R25GM05864).

Footnotes

Ethical Approval:

Data collection for the NSAL Adolescent Supplement was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent:

Prior to conducting the interview, informed consent was obtained from the adolescent’s legal guardian and assent was obtained from the adolescent.

Contributor Information

M.O. Hope, Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture and Health, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

R.J. Taylor, School of Social Work and Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109,

A.W. Nguyen, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106,

L.M. Chatters, School of Social Work, School of Public Health and Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

References

- Ball J, Armistead L, & Austin BJ (2003). The relationship between religiosity and adjustment among African-American, female, urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 26(4), 431–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SL (2015). To educate, equip, and empower: Black church sponsorship of tutoring or literary programs. Review of Religious Research, 57(1), 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, & Glass T (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social Epidemiology, 1, 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Butler-Barnes ST, Martin PP, Copeland-Linder N, Seaton EK, Matusko N, Caldwell CH, & Jackson JS (2018). The protective role of religious involvement in African American and Caribbean Black adolescents’ experiences of racial discrimination. Youth & Society, 50(5), 659–687. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, & Hope MO (2018). Church and family support networks and depressive symptoms among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 403–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ& Lincoln KD (1999). African American religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,38(1), 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, & Schroepfer T (2002). Patterns of informal support from family and church members among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies, 33(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chaze F, Thomson MS, George U, & Guruge S (2015). Role of cultural beliefs, religion, and spirituality in mental health and/or service utilization among immigrants in Canada: a scoping review. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 34(3), 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Lewis YC, Gipson PY, Opperman KJ, Arango A, & King CA (2016). Protective role of religious involvement against depression and suicidal ideation among youth with interpersonal problems. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4), 1172–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue MJ, & Benson PL (1995). Religion and the well‐being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues, 51(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Levin JS (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 25(6), 700–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson MO, Korver-Glenn E, & Douds KW (2015). Studying race and religion: A critical assessment. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(3), 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty J, & Richman J (1989). Gender differences in the perception and utilization of social support: Theoretical perspectives and an empirical test. Social Science & Medicine, 28(12), 1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooden AS, & McMahon SD (2016). Thriving among African‐American adolescents: Religiosity, religious support, and communalism. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(1–2), 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby BJ, Caldwell CH, Bellatorre A, & Jackson JS (2012). Ethnic differences in family stress processes among African-Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of African American Studies, 16(3), 406–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MO, Assari S, Cole-Lewis YC, & Caldwell CH (2017). Religious social support, discrimination, and psychiatric disorders among Black adolescents. Race & Social Problems, 9(2), 102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, … & Williams DR (2004). The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BR, Jang SJ, De Li S, & Larson D (2000). The ‘invisible institution’and Black youth crime: The church as an agency of local social control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(4), 479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King D, & Carson VB (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2006). Church-based social support and mortality. The Journals of Gerontology [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(3), S140–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause NM (2008). Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters LM, & Taylor RJ (2005). Religion, health, and medicine in African Americans: Implications for physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97, 237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, & Mamiya LH (1990). The black church in the African American experience. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR (2007). Who are the other African Americans? Contemporary African and Caribbean immigrants in the U.S In Shaw-Taylor Y & Tuch S (Eds.), Other African Americans: Contemporary African and Caribbean families in the United States (pp. 49–68). Boulder, CO: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Teti DM, Corns KM, Vieira-Baker CC, Lavine JR, Gouze KR, & Keating DP (1996). Cultural specificity of support sources, correlates and contexts: Three studies of African-American and Caucasian youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 551–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree DH, Wingood GM, DiClemente R, Davies S, & Harrington KF (2003). Religiosity and risky sexual behavior in African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(1), 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2016). Church-based social support among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research, 58(3), 385–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RH, Billingsley A, Caldwell CH (1994). The role of the black church in working with black adolescents. Adolescence. Summer; 29(114):251–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, & Tyson K (2018). The Intersection of Race and Gender Among Black American Adolescents. Child Development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, & Hill DR (1991). Gender differences in social support and physical health. Health Psychology, 10(2), 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E (2018). Places of habits and hearts: Church attendance and Latino immigrant health behaviors in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C (2003). Theorizing religious effects among American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Denton ML, Faris R, & Regnerus M (2002). Mapping American adolescent religious participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(4), 597–612. [Google Scholar]

- Steinman KJ, & Zimmerman MA (2004). Religious activity and risk behavior among African American adolescents: Concurrent and developmental effects. American Journal of Community psychology, 33(3–4), 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (1988). Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM & Levin J (2004). Religion in the Lives of African Americans:Social, Psychological and Health Perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Lincoln KD, & Woodward AT (2017). Church-based exchanges of informal social support among African Americans. Race and Social Problems, 9(1), 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Woodward AT, & Brown E (2013). Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin and congregational informal support networks. Family Relations, 62, 609–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, & Chatters LM (2005). Supportive relationships with church members among African Americans. Family Relations, 54(4), 501–511. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Mouzon DM, Nguyen AW, & Chatters LM (2016). Reciprocal family, friendship and church support networks of African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life, Race and Social Problems, 8(4), 326–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC (1999). Black Identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]