Abstract

Individuals with serious mental disorder diagnoses (SMD) are overrepresented in U.S. jails and prisons, returning to custody more often and more quickly than those without these diagnoses. This paper examines the strengths and limitations of existing theoretical interpretations of justice involvement among those with SMD and presents results from in-depth interviews (n = 23) in an effort to direct an alternative theoretical path. Findings indicate people with SMD are not simply subject to the whims of their psychopathology, and instead are risk-exposed agents whose arrests are related to early institutionalization, interpersonal conflict, and life circumstances punctuated by socioeconomic marginality. Such findings suggest longitudinal and multi-level theoretical orientations are most appropriate for understanding carceral involvement among individuals with SMD.

Keywords: criminal behaviour, mental illness, substance use, criminalization

Introduction

In the United States, carcerally-involved individuals with serious mental disorder diagnoses (SMD) represent criminal subjects around which much uncertainty and controversy circulates.i In the absence of a nationally representative or methodologically sound assessment of prevalence, best estimates indicate one out of every seven men and one out of every three women in U.S. jails has a SMD (Fazel and Danesh 2002; Steadman et al. 2009). Such rates are approximately three times greater than those found in the general population (Kessler et al. 2001; Teplin 1990). Despite widespread belief that the prevalence of mental disorder diagnoses in jails and prisons increased in the latter 20th century, there is no longitudinal data that indicates these rates have risen disproportionate to the overall increase in incarceration (Hiday and Burns 2010). However, spending longer periods of time incarcerated (Ditton 1999) and being re-arrested more often and more quickly than their relatively well counterparts (Baillargeon et al. 2010; Cloyes et al. 2010), these individuals comprise one sub-group challenging U.S. decarceration efforts.

Two divergent theoretical orientations explain how individuals with SMD come to be overrepresented in jails and prisons, and provide direction for intervention. The first orientation, proposed by practitioner advocates, relies on theories of deinstitutionalization and criminalization and identifies enhancement of mental health treatment participation as a solution. The second orientation, proposed largely by academic experts, relies on theories of criminogenic risk and identifies risk identification and reduction as a solution. To date, the social construction of these two dominant conceptualizations remains unexamined, leaving questions regarding their implications and gaps. Furthermore, despite recognition of the important contribution of the subjectivities of those who are carcerally involved to understanding criminal risk (Sexton 2015), existing theoretical orientations fail to integrate first-hand experiences of individuals with SMD.

Decreasing justice involvement for individuals with SMD necessitates clarity regarding their pathways to incarceration. Scholars have previously explored the empirical literature on this phenomenon, raising criticism with criminalization orientations (e.g., Fisher et al. 2006; Prins 2011). Research that extends beyond criminalization is limited. Some studies suggest carceral involvement for those with SMD is related to substance misuse (Bonta et al., 2008), deleterious relationships (Silver 2002; Skeem et al. 2009), victimization (Silver and Teasdale 2005), and neighborhood disadvantage (Silver 2000), but the way in which these and other social and structural factors unduly burden and interact with individual characteristics to enhance risk of arrest is unclear (Draine et al. 2002; Fisher et al. 2006). Generally, the life circumstances of carcerally-involved individuals with SMD are opaque.

This paper first examines existing interpretations of the representation of individuals with SMD in carceral systems, describing how they relate to broader conceptualizations of mental illness and criminal risk, and discussing the way in which they bias interpretations of the problem and obscure alternative theories. Next, the paper presents theoretically informative research that takes one step toward a situated understanding of this phenomenon. Inductively building from the experiences of carcerally-involved individuals with SMD, the study asks: how do individuals with SMD describe the proximal and distal events and circumstances precipitating arrest? And, how do they relate these experiences to their carceral involvement? Our findings indicate entrenchment relates to previous institutionalization, mental states of deliberation and intoxication, social conflict, and socioeconomic marginality, and that risk for arrest is best understood as accumulative, interactive, social, and across individual and structural levels. These results indicate the need to draw on alternative theories, such as life course and risk environment, to fully understand how individuals with SMD come to be represented in carceral systems.

Conceptualizations of carceral representation for individuals with SMD

Social problems come to be valued and defined not from some essential meaning or significance, but through collective processes of definition and prioritization (Blumer 1971). Similarly, shifts in criminology reflect more than their practical or empirical validity; they also reflect the scientific, demographic, political, and economic specificities of their time (Allen 1981; Foucault 1975; Hannah-Moffat 1999; Rusche and Kirchheimer 1939; Simon 2013). The social construction of criminality among individuals with SMD, acts as a case through which changes in explanatory theories illustrate such specificities. Below, we describe dominant theoretical orientations to explaining the overrepresentation of people with SMD in carceral systems, examining their influences and biases. We also introduce potential alternative theoretical orientations for understanding this phenomenon.

Criminalized patients

Explanatory models employing “deinstitutionalization” and “criminalization” frameworks have long dominated conversations regarding the representation of individuals with SMD in jails and prisons (e.g., Abramson 1972; Lamb 2015). Proponents argue that the closing of state mental hospitals beginning in the mid-1950s-- and ultimately leading to the release of 90% of those institutionalized (Segal and Jacobs 2014)-- resulted in a significant number of individuals with SMD entering communities without adequate mental health services or housing. Subsequently, in the absence of resources, symptoms increased and impairment led to criminal behavior, non-normative and disruptive behavior became “criminalized,” and/or arrest became a “compassionate” means of meeting basic needs (Abramson 1972; Mechanic 2007).

The criminalization orientation emerged as deinstitutionalization increased. In 1972, speaking from his observations of rising arrest rates among former patients, psychiatrist Marc Abramson coined the now popular term “criminalization of mental illness.” Abramson represented a body of professionals recently disempowered by increasingly restrictive psychiatric commitment laws, which diminished their capacity to force hospitalization (e.g. the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act). Subsequently, advocacy groups comprised of practitioners and kin to those with SMD (e.g. National Alliance of the Mentally Ill [NAMI], Treatment Advocacy Center [TAC],) argued that biologically-based symptoms drive illegal behavior and, thus, strengthening psychiatric commitment laws and increasing funding for psychiatric services are necessary to prevent justice-involvement.

This conceptualization largely represents the criminal subject as a criminalized patient and reflects the perspectives of practitioner advocates, over the subjects themselves or empirical evidence. The criminalized patient orientation biases interpretations of the overrepresentation of individuals with SMD by portraying members of this population as one dimensional, reducing the criminalized patient to a victim of their inherent and biologically based symptoms and, in some cases, the discrimination they face as a result of their disease. Criminalized patients are people “with untreated brain disorders” who either commit crimes directly because of their illnesses or because their illness impairs their ability to acquire protective resources (e.g., housing; TAC, n.p.). In turn, this orientation criticizes penal responses to the mental health and socioeconomic needs of this population, while promoting treatment as the primary solution to reducing incarceration.

Several review articles have raised valid critiques of the evidentiary basis of the criminalized patient perspective (see Draine et al. 2002; Mulvey and Schubert 2017; Skeem et al. 2011). In recent years, empirical research has undermined several elements of the criminalized patient argument. To start, access to psychiatric services and symptoms are weakly, if at all, linked to arrests. At a macro level, neither psychiatric hospital closures nor spending on psychiatric services regularly predict arrest rates, while much of the role of psychiatric hospital bed availability appears moderated by a city’s rate of homelessness (Erickson et al. 2008; Markowitz 2006). At an individual level, several studies now suggest that symptoms are directly and clearly involved in only about 8 to 15 percent of arrests among individuals with SMD (Junginger et al. 2006; Peterson et al. 2010; 2014).

Despite the weak links between services, symptoms, and arrests, the criminalized patient perspective remains popular. The perspective is at least in part bolstered by the inverse correlation between psychiatric hospitalization rates and imprisonment rates in the U.S. Empirical research finds the relation between deinstitutionalization rates and incarceration rates is largely spurious (see Raphael and Stoll 2013). Yet, the intuitive appeal of inferring a causal relationship between decreasing rates of psychiatric institutionalization and overall increasing rates of incarceration has proven a powerful rhetorical tool for justifying increased investment in psychiatric services. As U.S. criminal justice policy makers seek decarceration possibilities, practitioner-advocates are chiming in, maintaining their focus on the criminalized patient subject and asking to “bring back the asylum” to reduce incarceration (Sisti et al. 2015).

High risk/need offenders

The last decade has brought a shift in the conceptualization of criminal subjects in general, transitioning from “predators” in need of containment toward “transformative risk subjects” with respective “risk/needs” and hope of rehabilitation (Hannah-Moffat 2005; Russell and Carlton 2013; Simon 2014). Meanwhile, policy makers have shifted the focus of incarceration from incapacitation to individual deterrence, viewing recidivism reduction fundamental to decreasing incarceration rates. Academic experts, largely from criminology and psychology, argue that such reduction must be informed by research that identifies modifiable recidivism risk factors in populations at greatest risk of re-arrest (Andrews and Bonta 2010). With this shift in focus, individuals with SMD are viewed less as criminalized patients and more as high risk/need offenders; individuals with SMD are a sub-population of the carcerally-involved, high in risk/need and requiring intervention.

The risk/need approach has utilitarian appeal; risk factors for re-arrest are assessed and intervention directed. Causal risk factors, defined as those that a) can be altered by intervention and that b) when altered change the probability of recidivism (Monahan and Skeem 2014), can be tested via experimental and quasi-experimental research designs. These studies provide important clarification regarding some risk factors. For example, contrary to the criminalized patient approach, the high risk/need offender approach highlights the failure of community supervision models to impact recidivism via symptom reduction, drawing into question the essential role of symptoms in causing criminality and indicating the need for interventions that address more than symptoms (Skeem et al. 2011). Instead of inherent symptoms, this orientation promotes expanding focus to also include risk factors that are dynamic and general (i.e., changeable and shared with other offenders; Peterson et al. 2010).

Research from the risk/need orientation has, in some ways, promoted more rigorous research on risk factors for carceral involvement among those with SMD. Though, on its own, the risk/need orientation presents a constrained view of carceral involvement. First, by focusing on recidivism, attention is diverted from factors that initially lead to carceral involvement. In other words, the question of focus becomes “what risk factors can be altered today to reduce recidivism tomorrow?” instead of, “what factors initially, directly or indirectly, led to carceral involvement and how can we prevent involvement for others?” Answering the first question has important implications for the carcerally-involved and their recidivism reduction. It does not provide insight for primary prevention, and neglects the fact that the number of incarcerated individuals with SMD today exceeds the number of all inmates in 1972. Relatedly, contemporary risk/need approaches focus on modifiable risk factors (Hannah-Moffat 2005). Modifiable risk factors are, to some degree, limited to those perceived as practically intervenable. As a result, identification of sociopolitical conditions that enhance risky behavior (e.g., social exclusion facilitating substance use) or policies that define deviant behavior as illegal (e.g., penal responses to substance use) are less relevant.

Third, recidivism reduction studies tend to use variables identified and operationalized by researchers as a starting place. As a result, the firsthand perspectives of individuals with SMD are largely eclipsed. Kelly Hannah-Moffat takes issue with this approach, arguing “categorical definitions of risk/need discredit, exclude, and co-opt alternative interpretations of offender needs… Individuals are positioned as potential recipients of predefined services, rather than as active agents involved in processes of self-identifying needs” (2005:43). As a result, building a more holistic theory of carceral involvement for those with SMD requires complementing (or countering) expert perspective with the experiences of these individuals.

Alternative conceptualizations of carceral involvement for individuals with SMD

Several alternative theoretical orientations for understanding criminal subjects and the overrepresentation of certain groups in carceral systems exist. For example, life course theory and longitudinal approaches help clarify the relationship of life experiences to risk of incarceration (Sampson and Laub 1995). Eric Silver (2006) has advocated for the application of these approaches, as well as other criminological theories (social stress, social control, rational choice, and social disorganization) to the study of the relationship between mental illness and violence. Yet, the application of these theories to the relationship between mental illness and incarceration more broadly is scant (Fisher et al. 2006) and, in our view, hindered by a lack of in-depth longitudinal and qualitative research with this population. Indeed, in the absence of such data, some have come to view the unobserved life experiences of these individuals as “unobservable” (e.g., Frank and McGuire 2011).

Another potential theoretical avenue is the application of public health scholarship that theorizes drivers of engagement in risky behavior (Barrenger and Draine 2013). For example, Rhodes’ (2009) risk environment framework may be a helpful complement to individually focused medical and criminological theories. The risk environment framework emphasizes the role of social circumstances and the environment in shaping engagement in harmful behaviors (e.g., drug use). Despite medicalized perceptions of individuals with SMD as criminalized patients and aside from studies of treatment expenditures, public health and socio-structural lenses have not been used to understand engagement in criminal behavior among this population or their carceral representation. Given the lack of empirical validity of the criminalized patient orientation and the limited score of the risk/need offender orientation, such alternative orientations may shed light on this phenomenon.

This study seeks to move beyond the theoretical orientations of the criminalized patient and the high risk/need offender. Adding to a small body of research that centers the carceral experiences of individuals with SMD (e.g., Jacobs and Giordano 2018; Kriegel 2019; Watson et al. 2008; Wilson 2013), the study seeks a holistic understanding of risk anchored by the first-hand experiences and self-articulated needs of individuals with SMD. Contending these perspectives contribute to a richer conceptualization of the factors and processes contributing to incarceration, we look beyond risk factors perceived by experts as modifiable or intervenable and instead consider individual, structural, or historical factors, as indicated by interviewee narratives. By maintaining this holistic and inductive approach, the analysis contributes to theory building while also opening the potential for new connections to alternative theoretical frameworks. In sum, the study attempts to address a previous empirical void, while providing theoretical guidance grounded in participant experiences.

Methods

This study seeks to bring to light the circumstances under which individuals with SMD are arrested, documenting factors and processes illustrated by their testimonies. While other studies have utilized deductive methods to analyze reports of arrest (e.g. Junginger et al. 2006; Peterson et al. 2010; 2014), they use expert-informed, top-down categories to define risk factors and are decontextualized from other life circumstances. This study addresses this gap by using an inductive approach, which highlights factors most salient to participants, and investigating current and past circumstances, which contextualizes and allows risk to be temporally proximal, distal or cumulative. To achieve these aims, we use two analytic approaches- Interpretive Phenomenology (Benner 1994) and Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz 2006). Each approach is operationalized below as we describe the study site, data, analysis, and sample.

The first author conducted fieldwork in a large social service organization. Located in the urban center of a large West Coast city, the organization provides services to a significant proportion of the city’s indigent adults with SMD. Services are largely publicly funded. Participants for the study were recruited from a program within this organization, which provides services to individuals with SMD who are also carcerally-involved (i.e. under community supervision or with histories of repeated incarceration). The city where this organization is situated has a rich social service infrastructure and an openness to alternative sentencing. The city’s embrace of the “rehabilitative model” in some ways presents an optimal case, one in which participants have greater access to social services than in communities where a punitive ethos dominates or services are lacking. However, an extreme shortage of affordable housing also makes this city an environment in which homelessness is a major vulnerability for socioeconomically precarious groups.

Data include interviews with “clients” and “staff,” and researcher memos containing meta-observations from interviews. We drew on data from staff interviews and memos primarily to contextualize and triangulate data gleaned from client interviews. Memos were also used to analyze the first author’s role in the research process. We used purposeful (typical and criterion) sampling strategies (Palinkas et al. 2015), and criteria for “client” participants required having a SMD and at least two unique arrest experiences, with at least one occurring within the past two years. The sample size was selected to permit detailed analysis of individual experiences, while facilitating the connection of these details to the broader life history and contexts within and across interviewees. Interviews moved from open-ended, focused, and ultimately analytic questions (Charmaz, 2006). Acknowledging the power imbalance inherent to the researcher/interviewee relationship, the first author made efforts to create a sense of reciprocity and to diminish imbalance (Mills et al. 2008). Interviews averaged one hour and fifteen minutes, were recorded, and transcribed.

The sample is demographically similar to the local county jail population (see Table 1). The diagnostic profile of participants also reflects that of the organization within which fieldwork was conducted, with the exception of one atypical participant (Celia)ii who reported having no known diagnosis. One interviewee was excluded from the analysis due to difficulty attuning during the interview, bringing the total sample to 19 clients and 4 staff participants (n = 23).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Social Indictors (count, unless otherwise indicated; n=19)

| Male | 15 | Family contact: | Substantial | 6 | Housing: | S RO Hotel | 9 |

| Female | 4 | Some | 11 | Supported/drug treatment | 5 | ||

| Median Age (range) | 45 (30–66) | None | 2 | Apartment/house | 3 | ||

| Black/African American | 5 | Primary support: | Friend, partner | 8 | None | 2 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 | Family | 5 | Diagnosis: | Schizophrenia | 8 | |

| White | 4 | Service Provider | 4 | Schizoaffective/Bipolar | 6 | ||

| More than one race/ethnicity | 4 | None | 2 | Major Depression | 2 | ||

| Native American | 1 | Receives public income support | 18 | Other | 3 | ||

| Straight | 15 | ||||||

| Gay or Bisexual | 4 | ||||||

We analyzed transcripts using Dedoose, qualitative data analysis software. Using the Grounded Theory technique of line-by-line coding and drawing from phenomenological tradition, we first used codes to stay close to participant descriptions of arrest events, including both material elements and ascribed meanings. We then used memoing, focused coding, and theoretical coding. Throughout this process we moved back and forth from line by line detail to the overarching interviewee’s history, expressed identity, and current experience, noting themes across levels. Subsequently, we used tables to organize data within and across cases, facilitating identification of patterns against which we could test thematic observations (Miles and Huberman 1994). We engaged in reflexive practices throughout data collection and analysis (Charmaz 2006). Finally, we utilized researcher triangulation, discussing and interpreting a sub-sample of codes and themes with two other researchers.

Results

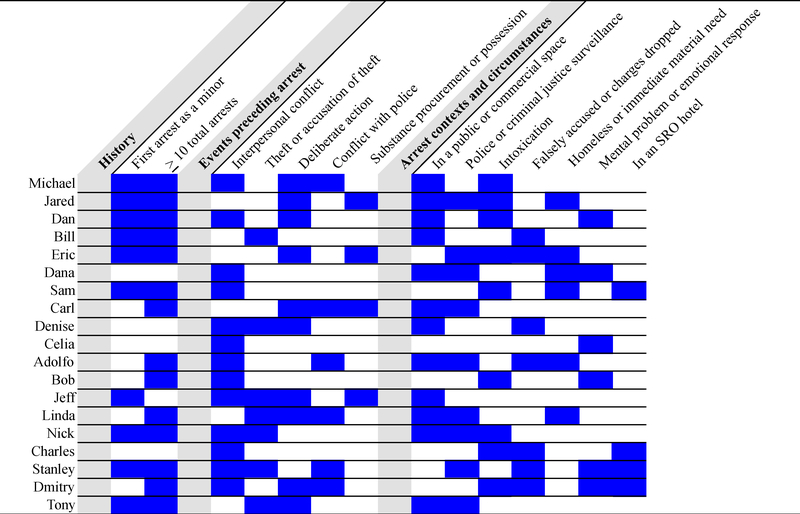

Below, findings are presented according to four themes spanning participants’ arrest narratives and life experiences- institutional entrenchment and arrest, mental status and arrest, conflict and arrest, and socio-economic marginality and arrest. These themes reflect respondents arrest narratives, which characterized the events immediately preceding arrest and contexts under which arrests occurred. As relevant, testimony pertaining to past life experiences are presented to permit an understanding of interviewees’ social circumstances (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Common historical factors, arrest events, and arrest contexts by interviewee

“My life has been corrupted”: Institutional entrenchment and arrest

Interviewees discussed frequent arrests and long histories of carceral involvement, with the majority reporting over ten arrests. Arrests became a common aspect of life for those cycling in and out of custody, leading to a normalization of carceral involvement. Those with frequent arrests described their experiences with insouciance, stating “once in a while I’ll get arrested,” “I get these [arrest] incidents confused,” or “[I get arrested] just for a day or so, here or there. Not too much.” The minority of interviewees with few experiences described their arrest as “a shock” or “the worst thing that ever happened.” Those frequently returning to custody demonstrated carceral expertise, explaining in great detail the procedures of arrest and the physical conditions of the jails in which they had been detained, and mentioning by name the police, correctional officers, and jail staff with whom they interacted. Such familiarity also translated into recognition by police on the streets or by jail staff upon re-arrest. As interviewees explained, chronic system involvement was like a “jacket” worn within and outside jail walls.

Most interviewees reported a first arrest in adolescence. For these participants, involvement with the juvenile system became one stop in a series of institutional experiences, spatially and socially disconnecting them from residential contexts as they cycled from one juvenile facility to another. As Nick described:

When you’re in juvenile hall they send you to the county that you live in, and that county sent me to that group home in [city]. That county also sent me to a group home in [second city]. They sent me to [third city] to a boys’ home. And then they sent me… to a boys’ home in [fourth city].

Such cycling occurred between and within youth justice and mental health systems, and eventually their parallel adult systems. Eric, a white man in his early 30’s with bipolar disorder, described his system trajectory, stating, “I was in a mental health facility and I ran away from it. I think I was 14 or 15 [years old]. So they put me in a juvenile detention facility because I refused to go back [to the mental health facility].” Aligning with the argument that mental health services alone fail to prevent incarceration (Skeem et al. 2011), arrest experiences occurred during periods of mental health service receipt, with one-third of interviewees describing arrest events concurrent with participation in treatment. Thus, youth and adult psychiatric and justice systems intersected and overlapped, and access to mental health services did not preclude arrest. Staff interviewees illustrated the spinning of this institutional web, often detailing intersystem collaboration as a key component to their work.

Juvenile involvement not only facilitated adult carceral involvement by creating institutional pathways to adult systems, but also via exposure to traumatic experiences in early detainment that promoted adaptive responses of defensiveness and violence. Nick, a Salvadoran man in his 50s, reported his first arrest was for “incorrigible truancy.” Offering clarification, he explained he wasn’t “antisocial,” he just preferred “riding motorcross bikes” to attending school. Juvenile hall, however, had “taught [him] violence.” Nick described his first experience in detainment:

[Another youth] was watching TV and … I asked him, “do you want to watch this?” And he said, “no.”… I put [a show] on that he wanted to watch. And then … this other guy, bigger, comes up and grabs me by the throat, and tells me: “If you ever change that channel again, I’m gonna’ break your Adam’s apple.” So, I take it that I did it out of fear… I … grabbed the pool stick, and broke it over his head… I found out, I think, that I liked [violence]. I seen how effective it could be. You know, the use of violence, and doing it so quick, and weapons, that it actually started motivating me.

Similarly, Tony, a middle-aged man of Chinese, Polish, and Latino descent explained, “My life has been corrupted by going to jail and prison.” He went on to describe how juvenile hall contributed to this corruption.

Tony: Well, looking back I would say [juvenile hall] built the foundation to become not only a future criminal, but a future institutionalized person.

Researcher: How so?

Tony: The influences… and the dynamic with the us versus them... with the police and the counselors and the prison guards and jail guards. [Juvenile hall is] a small example of the bigger world of jail...Eventually, it gets ingrained in you. Now, if I walk down the street and a cop rolls by, he can see instantly; I try not to look like a person that’s been to prison or jail.

Tony implicated the violence and systems of stratification learned via early and extensive institutional involvement and associated deprivation of educational and employment opportunities in dramatically shaping his life. Thus, these early institutional experiences contribute to the accumulation of risk, becoming embodied and shaping trajectories, identities, and behaviors.

“It isn’t usually wise”: Mental status and arrest

Three mental statuses characterized interviewees’ arrest experiences – deliberation, intoxication, and, less commonly, psychiatric symptoms. Most frequently, interviewees described taking logical, deliberate actions in the events preceding arrest. Deliberate actions included premeditation, acts of arrest avoidance, and choosing to surrender or cooperate with authorities. Tony described premeditation in the events preceding his last arrest, pragmatically explaining: “I had some people that I owed some money to, and so I went to [street name] and I thought I was going to get over on a tourist or something.” While attempting to steal a camera out of a car, Tony realized he had gained the attention of police. He initially tried to avoid apprehension by leaving the scene, but ultimately cooperated, explaining “it isn’t usually wise to resist [arrest].” Eric reported his last arrest occurred after he relapsed and used crack cocaine, violating the terms of his community supervision and residential treatment program. He explained,

I could’ve skipped [court], but I don’t want to have a warrant. So, I showed up to court and [I knew] they were going to remand me … but I just wanted to get it over with. I showed up that Thursday and they put me back into custody, which I figured they would.

Eric informed the first author that he had planned ahead, bringing his psychotropic medications with him to court in the hopes he would be allowed to bring them in the jail once remanded.

While Tony and Eric expressed agency and logical thinking in terms of surrender or cooperation, others deliberately attempted to avoid arrest. Michael, a middle-aged African American man, illustrates intentional arrest avoidance below.

I wanted to make [the police] chase me… I used to fuck with the police. I hated them with a passion. It was fun fucking with them. I have some police that used to hang out with me on the corner, but I was like, ‘man, you can’t hang out with me here on the corner. You’re fucking up my business. I’m trying to sell dope and drink beers.’

Instead of isolated responses to incidents of criminalization, such conflictual relationships developed over time, a product of the “us versus them” dynamic Tony previously described.

Intoxication was the second most common mental status during arrests, with interviewees frequently discussing inebriation’s negative influence on conflict navigation and judgment. For Sam, an African American man in his late 50’s with major depression, substance misuse fueled interpersonal conflict and violence. He detailed what happened preceding his last arrest:

I was getting high with a female friend and we were smoking crack and drinking vodka and we got angry, and I ended up hitting her with the drawer from a dresser, and she got cut with a knife. I don’t know who called the police – somebody in the building. I was, at the time, in a program and I was living in a [single room occupancy hotel (SRO)].

In describing the circumstances leading to this arrest, Sam was surrounded by negative social influences, dependent on drugs, and “always trying to think of something to get some drugs, or to get some food, shelter…always scheming something.” He explained, “I couldn’t stop using drugs… I just couldn’t stop. I tried everything and, at that time, I’d been in a lot of programs and dropped [out of] rehabs.” Upon his last release from jail and after being prompted on multiple occasions to take psychotropic medications, he thought, “what can I lose if I [try] medication?” Sam reported the medications helped curb his drug use, suggesting a relationship between depression and his substance misuse.

In addition to conflict, substance misuse was often the backdrop for attempted theft. Nick, who previously described his experience in juvenile hall, illustrated the role of intoxication in promoting theft and enhancing the likelihood of detection and conflict during his last arrest.

I was arrested at some type of Home Depot…for being too intoxicated. Because that’s the only time I get arrested, ‘cause I get sloppy and don’t care who’s looking or how long I’m in a store. But, I think I got detained first by security in there, and we got into a little argument.

Nick viewed his substance use as facilitating his detection, but not as the root of his criminality. Easily disappointed in people and quick to anger, he explained he would “lose control until it’s too late… get so upset or angry, black out,” and drink or do drugs. “I don’t even know I’m doing [something illegal], like I’m a different person… I mean you always got control to some degree.” Nick suggested controlling or tolerating his emotions was difficult, promoting substance misuse and, in turn, arrest.

While interviewees such as Sam and Nick indicated the interconnectedness of intoxication and mental anguish, few directly discussed psychiatric symptoms as an independent component of their arrest experience. Only three individuals described symptoms or made a connection between symptoms and illegal activity. The first author asked Bob, one such participant, “What do you think was going on for you [when you were arrested]?” A Latino man in his late 40’s diagnosed with schizophrenia, Bob responded plainly: “I was going crazy.” He otherwise had a difficult time piecing together and conveying the events of his arrest. In sum, while deliberation was constrained by the circumstances of each interviewee, premeditation, cooperation or avoidance also indicate the degree to which most participants were agentic.

“And we got in a disagreement”: Conflict and arrest

Interpersonal conflict was among the most common precipitants of arrest. Of these conflicts, half occurred with an individual familiar to the interviewee (e.g., a friend, or partner). For some interviewees, navigating social dynamics was a general challenge. Nick, for example, reported constant disappointment with people, which in turn triggered his substance misuse and engagement in illegal activity. Generally, however, interpersonal conflict with members of the interviewee’s social network represented a moment during which relational dynamics reached a climactic moment of dysfunction. In particular, when substance misuse was involved, conflict negotiation became impaired.

Given social networks were often constituted by other individuals who faced similar social and economic challenges, such conflict seemed unavoidable. As suggested in previous research (Skeem et al. 2009), interviewees’ networks seemed concentrated with individuals who also possessed little social or human capital, facing addiction, health, or mental health problems; these kin were also “getting high” or acting “crazy.” Charles, one of the men who reported a misunderstanding with a girlfriend preceding his arrest, attributed his carceral involvement to a pattern of dating women “from programs,” explaining:

I’m not getting involved with anyone with severe mental health [problems]… Because this was the second time that I got together with someone with severe mental illness and this happened… I wish we had just kept it on the friend level. It was the drinking though. It happened while we were drinking.

Another interviewee explained plainly, “being around the wrong people, associating myself with the wrong people” made it hard to stay out of jail. Thus, conflict with partners and friends commonly preceded arrests, but is best understood within the broader social landscape of interviewees’ limited networks, substance misuse, and structural constraints on the ability to develop social skills.

With the exception of one incident, which involved what might be considered a “random act of violence,” interpersonal conflicts occurring between interviewees and strangers typically arose during attempted theft or after provocation. During thefts, participants described being intoxicated. Upon detection, an argument ensued with a store employee, resulting in the notification of police, and arrest. In contrast to conflicts with store employees, conflicts resulting from some kind of unsolicited provocation by a stranger did not involve substance misuse. Dana, a white woman in her late-30’s, diagnosed with bipolar disorder, had spent most of her adult life living on the streets. She described her experience of provocation.

There was a woman and she said, “You gotta get off my steps,” and I said, “Can you just wait a minute, so I can catch my breath?” ‘Cause I was homeless. And she started yelling, and then she started taking a picture of me. I’m a homeless person and she’s taking a picture of me with her camera. And I said, “You can’t do that. You’re not allowed to take pictures of me.” I started getting upset and then the cops came and arrested me.

Adolfo, a man of Latino and African American descent in his mid-30’s with schizophrenia, provides another example of such provocation. Below, he describes how a group of youth misidentified, followed him off a bus, and harassed him in the events leading to his arrest.

Adolfo: Yeah, they tried to [assault me]. They were trying to aggravate me. I had a hammer in my bag. I took out the hammer and told everyone to get back away from me. They were picking up rocks and throwing them at me...

Researcher: Why did you have the hammer in your bag?

Adolfo: I was homeless at the time and I could use it to open doors to apartment buildings and stuff.

Researcher: Was [the hammer] also for protection?

Adolfo: No.

Ultimately, for both Dana and Adolfo, the social status and material conditions of homelessness combined with perceptions of their defensive behavior as threatening to facilitate arrest.

Together, these results indicate interpersonal conflict, both with kin and strangers, is an important part of arrest narratives for individuals with SMD. In circumstances where conflict arose with members of social networks, the conflict occurred as part of a pattern of dysfunction. In some cases, alcohol or drugs compromised interviewees’ abilities to communicate, navigate dysfunction, or tolerate the other actor’s behavior; As one interviewee clearly asserted, “What makes it hard [to avoid arrest] is … using a drug with a person instead of using it alone.” Conflict occurring with strangers also unfolded dynamically, including provocation and defensive responses. The bases for such conflict extended beyond these dyadic interactions, stemming instead from limited social networks and socioeconomic exclusion.

“We get it bad”: Socio-economic marginality and arrest

Interviewees’ arrest experiences are more completely understood when placed in their economic circumstances and when discussed in relation to identity. Economic circumstances, marked by homelessness and neighborhood conditions concentrated with disadvantage, were commonly implicated in arrest narratives by contributing to stigma, triggering substance misuse, and evoking surveillance. As Dana and Adolfo’s experiences illustrate, the material conditions of homelessness and the social stigma attached to being homeless enhanced vulnerability to provocation. When asked what she thought made it hard for her to stay out of jail, Dana responded, “I think [homelessness] makes it a bit harder. Just because you don’t really have anywhere to go…you tend to draw bad attention to you and the cops come.” Nick, who had been arrested while intoxicated in Home Depot, experienced homelessness as a risk factor for substance use and, in turn, arrest. Released from jail late at night, he went “straight to the liquor store” in the absence of anywhere else to go.

Often housing interviewees and the sites of arrest, SRO hotels were spatial indicators of social worth, magnets for police surveillance, and negatively impacted mental health. Echoing findings from research describing these hotels as “mental health risk environments” (Knight et al. 2014), Tony explained, “[The SROs] are a wreck in and of themselves… really scumbag places, a bunch of corruption – weird, wacky stuff in there. It’s filthy. There are bed bugs. It’s a very low, low way.” Jared, a white man in his early 30s, who reported multiple psychiatric diagnoses, described the SRO hotel in which he lived after reentering the community from jail and its effect on his mental health:

The pest control is a joke…there was a chunk of my closet missing and my room was exposed to the interior of the building, which was full of mice. I would literally have acute panic attacks every day because I’d put on my shoe and mice would jump out. It literally led me to not be able to sleep because I could hear things in the walls. It led me to be psychotically delusional… To this day, I still hear things that aren’t there because of these mice.

Thus, the environmental conditions of “affordable housing” can be traumatogenic. Jared was also one of two interviewees whose last arrest occurred during a neighborhood police sweep. He explained, “The police just stopped everybody… throughout the [neighborhood] ... anybody who looks even slightly suspicious…[the police] do what’s called a ‘roundup.’ The jail was so packed that the booking was taking place outside and it took almost two days for me to be processed.” While Jared perceived his drug dependence as fueling his engagement in illegal activities, he also indicates his “suspicious” appearance and homelessness in an area of targeted policing facilitated detection. Ethnographic investigations support Jared’s observations of police targeting and territorial practice (Herbert 1997; Beckett and Herbert 2009).

Such circumstances provide meaning to Adolfo’s sentiment that “there were times when… going to jail was like a vacation.” In addition to triggering substance misuse and exacerbating mental health problems, for some interviewees social and economic marginality diminished motivation to avoid arrest or the substance misuse that facilitated arrest. Eric explained how housing instability both reduced his ability to avoid and his interest in avoiding arrest: “I’d get out [of jail] and get into a program, but those are only usually three to six months. Then you finish and you’re like, ‘what now?’” In the past, with few alternative opportunities and few reasons to abstain from substance misuse or criminal activity, Eric would recidivate. In contrast, when Eric and the first author spoke, he felt hopeful about his current ability to avoid relapse and re-arrest, explaining:

Now that I have my own place, it’s different. It’s on [street], so it’s not the Taj Mahal, but I’ve got it set up nice with my TV and my guitar. It’s very comfortable, so I actually feel like I have a home now… When I was homeless or in a program, I didn’t have anything. Now, I have a dog and an apartment. I have nice things. You don’t want to lose them. Before, I mean, I didn’t want to go to jail, but it wasn’t as big of a motivator to stay out. I mean, what did I have to lose? Sleeping on the street another night?

In the presence of living conditions that provide some quality of life, avoiding arrest and the changes Eric needed to make to do so became more desirable.

“Having a place to go,” as Eric put it, that would reduce involvement in illegal activity or arrest, not only pertained to housing but also spaces that would afford safety and structured daily activity. No participant reported an arrest that took place while participating in any kind of meaningful daily activity, and only two interviewees reported missing such activity as a result of an arrest. In contrast, when asked what might have helped them stay out of jail, more than half of all participants identified having a safe place to spend time or employment (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-reported criminogenic needs

| Criminogenic Need | Count* |

|---|---|

| Social Support | 12 |

| Daily activity/Work | 11 |

| Housing | 8 |

| Sobriety | 7 |

| Self/Maturity | 7 |

| Mental health care/Medications | 6 |

Including multiple responses per participant

Opportunities to develop the human capital necessary to escape marginality seemed absent from the lives of interviewees. Frequent and extended periods of early institutionalization deprived some interviewees of the ability to develop general life and employment skills. Tony, for example, reported a six-year period of desistance from crime, during which he gained the support of a spiritual community and managed to “get clean.” After “coming up on some really stressful things, [like] becoming a father and all that,” however, Tony relapsed and recidivated. He explained, “I missed a lot of life because of time in institutions, so a lot of things that people learned to do long ago for me is like brand new.” Thus, the low socioeconomic status many individuals with SMD experience (Frank and Glied 2006), appears to be at least partially maintained by institutional involvement and the accompanying deprivation of real-world learning opportunities for individuals entrenched in carceral systems.

In contrast, reporting little previous involvement with justice or psychiatric systems and prior financial stability, Celia was an atypical interviewee. A woman in her late 30s, Celia emigrated from Columbia ten years prior to our interview. Arrested after an argument with her husband, Celia described the criminogenic circumstances within which she found herself upon release from jail.

Researcher: Okay, and how was [the housing you were placed in after release from jail]?

Celia: Bad…Basically…I don’t do any drugs–and those hotels like that, everybody smokes, everybody is doing drugs. Yeah, it’s just kinda scary. And it is really dirty, smelly. The living conditions are bad, bad, bad, bad, bad.

When Celia and first author spoke, she was homeless, trying desperately to find housing and to regain custody of her daughter, both of which she’d lost during her detainment. Acting as a foil to other interviewees, Celia seemed swept up in both carceral and mental health systems, illustrating the powerful capacity of incarceration to spur swift downward socioeconomic mobility in the absence of significant social and human capital.

While Celia described relatively stable circumstances prior to her arrest, she was also made vulnerable to arrest and downward mobility by factors such as her limited English proficiency, which impaired her ability to communicate with police, and her gendered work as a homemaker. Indeed, aspects of identity, in addition to class and disability status, enhanced vulnerability.iii Men and women both discussed gendered aspects of arrest experiences. Three out of the four women described physical vulnerability to police during arrest. Dana explained, “I thought the guy police officer did it on purpose to make me, a woman, feel trapped.” Celia reported overwhelming fear when police raided her home, forcing her out of the shower at gunpoint. Male interviewees, with their generally longer carceral histories, saw arrest as partially motivated by gendered police bias. Dmitry, a man of Native American descent in his early 30’s, felt targeted, explaining:

Dmitry: Me and my girlfriend got in an argument ... She locked me outside of the room. I pounded [the door], even though she was twice my size literally... definitely twice my size at this point, but they had to remove one of us and, of course, who is at fault? Always the male; it always falls on the male.

Researcher: Do you know who called the police?

Dmitry: I did.

Researcher: And you called the police because she locked you out?

Dmitry: And was aggressive.

Despite an increase in the rate of dual arrests among the general population in intimate partner violence cases (DeLeon-Granados et al. 2006; Miller, 2001), these men felt they were automatically placed in the position of “perpetrator” and, in turn, more likely to be arrested.iv These data suggest that arrest experiences among those with SMD were gendered with women expressing a sense of physical vulnerability, and men feeling as though they were being discriminated against.

Sexual identity also placed interviewees in unique positions of vulnerability. Jeff, a Latino man in his early 30s, diagnosed with schizophrenia, described juvenile hall as “traumatic” and an experience uniquely shaped by his gay identity. Jeff’s early experiences of manipulation by staff in juvenile detention seemed to replicate later in life; he had been “kicked out” of a residential substance abuse program the day before we spoke. When the first author inquired about Jeff’s expulsion from the program, he relayed his experience being sexually harassed by a staff member and a failed attempt to address the issue with other staff at the program. Jeff saw the “structure and sobriety” of his residential program as key to avoiding arrest, and thus expressed a tense dependency on systems that he also experienced as abusive and homophobic. In contrast to class, gender and sexual identity, no interviewee perceived bias during arrest pertaining to his or her psychiatric diagnosis.v Ultimately, socio-structural factors and elements of identity, beyond disability status, shaped conditions for and experiences of arrest and institutional involvement.

Discussion

At a basic level, the arrest narratives of justice-involved individuals with SMD in this study commonly centered an illegal act, the accusation of an illegal act, or a community supervision violation. These individuals contextualized their carceral involvement in early institutionalization, varying mental states of deliberation and intoxication, interpersonal conflict, and life circumstances punctuated by socioeconomic marginality. In the remainder of this paper, we discuss study limitations, further unpack findings by paralleling participant perspectives against prior research claims, and provide three recommendations for future conceptualization of carceral involvement among individuals with SMD.

This study draws on self-report data from a small sample of carcerally-involved individuals with SMD. While first hand reports provide an invaluable perspective, interview data also have limitations. Findings capture the perspectives of those interviewed, which may change over time and in relationship to who is listening, and may or may not align with the perspectives of other observers. Although the qualitative study design is not intended to be statistically representative or generalizable, the sample does not appear biased toward lower risk or symptomatically less severe individuals; three-quarters of participants reported receiving either Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance, criteria for which are stringently determined by level of dysfunction. Furthermore, participants received services from a program that enrolls only individuals considered at significant risk of reincarceration. Finally, given the dynamic nature of SMD, degree of functioning at the time of interview may have little relevance to one’s condition at the time of arrest.

Despite this study’s limitations, the participant-informed approach taken here voices “competing needs claims” often “silenced in a risk/need logic” (Hannah-Moffat 2005:43), and can be used to inform theory and direct relevant and palatable interventions for reducing carceral involvement among this population. This approach allows a unique glimpse into the events and contexts surrounding arrests from the perspective of those most closely involved. In the absence of longitudinal and in-depth ethnographic work, this study’s illumination of the ways in which individual and socio-structural factors facilitate arrest is essential to theory development.

What can we learn about criminal justice involvement from individuals with SMD, and how does that relate to prior research? In this study, individuals described arrests as part of a longer arc of institutional involvement, often beginning prior to adulthood. These findings support previous research establishing the iatrogenic effects of juvenile justice involvement on risk of future criminality (Cullen, Jonson, and Nagin 2011; Dishion, McCord, and Poulin 1999; Gatti et al. 2009; Mulvey 2011), suggesting that early institutionalization may enhance this risk by blocking alternative opportunities (Sampson and Laub 1997) and negatively impacting self-perception (Link et al. 1989). These findings also support prior research indicating that early involvement and more intensive intervention are associated with future mental health and substance misuse problems, as well as criminality (Dishion, McCord, and Poulin 1999; McCord 1978; Spohn and Holleran 2002).

Second, we find individuals with SMD framed arrests as the direct result of some kind of illegal activity, and as commonly involving logical thought processes and/or substance misuse. No interviewee perceived bias during arrest pertaining to his or her psychiatric diagnosis. These findings support prior research indicating non-symptom related actions and substance misuse are common precipitants to arrest (Baillergeon et al. 2010; Bonta et al. 1998; Peterson et al. 2014), support findings from observational research indicating little difference in the outcomes of police encounters between individuals with and without SMD (Engel and Silver 2001), and support calls for the integration of rational choice theories to the study of criminal activity among this population (Silver, 2006). Most interviewees were not simply objects or victims, subject to the whims of their symptomatology or police discrimination, as advocate practitioners of the criminalized patient approach imply.

Third, social conflict appears here as a salient precipitant of arrest for individuals with SMD. Conflict with members of social networks were characterized as a part of a larger dysfunctional relationship. Conflict with strangers seemed to extend beyond these dyadic interactions, stemming instead from limited social capital and socioeconomic exclusion. This finding supports research that positions interpersonal conflict (Silver 2002) and impaired social networks (Silver and Teasdale 2005; Skeem et al. 2009) as risk factors for arrest for those with SMD, indicating the applicability of social stress orientations to understanding engagement in crime for this population (Silver, 2006).

Fourth, socio-structural forces of marginalization and elements of identity, beyond disability status, shaped conditions for and experiences of arrest and institutional involvement. This finding supports research that places social and economic marginality, demarcated by stigma, homelessness, joblessness and surveillance (Beckett and Herbert 2009; Hiday 1995; Silver 2000; Watson et al. 2008) in the black box of arrest risk for this population. Together, results indicate risk of carceral involvement stems not from any single factor or event. Risk was accumulative, unfolding via complex interactions and social dynamics, and enhanced by economic and social marginalization produced by structural forces of institutionalization, substance use criminalization, inadequate access to quality affordable housing, and surveillance.

The participant-informed approach taken here promotes a new orientation for understanding those with SMD, moving from criminalized patients or high risk/need offenders to risk-exposed agents. As risk-exposed agents, these individuals face numerous factors, individual and sociostructural, promotive of carceral involvement. Many of these factors accrue over time, in part due to the iatrogenic repercussions of institutionalization. Simultaneously, the risk-exposed agent is agentic in that their actions cannot be reduced to the manifestation of psychiatric symptoms. In turn, the conceptualization of the risk exposed agent contradicts that of the criminalized patient, which argues symptoms lead directly to arrest and that, in the absence of mental health treatment, individuals with SMD are at enhanced risk of arrest. Instead, the risk-exposed agent commonly experiences arrest due to criminal activity that is deliberate or in response to interpersonal conflict, and amidst receipt of behavioral health services. When implicated, psychiatric symptoms are most often indirectly connected to arrest, contributing over time to social and economic exclusion or promoting substance misuse.

The risk-exposed agent orientation aligns, to some degree, with the high risk/need offender approach, which suggests symptoms directly contribute to arrest for a small proportion of individuals with SMD (Peterson et al. 2010). Findings from this study, however, indicate that understanding carceral involvement among those with SMD, including the role of psychiatric diagnoses, require looking beyond individual-level and modifiable risk factors preceding recidivism. The risk-exposed agent orientation highlights the role of experiences such as early institutionalization and the interaction between SMD and socioeconomic marginalization, suggesting individual risk and representation be understood both across the life course and contextually situated (Silver, 2006).

In sum, the risk-exposed agent orientation necessitates three conceptual shifts for understanding carceral involvement for individuals with SMD. Risk is accumulative and unfolding through complicated multivariate processes and dynamic interactions; it is not easily reduced to independent variables examined at a single moment in time and absent consideration of contextual preconditions. As Frank and McGuire suggest, “the full effect of mental illness on crime goes beyond a contemporaneous causal relation” (2010:3); SMD itself manifests dynamically, at one moment in time relating directly to arrest, at other moments interacting with general criminogenic risk factors, and having varying effects on opportunities and relationships over time.

Secondly, findings highlight the importance of viewing carcerally-involved individuals with SMD as more than their diagnostic labels. Defining these individuals as a “high risk population” based on diagnostic status may actually work to obscure other factors relevant to arrest (i.e., relational problems, inadequate access to housing, policies that criminalize substance misuse), while simultaneously reifying stigmatizing notions of inherent and totalizing deviance. To better understand their system involvement, people with SMD should instead be recognized as holding intersectional identities (i.e., class, gender, sexuality, and ethnoracial) in addition to disability status, which in combination influence exposure to risk factors.

Finally, findings indicate that risk is not individually determined, and suggest criminologists complement life course approaches with multi-level models of risk, such as the risk environment framework (Rhodes, 2009). The risk-exposed agent orientation calls for research that situates the individual in a broader context, examining ways in which policies and interventions can diminish individual- and socio-structural risk factors for carceral involvement and enhance quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Deborah Lustig, David Minkus, Christine Trost, and the graduate fellows at the University of California’s Institute for the Study of Societal Issues, who provided invaluable encouragement and feedback on the manuscript. We also thank Ana Flores, who provided editorial support.

Funding

This research has been financially supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Award T32AA007240) and the Institute for the Study of Societal Issues’ Center for Research on Social Change at the University of California, Berkeley. The content solely reflects the ideas of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of these sponsors.

Biography

LEAH A. JACOBS is an Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh. She studies socio-structural influences on criminal justice involvement and re-entry outcomes, particularly for individuals with mental and substance use disorders. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Welfare from the University of California, Berkeley.

MEG PANICHELLI is an Assistant Professor in the Undergraduate Social Work Department at West Chester University of PA. Her research focuses on the intersections of drug use, sex trade, and mass criminalization. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Work from Portland State University.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no financial interest or benefit that has arisen from this research. We know of no other conflicts of interest.

SMD commonly includes major depressive and depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS), bipolar disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and psychotic disorder NOS (APA, 2000; Kessler et al., 2005). I make no claim as to the etiology, validity or reliability of these diagnoses.

To maintain confidentiality, pseudonyms are used.

While one interviewee suggested the racial bias of a judge facilitated his entry into the juvenile justice system, no clear perceived pattern in arrest experiences emerged by ethnoracial identity. A separate analysis of interviewees’ detainment experiences (manuscript in preparation) did vary by ethnoracial identity, with interviewees describing jail as highly stratified along ethnoracial lines.

California has preferential arrest and primary aggressor policies. According to these policies, in intimate partner violence (IPV) situations the “dominant aggressor” should be arrested (CA Penal Code 13701; Zelcer, 2014). There is some indication that these policies increase the probability of dual arrests (Miller, 2001; Zelcer, 2014), although the degree to which they bias arrests in favor of male or female perpetrators remains unclear (for a review, see Hirschel et al., 2008). Research to date does, however, suggest that the circumstances of the arrest and characteristics of the individuals involved inform who is arrested (Hirschel et al., 2008). Further research is required to ascertain whether men with SMD are actually more likely to be perceived as a perpetrator by police and, if so, more likely to be independently charged.

Interviewees did experience differential treatment by psychiatric status while in jail.

References

- Abramson Marc F. 1972. “The Criminalization of Mentally Disordered Behavior: Possible Side-Effect of a New Mental Health Law.” Psychiatric Services 23(4):101–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.23.4.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen Francis A. 1981. The Decline of the Rehabilitative Ideal: Penal Policy and Social Purpose. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews Donald A. and Bonta James. 2010. “Rehabilitating Criminal Justice Policy and Practice.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 16(1):39. doi: 10.1037/a0018362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon Jacques, Penn Joseph V., Knight Kevin, Amy Jo Harzke Gwen Baillargeon, and Becker Emilie A. 2010. “Risk of Reincarceration among Prisoners with Co-Occurring Severe Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 37(4):367–74. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0252-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrenger Stacey L. and Draine Jeffrey. 2013. “‘You Don’t Get No Help’: The Role of Community Context in Effectiveness of Evidence-Based Treatments for People with Mental Illness Leaving Prison for High Risk Environments.” American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 16(2):154–78. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2013.789709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine and Herbert Steve. 2009. Banished: The New Social Control in Urban America. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benner Patricia. 1994. Interpretive Phenomenology: Embodiment, Caring, and Ethics in Health and Illness. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer Herbert. 1971. “Social Problems as Collective Behavior.” Social Problems 18(3):298–306. doi: 10.2307/799797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonta James, Law Moira, and Hanson Karl. 1998. “The Prediction of Criminal and Violent Recidivism among Mentally Disordered Offenders: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 123(2):123–42. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonta James, Rugge Tanya, Scott Terri-Lynne, Bourgon Guy, and Yessine Annie K. 2008. “Exploring the Black Box of Community Supervision.” Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 47(3):248–70. doi: 10.1080/10509670802134085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cloyes Kristin G., Wong Bob, Latimer Seth, and Abarca Jose. 2010. “Time to Prison Return for Offenders With Serious Mental Illness Released From Prison: A Survival Analysis.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 37(2):175–87. doi: 10.1177/0093854809354370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen Francis T., Jonson Cheryl Lero, and Nagin Daniel S. 2011. “Prisons Do Not Reduce Recidivism: The High Cost of Ignoring Science.” The Prison Journal 91:48–65. doi: 10.1177/0032885511415224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon-Granados William, Wells William, and Binsbacher Ruddyard. 2006. “Arresting Developments: Trends in Female Arrests for Domestic Violence and Proposed Explanations.” Violence Against Women 12(4):355–71. doi: 10.1177/1077801206287315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion Thomas J., McCord Joan and Poulin François. 1999. “When Interventions Harm: Peer Groups and Problem Behavior.” American Psychologist 54(9):755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditton Paula M. 1999. Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Draine Jeffrey, Salzer Mark S., Culhane Dennis P., and Hadley Trevor R. 2002. “Role of Social Disadvantage in Crime, Joblessness, and Homelessness Among Persons With Serious Mental Illness.” Psychiatric Services 53(5):565–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel Robin Shepard and Silver Eric. 2001. “Policing Mentally Disordered Suspects: A Reexamination of the Criminalization Hypothesis*.” Criminology 39(2):225–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00922.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson Steven K., Rosenheck Robert A., Trestman Robert L., Ford Julian D., and Desai Rani A. 2008. “Risk of Incarceration Between Cohorts of Veterans With and Without Mental Illness Discharged From Inpatient Units.” Psychiatric Services 59(2):178–83. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel Seena and Danesh John. 2002. “Serious Mental Disorder in 23 000 Prisoners: A Systematic Review of 62 Surveys.” The Lancet 359(9306):545–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher William H., Silver Eric, and Wolff Nancy. 2006. “Beyond Criminalization: Toward a Criminologically Informed Framework for Mental Health Policy and Services Research.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33(5):544–57. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0072-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault Michel. 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, NY: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Richard G. and Glied Sherry A. 2006. Better But Not Well: Mental Health Policy in the United States Since 1950. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Richard G. and McGuire Thomas G. 2011. “Mental Health Treatment and Criminal Justice Outcomes” Pp. 167–207 in Controlling Crime: Strategies and Tradeoffs. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti Uberto, Tremblay Richard E., and Vitaro Frank. 2009. “Iatrogenic Effect of Juvenile Justice.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50(8):991–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah-Moffat Kelly. 1999. “Moral Agent or Actuarial Subject:: Risk and Canadian Women’s Imprisonment.” Theoretical Criminology 3(1):71–94. doi: 10.1177/1362480699003001004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah-Moffat Kelly. 2005. “Criminogenic Needs and the Transformative Risk Subject: Hybridizations of Risk/Need in Penality.” Punishment & Society 7(1):29–51. doi: 10.1177/1462474505048132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert Steven Kelly. 1997. Policing Space: Territoriality and the Los Angeles Police Department. U of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hiday Virginia Aldige. 1995. “The Social Context of Mental Illness and Violence.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36(2):122–37. doi: 10.2307/2137220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiday Virginia Aldige and Burns Padraic J. 2010. “Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System” Pp. 478–98 in A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschel JD (2008) Domestic violence cases: What research shows about arrest and dual arrest rates. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Leah A. and Giordano Sequoia N. J. 2018. “‘It’s Not Like Therapy’: Patient-Inmate Perspectives on Jail Psychiatric Services.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 45(2):265–75. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0821-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junginger John, Claypoole Keith, Laygo Ranilo, and Crisanti Annette. 2006. “Effects of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Abuse on Criminal Offenses.” Psychiatric Services 57(6):879–82. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, Manderscheid RW, Rosenheck RA, Walters EE, and Wang PS 2001. “The Prevalence and Correlates of Untreated Serious Mental Illness.” Health Services Research 36(6 Pt 1):987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight Kelly R., Lopez Andrea M., Comfort Megan, Shumway Martha, Cohen Jennifer, and Riley Elise D. 2014. “Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Hotels as Mental Health Risk Environments among Impoverished Women: The Intersection of Policy, Drug Use, Trauma, and Urban Space.” International Journal of Drug Policy 25(3):556–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegel Liat S. 2019. “Stranger Support: How Former Prisoners with Mental Illnesses Navigate the Public Landscape of Reentry.” Health & Place 56:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H. Richard. 2015. “Does Deinstitutionalization Cause Criminalization?: The Penrose Hypothesis.” JAMA Psychiatry 72(2):105–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G., Cullen Francis T., Struening Elmer, Shrout Patrick E., and Dohrenwend Bruce P. 1989. “A Modified Labeling Theory Approach to Mental Disorders: An Empirical Assessment.” American Sociological Review 54(3):400–423. 10.2307/2095613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz Fred E. 2006. “Psychiatric Hospital Capacity, Homelessness, and Crime and Arrest Rates*.” Criminology 44(1):45–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCord Joan. 1978. “A Thirty-Year Follow-up of Treatment Effects.” American Psychologist 33(3):284–89. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.33.3.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic David. 2007. Mental Health and Social Policy: Beyond Managed Care. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Miles Matthew B. and Huberman A. Michael. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Susan L. 2001. “The Paradox of Women Arrested for Domestic Violence: Criminal Justice Professionals and Service Providers Respond.” Violence Against Women 7(12):1339–76. doi: 10.1177/10778010122183900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills Jane, Bonner Ann, and Francis Karen. 2008. “The Development of Constructivist Grounded Theory.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(1):25–35. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan John and Skeem Jennifer L. 2014. “Risk Redux: The Resurgence of Risk Assessment in Criminal Sanctioning.” Federal Sentencing Reporter 26:158–66. doi: IO.I525/fsr.2014.26-3.145. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey Edward P. 2011. Highlights From Pathways to Desistance: A Longitudinal Study of Serious Adolescent Offenders. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey Edward P. and Schubert Carol A. 2017. “Mentally Ill Individuals in Jails and Prisons.” Crime and Justice 46(1):231–77. doi: 10.1086/688461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas Lawrence A., Horwitz Sarah M., Green Carla A., Wisdom Jennifer P., Duan Naihua, and Hoagwood Kimberly. 2015. “Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42(5):533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson Jillian, Skeem Jennifer L., Hart Eliza, Vidal Sarah, and Keith Felicia. 2010. “Analyzing Offense Patterns as a Function of Mental Illness to Test the Criminalization Hypothesis.” Psychiatric Services 61(12):1217–22. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson Jillian K., Skeem Jennifer, Kennealy Patrick, Bray Beth, and Zvonkovic Andrea. 2014. “How Often and How Consistently Do Symptoms Directly Precede Criminal Behavior among Offenders with Mental Illness?” Law and Human Behavior 38(5):439–49. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins Seth J. 2011. “Does Transinstitutionalization Explain the Overrepresentation of People with Serious Mental Illnesses in the Criminal Justice System?” Community Mental Health Journal 47(6):716–22. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9420-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Steven and Stoll Michael A. 2013. Why Are So Many Americans in Prison? Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes Tim. 2009. “Risk Environments and Drug Harms: A Social Science for Harm Reduction Approach.” International Journal of Drug Policy 20(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche Georg and Kirchheimer Otto. 1939. Punishment and Social Structure. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell Emma and Carlton Bree. 2013. “Pathways, Race and Gender Responsive Reform: Through an Abolitionist Lens.” Theoretical Criminology 17(4):474–92. doi: 10.1177/1362480613497777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J. and Laub John H. 1997. “A Life Course Theory of Cumulative Disadvantage and the Stability of Delinquency” Pp. 133–61 in Developmental theories of crime and delinquency, Advances in criminological theory. Piscataway, NJ, US: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Segal Steven P. and Jacobs Leah A. 2013. Deinstitutionalization. NASW Press and Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton Lori. 2015. “Penal Subjectivities: Developing a Theoretical Framework for Penal Consciousness.” Punishment & Society 17(1):114–36. doi: 10.1177/1462474514548790 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silver Eric. 2000. “Race, Neighborhood Disadvantage, and Violence Among Persons with Mental Disorders: The Importance of Contextual Measurement.” Law and Human Behavior 24(4):449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver Eric. 2002. “Mental Disorder and Violent Victimization: The Mediating Role of Involvement in Conflicted Social Relationships*.” Criminology 40(1):191–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00954.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silver Eric and Teasdale Brent. 2005. “Mental Disorder and Violence: An Examination of Stressful Life Events and Impaired Social Support.” Social Problems 52(1):62–78. doi: 10.1525/sp.2005.52.1.62 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silver Eric. 2006. Understanding the Relationship between Mental Disorder and Violence: The Need for a Criminological Perspective. Law and Human Behavior 30(6):685–706. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9018-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Jonathan. 2013. “The Return of the Medical Model: Disease and the Meaning of Imprisonment from John Howard to Brown v. Plata.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 48:217–56. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Jonathan. 2014. Mass Incarceration on Trial: A Remarkable Court Decision and the Future of Prisons in America. New Press, The. [Google Scholar]

- Sisti Dominic A., Segal Andrea G., and Emanuel Ezekiel J. 2015. “Improving Long-Term Psychiatric Care: Bring Back the Asylum.” JAMA 313(3):243–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem Jennifer, Jennifer Eno Louden Sarah Manchak, Vidal Sarah, and Haddad Eileen. 2009. “Social Networks and Social Control of Probationers with Co-Occurring Mental and Substance Abuse Problems.” Law and Human Behavior 33(2):122–35. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9140-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem Jennifer L., Manchak Sarah, and Peterson Jillian K. 2011. “Correctional Policy for Offenders with Mental Illness: Creating a New Paradigm for Recidivism Reduction.” Law and Human Behavior 35(2):110–26. doi: 10.1007/s10979-010-9223-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spohn Cassia and Holleran David. 2002. “The Effect of Imprisonment on Recidivism Rates of Felony Offenders: A Focus on Drug Offenders*.” Criminology 40(2):329–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00959.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]