Abstract

Background

Prognostic factors are lacking in cardiac sarcoidosis (CS), and the effects of immunosuppressive treatments are unclear.

Objectives

To identify prognostic factors and to assess the effects of immunosuppressive drugs on relapse risk in patients presenting with CS.

Methods

From a cohort of 157 patients with CS with a median follow-up of 7 years, we analysed all cardiac and extra-cardiac data and treatments, and assessed relapse-free and overall survival.

Results

The 10-year survival rate was 90% (95% CI, 84–96). Baseline factors associated with mortality were the presence of high degree atrioventricular block (HR, 5.56, 95% CI 1.7–18.2, p = 0.005), left ventricular ejection fraction below 40% (HR, 4.88, 95% CI 1.26–18.9, p = 0.022), hypertension (HR, 4.79, 95% CI 1.06–21.7, p = 0.042), abnormal pulmonary function test (HR, 3.27, 95% CI 1.07–10.0, p = 0.038), areas of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance (HR, 2.26, 95% CI 0.25–20.4, p = 0.003), and older age (HR per 10 years 1.69, 95% CI 1.13–2.52, p = 0.01). The 10-year relapse-free survival rate for cardiac relapses was 53% (95% CI, 44–63). Baseline factors that were independently associated with cardiac relapse were kidney involvement (HR, 3.35, 95% CI 1.39–8.07, p = 0.007), wall motion abnormalities (HR, 2.30, 95% CI 1.22–4.32, p = 0.010), and left heart failure (HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.12–4.45, p = 0.023). After adjustment for cardiac involvement severity, treatment with intravenous cyclophosphamide was associated with a lower risk of cardiac relapse (HR 0.16, 95% CI 0.033–0.78, p = 0.024).

Conclusions

Our study identifies putative factors affecting morbidity and mortality in cardiac sarcoidosis patients. Intravenous cyclophosphamide is associated with lower relapse rates.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multi-system granulomatous disease of unknown origin with an overall prevalence from 10 to 20 per 100,000 in white American and European patients to 35 per 100,000 in African American patients [1–3]. Clinically manifest cardiac involvement—known as cardiac sarcoidosis (CS)—occurs in 5% to 11% [4–6] whereas cardiac involvement was found in 25% of patients with sarcoidosis on autopsies [7, 8]. Such findings are consistent with data using late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [9, 10]. Between 16% and 35% of patients presenting with complete atrioventricular block [11, 12] or ventricular tachycardia of unknown etiology [12–14] have previously undiagnosed CS. Core left ventricular biopsies at the time of left ventricular assist device implantation found undiagnosed CS in 3.4% of patients [15], and 3% of explanted hearts had undiagnosed CS [16]. Congestive heart failure is a common presenting feature, as is sudden death. More rarely, CS has been associated with atrial arrhythmias and valvulopathy, coronary vasculitis, acute myocarditis, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy [17].

Cardiac involvement has been reported to account for 25% of all deaths from sarcoidosis in the United States and 85% in Japanese series [7]. There is controversy as to the prognosis of patients with clinically silent CS. In patients with clinically manifest disease, the extent of left ventricle dysfunction has been reported as a predictor of survival [18–24]. Despite the lack of randomized controlled trials, the use of moderate to high dose glucocorticosteroids is widely accepted [23–28], with the highest quality data related to atrioventricular block [18], left ventricular dysfunction and ventricular arrhythmias [6, 25–27]. Immunosuppressant are used as a second-line agent in refractory cases of CS and/or if there are significant steroid side effects [4, 29].

In this retrospective study of a large cohort of CS patients with a long follow up, we aimed to: 1) identify baseline prognostic factors influencing overall survival and relapses; and 2) assess the effects of immunosuppressive drugs on relapse risk.

Methods

Patients

Data from 690 patients with systemic sarcoidosis diagnosed and followed in a single national referral centre at La Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, Paris, France, between January 1980 and February 2016 were collected. All patients who met the World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) criteria for cardiac sarcoidosis [28, 29] and whose cardiac symptoms had appeared in 1980 or later were selected. Even in the presence of suggestive manifestations, cardiac biopsy is rarely realized because of its own risk and its poor diagnostic performance. In the present series, 5 out of 157 patients had had a cardiac biopsy with typical pathological features of sarcoidosis found in 3 of them. Of note, as for the present study we aimed to analyse the effect of steroid or immunosuppressant therapy, we did not include sarcoidosis patients who presented only the criteria “steroid ± immunosuppressant-responsive cardiomyopathy or heart block” [28, 29].

Any new cardiac (e.g. dyspnoea, syncope, heart failure, troubles of cardiac rhythm or conduction…) or non-cardiac symptoms attributed to sarcoidosis by the patient’s referral physician defined a relapse [5]. When appropriate, the relapse was confirmed by either radiological (echocardiography, cardiac MRI, cardiac FDG-PET scan, brain and/or spine MRI etc…) or pathological evidence. Ventricular extrasystoles were considered as a cardiac sarcoidosis manifestation when > 1000/24 hours. Hypertension was defined as either diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg or systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg. Whenever a biopsy was performed, a relapse was confirmed if the histopathological analysis revealed a well-defined non-caseating granuloma. Outcomes were assessed by the vital and relapse-free survivals. Patients with one or more-than-one relapse were considered as relapsers.

A switch or an adjustment of the dose of immunosuppressant was done within the following ranges: methotrexate 0.3–0.4 mg/kg/week; mycophenolic acid 2.0 to 3.0 g/day; azathioprine 50 to 150 mg/day. Intravenous cyclophosphamide was administered at the dose of 1g monthly, and infliximab at 5 mg/kg at 0, 2, 6 and then every 8 weeks.

The institutional review board of the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris approved this observational retrospective study, and informed consent was not required.

Patient and Public Involvement: it was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented with the median and interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables are presented with counts and proportions.

The date of the CS diagnosis was considered to be either the sarcoidosis diagnosis date (if the cardiac signs occurred concomitant with or prior to the sarcoidosis diagnosis), or the date of the first cardiac signs. Overall (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS), as defined previously [5], were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival functions were compared using the log rank test. Univariate analyses were performed in Cox regression models to identify baseline factors associated with OS and RFS. For RFS and cardiac-RFS analyses, multivariate models were selected by backward stepwise selection on p-values, using variables that were significant at a 5% level in univariate analysis. The association between recurrent relapse (any localization and cardiac) and sequences of CS treatments was examined in the subgroup of patients with at least one clinical Birnie’s criterion other than therapeutic response (see methods), using the Andersen-Gill Cox approach; this accounted for potential intra-patient correlation across observations. These recurrent events analyses were adjusted for New York Heart Association (NYHA) status (class 3–4 vs. 1–2), presence of cardiac rhythm disorders (yes vs. no), and presence of atrioventricular or ventricular conduction abnormalities (yes vs. no) during the follow-up.

All tests were two-sided, and a p-value below 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using R statistical platform software, version 3.2.2.

Patient and public involvement in research

We acknowledge that patient and public involvement is of importance. However, this appears not appropriate for the present papers.

Results

Characteristics of cardiac sarcoidosis patients

One hundred and seven patients [92 (59%) men, 77 (50%) Caucasians] met the new WASOG criteria for CS (median age 40 years, IQR 32–49) [29], with a median follow-up of 7 years (6 months– 32 years), 1 to 16 follow up visits, and a 60 months follow up in 67%. The cardiac signs occurred either prior to [n = 15, 10%], concomitant with [n = 54, 34%] or after [n = 88, 56%] the sarcoidosis diagnosis.

The main demographic data and extra-cardiac features are summarized in Table 1. Constitutional symptoms were observed in 43% of CS patients and 135/157 (86%) patients had two or more extra-cardiac sites, including mediastinal lymph nodes and/or lungs (89%), nervous system (42%), skin (31%), peripheral lymph nodes (30%), eyes (29%), and joints (24%). Elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme was noted in 86 (55%) patients.

Table 1. Main extra-cardiac features of 157 cardiac sarcoidosis patients.

| Variables | Number (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| General features | ||

| Age at cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosis (yrs) | 40 (32; 49) | |

| Male gender | 92/157 (59) | |

| Ethnic background | ||

| Caucasian | 77 (50) | |

| African / Caribbean | 43 (28) | |

| North African | 34 (22) | |

| Other | 3 (2) | |

| Active smoking habit | 20 (13) | |

| Extra-cardiac involvement | ||

| Number of extra-cardiac sites | ||

| 0 | 2 (1) | |

| 1 | 20 (13) | |

| 2 | 45 (29) | |

| 3 | 39 (25) | |

| > 3 | 51 (32) | |

| Abnormal chest X-ray | 130/146 (89%) | |

| Class 0 | 16 (11) | |

| Class I | 38 (26) | |

| Class II | 67 (46) | |

| Class III | 25 (17) | |

| General symptoms | 67 (43) | |

| Skin | 48 (31) | |

| Lymph node | 47 (30) | |

| Central nervous system | 45 (29) | |

| Eye | 45 (29) | |

| Joints | 37 (24) | |

| Liver or spleen | 36 (23) | |

| Exocrine gland | 27 (17) | |

| Ear, nose and throat | 8 (5) | |

| Kidney | 8 (5) | |

| Peripheral nervous system | 5 (3) | |

| Bones | 4 (3) | |

| Digestive tract | 3 (2) | |

The main clinical cardiac features are detailed in Table 2. Clinical manifestations of heart involvement were noted in all 157 (100%) patients, including ventricular block in 48/157 (31%), atrioventricular block in 27/157 (17%), ventricular arrhythmia in 27/157 (17%), left heart failure in 15/157 (10%), syncope in 10/157 (6%), and class 3 or 4 NYHA dyspnoea in 10/157 (6%). Of note, similar rates of NYHA class of dyspnoea were present whatever the results of pulmonary function tests, suggesting that most dyspnoea were related to cardiac dysfunction (S1 Table).

Table 2. Main clinical cardiac features of 157 cardiac sarcoidosis patients, according to the presence of cardiac relapse.

| Variables | Total | Cardiac relapse | No cardiac relapse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 157 | 63 | 94 |

| CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS, number (%) | |||

| Palpitation | 20 (13) | 8 (13) | 12 (13) |

| Syncope | 10 (6) | 4 (6) | 6 (6) |

| NYHA class dyspnoea | |||

| 1 | 119 (76) | 44 (70) | 75 (80) |

| 2 | 28 (18) | 15 (24) | 13 (14) |

| 3 | 7 (4) | 3 (5) | 4 (4) |

| 4 | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Left heart failure | 15 (10) | 10 (16) | 5 (5) |

| Right heart failure | 3 (2) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

| ELECTROCARDIOGRAM, number (%) | |||

| Any abnormality | 109 (69) | 46 (73) | 63 (67) |

| Atrial dysfonction | 55 (35) | 20 (32) | 35 (37) |

| Sinusal tachycardia | 49 (31)* | 17 (27) | 32 (34) |

| Fibrillation or flutter | 9 (6) | 3 (5) | 6 (6) |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 27 (17)* | 9 (14) | 18 (19) |

| Ventricular extrasystoles | 21 (13) | 8 (13) | 13 (14) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 13 (8) | 4 (6) | 9 (10) |

| Atrioventricular block | 27 (17)* | 16 (25) | 11 (12) |

| 1st degree | 15 (10) | 7 (11) | 8 (9) |

| 2nd degree | 9 (6) | 6 (10) | 3 (3) |

| 3rd degree | 6 (4) | 5 (8) | 1 (1) |

| Ventricular block | 38 (24)* | 13 (21) | 25 (27) |

| Right bundle branch | 33 (21) | 11 (17) | 22 (23) |

| Left bundle branch | 4 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Abnormal axis deviation | 35 (22) | 14 (22) | 21 (22) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 7 (4) | 2 (3) | 5 (5) |

| Q wave/ST-T changes | 5 (3) | 3 (5) | 2 (2) |

* 3 patients had both sinus tachycardia and atrial fibrillation/flutter; 7 patients had both ventricular extrasystoles and tachycardia; 3 patients had a 1st degree and a 2nd degree atrioventricular block; and 1 patient had left bundle branch block.

Table 3 summarizes the main cardiac imaging results. Echocardiography found abnormalities in 98/157 (62%) patients, including wall motion abnormalities in 20/157 (13%), thick interventricular septum in 18/156 (12%), and LVEF below forty percent in 15/152 (10%). Cardiac thallium scintigraphy showed localized or diffuse perfusion defects in a pattern consistent with CS in 107/133 (80%). Cardiac MRI was abnormal in 68/91 (75%) patients including early 12/88 (14%) or late 39/88 (44%) gadolinium enhancement, and low LVEF in 28/88 (32%). Cardiac FDG PET scan showed a patchy uptake in 12/37 (32%).

Table 3. Main imaging cardiac features of 157 cardiac sarcoidosis patients, according to the presence of cardiac relapse.

| Variables | Total | Cardiac relapse | No cardiac relapse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 157 | 63 | 94 |

| ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY, (n = 157), number (%) | |||

| Any abnormality | 98 (62) | 48 (76) | 50 (53) |

| Diffuse hypokinesia | 41 (26) | 23 (37) | 18 (19) |

| Localized hypokinesia | 40 (25) | 20 (32) | 20 (21) |

| Wall motion abnormalities | 20 (13) | 13 (21) | 7 (7) |

| Thick interventricular septum | 18 (12) | 6 (10) | 12 (13) |

| Abnormal pericardium | 18 (11) | 6 (10) | 12 (13) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | |||

| > 50% | 112 (74) | 41 (69) | 71 (76) |

| 50–40% | 25 (16) | 10 (17) | 15 (16) |

| < 40% | 15 (10) | 8 (14) | 7 (8) |

| CARDIAC SCINTIGRAPHY (n = 133), number (%) | |||

| Localized perfusion defects | 98 (74) | 40 (73) | 58 (74) |

| Diffuse perfusion defects | 9 (7) | 5 (9) | 4 (5) |

| CARDIAC MRI (n = 91), number (%) | |||

| Any abnormality | 68 (75) | 28 (85) | 40 (69) |

| Hypersignals (T1 mapping)* | 24 (28) | 11 (34) | 13 (24) |

| Early gadolinium enhancement † | 12 (14) | 6 (18) | 6 (11) |

| Delayed gadolinium enhancement † | 39 (44) | 19 (58) | 20 (36) |

| Localized hypokinesia† | 7 (8) | 3 (9) | 4 (7) |

| Low left ventricular ejection fraction† | 28 (32) | 11 (33) | 17 (31) |

| Abnormal pericardium** | 9 (11) | 1 (3) | 8 (15) |

| CARDIAC PET SCAN (n = 37), number (%) | |||

| Patchy uptake | 12 (32) | 2 (13) | 10 (45) |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET scan, positron emission tomography.

*n = 87

†: n = 88

**n = 85

Patients were given steroids either alone (n = 92) or in association with immunosuppressive drugs [n = 120, including intravenous cyclophosphamide (n = 79), methotrexate (n = 59), mycophenolic acid (n = 45), hydroxychloroquine (n = 29), infliximab (n = 14) and azathioprine (n = 8)] (S2 Table). The median (Q1-Q3) daily dose of steroids at entry and the end of follow-up was 53 mg (30–75) and 5 mg (3–10), respectively. Main steroids-related adverse effects were hypertension (24/157, 15%), diabetes (19/157, 12%), obesity (15/157, 11%), infections (13/157, 8%), osteoporosis (9/157, 6%), and tuberculosis (1/157, <1%). All patients also received conventional cardiac treatments, i.e. diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, anti-arrhythmic drugs, etc. Other cardiac treatments included a pace maker (7 patients), an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (2 patients), a pace maker plus an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (2 patients), a radio-ablation (3 patients), and a heart transplantation (2 patients).

Prognostic factors

Survival

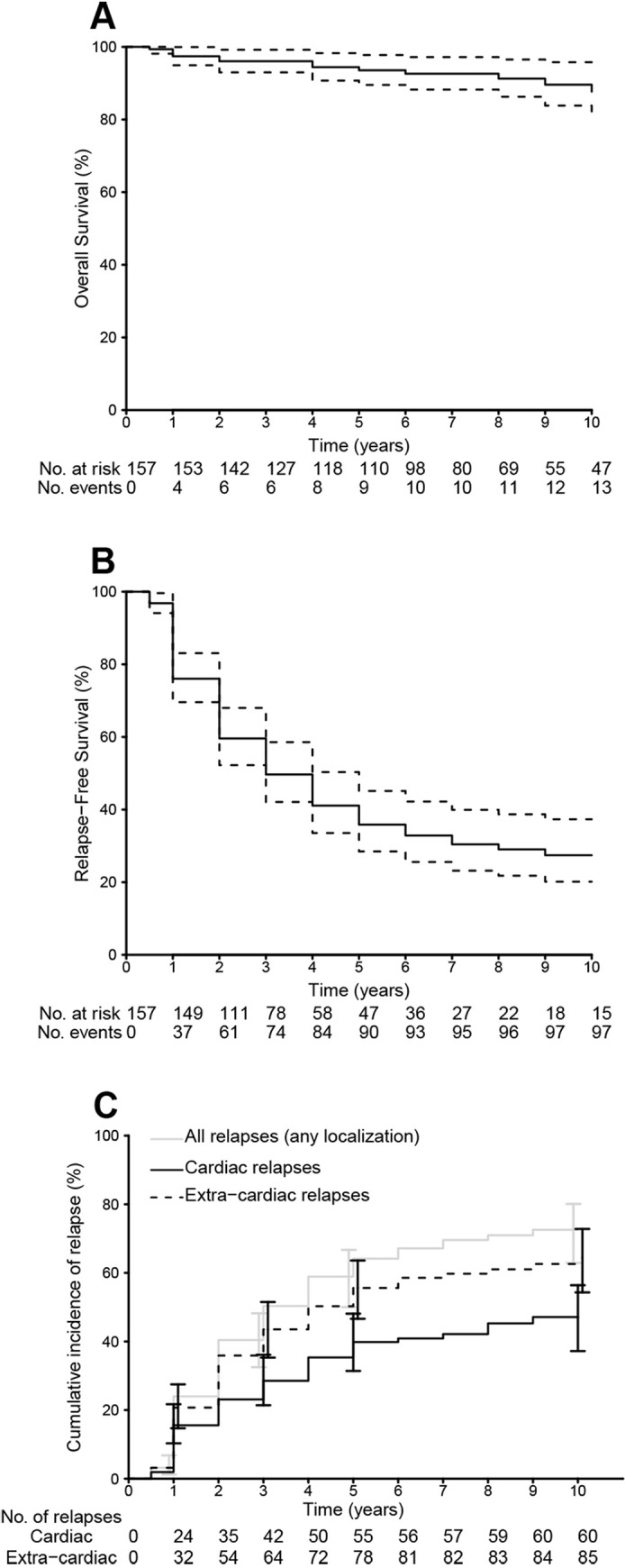

Thirteen out of 157 patients died during the follow-up. Overall survival rate at 5 and 10 years from CS diagnosis was 93.6% [95% CI, 89.5–97.8] and 89.6% [95% CI, 83.8–95.8], respectively (Fig 1A). Deaths were related to CS in four cases, i.e. two cases of refractory cardiac insufficiency, one post-heart transplant, and one unexplained sudden death. The other deaths were due to cerebral events (n = 4), severe asthma (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 1), suicide (n = 1), cardiac surgery not related to CS (n = 1) and unknown cause (n = 1). Univariate analysis found factors associated with fatal outcomes to be older age, LVEF below forty percent, hypertension, abnormal pulmonary function test, and the presence of delayed hypersignal enhancement on cardiac MRI (Table 4, S3 Table).

Fig 1.

Overall survival of cardiac sarcoidosis patients (Kaplan-Meier) (panel A). Relapse-free survival for all relapses (panel B). Cumulative incidences of cardiac, extra-cardiac, and all relapses (panel C). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time lapsed from the date of CS diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time lapsed from the date of CS diagnosis to the date of first sarcoidosis relapse, death or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Both cardiac and non-cardiac relapses were included for RFS analyses.

Table 4. Main features associated with overall and relapse-free survivals (all relapses), and cardiac relapses in cardiac sarcoidosis patients (univariate analysis).

| Overall survival | Relapse-free survival | Cardiac relapses† | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Deaths /patients | HR (95% CI) | P | Relapses/patients | HR (95% CI) | P | Relapses/patients | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| General features | ||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis (HR per 10 years) | - | 1.69 (1.13–2.52) | 0.010 | - | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.18 | - | 1.19 (0.99–1.44) | 0.062 | |

| Male gender | 5/92 | 0.47 (0.15–1.45) | 0.19 | 57/92 | 0.92 (0.62–1.36) | 0.67 | 36/92 | 0.95 (0.57–1.57) | 0.83 | |

| Ethnic Background | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 8/78 | 1 | 45/78 | 1 | 52/102 | 1 | ||||

| African/Carib | 4/43 | 0.81 (0.24–2.68) | 0.72 | 36/43 | 1.78 (1.14–2.78) | 0.011 | 22/43 | 1.47 (0.84–2.59) | 0.18 | |

| North African | 1/34 | 0.26 (0.032–2.08) | 0.20 | 20/34 | 1.17 (0.69–1.99) | 0.55 | 12/34 | 1.01 (0.51–1.97) | 0.99 | |

| Smoking | 0/20 | - | 0.19‡ | 15/20 | 2.02 (1.16–3.51) | 0.013 | 8/20 | 1.23 (0.58–2.56) | 0.59 | |

| Hypertension | 2/8 | 4.79 (1.06–21.7) | 0.042 | 5/8 | 2.32 (0.93–5.77) | 0.071 | 4/8 | 2.33 (0.84–6.47) | 0.10 | |

| Extra-cardiac involvement | ||||||||||

| > 2 sites involved | 6/90 | 0.57 (0.19–1.70) | 0.31 | 57/90 | 0.89 (0.60–1.33) | 0.57 | 32/90 | 0.66 (0.40–1.37) | 0.44 | |

| General symptoms | 5/67 | 0.96 (0.31–2.94) | 0.94 | 42/67 | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) | 0.96 | 23/67 | 0.82 (0.49–1.37) | 0.44 | |

| CNS | 3/45 | 0.70 (0.19–2.56) | 0.59 | 31/45 | 1.43 (0.93–2.18) | 0.10 | 20/45 | 1.40 (0.82–2.38) | 0.22 | |

| Lung | 13/130 | 0.17‡ | 85/130 | 0.97 (0.53–1.78) | 0.93 | 55/130 | 1.65 (0.66–4.14) | 0.29 | ||

| Abnormal pulmonary test | 8/50 | 3.27 (1.07–10.0) | 0.038 | 34/50 | 1.20 (0.79–1.82) | 0.39 | 22/50 | 1.26 (0.75–2.13) | 0.38 | |

| Eye | 1/45 | 0.21 (0.027–1.61) | 0.13 | 29/45 | 1.07 (0.69–1.65) | 0.76 | 13/45 | 0.63 (0.34–1.16) | 0.14 | |

| Lymph nodes | 1/47 | 0.17 (0.022–1.30) | 0.088 | 29/47 | 0.91 (0.59–1.41) | 0.68 | 16/47 | 0.71 (0.40–1.25) | 0.24 | |

| Skin | 6/48 | 1.95 (0.66–5.81) | 0.23 | 26/48 | 0.61 (0.39–0.95) | 0.029 | 13/48 | 0.47 (0.25–0.87) | 0.016 | |

| Liver or spleen | 3/36 | 0.88 (0.24–3.22) | 0.85 | 28/36 | 1.41 (0.91–2.18) | 0.13 | 17/36 | 1.14 (0.65–1.99) | 0.64 | |

| Joints | 1/37 | 0.25 (0.033–1.95) | 0.19 | 21/37 | 0.68 (0.42–1.10) | 0.12 | 11/37 | 0.58 (0.30–1.11) | 0.10 | |

| Exocrine glands | 2/27 | 0.84 (0.19–3.80) | 0.84 | 18/27 | 0.86 (0.51–1.43) | 0.56 | 9/27 | 0.69 (0.34–1.39) | 0.30 | |

| ENT | 0/8 | - | 0.34‡ | 7/8 | 1.64 (0.76–3.55) | 0.21 | 2/8 | 0.47 (0.12–1.94) | 0.30 | |

| Kidney | 0/8 | - | 0.37‡ | 7/8 | 4.42 (2.01–9.69) | 0.0002 | 6/8 | 4.10 (1.76–9.58) | 0.001 | |

| Cardiac involvement | ||||||||||

| NYHA class | 2/10 | 2.80 (0.62–12.6) | 0.18 | 6/10 | 0.93 (0.40–2.12) | 0.86 | 4/10 | 1.11 (0.40–3.05) | 0.84 | |

| Left heart failure | 3/15 | 2.45 (0.67–8.99) | 0.18 | 11/15 | 1.66 (0.53–2.03) | 0.81 | 10/15 | 2.01 (1.02–3.95) | 0.044 | |

| Right heart failure | 1/3 | 3.29 (0.42–25.9) | 0.26 | 3/3 | 1.66 (0.53–5.26) | 0.39 | 3/3 | 3.29 (1.03–10.5) | 0.045 | |

| AV block | 5/27 | 3.62 (1.18–11.1) | 0.025 | 19/27 | 1.21 (0.72–2.01) | 0.47 | 16/27 | 2.12 (1.17–3.82) | 0.013 | |

| High degree AV block | 4/15 | 5.56 (1.70–18.2) | 0.005 | 13/15 | 1.80 (0.98–3.30) | 0.058 | 11/15 | 2.88 (1.45–5.72) | 0.003 | |

| Left bundle branch block | 3/10 | 5.13 (1.41–18.7) | 0.013 | 7/10 | 1.04 (0.48–2.24) | 0.92 | 5/10 | 1.37 (0.55–3.41) | 0.50 | |

| LVEF < 40% | 3/10 | 4.88 (1.26–18.9) | 0.022 | 9/15 | 0.87 (0.83–1.73) | 0.68 | 8/15 | 1.60 (0.75–3.42) | 0.22 | |

| Septal hypertrophy | 1/18 | 0.59 (0.08–4.51) | 0.61 | 12/18 | 1.00 (0.54–1.83) | 0.99 | 6/18 | 0.74 (0.32–1.71) | 0.48 | |

| Wall motion abnormalities | 4/20 | 2.51 (0.77–8.20) | 0.13 | 16/20 | 1.18 (0.69–2.01) | 0.54 | 13/20 | 1.91 (1.03–3.52) | 0.039 | |

| Delayed MRI hypersignal | 5/39 | 2.26 (0.25–20.4) | 0.003 | 26/39 | 1.53 (0.92–2.57) | 0.10 | 19/39 | 1.86 (0.98–3.52) | 0.056 | |

Carib, Caribbean; CNS, central nervous system; ENT, ear, nose, throat; NYHA, New York Heart Association; AV, atrio-ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ENT, Ear, nose and throat.

‡P-value of Log-Rank test; Estimation of hazards ratio using a Cox regression model was not performed due to the absence of event in one subgroup of interest.

Relapses

A hundred and one patients had at least one sarcoidosis-related event, i.e. 63 cardiac relapses and 88 non-cardiac relapses. No death without prior relapse was noted. After 10 years of follow up, the overall RFS rate (cardiac and non-cardiac) was 27.4% (95% CI, 20.2–37.3) (Fig 1B). The cardiac RFS rate was 52.9% (95% CI, 44.1–63.4). Cumulative incidences of cardiac and non-cardiac relapses at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 6% (95% CI 10–21) and 24% (95% CI 17–30), 32% (21–35) and 50% (43–58), 40% (31–48) and 64% (55–71), and 47% (37–56) and 73% (63–80), respectively (Fig 1C).

Univariate analysis showed factors associated with cardiac relapse to be baseline kidney involvement, high degree atrioventricular block, and the presence of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI (Table 4, S3 Table). The presence of skin involvement was associated with a lower risk of cardiac relapse.

In multivariate analysis, factors associated with cardiac relapse were baseline kidney involvement, left heart failure and wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography, whereas skin involvement was inversely associated.

The impact of immunosuppressive treatments on the relapse risk over a treatment course (any localization or cardiac) is detailed in Table 5. Only the administration of intravenous cyclophosphamide was associated with a significant decrease of cardiac relapse risk (HR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03–0.75, p = 0.020) compared with the absence of treatment. The HR was 0.37 (0.13–1.08, p = 0.069) for the risk of recurrent relapse, including all localization. The administration of glucocorticoids alone, methotrexate or mycophenolic acid were all associated with a non-statistically significant decrease of cardiac relapse rate. Detailed description of treatment sequences included in this analysis is available in S4 Table.

Table 5. Hazards ratios for relapses (any localization, left; cardiac relapses, right) in cardiac sarcoidosis patients, according to immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory treatments.

| Treatment | All relapses /therapeutic sequences | HR (95%CI)‡ | P | Cardiac relapses /therapeutic sequences | HR (95%CI)‡ | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10/13 | 1 | - | 8/13 | 1 | - |

| Glucocorticoid alone | 17/77 | 0.51 (0.20–1.31) | 0.16 | 11/77 | 0.48 (0.18–1.31) | 0.15 |

| Methotrexate | 24/74 | 1.28 (0.43–3.75) | 0.66 | 9/74 | 0.62 (0.17–2.19) | 0.46 |

| Mycophenolic acid | 9/54 | 0.60 (0.21–1.69) | 0.33 | 5/54 | 0.47 (0.15–1.47) | 0.19 |

| Intravenous cyclophosphamide | 6/48 | 0.37 (0.13–1.08) | 0.069 | 2/48 | 0.16 (0.033–0.75) | 0.020 |

| Other* | 9/26 | 0.76 (0.22–2.61) | 0.67 | 5/26 | 0.48 (0.16–1.41) | 0.18 |

*Hydroxychloroquine alone (n = 16), infliximab (n = 4), azathioprine alone (n = 3), other immunosuppressant (n = 3)

†Analysis was performed including sequences of treatments between follow-up visits, excluding patients with a clinical therapeutic response as part of their diagnosis Birnie criteria and excluding periods of disease persistence.

‡ Analysis was adjusted on NYHA status (class 3–4 vs. 1–2), presence of cardiac rhythm disorders (yes vs. no), and presence of atrioventricular or ventricular conduction abnormalities (yes vs. no) during follow-up (time-dependent).

Discussion

In the present study, one of the largest published cohort of patients that has met the new criteria for CS and has had a long follow up, we found that: 1) the 10-year mortality rate was low and associated with older age at CS diagnosis, hypertension, abnormal pulmonary function test, low LVEF, and areas of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI; 2) the 10-year relapse-rate was high and associated to baseline kidney involvement, left heart failure and the presence wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography; and 3) of the immunosuppressant used, only intravenous cyclophosphamide was associated with a significant decrease in cardiac relapse rates.

Although recent data are reassuring [6, 11, 24], patients with CS have a poorer prognosis than patients without cardiac involvement. The extent of left ventricle dysfunction has been reported as a major predictor of survival [18, 19]. In the study by Chiu et al. at 10 years, all patients with normal ejection fraction were alive whereas patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction had a survival rate of 19% [19]. Some studies found that patients with clinically silent CS have a benign course [25, 30–32]; however contrasting results have been reported [33–36]. In the present series, most deaths were not due to cardiac sarcoidosis, suggesting that CS might be also a marker of an aggressive sarcoidosis. Death was associated with areas of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI, a sign of myocardium fibrosis/scar reported as a pejorative factor [11, 21–23, 25, 30, 37–39]. Interestingly, repeat FDG PET scan may help to determine the extent of disease activity and to assess the cardiac response to therapy [40–42]. Promising technologies using cardiac FDG PET scan plus MRI might enable concurrent imaging of the two stages of the disease, i.e. inflammation and fibrosis [43].

For patients with extra-pulmonary i.e. cardiac, ocular, neurological, or renal sarcoidosis or hypercalcemia, treatment is recommended [44]. Non-randomized studies have suggested that steroids should be proposed as soon as possible, with good efficacy on ventricular arrhythmia, acute cardiac insufficiency and atrioventricular block [6, 24, 27, 45]. No prognostic difference was found in patients treated with high or moderate doses of prednisone [46]. Immunosuppressant, often used in refractory cases and/or if steroid side effects, included methotrexate [6, 22, 24, 25], azathioprine [22, 47], cyclophosphamide [6, 48], mycophenolate mofetil [22, 24] and more recently infliximab [49–53]. In the present study, only intravenous cyclophosphamide was associated with a significant decrease in cardiac relapse rates. Other immunosuppressive drugs used were also associated with a lower cardiac relapse risk (i.e. glucocorticoid alone, methotrexate or mycophenolic acid). Probably due to the lack of sufficient power and/or insufficient efficacy and/or use as second-line therapies in refractory CS, the latter results were not statistically significant. In the present series, the number of patients who received infliximab was too small to draw firm conclusions [49–53]. Of note, analyses on treatments should be interpreted with caution as treatments were not randomised (possible confounding factors), and sample sizes of some treatment were small (under power). Despite a widespread use of steroids and immunosuppressant drugs, the adverse effect rate remained low. This is probably related to the low dose of steroids patients received at the end of follow up. This highlights a benefit/risk balance in favour of long-term immunosuppression in CS patients, particularly if patients show factors predictive of poor outcome or cardiac relapse.

Limitations

Due to the rarity of the disease, we analysed retrospective data. A referral centre bias may explain some of the characteristics of our cohort (multi-systemic severe forms of sarcoidosis, rarity of atrio-ventricular block). The clinical variety of CS required the use of complex statistical models. A multivariate analysis was not feasible for overall survival due to the small number of events. Due to the long enrollment period, we cannot exclude possible implications of change in backward cardiovascular therapies or diagnostic tools on outcomes. Only a part of the patients did cardiac MRI and cardiac FDG-PET scan, both fundamental in relapse and prognostic evaluation. Also, as mentioned above, immunosuppressive treatments were not randomised.

Conclusion

In patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, more frequent relapses were found to be associated with baseline kidney involvement, left heart failure and the presence of wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography. Mortality rate was low and associated to older age, arterial hypertension, abnormal pulmonary function tests, low LVEF and the presence of areas of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI. Immunosuppressive therapy with intravenous cyclophosphamide is associated with lower relapse rates and might be especially of interest when predictive factors of poor outcome or relapses are present. Such results should be confirmed in randomized controlled trials.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Ungprasert P, Carmona EM, Utz JP, Ryu JH, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Epidemiology of Sarcoidosis 1946–2013: A Population-Based Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(2):183–188. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillerdal G, Nöu E, Osterman K, Schmekel B. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology and prognosis. A 15-year European study. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:29–32. 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014;383:1155–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RS. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016. July 26;68(4):411–21. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joubert B, Chapelon-Abric C, Biard L, Saadoun D, Demeret S, Dormont D, et al. Association of Prognostic Factors and Immunosuppressive Treatment With Long-term Outcomes in Neurosarcoidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017. November 1;74(11):1336–1344. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapelon-Abric C, Sene D, Saadoun D, Cluzel P, Vignaux O, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: Diagnosis, therapeutic management and prognostic factors. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017. Aug-Sep;110(8–9):456–465. 10.1016/j.acvd.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwai K, Tachibana T, Takemura T, Matsui Y, Kitaichi M, Kawabata Y. Pathological studies on sarcoidosis autopsy. Epidemiological features of 320 cases in Japan. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993;43:372–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1993.tb01148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry A, Vuitch F. Causes of death in patients with sarcoidosis. A morphologic study of 38 autopsies with clinicopathologic correlations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995;119:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton KM, Ganigara M, Corte P, Celermajer DS, McGuire MA, Torzillo PJ, et al. The Utility of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Heart Lung Circ. 2017. November;26(11):1191–1199. 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedema JP, van Geuns RJ, Ainslie G, Ector J, Heidbuchel H, Crijns HJGM. Right ventricular involvement in cardiac sarcoidosis demonstrated with cardiac magnetic resonance. ESC Heart Fail. 2017. November;4(4):535–544 10.1002/ehf2.12166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandolin R, Lehtonen J, Kupari M. Cardiac sarcoidosis and giant cell myocarditis as causes of atrioventricular block in young and middle-aged adults. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4: 303–9. 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nery PB, Beanlands RS, Nair GM, Green M, Yang J, McArdle BA, et al. Atrioventricular block as the initial manifestation of cardiac sarcoidosis in middle-aged adults. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:875–81. 10.1111/jce.12401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tung R, Bauer B, Schelbert H, Lynch JP, Auerbach M, Gupta P, et al. Incidence of abnormal positron emission tomography in patients with unexplained cardiomyopathy and ventricular arrhythmias: the potential role of occult inflammation in arrhythmogenesis. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:2488–98. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nery PB, Mc Ardle BA, Redpath CJ, Redpath CJ, Leung E, Lemery R, et al. Prevalence of cardiac sarcoidosis in patients presenting with monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014;367: 364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segura AM, Radovancevic R, Demirozu ZT, Frazier OH, Buja LM. Granulomatous myocarditis in severe heart failure patients undergoing implantation of a left ventricular assist device. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2014. Jan-Feb;23(1):17–20. 10.1016/j.carpath.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts WC, Chung MS, Ko JM, Capehart JE, Hall SA. Morphologic features of cardiac sarcoidosis in native hearts of patients having cardiac transplantation. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:706–12. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philips B, Madhavan S, James CA, te Riele AS, Murray B, Tichnell C, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and cardiac sarcoidosis: distinguishing features when the diagnosis is unclear. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7: 230–6. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadek MM, Yung D, Birnie DH, Beanlands RS, Nery PB. Corticosteroid therapy for cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1034–41. 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu CZ, Nakatani S, Zhang G, Tachibana T, Ohmori F, Yamagishi M, et al. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling by long-term corticosteroid therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:143–6. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandolin R, Lehtonen J, Airaksinen J, Vihinen T, Miettinen H, Ylitalo K, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome over 25 years in a nationwide study. Circulation. 2015. February 17;131(7):624–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel N, Kalra R, Doshi R, Arora H, Bajaj NS, Arora G, et al. Hospitalization Rates, Prevalence of Cardiovascular Manifestations, and Outcomes Associated With Sarcoidosis in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018. January 22;7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordenswan HK, Lehtonen J, Ekström K, Kandolin R, Simonen P, Mäyränpää M, et al. Outcome of cardiac sarcoidosis presenting with high-grade atrioventricular block. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018; 11e006145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S, Nakano T, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiacsarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol. 2001. November 1;88(9):1006–10. 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01978-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Lower EE, Li HP, Costea A, Attari M, Baughman RP. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: The Impact of Age and Implanted Devices on Survival. Chest. 2017. January;151(1):139–148. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagai S, Yokomatsu T, Tanizawa K, Ikezoe K, Handa T, Ito Y, et al. Treatment with methotrexate and low-dose orticosteroids in sarcoidosis patients with cardiac lesions. Intern Med 2014;53:2761 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okabe T, Yakushiji T, Hiroe M, Oyama Y, Igawa W, Ono M, et al. Steroid pulse therapy was effective for cardiac sarcoidosis with ventricular tachycardia and systolic dysfunction. ESC heart Fail 2016; 3 (4): 288–292. 10.1002/ehf2.12095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padala SK, Peaslee S, Sidhu MS, Steckman DA, Judson MA. Impact of early initiation of corticosteroid therapy on cardiac function and rhythm in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J cardio 2017. 15; 227: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CS, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014. July;11(7):1305–23. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birnie DH, Kandolin R, Nery PB, Kupari M. Cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Eur Heart J. 2017. September 14;38(35):2663–2670. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta D, Lubitz SA, Frankel Z, Wisnivesky JP, Einstein AJ, Goldman M, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008. June;133(6):1426–1435. 10.1378/chest.07-2784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, van Geuns RJ, Cheriex EC, Gorgels AP, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis assessed at two university medical centers in the Netherlands. Chest 2005; 128:30–5. 10.1378/chest.128.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vignaux O, Dhote R, Duboc D, Blanche P, Dusser D, Weber S, et al. Detection of myocardial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis applying T2-weighted, contrast enhanced, and cine magnetic resonance imaging: initial results of a prospective study. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002;26:762–7. 10.1097/00004728-200209000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel MR, Cawley PJ, Heitner JF, Klem I, Parker MA, Jaroudi WA, et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation 2009;120:1969–77. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greulich S, Deluigi CC, Gloekler S, Wahl A, Zürn C, Kramer U, et al. CMR imaging predicts death and other adverse events in suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging 2013;6:501–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murtagh G, Laffin LJ, Beshai JF, Maffessanti F, Bonham CA, Patel AV, et al. Prognosis of myocardial damage in sarcoidosis patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: risk stratification using cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9: e003738 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Huie TJ, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, Sprunger D, et al. Sarcoidosis-related Mortality in the United States from 1988 to 2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(11):1524–1530. 10.1164/rccm.201010-1679OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ise T, Hasegawa T, Morita Y, Yamada N, Funada A, Takahama H, et al. Extensive late gadolinium enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts adverse outcomes and lack of improvement in LV function after steroid therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart. 2014. August;100(15):1165–72. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takaya Y, Kusano KF, Nakamura K, Ito H. Outcomes in patients with high-degree atrioventricular block as the initial manifestation of cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2015. February 15;115(4):505–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawford TC. Multimodality imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis: predicting treatment response. Heart Rhythm. 2015. December;12(12):2486–7. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pl Lee, Cheng G, Alavi A. The role of serial FDG PET for assessing therapeutic response in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl cardiol 2017; 24 (1): 19–28. 10.1007/s12350-016-0682-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shelke AB, Aurangabadkar HU, Bradfield JS, Ali Z, Kular KS, Narasimhan C. Serial FDG-PET scans help to identify steroid resistance in cardiac sarcoidosis Int J Cardiol 2017; 1; 228: 717–722. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohira H, Ardle BM, deKemp RA, Nery P, Juneau D, Renaud JM, et al. Inter- and intraobserver agreement of 18F-FDG PET/CT image interpretation in patients referred for assessment of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2017. August;58(8):1324–1329. 10.2967/jnumed.116.187203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White JA, Rajchl M, Butler J, Thompson RT, Prato FS, Wisenberg G. Active cardiac sarcoidosis: first clinical experience of simultaneous positron emission tomography—magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of cardiac disease. Circulation. 2013. June 4;127(22):e639–41. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grutters JC, van den Bosch JM. Corticosteroid treatment in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 2006;28: 627–36. 10.1183/09031936.06.00105805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yodogawa K, Seino Y, Ohara T, Takayama H, Katoh T, Mizuno K. Effect of corticosteroid therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2011; 16 (2): 140–147. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2011.00418.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, Morimoto S, Hiramitsu S, Nakano T, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:1006–10. 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01978-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller-Quernheim J, Kienast K, Held M, Pfeifer S, Costabel U. Treatment of chronic sarcoidosis with an azathioprine/ prednisolone regimen. Eur Respir J 1999;14: 1117–22. 10.1183/09031936.99.14511179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demeter SL. Myocardial sarcoidosis unresponsive to steroids. Treatment with cyclophosphamide. Chest 1988;94:202–3. 10.1378/chest.94.1.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, Flavin S, Lo KH, Kavuru MS, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J 2008; 31:1189–96. 10.1183/09031936.00051907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puyraimond-Zemmour D, Chapelon-Abric C, Saadoun D, Bouvry D, Ruivard M, André M, et al. Efficacy and Tolerance of TNF Alpha Inhibitor (TNFI) Treatment in Cardiac Sarcoidosis (CS). 81st Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. San Diego. Abstract number 2904, November 2017.

- 51.Jamilloux Y, Cohen-Aubart F, Chapelon-Abric C, Maucort-Boulch D, Marquet A, Pérard L, et al. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in refractory sarcoidosis: A multicenter study of 132 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017. October;47(2):288–294. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapelon-Abric C, Saadoun D, Biard L, Sene D, Resche-Rigon M, Hervier B, et al. Long-term outcome of infliximab in severe chronic and refractory systemic sarcoidosis: a report of 16 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015. Jul-Aug;33(4):509–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uthman I, Touma Z, Khoury M. Cardiac sarcoidosis responding to monotherapy with infliximab. Clin Rheumatol. 2007. November;26(11):2001–3. 10.1007/s10067-007-0614-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.